ZETA (fusion reactor) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

ZETA, short for Zero Energy Thermonuclear Assembly, was a major experiment in the early history of

ZETA, short for Zero Energy Thermonuclear Assembly, was a major experiment in the early history of

A potential solution to the confinement problem had been detailed in 1934 by Willard Harrison Bennett. Any electric current creates a

A potential solution to the confinement problem had been detailed in 1934 by Willard Harrison Bennett. Any electric current creates a

In 1950 Fuchs admitted to passing UK and U.S. atomic secrets to the USSR. As fusion devices generated high energy neutrons, which could be used to enrich nuclear fuel for bombs, the UK immediately classified all their fusion research. This meant the teams could no longer work in the open environment of the universities. The Imperial team under Ware moved to the AEI labs at Aldermaston and the Oxford team under Thonemann moved to Harwell.

By early 1952 there were numerous pinch devices in operation; Cousins and Ware had built several follow-on machines under the name Sceptre, and the Harwell team had built a series of ever-larger machines known as Mark I through Mark IV. In the U.S., Tuck built his

In 1950 Fuchs admitted to passing UK and U.S. atomic secrets to the USSR. As fusion devices generated high energy neutrons, which could be used to enrich nuclear fuel for bombs, the UK immediately classified all their fusion research. This meant the teams could no longer work in the open environment of the universities. The Imperial team under Ware moved to the AEI labs at Aldermaston and the Oxford team under Thonemann moved to Harwell.

By early 1952 there were numerous pinch devices in operation; Cousins and Ware had built several follow-on machines under the name Sceptre, and the Harwell team had built a series of ever-larger machines known as Mark I through Mark IV. In the U.S., Tuck built his

Early studies of the phenomenon suggested one solution to the problem was to increase the compression rate. In this approach, the compression would be started and stopped so rapidly that the bulk of the plasma would not have time to move; instead, a

Early studies of the phenomenon suggested one solution to the problem was to increase the compression rate. In this approach, the compression would be started and stopped so rapidly that the bulk of the plasma would not have time to move; instead, a

U.S. researchers planned to test both fast pinch and stabilised pinch by modifying their existing small-scale machines. In the UK, Thomson once again pressed for funding for a larger machine. This time he was much more warmly received, and initial funding of £200,000 was provided in late 1954. Design work continued during 1955, and in July the project was named ZETA. The term "zero energy" was a phrase used in the nuclear industry to refer to small

U.S. researchers planned to test both fast pinch and stabilised pinch by modifying their existing small-scale machines. In the UK, Thomson once again pressed for funding for a larger machine. This time he was much more warmly received, and initial funding of £200,000 was provided in late 1954. Design work continued during 1955, and in July the project was named ZETA. The term "zero energy" was a phrase used in the nuclear industry to refer to small

From 1953 the U.S. had increasingly concentrated on the fast pinch concept. Some of these machines had produced neutrons, and these were initially associated with fusion. There was so much excitement that several other researchers quickly entered the field as well. Among these was

From 1953 the U.S. had increasingly concentrated on the fast pinch concept. Some of these machines had produced neutrons, and these were initially associated with fusion. There was so much excitement that several other researchers quickly entered the field as well. Among these was

ZETA started operation in mid-August 1957, initially with hydrogen. These runs demonstrated that ZETA was not suffering from the same stability problems that earlier pinch machines had seen and their plasmas were lasting for milliseconds, up from microseconds, a full three

ZETA started operation in mid-August 1957, initially with hydrogen. These runs demonstrated that ZETA was not suffering from the same stability problems that earlier pinch machines had seen and their plasmas were lasting for milliseconds, up from microseconds, a full three

The news was too good to keep bottled up. Tantalising leaks started appearing in September. In October, Thonemann, Cockcroft and William P. Thompson hinted that interesting results would be following. In November a UKAEA spokesman noted "The indications are that fusion has been achieved". Based on these hints, the ''

The news was too good to keep bottled up. Tantalising leaks started appearing in September. In October, Thonemann, Cockcroft and William P. Thompson hinted that interesting results would be following. In November a UKAEA spokesman noted "The indications are that fusion has been achieved". Based on these hints, the ''

When the information-sharing agreement was signed in November a further benefit was realised: teams from the various labs were allowed to visit each other. The U.S. team, including Stirling Colgate, Lyman Spitzer, Jim Tuck and Arthur Edward Ruark, all visited ZETA and concluded there was a "major probability" the neutrons were from fusion.

On his return to the U.S., Spitzer calculated that something was wrong with the ZETA results. He noticed that the apparent temperature, 5 million K, would not have time to develop during the short firing times. ZETA did not discharge enough energy into the plasma to heat it to those temperatures so quickly. If the temperature was increasing at the relatively slow rate his calculations suggested, fusion would not be taking place early in the reaction, and could not be adding energy that might make up the difference. Spitzer suspected the temperature reading was not accurate. Since it was the temperature reading that suggested the neutrons were from fusion, if the temperature was lower, it implied the neutrons were non-fusion in origin.

Colgate had reached similar conclusions. In early 1958, he, Harold Furth and John Ferguson started an extensive study of the results from all known pinch machines. Instead of inferring temperature from neutron energy, they used the conductivity of the plasma itself, based on the well-understood relationships between temperature and conductivity. They concluded that the machines were producing temperatures perhaps what the neutrons were suggesting, nowhere near hot enough to explain the number of neutrons being produced, regardless of their energy.

By this time the latest versions of the US pinch devices, Perhapsatron S-3 and Columbus S-4, were producing neutrons of their own. The fusion research world reached a high point. In January, results from pinch experiments in the U.S. and UK both announced that neutrons were being released, and that fusion had apparently been achieved. The misgivings of Spitzer and Colgate were ignored.

When the information-sharing agreement was signed in November a further benefit was realised: teams from the various labs were allowed to visit each other. The U.S. team, including Stirling Colgate, Lyman Spitzer, Jim Tuck and Arthur Edward Ruark, all visited ZETA and concluded there was a "major probability" the neutrons were from fusion.

On his return to the U.S., Spitzer calculated that something was wrong with the ZETA results. He noticed that the apparent temperature, 5 million K, would not have time to develop during the short firing times. ZETA did not discharge enough energy into the plasma to heat it to those temperatures so quickly. If the temperature was increasing at the relatively slow rate his calculations suggested, fusion would not be taking place early in the reaction, and could not be adding energy that might make up the difference. Spitzer suspected the temperature reading was not accurate. Since it was the temperature reading that suggested the neutrons were from fusion, if the temperature was lower, it implied the neutrons were non-fusion in origin.

Colgate had reached similar conclusions. In early 1958, he, Harold Furth and John Ferguson started an extensive study of the results from all known pinch machines. Instead of inferring temperature from neutron energy, they used the conductivity of the plasma itself, based on the well-understood relationships between temperature and conductivity. They concluded that the machines were producing temperatures perhaps what the neutrons were suggesting, nowhere near hot enough to explain the number of neutrons being produced, regardless of their energy.

By this time the latest versions of the US pinch devices, Perhapsatron S-3 and Columbus S-4, were producing neutrons of their own. The fusion research world reached a high point. In January, results from pinch experiments in the U.S. and UK both announced that neutrons were being released, and that fusion had apparently been achieved. The misgivings of Spitzer and Colgate were ignored.

The long-planned release of fusion data was announced to the public in mid-January. Considerable material from the UK's ZETA and

The long-planned release of fusion data was announced to the public in mid-January. Considerable material from the UK's ZETA and

ZETA's failure was due to limited information; using the best available measurements, ZETA was returning several signals that suggested the neutrons were due to fusion. The original temperature measures were made by examining the Doppler shifting of the spectral lines of the atoms in the plasma. The inaccuracy of the measurement and spurious results caused by electron impacts with the container led to misleading measurements based on the impurities, not the plasma itself. Over the next decade, ZETA was used continuously in an effort to develop better diagnostic tools to resolve these problems.

This work eventually developed a method that is used to this day. The introduction of

ZETA's failure was due to limited information; using the best available measurements, ZETA was returning several signals that suggested the neutrons were due to fusion. The original temperature measures were made by examining the Doppler shifting of the spectral lines of the atoms in the plasma. The inaccuracy of the measurement and spurious results caused by electron impacts with the container led to misleading measurements based on the impurities, not the plasma itself. Over the next decade, ZETA was used continuously in an effort to develop better diagnostic tools to resolve these problems.

This work eventually developed a method that is used to this day. The introduction of

Britain's Sputnik

– BBC Radio 4 programme on ZETA first broadcast on 16 January 2008

ZETA – Peace Atoms

contemporary newsreel story on the reactor. * {{fusion experiments, state=collapsed Magnetic confinement fusion devices Nuclear power in the United Kingdom Nuclear research institutes in the United Kingdom Nuclear research reactors Nuclear technology in the United Kingdom Research institutes in Oxfordshire Vale of White Horse

ZETA, short for Zero Energy Thermonuclear Assembly, was a major experiment in the early history of

ZETA, short for Zero Energy Thermonuclear Assembly, was a major experiment in the early history of fusion power

Fusion power is a proposed form of power generation that would generate electricity by using heat from nuclear fusion reactions. In a fusion process, two lighter atomic nuclei combine to form a heavier nucleus, while releasing energy. Devices d ...

research. Based on the pinch plasma confinement technique, and built at the Atomic Energy Research Establishment

The Atomic Energy Research Establishment (AERE), also known as Harwell Laboratory, was the main Headquarters, centre for nuclear power, atomic energy research and development in the United Kingdom from 1946 to the 1990s. It was created, owned ...

in the United Kingdom, ZETA was larger and more powerful than any fusion machine in the world at that time. Its goal was to produce large numbers of fusion reactions, although it was not large enough to produce net energy.

ZETA went into operation in August 1957 and by the end of the month it was giving off bursts of about a million neutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , that has no electric charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. The Discovery of the neutron, neutron was discovered by James Chadwick in 1932, leading to the discovery of nucle ...

s per pulse. Measurements suggested the fuel was reaching between 1 and 5 million kelvin

The kelvin (symbol: K) is the base unit for temperature in the International System of Units (SI). The Kelvin scale is an absolute temperature scale that starts at the lowest possible temperature (absolute zero), taken to be 0 K. By de ...

s, a temperature that would produce nuclear fusion

Nuclear fusion is a nuclear reaction, reaction in which two or more atomic nuclei combine to form a larger nuclei, nuclei/neutrons, neutron by-products. The difference in mass between the reactants and products is manifested as either the rele ...

reactions, explaining the quantities of neutrons being seen. Early results were leaked to the press in September 1957, and the following January an extensive review was released. Front-page articles in newspapers around the world announced it as a breakthrough towards unlimited energy, a scientific advance for Britain greater than the recently launched Sputnik

Sputnik 1 (, , ''Satellite 1''), sometimes referred to as simply Sputnik, was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space progra ...

had been for the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

.

U.S. and Soviet experiments had also given off similar neutron bursts at temperatures that were not high enough for fusion. This led Lyman Spitzer

Lyman Spitzer Jr. (June 26, 1914 – March 31, 1997) was an American theoretical physicist, astronomer and mountaineer. As a scientist, he carried out research into star formation and plasma physics and in 1946 conceived the idea of telesco ...

to express his scepticism of the results, but his comments were dismissed by UK observers as jingoism

Jingoism is nationalism in the form of aggressive and proactive foreign policy, such as a country's advocacy for the use of threats or actual force, as opposed to peaceful relations, in efforts to safeguard what it perceives as its national inte ...

. Further experiments on ZETA showed that the original temperature measurements were misleading; the bulk temperature was too low for fusion reactions to create the number of neutrons being seen. The claim that ZETA had produced fusion had to be publicly withdrawn, an embarrassing event that cast a chill over the entire fusion establishment. The neutrons were later explained as being the product of instabilities in the fuel. These instabilities appeared inherent to any similar design, and work on the basic pinch concept as a road to fusion power ended by 1961.

Despite ZETA's failure to achieve fusion, the device went on to have a long experimental lifetime and produced numerous important advances in the field. In one line of development, the use of laser

A laser is a device that emits light through a process of optical amplification based on the stimulated emission of electromagnetic radiation. The word ''laser'' originated as an acronym for light amplification by stimulated emission of radi ...

s to more accurately measure the temperature was tested on ZETA, and was later used to confirm the results of the Soviet tokamak

A tokamak (; ) is a device which uses a powerful magnetic field generated by external magnets to confine plasma (physics), plasma in the shape of an axially symmetrical torus. The tokamak is one of several types of magnetic confinement fusi ...

approach. In another, while examining ZETA test runs it was noticed that the plasma self-stabilised after the power was turned off. This has led to the modern reversed field pinch

A reversed-field pinch (RFP) is a device used to produce and contain near-thermonuclear plasmas. It is a toroidal pinch that uses a unique magnetic field configuration as a scheme to magnetically confine a plasma, primarily to study magnetic ...

concept. More generally, studies of the instabilities in ZETA have led to several important theoretical advances that form the basis of modern plasma theory.

Conceptual development

The basic understanding ofnuclear fusion

Nuclear fusion is a nuclear reaction, reaction in which two or more atomic nuclei combine to form a larger nuclei, nuclei/neutrons, neutron by-products. The difference in mass between the reactants and products is manifested as either the rele ...

was developed during the 1920s as physicists explored the new science of quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental physical Scientific theory, theory that describes the behavior of matter and of light; its unusual characteristics typically occur at and below the scale of atoms. Reprinted, Addison-Wesley, 1989, It is ...

. George Gamow

George Gamow (sometimes Gammoff; born Georgiy Antonovich Gamov; ; 4 March 1904 – 19 August 1968) was a Soviet and American polymath, theoretical physicist and cosmologist. He was an early advocate and developer of Georges Lemaître's Big Ba ...

's 1928 exploration of quantum tunnelling

In physics, quantum tunnelling, barrier penetration, or simply tunnelling is a quantum mechanical phenomenon in which an object such as an electron or atom passes through a potential energy barrier that, according to classical mechanics, shoul ...

demonstrated that nuclear reactions could take place at lower energies than classical theory predicted. Using this theory, in 1929 Fritz Houtermans and Robert Atkinson demonstrated that expected reaction rates in the core of the Sun supported Arthur Eddington

Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington, (28 December 1882 – 22 November 1944) was an English astronomer, physicist, and mathematician. He was also a philosopher of science and a populariser of science. The Eddington limit, the natural limit to the lu ...

's 1920 suggestion that the Sun is powered by fusion.

In 1934, Mark Oliphant

Sir Marcus Laurence Elwin Oliphant, (8 October 1901 – 14 July 2000) was an Australian physicist and humanitarian who played an important role in the first experimental demonstration of nuclear fusion and in the development of nuclear weapon ...

, Paul Harteck

Paul Karl Maria Harteck (20 July 190222 January 1985) was an Austrian physical chemist. In 1945 under Operation Epsilon in "the big sweep" throughout Germany, Harteck was arrested by the allied British and American Armed Forces for suspicion of ...

and Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson (30 August 1871 – 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand physicist who was a pioneering researcher in both Atomic physics, atomic and nuclear physics. He has been described as "the father of nu ...

were the first to achieve fusion on Earth, using a particle accelerator

A particle accelerator is a machine that uses electromagnetic fields to propel electric charge, charged particles to very high speeds and energies to contain them in well-defined particle beam, beams. Small accelerators are used for fundamental ...

to shoot deuterium

Deuterium (hydrogen-2, symbol H or D, also known as heavy hydrogen) is one of two stable isotopes of hydrogen; the other is protium, or hydrogen-1, H. The deuterium nucleus (deuteron) contains one proton and one neutron, whereas the far more c ...

nuclei into a metal foil containing deuterium, lithium

Lithium (from , , ) is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Li and atomic number 3. It is a soft, silvery-white alkali metal. Under standard temperature and pressure, standard conditions, it is the least dense metal and the ...

or other elements. This allowed them to measure the nuclear cross section

The nuclear cross section of a nucleus is used to describe the probability that a nuclear reaction will occur. The concept of a nuclear cross section can be quantified physically in terms of "characteristic area" where a larger area means a larg ...

of various fusion reactions, and determined that the deuterium-deuterium reaction occurred at a lower energy than other reactions, peaking at about 100,000 electronvolt

In physics, an electronvolt (symbol eV), also written electron-volt and electron volt, is the measure of an amount of kinetic energy gained by a single electron accelerating through an Voltage, electric potential difference of one volt in vacuum ...

s (100 keV).

This energy corresponds to the average energy of particles in a gas heated to thousands of millions of kelvins. Materials heated beyond a few tens of thousands of kelvins dissociate into their electron

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary charge, elementary electric charge. It is a fundamental particle that comprises the ordinary matter that makes up the universe, along with up qua ...

s and nuclei, producing a gas-like state of matter

In physics, a state of matter is one of the distinct forms in which matter can exist. Four states of matter are observable in everyday life: solid, liquid, gas, and Plasma (physics), plasma.

Different states are distinguished by the ways the ...

known as plasma. In any gas the particles have a wide range of energies, normally following the Maxwell–Boltzmann statistics

In statistical mechanics, Maxwell–Boltzmann statistics describes the distribution of classical material particles over various energy states in thermal equilibrium. It is applicable when the temperature is high enough or the particle density ...

. In such a mixture, a small number of particles will have much higher energy than the bulk.

This leads to an interesting possibility: even at temperatures well below 100,000 eV, some particles will randomly have enough energy to undergo fusion. Those reactions release huge amounts of energy. If that energy can be captured back into the plasma, it can heat other particles to that energy as well, making the reaction self-sustaining. In 1944, Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian and naturalized American physicist, renowned for being the creator of the world's first artificial nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1, and a member of the Manhattan Project ...

calculated this would occur at about 50,000,000 K.

Confinement

Taking advantage of this possibility requires the fuel plasma to be held together long enough that these random reactions have time to occur. Like any hot gas, the plasma has an internalpressure

Pressure (symbol: ''p'' or ''P'') is the force applied perpendicular to the surface of an object per unit area over which that force is distributed. Gauge pressure (also spelled ''gage'' pressure)The preferred spelling varies by country and eve ...

and thus tends to expand according to the ideal gas law

The ideal gas law, also called the general gas equation, is the equation of state of a hypothetical ideal gas. It is a good approximation of the behavior of many gases under many conditions, although it has several limitations. It was first stat ...

. For a fusion reactor, the problem is keeping the plasma contained against this pressure; any known physical container would melt at these temperatures.

A plasma is electrically conductive, and is subject to electric and magnetic fields. In a magnetic field, the electrons and nuclei orbit the magnetic field lines. A simple confinement system is a plasma-filled tube placed inside the open core of a solenoid

upright=1.20, An illustration of a solenoid

upright=1.20, Magnetic field created by a seven-loop solenoid (cross-sectional view) described using field lines

A solenoid () is a type of electromagnet formed by a helix, helical coil of wire whos ...

. The plasma naturally wants to expand outwards to the walls of the tube, as well as move along it, towards the ends. The solenoid creates a magnetic field running down the centre of the tube, which the particles will orbit, preventing their motion towards the sides. Unfortunately, this arrangement does not confine the plasma along the length of the tube, and the plasma is free to flow out the ends.

The obvious solution to this problem is to bend the tube around into a torus

In geometry, a torus (: tori or toruses) is a surface of revolution generated by revolving a circle in three-dimensional space one full revolution about an axis that is coplanarity, coplanar with the circle. The main types of toruses inclu ...

(a ring or doughnut shape). Motion towards the sides remains constrained as before, and while the particles remain free to move along the lines, in this case, they will simply circulate around the long axis of the tube. But, as Fermi pointed out, when the solenoid is bent into a ring, the electrical windings would be closer together on the inside than the outside. This would lead to an uneven field across the tube, and the fuel will slowly drift out of the centre. Some additional force needs to counteract this drift, providing long-term confinement.

Pinch concept

A potential solution to the confinement problem had been detailed in 1934 by Willard Harrison Bennett. Any electric current creates a

A potential solution to the confinement problem had been detailed in 1934 by Willard Harrison Bennett. Any electric current creates a magnetic field

A magnetic field (sometimes called B-field) is a physical field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular ...

, and due to the Lorentz force

In electromagnetism, the Lorentz force is the force exerted on a charged particle by electric and magnetic fields. It determines how charged particles move in electromagnetic environments and underlies many physical phenomena, from the operation ...

, this causes an inward directed force. This was first noticed in lightning rod

A lightning rod or lightning conductor (British English) is a metal rod mounted on a structure and intended to protect the structure from a lightning strike. If lightning hits the structure, it is most likely to strike the rod and be conducted ...

s. Bennett showed that the same effect would cause a current to "self-focus" a plasma into a thin column. A second paper by Lewi Tonks

Lewi Tonks (1897–July 30, 1971) was an American physicist who worked for General Electric on microwaves, plasma physics and nuclear reactors. Under Irving Langmuir, his work pioneered the study of plasma oscillations. He is also noted for the n ...

in 1937 considered the issue again, introducing the name " pinch effect". It was followed by a paper by Tonks and William Allis.

Applying a pinch current in a plasma can be used to counteract expansion and confine the plasma. A simple way to do this is to put the plasma in a linear tube and pass a current through it using electrode

An electrode is an electrical conductor used to make contact with a nonmetallic part of a circuit (e.g. a semiconductor, an electrolyte, a vacuum or a gas). In electrochemical cells, electrodes are essential parts that can consist of a varie ...

s at either end, like a fluorescent lamp

A fluorescent lamp, or fluorescent tube, is a low-pressure mercury-vapor gas-discharge lamp that uses fluorescence to produce visible light. An electric current in the gas excites mercury vapor, to produce ultraviolet and make a phosphor ...

. This arrangement still produces no confinement along the length of the tube, so the plasma flows onto the electrodes, rapidly eroding them. This is not a problem for a purely experimental machine, and there are ways to reduce the rate. Another solution is to place a magnet next to the tube; when the magnetic field changes, the fluctuations cause an electric current to be induced in the plasma. The major advantage of this arrangement is that there are no physical objects within the tube, so it can be formed into a torus and allow the plasma to circulate freely.

The toroidal pinch concept as a route to fusion was explored in the UK during the mid-1940s, especially by George Paget Thomson

Sir George Paget Thomson (; 3 May 1892 – 10 September 1975) was an English physicist who shared the 1937 Nobel Prize in Physics with Clinton Davisson “for their experimental discovery of the diffraction of electrons by crystals”.

Educa ...

of Imperial College London

Imperial College London, also known as Imperial, is a Public university, public research university in London, England. Its history began with Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Prince Albert, husband of Queen Victoria, who envisioned a Al ...

. With the formation of the Atomic Energy Research Establishment

The Atomic Energy Research Establishment (AERE), also known as Harwell Laboratory, was the main Headquarters, centre for nuclear power, atomic energy research and development in the United Kingdom from 1946 to the 1990s. It was created, owned ...

(AERE) at Harwell, Oxfordshire

Harwell is a village and civil parish in the Vale of White Horse about west of Didcot, east of Wantage and south of Oxford, England. The parish measures about north – south, and almost east – west at its widest point. In 1923, its area ...

, in 1945, Thomson repeatedly petitioned the director, John Cockcroft

Sir John Douglas Cockcroft (27 May 1897 – 18 September 1967) was an English nuclear physicist who shared the 1951 Nobel Prize in Physics with Ernest Walton for their splitting of the atomic nucleus, which was instrumental in the developmen ...

, for funds to develop an experimental machine. These requests were turned down. At the time there was no obvious military use, so the concept was left unclassified. This allowed Thomson and Moses Blackman to file a patent on the idea in 1946, describing a device using just enough pinch current to ionise and briefly confine the plasma while being heated by a microwave

Microwave is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths shorter than other radio waves but longer than infrared waves. Its wavelength ranges from about one meter to one millimeter, corresponding to frequency, frequencies between 300&n ...

source that would also continually drive the current.

As a practical device there is an additional requirement, that the reaction conditions last long enough to burn a reasonable amount of the fuel. In the original Thomson and Blackman design, it was the job of the microwave injection to drive the electrons to maintain the current and produce pinches that lasted on the order of one minute, allowing the plasma to reach 500 million K. The current in the plasma also heated it; if the current was also used as the heat source, the only limit to the heating was the power of the pulse. This led to a new reactor design where the system operated in brief but very powerful pulses. Such a machine would demand a very large power supply.

First machines

In 1947, Cockcroft arranged a meeting of several Harwell physicists to study Thomson's latest concepts, including Harwell's director of theoretical physics,Klaus Fuchs

Klaus Emil Julius Fuchs (29 December 1911 – 28 January 1988) was a German theoretical physicist and atomic spy who supplied information from the American, British, and Canadian Manhattan Project to the Soviet Union during and shortly a ...

. Thomson's concepts were poorly received, especially by Fuchs. When this presentation also failed to gain funding, Thomson passed along his concepts to two graduate students at Imperial, Stanley (Stan) W. Cousins and Alan Alfred Ware (1924-2010). He added a report on a type of toroidal particle accelerator known as the "Wirbelrohr" ("whirl tube"), designed in Germany by Max Steenbeck

Max Christian Theodor Steenbeck (21 March 1904 – 15 December 1981) was a German nuclear physicist who invented the betatron in 1934 during his employment at the Siemens AG.

After the World War II, Steenbeck was taken into the Soviet custo ...

. The Wirbelrohr consisted of a transformer

In electrical engineering, a transformer is a passive component that transfers electrical energy from one electrical circuit to another circuit, or multiple Electrical network, circuits. A varying current in any coil of the transformer produces ...

with a torus-shaped vacuum tube as its secondary coil, similar in concept to the toroidal pinch devices.

Later that year, Ware built a small machine out of old radar equipment and was able to induce powerful currents. When they did, the plasma gave off flashes of light, but he could not devise a way to measure the temperature of the plasma. Thomson continued to pressure the government to allow him to build a full-scale device, using his considerable political currency to argue for the creation of a dedicated experimental station at the Associated Electrical Industries

Associated Electrical Industries (AEI) was a British holding company formed in 1928 through the merger of British Thomson-Houston (BTH) and Metropolitan-Vickers electrical engineering companies. In 1967 AEI was acquired by GEC, to create the UK ...

(AEI) lab that had recently been constructed at Aldermaston

Aldermaston ( ) is a village and civil parish in Berkshire, England. In the 2011 census, the parish had a population of 1,015. The village is in the Kennet Valley and bounds Hampshire to the south. It is approximately from Newbury, Basin ...

.

Ware discussed the experiments with anyone who was interested, including Jim Tuck of Clarendon Laboratory

The Clarendon Laboratory, located on Parks Road within the Science Area in Oxford, England (not to be confused with the Clarendon Building, also in Oxford), is part of the Department of Physics at Oxford University. It houses the atomic and la ...

at Oxford University

The University of Oxford is a collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the second-oldest continuously operating u ...

. While working at Los Alamos during the war, Tuck and Stanislaw Ulam Stanislav and variants may refer to:

People

*Stanislav (given name), a Slavic given name with many spelling variations (Stanislaus, Stanislas, Stanisław, etc.)

Places

* Stanislav, Kherson Oblast, a coastal village in Ukraine

* Stanislaus County, ...

had built an unsuccessful fusion system using shaped charge

A shaped charge, commonly also hollow charge if shaped with a cavity, is an explosive charge shaped to focus the effect of the explosive's energy. Different types of shaped charges are used for various purposes such as cutting and forming metal, ...

explosives, but it did not work. Tuck was joined by Australian Peter Thonemann, who had worked on fusion theory, and the two arranged funding through Clarendon to build a small device like the one at Imperial. But before this work started, Tuck was offered a job in the U.S., eventually returning to Los Alamos.

Thonemann continued working on the idea and began a rigorous programme to explore the basic physics of plasmas in a magnetic field. Starting with linear tubes and mercury gas, he found that the current tended to expand outward through the plasma until it touched the walls of the container (see skin effect

In electromagnetism, skin effect is the tendency of an alternating current, alternating electric current (AC) to become distributed within a Conductor (material), conductor such that the current density is largest near the surface of the conduc ...

). He countered this with the addition of small electromagnets outside the tube, which pushed back against the current and kept it centred. By 1949, he had moved on from the glass tubes to a larger copper torus, in which he was able to demonstrate a stable pinched plasma. Frederick Lindemann

Frederick Alexander Lindemann, 1st Viscount Cherwell, ( ; 5 April 18863 July 1957) was a British physicist who was prime scientific adviser to Winston Churchill in World War II.

He was involved in the development of radar and infra-red guidan ...

and Cockcroft visited and were duly impressed.

Cockcroft asked Herbert Skinner to review the concepts, which he did in April 1948. He was sceptical of Thomson's ideas for creating a current in the plasma and thought Thonemann's ideas seemed more likely to work. He also pointed out that the behaviour of plasmas in a magnetic field was not well understood, and that "it is useless to do much further planning before this doubt is resolved."

Meanwhile, at Los Alamos, Tuck acquainted the U.S. researchers with the British efforts. In early 1951, Lyman Spitzer

Lyman Spitzer Jr. (June 26, 1914 – March 31, 1997) was an American theoretical physicist, astronomer and mountaineer. As a scientist, he carried out research into star formation and plasma physics and in 1946 conceived the idea of telesco ...

introduced his stellarator

A stellarator confines Plasma (physics), plasma using external magnets. Scientists aim to use stellarators to generate fusion power. It is one of many types of magnetic confinement fusion devices. The name "stellarator" refers to stars because ...

concept and was shopping the idea around the nuclear establishment looking for funding. Tuck was sceptical of Spitzer's enthusiasm and felt his development programme was "incredibly ambitious". He proposed a much less aggressive programme based on pinch. Both men presented their ideas in Washington in May 1951, which resulted in the Atomic Energy Commission giving Spitzer US$50,000. Tuck convinced Norris Bradbury

Norris Edwin Bradbury (May 30, 1909 – August 20, 1997) was an American physicist who served as director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory for 25 years from 1945 to 1970. He succeeded Robert Oppenheimer, who personally chose Bradbury ...

, the director of Los Alamos, to give him US$50,000 from the discretionary budget, using it to build the Perhapsatron

The Perhapsatron was an early fusion power device based on the pinch concept in the 1950s. Conceived by James (Jim) Tuck while working at Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), he whimsically named the device on the chance that it might, ''perhap ...

.

Early results

In 1950 Fuchs admitted to passing UK and U.S. atomic secrets to the USSR. As fusion devices generated high energy neutrons, which could be used to enrich nuclear fuel for bombs, the UK immediately classified all their fusion research. This meant the teams could no longer work in the open environment of the universities. The Imperial team under Ware moved to the AEI labs at Aldermaston and the Oxford team under Thonemann moved to Harwell.

By early 1952 there were numerous pinch devices in operation; Cousins and Ware had built several follow-on machines under the name Sceptre, and the Harwell team had built a series of ever-larger machines known as Mark I through Mark IV. In the U.S., Tuck built his

In 1950 Fuchs admitted to passing UK and U.S. atomic secrets to the USSR. As fusion devices generated high energy neutrons, which could be used to enrich nuclear fuel for bombs, the UK immediately classified all their fusion research. This meant the teams could no longer work in the open environment of the universities. The Imperial team under Ware moved to the AEI labs at Aldermaston and the Oxford team under Thonemann moved to Harwell.

By early 1952 there were numerous pinch devices in operation; Cousins and Ware had built several follow-on machines under the name Sceptre, and the Harwell team had built a series of ever-larger machines known as Mark I through Mark IV. In the U.S., Tuck built his Perhapsatron

The Perhapsatron was an early fusion power device based on the pinch concept in the 1950s. Conceived by James (Jim) Tuck while working at Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), he whimsically named the device on the chance that it might, ''perhap ...

in January 1952. It was later learned that Fuchs had passed the UK work to the Soviets, and that they had started a fusion programme as well.

It was clear to all of these groups that something was seriously wrong in the pinch machines. As the current was applied, the plasma column inside the vacuum tube would become unstable and break up, ruining the compression. Further work identified two types of instabilities, nicknamed "kink" and "sausage". In the kink, the normally toroidal plasma would bend to the sides, eventually touching the edges of the vessel. In the sausage, the plasma would neck down at locations along the plasma column to form a pattern similar to a link of sausages.

Investigations demonstrated both were caused by the same underlying mechanism. When the pinch current was applied, any area of the gas that had a slightly higher density would create a slightly stronger magnetic field and collapse faster than the surrounding gas. This caused the localised area to have higher density, which created an even stronger pinch, and a runaway reaction would follow. The quick collapse in a single area would cause the whole column to break up.

Stabilised pinch

Early studies of the phenomenon suggested one solution to the problem was to increase the compression rate. In this approach, the compression would be started and stopped so rapidly that the bulk of the plasma would not have time to move; instead, a

Early studies of the phenomenon suggested one solution to the problem was to increase the compression rate. In this approach, the compression would be started and stopped so rapidly that the bulk of the plasma would not have time to move; instead, a shock wave

In physics, a shock wave (also spelled shockwave), or shock, is a type of propagating disturbance that moves faster than the local speed of sound in the medium. Like an ordinary wave, a shock wave carries energy and can propagate through a me ...

created by this rapid compression would be responsible for compressing the majority of the plasma. This approach became known as ''fast pinch''. The Los Alamos team working on the Columbus linear machine designed an updated version to test this theory.

Others started looking for ways to stabilise the plasma during compression, and by 1953 two concepts had come to the fore. One solution was to wrap the vacuum tube in a sheet of thin but highly conductive metal. If the plasma column began to move, the current in the plasma would induce a magnetic field in the sheet, one that, due to Lenz's law

Lenz's law states that the direction of the electric current Electromagnetic induction, induced in a Electrical conductor, conductor by a changing magnetic field is such that the magnetic field created by the induced current opposes changes in t ...

, would push back against the plasma. This was most effective against large, slow movements, like the entire plasma torus drifting within the chamber.

The second solution used additional electromagnets wrapped around the vacuum tube. The magnetic fields from these magnets mixed with the pinch field created by the current in the plasma. The result was that the paths of the particles within the plasma tube were no longer purely circular around the torus, but twisted like the stripes on a barber's pole

A barber's pole is a type of Signage, sign used by barbers to signify the place or shop where they perform their craft. The trade sign is, by a tradition dating back to the Middle Ages, a staff or :wikt:pole, pole with a helix of colored Strip ...

. In the U.S., this concept was known as giving the plasma a "backbone", suppressing small-scale, localised instabilities. Calculations showed that this ''stabilised pinch'' would dramatically improve confinement times, and the older concepts "suddenly seemed obsolete".

Marshall Rosenbluth

Marshall Nicholas Rosenbluth (5 February 1927 – 28 September 2003) was an American plasma physicist and member of the National Academy of Sciences, and member of the American Philosophical Society. In 1997 he was awarded the National Medal of ...

, recently arrived at Los Alamos, began a detailed theoretical study of the pinch concept. With his wife Arianna W. Rosenbluth and Richard Garwin

Richard Lawrence Garwin (April 19, 1928 – May 13, 2025) was an American physicist and government advisor, best known as the author of the first hydrogen bomb design.

In 1978, Garwin was elected a member of the National Academy of Engineering ...

, he developed "motor theory", or "M-theory", published in 1954. The theory predicted that the heating effect of the electric current was greatly increased with the power of the electric field. This suggested that the fast pinch concept would be more likely to succeed, as it was easier to produce larger currents in these devices. When he incorporated the idea of stabilising magnets into the theory a second phenomenon appeared; for a particular, and narrow, set of conditions based on the physical size of the reactor, the power of the stabilising magnets and the amount of pinch, toroidal machines appeared to be naturally stable.

ZETA begins construction

U.S. researchers planned to test both fast pinch and stabilised pinch by modifying their existing small-scale machines. In the UK, Thomson once again pressed for funding for a larger machine. This time he was much more warmly received, and initial funding of £200,000 was provided in late 1954. Design work continued during 1955, and in July the project was named ZETA. The term "zero energy" was a phrase used in the nuclear industry to refer to small

U.S. researchers planned to test both fast pinch and stabilised pinch by modifying their existing small-scale machines. In the UK, Thomson once again pressed for funding for a larger machine. This time he was much more warmly received, and initial funding of £200,000 was provided in late 1954. Design work continued during 1955, and in July the project was named ZETA. The term "zero energy" was a phrase used in the nuclear industry to refer to small research reactor

Research reactors are nuclear fission-based nuclear reactors that serve primarily as a neutron source. They are also called non-power reactors, in contrast to power reactors that are used for electricity production, heat generation, or maritim ...

s, like ZEEP, which had a role similar to ZETA's goal of producing reactions while releasing no net energy.

The ZETA design was finalised in early 1956. Metropolitan-Vickers

Metropolitan-Vickers, Metrovick, or Metrovicks, was a British heavy electrical engineering company of the early-to-mid 20th century formerly known as British Westinghouse. Highly diversified, it was particularly well known for its industrial el ...

was hired to build the machine, which included a 150 tonne pulse transformer, the largest built in Britain to that point. A serious issue arose when the required high-strength steels needed for the electrical components were in short supply, but a strike in the U.S. electrical industry caused a sudden glut of material, resolving the problem.

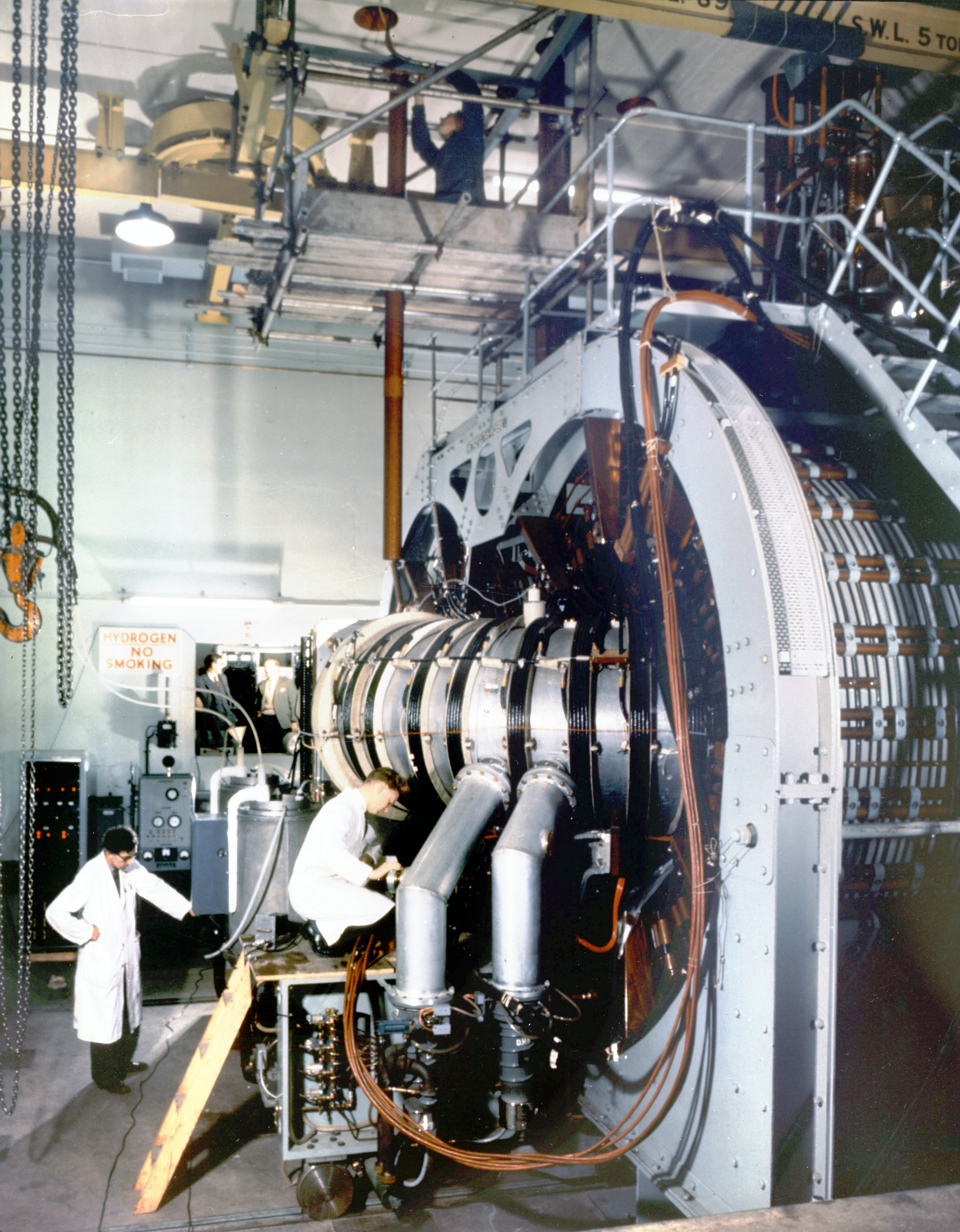

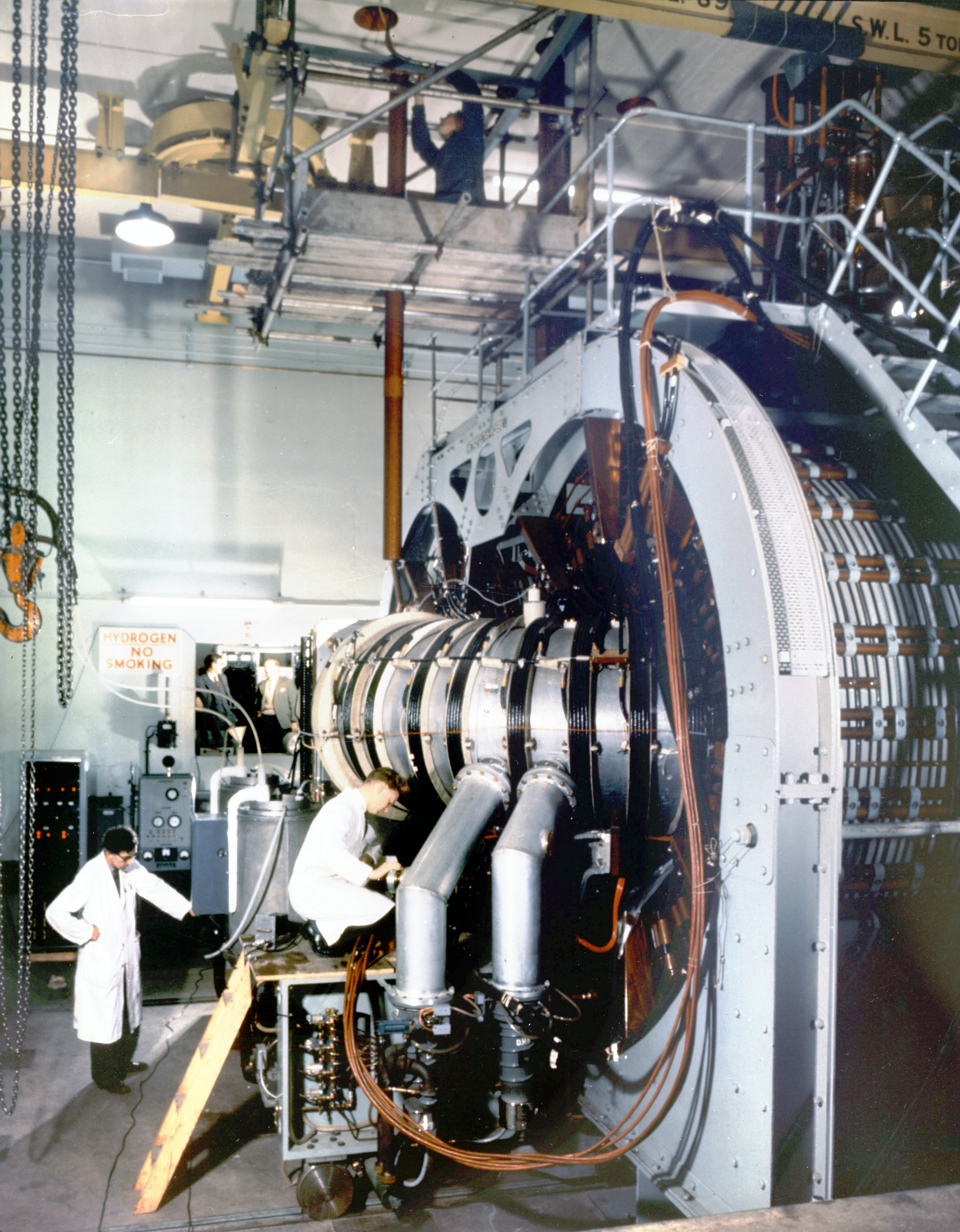

ZETA was the largest and most powerful fusion device in the world at the time of its construction. Its aluminium torus had an internal bore of and a major radius of , over three times the size of any machine built to date. It was also the most powerful design, incorporating an induction magnet that was designed to induce currents up to 100,000 amperes (amps) into the plasma. Later amendments to the design increased this to 200,000 amps. It included both types of stabilisation; its aluminium walls acted as the metal shield, and a series of secondary magnets ringed the torus. Windows placed in the gaps between the toroidal magnets allowed direct inspection of the plasma.

In July 1954, the AERE was reorganised into the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority

The United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority is a UK government research organisation responsible for the development of fusion energy. It is an executive non-departmental public body of the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ).

T ...

(UKAEA). Modifications to Harwell's Hangar 7 in order to house the machine began that year. Despite its advanced design, the price tag was modest: about US$1 million. By late 1956 it was clear that ZETA was going to come online in mid-1957, beating the Model C stellarator

The Model C stellarator was the first large-scale stellarator to be built, during the early stages of fusion power research. Planned since 1952, construction began in 1961 at what is today the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL). The Mo ...

and the newest versions of the Perhapsatron and Columbus. Because these projects were secret, based on the little information available the press concluded they were versions of the same conceptual device, and that the British were far ahead in the race to produce a working machine.

Soviet visit and the push to declassify

From 1953 the U.S. had increasingly concentrated on the fast pinch concept. Some of these machines had produced neutrons, and these were initially associated with fusion. There was so much excitement that several other researchers quickly entered the field as well. Among these was

From 1953 the U.S. had increasingly concentrated on the fast pinch concept. Some of these machines had produced neutrons, and these were initially associated with fusion. There was so much excitement that several other researchers quickly entered the field as well. Among these was Stirling Colgate

Stirling Auchincloss Colgate (; November 14, 1925 – December 1, 2013) was an American nuclear physicist at the Los Alamos National Laboratory and a professor emeritus of physics at the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology from 1965 to ...

, but his experiments quickly led him to conclude that fusion was not taking place. According to Spitzer resistivity, the temperature of the plasma could be determined from the current flowing through it. When Colgate performed the calculation, the temperatures in the plasma were far below the requirements for fusion.

This being the case, some other effect had to be creating the neutrons. Further work demonstrated that these were the result of instabilities in the fuel. The localised areas of high magnetic field acted as tiny particle accelerators, causing reactions that ejected neutrons. Modifications attempting to reduce these instabilities failed to improve the situation and by 1956 the fast pinch concept had largely been abandoned. The U.S. labs began turning their attention to the stabilised pinch concept, but by this time ZETA was almost complete and the US was well behind.

In 1956, while planning a well publicised state visit

A state visit is a formal visit by the head of state, head of a sovereign state, sovereign country (or Governor-general, representative of the head of a sovereign country) to another sovereign country, at the invitation of the head of state (or ...

by Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

and Nikolai Bulganin

Nikolai Alexandrovich Bulganin (; – 24 February 1975) was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 1955 to 1958. He also served as Minister of Defense (Soviet Union), Minister of Defense, following service in the Red Army during World War II.

...

to the UK, the Harwell researchers received an offer from Soviet scientist Igor Kurchatov

Igor Vasilyevich Kurchatov (; 12 January 1903 – 7 February 1960), was a Soviet physicist who played a central role in organizing and directing the former Soviet program of nuclear weapons, and has been referred to as "father of the Russian ...

to give a talk. They were surprised when he began his talk on "the possibility of producing thermonuclear reactions in a gaseous discharge". Kurchatov's speech revealed the Soviet efforts to produce fast pinch devices similar to the American designs, and their problems with instabilities in the plasmas. Kurchatov noted that they had also seen neutrons being released, and had initially believed them to be from fusion. But as they examined the numbers, it became clear the plasma was not hot enough and they concluded the neutrons were from other interactions.

Kurchatov's speech made it apparent that the three countries were all working on the same basic concepts and had all encountered the same sorts of problems. Cockcroft missed Kurchatov's visit because he had left for the U.S. to press for declassification of the fusion work to avoid this duplication of effort. There was a widespread belief on both sides of the Atlantic that sharing their findings would greatly improve progress. Now that it was known the Soviets were at the same basic development level, and that they were interested in talking about it publicly, the US and UK began considering releasing much of their information as well. This developed into a wider effort to release all fusion research at the second Atoms for Peace

"Atoms for Peace" was the title of a speech delivered by U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower to the UN General Assembly in New York City on December 8, 1953.

The United States then launched an "Atoms for Peace" program that supplied equipment ...

conference in Geneva in September 1958.

In June 1957 the UK and U.S. finalised their agreement to release data to each other sometime prior to the conference, which both the UK and the U.S. planned on attending "in force". The final terms were reached on 27 November 1957, opening the projects to mutual inspection, and calling for a wide public release of all the data in January 1958.

Promising results

ZETA started operation in mid-August 1957, initially with hydrogen. These runs demonstrated that ZETA was not suffering from the same stability problems that earlier pinch machines had seen and their plasmas were lasting for milliseconds, up from microseconds, a full three

ZETA started operation in mid-August 1957, initially with hydrogen. These runs demonstrated that ZETA was not suffering from the same stability problems that earlier pinch machines had seen and their plasmas were lasting for milliseconds, up from microseconds, a full three orders of magnitude

In a ratio scale based on powers of ten, the order of magnitude is a measure of the nearness of two figures. Two numbers are "within an order of magnitude" of each other if their ratio is between 1/10 and 10. In other words, the two numbers are wi ...

improvement. The length of the pulses allowed the plasma temperature to be measured using spectrographic

In chemical analysis, chromatography is a laboratory technique for the separation of a mixture into its components. The mixture is dissolved in a fluid solvent (gas or liquid) called the ''mobile phase'', which carries it through a system ...

means; although the light emitted was broadband, the Doppler shifting of the spectral lines of slight impurities in the gas (oxygen in particular) led to calculable temperatures.

Even in early experimental runs, the team started introducing deuterium gas into the mix and began increasing the current to 200,000 amps. On the evening of 30 August the machine produced huge numbers of neutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , that has no electric charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. The Discovery of the neutron, neutron was discovered by James Chadwick in 1932, leading to the discovery of nucle ...

s, on the order of one million per experimental pulse, or "shot". An effort to duplicate the results and eliminate possible measurement failure followed.

Much depended on the temperature of the plasma; if the temperature was low, the neutrons would not be fusion related. Spectrographic measurements suggested plasma temperatures between 1 and 5 million K; at those temperatures the predicted rate of fusion was within a factor of two of the number of neutrons being seen. It appeared that ZETA had reached the long-sought goal of producing small numbers of fusion reactions, as it was designed to do.

U.S. efforts had suffered a string of minor technical setbacks that delayed their experiments by about a year; both the new Perhapsatron S-3 and Columbus II did not start operating until around the same time as ZETA in spite of being much smaller experiments. Nevertheless, as these experiments came online in mid-1957, they too began generating neutrons. By September, both these machines and a new design, DCX at Oak Ridge National Laboratory

Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) is a federally funded research and development centers, federally funded research and development center in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, United States. Founded in 1943, the laboratory is sponsored by the United Sta ...

, appeared so promising that Edward Gardner reported that:

Prestige politics

The news was too good to keep bottled up. Tantalising leaks started appearing in September. In October, Thonemann, Cockcroft and William P. Thompson hinted that interesting results would be following. In November a UKAEA spokesman noted "The indications are that fusion has been achieved". Based on these hints, the ''

The news was too good to keep bottled up. Tantalising leaks started appearing in September. In October, Thonemann, Cockcroft and William P. Thompson hinted that interesting results would be following. In November a UKAEA spokesman noted "The indications are that fusion has been achieved". Based on these hints, the ''Financial Times

The ''Financial Times'' (''FT'') is a British daily newspaper printed in broadsheet and also published digitally that focuses on business and economic Current affairs (news format), current affairs. Based in London, the paper is owned by a Jap ...

'' dedicated an entire two-column article to the issue. Between then and early 1958, the British press published an average of two articles a week on ZETA. Even the U.S. papers picked up the story; on 17 November ''The New York Times'' reported on the hints of success.

Although the British and the U.S. had agreed to release their data in full, at this point the overall director of the U.S. program, Lewis Strauss

Lewis Lichtenstein Strauss ( ; January 31, 1896January 21, 1974) was an American government official, businessman, philanthropist, and naval officer. He was one of the original members of the United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) in 1946 ...

, decided to hold back the release. Tuck argued that the field looked so promising that it would be premature to release any data before the researchers knew that fusion was definitely taking place. Strauss agreed, and announced that they would withhold their data for a period to check their results.

As the matter became better known in the press, on 26 November the publication issue was raised in House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

. Responding to a question by the opposition, the leader of the house announced the results publicly while explaining the delay in publication due to the UK–U.S. agreement. The UK press interpreted this differently, claiming that the U.S. was dragging its feet because it was unable to replicate the British results.

Things came to a head on 12 December when a former member of parliament, Anthony Nutting, wrote a ''New York Herald Tribune

The ''New York Herald Tribune'' was a newspaper published between 1924 and 1966. It was created in 1924 when Ogden Mills Reid of the '' New York Tribune'' acquired the '' New York Herald''. It was regarded as a "writer's newspaper" and compet ...

'' article claiming:

The article resulted in a flurry of activity in the Macmillan administration. Having originally planned to release their results at a scheduled meeting of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, there was great concern over whether to invite the Americans and Soviets, especially as they believed the Americans would be greatly upset if the Soviets arrived, but just as upset if they were not invited and the event was all-British. The affair eventually led to the UKAEA making a public announcement that the U.S. was not holding back the ZETA results, but this infuriated the local press, which continued to claim the U.S. was delaying to allow them to catch up.

Early concerns

When the information-sharing agreement was signed in November a further benefit was realised: teams from the various labs were allowed to visit each other. The U.S. team, including Stirling Colgate, Lyman Spitzer, Jim Tuck and Arthur Edward Ruark, all visited ZETA and concluded there was a "major probability" the neutrons were from fusion.

On his return to the U.S., Spitzer calculated that something was wrong with the ZETA results. He noticed that the apparent temperature, 5 million K, would not have time to develop during the short firing times. ZETA did not discharge enough energy into the plasma to heat it to those temperatures so quickly. If the temperature was increasing at the relatively slow rate his calculations suggested, fusion would not be taking place early in the reaction, and could not be adding energy that might make up the difference. Spitzer suspected the temperature reading was not accurate. Since it was the temperature reading that suggested the neutrons were from fusion, if the temperature was lower, it implied the neutrons were non-fusion in origin.

Colgate had reached similar conclusions. In early 1958, he, Harold Furth and John Ferguson started an extensive study of the results from all known pinch machines. Instead of inferring temperature from neutron energy, they used the conductivity of the plasma itself, based on the well-understood relationships between temperature and conductivity. They concluded that the machines were producing temperatures perhaps what the neutrons were suggesting, nowhere near hot enough to explain the number of neutrons being produced, regardless of their energy.

By this time the latest versions of the US pinch devices, Perhapsatron S-3 and Columbus S-4, were producing neutrons of their own. The fusion research world reached a high point. In January, results from pinch experiments in the U.S. and UK both announced that neutrons were being released, and that fusion had apparently been achieved. The misgivings of Spitzer and Colgate were ignored.

When the information-sharing agreement was signed in November a further benefit was realised: teams from the various labs were allowed to visit each other. The U.S. team, including Stirling Colgate, Lyman Spitzer, Jim Tuck and Arthur Edward Ruark, all visited ZETA and concluded there was a "major probability" the neutrons were from fusion.

On his return to the U.S., Spitzer calculated that something was wrong with the ZETA results. He noticed that the apparent temperature, 5 million K, would not have time to develop during the short firing times. ZETA did not discharge enough energy into the plasma to heat it to those temperatures so quickly. If the temperature was increasing at the relatively slow rate his calculations suggested, fusion would not be taking place early in the reaction, and could not be adding energy that might make up the difference. Spitzer suspected the temperature reading was not accurate. Since it was the temperature reading that suggested the neutrons were from fusion, if the temperature was lower, it implied the neutrons were non-fusion in origin.

Colgate had reached similar conclusions. In early 1958, he, Harold Furth and John Ferguson started an extensive study of the results from all known pinch machines. Instead of inferring temperature from neutron energy, they used the conductivity of the plasma itself, based on the well-understood relationships between temperature and conductivity. They concluded that the machines were producing temperatures perhaps what the neutrons were suggesting, nowhere near hot enough to explain the number of neutrons being produced, regardless of their energy.

By this time the latest versions of the US pinch devices, Perhapsatron S-3 and Columbus S-4, were producing neutrons of their own. The fusion research world reached a high point. In January, results from pinch experiments in the U.S. and UK both announced that neutrons were being released, and that fusion had apparently been achieved. The misgivings of Spitzer and Colgate were ignored.

Public release, worldwide interest

The long-planned release of fusion data was announced to the public in mid-January. Considerable material from the UK's ZETA and

The long-planned release of fusion data was announced to the public in mid-January. Considerable material from the UK's ZETA and Sceptre

A sceptre (or scepter in American English) is a Staff of office, staff or wand held in the hand by a ruling monarch as an item of regalia, royal or imperial insignia, signifying Sovereignty, sovereign authority.

Antiquity

Ancient Egypt and M ...

devices was released in depth in the 25 January 1958 edition of ''Nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

'', which also included results from Los Alamos' Perhapsatron S-3, Columbus II and Columbus S-2. The UK press was livid. ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. First published in 1791, it is the world's oldest Sunday newspaper.

In 1993 it was acquired by Guardian Media Group Limited, and operated as a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' ...

'' wrote that "Admiral Strauss' tactics have soured what should be an exciting announcement of scientific progress so that it has become a sordid episode of prestige politics."

The results were typical of the normally sober scientific language, and although the neutrons were noted, there were no strong claims as to their source. The day before the release, Cockcroft, the overall director at Harwell, called a press conference

A press conference, also called news conference or press briefing, is a media event in which notable individuals or organizations invite journalism, journalists to hear them speak and ask questions. Press conferences are often held by politicia ...

to introduce the British press to the results. Some indication of the importance of the event can be seen in the presence of a BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

television field crew, a rare occurrence at that time. He began by introducing the fusion programme and the ZETA machine, and then noted:

The reporters at the meeting were not satisfied with this assessment and continued to press Cockcroft on the neutron issue. After being asked several times, he eventually stated that in his opinion, he was "90 percent certain" they were from fusion. This was unwise; a statement of opinion from a Nobel prize winner was taken as a statement of fact. The next day, the Sunday newspapers were covered with the news that fusion had been achieved in ZETA, often with claims about how the UK was now far in the lead in fusion research. Cockcroft further hyped the results on television following the release, stating: "To Britain this discovery is greater than the Russian Sputnik."

As planned, the U.S. also released a large batch of results from their smaller pinch machines. Many of them were also giving off neutrons, although ZETA was stabilised for much longer periods and generating more neutrons, by a factor of about 1000. When questioned about the success in the UK, Strauss denied that the U.S. was behind in the fusion race. When reporting on the topic, ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' chose to focus on Los Alamos' Columbus II, only mentioning ZETA later in the article, and then concluded the two countries were "neck and neck." Other reports from the U.S. generally gave equal support to both programmes. Newspapers from the rest of the world were more favourable to the UK; Radio Moscow

Radio Moscow (), also known as Radio Moscow World Service, was the official international broadcasting station of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics until 1993, when it was reorganized into Voice of Russia, which was subsequently reorga ...

went so far to publicly congratulate the UK while failing to mention the U.S. results at all.

As ZETA continued to generate positive results, plans were made to build a follow-on machine. The new design was announced in May; ZETA II would be a significantly larger US$14 million machine whose explicit goal would be to reach 100 million K, and generate net power. This announcement gathered praise even in the US; ''The New York Times'' ran a story about the new version. Machines similar to ZETA were being announced around the world; Osaka University

The , abbreviated as UOsaka or , is a List of national universities in Japan, national research university in Osaka, Japan. The university traces its roots back to Edo period, Edo-era institutions Tekijuku (1838) and Kaitokudō, Kaitokudo (1724), ...

announced their pinch machine was even more successful than ZETA, the Aldermaston team announced positive results from their Sceptre machine costing only US$28,000, and a new reactor was built in Uppsala University

Uppsala University (UU) () is a public university, public research university in Uppsala, Sweden. Founded in 1477, it is the List of universities in Sweden, oldest university in Sweden and the Nordic countries still in operation.

Initially fou ...

that was presented publicly later that year. The Efremov Institute in Leningrad

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

began construction of a smaller version of ZETA, although still larger than most, known as Alpha.

Further scepticism, retraction of claims

Spitzer had already concluded that known theory suggested that the ZETA was nowhere near the temperatures the team was claiming, and during the publicity surrounding the release of the work, he suggested that "Some unknown mechanism would appear to be involved". Other researchers in the U.S., notably Furth and Colgate, were far more critical, telling anyone who would listen that the results were bunk. In the Soviet Union,Lev Artsimovich

Lev Andreyevich Artsimovich ( Russian: Лев Андреевич Арцимович, February 25, 1909 – March 1, 1973), also transliterated Arzimowitsch, was a Soviet physicist known for his contributions to the Tokamak— a device that produ ...

rushed to have the ''Nature'' article translated, and after reading it, declared "Chush sobachi!" (bullshit).

Cockcroft had stated that they were receiving too few neutrons from the device to measure their spectrum or their direction. Failing to do so meant they could not eliminate the possibility that the neutrons were being released due to electrical effects in the plasma, the sorts of reactions that Kurchatov had pointed out earlier.

In fact, such measurements would have been easy to make. In the same converted hangar that housed ZETA was the Harwell Synchrocyclotron effort run by Basil Rose. This project had built a sensitive high-pressure diffusion cloud chamber

A cloud chamber, also known as a Wilson chamber, is a particle detector used for visualizing the passage of ionizing radiation.

A cloud chamber consists of a sealed environment containing a supersaturated vapor of water or alcohol. An energetic ...

as the cyclotron's main detector. Rose was convinced it would be able to directly measure the neutron energies and trajectories.

In a series of experiments in February and March 1958, he showed that the neutrons had a high directionality, at odds with a fusion origin which would be expected to be randomly directed. To further demonstrate this he had the machine run with the current in the discharge current running "backwards". Had the neutrons been from fusion, the net velocity should have been zero, that is, they should have been travelling in random directions. The measurements showed this was not the case, not only was there a clear directionality to their release, it reversed when the current was reversed. This suggested the neutrons were a result of the electric current itself, not fusion reactions inside the plasma. They also noted that the energy of the neutrons was extremely close to that of a D-D fusion reaction, which suggested that the source was D particles colliding with a solid in the reactor.

This was followed by similar experiments on Perhapsatron and Columbus, demonstrating the same problems. The issue was a new form of instability, the "microinstabilities" or MHD instabilities, that were caused by wave-like signals in the plasma. These had been predicted, but whereas the kink was on the scale of the entire plasma and could be easily seen in photographs, these microinstabilities were too small and rapidly moving to easily detect, and had simply not been noticed before. But like the kink, when these instabilities developed, areas of enormous electrical potential developed, rapidly accelerating protons in the area. These sometimes collided with neutrons in the plasma or the container walls, ejecting them through neutron spallation. This is the same physical process that had been creating neutrons in earlier designs, the problem Cockcroft had mentioned during the press releases, but their underlying cause was more difficult to see and in ZETA they were much more powerful. The promise of stabilised pinch disappeared.

Cockcroft was forced to publish a humiliating retraction on 16 May 1958, claiming "It is doing exactly the job we expected it would do and is functioning exactly the way we hoped it would." ''Le Monde

(; ) is a mass media in France, French daily afternoon list of newspapers in France, newspaper. It is the main publication of Le Monde Group and reported an average print circulation, circulation of 480,000 copies per issue in 2022, including ...

'' raised the issue to a front-page headline in June, noting "Contrary to what was announced six months ago at Harwell – British experts confirm that thermonuclear energy has not been 'domesticated. The event cast a chill over the entire field; it was not only the British who looked foolish, every other country involved in fusion research had been quick to jump on the bandwagon.

Harwell in turmoil, ZETA soldiers on

Beginning in 1955, Cockcroft had pressed for the establishment of a new site for the construction of multiple prototype power-producing fission reactors. This was strongly opposed by Christopher Hinton, and a furious debate broke out within the UKAEA over the issue. Cockcroft eventually won the debate, and in late 1958 the UKAEA formed AEE Winfrith inDorset

Dorset ( ; Archaism, archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by Somerset to the north-west, Wiltshire to the north and the north-east, Hampshire to the east, t ...

, where they eventually built several experimental reactor designs.

Cockcroft had also pressed for the ZETA II reactor to be housed at the new site. He argued that Winfrith would be better suited to build the large reactor, and the unclassified site would better suit the now-unclassified research. This led to what has been described as "as close to a rebellion that the individualistic scientists at Harwell could possibly mount". Thonemann made it clear he was not interested in moving to Dorset and suggested that several other high-ranking members would also quit rather than move. He then went on sabbatical to Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial ...

for a year. The entire affair was a major strain on Basil Schonland

Sir Basil Ferdinand Jamieson Schonland OMG CBE FRS (2 February 1896 – 24 November 1972) was noted for his research on lightning, his involvement in the development of radar during World War II and for being the first president of the South ...

, who took over the Research division when Cockcroft left in October 1959 to become the Master of the newly formed Churchill College, Cambridge