William Schaw on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Schaw (c. 1550–1602) was Master of Works to

On 21 December 1583,

On 21 December 1583,

In 1589 Schaw was amongst the courtiers who accompanied James VI to Denmark to fetch his new queen Anna of Denmark. He returned on 15 March 1590, ahead of the rest of the party to prepare for their subsequent return. Schaw brought with him a Danish carpenter or woodturner called Frederick who would join the queen's household. Schaw busied himself repairing

In 1589 Schaw was amongst the courtiers who accompanied James VI to Denmark to fetch his new queen Anna of Denmark. He returned on 15 March 1590, ahead of the rest of the party to prepare for their subsequent return. Schaw brought with him a Danish carpenter or woodturner called Frederick who would join the queen's household. Schaw busied himself repairing

Schaw died in 1602. He was succeeded as King's Master of Works by

Schaw died in 1602. He was succeeded as King's Master of Works by

On 28 December 1598 Schaw, in his capacity of Master of Works and General Warden of the master stonemasons, issued "The Statutis and ordinananceis to be obseruit by all the maister maoissounis within this realme." The preamble states that the statutes were issued with the consent of a craft convention, simply specified as all the master masons gathered that day. Schaw's first statutes root themselves in the

On 28 December 1598 Schaw, in his capacity of Master of Works and General Warden of the master stonemasons, issued "The Statutis and ordinananceis to be obseruit by all the maister maoissounis within this realme." The preamble states that the statutes were issued with the consent of a craft convention, simply specified as all the master masons gathered that day. Schaw's first statutes root themselves in the

Grand Lodge of Antient, Free and Accepted Masons of Scotland

/ref>

Summary of the Second Schaw Statutes, in ''HMC Report: Earl of Eglinton'' (London, 1885), pp. 29–30

'THE SCHAW MONUMENT', Church Monuments Society

Transcript of William Schaw's Dalkeith letter

A gold salamander jewel from the wreck of the Girona, Ulster Museum, Armada gallery

James VI of Scotland

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until ...

for building castles and palaces, and is claimed to have been an important figure in the development of Freemasonry in Scotland

Freemasonry in Scotland in lodges chartered by the Grand Lodge of Scotland comprises the ''Scottish Masonic Constitution'' as regular Masonic jurisdiction for the majority of freemasons in Scotland. There are also lodges operating under the Scott ...

.

Biography

William Schaw was the second son of John Schaw of Broich, and grandson of Sir James Schaw ofSauchie

Sauchie is a town in the Central Lowlands of Scotland. It lies north of the River Forth and south of the Ochil Hills, within the council area of Clackmannanshire. Sauchie has a population of around 6000 and is located northeast of Alloa and ...

. Broich is now called Arngomery, a place at Kippen

Kippen is a village in west Stirlingshire, Scotland. It lies between the Gargunnock Hills and the Fintry Hills and overlooks the Carse of Forth to the north. The village is west of Stirling and north of Glasgow. It is south-east of Loch Lo ...

in Stirlingshire. The Schaw family had links to the Royal Court, principally through being keepers of the King's wine cellar. The Broich family was involved in a scandal in 1560, when John Schaw was accused of murdering the servant of another laird. William's father was denounced as a rebel and his property forfeited when he and his family failed to appear at court, but the family were soon re-instated. At this time William may have been a page at the court of Mary of Guise

Mary of Guise (french: Marie de Guise; 22 November 1515 – 11 June 1560), also called Mary of Lorraine, was a French noblewoman of the House of Guise, a cadet branch of the House of Lorraine and one of the most powerful families in France. Sh ...

, as a page of that name received an outfit of black mourning cloth when Mary of Guise

Mary of Guise (french: Marie de Guise; 22 November 1515 – 11 June 1560), also called Mary of Lorraine, was a French noblewoman of the House of Guise, a cadet branch of the House of Lorraine and one of the most powerful families in France. Sh ...

died. William the page would have been in Edinburgh Castle

Edinburgh Castle is a historic castle in Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland. It stands on Castle Rock (Edinburgh), Castle Rock, which has been occupied by humans since at least the Iron Age, although the nature of the early settlement is unclear. ...

with the Regent's court during the siege of Leith, while the Master of Work, William MacDowall, was strengthening the castle's defences.

The name "William Schaw" appears again in a 1580 note about courtiers made by an informant or spy at the royal court, the letter was sent to England. Schaw was described as the "clock-keeper" amongst followers of the King's favourite Esmé Stewart, 1st Duke of Lennox

Esmé Stewart, 1st Duke of Lennox, 1st Earl of Lennox, 6th Seigneur d'Aubigny, (26 May 1583) of the Château d'Aubigny at Aubigny-sur-Nère in the ancient province of Berry, France, was a Roman Catholic French nobleman of Scottish ancestry ...

, while another man John Hume was the keeper of " ratches", an old word meaning a kind of tenacious hunting scent hound

Franz Rudolf Frisching in the uniform of an officer of the Bernese Huntsmen Corps with his Berner Laufhund, painted by Jean Preudhomme in 1785

Scent hounds (or scenthounds) are a Dog type, type of hound that primarily hunts by scent rather than ...

.

Schaw signed the negative confession

The Negative Confession (Latin: ), sometimes known as the King's Confession, is a confession of faith issued by King James VI of Scotland on 2 March 1580 (Old Style).

Background

In 1580 Scottish Protestants feared the influence of Counter-Reform ...

whereby courtiers pledged allegiance to the Scottish Reformation

The Scottish Reformation was the process by which Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland broke with the Pope, Papacy and developed a predominantly Calvinist national Church of Scotland, Kirk (church), which was strongly Presbyterianism, Presbyterian in ...

. On 11 April 1581, he was given a valuable gift of rights over the lands in Kippen belonging to the Grahams of Fintry. In May 1583, he was in Paris at the death of the exiled Esmé Stewart and it was said that he took Esmé's heart back to Scotland.

Great Master of Work

On 21 December 1583,

On 21 December 1583, James VI

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

appointed Schaw principal Maister o' Wark (Master of Works) to the Crown of Scotland for life, with responsibility for all royal castles and palaces. Schaw had already been paid the first instalment of his salary £166-13s-4d as 'grete Mr of wark in place of Sir Robert Drummond' in November. The replacement of the incumbent Robert Drummond of Carnock with Schaw, known as a Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

, may have been a reaction to the Ruthven Raid that had removed Lennox from power.Stevenson, p. 28 By the terms of his appointment, Schaw for the rest of his life was to be;

'Grit maister of wark of all and sindrie his hienes palaceis, biggingis and reparationis, – and greit oversear, directour and commander of quhatsumevir police devysit or to be devysit for our soverane lordis behuif and plessur.' or, in modern spelling; 'Great master of work of all and sundry his highness' palaces, building works and repairs, – and great overseer, director and commander of whatsoever policy devised or to be devised for our sovereign lord's behalf and pleasure.'In November 1583 Schaw travelled on a diplomatic trip to France with

Lord Seton

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or a ...

and his son Alexander Seton, a fellow Catholic with an interest in architecture. The Seton family remained supporters of Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of S ...

who was exiled in England. Schaw returned in the winter of 1584, and became involved in building work for the Seton family. In 1585 he was one of three courtiers who entertained three Danish ambassadors visiting the Scottish court at Dunfermline

Dunfermline (; sco, Dunfaurlin, gd, Dùn Phàrlain) is a city, parish and former Royal Burgh, in Fife, Scotland, on high ground from the northern shore of the Firth of Forth. The city currently has an estimated population of 58,508. Acco ...

and St Andrews

St Andrews ( la, S. Andrea(s); sco, Saunt Aundraes; gd, Cill Rìmhinn) is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fourt ...

. In 1588 Schaw was amongst a group of Catholics ordered to appear before the Edinburgh Presbytery, and English agents reported him as being a suspected Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

and holding anti-English views during the 1590s. He met an English Catholic, George More

Sir George More (28 November 1553 – 16 October 1632) was an English courtier and politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1584 and 1625.

Early life

More was the son of Sir William More of Loseley Park, Surrey ...

at Dalkeith Palace in September 1598.

In September 1591 Richard Cockburn of Clerkington

Sir Richard Cockburn of Clerkington, Lord Clerkintoun (1565–1627) was a senior government official in Scotland serving as Lord Privy Seal of Scotland during the reign of James VI.Anderson, William, ''The Scottish Nation; or the Surnames, F ...

was admitted as a Lord of Session

The senators of the College of Justice are judges of the College of Justice, a set of legal institutions involved in the administration of justice in Scotland. There are three types of senator: Lords of Session (judges of the Court of Session); ...

. According to the English ambassador Robert Bowes, Cockburn had been "Master of Ceremonies" and this office was transferred to William Schaw. These appointments followed the death of Lewis Bellenden. An account of the baptism and banquet for Prince Charles

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person to a ...

on 23 December 1600 mentions that Schaw was absent, and the role of Master of Ceremonies was taken by two other men.

In May 1596 an English paper listing reasons to suspect James VI of being himself a Roman Catholic, included the appointment of known Catholics to household offices, noting Schaw as 'Praefectum Architecturae,' his friend Alexander Seton as President of Council, and Lord Hume as the King's body guard. By this time he had acquired the barony of Sauchie.

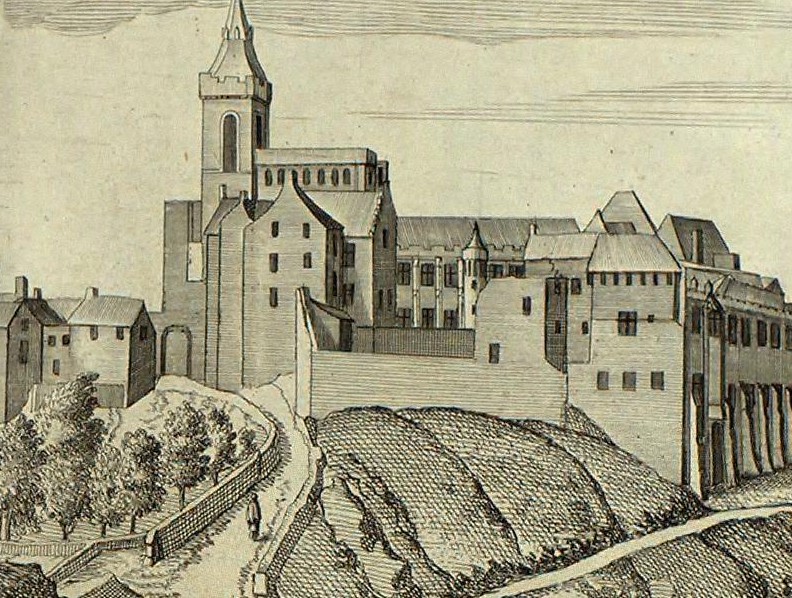

Some payments for Schaw's building work, at Falkland Palace

Falkland Palace, in Falkland, Fife, Scotland, is a royal palace of the Scottish Kings. It was one of the favourite places of Mary, Queen of Scots, providing an escape from political and religious turmoil. Today it is under the stewardship of ...

and Stirling Castle

Stirling Castle, located in Stirling, is one of the largest and most important castles in Scotland, both historically and architecturally. The castle sits atop Castle Hill, an intrusive crag, which forms part of the Stirling Sill geological ...

are documented by exchequer vouchers in the National Records of Scotland

, type = Non-ministerial government department

, logo = National Records of Scotland logo.svg

, logo_width =

, picture =

, picture_width =

, picture_caption =

, formed =

, preceding1 = National Archives of Scotland

, preceding2 = General Regi ...

. A record of the building work at the Palace of Holyroodhouse he supervised in 1599 survives. The works involved masons, slaters, plumbers, and joiners making repairs to the court and the king's kitchens, the steeple and clock, and the King's billiard table, and other alterations to the palace. Schaw signed off the account weekly with his name, or as "Maistir of Wark". On 8 July 1601, James VI sent William to consult with Master John Gordon on the construction of a monument to the King's rescue from the Gowrie House conspiracy the previous year. James VI wrote to Gordon that William would "conferre with yow thairanent, that ye maye agree upon the forme, devyse, and superscriptionis."

Servant of Anna of Denmark

In 1589 Schaw was amongst the courtiers who accompanied James VI to Denmark to fetch his new queen Anna of Denmark. He returned on 15 March 1590, ahead of the rest of the party to prepare for their subsequent return. Schaw brought with him a Danish carpenter or woodturner called Frederick who would join the queen's household. Schaw busied himself repairing

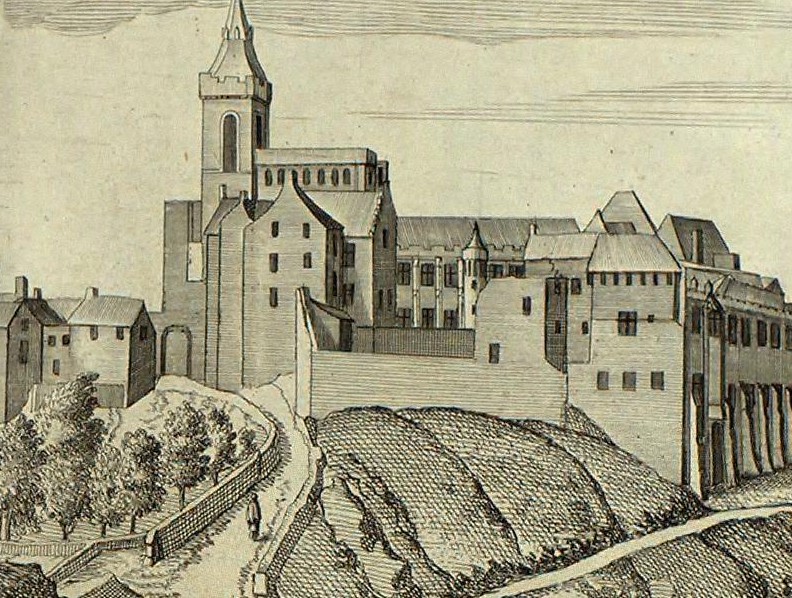

In 1589 Schaw was amongst the courtiers who accompanied James VI to Denmark to fetch his new queen Anna of Denmark. He returned on 15 March 1590, ahead of the rest of the party to prepare for their subsequent return. Schaw brought with him a Danish carpenter or woodturner called Frederick who would join the queen's household. Schaw busied himself repairing Holyrood Palace

The Palace of Holyroodhouse ( or ), commonly referred to as Holyrood Palace or Holyroodhouse, is the official residence of the British monarch in Scotland. Located at the bottom of the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, at the opposite end to Edinburgh ...

and Dunfermline Palace

Dunfermline Palace is a ruined former Scottish royal palace and important tourist attraction in Dunfermline, Fife, Scotland. It is currently, along with other buildings of the adjacent Dunfermline Abbey, under the care of Historic Environment ...

which had been assigned to the queen. He was given £1,000 Scots from tax money raised in Edinburgh for the royal marriage to spend on the repairs at Holyroodhouse. Queen Elizabeth

Queen Elizabeth, Queen Elisabeth or Elizabeth the Queen may refer to:

Queens regnant

* Elizabeth I (1533–1603; ), Queen of England and Ireland

* Elizabeth II (1926–2022; ), Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms

* Queen ...

gave a further 625 gold crowns to spend on Holyrood. Schaw was also responsible for the elaborate ceremony greeting her arrival at Leith

Leith (; gd, Lìte) is a port area in the north of the city of Edinburgh, Scotland, founded at the mouth of the Water of Leith. In 2021, it was ranked by ''Time Out'' as one of the top five neighbourhoods to live in the world.

The earliest ...

and the decoration of St Giles' Kirk with tapestry

Tapestry is a form of textile art, traditionally woven by hand on a loom. Tapestry is weft-faced weaving, in which all the warp threads are hidden in the completed work, unlike most woven textiles, where both the warp and the weft threads ma ...

for her coronation. He subsequently became Master of Ceremonies to the court, as his epitaph carved on his tomb states.

In June 1590 Schaw and his kinsman John Gibb, signed a bond in support of their relation James Gibb of Bo'ness

Borrowstounness (commonly known as Bo'ness ( )) is a town and former burgh and seaport on the south bank of the Firth of Forth in the Central Lowlands of Scotland. Historically part of the county of West Lothian, it is a place within the Fal ...

who had fought illegally in Edinburgh near Holyrood Palace with James Boyd of Kippis in a family feud. His death sentence was converted to banishment.

Schaw was involved in discussions with the Danish ambassadors Steen Bille

Steen Bille (1565–1629) was a Danish councillor and diplomat.

He was the son of Jens Bille and Karen Rønnow, and is sometimes called "Steen Jensen Bille". His father compiled a manuscript of ballads, Jens Billes visebog.

As a young man Bill ...

and Niels Krag

Niels Krag (1550-1602), was a Danish academic and diplomat.

Krag was a Doctor of Divinity, Professor at the University of Copenhagen, and historiographer Royal.

Mission to Scotland

In August 1589 the Danish council decided that Peder Munk, Breid ...

who came to Edinburgh in May 1593 to secure Anne of Denmark's property rights. On 6 July he was appointed as Chamberlain to the Lordship of Dunfermline, which was an office of the household of Queen Anna, where he worked closely with Alexander Seton and William Fowler. This involved receipting accounts for jewels the Queen bought from the goldsmith George Heriot

George Heriot (15 June 1563 – 12 February 1624) was a Scottish goldsmith and philanthropist. He is chiefly remembered today as the founder of George Heriot's School, a large independent school in Edinburgh; his name has also been given to H ...

, collecting rents 'feumaills' from her lands, and sometimes auditing the queen's household accounts kept by Harry Lindsay of Kinfauns for Sir George Home of Wedderburn.

Alterations at Dunfermline Abbey

Dunfermline Abbey is a Church of Scotland Parish Church in Dunfermline, Fife, Scotland. The church occupies the site of the ancient chancel and transepts of a large medieval Benedictine abbey, which was sacked in 1560 during the Scottish Reforma ...

were attributed to William Schaw's direction. He was said to have built a steeple, and a porch at the north door, added some of the external buttresses and fitted the interior for Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

worship as a burgh and Parish church between 1594 and 1599. Schaw spent other sums of money on the palaces allocated from the subsidy Elizabeth gave to James VI.

James VI and Anna built a new Chapel Royal

The Chapel Royal is an establishment in the Royal Household serving the spiritual needs of the sovereign and the British Royal Family. Historically it was a body of priests and singers that travelled with the monarch. The term is now also appl ...

at Stirling Castle

Stirling Castle, located in Stirling, is one of the largest and most important castles in Scotland, both historically and architecturally. The castle sits atop Castle Hill, an intrusive crag, which forms part of the Stirling Sill geological ...

in 1594, which has no documented association with Schaw, but was probably built under his direction. The Italianate building was used for the christening of James' and Anna's son Prince Henry Prince Henry (or Prince Harry) may refer to:

People

*Henry the Young King (1155–1183), son of Henry II of England, who was crowned king but predeceased his father

*Prince Henry the Navigator of Portugal (1394–1460)

*Henry, Duke of Cornwall (Ja ...

. The Queen gave him a hat badge in the form of a golden salamander

Salamanders are a group of amphibians typically characterized by their lizard-like appearance, with slender bodies, blunt snouts, short limbs projecting at right angles to the body, and the presence of a tail in both larvae and adults. All t ...

at New Year 1594–5. The badge was supplied by the jeweller Thomas Foulis

Thomas Foulis ( fl. 1580–1628) was a Scottish goldsmith, mine entrepreneur, and royal financier.

Thomas Foulis was an Edinburgh goldsmith and financier, and was involved in the mint and coinage, gold and lead mining, and from May 1591 the receip ...

.

In March 1598 he was tasked with giving the Queen's brother, Ulrik, Duke of Holstein a tour of Scotland with Esmé's son, Ludovic, Duke of Lennox, taking him to Fife

Fife (, ; gd, Fìobha, ; sco, Fife) is a council area, historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area of Scotland. It is situated between the Firth of Tay and the Firth of Forth, with inland boundaries with Perth and Kinross ...

and Ravenscraig Castle

Ravenscraig Castle is a ruined castle located in Kirkcaldy which dates from around 1460. The castle is an early example of artillery defence in Scotland.

History

The construction of Ravenscraig Castle by the mason Henry Merlion and the master ca ...

, Dundee, Stirling Castle, and on a trip to the Bass Rock

The Bass Rock, or simply the Bass (), ( gd, Creag nam Bathais or gd, Am Bas) is an island in the outer part of the Firth of Forth in the east of Scotland. Approximately offshore, and north-east of North Berwick, it is a steep-sided volca ...

. He provided furnishings for the pregnant queen at Dalkeith Palace, and in September met an English Catholic exile George More

Sir George More (28 November 1553 – 16 October 1632) was an English courtier and politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1584 and 1625.

Early life

More was the son of Sir William More of Loseley Park, Surrey ...

who came to Dalkeith.

Family and feud

His niece married Robert Mowbray, a grandson of thetreasurer

A treasurer is the person responsible for running the treasury of an organization. The significant core functions of a corporate treasurer include cash and liquidity management, risk management, and corporate finance.

Government

The treasury ...

Robert Barton

Robert Childers Barton (14 March 1881 – 10 August 1975) was an Anglo-Irish politician, Irish nationalist and farmer who participated in the negotiations leading up to the signature of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. His father was Charles William Bar ...

, and following his death she married James Colville of East Wemyss in 1601, which caused a family feud between Francis Mowbray

Francis Mowbray or Moubray (died 1603) was a Scottish intriguer.

Career

Francis Mowbray was a son of John Mowbray, Laird of Barnbougle Castle and Elspeth or Elizabeth Kirkcaldy, daughter of James Kirkcaldy.

His sisters, or half-sisters, Barba ...

, Robert's brother, and Schaw and Colville. Mowbray, an erstwhile English agent, wounded Schaw with a rapier

A rapier () or is a type of sword with a slender and sharply-pointed two-edged blade that was popular in Western Europe, both for civilian use (dueling and self-defense) and as a military side arm, throughout the 16th and 17th centuries.

Impo ...

in a quarrel, was subsequently arrested for plotting against the king, and died following an escape attempt from Edinburgh Castle

Edinburgh Castle is a historic castle in Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland. It stands on Castle Rock (Edinburgh), Castle Rock, which has been occupied by humans since at least the Iron Age, although the nature of the early settlement is unclear. ...

. Another niece, Elizabeth Schaw

Elizabeth Schaw (died 1640) was a Scottish courtier.

Elizabeth was the daughter of Sir John Schaw of Broich and Arngomery, a niece of William Schaw, and a lady-in-waiting to Anne of Denmark. Another Elizabeth Schaw, a cousin, the wife of Henry Li ...

of Broich, married John Murray of Lochmaben, an important courtier in the bedchamber, who became Earl of Annandale

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form ''jarl'', and meant "chieftain", particul ...

.

Schaw died in 1602. He was succeeded as King's Master of Works by

Schaw died in 1602. He was succeeded as King's Master of Works by David Cunninghame of Robertland

Sir David Cunningham of Robertland, in Ayrshire, was Master of Works to the Crown of Scotland from 1602 to 1607, and Surveyor of the King's Works in England from 1604 to 1606

Career Exiled for murder

Involved in the murder of the Earl of Eglint ...

.McKean, Charles (2001). ''The Scottish Chateau''. Sutton Publishing. . P. 158. His tomb in Dunfermline Abbey was constructed at the expense of his friend Alexander Seton and Queen Anne, and survives with a lengthy Latin inscription recording Schaw's intellectual skills and achievements. The tomb inscription remains the most valuable source of biographic information, and was composed by Alexander Seton, translated it reads:

This humble structure of stones covers a man of excellent skill, notable probity, singular integrity of life, adorned with the greatest of virtues – William Schaw, Master of the King's Works, President of the Sacred Ceremonies, and the Queen's Chamberlain. He died 18th April, 1602. Among the living he dwelt fifty-two years; he had travelled in France and many other Kingdoms, for the improvement of his mind; he wanted no liberal training; was most skilful in architecture; was early recommended to great persons for the singular gifts of his mind; and was not only unwearied and indefatigable in labours and business, but constantly active and vigorous, and was most dear to every good man who knew him. He was born to do good offices, and thereby to gain the hearts of men; now he lives eternally with God. Queen Anne ordered this monument to be erected to the memory of this most excellent and most upright man, lest his virtues, worthy of eternal commendation, should pass away with the death of his body."Elizabeth Shaw and James Schaw were William's executors. In 1612 the Privy Council of Scotland searched the accounts and found he was still owed his annual fee for several years. The council wrote to the king that he had been, "in his lyftime, and during the tyme of his service, he wes a most painefull, trustye, and welle affectit servand to your majestie."

Masonic Statutes

First Schaw Statutes

On 28 December 1598 Schaw, in his capacity of Master of Works and General Warden of the master stonemasons, issued "The Statutis and ordinananceis to be obseruit by all the maister maoissounis within this realme." The preamble states that the statutes were issued with the consent of a craft convention, simply specified as all the master masons gathered that day. Schaw's first statutes root themselves in the

On 28 December 1598 Schaw, in his capacity of Master of Works and General Warden of the master stonemasons, issued "The Statutis and ordinananceis to be obseruit by all the maister maoissounis within this realme." The preamble states that the statutes were issued with the consent of a craft convention, simply specified as all the master masons gathered that day. Schaw's first statutes root themselves in the Old Charges

There are a number of masonic manuscripts that are important in the study of the emergence of Freemasonry. Most numerous are the ''Old Charges'' or ''Constitutions''. These documents outlined a "history" of masonry, tracing its origins to a biblic ...

, with additional material to describe a hierarchy of wardens, deacons and masters. This structure would ensure that masons did not take on work which they were not competent to complete, and ensured a lodge warden would be elected by the master masons, through whom the general warden could keep in touch with each particular lodge. Master masons were only permitted to take on three apprentices during their lifetime (without special dispensation), and they would be bound to their masters for seven years. A further seven years would have to elapse before they could be taken into the craft, and a book-keeping arrangement was set up to keep track of this. Six master masons and two entered apprentices had to be present for a master or fellow of the craft to be admitted. Various other rules were laid out for the running of the lodge, supervision of work, and fines for non-attendance at lodge meetings.

The first point of the new statutes was that master masons in Scotland should;"observe and keep all the good ordinances set down of before, concerning the privileges of their craft, to their predecessours of good memory, and specially, they be true one to another, and live charitably together, as becomes sworn brothers and companions of craft."The statutes were agreed by all the master masons present, and arrangements were made to send a copy to every lodge in Scotland. The statute indicates a significant advance in the organisation of the craft, with

shire

Shire is a traditional term for an administrative division of land in Great Britain and some other English-speaking countries such as Australia and New Zealand. It is generally synonymous with county. It was first used in Wessex from the begin ...

s constituting an intermediate level of organisation. These "territorial" lodges ran parallel to another set of civic organisations, incorporations, often linking masons with other workers in the building trades, such as wright

Wright is an occupational surname originating in England. The term 'Wright' comes from the circa 700 AD Old English word 'wryhta' or 'wyrhta', meaning worker or shaper of wood. Later it became any occupational worker (for example, a shipwright i ...

s. While in some places (Stirling

Stirling (; sco, Stirlin; gd, Sruighlea ) is a city in central Scotland, northeast of Glasgow and north-west of Edinburgh. The market town, surrounded by rich farmland, grew up connecting the royal citadel, the medieval old town with its me ...

and Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

), the lodges and incorporations became indistinguishable, in other places the incorporation linked the trade to the burgh

A burgh is an autonomous municipal corporation in Scotland and Northern England, usually a city, town, or toun in Scots. This type of administrative division existed from the 12th century, when King David I created the first royal burghs. Bur ...

, and became a mechanism whereby the merchants exercised some control over the wages of the building trades. In places like Edinburgh, where the proliferation of wooden buildings meant a predominance of wrights, the territorial lodge offered a form of craft self-governance distinct from the incorporation. Also, the masons and wrights used differing ceremonial motifs, at the respective events. The role of deacon provided a link between these incorporations and the lodges.

Copies of the statute (along with the Second Shaw Statute) were written into the minutes of the Lodges of Edinburgh and Aitchison's Haven, near Prestonpans

Prestonpans ( gd, Baile an t-Sagairt, Scots language, Scots: ''The Pans'') is a small mining town, situated approximately eight miles east of Edinburgh, Scotland, in the Council area of East Lothian. The population as of is. It is near the si ...

.

Second Schaw Statutes

The Second Schaw Statutes were signed on 28 December 1599, at Holyroodhouse and consisted of fourteen separate statutes. Some of these were addressed specifically toLodge Mother Kilwinning

Lodge Mother Kilwinning is a Masonic Lodge in Kilwinning, Scotland, under the auspices of the Grand Lodge of Scotland. It is number 0 (referred to as "nothing" and not zero) on the Roll, and is reputed to be the oldest Lodge not only in Scotlan ...

, others to the lodges of Scotland in general. Kilwinning Lodge was given regional authority for west Scotland, its previous practices were confirmed, various administrative functions were specified and the officials of the lodge were enjoined to ensure that all craft fellows and apprentices "tak tryall of the art of memorie". More generally, rules were laid down for proper record keeping of the lodges, with specific fees being laid down.

The statutes state that Kilwinning was the head and second lodge in Scotland. This seems to relate to the fact that Kilwinning claimed precedence as the first lodge in Scotland, but that in Schaw's scheme of things, the Edinburgh Lodge would be most important followed by Kilwinning and then Stirling. David Stevenson argues that the Second Schaw statutes dealt with the response from within the craft to his first statutes, whereby various traditions were mobilised against his innovations, particularly from Kilwinning.

The reference to the art of memory

The art of memory (Latin: ''ars memoriae'') is any of a number of loosely associated mnemonic principles and techniques used to organize memory impressions, improve recall, and assist in the combination and 'invention' of ideas. An alternative ...

may be taken as a direct reference to renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

esotericism

Western esotericism, also known as esotericism, esoterism, and sometimes the Western mystery tradition, is a term scholars use to categorise a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements that developed within Western society. These ideas ...

. William Fowler, the poet, who had been a colleague of Schaw both in his trip to Denmark and at Dunfermline, in Anne of Denmark's household, had instructed both the King and Queen in the technique. Indeed, Fowler had met Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno

Giordano Bruno (; ; la, Iordanus Brunus Nolanus; born Filippo Bruno, January or February 1548 – 17 February 1600) was an Italian philosopher, mathematician, poet, cosmological theorist, and Hermetic occultist. He is known for his cosmolog ...

at the house of Michel de Castelnau in London in the 1580s. The art of memory constituted an important element of Bruno's magical system.

The statutes also address practical matters like health & safety concerns while working at heights. In his eighteenth article Schaw recommended that;All masters or "interprisaris of warkis be verray cairfull to see thair skaffaldis and fute-gangis (platforms) surelie sett and placeit, to the effect that throw thair negligence and sleuth (laziness), na hurt or skaith cum unto persons that works at the said work, under the pain of discharging of thame thairafter to work as masters havand charge of ane work."

The Sinclair Statutes

Two letters were drawn up in 1600 and 1601 and involved the lodges of Dunfermline,St Andrews

St Andrews ( la, S. Andrea(s); sco, Saunt Aundraes; gd, Cill Rìmhinn) is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fourt ...

, Edinburgh, Aitchison's Haven and Haddington, and were signed by Schaw himself in his capacity of Master of Works (but not General Warden). They are known as the First Sinclair Statutes as they supposedly confirm the role of the lairds of Roslin as patrons and protectors of the craft. Once again it would suggest that Schaw's proposed reorganisation of the craft had encountered some problems. Indeed, it presaged an ongoing struggle between the Master of Works and the Sinclairs, which Schaw's successors in the post continued, following his death in 1602.These 'statutes' are now the property of thGrand Lodge of Antient, Free and Accepted Masons of Scotland

/ref>

External links

Summary of the Second Schaw Statutes, in ''HMC Report: Earl of Eglinton'' (London, 1885), pp. 29–30

'THE SCHAW MONUMENT', Church Monuments Society

Transcript of William Schaw's Dalkeith letter

A gold salamander jewel from the wreck of the Girona, Ulster Museum, Armada gallery

References

Bibliography

* *Glendinning, Miles, and McKechnie, Aonghus, ''Scottish Architecture'', Thames & Hudson, 2004. *Reid-Baxter, Jamie "Politics, Passion and Poetry in the Court of James VI: John Burel and his surviving works", in: Mapstone, S, Houwen, L.A.J.R., and MacDonald, A.A. (eds.) ''A Palace in the Wind: Essays on Vernacular Culture and Humanism in Late-Medieval and Renaissance'', Peeters, 2000. *Stevenson, David ''The Origins of Freemasonry: Scotland's century 1590 – 1710'', Cambridge University Press, 1988. *Williamson, Arthur H., 'Number & National Consciousness', in: Mason, Roger A., ed., ''Scots & Britons'', Folger / CUP, (1994), pp. 187–212. {{DEFAULTSORT:Schaw, William 1550s births 1602 deaths Scottish architects Masters of Work to the Crown of Scotland 16th-century Scottish people Burials at Dunfermline Abbey Court of James VI and I Household of Anne of DenmarkWilliam

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

Renaissance architecture in Scotland

People of Stirling Castle