|

Salomon V Salomon

is a landmark UK company law case. The effect of the House of Lords' unanimous ruling was to uphold firmly the doctrine of corporate personality, as set out in the Companies Act 1862, so that creditors of an insolvent company could not sue the company's shareholders for payment of outstanding debts. Facts Mr. Aron Salomon made leather boots or shoes as a sole proprietor. His sons wanted to become business partners, so he turned the business into a limited liability company. This company purchased Salomon's business at an excessive price for its value. His wife and five elder children became subscribers and the two sons became directors. Mr Salomon took 20,001 of the company's 20,007 shares which were payments from A Salomon & Co Limited for his old business (each share was valued at £1). The transfer of the industry took place on 1 June 1892. The company also issued to Mr Salomon £10,000 in debentures. On the security of his debentures, Mr. Salomon received an advance of £5, ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Judicial Functions Of The House Of Lords

Whilst the House of Lords of the United Kingdom is the upper chamber of Parliament and has government ministers, for many centuries it had a judicial function. It functioned as a court of first instance for the trials of peers and for Impeachment in the United Kingdom, impeachments, and as a court of last resort in the United Kingdom and prior, the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of England. Appeals were technically not to the House of Lords, but rather to the King-in-Parliament. In Appellate Jurisdiction Act 1876, 1876, the Appellate Jurisdiction Act devolved the appellate functions of the House to an Appellate Committee, composed of Lord of Appeal in Ordinary, Lords of Appeal in Ordinary (informally referred to as Law Lords). They were then appointed by the Lord Chancellor in the same manner as other judges. During the 20th and early 21st century, the judicial functions were gradually removed. Its final trial of a peer was in 1935, and the use of special courts for ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Trustee

Trustee (or the holding of a trusteeship) is a legal term which, in its broadest sense, refers to anyone in a position of trust and so can refer to any individual who holds property, authority, or a position of trust or responsibility for the benefit of another. A trustee can also be a person who is allowed to do certain tasks but not able to gain income.''Black's Law Dictionary, Fifth Edition'' (1979), p. 1357, . Although in the strictest sense of the term a trustee is the holder of property on behalf of a beneficiary, the more expansive sense encompasses persons who serve, for example, on the board of trustees of an institution that operates for a charity, for the benefit of the general public, or a person in the local government. A trust can be set up either to benefit particular persons or for any charitable purposes (but not generally for non-charitable purposes): typical examples are a will trust for the testator's children and family, a pension trust (to confer bene ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Preferential Payments In Bankruptcy Amendment Act 1897

The Preferential Payments in Bankruptcy Amendment Act 1897 ( 60 & 61 Vict. c. 19) was an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom, affecting UK insolvency law. It amended the category of " preferential payments" for rates, taxes and wages, to take priority over a floating charge in an insolvent company's assets. The Act was passed in broad response to the decision of the House of Lords in . at paragraph 132, per Lord Walker: "''Saloman v Saloman & Co Ltd'' was decided by this House on 16 November 1896. WIth remarkable promptness Parliament responded by enacting sections 2 and 3 of the Preference Payments in Bankrtupcy Amendment Act 1897". Section 1 of the Preferential Payments in Bankruptcy Act 1888 ( 51 & 52 Vict. c. 62) first introduced the concept. It was amended by section 2 of the Preferential Payments in Bankruptcy Amendment Act 1897. The provisions were re-enacted in the Companies (Consolidation) Act 1908, the Companies Act 1929 and the Companies Act 1948. Its provis ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Trade Creditor

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market. Traders generally negotiate through a medium of credit or exchange, such as money. Though some economists characterize barter (i.e. trading things without the use of money) as an early form of trade, money was invented before written history began. Consequently, any story of how money first developed is mostly based on conjecture and logical inference. Letters of credit, paper money, and non-physical money have greatly simplified and promoted trade as buying can be separated from selling, or earning. Trade between two traders is called bilateral trade, while trade involving more than two traders is called multilateral trade. In one modern view, trade exists due to specialization and the division of labor, a predominant form of economic activity in which individuals and groups concentra ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Floating Charge

In finance, a floating charge is a security interest over a fund of changing assets of a company or other legal person. Unlike a fixed charge, which is created over ascertained and definite property, a floating charge is created over property of an ambulatory and shifting nature, such as receivables and stock. The floating charge 'floats' or 'hovers' until the point at which it is converted ("crystallised") into a ''fixed charge'', attached to specific assets of the business. This crystallisation can be triggered by a number of events. In most common law jurisdictions it is an implied term in the security documents creating floating charges that a cessation of the company's right to deal with the assets (including by reason of insolvency proceedings) in the ordinary course of business leads to automatic crystallisation. Additionally, security documents will usually include express terms that a default by the person granting the security will trigger crystallisation. In most ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

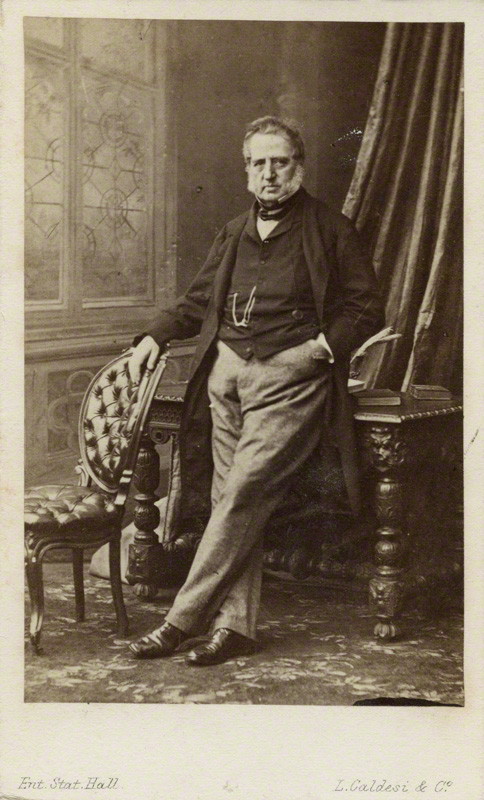

Richard Malins

Sir Richard Malins (9 March 1805 – 15 January 1882) was an English barrister, judge, and politician. Early life The third son of William Malins of Ailston, Warwickshire, by his wife Mary, eldest daughter of Thomas Hunter of Pershore, Worcestershire, and was born at Evesham on 9 March 1805. He was educated at a private school, and then entered Caius College, Cambridge in 1823, where he graduated B.A. in 1827. He had already joined the Inner Temple in 1825, and was called to the bar 14 May 1830. Malins practised as an equity draughtsman and conveyancer in Fig Tree Court, Temple, and later in New Square and in Stone Buildings, Lincoln's Inn. He made his way professionally without backing, interest, concentrated on real property law and the interpretation of wills, and built up a court practice in equity. He trained in his chambers numerous pupils, including Hugh Cairns who was his assistant for some time. In 1849 Malins transferred his membership from the Inner Temple to Linc ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Statute

A statute is a law or formal written enactment of a legislature. Statutes typically declare, command or prohibit something. Statutes are distinguished from court law and unwritten law (also known as common law) in that they are the expressed will of a legislative body, whether that be on the behalf of a country, state or province, county, municipality, or so on. Depending on the legal system, a statute may also be referred to as an "act." Etymology The word appears in use in English as early as the 14th century. "Statute" and earlier English spellings were derived from the Old French words ''statut'', ''estatut'', ''estatu,'' meaning "(royal) promulgation, (legal) statute." These terms were in turn derived from the Late Latin ''statutum,'' meaning "a law, decree." Publication and organization In virtually all countries, newly enacted statutes are published and distributed so that everyone can look up the statutory law. This can be done in the form of a government gazette, whi ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Edward Macnaghten, Baron Macnaghten

Edward Macnaghten, Baron Macnaghten, (3 February 1830 – 17 February 1913) was an Anglo-Irish law lord, barrister, rower, and Conservative- Unionist politician. Early life and rowing Macnaghten was born in Bloomsbury, London, the second son of Sir Edmund Workman-Macnaghten, Bt., but grew up mainly at Roe Park, Limavady. He attended school in Sunderland and university at Trinity College Dublin and Trinity College, Cambridge, graduating Bachelor of Arts in 1852. At Cambridge, he was secretary of the Pitt Club. Macnaghten was a rower at Cambridge. In 1851, he was runner up to E. G. Peacock in the Diamond Challenge Sculls at Henley Royal Regatta, but avenged this the following year with a win. Macnaghten rowed bow for Cambridge in the Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race in 1852 which was won by Oxford. Also in 1852, he turned the tables on Peacock to win the Diamond Challenge Sculls from him at Henley. Legal and political career After being called to the Bar by Lincoln's Inn in 1 ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Macnaghten E Vanity Fair 1895-10-31

Macnaghten may refer to: * Anne Macnaghten (1908–2000), British violinist * Clan Macnaghten * Daniel M'Naghten, namesake of the M'Naghten rules The M'Naghten rule(s) (pronounced, and sometimes spelled, McNaughton) is a legal test (law), test defining the Insanity defense, defence of insanity that was formulated by the House of Lords in 1843. It is the established standard in UK crimina ... * Edward Macnaghten * Elliot Macnaghten * Sir Francis Workman Macnaghten, 1st Baronet (1763–1843), judge in India, father of Elliot Macnaghten and William Hay Macnaghten * Half Hung MacNaghten * Macnaghten baronets of Bushmills House (1836) * Malcolm Macnaghten * Melville Macnaghten * William Hay Macnaghten (1793–1841), British diplomat killed in the First Anglo-Afghan War See also * Macnaughtan * McNaughton {{Disambiguation, surname ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Farrer Herschell, 1st Baron Herschell

Farrer Herschell, 1st Baron Herschell, (2 November 1837 – 1 March 1899), was Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain in 1886, and again from 1892 to 1895. Life Childhood and education Herschell was born on 2 November 1837 in Brampton, Hampshire. His parents were Helen Skirving Mowbray and the Rev. Ridley Haim Herschell, who was a native of Strzelno, in Prussian Poland. When Ridley was a young man, he converted from Judaism to Christianity and took a leading part in founding the British Society for the Propagation of the Gospel Among the Jews. He eventually settled down to the charge of a Nonconformist chapel near the Edgware Road, in London, where he ministered to a large congregation. Farrer was educated at a grammar school in South London and attended lectures at the University of Bonn as a teenager, where his family lived for six months in 1852. In 1857 he took his BA degree with honours in Greek and mathematics at University College London, receiving prizes in logi ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Lindley LJ

Nathaniel Lindley, Baron Lindley, (29 November 1828 – 9 December 1921) was an English judge. Early life He was the second son of the botanist Dr. John Lindley, born at Acton Green, London. From his mother's side, he was descended from Sir Edward Coke. He was educated at University College School, and studied for a time at University College London, and the University of Edinburgh and University of Cambridge in 1898 and achieved Doctor of Civil Law in University of Oxford in 1903. Legal career He was called to the bar at the Middle Temple in 1850, and began practice in the Court of Chancery. In 1855 he published ''An Introduction to the Study of Jurisprudence'', consisting of a translation of the general part of Thibaut's ''System des Pandekten Rechts'', with copious notes. In 1860 he published in two volumes his ''Treatise on the Law of Partnership, including its Application to Joint Stock and other Companies'', and in 1862 a supplement including the Companies Act 1862. This ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Hardinge Stanley Giffard, 1st Earl Of Halsbury

Hardinge Stanley Giffard, 1st Earl of Halsbury (3 September 1823 – 11 December 1921) was a British barrister and Conservative politician. He served three times as Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, for a total of seventeen years, a record not equalled by anyone except Lords Hardwicke and Eldon. The son of a newspaper editor, Giffard was called to the English bar in 1850 and acquired a large criminal practice, defending the likes of Governor Eyre and Arthur Orton, the Tichborne claimant. He was chosen as solicitor-general by Disraeli in 1874, despite not securing a seat in the House of Commons until three years later. In 1885, he was appointed to the lord chancellorship by Lord Salisbury, and was created Baron Halsbury, serving until the following year. He then held the lord chancellorship again from 1886 until 1892, and from 1895 until 1905, when he resigned, aged 86. In 1898, he was further honoured with an earldom and a viscounty, becoming the Earl of Halsbury. ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |