Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after ''

Zion

Zion ( he, צִיּוֹן ''Ṣīyyōn'', LXX , also variously Romanization of Hebrew, transliterated ''Sion'', ''Tzion'', ''Tsion'', ''Tsiyyon'') is a placename in the Hebrew Bible used as a synonym for Jerusalem as well as for the Land of Isra ...

'') is a

nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a

homeland for the Jewish people

A homeland for the Jewish people is an idea rooted in Jewish history, religion, and culture. The Jewish aspiration to return to Zion, generally associated with divine redemption, has suffused Jewish religious thought since the destruction ...

centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Jewish tradition as the

Land of Israel

The Land of Israel () is the traditional Jewish name for an area of the Southern Levant. Related biblical, religious and historical English terms include the Land of Canaan, the Promised Land, the Holy Land, and Palestine (see also Isr ...

, which corresponds in other terms to the

region of Palestine

Palestine ( el, Παλαιστίνη, ; la, Palaestina; ar, فلسطين, , , ; he, פלשתינה, ) is a geographic region in Western Asia. It is usually considered to include Israel and the State of Palestine (i.e. West Bank and Gaza S ...

,

Canaan

Canaan (; Phoenician: 𐤊𐤍𐤏𐤍 – ; he, כְּנַעַן – , in pausa – ; grc-bib, Χανααν – ;The current scholarly edition of the Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus T ...

, or the

Holy Land

The Holy Land; Arabic: or is an area roughly located between the Mediterranean Sea and the Eastern Bank of the Jordan River, traditionally synonymous both with the biblical Land of Israel and with the region of Palestine. The term "Holy ...

, on the basis of a long Jewish connection and attachment to that land.

Modern Zionism emerged in the late 19th century in

Central

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known a ...

and

Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

as a national revival movement, both in reaction to newer waves of

antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

and as a response to

Haskalah

The ''Haskalah'', often termed Jewish Enlightenment ( he, השכלה; literally, "wisdom", "erudition" or "education"), was an intellectual movement among the Jews of Central and Eastern Europe, with a certain influence on those in Western Euro ...

, or Jewish Enlightenment.

Soon after this, most leaders of the movement associated the main goal with creating the desired homeland in Palestine, then an area controlled by the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

.

From 1897 to 1948, the primary goal of the Zionist Movement was to establish the basis for a Jewish homeland in Palestine, and thereafter to consolidate it. In a unique variation of the principle of self-determination, the Zionist Movement viewed this process as an '

ingathering of exiles' (''kibbutz galuyot'') whereby Jews everywhere would have the right to emigrate to historical Palestine, as a haven from persecution, an area which Moses in the

Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus ...

stated was the

land of their forefathers. Zionist ideology also included

negation of Jewish life in the Diaspora. The

Lovers of Zion united in 1884 and in 1897 the first

Zionist congress

The Zionist Congress was established in 1897 by Theodor Herzl as the supreme organ of the Zionist Organization (ZO) and its legislative authority. In 1960 the names were changed to World Zionist Congress ( he, הקונגרס הציוני העו ...

was organized.

A variety of Zionism, called

cultural Zionism, founded and represented most prominently by

Ahad Ha'am

Asher Zvi Hirsch Ginsberg (18 August 1856 – 2 January 1927), primarily known by his Hebrew name and pen name Ahad Ha'am ( he, אחד העם, lit. 'one of the people', Genesis 26:10), was a Hebrew essayist, and one of the foremost pre-state Zi ...

, fostered a

secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin ''saeculum'', "worldly" or "of a generation"), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Anything that does not have an explicit reference to religion, either negativ ...

vision of a Jewish "spiritual center" in Israel. Unlike

Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl; hu, Herzl Tivadar; Hebrew name given at his brit milah: Binyamin Ze'ev (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austro-Hungarian Jewish lawyer, journalist, playwright, political activist, and writer who was the father of modern po ...

, the founder of political Zionism, Ahad Ha'am strived for Israel to be "a Jewish State, and not merely a State of Jews". Others have theorized it as the realization of a socialist utopia (

Moses Hess

Moses (Moritz) Hess (21 January 1812 – 6 April 1875) was a German-Jewish philosopher, early communist and Zionist thinker. His socialist theories led to disagreements with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. He is considered a pioneer of Labor ...

), as a need for survival in the face of social prejudices by the affirmation of

self-determination

The right of a people to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law (commonly regarded as a '' jus cogens'' rule), binding, as such, on the United Nations as authoritative interpretation of the Charter's norms. It sta ...

(

Leon Pinsker

yi, לעאָן פינסקער

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Tomaszów Lubelski, Kingdom of Poland, Russian Empire

, death_date =

, death_place = Odessa, Russian Empire

, known_for = Zionism

, occupation = Physician, political activ ...

), as the fulfillment of

individual rights

Group rights, also known as collective rights, are rights held by a group '' qua'' a group rather than individually by its members; in contrast, individual rights are rights held by individual people; even if they are group-differentiated, which ...

and freedoms (

Max Nordau

Max Simon Nordau (born ''Simon Maximilian Südfeld''; 29 July 1849 – 23 January 1923) was a Zionist leader, physician, author, and social critic.

He was a co-founder of the Zionist Organization together with Theodor Herzl, and president or vic ...

) or as the foundation of a

Hebrew humanism (

Martin Buber

Martin Buber ( he, מרטין בובר; german: Martin Buber; yi, מארטין בובער; February 8, 1878 –

June 13, 1965) was an Austrian Jewish and Israeli philosopher best known for his philosophy of dialogue, a form of existentialism ...

). A

religious Zionist

Religious Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת דָּתִית, translit. ''Tziyonut Datit'') is an ideology that combines Zionism and Orthodox Judaism. Its adherents are also referred to as ''Dati Leumi'' ( "National Religious"), and in Israel, the ...

supports Jews upholding their Jewish identity (defined as adherence to religious Judaism) and has advocated the return of the Jewish people to Israel. Since the establishment of the

State of Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

in 1948, Zionism has continued primarily to advocate on behalf of Israel and to address threats to its continued existence and security.

Advocates of Zionism view it as a national

liberation movement

A liberation movement is an organization or political movement leading a rebellion, or a non-violent social movement, against a colonial power or national government, often seeking independence based on a nationalist identity and an anti-imperial ...

for the repatriation of a persecuted people to its ancestral homeland.

[''Israel Affairs'' - Volume 13, Issue 4, 2007 – Special Issue: ''Postcolonial Theory and the Arab-Israel Conflict – De-Judaizing the Homeland: Academic Politics in Rewriting the History of Palestine'' - S. Ilan Troen]["Zionism and British imperialism II: Imperial financing in Palestine", ''Journal of Israeli History: Politics, Society, Culture''. Volume 30, Issue 2, 2011 - pages 115–139 - Michael J. Cohen] Anti-Zionists

Anti-Zionism is opposition to Zionism. Although anti-Zionism is a heterogeneous phenomenon, all its proponents agree that the creation of the modern State of Israel, and the movement to create a sovereign Jewish state in the region of Palestine ...

view it as a

colonialist

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose their relig ...

,

racist

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism ...

or

exceptionalist ideology or movement.

Terminology

The term "Zionism" is derived from the word ''Zion'' ( he, ציון, ''Tzi-yon''), a hill in

Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

, widely symbolizing the Land of Israel. Throughout eastern Europe in the late 19th century, numerous grassroots groups promoted the national resettlement of the Jews in their homeland, as well as the revitalization and cultivation of the

Hebrew language

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserve ...

. These groups were collectively called the "

Lovers of Zion" and were seen as countering a growing Jewish movement toward assimilation. The first use of the term is attributed to the Austrian

Nathan Birnbaum, founder of the Kadimah nationalist Jewish students' movement; he used the term in 1890 in his journal ''Selbstemanzipation!'' (''Self-Emancipation''), itself named almost identically to

Leon Pinsker

yi, לעאָן פינסקער

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Tomaszów Lubelski, Kingdom of Poland, Russian Empire

, death_date =

, death_place = Odessa, Russian Empire

, known_for = Zionism

, occupation = Physician, political activ ...

's 1882 book ''

Auto-Emancipation

upThe book "Auto-Emancipation" by Pinsker, 1882

''Auto-Emancipation'' (''Selbstemanzipation'') is a pamphlet written in German by Russian-Polish Jewish doctor and activist Leo Pinsker in 1882. It is considered a founding document of modern Jewis ...

''.

Overview

The common denominator among all Zionists has been a claim to Palestine, a land traditionally known in Jewish writings as the

Land of Israel

The Land of Israel () is the traditional Jewish name for an area of the Southern Levant. Related biblical, religious and historical English terms include the Land of Canaan, the Promised Land, the Holy Land, and Palestine (see also Isr ...

("''Eretz Israel''") as a national homeland of the Jews and as the legitimate focus for Jewish national self-determination. It is based on historical ties and

religious traditions linking the Jewish people to the Land of Israel. Zionism does not have a uniform ideology, but has evolved in a dialogue among a plethora of ideologies: General Zionism,

Religious Zionism

Religious Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת דָּתִית, translit. ''Tziyonut Datit'') is an ideology that combines Zionism and Orthodox Judaism. Its adherents are also referred to as ''Dati Leumi'' ( "National Religious"), and in Israel, th ...

,

Labor Zionism

Labor Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת סוֹצְיָאלִיסְטִית, ) or socialist Zionism ( he, תְּנוּעָת הָעַבוֹדָה, label=none, translit=Tnuʽat haʽavoda) refers to the left-wing, socialist variation of Zionism ...

,

Revisionist Zionism

Revisionist Zionism is an ideology developed by Ze'ev Jabotinsky, who advocated a "revision" of the "practical Zionism" of David Ben-Gurion and Chaim Weizmann which was focused on the settling of ''Eretz Yisrael'' (Land of Israel) by independent ...

,

Green Zionism

Green Zionism is a branch of Zionism that is primarily concerned with the environment of Israel. It mostly fuses Israeli-specific environmental concerns with support for the existence of Israel as a Jewish state. The term itself is a trademark o ...

, etc.

After almost two millennia of the

Jewish diaspora

The Jewish diaspora ( he, תְּפוּצָה, təfūṣā) or exile (Hebrew: ; Yiddish: ) is the dispersion of Israelites or Jews out of their ancient ancestral homeland (the Land of Israel) and their subsequent settlement in other parts of th ...

residing in various countries without a national state, the Zionist movement was founded in the late 19th century by

secular Jews, largely as a response by

Ashkenazi Jews

Ashkenazi Jews ( ; he, יְהוּדֵי אַשְׁכְּנַז, translit=Yehudei Ashkenaz, ; yi, אַשכּנזישע ייִדן, Ashkenazishe Yidn), also known as Ashkenazic Jews or ''Ashkenazim'',, Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation: , singu ...

to rising antisemitism in Europe, exemplified by the

Dreyfus affair

The Dreyfus affair (french: affaire Dreyfus, ) was a political scandal that divided the French Third Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. "L'Affaire", as it is known in French, has come to symbolise modern injustice in the Francop ...

in France and the

anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Ant ...

. The political movement was formally established by the

Austro-Hungarian

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1 ...

journalist

Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl; hu, Herzl Tivadar; Hebrew name given at his brit milah: Binyamin Ze'ev (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austro-Hungarian Jewish lawyer, journalist, playwright, political activist, and writer who was the father of modern po ...

in 1897 following the publication of his book ''

Der Judenstaat

''Der Judenstaat'' (German, literally ''The State of the Jews'', commonly rendered as ''The Jewish State'') is a pamphlet written by Theodor Herzl and published in February 1896 in Leipzig and Vienna by M. Breitenstein's Verlags-Buchhandlung. It ...

'' (''The Jewish State''). At that time, the movement sought to encourage Jewish migration to

Ottoman Palestine particularly among those Jewish communities who were poor,

unassimilated and whose 'floating' presence caused disquiet, in Herzl's view, among assimilated Jews and stirred anti-Semitism among Christians.

Although initially one of several Jewish political movements offering alternative responses to Jewish assimilation and antisemitism, Zionism expanded rapidly. In its early stages, supporters considered setting up a Jewish state in the historic territory of Palestine. After

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

and the destruction of Jewish life in Central and Eastern Europe where these alternative movements were rooted, it became dominant in the thinking about a Jewish national state.

Creating an alliance with

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

and securing support for some years for Jewish emigration to Palestine, Zionists also recruited European Jews to immigrate there, especially Jews who lived in areas of the Russian Empire where anti-semitism was raging. The alliance with Britain was strained as the latter realized the implications of the Jewish movement for Arabs in Palestine, but the Zionists persisted. The movement was eventually successful in establishing Israel on May 14, 1948 (5 Iyyar 5708 in the

Hebrew calendar

The Hebrew calendar ( he, הַלּוּחַ הָעִבְרִי, translit=HaLuah HaIvri), also called the Jewish calendar, is a lunisolar calendar used today for Jewish religious observance, and as an official calendar of the state of Israel ...

), as the

homeland for the Jewish people

A homeland for the Jewish people is an idea rooted in Jewish history, religion, and culture. The Jewish aspiration to return to Zion, generally associated with divine redemption, has suffused Jewish religious thought since the destruction ...

. The proportion of the world's Jews living in Israel has steadily grown since the movement emerged. By the early 21st century, more than 40% of the

world's Jews lived in Israel, more than in any other country. These two outcomes represent the historical success of Zionism and are unmatched by any other Jewish political movement in the past 2,000 years. In some academic studies, Zionism has been analyzed both within the larger context of

diaspora politics

Diaspora politics is the political behavior of transnational ethnic diasporas, their relationship with their ethnic homelands and their host states, and their prominent role in ethnic conflicts. Shain, Yossi & Tamara Cofman Wittes. Peace as a Th ...

and as an example of modern

national liberation movements

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, ...

.

Zionism also sought the assimilation of Jews into the modern world. As a result of the diaspora, many of the Jewish people remained outsiders within their adopted countries and became detached from modern ideas. So-called "assimilationist" Jews desired complete integration into European society. They were willing to downplay their Jewish identity and in some cases to abandon traditional views and opinions in an attempt at modernization and assimilation into the modern world. A less extreme form of assimilation was called cultural synthesis. Those in favor of cultural synthesis desired continuity and only moderate evolution, and were concerned that Jews should not lose their identity as a people. "Cultural synthesists" emphasized both a need to maintain traditional Jewish values and faith and a need to conform to a modernist society, for instance, in complying with work days and rules.

In 1975, the

United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Curr ...

passed

Resolution 3379, which designated Zionism as "a form of racism and racial discrimination". The resolution was repealed in 1991 by replacing Resolution 3379 with

Resolution 46/86. Opposition to Zionism (being against a Jewish state), according to historian

Geoffrey Alderman

Geoffrey Alderman (born 10 February 1944) is a British historian that specialises in 19th and 20th centuries Jewish community in England. He is also a political adviser and journalist.

Life

Born in Middlesex, Alderman was educated at Hackney D ...

, can be legitimately described as racist.

Beliefs

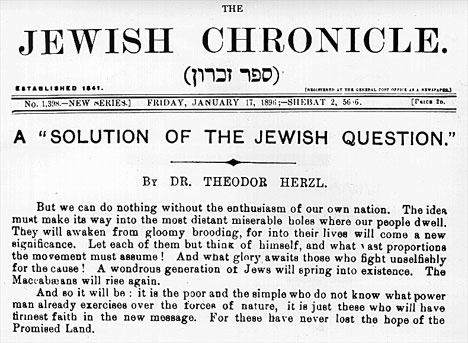

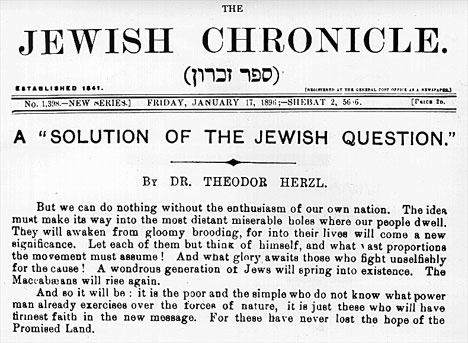

In 1896,

Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl; hu, Herzl Tivadar; Hebrew name given at his brit milah: Binyamin Ze'ev (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austro-Hungarian Jewish lawyer, journalist, playwright, political activist, and writer who was the father of modern po ...

expressed in ''

Der Judenstaat

''Der Judenstaat'' (German, literally ''The State of the Jews'', commonly rendered as ''The Jewish State'') is a pamphlet written by Theodor Herzl and published in February 1896 in Leipzig and Vienna by M. Breitenstein's Verlags-Buchhandlung. It ...

'' his views on "the restoration of the Jewish state". Herzl considered

Antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

to be an eternal feature of all societies in which Jews lived as minorities, and that only a sovereignty could allow Jews to escape eternal persecution : "Let them give us sovereignty over a piece of the Earth's surface, just sufficient for the needs of our people, then we will do the rest!" he proclaimed exposing his plan.

Aliyah (migration, literally "ascent") to the Land of Israel is a recurring theme in Jewish prayers.

Rejection of life in the Diaspora is a central assumption in Zionism. Some supporters of Zionism believed that Jews in the Diaspora were prevented from their full growth in Jewish individual and national life.

Zionists generally preferred to speak

Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

, a

Semitic language

The Semitic languages are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They are spoken by more than 330 million people across much of West Asia, the Horn of Africa, and latterly North Africa, Malta, West Africa, Chad, and in large immigrant ...

which flourished as a spoken language in the ancient

Kingdoms of Israel and Judah

The history of ancient Israel and Judah begins in the Southern Levant during the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age. "Israel" as a people or tribal confederation (see Israelites) appears for the first time in the Merneptah Stele, an inscri ...

during the period from about 1200 to 586 BCE, and was largely preserved throughout history as the main

liturgical language

A sacred language, holy language or liturgical language is any language that is cultivated and used primarily in church service or for other religious reasons by people who speak another, primary language in their daily lives.

Concept

A sacr ...

of

Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in th ...

. Zionists worked to modernize Hebrew and adapt it for everyday use. They sometimes refused to speak

Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ve ...

, a language they thought had developed in the context of

European persecution. Once they moved to Israel, many Zionists refused to speak their (diasporic) mother tongues and adopted new, Hebrew names. Hebrew was preferred not only for ideological reasons, but also because it allowed all citizens of the new state to have a common language, thus furthering the political and cultural bonds among Zionists.

Major aspects of the Zionist idea are represented in the

Israeli Declaration of Independence

The Israeli Declaration of Independence, formally the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel ( he, הכרזה על הקמת מדינת ישראל), was proclaimed on 14 May 1948 ( 5 Iyar 5708) by David Ben-Gurion, the Executiv ...

:

History

Historical and religious background

The Jewish people are an

ethnoreligious group

An ethnoreligious group (or an ethno-religious group) is a grouping of people who are unified by a common religious and ethnic background.

Furthermore, the term ethno-religious group, along with ethno-regional and ethno-linguistic groups, is a ...

and

nation

A nation is a community of people formed on the basis of a combination of shared features such as language, history, ethnicity, culture and/or society. A nation is thus the collective identity of a group of people understood as defined by th ...

[ "The Jews are a nation and were so before there was a Jewish state of Israel"][ "Jews are a people, a nation (in the original sense of the word), an ethnos"] originating from the

Israelites

The Israelites (; , , ) were a group of Semitic-speaking tribes in the ancient Near East who, during the Iron Age, inhabited a part of Canaan.

The earliest recorded evidence of a people by the name of Israel appears in the Merneptah Stele o ...

[ Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites"]["The people of the Kingdom of Israel and the ethnic and religious group known as the Jewish people that descended from them have been subjected to a number of forced migrations in their history"] and

Hebrews

The terms ''Hebrews'' (Hebrew: / , Modern: ' / ', Tiberian: ' / '; ISO 259-3: ' / ') and ''Hebrew people'' are mostly considered synonymous with the Semitic-speaking Israelites, especially in the pre-monarchic period when they were still ...

of historical

Israel and Judah

The history of ancient Israel and Judah begins in the Southern Levant during the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age. "Israel" as a people or tribal confederation (see Israelites) appears for the first time in the Merneptah Stele, an inscripti ...

, two

Israelite

The Israelites (; , , ) were a group of Semitic-speaking tribes in the ancient Near East who, during the Iron Age, inhabited a part of Canaan.

The earliest recorded evidence of a people by the name of Israel appears in the Merneptah Stel ...

kingdoms that emerged in the

Southern Levant

The Southern Levant is a geographical region encompassing the southern half of the Levant. It corresponds approximately to modern-day Israel, Palestine, and Jordan; some definitions also include southern Lebanon, southern Syria and/or the Sinai P ...

during the

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly ...

. Jews are named after the

Kingdom of Judah

The Kingdom of Judah ( he, , ''Yəhūdā''; akk, 𒅀𒌑𒁕𒀀𒀀 ''Ya'údâ'' 'ia-ú-da-a-a'' arc, 𐤁𐤉𐤕𐤃𐤅𐤃 ''Bēyt Dāwīḏ'', " House of David") was an Israelite kingdom of the Southern Levant during the Iron Age. C ...

, the southern of the two kingdoms, which was centered in

Judea

Judea or Judaea ( or ; from he, יהודה, Standard ''Yəhūda'', Tiberian ''Yehūḏā''; el, Ἰουδαία, ; la, Iūdaea) is an ancient, historic, Biblical Hebrew, contemporaneous Latin, and the modern-day name of the mountainous so ...

with its capital in

Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

. The Kingdom of Judah was conquered by

Nebuchadnezzar II

Nebuchadnezzar II (Babylonian cuneiform: ''Nabû-kudurri-uṣur'', meaning "Nabu, watch over my heir"; Biblical Hebrew: ''Nəḇūḵaḏneʾṣṣar''), also spelled Nebuchadrezzar II, was the second king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling ...

of the

Neo-Babylonian Empire

The Neo-Babylonian Empire or Second Babylonian Empire, historically known as the Chaldean Empire, was the last polity ruled by monarchs native to Mesopotamia. Beginning with the coronation of Nabopolassar as the King of Babylon in 626 BC and bei ...

in 586 BCE. The Babylonians

destroyed Jerusalem and the

First Temple

Solomon's Temple, also known as the First Temple (, , ), was the Temple in Jerusalem between the 10th century BC and . According to the Hebrew Bible, it was commissioned by Solomon in the United Kingdom of Israel before being inherited by th ...

, which was at the center of ancient Judean worship. The Judeans were subsequently

exiled to Babylon, in what is regarded as the first

Jewish diaspora

The Jewish diaspora ( he, תְּפוּצָה, təfūṣā) or exile (Hebrew: ; Yiddish: ) is the dispersion of Israelites or Jews out of their ancient ancestral homeland (the Land of Israel) and their subsequent settlement in other parts of th ...

.

Seventy years later, after the

conquest of Babylon by the

Persian Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was the largest empire the world had ...

,

Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia (; peo, 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 ), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, the first Persian empire. Schmitt Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Under his rule, the empire embraced ...

allowed the Jews to return to

Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

and

rebuild the Temple. This event came to be known as the

Return to Zion

The return to Zion ( he, שִׁיבָת צִיּוֹן or שבי ציון, , ) is an event recorded in Ezra–Nehemiah of the Hebrew Bible, in which the Jews of the Kingdom of Judah—subjugated by the Neo-Babylonian Empire—were freed from the ...

. Under Persian rule, Judah became

a self-governing Jewish province. After centuries of Persian and

Hellenistic rule, the Jews regained their independence in the

Maccabean Revolt

The Maccabean Revolt ( he, מרד החשמונאים) was a Jewish rebellion led by the Maccabees against the Seleucid Empire and against Hellenistic influence on Jewish life. The main phase of the revolt lasted from 167–160 BCE and ende ...

against the

Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the ...

, which led to the establishment of the

Hasmonean Kingdom

The Hasmonean dynasty (; he, ''Ḥašmōnaʾīm'') was a ruling dynasty of Judea and surrounding regions during classical antiquity, from BCE to 37 BCE. Between and BCE the dynasty ruled Judea semi-autonomously in the Seleucid Empire, and ...

in Judea. It later expanded over much of modern Israel, and into some parts of Jordan and Lebanon. The Hasmonean Kingdom became a client state of the

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

in 63 BCE, and in 6 CE, was incorporated into the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

as the

province of Judaea.

During the

Great Jewish Revolt (66–73 CE), the Romans

destroyed Jerusalem and burned the Second Temple. Of the 600,000 (Tacitus) or 1,000,000 (Josephus) Jews of Jerusalem, all of them either died of starvation, were killed or were sold into slavery. The

Bar Kokhba Revolt

The Bar Kokhba revolt ( he, , links=yes, ''Mereḏ Bar Kōḵḇāʾ''), or the 'Jewish Expedition' as the Romans named it ( la, Expeditio Judaica), was a rebellion by the Jews of the Roman province of Judea, led by Simon bar Kokhba, ag ...

(132–136 CE) led to the destruction of large parts of Judea, and many Jews were killed, exiled, or sold into slavery. The province of Judaea was renamed ''Syria Palaestina.'' These actions are seen by many scholars as an attempt to disconnect the Jewish people from their homeland.''

[H.H. Ben-Sasson, ''A History of the Jewish People'', Harvard University Press, 1976, , page 334: "In an effort to wipe out all memory of the bond between the Jews and the land, Hadrian changed the name of the province from Iudaea to Syria-Palestina, a name that became common in non-Jewish literature."]'' In the following centuries, many Jews emigrated to thriving centers in the

diaspora

A diaspora ( ) is a population that is scattered across regions which are separate from its geographic place of origin. Historically, the word was used first in reference to the dispersion of Greeks in the Hellenic world, and later Jews after ...

. Others continued living in the region, especially in the

Galilee

Galilee (; he, הַגָּלִיל, hagGālīl; ar, الجليل, al-jalīl) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Galilee traditionally refers to the mountainous part, divided into Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and Lower Gali ...

, the

coastal plain

A coastal plain is flat, low-lying land adjacent to a sea coast. A fall line commonly marks the border between a coastal plain and a piedmont area. Some of the largest coastal plains are in Alaska and the southeastern United States. The Gulf Co ...

, and on the edges of Judea, and some converted.

[David Goodblatt, 'The political and social history of the Jewish community in the Land of Israel,' in William David Davies, Louis Finkelstein, Steven T. Katz (eds.) ''The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 4, The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period'', Cambridge University Press, 2006 pp.404-430, p.406.] By the fourth century CE, the Jews, who had previously constituted the majority of Palestine, had become a minority.

A small presence of Jews has been attested for almost all of the period. For example, according to tradition, the Jewish community of

Peki'in

Peki'in (alternatively Peqi'in) ( he, פְּקִיעִין) or Buqei'a ( ar, البقيعة), is a Druze–Arab town with local council status in Israel's Northern District. It is located eight kilometres east of Ma'alot-Tarshiha in the Uppe ...

has maintained a Jewish presence since the

Second Temple period

The Second Temple period in Jewish history lasted approximately 600 years (516 BCE - 70 CE), during which the Second Temple existed. It started with the return to Zion and the construction of the Second Temple, while it ended with the First Je ...

.'

Jewish religious belief

Jewish religious belief holds that the

Land of Israel

The Land of Israel () is the traditional Jewish name for an area of the Southern Levant. Related biblical, religious and historical English terms include the Land of Canaan, the Promised Land, the Holy Land, and Palestine (see also Isr ...

is a God-given inheritance of the

Children of Israel

The Israelites (; , , ) were a group of Semitic-speaking tribes in the ancient Near East who, during the Iron Age, inhabited a part of Canaan.

The earliest recorded evidence of a people by the name of Israel appears in the Merneptah Stele o ...

based on the

Torah

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the ...

, particularly the books of

Genesis

Genesis may refer to:

Bible

* Book of Genesis, the first book of the biblical scriptures of both Judaism and Christianity, describing the creation of the Earth and of mankind

* Genesis creation narrative, the first several chapters of the Book of ...

and

Exodus

Exodus or the Exodus may refer to:

Religion

* Book of Exodus, second book of the Hebrew Torah and the Christian Bible

* The Exodus, the biblical story of the migration of the ancient Israelites from Egypt into Canaan

Historical events

* E ...

, as well as on the later

Prophets

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the s ...

. According to the Book of Genesis,

Canaan

Canaan (; Phoenician: 𐤊𐤍𐤏𐤍 – ; he, כְּנַעַן – , in pausa – ; grc-bib, Χανααν – ;The current scholarly edition of the Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus T ...

was first

promised to

Abraham

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the special relationship between the Je ...

's descendants; the text is explicit that this is a

covenant

Covenant may refer to:

Religion

* Covenant (religion), a formal alliance or agreement made by God with a religious community or with humanity in general

** Covenant (biblical), in the Hebrew Bible

** Covenant in Mormonism, a sacred agreement b ...

between

God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

and Abraham for his descendants. The belief that God had assigned Canaan to the Israelites as a Promised Land is also conserved also in Christian and Islamic traditions.

Among Jews in the Diaspora, the Land of Israel was revered in a cultural, national, ethnic, historical, and religious sense. They thought of a return to it in a future

messianic age

In Abrahamic religions, the Messianic Age is the future period of time on Earth in which the messiah will reign and bring universal peace and brotherhood, without any evil. Many believe that there will be such an age; some refer to it as the cons ...

. Return to Zion remained a recurring theme among generations, particularly in

Passover

Passover, also called Pesach (; ), is a major Jewish holiday that celebrates the Biblical story of the Israelites escape from slavery in Egypt, which occurs on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nisan, the first month of Aviv, or spring. ...

and

Yom Kippur

Yom Kippur (; he, יוֹם כִּפּוּר, , , ) is the holiest day in Judaism and Samaritanism. It occurs annually on the 10th of Tishrei, the first month of the Hebrew calendar. Primarily centered on atonement and repentance, the day' ...

prayers, which traditionally concluded with "

Next year in Jerusalem

''L'Shana Haba'ah B'Yerushalayim'' ( he, לשנה הבאה בירושלים), lit. "Next year in Jerusalem", is a phrase that is often sung at the end of the Passover Seder_and_at_the_end_of_the_'' isan_in_the__Hebrew_..._and_at_the_end_of_the_' ...

", and in the thrice-daily

Amidah

The ''Amidah Amuhduh'' ( he, תפילת העמידה, ''Tefilat HaAmidah'', 'The Standing Prayer'), also called the ''Shemoneh Esreh'' ( 'eighteen'), is the central prayer of the Jewish liturgy. Observant Jews recite the ''Amidah'' at each ...

(Standing prayer). The biblical prophecy of

''Kibbutz Galuyot'', the ingathering of exiles in the Land of Israel as foretold by the

Prophets

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the s ...

, became a central idea in Zionism.

Pre-Zionist initiatives

In the middle of the 16th century, the Portuguese Sephardi

Joseph Nasi

Joseph Nasi (1524, Portugal – 1579, Konstantiniyye), known in Portuguese as João Miques, was a Portuguese Sephardi diplomat and administrator, member of the House of Mendes/Benveniste, nephew of Dona Gracia Mendes Nasi, and an influential fi ...

, with the support of the Ottoman Empire, tried to gather the Portuguese Jews, first to migrate to

Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

, then owned by the Republic of Venice, and later to resettle in Tiberias. Nasi – who never converted to Islam

[Marc David Baer]

''Honored by the Glory of Islam: Conversion and Conquest in Ottoman Europe,'

Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print book ...

2011 p.137:'Hatice Turhan’s insistence on conversion mitigated any educational edge Jewish physicians had over others. In contrast to the mid-sixteenth century, when Jews such as Joseph Nasi rose to the highest medical post in the empire and played an active role at the Ottoman court while remaining practicing Jews, and even convinced Suleiman to intervene with the pope on behalf of Portuguese Jews who were Ottoman subjects imprisoned in Ancona, the leading physicians at court in the mid-to late seventeenth century such as Hayatizade and Nuh Efendi had to be converted Jews.’ eventually obtained the highest medical position in the empire, and actively participated in court life. He convinced Suleiman I to intervene with the Pope on behalf of Ottoman-subject Portuguese Jews imprisoned in Ancona.

[ Between the 4th and 19th centuries, Nasi's was the only practical attempt to establish some sort of Jewish political center in Palestine.

In the 17th century ]Sabbatai Zevi

Sabbatai Zevi (; August 1, 1626 – c. September 17, 1676), also spelled Shabbetai Ẓevi, Shabbeṯāy Ṣeḇī, Shabsai Tzvi, Sabbatai Zvi, and ''Sabetay Sevi'' in Turkish, was a Jewish mystic and ordained rabbi from Smyrna (now İzmir, Turk ...

(1626–1676) announced himself as the Messiah and gained many Jews to his side, forming a base in Salonika. He first tried to establish a settlement in Gaza, but moved later to Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to prom ...

. After deposing the old rabbi Aaron Lapapa in the spring of 1666, the Jewish community of Avignon

Avignon (, ; ; oc, Avinhon, label= Provençal or , ; la, Avenio) is the prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of Southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the commune had ...

, France prepared to emigrate to the new kingdom. The readiness of the Jews of the time to believe the messianic claims of Sabbatai Zevi may be largely explained by the desperate state of Central European Jewry in the mid-17th century. The bloody pogroms of Bohdan Khmelnytsky

Bohdan Zynovii Mykhailovych Khmelnytskyi ( Ruthenian: Ѕѣнові Богданъ Хмелнiцкiи; modern ua, Богдан Зиновій Михайлович Хмельницький; 6 August 1657) was a Ukrainian military commander and ...

had wiped out one-third of the Jewish population and destroyed many centers of Jewish learning and communal life.

In the early 19th century, a group of Jews known as the ''perushim

The ''perushim'' ( he, פרושים) were Jewish disciples of the Vilna Gaon, Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, who left Lithuania at the beginning of the 19th century to settle in the Land of Israel, which was then part of Ottoman Syria under Ott ...

'' left Lithuania to settle in Ottoman Palestine.

Establishment of the Zionist movement

In the 19th century, a current in Judaism supporting a return to Zion

The return to Zion ( he, שִׁיבָת צִיּוֹן or שבי ציון, , ) is an event recorded in Ezra–Nehemiah of the Hebrew Bible, in which the Jews of the Kingdom of Judah—subjugated by the Neo-Babylonian Empire—were freed from the ...

grew in popularity, particularly in Europe, where antisemitism and hostility toward Jews were growing. The idea of returning to Palestine was rejected by the conferences of rabbis held in that epoch. Individual efforts supported the emigration of groups of Jews to Palestine, pre-Zionist Aliyah, even before 1897

Events

January–March

* January 2 – The International Alpha Omicron Pi sorority is founded, in New York City.

* January 4 – A British force is ambushed by Chief Ologbosere, son-in-law of the ruler. This leads to a puni ...

, the year considered as the start of practical Zionism.

The Reformed Jews rejected this idea of a return to Zion. The conference of rabbis, at Frankfurt am Main

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , " Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on it ...

, July 15–28, 1845, deleted from the ritual all prayers for a return to Zion and a restoration of a Jewish state. The Philadelphia Conference, 1869, followed the lead of the German rabbis and decreed that the Messianic hope of Israel is "the union of all the children of God in the confession of the unity of God". The Pittsburgh Conference, 1885, reiterated this Messianic idea of reformed Judaism, expressing in a resolution that "we consider ourselves no longer a nation, but a religious community; and we therefore expect neither a return to Palestine, nor a sacrificial worship under the sons of Aaron, nor the restoration of any of the laws concerning a Jewish state".Jewish settlements were proposed for establishment in the upper Mississippi region by W.D. Robinson in 1819. Others were developed near Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

in 1850, by the American Consul Warder Cresson

Warder Cresson (July 13, 1798 – November 6, 1860), later known as Michael Boaz Israel ben Abraham (), was an American diplomat. He was appointed the first U.S. Consul to Jerusalem in 1844.

Biography

Warder Cresson was born in Philadelphia, Pe ...

, a convert to Judaism. Cresson was tried and condemned for lunacy in a suit filed by his wife and son. They asserted that only a lunatic would convert to Judaism from Christianity. After a second trial, based on the centrality of American 'freedom of faith' issues and antisemitism, Cresson won the bitterly contested suit. He emigrated to Ottoman Palestine and established an agricultural colony in the Valley of Rephaim The Valley of Rephaim ( he, עמק רפאים, ''Emeq Rephaim'') (; , R.V.) or Valley of the Rephaim,Jerusalem Bible (1966) adds "the": 1 Chronicles 14:9 is a valley descending southwest from Jerusalem to Nahal Sorek below, it is an ancient route f ...

of Jerusalem. He hoped to "prevent any attempts being made to take advantage of the necessities of our poor brethren ... (that would) ... FORCE them into a pretended conversion."

Moral but not practical efforts were made in Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

to organize a Jewish emigration, by Abraham Benisch

Abraham Benisch (; 1811 – 31 July 1878, London) was an English Hebraist, editor, and journalist. He wrote numerous works in the domain of Judaism, Biblical studies, biography, and travel, and during a period of nearly forty years contributed we ...

and Moritz Steinschneider

Moritz Steinschneider (30 March 1816, Prostějov, Moravia, Austrian Empire – 24 January 1907, Berlin) was a Moravian bibliographer and Orientalist. He received his early instruction in Hebrew from his father, Jacob Steinschneider ( 1782; ...

in 1835. In the United States, Mordecai Noah

Mordecai Manuel Noah (July 14, 1785, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – May 22, 1851, New York) was an American sheriff, playwright, diplomat, journalist, and utopian. He was born in a family of Portuguese Sephardic ancestry. He was the most importa ...

attempted to establish a Jewish refuge opposite Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second-largest city in the U.S. state of New York (behind only New York City) and the seat of Erie County. It is at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of the Niagara River, and is across the Canadian border from Sou ...

, on Grand Isle, 1825. These early Jewish nation building efforts of Cresson, Benisch, Steinschneider and Noah failed.

Sir Moses Montefiore

Sir Moses Haim Montefiore, 1st Baronet, (24 October 1784 – 28 July 1885) was a British financier and banker, activist, philanthropist and Sheriff of London. Born to an Italian Sephardic Jewish family based in London, aft ...

, famous for his intervention in favor of Jews around the world, including the attempt to rescue Edgardo Mortara

The Mortara case ( it, caso Mortara, links=no) was an Italian ''cause célèbre'' that captured the attention of much of Europe and North America in the 1850s and 1860s. It concerned the Papal States' seizure of a six-year-old boy named Edgardo ...

, established a colony for Jews in Palestine. In 1854, his friend Judah Touro

Judah Touro (June 16, 1775 – January 18, 1854) was an American businessman and philanthropist.

Early life and career

Touro's father Isaac Touro of Holland was chosen as the hazzan at the Touro Synagogue in 1762, a Portuguese Sephardic cong ...

bequeathed money to fund Jewish residential settlement in Palestine. Montefiore was appointed executor of his will, and used the funds for a variety of projects, including building in 1860 the first Jewish residential settlement and almshouse outside of the old walled city of Jerusalem—today known as ''Mishkenot Sha'ananim

, settlement_type = Neighborhood of Jerusalem

, image_skyline = שכונת משכנות שאננים וטחנת הרוח. צולם מכיוון העיר העתיקה.jpg

, imagesize = 300px

, image_caption = View of Mishkenot ...

.'' Laurence Oliphant failed in a like attempt to bring to Palestine the Jewish proletariat of Poland, Lithuania, Romania, and the Turkish Empire (1879 and 1882).

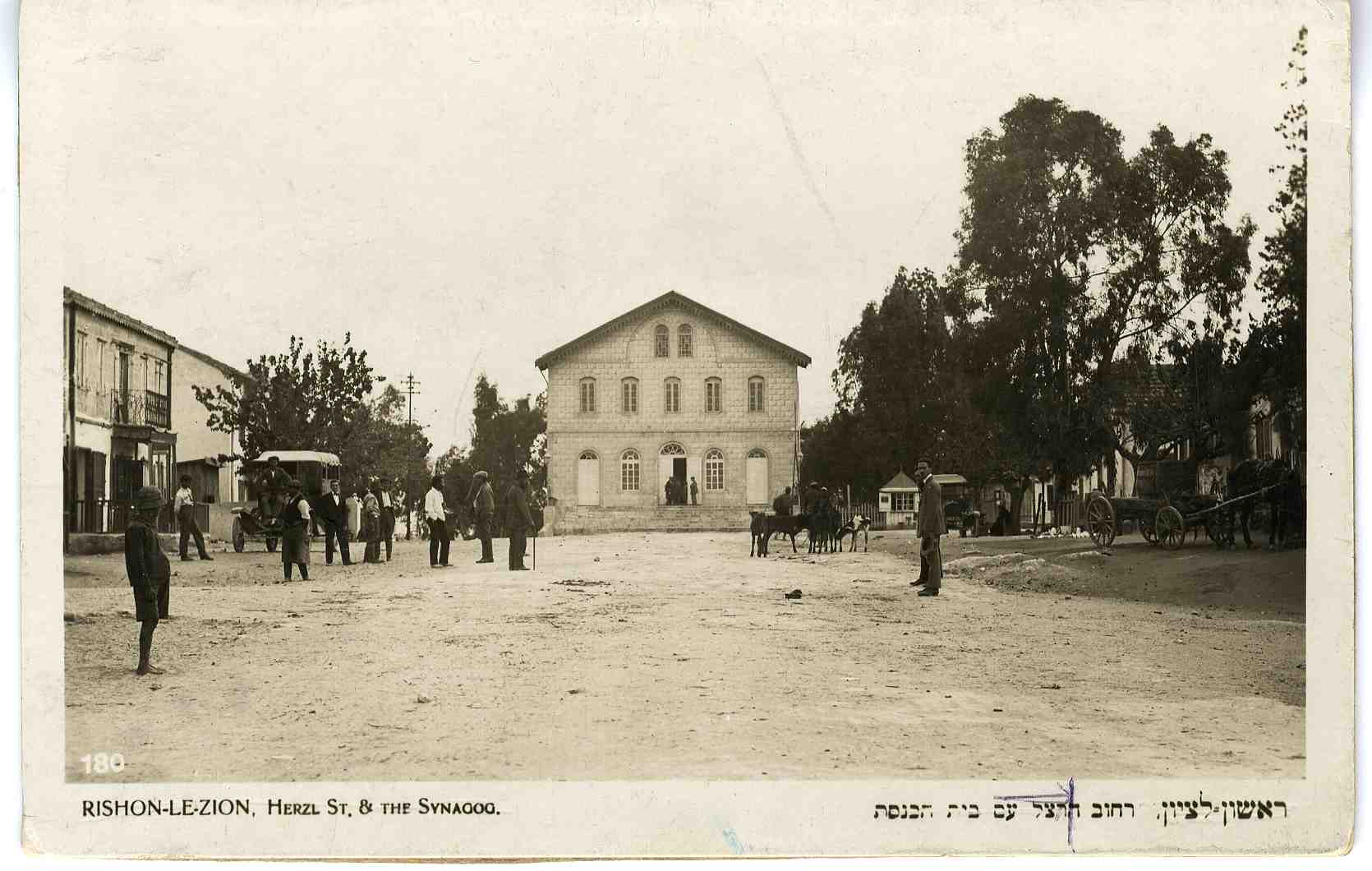

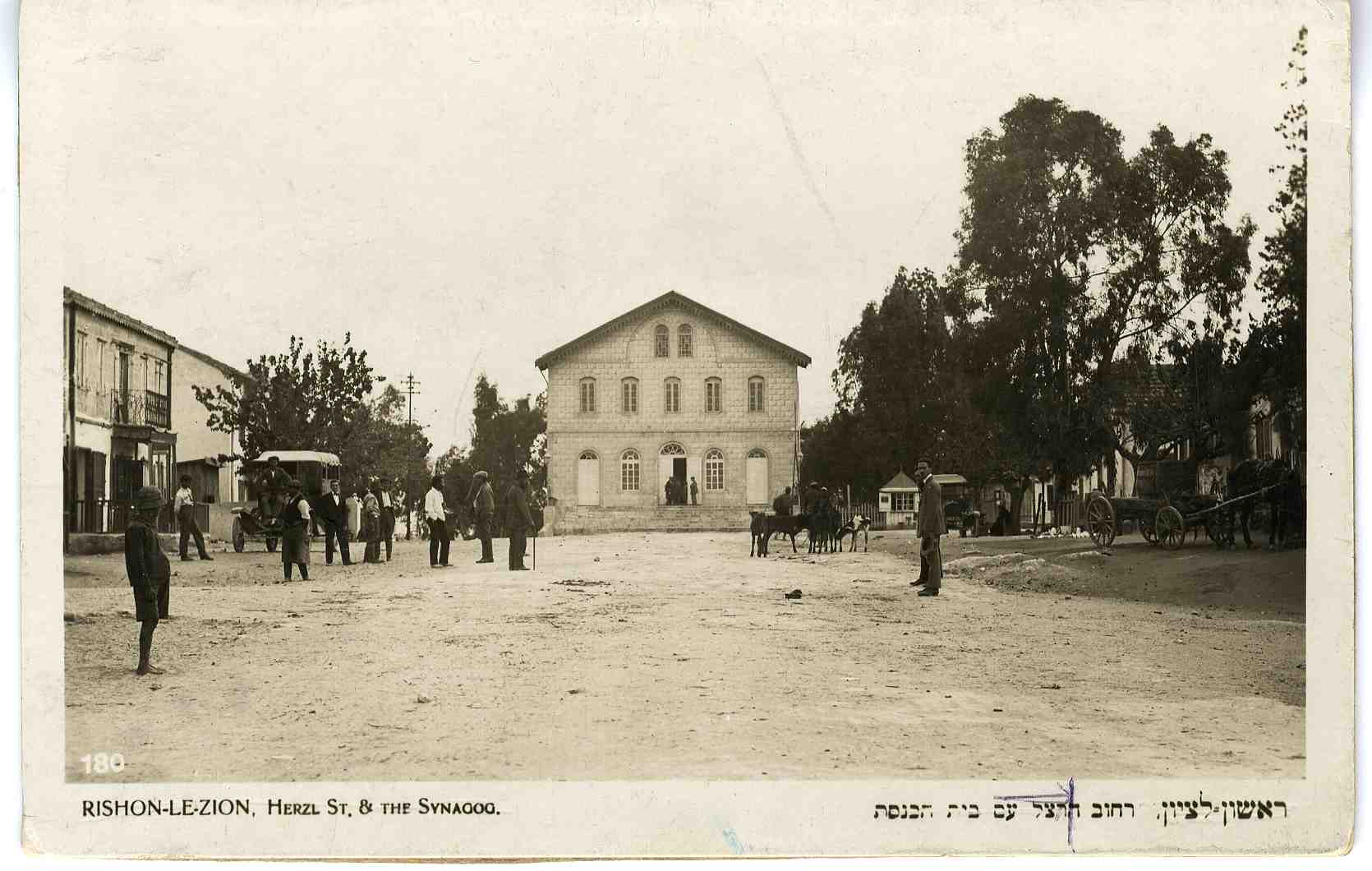

The official beginning of the construction of the New Yishuv

Yishuv ( he, ישוב, literally "settlement"), Ha-Yishuv ( he, הישוב, ''the Yishuv''), or Ha-Yishuv Ha-Ivri ( he, הישוב העברי, ''the Hebrew Yishuv''), is the body of Jewish residents in the Land of Israel (corresponding to the s ...

in Palestine is usually dated to the arrival of the Bilu

Bilu may refer to:

People

* Bilú (footballer, 1900-1965), Virgílio Pinto de Oliveira, Brazilian football manager and former centre-back

* Asher Bilu (born 1936), Australian artist

* Bilú (footballer, born 1974), Luciano Lopes de Souza, Brazi ...

group in 1882, who commenced the First Aliyah

The First Aliyah (Hebrew: העלייה הראשונה, ''HaAliyah HaRishona''), also known as the agriculture Aliyah, was a major wave of Jewish immigration (''aliyah'') to Ottoman Syria between 1881 and 1903. Jews who migrated in this wave came ...

. In the following years, Jewish immigration to Palestine started in earnest. Most immigrants came from the Russian Empire, escaping the frequent pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russian ...

s and state-led persecution in what are now Ukraine and Poland. They founded a number of agricultural settlements with financial support from Jewish philanthropists in Western Europe. Additional Aliyahs followed the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

and its eruption of violent pogroms. At the end of the 19th century, Jews were a small minority in Palestine.

In the 1890s,

In the 1890s, Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl; hu, Herzl Tivadar; Hebrew name given at his brit milah: Binyamin Ze'ev (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austro-Hungarian Jewish lawyer, journalist, playwright, political activist, and writer who was the father of modern po ...

(the father of political Zionism) infused Zionism with a new ideology and practical urgency, leading to the First Zionist Congress

The First Zionist Congress ( he, הקונגרס הציוני הראשון) was the inaugural congress of the Zionist Organization (ZO) held in Basel (Basle), from August 29 to August 31, 1897. 208 delegates and 26 press correspondents attende ...

at Basel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (B ...

in 1897, which created the World Zionist Organization (WZO). Herzl's aim was to initiate necessary preparatory steps for the development of a Jewish state. Herzl's attempts to reach a political agreement with the Ottoman rulers of Palestine were unsuccessful and he sought the support of other governments. The World Zionist Organization

The World Zionist Organization ( he, הַהִסְתַּדְּרוּת הַצִּיּוֹנִית הָעוֹלָמִית; ''HaHistadrut HaTzionit Ha'Olamit''), or WZO, is a non-governmental organization that promotes Zionism. It was founded as the ...

supported small-scale settlement in Palestine; it focused on strengthening Jewish feeling and consciousness and on building a worldwide federation.

The

The Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

, with its long record of anti-Jewish pogroms

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russian ...

, was widely regarded as the historic enemy of the Jewish people. The Zionist movement's headquarters were located in Berlin, as many of its leaders were German Jews who spoke German.

Organization

Zionism developed from Proto-Zionist initiatives and movements, such as Hovevei Zion. It coalesced and became organized in the form of the Zionist Congress, which created nation-building institutions and acted in Ottoman and British Palestine as well as internationally.

=Pre-state institutions

=

* Zionist Organization (ZO), est. 1897

**Zionist Congress

The Zionist Congress was established in 1897 by Theodor Herzl as the supreme organ of the Zionist Organization (ZO) and its legislative authority. In 1960 the names were changed to World Zionist Congress ( he, הקונגרס הציוני העו ...

(est. 1897), the supreme organ of the ZO

**Palestine Office

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

(est. 1908), the executive arm of the ZO in Palestine

**Jewish National Fund

Jewish National Fund ( he, קֶרֶן קַיֶּימֶת לְיִשְׂרָאֵל, ''Keren Kayemet LeYisrael'', previously , ''Ha Fund HaLeumi'') was founded in 1901 to buy and develop land in Ottoman Syria (later Mandatory Palestine, and subsequ ...

(JNF), est. 1901 to buy and develop land in Palestine

**Keren Hayesod

Keren Hayesod – United Israel Appeal ( he, קרן היסוד, literally "The Foundation Fund") is an official fundraising organization for Israel with branches in 45 countries. Its work is carried out in accordance with the Keren haYesod Law-5 ...

, est. 1920 to collect funds

**Jewish Agency

The Jewish Agency for Israel ( he, הסוכנות היהודית לארץ ישראל, translit=HaSochnut HaYehudit L'Eretz Yisra'el) formerly known as The Jewish Agency for Palestine, is the largest Jewish non-profit organization in the world. ...

, est. 1929 as the worldwide operative branch of the ZO

=Funding

=

The Zionist enterprise was mainly funded by major benefactors who made large contributions, sympathisers from Jewish communities across the world (see for instance the Jewish National Fund's collection boxes), and the settlers themselves. The movement established a bank for administering its finances, the Jewish Colonial Trust (est. 1888, incorporated in London in 1899). A local subsidiary was formed in 1902 in Palestine, the Anglo-Palestine Bank

Bank Leumi ( he, בנק לאומי, lit. ''National Bank''; ar, بنك لئومي) is an Israeli bank. It was founded on February 27, 1902, in Jaffa as the ''Anglo Palestine Company'' as subsidiary of the Jewish Colonial Trust (Jüdische Kolonia ...

.

A list of pre-state large contributors to Pre-Zionist and Zionist enterprises would include, alphabetically,

*Isaac Leib Goldberg

Isaac Leib Goldberg ( he, יצחק לייב גולדברג, 7 February 1860 – 14 September 1935) was a Zionist leader and philanthropist in both Ottoman Palestine and the Russian Empire, and one of the principal founders of Rishon LeZion, the ...

(1860–1935), Zionist leader and philanthropist from Russia

*Maurice de Hirsch

Moritz Freiherr von Hirsch auf Gereuth (german: Moritz Freiherr von Hirsch auf Gereuth; french: Maurice, baron de Hirsch de Gereuth; 9 December 1831 – 21 April 1896), commonly known as Maurice de Hirsch, was a German Jewish financier and phila ...

(1831–1896), German Jewish financier and philanthropist, founder of the Jewish Colonization Association

*Moses Montefiore

Sir Moses Haim Montefiore, 1st Baronet, (24 October 1784 – 28 July 1885) was a British financier and banker, activist, philanthropist and Sheriff of London. Born to an Italian Sephardic Jewish family based in London, aft ...

(1784–1885), British Jewish banker and philanthropist in Britain and the Levant, initiator and financier of Proto-Zionism

*Edmond James de Rothschild

Baron Abraham Edmond Benjamin James de Rothschild (Hebrew: הברון אברהם אדמונד בנימין ג'יימס רוטשילד - ''HaBaron Avraham Edmond Binyamin Ya'akov Rotshield''; 19 August 1845 – 2 November 1934) was a French memb ...

(1845–1934), French Jewish banker and major donor of the Zionist project

=Pre-state self-defense

=

A list of Jewish pre-state self-defense organisations in Palestine would include

* Bar-Giora (organization) (1907-1909)

* HaMagen, "The Shield" (1915–17)[Hemmingby, Cato]

''Conflict and Military Terminology: The Language of the Israel Defense Forces''

Master's thesis, University of Oslo, 2011. Accessed January 8, 2021.

* HaNoter, "The Guard" (pre-WWI, distinct from the British Madate-period Notrim)[

* Hashomer (1909-1920)

*]Haganah

Haganah ( he, הַהֲגָנָה, lit. ''The Defence'') was the main Zionist paramilitary organization of the Jewish population ("Yishuv") in Mandatory Palestine between 1920 and its disestablishment in 1948, when it became the core of the I ...

(1920-1948)

**Palmach

The Palmach (Hebrew: , acronym for , ''Plugot Maḥatz'', "Strike Companies") was the elite fighting force of the Haganah, the underground army of the Yishuv (Jewish community) during the period of the British Mandate for Palestine. The Palmach ...

(1941-1948)

Territories considered

Throughout the first decade of the Zionist movement, there were several instances where some Zionist figures supported a Jewish state in places outside Palestine, such as Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa. The country is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the south by Tanzania. The ...

and Argentina.Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl; hu, Herzl Tivadar; Hebrew name given at his brit milah: Binyamin Ze'ev (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austro-Hungarian Jewish lawyer, journalist, playwright, political activist, and writer who was the father of modern po ...

, the founder of political Zionism was initially content with any Jewish self-governed state.Maurice de Hirsch

Moritz Freiherr von Hirsch auf Gereuth (german: Moritz Freiherr von Hirsch auf Gereuth; french: Maurice, baron de Hirsch de Gereuth; 9 December 1831 – 21 April 1896), commonly known as Maurice de Hirsch, was a German Jewish financier and phila ...

. It is unclear if Herzl seriously considered this alternative plan, however he later reaffirmed that Palestine would have greater attraction because of the historic ties of Jews with that area.Zion

Zion ( he, צִיּוֹן ''Ṣīyyōn'', LXX , also variously Romanization of Hebrew, transliterated ''Sion'', ''Tzion'', ''Tsion'', ''Tsiyyon'') is a placename in the Hebrew Bible used as a synonym for Jerusalem as well as for the Land of Isra ...

became the name of the movement, after the place where King David established his kingdom, following his conquest of the Jebusite fortress there (II Samuel 5:7, I Kings 8:1). The name Zion was synonymous with Jerusalem. Palestine only became Herzl's main focus after his Zionist manifesto 'Der Judenstaat

''Der Judenstaat'' (German, literally ''The State of the Jews'', commonly rendered as ''The Jewish State'') is a pamphlet written by Theodor Herzl and published in February 1896 in Leipzig and Vienna by M. Breitenstein's Verlags-Buchhandlung. It ...

' was published in 1896, but even then he was hesitant to focus efforts solely on resettlement in Palestine when speed was of the essence.Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually served as a leading imperialist in coalition with the C ...

offered Herzl in the Uganda Protectorate

The Protectorate of Uganda was a protectorate of the British Empire from 1894 to 1962. In 1893 the Imperial British East Africa Company transferred its administration rights of territory consisting mainly of the Kingdom of Buganda to the Bri ...

for Jewish settlement in Great Britain's East African colonies.World Zionist Organization

The World Zionist Organization ( he, הַהִסְתַּדְּרוּת הַצִּיּוֹנִית הָעוֹלָמִית; ''HaHistadrut HaTzionit Ha'Olamit''), or WZO, is a non-governmental organization that promotes Zionism. It was founded as the ...

's Congress at its sixth meeting, where a fierce debate ensued. Some groups felt that accepting the scheme would make it more difficult to establish a Jewish state in Palestine, the African land was described as an " ante-chamber to the Holy Land". It was decided to send a commission to investigate the proposed land by 295 to 177 votes, with 132 abstaining. The following year, Congress sent a delegation to inspect the plateau. A temperate climate due to its high elevation, was thought to be suitable for European settlement. However, the area was populated by a large number of Maasai, who did not seem to favour an influx of Europeans. Furthermore, the delegation found it to be filled with lion

The lion (''Panthera leo'') is a large cat of the genus '' Panthera'' native to Africa and India. It has a muscular, broad-chested body; short, rounded head; round ears; and a hairy tuft at the end of its tail. It is sexually dimorphic; adu ...

s and other animals.

After Herzl died in 1904, the Congress decided on the fourth day of its seventh session in July 1905 to decline the British offer and, according to Adam Rovner, "direct all future settlement efforts solely to Palestine".Israel Zangwill

Israel Zangwill (21 January 18641 August 1926) was a British author at the forefront of cultural Zionism during the 19th century, and was a close associate of Theodor Herzl. He later rejected the search for a Jewish homeland in Palestine and be ...

's Jewish Territorialist Organization

The Jewish Territorial Organisation, known as the ITO, was a Jewish political movement which first arose in 1903 in response to the British Uganda Offer, but which was institutionalized in 1905. Its main goal was to find an alternative territory ...

aimed for a Jewish state anywhere, having been established in 1903 in response to the Uganda Scheme. It was supported by a number of the Congress's delegates. Following the vote, which had been proposed by Max Nordau

Max Simon Nordau (born ''Simon Maximilian Südfeld''; 29 July 1849 – 23 January 1923) was a Zionist leader, physician, author, and social critic.

He was a co-founder of the Zionist Organization together with Theodor Herzl, and president or vic ...

, Zangwill charged Nordau that he "will be charged before the bar of history," and his supporters blamed the Russian voting bloc of Menachem Ussishkin

Menachem Ussishkin (russian: Авраам Менахем Мендл Усышкин ''Avraham Menachem Mendel Ussishkin'', he, מנחם אוסישקין) (August 14, 1863 – October 2, 1941) was a Russian-born Zionist leader and head of the Je ...

for the outcome of the vote.Zionist Socialist Workers Party

Zionist-Socialist Workers Party (russian: Сионистско-социалистическая рабочая партия), often referred to simply as Zionist-Socialists or S.S. by their Russian initials, was a Jewish territorialist and social ...

was also an organization that favored the idea of a Jewish territorial autonomy outside of Palestine.[Ėstraĭkh, G. ''In Harness: Yiddish Writers' Romance with Communism. Judaic traditions in literature, music, and art.'' ]Syracuse, New York

Syracuse ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Onondaga County, New York, United States. It is the fifth-most populous city in the state of New York following New York City, Buffalo, Yonkers, and Rochester.

At the 2020 census, the city' ...

: Syracuse University Press, 2005. p. 30

As an alternative to Zionism, Soviet authorities established a Jewish Autonomous Oblast

The Jewish Autonomous Oblast (JAO; russian: Евре́йская автоно́мная о́бласть, (ЕАО); yi, ייִדישע אװטאָנאָמע געגנט, ; )In standard Yiddish: , ''Yidishe Oytonome Gegnt'' is a federal subject ...

in 1934, which remains extant as the only autonomous oblast of Russia.

Balfour Declaration and the Mandate for Palestine

Lobbying by Russian Jewish immigrant

Lobbying by Russian Jewish immigrant Chaim Weizmann

Chaim Azriel Weizmann ( he, חיים עזריאל ויצמן ', russian: Хаим Евзорович Вейцман, ''Khaim Evzorovich Veytsman''; 27 November 1874 – 9 November 1952) was a Russian-born biochemist, Zionist leader and Israel ...

, together with fear that American Jews

American Jews or Jewish Americans are American citizens who are Jewish, whether by religion, ethnicity, culture, or nationality. Today the Jewish community in the United States consists primarily of Ashkenazi Jews, who descend from diaspora J ...

would encourage the US to support Germany in the war against Russia, culminated in the British government's Balfour Declaration

The Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British government in 1917 during the First World War announcing its support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then an Ottoman regio ...

of 1917.

It endorsed the creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, as follows:

In 1922, the

In 1922, the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

adopted the declaration, and granted to Britain the Palestine Mandate:

Weizmann's role in obtaining the Balfour Declaration led to his election as the Zionist movement's leader. He remained in that role until 1948, and then was elected as the first President of Israel after the nation gained independence.

A number of high-level representatives of the international Jewish women's community participated in the First World Congress of Jewish Women, which was held in Vienna, Austria, in May 1923. One of the main resolutions was: "It appears ... to be the duty of all Jews to co-operate in the social-economic reconstruction of Palestine and to assist in the settlement of Jews in that country."

Rise of Nazism and the Holocaust

In 1933, Hitler came to power in Germany, and in 1935 the Nuremberg Laws made German Jews (and later Anschluss, Austrian and Czech Jews) stateless refugees. Similar rules were applied by the many Axis powers, Nazi allies in Europe. The subsequent growth in Jewish migration and the impact of Nazi propaganda aimed at the Arab world fostered to the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine. Britain established the Peel Commission to investigate the situation. The commission called for a two-state solution and compulsory Population transfer, transfer of populations. The Arabs opposed the partition plan and Britain later rejected this solution and instead implemented the White Paper of 1939. This planned to end Jewish immigration by 1944 and to allow no more than 75,000 additional Jewish migrants. At the end of the five-year period in 1944, only 51,000 of the 75,000 immigration certificates provided for had been utilized, and the British offered to allow immigration to continue beyond cutoff date of 1944, at a rate of 1500 per month, until the remaining quota was filled.[Study (June 30, 1978)]

The Origins and Evolution of the Palestine Problem Part I: 1917-1947 - Study (30 June 1978)

, access-date: November 10, 2018 According to Arieh Kochavi, at the end of the war, the Mandatory Government had 10,938 certificates remaining and gives more details about government policy at the time. During

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, as the horrors of the Holocaust became known, the Zionist leadership formulated the One Million Plan, a reduction from Ben-Gurion's previous target of two million immigrants. Following the end of the war, many Sh'erit ha-Pletah, stateless refugees, mainly Holocaust survivors, began Aliyah Bet, migrating to Palestine in small boats in defiance of British rules. The Holocaust united much of the rest of world Jewry behind the Zionist project.

Post-World War II

With the Operation Barbarossa, German invasion of the USSR in 1941, Stalin reversed his long-standing opposition to Zionism, and tried to mobilize worldwide Jewish support for the Soviet war effort. A Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee was set up in Moscow. Many thousands of Jewish refugees fled the Nazis and entered the Soviet Union during the war, where they reinvigorated Jewish religious activities and opened new synagogues. In May 1947 Soviet Deputy Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko told the United Nations that the USSR supported the partition of Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state. The USSR formally voted that way in the UN in November 1947. However once Israel was established, Stalin reversed positions, favoured the Arabs, arrested the leaders of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, and launched attacks on Jews in the USSR.

In 1947, the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine recommended that western Palestine should be partitioned into a Jewish state, an Arab state and a Corpus separatum (Jerusalem), UN-controlled territory, ''Corpus separatum'', around Jerusalem. This United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine, partition plan was adopted on November 29, 1947, with UN GA Resolution 181, 33 votes in favor, 13 against, and 10 abstentions. The vote led to celebrations in Jewish communities and protests in Arab communities throughout Palestine. Violence throughout the country, previously an 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine, Arab and Jewish insurgency in Mandatory Palestine, Jewish insurgency against the British, Jewish-Arab communal violence, spiralled into the 1947–1949 Palestine war. The conflict led to an 1948 Palestinian exodus, exodus of about 711,000 Palestinian people, Palestinian Arabs, outside of Israel's territories. More than a quarter had already fled prior to the

With the Operation Barbarossa, German invasion of the USSR in 1941, Stalin reversed his long-standing opposition to Zionism, and tried to mobilize worldwide Jewish support for the Soviet war effort. A Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee was set up in Moscow. Many thousands of Jewish refugees fled the Nazis and entered the Soviet Union during the war, where they reinvigorated Jewish religious activities and opened new synagogues. In May 1947 Soviet Deputy Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko told the United Nations that the USSR supported the partition of Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state. The USSR formally voted that way in the UN in November 1947. However once Israel was established, Stalin reversed positions, favoured the Arabs, arrested the leaders of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, and launched attacks on Jews in the USSR.

In 1947, the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine recommended that western Palestine should be partitioned into a Jewish state, an Arab state and a Corpus separatum (Jerusalem), UN-controlled territory, ''Corpus separatum'', around Jerusalem. This United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine, partition plan was adopted on November 29, 1947, with UN GA Resolution 181, 33 votes in favor, 13 against, and 10 abstentions. The vote led to celebrations in Jewish communities and protests in Arab communities throughout Palestine. Violence throughout the country, previously an 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine, Arab and Jewish insurgency in Mandatory Palestine, Jewish insurgency against the British, Jewish-Arab communal violence, spiralled into the 1947–1949 Palestine war. The conflict led to an 1948 Palestinian exodus, exodus of about 711,000 Palestinian people, Palestinian Arabs, outside of Israel's territories. More than a quarter had already fled prior to the Israeli Declaration of Independence

The Israeli Declaration of Independence, formally the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel ( he, הכרזה על הקמת מדינת ישראל), was proclaimed on 14 May 1948 ( 5 Iyar 5708) by David Ben-Gurion, the Executiv ...