Wyatt Outlaw on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Wyatt Outlaw (1820February 26, 1870) was an American politician and the first African-American to serve as Town Commissioner and Constable of the town of

Outlaw, whose trade was woodworking and cabinet-making, was an African-American community leader in Alamance County. In 1866 he founded or cofounded the Loyal Republican League in Alamance. In 1868, Outlaw was among a number of trustees who were deeded land for the establishment of the first

Outlaw, whose trade was woodworking and cabinet-making, was an African-American community leader in Alamance County. In 1866 he founded or cofounded the Loyal Republican League in Alamance. In 1868, Outlaw was among a number of trustees who were deeded land for the establishment of the first Wyatt Outlaw memorial ODMP website

/ref> A local African-American man named Puryear claimed to know who was responsible for the lynching, but Puryear was soon found dead in a nearby pond. In 1873,

Graham, North Carolina

Graham is a city in Alamance County, North Carolina, United States. It is part of the Burlington, North Carolina Metropolitan Statistical Area. As of the 2020 census the population was 17,153. It is the county seat of Alamance County.

History ...

. He was lynched by the White Brotherhood, a branch of the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

on February 26, 1870.Nelson, Scott Reynolds, "Red Strings and Half-Brothers: Civil Wars in Alamance County, North Carolina" in John Inscoe and Robert Kenzer, ed., ''Enemies of the Country: Unionism in the South During the Civil War'' (University of Georgia Press, 2001), 37-53. His death, along with the assassination of white Republican State Senator John W. Stephens

John W. Stephens (October 13, 1834 – May 21, 1870) was a state senator from North Carolina. He was stabbed and garroted by the Ku Klux Klan on May 21, 1870.Caswell County Courthouse

Caswell County Courthouse is a historic county courthouse located in Yanceyville, Caswell County, North Carolina. It was built between 1858 and 1861, and is a rectangular two-story, stuccoed brick building, five bays wide and seven deep. It si ...

, provoked Governor William Woods Holden

William Woods Holden (November 24, 1818 – March 1, 1892) was an American politician who served as the List of Governors of North Carolina, 38th and 40th governor of North Carolina. He was appointed by President of the United States, President ...

to declare martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

in Alamance

Alamance is a village in Alamance County, North Carolina, Alamance County, North Carolina, United States. It is part of the Burlington, North Carolina Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 951 at the 2010 United States Census, 2010 cens ...

and Caswell Counties, resulting in the Kirk-Holden War of 1870.Troxler, Carole Watterson and William Murray Vincent (1999). ''Shuttle & Plow: A History of Alamance County, North Carolina''. Alamance County Historical Association.The Hillsboro Recorder, April 6, 1870.

Biography

Outlaw was apparently of mixed racial heritage. He was mentioned in a letter as being the son of a white Alamance County slave-owner Chesley F. Faucett. One source suggests he lived on the tobacco farm of Nancy Outlaw on Jordan Creek, northeast ofGraham, North Carolina

Graham is a city in Alamance County, North Carolina, United States. It is part of the Burlington, North Carolina Metropolitan Statistical Area. As of the 2020 census the population was 17,153. It is the county seat of Alamance County.

History ...

. Sources conflict on the question of whether Outlaw was born a slave or a free person of color.

Outlaw is probably the same person enlisted as "Wright Outlaw" in the 2nd Regiment U. S. Colored Cavalry in 1863 who fought in various engagements in Virginia and was later stationed on the Rio Grande

The Rio Grande ( and ), known in Mexico as the Río Bravo del Norte or simply the Río Bravo, is one of the principal rivers (along with the Colorado River) in the southwestern United States and in northern Mexico.

The length of the Rio G ...

in Texas until mustered out in February 1866.

Outlaw, whose trade was woodworking and cabinet-making, was an African-American community leader in Alamance County. In 1866 he founded or cofounded the Loyal Republican League in Alamance. In 1868, Outlaw was among a number of trustees who were deeded land for the establishment of the first

Outlaw, whose trade was woodworking and cabinet-making, was an African-American community leader in Alamance County. In 1866 he founded or cofounded the Loyal Republican League in Alamance. In 1868, Outlaw was among a number of trustees who were deeded land for the establishment of the first African Methodist Episcopal Church

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, usually called the AME Church or AME, is a Black church, predominantly African American Methodist Religious denomination, denomination. It adheres to Wesleyan-Arminian theology and has a connexionalism, c ...

in Alamance County. Outlaw's Loyal Republican League was later incorporated into the Union League

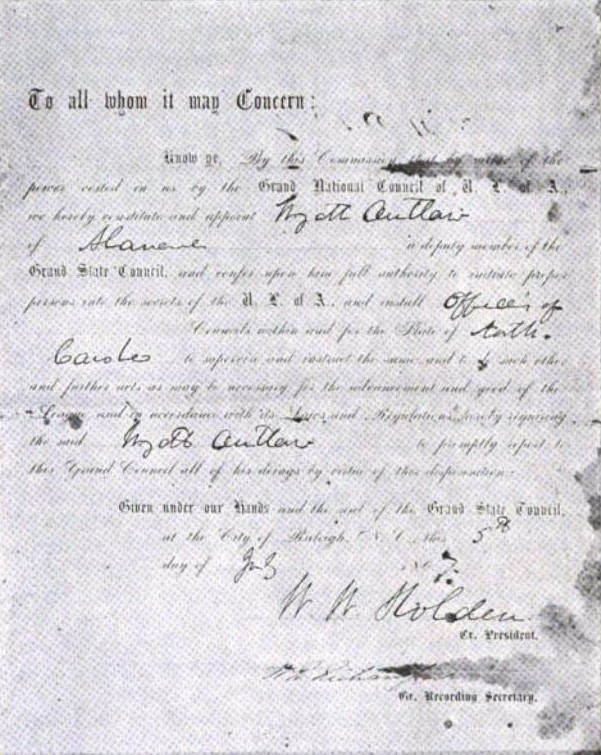

The Union Leagues were quasi-secretive men’s clubs established separately, starting in 1862, and continuing throughout the Civil War (1861–1865). The oldest Union League of America council member, an organization originally called "The Leag ...

, a fraternal order connected to the Republican Party.

Outlaw's prominent activities on behalf of African Americans in Alamance County made him a target of the White Brotherhood and the Constitutional Union Guard, both local branches of the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

. As a prominent Republican in Alamance County, Outlaw was appointed to the Graham Town Council by Governor Holden and soon became one of three constables of the town – all three of whom were African Americans.Whitaker, Walter (1949). ''Centennial History of Alamance County 1849-1949''. Burlington Chamber of Commerce. On one occasion in 1869, white residents of the area who were incensed by the prospect of being policed by an all African-American constabulary organized a nighttime ride in Klan garb through the streets of Graham in an effort to frighten the African-American constables. Outlaw and another constable opened fire on the night riders, but no injuries were sustained.

Outlaw's aggressive response to the night riders may have inflamed the anger of Klan sympathizers. The night of February 26, 1870, a party of unidentified men rode into Graham, dragged Outlaw from his home and hung him from an elm tree in the courthouse square in Graham, in what is now known as Sesquicentennial Park, located at .Grand jury testimony of James Fonville, recorded in The Southern Home, March 7, 1871. http://lynching.web.unc.edu/files/2015/05/The_Southern_Home_Tue__Mar_7__1871_.jpg Outlaw's body bore on the chest a message from the perpetrators: "Beware, ye guilty, both black and white."The Greensboro Patriot, March 3, 1870./ref> A local African-American man named Puryear claimed to know who was responsible for the lynching, but Puryear was soon found dead in a nearby pond. In 1873,

Guilford County

Guilford County is a county located in the U.S. state of North Carolina. As of the 2020 census, the population is 541,299, making it the third-most populous county in North Carolina. The county seat, and largest municipality, is Greensboro. Si ...

Superior Court Judge Albion Tourgee

Albion is an alternative name for Great Britain. The oldest attestation of the toponym comes from the Greek language. It is sometimes used poetically and generally to refer to the island, but is less common than 'Britain' today. The name for Scot ...

advocated for re-visiting the murder of Wyatt Outlaw. That year the Grand Jury of Alamance County brought felony indictments against 63 Klansmen, including 18 murder counts, in connection with the lynching of Wyatt Outlaw. Among those were James Bradshaw, Jesse Thompson, Michael Michael Thompson Teer, Geo. Mebane, Henry Robison, George Rogers, John S. Dixon, Walter Thornton, David Johnson, Curry Johnson, James Johnson, Thomas Tate, and Van Buren Holt. However, the Democratic-controlled state legislature repealed the laws under which most of these indictments had been brought, so the charges were dropped. No one was ever tried in connection with Outlaw's murder.

Notes

{{DEFAULTSORT:Outlaw, Wyatt 1820 births 1870 deaths 1870 murders in the United States African-American politicians during the Reconstruction Era Activists for African-American civil rights Victims of the Ku Klux Klan Murdered African-American people Racially motivated violence against African Americans People murdered in North Carolina Lynching deaths in North Carolina People from Graham, North Carolina North Carolina Republicans African Americans in the American Civil War Union Army soldiers People of North Carolina in the American Civil War Ku Klux Klan in North Carolina