|

1840 In Science

The year 1840 in science and technology involved some significant events, listed below. Events * William Whewell publishes ''The Philosophy of the Inductive Sciences'', introducing the terms ''scientist'' (for the second time) and ''physicist''. * Justus von Liebig publishes ''Die Organische Chemie in ihre Anwendung auf Agricultur und Physiologie'' in Braunschweig, emphasising the importance of agricultural chemistry in crop production; it will go through at least eight editions. * The first known photograph of Niagara Falls, a daguerreotype, is taken by English chemist Hugh Lee Pattinson. Astronomy * John William Draper invents astronomical photography and photographs the Moon. Biology * John Gould begins publication of '' The Birds of Australia''. Chemistry * Germain Hess proposes Hess's law, an early statement of the law of conservation of energy, which establishes that energy changes in a chemical process depend only on the states of the starting and product materials a ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

The Birds Of Australia (Gould)

''The Birds of Australia'' is a book written by John Gould and published in seven volumes between 1840 and 1848, with a supplement published between 1851 and 1869. It was the first comprehensive survey of the birds of Australia and included descriptions of 681 species, 328 of which were new to Western science and were first described by Gould. Gould and his wife Elizabeth Gould (illustrator), Elizabeth ''née'' Coxen travelled to Australia from England in 1838 to prepare the book. They spent a little under two years collecting specimens for the book. John travelled widely and made extensive collections of Australian birds and other fauna. Elizabeth, who had illustrated several of his earlier works, made hundreds of drawings from specimens for publication in ''The Birds of Australia.'' The plates of the book were produced by lithography, and have been hand-coloured by Gabriel Bayfield's studio. Elizabeth produced 84 plates before she died in 1841, Edward Lear produced one, Benjami ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

The Great Devonian Controversy

The Great Devonian Controversy began in 1834 when Roderick Murchison disagreed with Henry De la Beche as to the dating of certain petrified plants found in coals in the Greywacke stratum in North Devon, England. De La Beche was claiming that since Carboniferous fossils were found deep in the Greywacke stratum, which itself was older than the Carboniferous period, this method of dating rocks was not valid. Murchison, in contrast, claimed that De La Beche had not placed the fossils correctly, as they were occurring quite near the top of the stratum as opposed to deep within it. De La Beche soon agreed with Murchison's argument as to the placing of fossils but maintained that since a layer of Old Red Sandstone, present in other formations, was missing between the layer of older rock and this new formation, there was still insufficient evidence to suggest the formation was not part of the older Silurian strata. There followed much debate and some extensive investigations which rang ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a period (geology), geologic period and system (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era during the Phanerozoic eon (geology), eon, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the preceding Silurian period at million years ago (Megaannum, Ma), to the beginning of the succeeding Carboniferous period at Ma. It is the fourth period of both the Paleozoic and the Phanerozoic. It is named after Devon, South West England, where rocks from this period were first studied. The first significant evolutionary radiation of history of life#Colonization of land, life on land occurred during the Devonian, as free-spore, sporing land plants (pteridophytes) began to spread across dry land, forming extensive coal forests which covered the continents. By the middle of the Devonian, several groups of vascular plants had evolved leaf, leaves and true roots, and by the end of the period the first seed-bearing plants (Pteridospermatophyta, pteridospermatophyt ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Roderick Murchison

Sir Roderick Impey Murchison, 1st Baronet (19 February 1792 – 22 October 1871) was a Scottish geologist who served as director-general of the British Geological Survey from 1855 until his death in 1871. He is noted for investigating and describing the Silurian, Devonian and Permian systems. Early life and work Murchison was born at Tarradale House, Muir of Ord, Ross-shire, the son of Barbara and Kenneth Murchison. His wealthy father died in 1796, when Roderick was four years old, and he was sent to Durham School three years later and then to the Royal Military College, Great Marlow, to be trained for the army. In 1808, under Wellesley, he landed in Portugal, and was present at the actions of Roliça and Vimeiro in the Peninsular War as an ensign in the 36th Regt of Foot. Subsequently, under Sir John Moore, he took part in the retreat to Corunna and the final battle there. After eight years of service Murchison left the army and married Charlotte Hugonin (1788–1869 ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Ice Age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages, and greenhouse periods during which there are no glaciers on the planet. Earth is currently in the ice age called Quaternary glaciation. Individual pulses of cold climate within an ice age are termed '' glacial periods'' (''glacials, glaciations, glacial stages, stadials, stades'', or colloquially, ''ice ages''), and intermittent warm periods within an ice age are called '' interglacials'' or ''interstadials''. In glaciology, the term ''ice age'' is defined by the presence of extensive ice sheets in the northern and southern hemispheres. By this definition, the current Holocene epoch is an interglacial period of an ice age. The accumulation of anthropogenic greenhouse gases is projected to delay the next glacial period. History of research ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Louis Agassiz

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz ( ; ) FRS (For) FRSE (May 28, 1807 – December 14, 1873) was a Swiss-born American biologist and geologist who is recognized as a scholar of Earth's natural history. Spending his early life in Switzerland, he received a PhD at Erlangen and a medical degree in Munich. After studying with Georges Cuvier and Alexander von Humboldt in Paris, Agassiz was appointed professor of natural history at the University of Neuchâtel. He emigrated to the United States in 1847 after visiting Harvard University. He went on to become professor of zoology and geology at Harvard, to head its Lawrence Scientific School, and to found its Museum of Comparative Zoology. Agassiz is known for observational data gathering and analysis. He made institutional and scientific contributions to zoology, geology, and related areas, including multivolume research books running to thousands of pages. He is particularly known for his contributions to ichthyological classification, incl ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

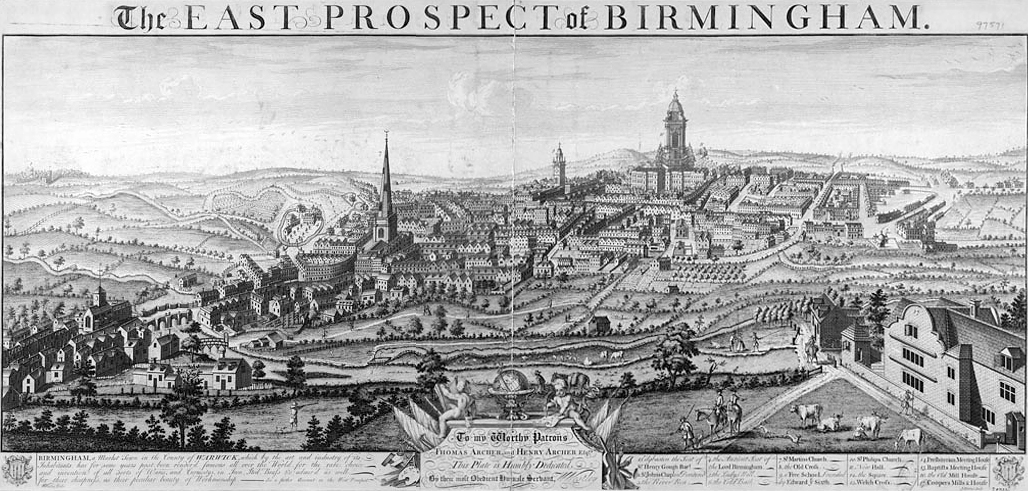

Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands, within the wider West Midlands (region), West Midlands region, in England. It is the List of English districts by population, largest local authority district in England by population and the second-largest city in Britain – commonly referred to as the second city of the United Kingdom – with a population of million people in the city proper in . Birmingham borders the Black Country to its west and, together with the city of Wolverhampton and towns including Dudley and Solihull, forms the West Midlands conurbation. The royal town of Sutton Coldfield is incorporated within the city limits to the northeast. The urban area has a population of 2.65million. Located in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands region of England, Birmingham is considered to be the social, cultural, financial and commercial centre of the Midland ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

John Wright (inventor)

John Wright (1808–1844) was a surgeon from Birmingham, England who invented a process of electroplating involving potassium cyanide. The process was patented in 1840 by Wright's associate George Richards Elkington. He was born on the Isle of Sheppey, Kent and was apprenticed to a Dr Spearman in Rotherham, Yorkshire. He then completed his medical training in Edinburgh, Paris and London. He moved to the Bordesley district of Birmingham in 1833, in the centre of the metal working industry, where he experimented with electricity in his spare time. After reading an article by Carl Wilhelm Scheele Carl Wilhelm Scheele (, ; 9 December 1742 – 21 May 1786) was a Swedish Pomerania, German-Swedish pharmaceutical chemist. Scheele discovered oxygen (although Joseph Priestley published his findings first), and identified the elements molybd ... on the behaviour of the cyanides of gold and silver in a solution of potassium cyanide he devised an experiment to test such a solution as ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Electroplating

Electroplating, also known as electrochemical deposition or electrodeposition, is a process for producing a metal coating on a solid substrate through the redox, reduction of cations of that metal by means of a direct current, direct electric current. The part to be coated acts as the cathode (negative electrode) of an electrolytic cell; the electrolyte is a solution (chemistry), solution of a salt (chemistry), salt whose cation is the metal to be coated, and the anode (positive electrode) is usually either a block of that metal, or of some inert electrical conductor, conductive material. The current is provided by an external power supply. Electroplating is widely used in industry and decorative arts to improve the surface qualities of objects—such as resistance to abrasion (mechanical), abrasion and corrosion, lubrication, lubricity, reflectivity, electrical conductivity, or appearance. It is used to build up thickness on undersized or worn-out parts and to manufacture metal ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

Patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an sufficiency of disclosure, enabling disclosure of the invention."A patent is not the grant of a right to make or use or sell. It does not, directly or indirectly, imply any such right. It grants only the right to exclude others. The supposition that a right to make is created by the patent grant is obviously inconsistent with the established distinctions between generic and specific patents, and with the well-known fact that a very considerable portion of the patents granted are in a field covered by a former relatively generic or basic patent, are tributary to such earlier patent, and cannot be practiced unless by license thereunder." – ''Herman v. Youngstown Car Mfg. Co.'', 191 F. 579, 584–85, 112 CCA 185 (6th Cir. 1911) In most countries, patent rights fall under private la ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |

George Richards Elkington

George Richards Elkington (17 October 1801 – 22 September 1865) was a manufacturer from Birmingham, England. He patented the first commercial electroplating process. Biography Elkington was born in Birmingham, the son of a spectacle manufacturer. Apprenticed to his uncles' silver plating business in 1815, he became, on their death, sole proprietor of the business, but subsequently took his cousin, Henry Elkington, into partnership. The science of electrometallurgy was then in its infancy, but the Elkingtons were quick to recognize its possibilities. They had already taken out certain patents for the application of electricity to metals when, in 1840, John Wright, a Birmingham surgeon, discovered the valuable properties of a solution of cyanide of silver in potassium cyanide for electroplating purposes. The Elkingtons purchased and patented Wright's process (British Patent 8447 : Improvements in Coating, Covering, or Plating certain Metals), subsequently acquiring the right ... [...More Info...] [...Related Items...] OR: [Wikipedia] [Google] [Baidu] |