|

GCD Domain

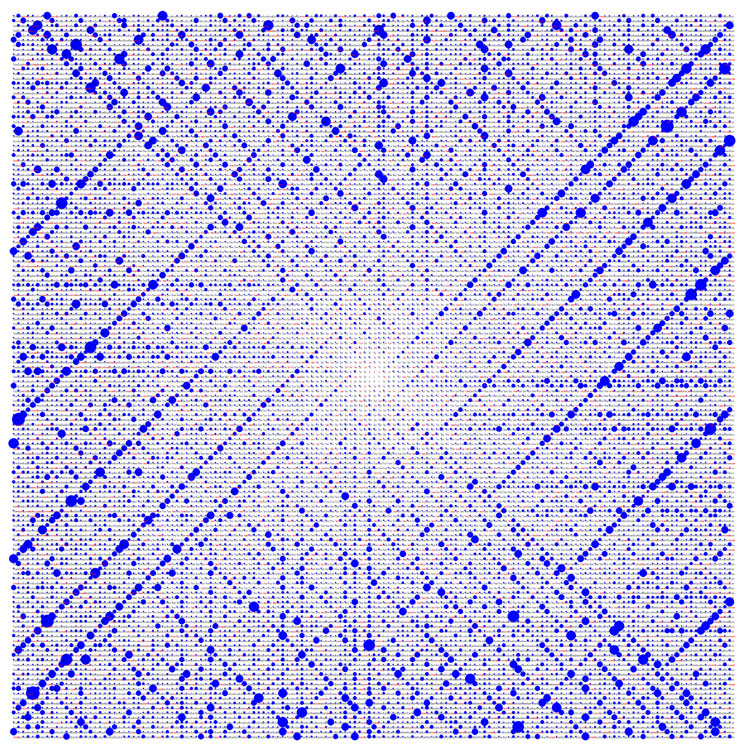

In mathematics, a GCD domain (sometimes called just domain) is an integral domain ''R'' with the property that any two elements have a greatest common divisor (GCD); i.e., there is a unique minimal principal ideal containing the ideal generated by two given elements. Equivalently, any two elements of ''R'' have a least common multiple (LCM). A GCD domain generalizes a unique factorization domain (UFD) to a non-Noetherian setting in the following sense: an integral domain is a UFD if and only if it is a GCD domain satisfying the ascending chain condition on principal ideals (and in particular if it is Noetherian). GCD domains appear in the following chain of class inclusions: Properties Every irreducible element of a GCD domain is prime. A GCD domain is integrally closed, and every nonzero element is primal. In other words, every GCD domain is a Schreier domain. For every pair of elements ''x'', ''y'' of a GCD domain ''R'', a GCD ''d'' of ''x'' and ''y'' and an LCM ' ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many areas of mathematics, which include number theory (the study of numbers), algebra (the study of formulas and related structures), geometry (the study of shapes and spaces that contain them), Mathematical analysis, analysis (the study of continuous changes), and set theory (presently used as a foundation for all mathematics). Mathematics involves the description and manipulation of mathematical object, abstract objects that consist of either abstraction (mathematics), abstractions from nature orin modern mathematicspurely abstract entities that are stipulated to have certain properties, called axioms. Mathematics uses pure reason to proof (mathematics), prove properties of objects, a ''proof'' consisting of a succession of applications of in ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Equivalence Relation

In mathematics, an equivalence relation is a binary relation that is reflexive, symmetric, and transitive. The equipollence relation between line segments in geometry is a common example of an equivalence relation. A simpler example is equality. Any number a is equal to itself (reflexive). If a = b, then b = a (symmetric). If a = b and b = c, then a = c (transitive). Each equivalence relation provides a partition of the underlying set into disjoint equivalence classes. Two elements of the given set are equivalent to each other if and only if they belong to the same equivalence class. Notation Various notations are used in the literature to denote that two elements a and b of a set are equivalent with respect to an equivalence relation R; the most common are "a \sim b" and "", which are used when R is implicit, and variations of "a \sim_R b", "", or "" to specify R explicitly. Non-equivalence may be written "" or "a \not\equiv b". Definitions A binary relation \,\si ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Semigroup

In mathematics, a semigroup is an algebraic structure consisting of a set together with an associative internal binary operation on it. The binary operation of a semigroup is most often denoted multiplicatively (just notation, not necessarily the elementary arithmetic multiplication): , or simply ''xy'', denotes the result of applying the semigroup operation to the ordered pair . Associativity is formally expressed as that for all ''x'', ''y'' and ''z'' in the semigroup. Semigroups may be considered a special case of magmas, where the operation is associative, or as a generalization of groups, without requiring the existence of an identity element or inverses. As in the case of groups or magmas, the semigroup operation need not be commutative, so is not necessarily equal to ; a well-known example of an operation that is associative but non-commutative is matrix multiplication. If the semigroup operation is commutative, then the semigroup is called a ''commutative semigroup' ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Cancellative Semigroup

In mathematics, a cancellative semigroup (also called a cancellation semigroup) is a semigroup having the cancellation property. In intuitive terms, the cancellation property asserts that from an equality of the form ''a''·''b'' = ''a''·''c'', where · is a binary operation, one can cancel the element ''a'' and deduce the equality ''b'' = ''c''. In this case the element being cancelled out is appearing as the left factors of ''a''·''b'' and ''a''·''c'' and hence it is a case of the left cancellation property. The right cancellation property can be defined analogously. Prototypical examples of cancellative semigroups are the positive integers under addition or multiplication. Cancellative semigroups are considered to be very close to being groups because cancellability is one of the necessary conditions for a semigroup to be embeddable in a group. Moreover, every finite cancellative semigroup is a group. One of the main problems associated with the study of cancellative ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Torsion-free Group

In mathematics, specifically in ring theory, a torsion element is an element of a module that yields zero when multiplied by some non-zero-divisor of the ring. The torsion submodule of a module is the submodule formed by the torsion elements (in cases when this is indeed a submodule, such as when the ring is commutative). A torsion module is a module consisting entirely of torsion elements. A module is torsion-free if its only torsion element is the zero element. This terminology is more commonly used for modules over a domain, that is, when the regular elements of the ring are all its nonzero elements. This terminology applies to abelian groups (with "module" and "submodule" replaced by "group" and "subgroup"). This is just a special case of the more general situation, because abelian groups are modules over the ring of integers. (In fact, this is the origin of the terminology, which was introduced for abelian groups before being generalized to modules.) In the case of gro ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Monoid Ring

In abstract algebra, a monoid ring is a ring constructed from a ring and a monoid, just as a group ring is constructed from a ring and a group. Definition Let ''R'' be a ring and let ''G'' be a monoid. The monoid ring or monoid algebra of ''G'' over ''R'', denoted ''R'' 'G''or ''RG'', is the set of formal sums \sum_ r_g g, where r_g \in R for each g \in G and ''r''''g'' = 0 for all but finitely many ''g'', equipped with coefficient-wise addition, and the multiplication in which the elements of ''R'' commute with the elements of ''G''. More formally, ''R'' 'G''is the free ''R''-module on the set ''G'', endowed with ''R''-linear multiplication defined on the base elements by ''g·h'' := ''gh'', where the left-hand side is understood as the multiplication in ''R'' 'G''and the right-hand side is understood in ''G''. Alternatively, one can identify the element g \in R with the function ''eg'' that maps ''g'' to 1 and every other element of ''G'' to 0. This way, ''R'' 'G''is identifi ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Commutative Ring

In mathematics, a commutative ring is a Ring (mathematics), ring in which the multiplication operation is commutative. The study of commutative rings is called commutative algebra. Complementarily, noncommutative algebra is the study of ring properties that are not specific to commutative rings. This distinction results from the high number of fundamental properties of commutative rings that do not extend to noncommutative rings. Commutative rings appear in the following chain of subclass (set theory), class inclusions: Definition and first examples Definition A ''ring'' is a Set (mathematics), set R equipped with two binary operations, i.e. operations combining any two elements of the ring to a third. They are called ''addition'' and ''multiplication'' and commonly denoted by "+" and "\cdot"; e.g. a+b and a \cdot b. To form a ring these two operations have to satisfy a number of properties: the ring has to be an abelian group under addition as well as a monoid under m ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Prüfer Domain

In mathematics, a Prüfer domain is a type of commutative ring that generalizes Dedekind domains in a non-Noetherian context. These rings possess the nice ideal and module theoretic properties of Dedekind domains, but usually only for finitely generated modules. Prüfer domains are named after the German mathematician Heinz Prüfer. Examples The ring of entire functions on the open complex plane C form a Prüfer domain. The ring of integer valued polynomials with rational coefficients is a Prüfer domain, although the ring \mathbb /math> of integer polynomials is not . While every number ring is a Dedekind domain, their union, the ring of algebraic integers, is a Prüfer domain. Just as a Dedekind domain is locally a discrete valuation ring, a Prüfer domain is locally a valuation ring, so that Prüfer domains act as non-noetherian analogues of Dedekind domains. Indeed, a domain that is the direct limit of subrings that are Prüfer domains is a Prüfer domain . Ma ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Entire Function

In complex analysis, an entire function, also called an integral function, is a complex-valued function that is holomorphic on the whole complex plane. Typical examples of entire functions are polynomials and the exponential function, and any finite sums, products and compositions of these, such as the trigonometric functions sine and cosine and their hyperbolic counterparts sinh and cosh, as well as derivatives and integrals of entire functions such as the error function. If an entire function f(z) has a root at w, then f(z)/(z-w), taking the limit value at w, is an entire function. On the other hand, the natural logarithm, the reciprocal function, and the square root are all not entire functions, nor can they be continued analytically to an entire function. A transcendental entire function is an entire function that is not a polynomial. Just as meromorphic functions can be viewed as a generalization of rational fractions, entire functions can be viewed as a ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Principal Ideal Domain

In mathematics, a principal ideal domain, or PID, is an integral domain (that is, a non-zero commutative ring without nonzero zero divisors) in which every ideal is principal (that is, is formed by the multiples of a single element). Some authors such as Bourbaki refer to PIDs as principal rings. Principal ideal domains are mathematical objects that behave like the integers, with respect to divisibility: any element of a PID has a unique factorization into prime elements (so an analogue of the fundamental theorem of arithmetic holds); any two elements of a PID have a greatest common divisor (although it may not be possible to find it using the Euclidean algorithm). If and are elements of a PID without common divisors, then every element of the PID can be written in the form , etc. Principal ideal domains are Noetherian, they are integrally closed, they are unique factorization domains and Dedekind domains. All Euclidean domains and all fields are principal ideal domain ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Bézout Domain

In mathematics, a Bézout domain is an integral domain in which the sum of two principal ideals is also a principal ideal. This means that Bézout's identity holds for every pair of elements, and that every finitely generated ideal is principal. Bézout domains are a form of Prüfer domain. Any principal ideal domain (PID) is a Bézout domain, but a Bézout domain need not be a Noetherian ring, so it could have non-finitely generated ideals; if so, it is not a unique factorization domain (UFD), but is still a GCD domain. The theory of Bézout domains retains many of the properties of PIDs, without requiring the Noetherian property. Bézout domains are named after the French mathematician Étienne Bézout. Examples * All PIDs are Bézout domains. * Examples of Bézout domains that are not PIDs include the ring of entire functions (functions holomorphic on the whole complex plane) and the ring of all algebraic integers. In case of entire functions, the only irreducible eleme ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Atomic Domain

In mathematics, more specifically ring theory, an atomic domain or factorization domain is an integral domain in which every non-zero non-unit can be written in at least one way as a finite product of irreducible elements. Atomic domains are different from unique factorization domains in that this decomposition of an element into irreducibles need not be unique; stated differently, an irreducible element is not necessarily a prime element. Important examples of atomic domains include the class of all unique factorization domains and all Noetherian domains. More generally, any integral domain satisfying the ascending chain condition on principal ideals (ACCP) is an atomic domain. Although the converse is claimed to hold in Cohn's paper, this is known to be false. The term "atomic" is due to P. M. Cohn, who called an irreducible element of an integral domain an "atom". Motivation In this section, a ring can be viewed as merely an abstract set in which one can perform the operati ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |