|

Pariwhero Red Rocks

Pariwhero / Red Rocks is a geological formation located in a Scientific reserves of New Zealand, scientific reserve on the south coast of Wellington, New Zealand. The site has been classified as nationally significant, and of high educational and scientific importance. The reserve provides examples of a wide range of rock formations and geological processes that are representative of the earliest stages in the formation of New Zealand. History Pariwhero has been known to Māori people, Māori from the earliest times of Māori occupation in the area, with Māori having multiple explanations for the red colour of the rocks. One of these accounts is that the legendary explorer Kupe left the Wellington area, crossing Te Moana-a-Raukawa (Cook Strait) as he left. His long absence caused his relatives to become worried, with one of his daughters leaping from a cliff on the south coast in her distress, staining the rocks below with her blood. In another account, Kupe was gathering the s ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Wellington

Wellington is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the third-largest city in New Zealand (second largest in the North Island), and is the administrative centre of the Wellington Region. It is the world's southernmost capital of a sovereign state. Wellington features a temperate maritime climate, and is the world's windiest city by average wind speed. Māori oral tradition tells that Kupe discovered and explored the region in about the 10th century. The area was initially settled by Māori iwi such as Rangitāne and Muaūpoko. The disruptions of the Musket Wars led to them being overwhelmed by northern iwi such as Te Āti Awa by the early 19th century. Wellington's current form was originally designed by Captain William Mein Smith, the first Surveyor General for Edward Wakefield's New Zealand Company, in 1840. Smith's plan included a series of inter ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

GNS Science

GNS Science (), officially registered as the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, is a New Zealand Crown Research Institute. It focuses on geology, geophysics (including seismology and volcanology), and nuclear science (particularly ion-beam technologies, isotope science and carbon dating). From 1 July 2025 GNS Science will become part of the new Public Research Organisation New Zealand Institute for Earth Science. Functions and responsibilities As well as undertaking basic research, and operating the national geological hazards monitoring network ( GeoNet) and the National Isotope Centre (NIC), GNS Science contracts its services to various private groups (notably energy companies) both in New Zealand and overseas, as well as to central and local government agencies, to provide scientific advice and information. GNS Science has its head office in Avalon, Lower Hutt, with other facilities in Gracefield, Dunedin, Wairakei, Auckland and Tokyo Tokyo, ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Iron(III)

In chemistry, iron(III) or ''ferric'' refers to the element iron in its +3 oxidation state. ''Ferric chloride'' is an alternative name for iron(III) chloride (). The adjective ''ferrous'' is used instead for iron(II) salts, containing the cation Fe2+. The word ''ferric'' is derived from the Latin word , meaning "iron". Although often abbreviated as Fe3+, that naked ion does not exist except under extreme conditions. Iron(III) centres are found in many compounds and coordination complexes, where Fe(III) is bonded to several ligands. A molecular ferric complex is the anion ferrioxalate, , with three bidentate oxalate ions surrounding the Fe core. Relative to lower oxidation states, ferric is less common in organoiron chemistry, but the ferrocenium cation is well known. Iron(III) in biology All known forms of life require iron, which usually exists in Fe(II) or Fe(III) oxidation states. Many proteins in living beings contain iron(III) centers. Examples of such metalloprot ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Boulder At Red Rocks Scientific Reserve

In geology, a boulder (or rarely bowlder) is a rock fragment with size greater than in diameter. Smaller pieces are called cobbles and pebbles. While a boulder may be small enough to move or roll manually, others are extremely massive. In common usage, a boulder is too large for a person to move. Smaller boulders are usually just called rocks or stones. Etymology The word ''boulder'' derives from ''boulder stone'', from Middle English ''bulderston'' or Swedish ''bullersten''. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved December 9, 2011, from Dictionary.com website. About In places covered by s during |

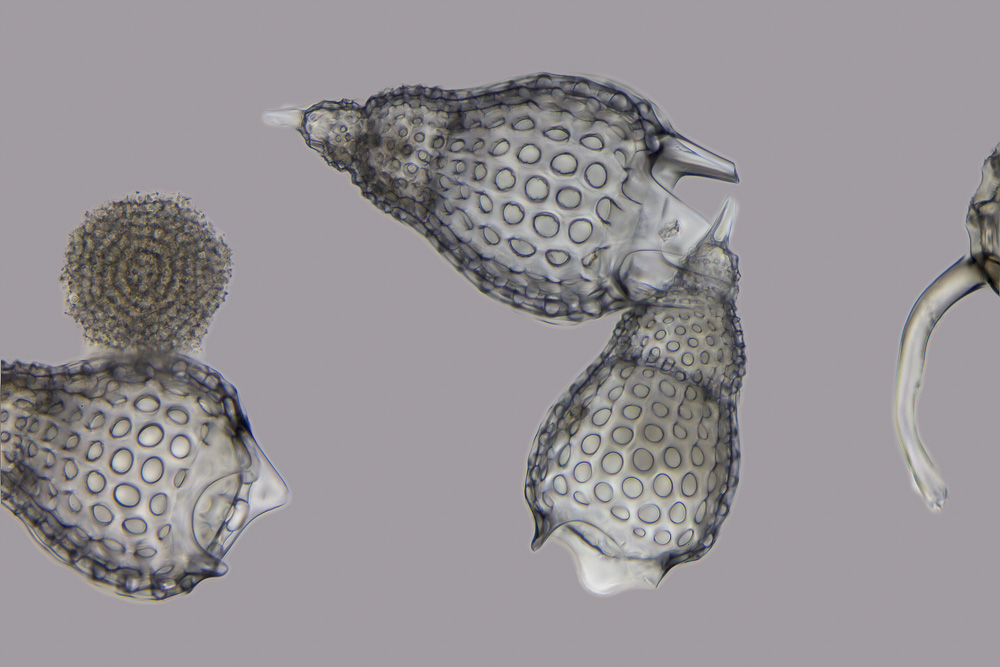

Radiolaria

The Radiolaria, also called Radiozoa, are unicellular eukaryotes of diameter 0.1–0.2 mm that produce intricate mineral skeletons, typically with a central capsule dividing the cell into the inner and outer portions of endoplasm and ectoplasm. The elaborate mineral skeleton is usually made of silica. They are found as zooplankton throughout the global ocean. As zooplankton, radiolarians are primarily heterotrophic, but many have photosynthetic endosymbionts and are, therefore, considered mixotrophs. The skeletal remains of some types of radiolarians make up a large part of the cover of the ocean floor as siliceous ooze. Due to their rapid change as species and intricate skeletons, radiolarians represent an important diagnostic fossil found from the Cambrian onwards. Description Radiolarians have many needle-like pseudopods supported by bundles of microtubules, which aid in the radiolarian's buoyancy. The cell nucleus and most other organelles are in the endoplasm, wh ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Lopingian

The Lopingian is the uppermost series/last epoch of the Permian. It is the last epoch of the Paleozoic. The Lopingian was preceded by the Guadalupian and followed by the Early Triassic. The Lopingian is often synonymous with the informal terms late Permian or upper Permian. The name was introduced by Amadeus William Grabau in 1931 and derives from Leping, Jiangxi in China. It consists of two stages/ ages. The earlier is the Wuchiapingian and the later is the Changhsingian. The International Chronostratigraphic Chart (v2018/07) provides a numerical age of 259.1 ±0.5 Ma. If a Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) has been approved, the lower boundary of the earliest stage determines numerical age of an epoch. The GSSP for the Wuchiapingian has a numerical age of 259.8 ± 0.4 Ma. Evidence from Milankovitch cycles suggests that the length of an Earth day during this epoch was approximately 22 hours. Geography During the Lopingian, most of the earth was ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Late Triassic

The Late Triassic is the third and final epoch (geology), epoch of the Triassic geologic time scale, Period in the geologic time scale, spanning the time between annum, Ma and Ma (million years ago). It is preceded by the Middle Triassic Epoch and followed by the Early Jurassic Epoch. The corresponding series (stratigraphy), series of rock beds is known as the Upper Triassic. The Late Triassic is divided into the Carnian, Norian and Rhaetian Geologic time scale, ages. Many of the first dinosaurs evolved during the Late Triassic, including ''Plateosaurus'', ''Coelophysis'', ''Herrerasaurus'', and ''Eoraptor''. The Triassic–Jurassic extinction event began during this epoch and is one of the five major mass extinction events of the Earth. Etymology The Triassic was named in 1834 by Friedrich August von Namoh, Friedrich von Alberti, after a succession of three distinct rock layers (Greek meaning 'triad') that are widespread in southern Germany: the lower Buntsandstein (colourful ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

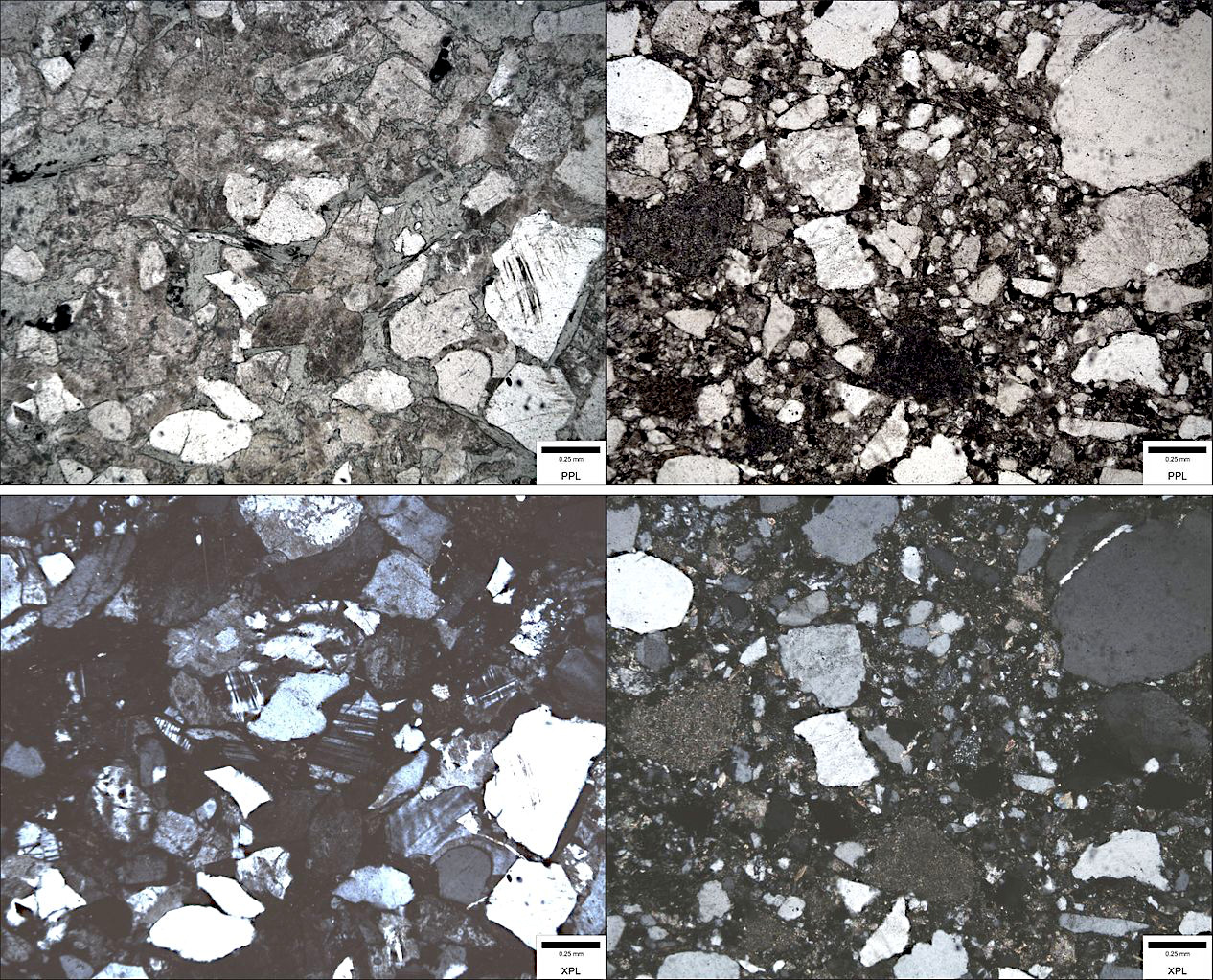

Greywacke

Greywacke or graywacke ( ) is a variety of sandstone generally characterized by its hardness (6–7 on Mohs scale), dark color, and Sorting (sediment), poorly sorted angular grains of quartz, feldspar, and small rock fragments or sand-size Lithic fragment (geology), lithic fragments set in a compact, clay-fine matrix. It is a texturally immature sedimentary rock generally found in Paleozoic Stratum, strata. The larger Particle size (grain size), grains can be sand- to gravel-sized, and Matrix (geology), matrix materials generally constitute more than 15% of the rock by volume. Formation The origin of greywacke was unknown until turbidity currents and turbidites were understood, since, according to the normal laws of sedimentation, gravel, sand and mud should not be laid down together. Geologists now attribute its formation to submarine avalanches or strong turbidity currents. These actions churn sediment and cause mixed-sediment slurries, in which the resulting deposits may ex ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Bed (geology)

In geology, a bed is a layer of sediment, sedimentary rock, or volcanic rock "bounded above and below by more or less well-defined bedding surfaces".Neuendorf, K.K.E., J.P. Mehl, Jr., and J.A. Jackson, eds., 2005. ''Glossary of Geology'' (5th ed.). Alexandria, Virginia; American Geological Institute. p 61. A bedding surface or bedding plane is respectively a curved surface or Euclidean planes in three-dimensional space, plane that visibly separates each successive bed (of the same or different lithology) from the preceding or following bed. In Cross section (geology), cross sections, bedding surfaces or planes are often called bedding contacts. Within conformable successions, each bedding surface acted as the depositional surface for the accumulation of younger sediment. Definitions Specifically in sedimentology, a bed can be defined in one of two major ways.Davies, N.S., and Shillito, A.P. 2021, ''True substrates: the exceptional resolution and unexceptional preservation of de ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Fault (geology)

In geology, a fault is a Fracture (geology), planar fracture or discontinuity in a volume of Rock (geology), rock across which there has been significant displacement as a result of rock-mass movements. Large faults within Earth's crust (geology), crust result from the action of Plate tectonics, plate tectonic forces, with the largest forming the boundaries between the plates, such as the megathrust faults of subduction, subduction zones or transform faults. Energy release associated with rapid movement on active faults is the cause of most earthquakes. Faults may also displace slowly, by aseismic creep. A ''fault plane'' is the Plane (geometry), plane that represents the fracture surface of a fault. A ''fault trace'' or ''fault line'' is a place where the fault can be seen or mapped on the surface. A fault trace is also the line commonly plotted on geological maps to represent a fault. A ''fault zone'' is a cluster of parallel faults. However, the term is also used for the zone ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Siltstone

Siltstone, also known as aleurolite, is a clastic sedimentary rock that is composed mostly of silt. It is a form of mudrock with a low clay mineral content, which can be distinguished from shale by its lack of fissility. Although its permeability and porosity is relatively low, siltstone is sometimes a tight gas reservoir rock, an unconventional reservoir for natural gas that requires hydraulic fracturing for economic gas production. Siltstone was prized in ancient Egypt for manufacturing statuary and cosmetic palettes. The siltstone quarried at Wadi Hammamat was a hard, fine-grained siltstone that resisted flaking and was almost ideal for such uses. Description There is not complete agreement on the definition of siltstone. One definition is that siltstone is mudrock (clastic sedimentary rock containing at least 50% clay and silt) in which at least 2/3 of the clay and silt fraction is composed of silt-sized particles. Silt is defined as grains 2–62 μm in diam ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Chert

Chert () is a hard, fine-grained sedimentary rock composed of microcrystalline or cryptocrystalline quartz, the mineral form of silicon dioxide (SiO2). Chert is characteristically of biological origin, but may also occur inorganically as a precipitation (chemistry), chemical precipitate or a diagenesis, diagenetic replacement, as in petrified wood. Chert is typically composed of the petrified remains of siliceous ooze, the biogenic sediment that covers large areas of the deep ocean floor, and which contains the silicon skeletal remains of diatoms, Dictyochales, silicoflagellates, and radiolarians. Precambrian cherts are notable for the presence of fossil cyanobacteria. In addition to Micropaleontology, microfossils, chert occasionally contains macrofossils. However, some chert is devoid of any fossils. Chert varies greatly in color, from white to black, but is most often found as gray, brown, grayish brown and light green to rusty redW.L. Roberts, T.J. Campbell, G.R. Rapp Jr., ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |