Zen ( zh, t=禪, p=Chán; ja, text=

禅, translit=zen; ko, text=선, translit=Seon; vi, text=Thiền) is a

school

A school is an educational institution designed to provide learning spaces and learning environments for the teaching of students under the direction of teachers. Most countries have systems of formal education, which is sometimes co ...

of

Mahayana Buddhism

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing br ...

that originated in

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

during the

Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an Zhou dynasty (690–705), interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dyn ...

, known as the

Chan School (''Chánzong'' 禪宗), and later developed into various sub-schools and branches. From China, Chán spread south to

Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making ...

and became

Vietnamese Thiền

Vietnamese may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Vietnam, a country in Southeast Asia

** A citizen of Vietnam. See Demographics of Vietnam.

* Vietnamese people, or Kinh people, a Southeast Asian ethnic group native to Vietnam

** Overse ...

, northeast to

Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic ...

to become

Seon Buddhism, and east to

Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

, becoming

Japanese Zen

:''See also Zen for an overview of Zen, Chan Buddhism for the Chinese origins, and Sōtō, Rinzai and Ōbaku for the three main schools of Zen in Japan''

Japanese Zen refers to the Japanese forms of Zen Buddhism, an originally Chinese ...

.

The term Zen is derived from the

Japanese pronunciation of the

Middle Chinese

Middle Chinese (formerly known as Ancient Chinese) or the Qieyun system (QYS) is the historical variety of Chinese recorded in the '' Qieyun'', a rime dictionary first published in 601 and followed by several revised and expanded editions. The ...

word 禪 (''chán''), an abbreviation of 禪那 (''chánnà''), which is a Chinese transliteration of the

Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural diffusion ...

word ध्यान

''dhyāna'' ("

meditation

Meditation is a practice in which an individual uses a technique – such as mindfulness, or focusing the mind on a particular object, thought, or activity – to train attention and awareness, and achieve a mentally clear and emotionally calm ...

"). Zen emphasizes rigorous

self-restraint,

meditation-practice and the subsequent

insight

Insight is the understanding of a specific cause and effect within a particular context. The term insight can have several related meanings:

*a piece of information

*the act or result of understanding the inner nature of things or of seeing intui ...

into

nature of mind

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are p ...

(見性, Ch. ''jiànxìng,'' Jp. ''

kensho,'' "perceiving the true nature") and

nature of things (without arrogance or egotism), and the personal expression of this insight in daily life, especially for

the benefit of others. As such, it de-emphasizes knowledge alone of

sutra

''Sutra'' ( sa, सूत्र, translit=sūtra, translit-std=IAST, translation=string, thread)Monier Williams, ''Sanskrit English Dictionary'', Oxford University Press, Entry fo''sutra'' page 1241 in Indian literary traditions refers to an ap ...

s and doctrine, and favors direct understanding through

spiritual practice

A spiritual practice or spiritual discipline (often including spiritual exercises) is the regular or full-time performance of actions and activities undertaken for the purpose of inducing spiritual experiences and cultivating spiritual developm ...

and interaction with an accomplished teacher or Master.

Zen teaching draws from numerous sources of Sarvastivada meditation practice and Mahāyāna thought, especially

Yogachara

Yogachara ( sa, योगाचार, IAST: '; literally "yoga practice"; "one whose practice is yoga") is an influential tradition of Buddhist philosophy and psychology emphasizing the study of cognition, perception, and consciousness through ...

, the

Tathāgatagarbha sūtras

The Tathāgatagarbha sūtras are a group of Mahayana sutras that present the concept of the "womb" or "embryo" (''garbha'') of the tathāgata, the buddha. Every sentient being has the possibility to attain Buddhahood because of the ''tathāgat ...

, the

Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra

The ''Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra'' ( Sanskrit, "Discourse of the Descent into Laṅka" bo, ལང་ཀར་བཤེགས་པའི་མདོ་, Chinese:入楞伽經) is a prominent Mahayana Buddhist sūtra. This sūtra recounts a teachi ...

, and the

Huayan school

The Huayan or Flower Garland school of Buddhism (, from sa, अवतंसक, Avataṃsaka) is a tradition of Mahayana Buddhist philosophy that first flourished in China during the Tang dynasty (618-907). The Huayan worldview is based pri ...

, with their emphasis on

Buddha-nature

Buddha-nature refers to several related Mahayana Buddhist terms, including '' tathata'' ("suchness") but most notably ''tathāgatagarbha'' and ''buddhadhātu''. ''Tathāgatagarbha'' means "the womb" or "embryo" (''garbha'') of the "thus-gon ...

,

totality, and the

Bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva ( ; sa, 𑀩𑁄𑀥𑀺𑀲𑀢𑁆𑀢𑁆𑀯 (Brahmī), translit=bodhisattva, label=Sanskrit) or bodhisatva is a person who is on the path towards bodhi ('awakening') or Buddhahood.

In the Early Buddhist schools ...

-ideal. The

Prajñāpāramitā

A Tibetan painting with a Prajñāpāramitā sūtra at the center of the mandala

Prajñāpāramitā ( sa, प्रज्ञापारमिता) means "the Perfection of Wisdom" or "Transcendental Knowledge" in Mahāyāna and Theravāda ...

literature, as well as

Madhyamaka

Mādhyamaka ("middle way" or "centrism"; ; Tibetan: དབུ་མ་པ ; ''dbu ma pa''), otherwise known as Śūnyavāda ("the emptiness doctrine") and Niḥsvabhāvavāda ("the no ''svabhāva'' doctrine"), refers to a tradition of Buddhis ...

thought, have also been influential in the shaping of the

apophatic and sometimes

iconoclastic nature of Zen

rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate par ...

.

Furthermore, the

Chan School was also influenced by

Taoist philosophy, especially

Neo-Daoist

Xuanxue (), sometimes called Neo-Daoism (Neo-Taoism), is a metaphysical Post-classical history, post-classical Chinese philosophy from the Six Dynasties (222-589), bringing together Taoist and Confucianism, Confucian beliefs through revision and di ...

thought.

Etymology

The word ''Zen'' is derived from the

Japanese pronunciation (

kana

The term may refer to a number of syllabaries used to write Japanese phonological units, morae. Such syllabaries include (1) the original kana, or , which were Chinese characters ( kanji) used phonetically to transcribe Japanese, the most ...

: ぜん) of the

Middle Chinese

Middle Chinese (formerly known as Ancient Chinese) or the Qieyun system (QYS) is the historical variety of Chinese recorded in the '' Qieyun'', a rime dictionary first published in 601 and followed by several revised and expanded editions. The ...

word 禪 (

Middle Chinese

Middle Chinese (formerly known as Ancient Chinese) or the Qieyun system (QYS) is the historical variety of Chinese recorded in the '' Qieyun'', a rime dictionary first published in 601 and followed by several revised and expanded editions. The ...

:

ʑian ), which in turn is derived from the

Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural diffusion ...

word ''

dhyāna'' (ध्यान), which can be approximately translated as "contemplation", "absorption", or "

meditative state".

The actual Chinese term for the "Zen school" is 禪宗 (), while "Chan" just refers to the practice of meditation itself () or the study of meditation () though it is often used as an abbreviated form of ''Chánzong''.

"Zen" is traditionally a proper noun as it usually describes a particular Buddhist sect. In more recent times, the lowercase "zen" is used when discussing the philosophy and was officially added to the

Merriam-Webster

Merriam-Webster, Inc. is an American company that publishes reference books and is especially known for its dictionaries. It is the oldest dictionary publisher in the United States.

In 1831, George and Charles Merriam founded the company as ...

dictionary in 2018.

Practice

Dhyāna

The practice of

''dhyana'' or

meditation

Meditation is a practice in which an individual uses a technique – such as mindfulness, or focusing the mind on a particular object, thought, or activity – to train attention and awareness, and achieve a mentally clear and emotionally calm ...

, especially sitting meditation (坐禪,

Chinese: ''zuòchán'',

Japanese: ''

zazen

''Zazen'' (literally " seated meditation"; ja, 座禅; , pronounced ) is a meditative discipline that is typically the primary practice of the Zen Buddhist tradition.

However, the term is a general one not unique to Zen, and thus technical ...

'' / ざぜん) is a central part of Zen Buddhism.

Chinese Buddhism

The practice of

Buddhist meditation

Buddhist meditation is the practice of meditation in Buddhism. The closest words for meditation in the classical languages of Buddhism are ''bhāvanā'' ("mental development") and '' jhāna/dhyāna'' (mental training resulting in a calm and ...

first entered

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

through the translations of

An Shigao

An Shigao (, Korean: An Sego, Japanese: An Seikō, Vietnamese: An Thế Cao) (fl. c. 148-180 CE) was an early Buddhist missionary to China, and the earliest known translator of Indian Buddhist texts into Chinese. According to legend, he was a pri ...

(fl. c. 148–180 CE), and

Kumārajīva

Kumārajīva ( Sanskrit: कुमारजीव; , 344–413 CE) was a Buddhist monk, scholar, missionary and translator from the Kingdom of Kucha (present-day Aksu Prefecture, Xinjiang, China). Kumārajīva is seen as one of the greates ...

(334–413 CE), who both translated ''

Dhyāna sutras

The Dhyāna sutras ( ''chan jing'') (Japanese 禅経 ''zen-gyo'') or "meditation summaries" () or also known as The Zen Sutras are a group of early Buddhist meditation texts which are mostly based on the Yogacara meditation teachings of the Sarvās ...

'', which were influential early meditation texts mostly based on the

''Yogacara'' (

yoga

Yoga (; sa, योग, lit=yoke' or 'union ) is a group of physical, mental, and spiritual practices or disciplines which originated in ancient India and aim to control (yoke) and still the mind, recognizing a detached witness-consciou ...

praxis) teachings of the

Kashmiri Kashmiri may refer to:

* People or things related to the Kashmir Valley or the broader region of Kashmir

* Kashmiris, an ethnic group native to the Kashmir Valley

* Kashmiri language, their language

People with the name

* Kashmiri Saikia Baruah ...

Sarvāstivāda

The ''Sarvāstivāda'' (Sanskrit and Pali: 𑀲𑀩𑁆𑀩𑀢𑁆𑀣𑀺𑀯𑀸𑀤, ) was one of the early Buddhist schools established around the reign of Ashoka (3rd century BCE).Westerhoff, The Golden Age of Indian Buddhist Philosop ...

circa 1st–4th centuries CE.

[Deleanu, Florin (1992)]

Mindfulness of Breathing in the Dhyāna Sūtras

Transactions of the International Conference of Orientalists in Japan (TICOJ) 37, 42–57. Among the most influential early Chinese meditation texts include the ''

Anban Shouyi Jing'' (安般守意經, Sutra on

''ānāpānasmṛti''), the ''Zuochan Sanmei Jing'' (坐禪三昧經,Sutra of sitting dhyāna

samādhi

''Samadhi'' ( Pali and sa, समाधि), in Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, Sikhism and yogic schools, is a state of meditative consciousness. In Buddhism, it is the last of the eight elements of the Noble Eightfold Path. In the Ashtanga Yo ...

) and the ''Damoduoluo Chan Jing'' (達摩多羅禪經,

Dharmatrata dhyāna sutra)''.'' These early Chinese meditation works continued to exert influence on Zen practice well into the modern era. For example, the 18th century Rinzai Zen master

Tōrei Enji wrote a commentary on the ''Damoduoluo Chan Jing'' and used the ''Zuochan Sanmei Jing'' as source in the writing of this commentary.

Tōrei believed that the ''Damoduoluo Chan Jing'' had been authored by

Bodhidharma

Bodhidharma was a semi-legendary Buddhist monk who lived during the 5th or 6th century CE. He is traditionally credited as the transmitter of Chan Buddhism to China, and regarded as its first Chinese patriarch. According to a 17th century apo ...

.

While ''

dhyāna'' in a strict sense refers to the four ''dhyānas'', in

Chinese Buddhism

Chinese Buddhism or Han Buddhism ( zh, s=汉传佛教, t=漢傳佛教, p=Hànchuán Fójiào) is a Chinese form of Mahayana Buddhism which has shaped Chinese culture in a wide variety of areas including art, politics, literature, philosophy, ...

, ''dhyāna'' may refer to

various kinds of meditation techniques and their preparatory practices, which are necessary to practice ''dhyāna''. The five main types of meditation in the ''Dhyāna sutras'' are

''ānāpānasmṛti'' (mindfulness of breathing);

''paṭikūlamanasikāra'' meditation (mindfulness of the impurities of the body);

''maitrī'' meditation (loving-kindness); the contemplation on the twelve links of ''

pratītyasamutpāda

''Pratītyasamutpāda'' (Sanskrit: प्रतीत्यसमुत्पाद, Pāli: ''paṭiccasamuppāda''), commonly translated as dependent origination, or dependent arising, is a key doctrine in Buddhism shared by all schools of ...

''; and

contemplation on the Buddha.

[Ven. Dr. Yuanci]

A Study of the Meditation Methods in the DESM and Other Early Chinese Texts

The Buddhist Academy of China. According to the modern Chan master

Sheng Yen, these practices are termed the "five methods for stilling or pacifying the mind" and serve to focus and purify the mind, and support the development of the stages of

''dhyana''. Chan also shares the practice of the

four foundations of mindfulness

''Satipatthana'' ( pi, Satipaṭṭhāna, italic=yes; sa, smṛtyupasthāna, italic=yes) is a central practice in the Buddha's teachings, meaning "the establishment of mindfulness" or "presence of mindfulness", or alternatively "foundations of ...

and the Three Gates of Liberation (

emptyness or ''śūnyatā'', signlessness or ''animitta'', and

wishlessness or ''apraṇihita'') with early Buddhism and classic

Mahayana

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing br ...

.

Pointing to the nature of the mind

According to Charles Luk, in the earliest traditions of Chán, there was no fixed method or formula for teaching meditation, and all instructions were simply heuristic methods, to

point to the true

nature of the mind, also known as ''

Buddha-nature

Buddha-nature refers to several related Mahayana Buddhist terms, including '' tathata'' ("suchness") but most notably ''tathāgatagarbha'' and ''buddhadhātu''. ''Tathāgatagarbha'' means "the womb" or "embryo" (''garbha'') of the "thus-gon ...

''.

[Luk, Charles. ''The Secrets of Chinese Meditation.'' 1964. p. 44] According to Luk, this method is referred to as the "Mind Dharma", and exemplified in the story (in the

Flower Sermon

The Flower Sermon is a story of the origin of Zen Buddhism in which Gautama Buddha transmits direct '' prajñā'' (wisdom) to the disciple Mahākāśyapa. In the original Chinese, the story is ''Niān huā wēi xiào'' (拈花微笑, literally " ...

) of Śākyamuni Buddha holding up a flower silently, and

Mahākāśyapa

Mahākāśyapa ( pi, Mahākassapa) was one of the principal disciples of Gautama Buddha. He is regarded in Buddhism as an enlightened disciple, being foremost in ascetic practice. Mahākāśyapa assumed leadership of the monastic community fol ...

smiling as he understood.

A traditional formula of this is, "Chán points directly to the human mind, to enable people to see their true nature and become buddhas."

Observing the mind

According to John McRae, "one of the most important issues in the development of early Ch'an doctrine is the rejection of traditional meditation techniques," that is, gradual self-perfection and the practices of contemplation on the body impurities and the four foundations of mindfulness. According to John R. McRae the "first explicit statement of the sudden and direct approach that was to become the hallmark of Ch'an religious practice" is associated with the

East Mountain School. It is a method named "Maintaining the one without wavering" (''shou-i pu i,'' 守一不移), ''the one'' being the

nature of mind

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are p ...

, which is equated with Buddha-nature. According to Sharf, in this practice, one turns the attention from the objects of experience, to the

nature of mind

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are p ...

, the perceiving subject itself, which is equated with

Buddha-nature

Buddha-nature refers to several related Mahayana Buddhist terms, including '' tathata'' ("suchness") but most notably ''tathāgatagarbha'' and ''buddhadhātu''. ''Tathāgatagarbha'' means "the womb" or "embryo" (''garbha'') of the "thus-gon ...

. According to McRae, this type of meditation resembles the methods of "virtually all schools of Mahāyāna Buddhism," but differs in that "no preparatory requirements, no moral prerequisites or preliminary exercises are given," and is "without steps or gradations. One concentrates, understands, and is enlightened, all in one undifferentiated practice." Sharf notes that the notion of "Mind" came to be criticised by radical subitists, and was replaced by "No Mind," to avoid any reifications.

Meditation manuals

Early Chan texts also teach forms of meditation that are unique to

Mahāyāna

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing br ...

Buddhism, for example, the ''Treatise on the Essentials of Cultivating the Mind'', which depicts the teachings of the 7th-century

East Mountain school teaches a visualization of a sun disk, similar to that taught in the ''

Sutra of the Contemplation of the Buddha Amitáyus.''

Later Chinese Buddhists developed their own meditation manuals and texts, one of the most influential being the works of the

Tiantai

Tiantai or T'ien-t'ai () is an East Asian Buddhist school of Mahāyāna Buddhism that developed in 6th-century China. The school emphasizes the '' Lotus Sutra's'' doctrine of the "One Vehicle" (''Ekayāna'') as well as Mādhyamaka philosophy ...

patriarch,

Zhiyi

Zhiyi (; 538–597 CE) also Chen De'an (陳德安), is the fourth patriarch of the Tiantai tradition of Buddhism in China. His standard title was Śramaṇa Zhiyi (沙門智顗), linking him to the broad tradition of Indian asceticism. Zhiyi ...

. His works seemed to have exerted some influence on the earliest meditation manuals of the Chán school proper, an early work being the widely imitated and influential ''

Tso-chan-i'' (Principles of sitting meditation, c. 11th century), which doesn't outline a

vipassana

''Samatha'' ( Pāli; sa, शमथ ''śamatha''; ), "calm," "serenity," "tranquillity of awareness," and ''vipassanā'' ( Pāli; Sanskrit ''vipaśyanā''), literally "special, super (''vi-''), seeing (''-passanā'')", are two qualities of ...

practice which leads to wisdom (''

prajña''), but only recommends practicing samadhi which will lead to the discovery of

inherent wisdom already present in the mind.

Common contemporary meditation forms

Mindfulness of breathing

During sitting meditation (坐禅,

Ch. ''zuòchán,''

Jp. ''

zazen

''Zazen'' (literally " seated meditation"; ja, 座禅; , pronounced ) is a meditative discipline that is typically the primary practice of the Zen Buddhist tradition.

However, the term is a general one not unique to Zen, and thus technical ...

'',

Ko. ''jwaseon''), practitioners usually assume a position such as the

lotus position

Lotus position or Padmasana ( sa, पद्मासन, translit=padmāsana) is a cross-legged sitting meditation pose from ancient India, in which each foot is placed on the opposite thigh. It is an ancient asana in yoga, predating hatha ...

,

half-lotus,

Burmese, or

seiza, often using the

dhyāna mudrā. Often, a square or round cushion placed on a padded mat is used to sit on; in some other cases, a chair may be used.

To regulate the mind, Zen students are often directed towards

counting breaths. Either both exhalations and inhalations are counted, or one of them only. The count can be up to ten, and then this process is repeated until the mind is calmed. Zen teachers like

Omori Sogen

was a Japanese Rinzai Rōshi, a successor in the Tenryū-ji line of Rinzai Zen, and former president of Hanazono University, the Rinzai university in Kyoto, Japan. He became a priest in 1945.

Biography

Ōmori Sōgen was a teacher of Kashi ...

teach a series of long and deep exhalations and inhalations as a way to prepare for regular breath meditation. Attention is usually placed on the energy center (''

dantian

Dantian, dan t'ian, dan tien or tan t'ien is loosely translated as "elixir field", "sea of qi", or simply "energy center". Dantian are the "qi focus flow centers", important focal points for meditative and exercise techniques such as qigong, m ...

'') below the navel.

Zen teachers often promote

diaphragmatic breathing

Diaphragmatic breathing, abdominal breathing, belly breathing, or deep breathing, is breathing that is done by contracting the diaphragm, a muscle located horizontally between the thoracic cavity and abdominal cavity. Air enters the lungs as t ...

, stating that the breath must come from the lower abdomen (known as

hara

Hara may refer to:

Art and entertainment

* Hara (band), a Romanian pop-band

* ''Hara'' (film), a 2014 Kannada-language drama film

* ''Hara'' (sculpture), a 1989 artwork by Deborah Butterfield

* Goo Hara (1991-2019), South Korean idol singer

...

or tanden in Japanese), and that this part of the body should expand forward slightly as one breathes. Over time the breathing should become smoother, deeper and slower. When the counting becomes an encumbrance, the practice of simply following the natural rhythm of breathing with concentrated attention is recommended.

Silent Illumination and ''shikantaza''

A common form of sitting meditation is called "Silent illumination" (Ch. ''mòzhào,'' Jp''. mokushō''). This practice was traditionally promoted by the

Caodong

Caodong school () is a Chinese Chan Buddhist sect and one of the Five Houses of Chán.

Etymology

The key figure in the Caodong school was founder Dongshan Liangjie (807-869, 洞山良价 or Jpn. Tozan Ryokai). Some attribute the name "Cáodòng ...

school of

Chinese Chan and is associated with

Hongzhi Zhengjue

Hongzhi Zhengjue (, ), also sometimes called Tiantong Zhengjue (; ) (1091–1157), was an influential Chinese Chan Buddhist monk who authored or compiled several influential texts. Hongzhi's conception of ''silent illumination'' is of particular ...

(1091—1157) who wrote various works on the practice. This method derives from the Indian Buddhist practice of the union (

Skt. ''yuganaddha'') of ''

śamatha'' and ''

vipaśyanā

''Samatha'' (Pāli; sa, शमथ ''śamatha''; ), "calm," "serenity," "tranquillity of awareness," and ''vipassanā'' (Pāli; Sanskrit ''vipaśyanā''), literally "special, super (''vi-''), seeing (''-passanā'')", are two qualities of the ...

.''

In Hongzhi's practice of "nondual objectless meditation" the mediator strives to be aware of the totality of phenomena instead of focusing on a single object, without any interference,

conceptualizing,

grasping

A grasp is an act of taking, holding or seizing firmly with (or as if with) the hand. An example of a grasp is the handshake, wherein two people grasp one of each other's like hands.

In zoology particularly, prehensility is the quality of an app ...

,

goal seeking, or

subject-object duality.

This practice is also popular in the major schools of

Japanese Zen

:''See also Zen for an overview of Zen, Chan Buddhism for the Chinese origins, and Sōtō, Rinzai and Ōbaku for the three main schools of Zen in Japan''

Japanese Zen refers to the Japanese forms of Zen Buddhism, an originally Chinese ...

, but especially

Sōtō

Sōtō Zen or is the largest of the three traditional sects of Zen in Japanese Buddhism (the others being Rinzai and Ōbaku). It is the Japanese line of the Chinese Cáodòng school, which was founded during the Tang dynasty by Dòngsh� ...

, where it is more widely known as ''

Shikantaza (Ch. zhǐguǎn dǎzuò, "Just sitting").'' Considerable textual, philosophical, and phenomenological justification of the practice can be found throughout the work of the Japanese

Sōtō

Sōtō Zen or is the largest of the three traditional sects of Zen in Japanese Buddhism (the others being Rinzai and Ōbaku). It is the Japanese line of the Chinese Cáodòng school, which was founded during the Tang dynasty by Dòngsh� ...

Zen thinker

Dōgen

Dōgen Zenji (道元禅師; 26 January 1200 – 22 September 1253), also known as Dōgen Kigen (道元希玄), Eihei Dōgen (永平道元), Kōso Jōyō Daishi (高祖承陽大師), or Busshō Dentō Kokushi (仏性伝東国師), was a J ...

, especially in his ''

Shōbōgenzō

is the title most commonly used to refer to the collection of works written in Japan by the 13th century Buddhist monk and founder of the Sōtō Zen school, Eihei Dōgen. Several other works exist with the same title (see above), and it is so ...

'', for example in the "Principles of Zazen" and the "Universally Recommended Instructions for Zazen". While the Japanese and the Chinese forms are similar, they are distinct approaches.

Hua Tou and Kōan contemplation

During the

Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an Zhou dynasty (690–705), interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dyn ...

, ''gōng'àn (''

Jp. ''

kōan)'' literature became popular. Literally meaning "public case", they were stories or dialogues, describing teachings and interactions between

Zen master

Zen master is a somewhat vague English term that arose in the first half of the 20th century, sometimes used to refer to an individual who teaches Zen Buddhist meditation and practices, usually implying longtime study and subsequent authoriz ...

s and their students. These anecdotes give a demonstration of the master's insight. Kōan are meant to illustrate the non-conceptual insight (''

prajña'') that the Buddhist teachings point to. During the

Sòng dynasty, a new meditation method was popularized by figures such as

Dahui, which was called ''kanhua chan'' ("observing the phrase" meditation), which referred to contemplation on a single word or phrase (called the ''

huatou'', "critical phrase") of a ''gōng'àn''. In

Chinese Chan and

Korean Seon

Seon or Sŏn Buddhism ( Korean: 선, 禪; IPA: ʌn is the Korean name for Chan Buddhism, a branch of Mahāyāna Buddhism commonly known in English as Zen Buddhism. Seon is the Sino-Korean pronunciation of Chan () an abbreviation of 禪那 ( ...

, this practice of "observing the

''huatou''" (''hwadu'' in Korean) is a widely practiced method. It was taught by the influential Seon master

Chinul

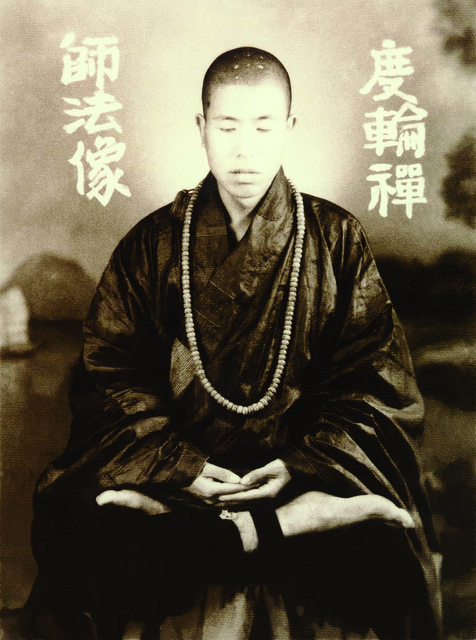

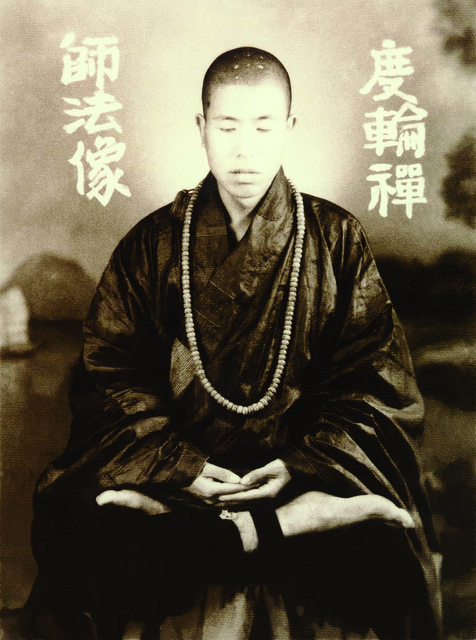

Jinul Puril Bojo Daesa (, "Bojo Jinul"; 1158–1210), often called Jinul or Chinul for short, was a Korean monk of the Goryeo period, who is considered to be the most influential figure in the formation of Korean Seon (Zen) Buddhism. He is credi ...

(1158–1210), and modern Chinese masters like

Sheng Yen and

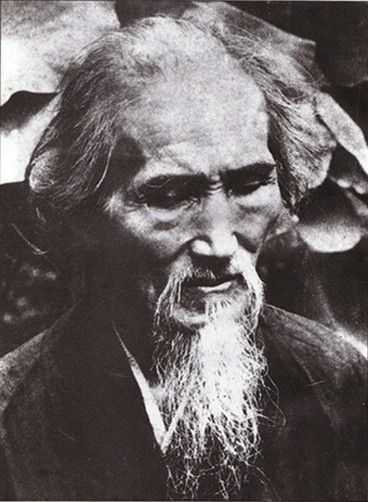

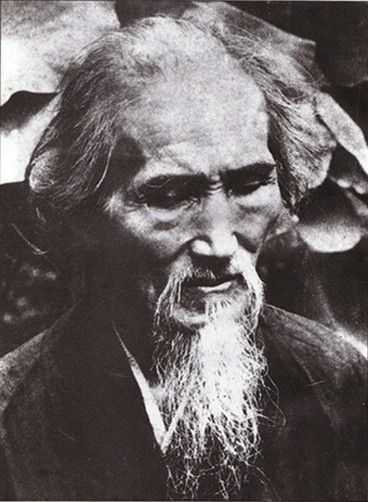

Xuyun

Xuyun or Hsu Yun (; 5 September 1840? – 13 October 1959) was a renowned Chinese Chan Buddhist master and an influential Buddhist teacher of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Early life

Xuyun was purportedly born on 5 September 1840 in Fujian, Q ...

. Yet, while Dahui famously criticised "silent illumination," he nevertheless "did not completely condemn quiet-sitting; in fact, he seems to have recommended it, at least to his monastic disciples."

In the Japanese

Rinzai school, ''

kōan'' introspection developed its own formalized style, with a standardized curriculum of ''

kōans'', which must be studied and "passed" in sequence. This process includes standardized "checking questions" (''sassho'') and common sets of "capping phrases" (''

jakugo'') or poetry citations that are memorized by students as answers. The Zen student's mastery of a given kōan is presented to the teacher in a private interview (referred to in Japanese as ''dokusan'', ''daisan'', or ''sanzen''). While there is no unique answer to a kōan, practitioners are expected to demonstrate their spiritual understanding through their responses. The teacher may approve or disapprove of the answer and guide the student in the right direction. The interaction with a teacher is central in Zen, but makes Zen practice also vulnerable to misunderstanding and exploitation. Kōan-inquiry may be practiced during ''

zazen

''Zazen'' (literally " seated meditation"; ja, 座禅; , pronounced ) is a meditative discipline that is typically the primary practice of the Zen Buddhist tradition.

However, the term is a general one not unique to Zen, and thus technical ...

'' (sitting meditation)'',

kinhin'' (walking meditation), and throughout all the activities of daily life. The goal of the practice is often termed ''

kensho'' (seeing one's true nature), and is to be followed by further practice to attain a natural, effortless, down-to-earth state of being, the "ultimate liberation", "knowing without any kind of defilement".

Kōan practice is particularly emphasized in

Rinzai, but it also occurs in other schools or branches of Zen depending on the teaching line.

Nianfo chan

''

Nianfo

Nianfo (, Japanese: , , vi, niệm Phật) is a term commonly seen in Pure Land Buddhism. In the context of Pure Land practice, it generally refers to the repetition of the name of Amitābha. It is a translation of Sanskrit '' '' (or, "recoll ...

'' (Jp. ''nembutsu,'' from Skt. ''

buddhānusmṛti'' "recollection of the Buddha") refers to the recitation of the Buddha's name, in most cases the Buddha

Amitabha. In Chinese Chan, the

Pure Land

A pure land is the celestial realm of a buddha or bodhisattva in Mahayana Buddhism. The term "pure land" is particular to East Asian Buddhism () and related traditions; in Sanskrit the equivalent concept is called a buddha-field (Sanskrit ). The ...

practice of ''nianfo'' based on the phrase ''Nāmó Āmítuófó'' (Homage to Amitabha) is a widely practiced form of Zen meditation. This practice was adopted from

Pure land Buddhism

Pure Land Buddhism (; ja, 浄土仏教, translit=Jōdo bukkyō; , also referred to as Amidism in English,) is a broad branch of Mahayana Buddhism focused on achieving rebirth in a Buddha's Buddha-field or Pure Land. It is one of the most wid ...

and

syncretized

Syncretism () is the practice of combining different beliefs and various schools of thought. Syncretism involves the merging or assimilation of several originally discrete traditions, especially in the theology and mythology of religion, th ...

with Chan meditation by Chinese figures such as

Yongming Yanshou,

Zhongfen Mingben, and

Tianru Weize. During the

late Ming, the harmonization of Pure land practices with Chan meditation was continued by figures such as

Yunqi Zhuhong and

Hanshan Deqing.

This practice, as well as its adaptation into the "''nembutsu

kōan''" was also used by the Japanese

Ōbaku school of Zen.

Bodhisattva virtues and vows

Since Zen is a form of

Mahayana Buddhism

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing br ...

, it is grounded on the schema of the

bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva ( ; sa, 𑀩𑁄𑀥𑀺𑀲𑀢𑁆𑀢𑁆𑀯 (Brahmī), translit=bodhisattva, label=Sanskrit) or bodhisatva is a person who is on the path towards bodhi ('awakening') or Buddhahood.

In the Early Buddhist schools ...

path, which is based on the practice of the "transcendent virtues" or "perfections" (

Skt. ''

pāramitā

''Pāramitā'' (Sanskrit, Pali: पारमिता) or ''pāramī'' (Pāli: पारमी), is a Buddhist term often translated as "perfection". It is described in Buddhist commentaries as noble character qualities generally associated wit ...

'', Ch. ''bōluómì'', Jp. ''baramitsu'') as well as the taking of the

bodhisattva vow

The Bodhisattva vow is a vow (Sanskrit: ''praṇidhāna,'' lit. aspiration or resolution) taken by some Mahāyāna Buddhists to achieve full buddhahood for the sake of all sentient beings. One who has taken the vow is nominally known as a bodhi ...

s. The most widely used list of six virtues is:

generosity

Generosity (also called largess) is the virtue of being liberal in giving, often as gifts. Generosity is regarded as a virtue by various world religions and philosophies, and is often celebrated in cultural and religious ceremonies. Scientific ...

,

moral training (incl.

five precepts

The Five precepts ( sa, pañcaśīla, italic=yes; pi, pañcasīla, italic=yes) or five rules of training ( sa, pañcaśikṣapada, italic=yes; pi, pañcasikkhapada, italic=yes) is the most important system of morality for Buddhist lay peo ...

),

patient endurance,

energy or effort,

meditation

Meditation is a practice in which an individual uses a technique – such as mindfulness, or focusing the mind on a particular object, thought, or activity – to train attention and awareness, and achieve a mentally clear and emotionally calm ...

(''

dhyana''),

wisdom

Wisdom, sapience, or sagacity is the ability to contemplate and act using knowledge, experience, understanding, common sense and insight. Wisdom is associated with attributes such as unbiased judgment, compassion, experiential self-knowledg ...

. An important source for these teachings is the

''Avatamsaka sutra'', which also outlines the grounds (''

bhumis'') or levels of the bodhisattva path. The

''pāramitās'' are mentioned in early Chan works such as

Bodhidharma

Bodhidharma was a semi-legendary Buddhist monk who lived during the 5th or 6th century CE. He is traditionally credited as the transmitter of Chan Buddhism to China, and regarded as its first Chinese patriarch. According to a 17th century apo ...

's ''

Two entrances and four practices'' and are seen as an important part of gradual cultivation (''jianxiu'') by later Chan figures like

Zongmi

Guifeng Zongmi () (780–1 February 841) was a Tang dynasty Buddhist scholar and bhikkhu, installed as fifth patriarch of the Huayan school as well as a patriarch of the Heze school of Southern Chan Buddhism. He wrote a number of works on the ...

.

An important element of this practice is the formal and ceremonial taking of

refuge in the three jewels,

bodhisattva vow

The Bodhisattva vow is a vow (Sanskrit: ''praṇidhāna,'' lit. aspiration or resolution) taken by some Mahāyāna Buddhists to achieve full buddhahood for the sake of all sentient beings. One who has taken the vow is nominally known as a bodhi ...

s and

precepts. Various sets of precepts are taken in Zen including the

five precepts

The Five precepts ( sa, pañcaśīla, italic=yes; pi, pañcasīla, italic=yes) or five rules of training ( sa, pañcaśikṣapada, italic=yes; pi, pañcasikkhapada, italic=yes) is the most important system of morality for Buddhist lay peo ...

,

"ten essential precepts", and the

sixteen bodhisattva precepts. This is commonly done in an

initiation ritual

Initiation is a rite of passage marking entrance or acceptance into a group or society. It could also be a formal admission to adulthood in a community or one of its formal components. In an extended sense, it can also signify a transformation ...

(

Ch. ''shòu jiè'',

Jp. ''Jukai'',

Ko. ''sugye,'' "receiving the precepts"'')'', which is also undertaken by

lay followers and marks a layperson as a formal Buddhist.

The

Chinese Buddhist practice of fasting (''zhai''), especially during the

uposatha days (Ch. ''zhairi,'' "days of fasting") can also be an element of Chan training. Chan masters may go on extended absolute fasts, as exemplified by

master Hsuan Hua's 35 day fast, which he undertook during the

Cuban missile crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

for the generation of merit.

Physical cultivation

Traditional martial arts, like

Japanese archery, other forms of Japanese ''

budō

is a Japanese term describing modern Japanese martial arts. Literally translated it means the "Martial Way", and may be thought of as the "Way of War" or the "Way of Martial Arts".

Etymology

Budō is a compound of the root ''bu'' ( 武:ぶ), ...

'' and

Chinese martial arts

Chinese martial arts, often called by the umbrella terms kung fu (; ), kuoshu () or wushu (), are multiple fighting styles that have developed over the centuries in Greater China. These fighting styles are often classified according to comm ...

(''gōngfu'') have also been seen as forms of zen praxis. This tradition goes back to the influential

Shaolin Monastery in

Henan

Henan (; or ; ; alternatively Honan) is a landlocked province of China, in the central part of the country. Henan is often referred to as Zhongyuan or Zhongzhou (), which literally means "central plain" or "midland", although the name is a ...

, which developed the first institutionalized form of ''gōngfu.'' By the

late Ming, Shaolin ''gōngfu'' was very popular and widespread, as evidenced by mentions in various forms of Ming literature (featuring staff wielding fighting monks like

Sun Wukong

The Monkey King, also known as Sun Wukong ( zh, t=孫悟空, s=孙悟空, first=t) in Mandarin Chinese, is a legendary mythical figure best known as one of the main characters in the 16th-century Chinese novel '' Journey to the West'' ( zh, ...

) and historical sources, which also speak of Shaolin's impressive monastic army that rendered military service to the state in return for patronage. These

Shaolin practices, which began to develop around the 12th century, were also traditionally seen as a form of Chan Buddhist inner cultivation (today called ''wuchan'', "martial chan"). The Shaolin arts also made use of Taoist physical exercises (

''taoyin'') breathing and

energy

In physics, energy (from Ancient Greek: ἐνέργεια, ''enérgeia'', “activity”) is the quantitative property that is transferred to a body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of work and in the form of ...

cultivation (''

qìgōng'') practices. They were seen as therapeutic practices, which improved "internal strength" (''neili''), health and longevity (lit. "nourishing life" ''yangsheng''), as well as means to spiritual liberation.

The influence of these Taoist practices can be seen in the work of Wang Zuyuan (ca. 1820–after 1882), a scholar and minor bureaucrat who studied at Shaolin. Wang's ''Illustrated Exposition of Internal Techniques'' (''Neigong tushuo'') shows how Shaolin exercises were drawn from Taoist methods like those of the

''Yi jin jing'' and

Eight pieces of brocade, possibly influenced by the

Ming dynasty's spirit of religious syncretism. According to the modern Chan master Sheng Yen,

Chinese Buddhism

Chinese Buddhism or Han Buddhism ( zh, s=汉传佛教, t=漢傳佛教, p=Hànchuán Fójiào) is a Chinese form of Mahayana Buddhism which has shaped Chinese culture in a wide variety of areas including art, politics, literature, philosophy, ...

has adopted

internal cultivation exercises from the

Shaolin tradition as ways to "harmonize the body and develop concentration in the midst of activity." This is because, "techniques for harmonizing the

vital energy

Vitalism is a belief that starts from the premise that "living organisms are fundamentally different from non-living entities because they contain some non-physical element or are governed by different principles than are inanimate things." Wher ...

are powerful assistants to the cultivation of ''

samadhi

''Samadhi'' ( Pali and sa, समाधि), in Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, Sikhism and yogic schools, is a state of meditative consciousness. In Buddhism, it is the last of the eight elements of the Noble Eightfold Path. In the Ashtanga Yo ...

'' and

spiritual insight."

Korean Seon

Seon or Sŏn Buddhism ( Korean: 선, 禪; IPA: ʌn is the Korean name for Chan Buddhism, a branch of Mahāyāna Buddhism commonly known in English as Zen Buddhism. Seon is the Sino-Korean pronunciation of Chan () an abbreviation of 禪那 ( ...

also has developed a similar form of active physical training, termed ''

Sunmudo

Sunmudo (/, literally ''the way of war of the Seon'') is a Korean Buddhist martial art based on Seon (also spelled Sun or Zen), which was revived during the 1970s and 1980s. The formal name of Sunmudo is ''Bulgyo Geumgang Yeong Gwan'' (Hangul: � ...

.''

In

Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

, the classic combat arts (''

budō

is a Japanese term describing modern Japanese martial arts. Literally translated it means the "Martial Way", and may be thought of as the "Way of War" or the "Way of Martial Arts".

Etymology

Budō is a compound of the root ''bu'' ( 武:ぶ), ...

'') and zen practice have been in contact since the embrace of

Rinzai Zen by the

Hōjō clan

The was a Japanese samurai family who controlled the hereditary title of ''shikken'' (regent) of the Kamakura shogunate between 1203 and 1333. Despite the title, in practice the family wielded actual political power in Japan during this period ...

in the 13th century, who applied zen discipline to their martial practice. One influential figure in this relationship was the Rinzai priest

Takuan Sōhō

was a Japanese Buddhist prelate during the Sengoku and early Edo Periods of Japanese history. He was a major figure in the Rinzai school of Zen Buddhism. Noted for his calligraphy, poetry, tea ceremony, he is also popularly credited with the inv ...

who was well known for his writings on zen and ''

budō

is a Japanese term describing modern Japanese martial arts. Literally translated it means the "Martial Way", and may be thought of as the "Way of War" or the "Way of Martial Arts".

Etymology

Budō is a compound of the root ''bu'' ( 武:ぶ), ...

'' addressed to the

samurai

were the hereditary military nobility and officer caste of medieval and early-modern Japan from the late 12th century until their abolition in 1876. They were the well-paid retainers of the '' daimyo'' (the great feudal landholders). They ...

class (especially his ''

The Unfettered Mind'') . The

Rinzai school also adopted certain Taoist energy practices. They were introduced by

Hakuin

was one of the most influential figures in Japanese Zen Buddhism. He is regarded as the reviver of the Rinzai school from a moribund period of stagnation, focusing on rigorous training methods integrating meditation and koan practice.

Biograp ...

(1686–1769) who learned various techniques from a hermit named Hakuyu who helped Hakuin cure his "Zen sickness" (a condition of physical and mental exhaustion). These energetic practices, known as ''Naikan'', are based on focusing the mind and one's vital energy (''ki'') on the ''

tanden'' (a spot slightly below the navel).

The arts

Certain

arts

The arts are a very wide range of human practices of creative expression, storytelling and cultural participation. They encompass multiple diverse and plural modes of thinking, doing and being, in an extremely broad range of media. Both ...

such as

painting

Painting is the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called the "matrix" or "support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with a brush, but other implements, such as knives, sponges, and a ...

,

calligraphy

Calligraphy (from el, link=y, καλλιγραφία) is a visual art related to writing. It is the design and execution of lettering with a pen, ink brush, or other writing instrument. Contemporary calligraphic practice can be defined ...

,

poetry

Poetry (derived from the Greek '' poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meani ...

,

gardening

Gardening is the practice of growing and cultivating plants as part of horticulture. In gardens, ornamental plants are often grown for their flowers, foliage, or overall appearance; useful plants, such as root vegetables, leaf vegetables, frui ...

,

flower arrangement

Floral design or flower arrangement is the art of using plant materials and flowers to create an eye-catching and balanced composition or display. Evidence of refined floristry is found as far back as the culture of ancient Egypt. Professionally ...

,

tea ceremony

An East Asian tea ceremony, or ''Chádào'' (), or ''Dado'' ( ko, 다도 (茶道)), is a ceremonially ritualized form of making tea (茶 ''cha'') practiced in East Asia by the Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans. The tea ceremony (), literally transl ...

and others have also been used as part of zen training and practice. Classical Chinese arts like

brush painting and

calligraphy

Calligraphy (from el, link=y, καλλιγραφία) is a visual art related to writing. It is the design and execution of lettering with a pen, ink brush, or other writing instrument. Contemporary calligraphic practice can be defined ...

were used by Chan monk painters such as

Guanxiu

Guanxiu () was a celebrated Buddhist monk, painter, poet, and calligrapher. His greatest works date from the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. The collapse of the central Tang government in 907, meant artists and craftsmen lost their most p ...

and

Muqi Fachang to communicate their spiritual understanding in unique ways to their students. Zen paintings are sometimes termed ''zenga'' in Japanese.

Hakuin

was one of the most influential figures in Japanese Zen Buddhism. He is regarded as the reviver of the Rinzai school from a moribund period of stagnation, focusing on rigorous training methods integrating meditation and koan practice.

Biograp ...

is one Japanese Zen master who was known to create a large corpus of unique

''sumi-e'' (ink and wash paintings) and

Japanese calligraphy

also called is a form of calligraphy, or artistic writing, of the Japanese language.

Written Japanese was originally based on Chinese characters only, but the advent of the hiragana and katakana Japanese syllabaries resulted in intrin ...

to communicate zen in a visual way. His work and that of his disciples were widely influential in

Japanese Zen

:''See also Zen for an overview of Zen, Chan Buddhism for the Chinese origins, and Sōtō, Rinzai and Ōbaku for the three main schools of Zen in Japan''

Japanese Zen refers to the Japanese forms of Zen Buddhism, an originally Chinese ...

. Another example of Zen arts can be seen in the short lived

Fuke sect The term "Fuke" is Japanese and may refer to:

* Fuke, known as Puhua, in Chinese, the legendary precursor to the eponymous Fuke Zen school of Buddhism in Japan

* Fuke Zen The term "Fuke" is Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or re ...

of Japanese Zen, which practiced a unique form of "blowing zen" (''

suizen'') by playing the ''

shakuhachi

A is a Japanese and ancient Chinese longitudinal, end-blown flute that is made of bamboo.

The bamboo end-blown flute now known as the was developed in Japan in the 16th century and is called the . '' bamboo flute.

Intensive group practice

Intensive group meditation may be practiced by serious Zen practitioners. In the Japanese language, this practice is called ''

sesshin

A ''sesshin'' (接心, or also 摂心/攝心 literally "touching the heart-mind") is a period of intensive meditation (zazen) in a Zen monastery.

While the daily routine in the monastery requires the monks to meditate several hours a day, d ...

''. While the daily routine may require monks to meditate for several hours each day, during the intensive period they devote themselves almost exclusively to zen practice. The numerous 30–50 minute long sitting meditation (''zazen'') periods are interwoven with rest breaks, ritualized formal meals (Jp. ''

oryoki''), and short periods of work (Jp. ''

samu'') that are to be performed with the same state of mindfulness. In modern Buddhist practice in Japan,

Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the no ...

, and the West, lay students often attend these intensive practice sessions or retreats. These are held at many Zen centers or temples.

Chanting and rituals

Most Zen monasteries, temples and centers perform various

ritual

A ritual is a sequence of activities involving gestures, words, actions, or objects, performed according to a set sequence. Rituals may be prescribed by the traditions of a community, including a religious community. Rituals are characterized ...

s, services and

ceremonies

A ceremony (, ) is a unified ritualistic event with a purpose, usually consisting of a number of artistic components, performed on a special occasion.

The word may be of Etruscan origin, via the Latin '' caerimonia''.

Church and civil (secula ...

(such as initiation ceremonies and

funerals

A funeral is a ceremony connected with the final disposition of a corpse, such as a burial or cremation, with the attendant observances. Funerary customs comprise the complex of beliefs and practices used by a culture to remember and respect th ...

), which are always accompanied by the chanting of verses, poems or

sutras. There are also ceremonies that are specifically for the purpose of sutra recitation (Ch. ''niansong'', Jp. ''nenju'') itself.

Zen schools may have an official sutra book that collects these writings (in Japanese, these are called ''kyohon''). Practitioners may chant major

Mahayana sutras

The Mahāyāna sūtras are a broad genre of Buddhist scriptures (''sūtra'') that are accepted as canonical and as ''buddhavacana'' ("Buddha word") in Mahāyāna Buddhism. They are largely preserved in the Chinese Buddhist canon, the Tibet ...

such as the ''

Heart Sutra'' and chapter 25 of the ''

Lotus Sutra

The ''Lotus Sūtra'' ( zh, 妙法蓮華經; sa, सद्धर्मपुण्डरीकसूत्रम्, translit=Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sūtram, lit=Sūtra on the White Lotus of the True Dharma, italic=) is one of the most influ ...

'' (often called the "

Avalokiteśvara

In Buddhism, Avalokiteśvara (Sanskrit: अवलोकितेश्वर, IPA: ) is a bodhisattva who embodies the compassion of all Buddhas. He has 108 avatars, one notable avatar being Padmapāṇi (lotus bearer). He is variably depicted, ...

Sutra").

Dhāraṇīs and Zen poems may also be part of a Zen temple

liturgy

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. ''Liturgy'' can also be used to refer specifically to public worship by Christians. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and partic ...

, including texts like the ''

Song of the Precious Mirror Samadhi'', the ''

Sandokai'', the ''

Nīlakaṇṭha Dhāraṇī

The , also known as the , or Great Compassion Dhāraṇī / Mantra (Chinese: 大悲咒, ''Dàbēi zhòu''; Japanese: 大悲心陀羅尼, ''Daihishin darani'' or 大悲呪, ''Daihi shu''; Vietnamese: ''Chú đại bi'' or ''Đại bi tâm đà ...

'', and the ''

Uṣṇīṣa Vijaya Dhāraṇī Sūtra.''

The ''

butsudan

A , sometimes spelled Butudan, is a shrine commonly found in temples and homes in Japanese Buddhist cultures. A ''butsudan'' is either a defined, often ornate platform or simply a wooden cabinet sometimes crafted with doors that enclose and p ...

'' is the

altar

An altar is a table or platform for the presentation of religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. Altars are found at shrines, temples, churches, and other places of worship. They are used particularly in pagan ...

in a monastery, temple or a lay person's home, where offerings are made to the images of the Buddha,

bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva ( ; sa, 𑀩𑁄𑀥𑀺𑀲𑀢𑁆𑀢𑁆𑀯 (Brahmī), translit=bodhisattva, label=Sanskrit) or bodhisatva is a person who is on the path towards bodhi ('awakening') or Buddhahood.

In the Early Buddhist schools ...

s and deceased family members and ancestors. Rituals usually center on major Buddhas or bodhisattvas like

Avalokiteśvara

In Buddhism, Avalokiteśvara (Sanskrit: अवलोकितेश्वर, IPA: ) is a bodhisattva who embodies the compassion of all Buddhas. He has 108 avatars, one notable avatar being Padmapāṇi (lotus bearer). He is variably depicted, ...

(see

Guanyin

Guanyin () is a Bodhisattva associated with compassion. She is the East Asian representation of Avalokiteśvara ( sa, अवलोकितेश्वर) and has been adopted by other Eastern religions, including Chinese folk religion. She ...

),

Kṣitigarbha

Kṣitigarbha ( sa, क्षितिगर्भ, , bo, ས་ཡི་སྙིང་པོ་ Wylie: ''sa yi snying po'') is a bodhisattva primarily revered in East Asian Buddhism and usually depicted as a Buddhist monk. His name may be t ...

and

Manjushri

Mañjuśrī (Sanskrit: मञ्जुश्री) is a ''bodhisattva'' associated with '' prajñā'' (wisdom) in Mahāyāna Buddhism. His name means "Gentle Glory" in Sanskrit. Mañjuśrī is also known by the fuller name of Mañjuśrīkumāra ...

.

An important element in Zen ritual practice is the performance of ritual

prostrations

Prostration is the gesture of placing one's body in a reverentially or submissively prone position. Typically prostration is distinguished from the lesser acts of bowing or kneeling by involving a part of the body above the knee, especially ...

(Jp. ''raihai'') or bows.

One popular form of ritual in Japanese Zen is ''

Mizuko kuyō'' (Water child) ceremonies, which are performed for those who have had a

miscarriage

Miscarriage, also known in medical terms as a spontaneous abortion and pregnancy loss, is the death of an embryo or fetus before it is able to survive independently. Miscarriage before 6 weeks of gestation is defined by ESHRE as biochemica ...

,

stillbirth

Stillbirth is typically defined as fetal death at or after 20 or 28 weeks of pregnancy, depending on the source. It results in a baby born without signs of life. A stillbirth can result in the feeling of guilt or grief in the mother. The term ...

, or

abortion

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. An abortion that occurs without intervention is known as a miscarriage or "spontaneous abortion"; these occur in approximately 30% to 40% of pre ...

. These ceremonies are also performed in American Zen Buddhism.

A widely practiced ritual in

Chinese Chan is variously called the "Rite for releasing the

hungry ghost

Hungry ghost is a concept in Buddhism, and Chinese traditional religion, representing beings who are driven by intense emotional needs in an animalistic way.

The terms ' literally "hungry ghost", are the Chinese translation of the term ''pret ...

s" or the "Releasing flaming mouth". The ritual might date back to the

Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an Zhou dynasty (690–705), interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dyn ...

, and was very popular during the Ming and Qing dynasties, when

Chinese Esoteric Buddhist practices became diffused throughout

Chinese Buddhism

Chinese Buddhism or Han Buddhism ( zh, s=汉传佛教, t=漢傳佛教, p=Hànchuán Fójiào) is a Chinese form of Mahayana Buddhism which has shaped Chinese culture in a wide variety of areas including art, politics, literature, philosophy, ...

. The Chinese holiday of the

Ghost Festival

The Ghost Festival, also known as the Zhongyuan Festival (traditional Chinese: 中元節; simplified Chinese: ) in Taoism and Yulanpen Festival () in Buddhism, is a traditional Taoist and Buddhist festival held in certain East Asian countrie ...

might also be celebrated with similar rituals for the dead. These ghost rituals are a source of contention in modern Chinese Chan, and masters such as

Sheng Yen criticize the practice for not having "any basis in Buddhist teachings".

Another important type of ritual practiced in Zen are various repentance or confession rituals (Jp. ''zange'') that were widely practiced in all forms of Chinese Mahayana Buddhism. One popular Chan text on this is known as the Emperor Liang Repentance Ritual, composed by Chan master Baozhi.

Dogen also wrote a treatise on repentance, the ''Shushogi.'' Other rituals could include rites dealing with

local deities (''

kami

are the deities, divinities, spirits, phenomena or "holy powers", that are venerated in the Shinto religion. They can be elements of the landscape, forces of nature, or beings and the qualities that these beings express; they can also be the sp ...

'' in Japan), and ceremonies on Buddhist holidays such as

Buddha's Birthday

Buddha's Birthday (also known as Buddha Jayanti, also known as his day of enlightenment – Buddha Purnima, Buddha Pournami) is a Buddhist festival that is celebrated in most of East Asia and South Asia commemorating the birth of the Prince ...

.

Funerals

A funeral is a ceremony connected with the final disposition of a corpse, such as a burial or cremation, with the attendant observances. Funerary customs comprise the complex of beliefs and practices used by a culture to remember and respect th ...

are also an important ritual and are a common point of contact between Zen monastics and the laity. Statistics published by the Sōtō school state that 80 percent of Sōtō laymen visit their temple only for reasons having to do with funerals and death. Seventeen percent visit for spiritual reasons and 3 percent visit a Zen priest at a time of personal trouble or crisis.

Esoteric practices

Depending on the tradition,

esoteric methods such as

mantra

A mantra ( Pali: ''manta'') or mantram (मन्त्रम्) is a sacred utterance, a numinous sound, a syllable, word or phonemes, or group of words in Sanskrit, Pali and other languages believed by practitioners to have religious, ...

and

dhāraṇī

Dharanis ( IAST: ), also known as ''Parittas'', are Buddhist chants, mnemonic codes, incantations, or recitations, usually the mantras consisting of Sanskrit or Pali phrases. Believed to be protective and with powers to generate merit for the ...

are also used for different purposes including meditation practice, protection from evil, invoking great compassion, invoking the power of certain bodhisattvas, and are chanted during ceremonies and rituals. In the

Kwan Um school of Zen for example, a mantra of

Guanyin

Guanyin () is a Bodhisattva associated with compassion. She is the East Asian representation of Avalokiteśvara ( sa, अवलोकितेश्वर) and has been adopted by other Eastern religions, including Chinese folk religion. She ...

("''Kwanseum Bosal''") is used during sitting meditation. The

Heart Sutra Mantra is also another mantra that is used in Zen during various rituals. Another example is the

Mantra of Light

The Mantra of Light, also called the ''Mantra of the Unfailing Rope Snare'', is an important mantra of the Shingon and Kegon sects of Buddhism, but is not emphasized in other Vajrayana sects of Buddhism. It is taken from the ''Amoghapāśa-kalpar ...

(''kōmyō shingon''), which is common in Japanese

Soto Zen Soto may refer to:

Geography

*Soto (Aller), parish in Asturias, Spain

* Soto (Las Regueras), parish in Asturias, Spain

* Soto, Curaçao, Netherlands Antilles

*Soto, Russia, a rural locality (a ''selo'') in Megino-Kangalassky District of the Sakha ...

and was derived from the

Shingon

Shingon monks at Mount Koya

is one of the major schools of Buddhism in Japan and one of the few surviving Vajrayana lineages in East Asia, originally spread from India to China through traveling monks such as Vajrabodhi and Amoghavajra.

Kn ...

sect.

In

Chinese Chan, the usage of esoteric mantras in Zen goes back to the

Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an Zhou dynasty (690–705), interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dyn ...

. There is evidence that

Chan Buddhists

Chan may refer to:

Places

* Chan (commune), Cambodia

*Chan Lake, by Chan Lake Territorial Park in Northwest Territories, Canada

People

*Chan (surname), romanization of various Chinese surnames (including 陳, 曾, 詹, 戰, and 田)

* Chan Caldw ...

adopted practices from

Chinese Esoteric Buddhism

Chinese Esoteric Buddhism refers to traditions of Tantra and Esoteric Buddhism that have flourished among the Chinese people. The Tantric masters Śubhakarasiṃha, Vajrabodhi and Amoghavajra, established the Esoteric Buddhist ''Zhenyan'' (, "true ...

in

findings from Dunhuang. According to Henrik Sørensen, several successors of

Shenxiu

Yuquan Shenxiu (, 606?–706) was one of the most influential Chan masters of his day, a Patriarch of the East Mountain Teaching of Chan Buddhism. Shenxiu was Dharma heir of Daman Hongren (601–674), honoured by Wu Zetian (r. 690–705) of t ...

(such as Jingxian and Yixing) were also students of the

Zhenyan (Mantra) school. Influential esoteric

dhāraṇī

Dharanis ( IAST: ), also known as ''Parittas'', are Buddhist chants, mnemonic codes, incantations, or recitations, usually the mantras consisting of Sanskrit or Pali phrases. Believed to be protective and with powers to generate merit for the ...

, such as the ''

Uṣṇīṣa Vijaya Dhāraṇī Sūtra'' and the ''

Nīlakaṇṭha Dhāraṇī

The , also known as the , or Great Compassion Dhāraṇī / Mantra (Chinese: 大悲咒, ''Dàbēi zhòu''; Japanese: 大悲心陀羅尼, ''Daihishin darani'' or 大悲呪, ''Daihi shu''; Vietnamese: ''Chú đại bi'' or ''Đại bi tâm đà ...

'', also begin to be cited in the literature of the Baotang school during the Tang dynasty. Many mantras have been preserved since the Tang period and continue to be practiced in modern Chan monasteries. One common example is the

Śūraṅgama Mantra,which has been heavily propagated by various prominent Chan monks, such as Venerable

Hsuan Hua

Hsuan Hua (; April 16, 1918 – June 7, 1995), also known as An Tzu, Tu Lun and Master Hua by his Western disciples, was a Chinese monk of Chan Buddhism and a contributing figure in bringing Chinese Buddhism to the United States in the lat ...

who founded the

City of Ten Thousand Buddhas. Another example of esoteric rituals practiced by the Chan school is the Mengshan Rite for Feeding

Hungry Ghosts

Hungry ghost is a concept in Buddhism, and Chinese traditional religion, representing beings who are driven by intense emotional needs in an animalistic way.

The terms ' literally "hungry ghost", are the Chinese translation of the term ''pret ...

, which is practiced by both monks and laypeople during the

Hungry Ghost Festival. Chan repentance rituals, such as the

Liberation Rite of Water and Land

The Liberation Rite of Water and Land () is a Chinese Buddhist ritual performed by temples and presided over by high monks. The service is often credited as one of the greatest rituals in Chinese Buddhism, as it is also the most elaborate and req ...

, also involve various esoteric aspects, including the invocation of esoteric deities such as the

Five Wisdom Buddhas

5 is a number, numeral, and glyph.

5, five or number 5 may also refer to:

* AD 5, the fifth year of the AD era

* 5 BC, the fifth year before the AD era

Literature

* ''5'' (visual novel), a 2008 visual novel by Ram

* ''5'' (comics), an awar ...

and the

Ten Wisdom Kings.

There is documentation that monks living at

Shaolin temple

Shaolin Monastery (少林寺 ''Shàolínsì''), also known as Shaolin Temple, is a renowned monastic institution recognized as the birthplace of Chan Buddhism and the cradle of Shaolin Kung Fu. It is located at the foot of Wuru Peak of the So ...

during the eighth century performed esoteric practices there such as mantra and dharani, and that these also influenced Korean Seon Buddhism. During the

Joseon dynasty

Joseon (; ; Middle Korean: 됴ᇢ〯션〮 Dyǒw syéon or 됴ᇢ〯션〯 Dyǒw syěon), officially the Great Joseon (; ), was the last dynastic kingdom of Korea, lasting just over 500 years. It was founded by Yi Seong-gye in July 1392 and r ...

, the Seon school was not only the dominant tradition in Korea, but it was also highly inclusive and ecumenical in its doctrine and practices, and this included Esoteric Buddhist lore and rituals (that appear in Seon literature from the 15th century onwards). According to Sørensen, the writings of several Seon masters (such as

Hyujeong) reveal they were esoteric adepts.

In

Japanese Zen

:''See also Zen for an overview of Zen, Chan Buddhism for the Chinese origins, and Sōtō, Rinzai and Ōbaku for the three main schools of Zen in Japan''

Japanese Zen refers to the Japanese forms of Zen Buddhism, an originally Chinese ...

, the use of esoteric practices within Zen is sometimes termed "mixed Zen" (''kenshū zen'' 兼修禪), and the figure of

Keizan Jōkin (1264–1325) is seen as introducing this into the

Soto school Soto may refer to:

Geography

* Soto (Aller), parish in Asturias, Spain

* Soto (Las Regueras), parish in Asturias, Spain

* Soto, Curaçao, Netherlands Antilles

* Soto, Russia, a rural locality (a ''selo'') in Megino-Kangalassky District of the Sak ...

. The Japanese founder of the Rinzai school,

Myōan Eisai

was a Japanese Buddhist priest, credited with founding the Rinzai school, the Japanese line of the Linji school of Zen Buddhism. In 1191, he introduced this Zen approach to Japan, following his trip to China from 1187 to 1191, during which he w ...

(1141–1215) was also a well known practitioner of esoteric Buddhism and wrote various works on the subject.

According to William Bodiford, a very common

dhāraṇī

Dharanis ( IAST: ), also known as ''Parittas'', are Buddhist chants, mnemonic codes, incantations, or recitations, usually the mantras consisting of Sanskrit or Pali phrases. Believed to be protective and with powers to generate merit for the ...

in Japanese Zen is the

Śūraṅgama spell (''Ryōgon shu'' 楞嚴呪; T. 944A), which is repeatedly chanted during summer training retreats as well as at "every important monastic ceremony throughout the year" in Zen monasteries. Some Zen temples also perform esoteric rituals, such as the

homa ritual, which is performed at the Soto temple of Eigen-ji (in

Saitama prefecture). As Bodiford writes, "perhaps the most notable examples of this phenomenon is the ambrosia gate (''kanro mon'' 甘露門) ritual performed at every Sōtō Zen temple", which is associated feeding

hungry ghost

Hungry ghost is a concept in Buddhism, and Chinese traditional religion, representing beings who are driven by intense emotional needs in an animalistic way.

The terms ' literally "hungry ghost", are the Chinese translation of the term ''pret ...

s,

ancestor memorial rites and the

ghost festival

The Ghost Festival, also known as the Zhongyuan Festival (traditional Chinese: 中元節; simplified Chinese: ) in Taoism and Yulanpen Festival () in Buddhism, is a traditional Taoist and Buddhist festival held in certain East Asian countrie ...

. Bodiford also notes that formal Zen rituals of

Dharma transmission

In Chan and Zen Buddhism, dharma transmission is a custom in which a person is established as a "successor in an unbroken lineage of teachers and disciples, a spiritual 'bloodline' (''kechimyaku'') theoretically traced back to the Buddha himse ...

often involve esoteric initiations.

Doctrine

Zen teachings can be likened to "the finger pointing at the moon". Zen teachings point to the moon,

awakening, "a realization of the unimpeded interpenetration of the

dharmadhatu

Dharmadhatu ( Sanskrit) is the 'dimension', 'realm' or 'sphere' (dhātu) of the Dharma or Absolute Reality.

Definition

In Mahayana Buddhism, dharmadhātu ( bo, chos kyi dbyings; ) means "realm of phenomena", "realm of truth", and of the noume ...

". But the Zen-tradition also warns against taking its teachings, the pointing finger, to be this insight itself.

Buddhist Mahayana influences

Though Zen-narrative states that it is a "special transmission outside scriptures", which "did not stand upon words", Zen does have a rich doctrinal background that is firmly grounded in the

Buddhist tradition. It was thoroughly influenced by

Mahayana

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing br ...

teachings on the

bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva ( ; sa, 𑀩𑁄𑀥𑀺𑀲𑀢𑁆𑀢𑁆𑀯 (Brahmī), translit=bodhisattva, label=Sanskrit) or bodhisatva is a person who is on the path towards bodhi ('awakening') or Buddhahood.

In the Early Buddhist schools ...

path, Chinese

Madhyamaka

Mādhyamaka ("middle way" or "centrism"; ; Tibetan: དབུ་མ་པ ; ''dbu ma pa''), otherwise known as Śūnyavāda ("the emptiness doctrine") and Niḥsvabhāvavāda ("the no ''svabhāva'' doctrine"), refers to a tradition of Buddhis ...

(''

Sānlùn''),

Yogacara

Yogachara ( sa, योगाचार, IAST: '; literally "yoga practice"; "one whose practice is yoga") is an influential tradition of Buddhist philosophy and psychology emphasizing the study of cognition, perception, and consciousness through ...

(''

Wéishí''), ''

Prajñaparamita,'' the ''

Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra

The ''Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra'' ( Sanskrit, "Discourse of the Descent into Laṅka" bo, ལང་ཀར་བཤེགས་པའི་མདོ་, Chinese:入楞伽經) is a prominent Mahayana Buddhist sūtra. This sūtra recounts a teachi ...

'', and other

Buddha nature

Buddha-nature refers to several related Mahayana Buddhist terms, including '' tathata'' ("suchness") but most notably ''tathāgatagarbha'' and ''buddhadhātu''. ''Tathāgatagarbha'' means "the womb" or "embryo" (''garbha'') of the "thus-gone ...

texts. The influence of

Madhyamaka

Mādhyamaka ("middle way" or "centrism"; ; Tibetan: དབུ་མ་པ ; ''dbu ma pa''), otherwise known as Śūnyavāda ("the emptiness doctrine") and Niḥsvabhāvavāda ("the no ''svabhāva'' doctrine"), refers to a tradition of Buddhis ...

and ''

Prajñaparamita'' can be discerned in the stress on non-conceptual wisdom (''

prajña'') and the

apophatic language of Zen literature.

The philosophy of the

Huayan

The Huayan or Flower Garland school of Buddhism (, from sa, अवतंसक, Avataṃsaka) is a tradition of Mahayana Buddhist philosophy that first flourished in China during the Tang dynasty (618-907). The Huayan worldview is based primar ...

school also had an influence on

Chinese Chan. One example is the Huayan doctrine of the

interpenetration of phenomena, which also makes use of native Chinese philosophical concepts such as principle (''li'') and phenomena (''shi''). The Huayan

theory of the Fourfold Dharmadhatu also influenced the

Five Ranks

The ''Five Ranks'' (; ) is a poem consisting of five stanzas describing the stages of realization in the practice of Zen Buddhism. It expresses the interplay of absolute and relative truth and the fundamental non-dualism of Buddhist teaching.

...

of

Dongshan Liangjie

Dongshan Liangjie (807–869) (; ) was a Chan Buddhist monk of the Tang dynasty. He founded the Caodong school (), which was transmitted to Japan in the thirteenth century (Song-Yuan era) by Dōgen and developed into the Sōtō school of Zen. ...

(806–869), the founder of the

Caodong

Caodong school () is a Chinese Chan Buddhist sect and one of the Five Houses of Chán.

Etymology

The key figure in the Caodong school was founder Dongshan Liangjie (807-869, 洞山良价 or Jpn. Tozan Ryokai). Some attribute the name "Cáodòng ...

Chan lineage.

Buddha-nature and subitism

Central in the doctrinal development of Chan Buddhism was the notion of

Buddha-nature

Buddha-nature refers to several related Mahayana Buddhist terms, including '' tathata'' ("suchness") but most notably ''tathāgatagarbha'' and ''buddhadhātu''. ''Tathāgatagarbha'' means "the womb" or "embryo" (''garbha'') of the "thus-gon ...

, the idea that the awakened mind of a Buddha is already present in each sentient being (''pen chueh'' in Chinese Buddhism, ''

hongaku

Hongaku () is an East Asian Buddhist doctrine often translated as "inherent", "innate", "intrinsic" or "original" enlightenment and is the view that all sentient beings already are enlightened or awakened in some way. It is closely tied with the ...

'' in

Japanese Zen