William Lipscomb on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Nunn Lipscomb Jr. (December 9, 1919April 14, 2011) was a Nobel Prize-winning

In this area Lipscomb proposed that:

"... progress in structure determination, for new polyborane species and for substituted

In this area Lipscomb proposed that:

"... progress in structure determination, for new polyborane species and for substituted

The three-center two-electron bond is illustrated in

The three-center two-electron bond is illustrated in  Wandering atoms was a puzzle solved by Lipscomb in one of his few papers with no co-authors.

Compounds of boron and hydrogen tend to form closed cage structures.

Sometimes the atoms at the vertices of these cages move substantial distances with respect to each other.

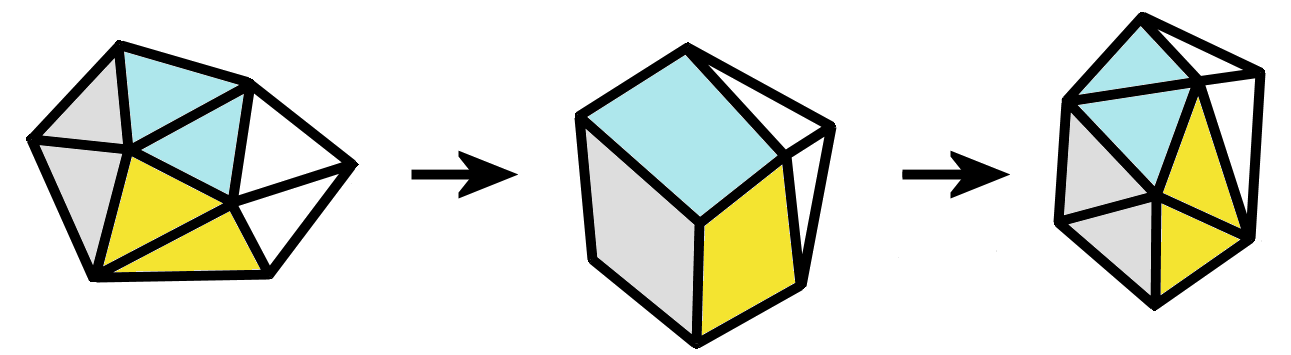

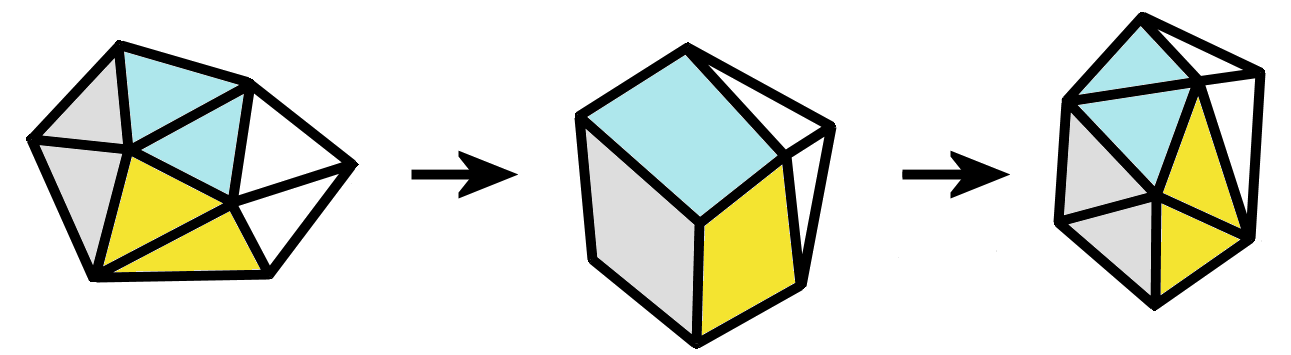

The diamond-square-diamond mechanism (diagram at left) was suggested by Lipscomb to explain this rearrangement of vertices.

Following along in the diagram at left for example in the faces shaded in blue,

a pair of triangular faces has a left-right diamond shape.

First, the bond common to these adjacent triangles breaks, forming a square,

and then the square collapses back to an up-down diamond shape

by bonding the atoms that were not bonded before.

Other researchers have discovered more about these rearrangements.

Wandering atoms was a puzzle solved by Lipscomb in one of his few papers with no co-authors.

Compounds of boron and hydrogen tend to form closed cage structures.

Sometimes the atoms at the vertices of these cages move substantial distances with respect to each other.

The diamond-square-diamond mechanism (diagram at left) was suggested by Lipscomb to explain this rearrangement of vertices.

Following along in the diagram at left for example in the faces shaded in blue,

a pair of triangular faces has a left-right diamond shape.

First, the bond common to these adjacent triangles breaks, forming a square,

and then the square collapses back to an up-down diamond shape

by bonding the atoms that were not bonded before.

Other researchers have discovered more about these rearrangements.

The B10H16 structure (diagram at right) determined by Grimes, Wang, Lewin, and Lipscomb found a bond directly between two boron atoms without terminal hydrogens, a feature not previously seen in other boron hydrides.

Lipscomb's group developed calculation methods, both empirical and from quantum mechanical theory.

Calculations by these methods produced accurate Hartree–Fock self-consistent field (SCF)

The B10H16 structure (diagram at right) determined by Grimes, Wang, Lewin, and Lipscomb found a bond directly between two boron atoms without terminal hydrogens, a feature not previously seen in other boron hydrides.

Lipscomb's group developed calculation methods, both empirical and from quantum mechanical theory.

Calculations by these methods produced accurate Hartree–Fock self-consistent field (SCF)  The

The

Carboxypeptidase A (left) was the first protein structure from Lipscomb's group. Carboxypeptidase A is a digestive enzyme, a protein that digests other proteins. It is made in the pancreas and transported in inactive form to the intestines where it is activated. Carboxypeptidase A digests by chopping off certain amino acids one-by-one from one end of a protein.

The size of this structure was ambitious. Carboxypeptidase A was a much larger molecule than anything solved previously.

Carboxypeptidase A (left) was the first protein structure from Lipscomb's group. Carboxypeptidase A is a digestive enzyme, a protein that digests other proteins. It is made in the pancreas and transported in inactive form to the intestines where it is activated. Carboxypeptidase A digests by chopping off certain amino acids one-by-one from one end of a protein.

The size of this structure was ambitious. Carboxypeptidase A was a much larger molecule than anything solved previously.

Aspartate carbamoyltransferase. (right) was the second protein structure from Lipscomb's group.

For a copy of DNA to be made, a duplicate set of its

Aspartate carbamoyltransferase. (right) was the second protein structure from Lipscomb's group.

For a copy of DNA to be made, a duplicate set of its

HaeIII

HaeIII  Human

Human

Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (left)

and its inhibitor MB06322 (CS-917)

were studied by Lipscomb's group in a collaboration, which included Metabasis Therapeutics, Inc., acquired by Ligand Pharmaceuticals in 2010, exploring the possibility of finding a treatment for

Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (left)

and its inhibitor MB06322 (CS-917)

were studied by Lipscomb's group in a collaboration, which included Metabasis Therapeutics, Inc., acquired by Ligand Pharmaceuticals in 2010, exploring the possibility of finding a treatment for

The mineral lipscombite (picture at right) was named after Professor Lipscomb by the mineralogist John Gruner who first made it artificially.

Low-temperature x-ray diffraction was pioneered in Lipscomb's laboratory at about the same time as parallel work in Isadore Fankuchen's laboratory at the then Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn.

Lipscomb began by studying compounds of nitrogen, oxygen, fluorine, and other substances that are solid only below liquid nitrogen temperatures, but other advantages eventually made low-temperatures a normal procedure.

Keeping the crystal cold during data collection produces a less-blurry 3-D electron-density map because the atoms have less thermal motion. Crystals may yield good data in the x-ray beam longer because x-ray damage may be reduced during data collection and because the solvent may evaporate more slowly, which for example may be important for large biochemical molecules whose crystals often have a high percentage of water.

Other important compounds were studied by Lipscomb and his students.

Among these are

The mineral lipscombite (picture at right) was named after Professor Lipscomb by the mineralogist John Gruner who first made it artificially.

Low-temperature x-ray diffraction was pioneered in Lipscomb's laboratory at about the same time as parallel work in Isadore Fankuchen's laboratory at the then Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn.

Lipscomb began by studying compounds of nitrogen, oxygen, fluorine, and other substances that are solid only below liquid nitrogen temperatures, but other advantages eventually made low-temperatures a normal procedure.

Keeping the crystal cold during data collection produces a less-blurry 3-D electron-density map because the atoms have less thermal motion. Crystals may yield good data in the x-ray beam longer because x-ray damage may be reduced during data collection and because the solvent may evaporate more slowly, which for example may be important for large biochemical molecules whose crystals often have a high percentage of water.

Other important compounds were studied by Lipscomb and his students.

Among these are

"Reflections"

on Linus Pauling: Video of a talk by Lipscomb. See especially the "Linus and Me" section.

in brief audio clips by Lipscomb, which include his attempt to save the life of Elizabeth Swingle.

of the Swingle accident.

Scientific Character of W. Lipscomb

Curriculum Vitae, publication list, science humor, Nobel Prize scrapbook, scientific aggression, family stories, portraits, eulogy. *

Douglas C. Rees, "William N. Lipscomb", Biographical Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences (2019)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lipscomb, William 1919 births 2011 deaths American chemists American Nobel laureates California Institute of Technology alumni Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Harvard University faculty Theoretical chemists Inorganic chemists Members of the International Academy of Quantum Molecular Science Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Nobel laureates in Chemistry Scientists from Cleveland People from Lexington, Kentucky Sayre School alumni University of Kentucky alumni University of Minnesota faculty Deaths from pneumonia in Massachusetts Presidents of the American Crystallographic Association

American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

inorganic

In chemistry, an inorganic compound is typically a chemical compound that lacks carbon–hydrogen bonds, that is, a compound that is not an organic compound. The study of inorganic compounds is a subfield of chemistry known as ''inorganic chemist ...

and organic

Organic may refer to:

* Organic, of or relating to an organism, a living entity

* Organic, of or relating to an anatomical organ

Chemistry

* Organic matter, matter that has come from a once-living organism, is capable of decay or is the product ...

chemist working in nuclear magnetic resonance

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) is a physical phenomenon in which nuclei in a strong constant magnetic field are perturbed by a weak oscillating magnetic field (in the near field) and respond by producing an electromagnetic signal with a ...

, theoretical chemistry

Theoretical chemistry is the branch of chemistry which develops theoretical generalizations that are part of the theoretical arsenal of modern chemistry: for example, the concepts of chemical bonding, chemical reaction, valence, the surface o ...

, boron chemistry, and biochemistry

Biochemistry or biological chemistry is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology and ...

.

Biography

Overview

Lipscomb was born inCleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the United States, U.S. U.S. state, state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County, Ohio, Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along ...

, Ohio

Ohio () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Of the List of states and territories of the United States, fifty U.S. states, it is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 34th-l ...

. His family moved to Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington is a city in Kentucky, United States that is the county seat of Fayette County. By population, it is the second-largest city in Kentucky and 57th-largest city in the United States. By land area, it is the country's 28th-largest ...

in 1920, and he lived there until he received his Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University o ...

degree in Chemistry at the University of Kentucky

The University of Kentucky (UK, UKY, or U of K) is a public land-grant research university in Lexington, Kentucky. Founded in 1865 by John Bryan Bowman as the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Kentucky, the university is one of the state ...

in 1941. He went on to earn his Doctor of Philosophy

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, Ph.D., or DPhil; Latin: or ') is the most common degree at the highest academic level awarded following a course of study. PhDs are awarded for programs across the whole breadth of academic fields. Because it is ...

degree in Chemistry from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in 1946.

From 1946 to 1959 he taught at the University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota, formally the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, (UMN Twin Cities, the U of M, or Minnesota) is a public land-grant research university in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States. ...

. From 1959 to 1990 he was a professor of chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the elements that make up matter to the compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions: their composition, structure, proper ...

at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

, where he was a professor emeritus

''Emeritus'' (; female: ''emerita'') is an adjective used to designate a retired chair, professor, pastor, bishop, pope, director, president, prime minister, rabbi, emperor, or other person who has been "permitted to retain as an honorary title ...

since 1990.

Lipscomb was married to the former Mary Adele Sargent from 1944 to 1983. They had three children, one of whom lived only a few hours.

He married Jean Evans in 1983. They had one adopted daughter.

Lipscomb resided in Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. As part of the Boston metropolitan area, the cities population of the 2020 U.S. census was 118,403, making it the fourth most populous city in the state, behind Boston, ...

until his death in 2011 from pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severit ...

.

Early years

"My early home environment ... stressed personal responsibility and self reliance. Independence was encouraged especially in the early years when my mother taught music and when my father's medical practice occupied most of his time." In grade school Lipscomb collected animals, insects, pets, rocks, and minerals. Interest in astronomy led him to visitor nights at the Observatory of the University of Kentucky, where Prof. H. H. Downing gave him a copy of Baker's ''Astronomy.'' Lipscomb credits gaining many intuitive physics concepts from this book and from his conversations with Downing, who became Lipscomb's lifelong friend. The young Lipscomb participated in other projects, such as Morse-coded messages over wires andcrystal radio

A crystal radio receiver, also called a crystal set, is a simple radio receiver, popular in the early days of radio. It uses only the power of the received radio signal to produce sound, needing no external power. It is named for its most imp ...

sets, with five nearby friends who became physicists, physicians, and an engineer.

At age of 12, Lipscomb was given a small Gilbert chemistry set. He expanded it by ordering apparatus and chemicals from suppliers and by using his father's privilege as a physician to purchase chemicals at the local drugstore at a discount. Lipscomb made his own fireworks and entertained visitors with color changes, odors, and explosions. His mother questioned his home chemistry hobby only once, when he attempted to isolate a large amount of urea

Urea, also known as carbamide, is an organic compound with chemical formula . This amide has two amino groups (–) joined by a carbonyl functional group (–C(=O)–). It is thus the simplest amide of carbamic acid.

Urea serves an important ...

from urine

Urine is a liquid by-product of metabolism in humans and in many other animals. Urine flows from the kidneys through the ureters to the urinary bladder. Urination results in urine being excreted from the body through the urethra.

Cellul ...

.

Lipscomb credits perusing the large medical texts in his physician father's library and the influence of Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling (; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist, biochemist, chemical engineer, peace activist, author, and educator. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific topi ...

years later to his undertaking biochemical studies in his later years. Had Lipscomb become a physician like his father, he would have been the fourth physician in a row along the Lipscomb male line.

The source for this subsection, except as noted, is Lipscomb's autobiographical sketch.

Education

Lipscomb's high-school chemistry teacher, Frederick Jones, gave Lipscomb his college books onorganic

Organic may refer to:

* Organic, of or relating to an organism, a living entity

* Organic, of or relating to an anatomical organ

Chemistry

* Organic matter, matter that has come from a once-living organism, is capable of decay or is the product ...

, analytical, and general chemistry

General chemistry (sometimes referred to as "gen chem") is offered by colleges and universities as an introductory level chemistry course usually taken by students during their first year. The course is usually run with a concurrent lab section tha ...

, and asked only that Lipscomb take the examinations.

During the class lectures, Lipscomb in the back of the classroom did research that he thought was original (but he later found was not): the preparation of hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-to ...

from sodium formate (or sodium oxalate

Sodium oxalate, or disodium oxalate, is the sodium salt of oxalic acid with the formula Na2C2O4. It is a white, crystalline, odorless solid, that decomposes above 290 °C.

Disodium oxalate can act as a reducing agent, and it may be used as a pr ...

) and sodium hydroxide

Sodium hydroxide, also known as lye and caustic soda, is an inorganic compound with the formula NaOH. It is a white solid ionic compound consisting of sodium cations and hydroxide anions .

Sodium hydroxide is a highly caustic base and al ...

.

He took care to include gas analyses and to search for probable side reaction

A side reaction is a chemical reaction that occurs at the same time as the actual main reaction, but to a lesser extent. It leads to the formation of by-product, so that the yield of main product is reduced:

: + B ->[] P1

: + C ->[] P2

P1 is th ...

s.

Lipscomb later had a high-school physics course and took first prize in the state contest on that subject. He also became very interested in special relativity.

In college at the University of Kentucky Lipscomb had a music scholarship.

He pursued independent study there, reading Dushman' s ''Elements of Quantum Mechanics'', the University of Pittsburgh

The University of Pittsburgh (Pitt) is a public state-related research university in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The university is composed of 17 undergraduate and graduate schools and colleges at its urban Pittsburgh campus, home to the univers ...

Physics Staff's ''An Outline of Atomic Physics'', and Pauling's ''The Nature of the Chemical Bond and the Structure of Molecules and Crystals.''

Prof. Robert H. Baker suggested that Lipscomb research the direct preparation of derivatives of alcohol

Alcohol most commonly refers to:

* Alcohol (chemistry), an organic compound in which a hydroxyl group is bound to a carbon atom

* Alcohol (drug), an intoxicant found in alcoholic drinks

Alcohol may also refer to:

Chemicals

* Ethanol, one of sev ...

s from dilute aqueous solution

An aqueous solution is a solution in which the solvent is water. It is mostly shown in chemical equations by appending (aq) to the relevant chemical formula. For example, a solution of table salt, or sodium chloride (NaCl), in water would be r ...

without first separating the alcohol and water, which led to Lipscomb's first publication.

For graduate school Lipscomb chose Caltech, which offered him a teaching assistantship in Physics at $20/month. He turned down more money from Northwestern University

Northwestern University is a private research university in Evanston, Illinois. Founded in 1851, Northwestern is the oldest chartered university in Illinois and is ranked among the most prestigious academic institutions in the world.

Charte ...

, which offered a research assistantship at $150/month. Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

rejected Lipscomb's application in a letter written by Nobel prizewinner Prof. Harold Urey

Harold Clayton Urey ( ; April 29, 1893 – January 5, 1981) was an American physical chemist whose pioneering work on isotopes earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1934 for the discovery of deuterium. He played a significant role in th ...

.

At Caltech Lipscomb intended to study theoretical quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is a fundamental theory in physics that provides a description of the physical properties of nature at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles. It is the foundation of all quantum physics including quantum chemistry, ...

with Prof. W. V. Houston in the Physics Department, but after one semester switched to the Chemistry Department under the

influence of Prof. Linus Pauling. World War II work divided Lipscomb's time in graduate school beyond his other thesis work, as he partly analyzed smoke particle size, but mostly worked with nitroglycerin

Nitroglycerin (NG), (alternative spelling of nitroglycerine) also known as trinitroglycerin (TNG), nitro, glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), or 1,2,3-trinitroxypropane, is a dense, colorless, oily, explosive liquid most commonly produced by nitrating g ...

–nitrocellulose

Nitrocellulose (also known as cellulose nitrate, flash paper, flash cotton, guncotton, pyroxylin and flash string, depending on form) is a highly flammable compound formed by nitrating cellulose through exposure to a mixture of nitric acid and ...

propellants, which involved handling vials of pure nitroglycerin on many occasions.

Brief audio clips by Lipscomb about his war work may be found from the External Links

An internal link is a type of hyperlink on a web page to another page or resource, such as an image or document, on the same website or domain.

Hyperlinks are considered either "external" or "internal" depending on their target or destination ...

section at the bottom of this page, past the References.

The source for this subsection, except as noted, is Lipscomb's autobiographical sketch.

Later years

The Colonel is how Lipscomb's students referred to him, directly addressing him as Colonel. "His first doctoral student, Murray Vernon King, pinned the label on him, and it was quickly adopted by other students, who wanted to use an appellation that showed informal respect. ... Lipscomb's Kentucky origins as the rationale for the designation." Some years later in 1973 Lipscomb was made a member of theHonorable Order of Kentucky Colonels

The Honorable Order of Kentucky Colonels also known as "Kentucky Colonels" or "HOKC" is a charitable, non-profit 501(c)(3) organization engaged in collective philanthropy for Kentuckians on the behalf of thousands of who have received a Kentu ...

.

Lipscomb, along with several other Nobel laureates, was a regular presenter at the annual Ig Nobel Awards Ceremony, last doing so (in a wheelchair) on September 30, 2010.

Scientific studies

Lipscomb worked in three main areas, nuclear magnetic resonance and the chemical shift, boron chemistry and the nature of the chemical bond, and large biochemical molecules. These areas overlap in time and share some scientific techniques. In at least the first two of these areas Lipscomb gave himself a big challenge likely to fail, and then plotted a course of intermediate goals.Nuclear magnetic resonance and the chemical shift

In this area Lipscomb proposed that:

"... progress in structure determination, for new polyborane species and for substituted

In this area Lipscomb proposed that:

"... progress in structure determination, for new polyborane species and for substituted borane

Trihydridoboron, also known as borane or borine, is an unstable and highly reactive molecule with the chemical formula . The preparation of borane carbonyl, BH3(CO), played an important role in exploring the chemistry of boranes, as it indicated ...

s and carborane

Carboranes are electron-delocalized (non-classically bonded) clusters composed of boron, carbon and hydrogen atoms.Grimes, R. N., ''Carboranes 3rd Ed.'', Elsevier, Amsterdam and New York (2016), . Like many of the related boron hydrides, these c ...

s, would be greatly accelerated if the oron-11nuclear magnetic resonance

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) is a physical phenomenon in which nuclei in a strong constant magnetic field are perturbed by a weak oscillating magnetic field (in the near field) and respond by producing an electromagnetic signal with a ...

spectra, rather than X-ray diffraction

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to diffract into many specific directions. By measuring the angles ...

, could be used."

This goal was partially achieved, although X-ray diffraction is still necessary to determine many such atomic structures. The diagram at right shows a typical nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrum of a borane molecule.

Lipscomb investigated, "... the carboranes, C2B10H12, and the sites of electrophilic attack on these compounds using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. This work led to ipscomb's publication of a comprehensivetheory of chemical shifts. The calculations provided the first accurate values for the constants that describe the behavior of several types of molecules in magnetic or electric fields."

Much of this work is summarized in a book by Gareth Eaton and William Lipscomb, ''NMR Studies of Boron Hydrides and Related Compounds'', one of Lipscomb's two books.

Boron chemistry and the nature of the chemical bond

In this area Lipscomb originally intended a more ambitious project: "My original intention in the late 1940s was to spend a few years understanding theborane

Trihydridoboron, also known as borane or borine, is an unstable and highly reactive molecule with the chemical formula . The preparation of borane carbonyl, BH3(CO), played an important role in exploring the chemistry of boranes, as it indicated ...

s, and then to discover a systematic valence description of the vast numbers of electron deficient intermetallic

An intermetallic (also called an intermetallic compound, intermetallic alloy, ordered intermetallic alloy, and a long-range-ordered alloy) is a type of metallic alloy that forms an ordered solid-state compound between two or more metallic eleme ...

compounds. I have made little progress toward this latter objective. Instead, the field of boron

Boron is a chemical element with the symbol B and atomic number 5. In its crystalline form it is a brittle, dark, lustrous metalloid; in its amorphous form it is a brown powder. As the lightest element of the '' boron group'' it has t ...

chemistry has grown enormously, and a systematic understanding of some of its complexities has now begun."

Examples of these intermetallic compounds are KHg13 and Cu5Zn7. Of perhaps 24,000 of such compounds the structures of only 4,000 are known (in 2005) and we cannot predict structures for the others, because we do not sufficiently understand the nature of the chemical bond.

This study was not successful, in part because the calculation time required for intermetallic compounds was out of reach in the 1960s, but intermediate goals involving boron bonding were achieved, sufficient to be awarded a Nobel Prize.

diborane

Diborane(6), generally known as diborane, is the chemical compound with the formula B2H6. It is a toxic, colorless, and pyrophoric gas with a repulsively sweet odor. Diborane is a key boron compound with a variety of applications. It has attracte ...

(diagrams at right).

In an ordinary covalent bond a pair of electrons bonds two atoms together, one at either end of the bond, the diboare B-H bonds for example at the left and right in the illustrations.

In three-center two-electron bond a pair of electrons bonds three atoms (a boron atom at either end and a hydrogen atom in the middle), the diborane B-H-B bonds for example at the top and bottom of the illustrations.

Lipscomb's group did not propose or discover the three-center two-electron bond,

nor did they develop formulas that give the proposed mechanism.

In 1943, Longuet-Higgins, while still an undergraduate at Oxford, was the first to explain

the structure and bonding of the boron hydrides. The paper reporting the work, written with his tutor R. P. Bell,

also reviews the history of the subject beginning with the work of Dilthey.

Shortly after, in 1947 and 1948, experimental spectroscopic work was performed by Price

that confirmed Longuet-Higgins' structure for diborane. The structure was re-confirmed by electron diffraction measurement in 1951 by K. Hedberg and V. Schomaker, with the confirmation of the structure shown in the schemes on this page. Lipscomb and his graduate students further determined the molecular structure of borane

Trihydridoboron, also known as borane or borine, is an unstable and highly reactive molecule with the chemical formula . The preparation of borane carbonyl, BH3(CO), played an important role in exploring the chemistry of boranes, as it indicated ...

s (compounds of boron and hydrogen) using X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to diffract into many specific directions. By measuring the angles ...

in the 1950s and developed theories to explain their bond

Bond or bonds may refer to:

Common meanings

* Bond (finance), a type of debt security

* Bail bond, a commercial third-party guarantor of surety bonds in the United States

* Chemical bond, the attraction of atoms, ions or molecules to form chemical ...

s. Later he applied the same methods to related problems, including the structure of carborane

Carboranes are electron-delocalized (non-classically bonded) clusters composed of boron, carbon and hydrogen atoms.Grimes, R. N., ''Carboranes 3rd Ed.'', Elsevier, Amsterdam and New York (2016), . Like many of the related boron hydrides, these c ...

s (compounds of carbon, boron, and hydrogen). Longuet-Higgins

and Roberts

discussed the electronic structure of an icosahedron of boron atoms and of the borides MB6. The mechanism of the three-center two-electron bond was also discussed in a later paper by Longuet-Higgins, and an essentially equivalent mechanism was proposed by Eberhardt, Crawford, and Lipscomb.

Lipscomb's group also achieved an understanding of it through electron orbital calculations using formulas by Edmiston and Ruedenberg and by Boys.

The Eberhardt, Crawford, and Lipscomb paper discussed above also devised the "styx number" method to catalog certain kinds of boron-hydride bonding configurations.

Wandering atoms was a puzzle solved by Lipscomb in one of his few papers with no co-authors.

Compounds of boron and hydrogen tend to form closed cage structures.

Sometimes the atoms at the vertices of these cages move substantial distances with respect to each other.

The diamond-square-diamond mechanism (diagram at left) was suggested by Lipscomb to explain this rearrangement of vertices.

Following along in the diagram at left for example in the faces shaded in blue,

a pair of triangular faces has a left-right diamond shape.

First, the bond common to these adjacent triangles breaks, forming a square,

and then the square collapses back to an up-down diamond shape

by bonding the atoms that were not bonded before.

Other researchers have discovered more about these rearrangements.

Wandering atoms was a puzzle solved by Lipscomb in one of his few papers with no co-authors.

Compounds of boron and hydrogen tend to form closed cage structures.

Sometimes the atoms at the vertices of these cages move substantial distances with respect to each other.

The diamond-square-diamond mechanism (diagram at left) was suggested by Lipscomb to explain this rearrangement of vertices.

Following along in the diagram at left for example in the faces shaded in blue,

a pair of triangular faces has a left-right diamond shape.

First, the bond common to these adjacent triangles breaks, forming a square,

and then the square collapses back to an up-down diamond shape

by bonding the atoms that were not bonded before.

Other researchers have discovered more about these rearrangements.

The B10H16 structure (diagram at right) determined by Grimes, Wang, Lewin, and Lipscomb found a bond directly between two boron atoms without terminal hydrogens, a feature not previously seen in other boron hydrides.

Lipscomb's group developed calculation methods, both empirical and from quantum mechanical theory.

Calculations by these methods produced accurate Hartree–Fock self-consistent field (SCF)

The B10H16 structure (diagram at right) determined by Grimes, Wang, Lewin, and Lipscomb found a bond directly between two boron atoms without terminal hydrogens, a feature not previously seen in other boron hydrides.

Lipscomb's group developed calculation methods, both empirical and from quantum mechanical theory.

Calculations by these methods produced accurate Hartree–Fock self-consistent field (SCF) molecular orbital

In chemistry, a molecular orbital is a mathematical function describing the location and wave-like behavior of an electron in a molecule. This function can be used to calculate chemical and physical properties such as the probability of find ...

s and were used to study boranes and carboranes.

The

The ethane

Ethane ( , ) is an organic chemical compound with chemical formula . At standard temperature and pressure, ethane is a colorless, odorless gas. Like many hydrocarbons, ethane is isolated on an industrial scale from natural gas and as a petroc ...

barrier to rotation (diagram at left) was first calculated accurately by Pitzer and Lipscomb using the Hartree–Fock (SCF) method.

Lipscomb's calculations continued to a detailed examination of partial bonding through "... theoretical studies of multicentered chemical bonds including both delocalized and localized molecular orbitals."

This included "... proposed molecular orbital descriptions in which the bonding electrons are delocalized over the whole molecule."

"Lipscomb and his coworkers developed the idea of transferability of atomic properties, by which approximate theories for complex molecules are developed from more exact calculations for simpler but chemically related molecules,..."

Subsequent Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

winner Roald Hoffmann

Roald Hoffmann (born Roald Safran; July 18, 1937) is a Polish-American theoretical chemist who won the 1981 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He has also published plays and poetry. He is the Frank H. T. Rhodes Professor of Humane Letters, Emeritus, at ...

was a doctoral student

in Lipscomb's laboratory.

Under Lipscomb's direction the Extended Hückel method of molecular orbital calculation was developed by Lawrence Lohr and by Roald Hoffmann. This method was later extended by Hoffman.

In Lipscomb's laboratory this method was reconciled with self-consistent field (SCF) theory by Newton and by Boer.

Noted boron chemist M. Frederick Hawthorne conducted early and continuing research with Lipscomb.

Much of this work is summarized in a book by Lipscomb, ''Boron Hydrides'', one of Lipscomb's two books.

The 1976 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then "M ...

was awarded to Lipscomb "for his studies on the structure of boranes illuminating problems of chemical bonding".

In a way this continued work on the nature of the chemical bond by his doctoral advisor at the California Institute of Technology, Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling (; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist, biochemist, chemical engineer, peace activist, author, and educator. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific topi ...

, who was awarded the 1954 Nobel Prize in Chemistry "for his research into the nature of the chemical bond and its application to the elucidation of the structure of complex substances."

The source for about half of this section is Lipscomb's Nobel Lecture.

Large biological molecule structure and function

Lipscomb's later research focused on the atomic structure ofprotein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, res ...

s, particularly how enzymes

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. ...

work.

His group used x-ray diffraction to solve the three-dimensional structure of these proteins to atomic resolution, and then to analyze the atomic detail of how the molecules work.

The images below are of Lipscomb's structures from the Protein Data Bank displayed in simplified form with atomic detail suppressed. Proteins are chains of amino acids, and the continuous ribbon shows the trace of the chain with, for example, several amino acids for each turn of a helix.

Carboxypeptidase A (left) was the first protein structure from Lipscomb's group. Carboxypeptidase A is a digestive enzyme, a protein that digests other proteins. It is made in the pancreas and transported in inactive form to the intestines where it is activated. Carboxypeptidase A digests by chopping off certain amino acids one-by-one from one end of a protein.

The size of this structure was ambitious. Carboxypeptidase A was a much larger molecule than anything solved previously.

Carboxypeptidase A (left) was the first protein structure from Lipscomb's group. Carboxypeptidase A is a digestive enzyme, a protein that digests other proteins. It is made in the pancreas and transported in inactive form to the intestines where it is activated. Carboxypeptidase A digests by chopping off certain amino acids one-by-one from one end of a protein.

The size of this structure was ambitious. Carboxypeptidase A was a much larger molecule than anything solved previously.

Aspartate carbamoyltransferase. (right) was the second protein structure from Lipscomb's group.

For a copy of DNA to be made, a duplicate set of its

Aspartate carbamoyltransferase. (right) was the second protein structure from Lipscomb's group.

For a copy of DNA to be made, a duplicate set of its nucleotide

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecu ...

s is required. Aspartate carbamoyltransferase performs a step in building the pyrimidine

Pyrimidine (; ) is an aromatic, heterocyclic, organic compound similar to pyridine (). One of the three diazines (six-membered heterocyclics with two nitrogen atoms in the ring), it has nitrogen atoms at positions 1 and 3 in the ring. The othe ...

nucleotides (cytosine

Cytosine () ( symbol C or Cyt) is one of the four nucleobases found in DNA and RNA, along with adenine, guanine, and thymine ( uracil in RNA). It is a pyrimidine derivative, with a heterocyclic aromatic ring and two substituents attached ( ...

and thymidine

Thymidine (symbol dT or dThd), also known as deoxythymidine, deoxyribosylthymine, or thymine deoxyriboside, is a pyrimidine deoxynucleoside. Deoxythymidine is the DNA nucleoside T, which pairs with deoxyadenosine (A) in double-stranded DNA. ...

). Aspartate carbamoyltransferase also ensures that just the right amount of pyrimidine nucleotides is available, as activator and inhibitor molecules attach to aspartate carbamoyltransferase to speed it up and to slow it down.

Aspartate carbamoyltransferase is a complex of twelve molecules.

Six large catalytic molecules in the interior do the work, and six small regulatory molecules on the outside control how fast the catalytic units work.

The size of this structure was ambitious. Aspartate carbamoyltransferase was a much larger molecule than anything solved previously.

Leucine aminopeptidase

Leucyl aminopeptidases (, ''leucine aminopeptidase'', ''LAPs'', ''leucyl peptidase'', ''peptidase S'', ''cytosol aminopeptidase'', ''cathepsin III'', ''L-leucine aminopeptidase'', ''leucinaminopeptidase'', ''leucinamide aminopeptidase'', ''FTBL pr ...

, (left) a little like carboxypeptidase A, chops off certain amino acids one-by-one from one end of a protein or peptide

Peptides (, ) are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Long chains of amino acids are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty amino acids are called oligopeptides, and include dipeptides, tripeptides, and tetrapeptides. ...

.

HaeIII

HaeIII methyltransferase

Methyltransferases are a large group of enzymes that all Methylation, methylate their substrates but can be split into several subclasses based on their structural features. The most common class of methyltransferases is class I, all of which co ...

(right)

binds to DNA where it methylates (adds a methy group to)

it.

Human

Human interferon

Interferons (IFNs, ) are a group of signaling proteins made and released by host cells in response to the presence of several viruses. In a typical scenario, a virus-infected cell will release interferons causing nearby cells to heighten th ...

beta (left)

is released by lymphocyte

A lymphocyte is a type of white blood cell (leukocyte) in the immune system of most vertebrates. Lymphocytes include natural killer cells (which function in cell-mediated, cytotoxic innate immunity), T cells (for cell-mediated, cytotoxic a ...

s in response to pathogen

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a g ...

s to trigger the immune system

The immune system is a network of biological processes that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, from viruses to parasitic worms, as well as cancer cells and objects such as wood splinte ...

.

Chorismate mutase

In enzymology, chorismate mutase () is an enzyme that catalyzes the chemical reaction for the conversion of chorismate to prephenate in the pathway to the production of phenylalanine and tyrosine, also known as the shikimate pathway.

Hence, this ...

(right)

catalyzes (speeds up) the production of the amino acids phenylalanine

Phenylalanine (symbol Phe or F) is an essential α-amino acid with the formula . It can be viewed as a benzyl group substituted for the methyl group of alanine, or a phenyl group in place of a terminal hydrogen of alanine. This essential amin ...

and tyrosine

-Tyrosine or tyrosine (symbol Tyr or Y) or 4-hydroxyphenylalanine is one of the 20 standard amino acids that are used by cells to synthesize proteins. It is a non-essential amino acid with a polar side group. The word "tyrosine" is from the G ...

.

Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (left)

and its inhibitor MB06322 (CS-917)

were studied by Lipscomb's group in a collaboration, which included Metabasis Therapeutics, Inc., acquired by Ligand Pharmaceuticals in 2010, exploring the possibility of finding a treatment for

Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (left)

and its inhibitor MB06322 (CS-917)

were studied by Lipscomb's group in a collaboration, which included Metabasis Therapeutics, Inc., acquired by Ligand Pharmaceuticals in 2010, exploring the possibility of finding a treatment for type 2 diabetes

Type 2 diabetes, formerly known as adult-onset diabetes, is a form of diabetes mellitus that is characterized by high blood sugar, insulin resistance, and relative lack of insulin. Common symptoms include increased thirst, frequent urinatio ...

, as the MB06322 inhibitor slows the production of sugar by fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase.

Lipscomb's group also contributed to an understanding of

concanavalin A (low resolution structure),

glucagon

Glucagon is a peptide hormone, produced by alpha cells of the pancreas. It raises concentration of glucose and fatty acids in the bloodstream, and is considered to be the main catabolic hormone of the body. It is also used as a medication to tre ...

, and

carbonic anhydrase

The carbonic anhydrases (or carbonate dehydratases) () form a family of enzymes that catalyze the interconversion between carbon dioxide and water and the dissociated ions of carbonic acid (i.e. bicarbonate and hydrogen ions). The active sit ...

(theoretical studies).

Subsequent Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

winner Thomas A. Steitz

was a doctoral student in Lipscomb's laboratory.

Under Lipscomb's direction, after the training task of determining the structure of the small molecule methyl ethylene phosphate, Steitz made contributions to determining the atomic structures of carboxypeptidase A

and aspartate carbamoyltransferase.

Steitz was awarded the 2009 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then "M ...

for determining the even larger structure of the large 50S ribosomal subunit, leading to an understanding of possible medical treatments.

Subsequent Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

winner Ada Yonath, who shared the 2009 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Thomas A. Steitz and Venkatraman Ramakrishnan

Venkatraman Ramakrishnan (born 1952) is an Indian-born British and American structural biologist who shared the 2009 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Thomas A. Steitz and Ada Yonath, "for studies of the structure and function of the ribosome" ...

, spent some time in Lipscomb's lab where both she and Steitz were inspired to pursue later their own very large structures. This was while she was a postdoctoral student at MIT in 1970.

Other results

The mineral lipscombite (picture at right) was named after Professor Lipscomb by the mineralogist John Gruner who first made it artificially.

Low-temperature x-ray diffraction was pioneered in Lipscomb's laboratory at about the same time as parallel work in Isadore Fankuchen's laboratory at the then Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn.

Lipscomb began by studying compounds of nitrogen, oxygen, fluorine, and other substances that are solid only below liquid nitrogen temperatures, but other advantages eventually made low-temperatures a normal procedure.

Keeping the crystal cold during data collection produces a less-blurry 3-D electron-density map because the atoms have less thermal motion. Crystals may yield good data in the x-ray beam longer because x-ray damage may be reduced during data collection and because the solvent may evaporate more slowly, which for example may be important for large biochemical molecules whose crystals often have a high percentage of water.

Other important compounds were studied by Lipscomb and his students.

Among these are

The mineral lipscombite (picture at right) was named after Professor Lipscomb by the mineralogist John Gruner who first made it artificially.

Low-temperature x-ray diffraction was pioneered in Lipscomb's laboratory at about the same time as parallel work in Isadore Fankuchen's laboratory at the then Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn.

Lipscomb began by studying compounds of nitrogen, oxygen, fluorine, and other substances that are solid only below liquid nitrogen temperatures, but other advantages eventually made low-temperatures a normal procedure.

Keeping the crystal cold during data collection produces a less-blurry 3-D electron-density map because the atoms have less thermal motion. Crystals may yield good data in the x-ray beam longer because x-ray damage may be reduced during data collection and because the solvent may evaporate more slowly, which for example may be important for large biochemical molecules whose crystals often have a high percentage of water.

Other important compounds were studied by Lipscomb and his students.

Among these are

hydrazine

Hydrazine is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a simple pnictogen hydride, and is a colourless flammable liquid with an ammonia-like odour. Hydrazine is highly toxic unless handled in solution as, for example, hydrazine ...

,

nitric oxide

Nitric oxide (nitrogen oxide or nitrogen monoxide) is a colorless gas with the formula . It is one of the principal oxides of nitrogen. Nitric oxide is a free radical: it has an unpaired electron, which is sometimes denoted by a dot in its ...

,

metal-dithiolene complexes,

methyl ethylene phosphate,

mercury amide

In organic chemistry, an amide, also known as an organic amide or a carboxamide, is a compound with the general formula , where R, R', and R″ represent organic groups or hydrogen atoms. The amide group is called a peptide bond when it i ...

s,

(NO)2,

crystalline hydrogen fluoride

Hydrogen fluoride (fluorane) is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . This colorless gas or liquid is the principal industrial source of fluorine, often as an aqueous solution called hydrofluoric acid. It is an important feedstock ...

,

Roussin's black salt,

(PCF3)5,

complexes of cyclo-octatetraene with iron tricarbonyl,

and leurocristine (Vincristine), which is used in several cancer therapies.

Positions, awards and honors

*Guggenheim Fellow

Guggenheim Fellowships are grants that have been awarded annually since by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation to those "who have demonstrated exceptional capacity for productive scholarship or exceptional creative ability in the ar ...

, 1954

* Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, a ...

in 1960.

* Member of United States National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nat ...

*Member of the Faculty Advisory Board of MIT-Harvard Research Journal

* Foreign Member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences

The Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences ( nl, Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, abbreviated: KNAW) is an organization dedicated to the advancement of science and literature in the Netherlands. The academy is housed ...

(1976)

* Nobel Prize in Chemistry

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then "M ...

(1976)

Five books and published symposia are dedicated to Lipscomb.

A complete list of Lipscomb's awards and honors is in his Curriculum Vitae.

References

External links

"Reflections"

on Linus Pauling: Video of a talk by Lipscomb. See especially the "Linus and Me" section.

in brief audio clips by Lipscomb, which include his attempt to save the life of Elizabeth Swingle.

of the Swingle accident.

Scientific Character of W. Lipscomb

Curriculum Vitae, publication list, science humor, Nobel Prize scrapbook, scientific aggression, family stories, portraits, eulogy. *

Douglas C. Rees, "William N. Lipscomb", Biographical Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences (2019)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lipscomb, William 1919 births 2011 deaths American chemists American Nobel laureates California Institute of Technology alumni Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Harvard University faculty Theoretical chemists Inorganic chemists Members of the International Academy of Quantum Molecular Science Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Nobel laureates in Chemistry Scientists from Cleveland People from Lexington, Kentucky Sayre School alumni University of Kentucky alumni University of Minnesota faculty Deaths from pneumonia in Massachusetts Presidents of the American Crystallographic Association