Wisdom of the crowd on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The wisdom of the crowd is the collective opinion of a diverse independent group of individuals rather than that of a single expert. This process, while not new to the

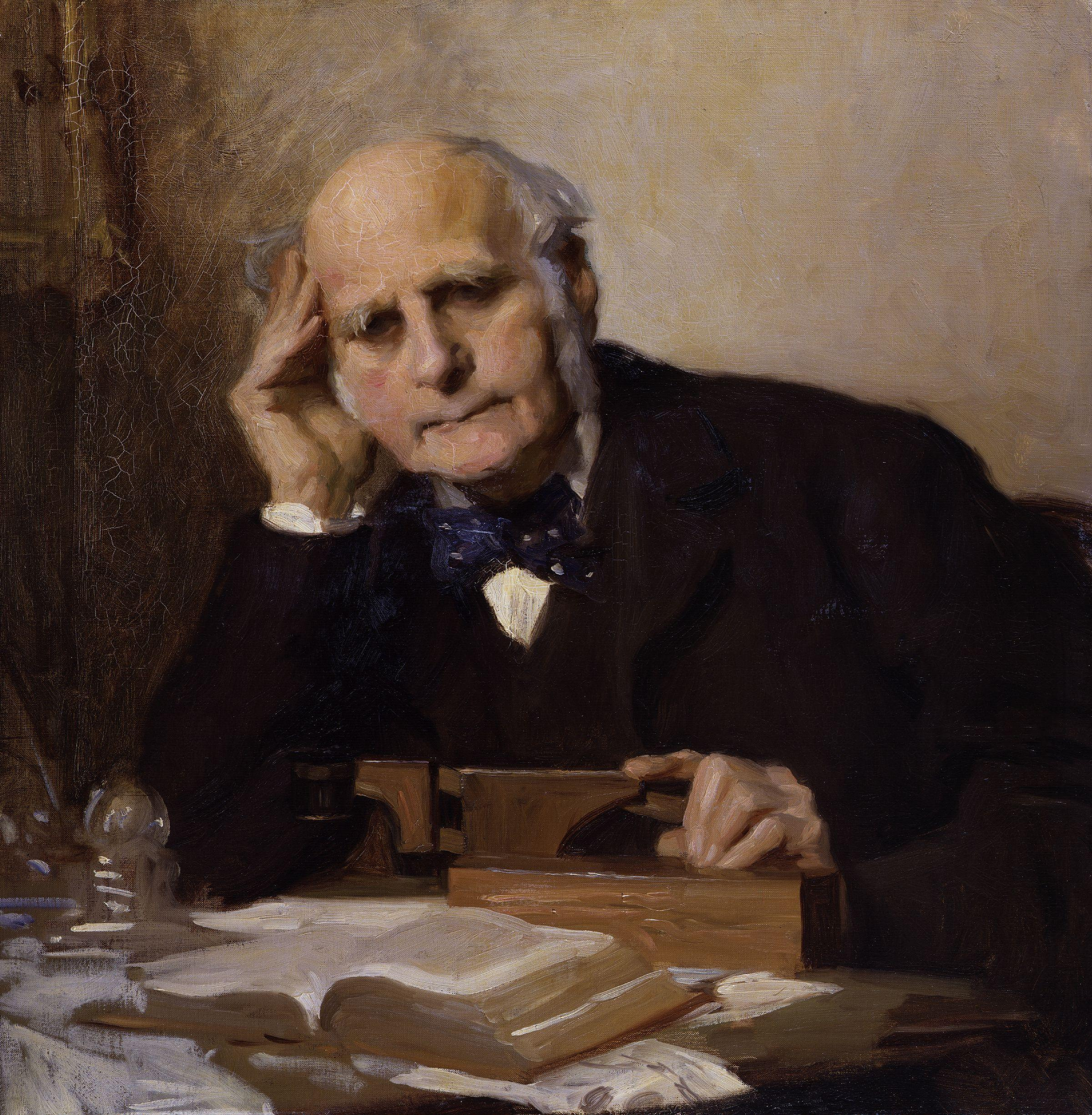

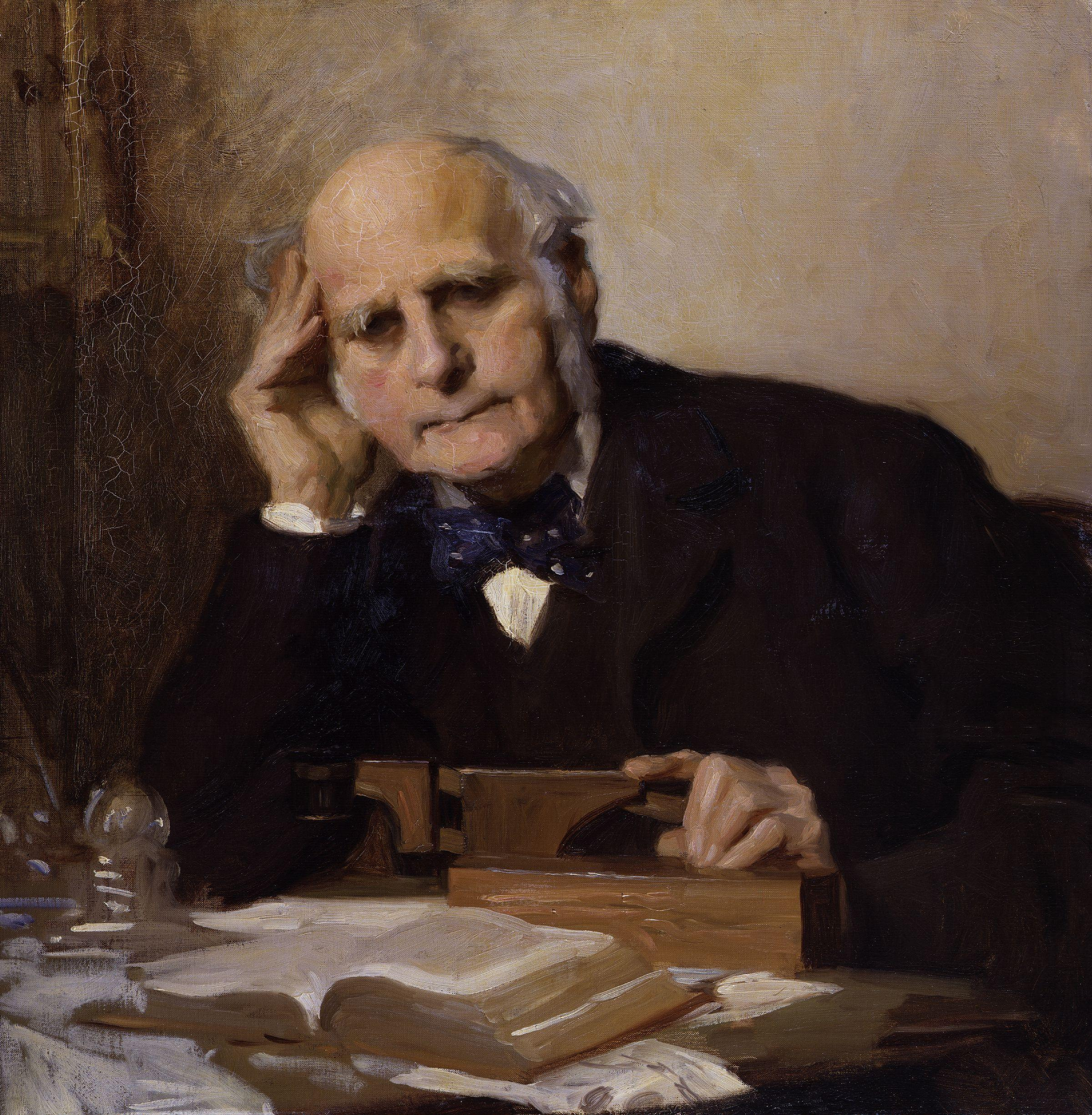

The classic wisdom-of-the-crowds finding involves point estimation of a continuous quantity. At a 1906 country fair in Plymouth, 800 people participated in a contest to estimate the weight of a slaughtered and dressed ox. Statistician Francis Galton observed that the median guess, 1207 pounds, was accurate within 1% of the true weight of 1198 pounds. This has contributed to the insight in cognitive science that a crowd's individual judgments can be modeled as a

The classic wisdom-of-the-crowds finding involves point estimation of a continuous quantity. At a 1906 country fair in Plymouth, 800 people participated in a contest to estimate the weight of a slaughtered and dressed ox. Statistician Francis Galton observed that the median guess, 1207 pounds, was accurate within 1% of the true weight of 1198 pounds. This has contributed to the insight in cognitive science that a crowd's individual judgments can be modeled as a

Information Age

The Information Age (also known as the Computer Age, Digital Age, Silicon Age, or New Media Age) is a historical period that began in the mid-20th century. It is characterized by a rapid shift from traditional industries, as established during ...

, has been pushed into the mainstream spotlight by social information sites such as Quora, Reddit

Reddit (; stylized in all lowercase as reddit) is an American social news aggregation, content rating, and discussion website. Registered users (commonly referred to as "Redditors") submit content to the site such as links, text posts, imag ...

, Stack Exchange, Wikipedia

Wikipedia is a multilingual free online encyclopedia written and maintained by a community of volunteers, known as Wikipedians, through open collaboration and using a wiki-based editing system. Wikipedia is the largest and most-read refer ...

, Yahoo! Answers

Yahoo! Answers was a community-driven question-and-answer (Q&A) website or knowledge market owned by Yahoo! where users would ask questions and answer those submitted by others, and upvote them to increase their visibility. Questions were org ...

, and other web resources which rely on collective human knowledge. An explanation for this phenomenon is that there is idiosyncratic noise associated with each individual judgment, and taking the average over a large number of responses will go some way toward canceling the effect of this noise.

Trial by jury can be understood as at least partly relying on wisdom of the crowd, compared to bench trial which relies on one or a few experts. In politics, sometimes sortition

In governance, sortition (also known as selection by lottery, selection by lot, allotment, demarchy, stochocracy, aleatoric democracy, democratic lottery, and lottocracy) is the selection of political officials as a random sample from a large ...

is held as an example of what wisdom of the crowd would look like. Decision-making would happen by a diverse group instead of by a fairly homogenous political group or party. Research within cognitive science has sought to model the relationship between wisdom of the crowd effects and individual cognition.

A large group's aggregated answers to questions involving quantity estimation, general world knowledge, and spatial reasoning has generally been found to be as good as, but often superior to, the answer given by any of the individuals within the group.

Jury theorems from social choice theory

Social choice theory or social choice is a theoretical framework for analysis of combining individual opinions, preferences, interests, or welfares to reach a ''collective decision'' or ''social welfare'' in some sense.Amartya Sen (2008). "Soci ...

provide formal arguments for wisdom of the crowd given a variety of more or less plausible assumptions. Both the assumptions and the conclusions remain controversial, even though the theorems themselves are not. The oldest and simplest is Condorcet's jury theorem (1785).

Examples

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

is credited as the first person to write about the "wisdom of the crowd" in his work ''Politics

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that studies ...

''. According to Aristotle, "it is possible that the many, though not individually good men, yet when they come together may be better, not individually but collectively, than those who are so, just as public dinners to which many contribute are better than those supplied at one man's cost".

The classic wisdom-of-the-crowds finding involves point estimation of a continuous quantity. At a 1906 country fair in Plymouth, 800 people participated in a contest to estimate the weight of a slaughtered and dressed ox. Statistician Francis Galton observed that the median guess, 1207 pounds, was accurate within 1% of the true weight of 1198 pounds. This has contributed to the insight in cognitive science that a crowd's individual judgments can be modeled as a

The classic wisdom-of-the-crowds finding involves point estimation of a continuous quantity. At a 1906 country fair in Plymouth, 800 people participated in a contest to estimate the weight of a slaughtered and dressed ox. Statistician Francis Galton observed that the median guess, 1207 pounds, was accurate within 1% of the true weight of 1198 pounds. This has contributed to the insight in cognitive science that a crowd's individual judgments can be modeled as a probability distribution

In probability theory and statistics, a probability distribution is the mathematical function that gives the probabilities of occurrence of different possible outcomes for an experiment. It is a mathematical description of a random phenomenon ...

of responses with the median centered near the true value of the quantity to be estimated.

In recent years, the "wisdom of the crowd" phenomenon has been leveraged in business strategy and advertising spaces. Firms such as Napkin Labs aggregate consumer feedback and brand impressions for clients. Meanwhile, companies such as Trada invoke crowds to design advertisements based on clients' requirements.

Non-human examples are prevalent. For example, the golden shiner is a fish that prefers shady areas. The single shiner has a very difficult time finding shady regions in a body of water whereas a large group is much more efficient at finding the shade.

Higher-dimensional problems and modeling

Although classic wisdom-of-the-crowds findings center on point estimates of single continuous quantities, the phenomenon also scales up to higher-dimensional problems that do not lend themselves to aggregation methods such as taking the mean. More complex models have been developed for these purposes. A few examples of higher-dimensional problems that exhibit wisdom-of-the-crowds effects include: * Combinatorial problems such asminimum spanning tree

A minimum spanning tree (MST) or minimum weight spanning tree is a subset of the edges of a connected, edge-weighted undirected graph that connects all the vertices together, without any cycles and with the minimum possible total edge weight. ...

s and the traveling salesman problem, in which participants must find the shortest route between an array of points. Models of these problems either break the problem into common pieces (the ''local decomposition method'' of aggregation) or find solutions that are most similar to the individual human solutions (the ''global similarity aggregation'' method).

* Ordering problems such as the order of the U.S. presidents or world cities by population. A useful approach in this situation is Thurstonian modeling, which each participant has access to the ground truth ordering but with varying degrees of stochastic

Stochastic (, ) refers to the property of being well described by a random probability distribution. Although stochasticity and randomness are distinct in that the former refers to a modeling approach and the latter refers to phenomena themselv ...

noise

Noise is unwanted sound considered unpleasant, loud or disruptive to hearing. From a physics standpoint, there is no distinction between noise and desired sound, as both are vibrations through a medium, such as air or water. The difference aris ...

, leading to variance in the final ordering given by different individuals.

* Multi-armed bandit problems, in which participants choose from a set of alternatives with fixed but unknown reward rates with the goal of maximizing return after a number of trials. To accommodate mixtures of decision processes and individual differences in probabilities of ''winning and staying'' with a given alternative versus ''losing and shifting'' to another alternative, hierarchical Bayesian models have been employed which include parameters for individual people drawn from Gaussian

Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777–1855) is the eponym of all of the topics listed below.

There are over 100 topics all named after this German mathematician and scientist, all in the fields of mathematics, physics, and astronomy. The English eponym ...

distributions

Surprisingly popular

In further exploring the ways to improve the results, a new technique called the " surprisingly popular" was developed by scientists at MIT's Sloan Neuroeconomics Lab in collaboration with Princeton University. For a given question, people are asked to give two responses: What they think the right answer is, and what they think popular opinion will be. The averaged difference between the two indicates the correct answer. It was found that the "surprisingly popular" algorithm reduces errors by 21.3 percent in comparison to simple majority votes, and by 24.2 percent in comparison to basic confidence-weighted votes where people express how confident they are of their answers and 22.2 percent compared to advanced confidence-weighted votes, where one only uses the answers with the highest average.Definition of crowd

In the context of wisdom of the crowd, the term "crowd" takes on a broad meaning. One definition characterizes a crowd as a group of people amassed by an open call for participation. While crowds are often leveraged in online applications, they can also be utilized in offline contexts. In some cases, members of a crowd may be offered monetary incentives for participation. Certain applications of "wisdom of the crowd", such as jury duty in the United States, mandate crowd participation.Analogues with individual cognition: the "crowd within"

The insight that crowd responses to an estimation task can be modeled as a sample from aprobability distribution

In probability theory and statistics, a probability distribution is the mathematical function that gives the probabilities of occurrence of different possible outcomes for an experiment. It is a mathematical description of a random phenomenon ...

invites comparisons with individual cognition. In particular, it is possible that individual cognition is probabilistic in the sense that individual estimates are drawn from an "internal probability distribution." If this is the case, then two or more estimates of the same quantity from the same person should average to a value closer to ground truth than either of the individual judgments, since the effect of statistical noise within each of these judgments is reduced. This of course rests on the assumption that the noise associated with each judgment is (at least somewhat) statistically independent. Thus, the crowd needs to be independent but also diversified, in order to allow a variety of answers. The answers on the ends of the spectrum will cancel each other, allowing the wisdom of the crowd phenomena to take its place. Another caveat is that individual probability judgments are often biased toward extreme values (e.g., 0 or 1). Thus any beneficial effect of multiple judgments from the same person is likely to be limited to samples from an unbiased distribution.

Vul and Pashler (2008) asked participants for point estimates of continuous quantities associated with general world knowledge, such as "What percentage of the world's airports are in the United States?" Without being alerted to the procedure in advance, half of the participants were immediately asked to make a second, different guess in response to the same question, and the other half were asked to do this three weeks later. The average of a participant's two guesses was more accurate than either individual guess. Furthermore, the averages of guesses made in the three-week delay condition were more accurate than guesses made in immediate succession. One explanation of this effect is that guesses in the immediate condition were less independent of each other (an anchoring effect) and were thus subject to (some of) the same kind of noise. In general, these results suggest that individual cognition may indeed be subject to an internal probability distribution characterized by stochastic noise, rather than consistently producing the best answer based on all the knowledge a person has. These results were mostly confirmed in a high-powered pre-registered replication. The only result that was not fully replicated was that a delay in the second guess generates a better estimate.

Hourihan and Benjamin (2010) tested the hypothesis that the estimate improvements observed by Vul and Pashler in the delayed responding condition were the result of increased independence of the estimates. To do this Hourihan and Benjamin capitalized on variations in memory span In psychology and neuroscience, memory span is the longest list of items that a person can repeat back in correct order immediately after presentation on 50% of all trials. Items may include words, numbers, or letters. The task is known as ''digit ...

among their participants. In support they found that averaging repeated estimates of those with lower memory spans showed greater estimate improvements than the averaging the repeated estimates of those with larger memory spans.

Rauhut and Lorenz (2011) expanded on this research by again asking participants to make estimates of continuous quantities related to real world knowledge – however, in this case participants were informed that they would make five consecutive estimates. This approach allowed the researchers to determine, firstly, the number of times one needs to ask oneself in order to match the accuracy of asking others and then, the rate at which estimates made by oneself improve estimates compared to asking others. The authors concluded that asking oneself an infinite number of times does not surpass the accuracy of asking just one other individual. Overall, they found little support for a so-called "mental distribution" from which individuals draw their estimates; in fact, they found that in some cases asking oneself multiple times actually reduces accuracy. Ultimately, they argue that the results of Vul and Pashler (2008) overestimate the wisdom of the "crowd within" – as their results show that asking oneself more than three times actually reduces accuracy to levels below that reported by Vul and Pashler (who only asked participants to make two estimates).

Müller-Trede (2011) attempted to investigate the types of questions in which utilizing the "crowd within" is most effective. He found that while accuracy gains were smaller than would be expected from averaging ones' estimates with another individual, repeated judgments lead to increases in accuracy for both year estimation questions (e.g., when was the thermometer invented?) and questions about estimated percentages (e.g., what percentage of internet users connect from China?). General numerical questions (e.g., what is the speed of sound, in kilometers per hour?), however, did not show improvement with repeated judgments, while averaging individual judgments with those of a random other did improve accuracy. This, Müller-Trede argues, is the result of the bounds implied by year and percentage questions.

Van Dolder and Van den Assem (2018) studied the "crowd within" using a large database from three estimation competitions organised by Holland Casino. For each of these competitions, they find that within-person aggregation indeed improves accuracy of estimates. Furthermore, they also confirm that this method works better if there is a time delay between subsequent judgments. However, even when there is considerable delay between estimates, the benefit pales against that of between-person aggregation: the average of a large number of judgements from the same person is barely better than the average of two judgements from different people.

Dialectical bootstrapping: improving the estimates of the "crowd within"

Herzog and Hertwig (2009) attempted to improve on the "wisdom of many in one mind" (i.e., the "crowd within") by asking participants to use dialectical bootstrapping. Dialectical bootstrapping involves the use ofdialectic

Dialectic ( grc-gre, διαλεκτική, ''dialektikḗ''; related to dialogue; german: Dialektik), also known as the dialectical method, is a discourse between two or more people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing ...

(reasoned discussion that takes place between two or more parties with opposing views, in an attempt to determine the best answer) and bootstrapping (advancing oneself without the assistance of external forces). They posited that people should be able to make greater improvements on their original estimates by basing the second estimate on antithetical information. Therefore, these second estimates, based on different assumptions and knowledge than that used to generate the first estimate would also have a different error (both systematic and random

In common usage, randomness is the apparent or actual lack of pattern or predictability in events. A random sequence of events, symbols or steps often has no order and does not follow an intelligible pattern or combination. Individual ran ...

) than the first estimate – increasing the accuracy of the average judgment. From an analytical perspective dialectical bootstrapping should increase accuracy so long as the dialectical estimate is not too far off and the errors of the first and dialectical estimates are different. To test this, Herzog and Hertwig asked participants to make a series of date estimations regarding historical events (e.g., when electricity was discovered), without knowledge that they would be asked to provide a second estimate. Next, half of the participants were simply asked to make a second estimate. The other half were asked to use a consider-the-opposite strategy to make dialectical estimates (using their initial estimates as a reference point). Specifically, participants were asked to imagine that their initial estimate was off, consider what information may have been wrong, what this alternative information would suggest, if that would have made their estimate an overestimate or an underestimate, and finally, based on this perspective what their new estimate would be. Results of this study revealed that while dialectical bootstrapping did not outperform the wisdom of the crowd (averaging each participants' first estimate with that of a random other participant), it did render better estimates than simply asking individuals to make two estimates.

Hirt and Markman (1995) found that participants need not be limited to a consider-the-opposite strategy in order to improve judgments. Researchers asked participants to consider-an-alternative – operationalized as any plausible alternative (rather than simply focusing on the "opposite" alternative) – finding that simply considering an alternative improved judgments.

Not all studies have shown support for the "crowd within" improving judgments. Ariely and colleagues asked participants to provide responses based on their answers to true-false items and their confidence in those answers. They found that while averaging judgment estimates between individuals significantly improved estimates, averaging repeated judgment estimates made by the same individuals did not significantly improve estimates.

Problems

Wisdom-of-the-crowds research routinely attributes the superiority of crowd averages over individual judgments to the elimination of individual noise, an explanation that assumesindependence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the stat ...

of the individual judgments from each other. Thus the crowd tends to make its best decisions if it is made up of diverse opinions and ideologies.

Averaging can eliminate random error

Observational error (or measurement error) is the difference between a measured value of a quantity and its true value.Dodge, Y. (2003) ''The Oxford Dictionary of Statistical Terms'', OUP. In statistics, an error is not necessarily a "mistake" ...

s that affect each person's answer in a different way, but not systematic error

Observational error (or measurement error) is the difference between a measured value of a quantity and its true value.Dodge, Y. (2003) ''The Oxford Dictionary of Statistical Terms'', OUP. In statistics, an error is not necessarily a " mistak ...

s that affect the opinions of the entire crowd in the same way. So for instance, a wisdom-of-the-crowd technique would not be expected to compensate for cognitive biases.

Scott E. Page introduced the diversity prediction theorem: "The squared error of the collective prediction equals the average squared error minus the predictive diversity". Therefore, when the diversity in a group is large, the error of the crowd is small.

Miller and Stevyers reduced the independence of individual responses in a wisdom-of-the-crowds experiment by allowing limited communication between participants. Participants were asked to answer ordering questions for general knowledge questions such as the order of U.S. presidents. For half of the questions, each participant started with the ordering submitted by another participant (and alerted to this fact), and for the other half, they started with a random ordering, and in both cases were asked to rearrange them (if necessary) to the correct order. Answers where participants started with another participant's ranking were on average more accurate than those from the random starting condition. Miller and Steyvers conclude that different item-level knowledge among participants is responsible for this phenomenon, and that participants integrated and augmented previous participants' knowledge with their own knowledge.Miller, B., and Steyvers, M. (in press). "The Wisdom of Crowds with Communication". In L. Carlson, C. Hölscher, & T.F. Shipley (Eds.), ''Proceedings of the 33rd Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society''. Austin, TX: Cognitive Science Society.

Crowds tend to work best when there is a correct answer to the question being posed, such as a question about geography or mathematics. When there is not a precise answer crowds can come to arbitrary conclusions.

The wisdom of the crowd effect is easily undermined. Social influence can cause the average of the crowd answers to be wildly inaccurate, while the geometric mean and the median are far more robust.

(This relies on the uncertainty and trust, ergo experience of an individuals estimate to be known. i.e. the average of 10 learned individuals on a topic will vary from the average of 10 individuals who know nothing of the topic on hand even in a situation where a known truth exists and it is incorrect to just mix the total population of opinions assuming all to be equal as that will incorrectly dilute the impact of signal from the learned individuals over the noise of the un-educated.)

Experiments run by the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology found that when a group of people were asked to answer a question together they would attempt to come to a consensus which would frequently cause the accuracy of the answer to decrease. E.g. what is the length of a border between two countries? One suggestion to counter this effect is to ensure that the group contains a population with diverse backgrounds.

Research from the Good Judgment Project showed that teams organized in prediction polls can avoid premature consensus and produce aggregate probability estimates that are more accurate than those produced in prediction markets.

See also

* Argumentum ad populum * Bandwagon effect * Collaborative software * Collective intelligence * Collective wisdom *Conventional wisdom

The conventional wisdom or received opinion is the body of ideas or explanations generally accepted by the public and/or by experts in a field. In religion, this is known as orthodoxy.

Etymology

The term is often credited to the economist John ...

* Crowdfunding

Crowdfunding is the practice of funding a project or venture by raising money from a large number of people, typically via the internet. Crowdfunding is a form of crowdsourcing and alternative finance. In 2015, over was raised worldwide by cro ...

* Crowdsourcing

* Delphi method

* Dispersed knowledge

* Dollar voting

Dollar voting is an analogy that refers to the theoretical impact of consumer choice on producers' actions by means of the flow of consumer payments to producers for their goods and services.

Overview

In some principles-of-economics textbooks of ...

* Dunning–Kruger effect

* Emergence

* Ensemble forecasting

Ensemble forecasting is a method used in or within numerical weather prediction. Instead of making a single forecast of the most likely weather, a set (or ensemble) of forecasts is produced. This set of forecasts aims to give an indication of the ...

* The Good Judgment Project

The Good Judgment Project (GJP) is an organization dedicated to "harnessing the wisdom of the crowd to forecast world events". It was co-created by Philip E. Tetlock (author of ''Superforecasting'' and ''Expert Political Judgment''), decision sci ...

(forecasting project)

* Groupthink

* Human reliability

* Intrade

* Law of large numbers

* Linus's law

In software development, Linus's law is the assertion that "given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow".

The law was formulated by Eric S. Raymond in his essay and book ''The Cathedral and the Bazaar'' (1999), and was named in honor of Linus To ...

* Networked expertise

* Open source

* Pilot error

* Tyranny of the majority

* '' Vox populi''

* '' The Wisdom of Crowds''

References

External links

{{YouTube, s7tngG2kAik, The wisdom of the crowd (with Professor Marcus du Sautoy) Crowdsourcing Social information processing Wisdom Crowd psychology Crowds ja:集合知