William Henry Perkin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir William Henry Perkin (12 March 1838 – 14 July 1907) was a British

They satisfied themselves that they might be able to scale up production of the purple substance and commercialise it as a dye, which they called mauveine. Their initial experiments indicated that it dyed

They satisfied themselves that they might be able to scale up production of the purple substance and commercialise it as a dye, which they called mauveine. Their initial experiments indicated that it dyed  Having invented the dye, Perkin was still faced with the problems of raising the capital for producing it, manufacturing it cheaply, adapting it for use in dyeing

Having invented the dye, Perkin was still faced with the problems of raising the capital for producing it, manufacturing it cheaply, adapting it for use in dyeing

William Perkin continued active research in

William Perkin continued active research in

Perkin died in 1907 of

Perkin died in 1907 of

Perkin received many honours in his lifetime. In June 1866, he was elected a

Perkin received many honours in his lifetime. In June 1866, he was elected a

"Imperial students celebrate in largest ever Postgraduate Graduation Ceremonies"

Imperial College London. Retrieved 12 March 2018

chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe t ...

and entrepreneur best known for his serendipitous discovery of the first commercial synthetic organic dye, mauveine, made from aniline

Aniline is an organic compound with the formula C6 H5 NH2. Consisting of a phenyl group attached to an amino group, aniline is the simplest aromatic amine. It is an industrially significant commodity chemical, as well as a versatile starti ...

. Though he failed in trying to synthesise quinine for the treatment of malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

, he became successful in the field of dyes after his first discovery at the age of 18.

Perkin set up a factory to produce the dye industrially. Lee Blaszczyk, professor of business history at the University of Leeds, states, "By laying the foundation for the synthetic organic chemicals industry, Perkin helped to revolutionize the world of fashion."

Early years

William Perkin was born in the East End of London, the youngest of the seven children of George Perkin, a successful carpenter. His mother, Sarah, was of Scottish descent and moved to East London as a child.UXL Encyclopedia of World Biography (2003). Accessed 18 March 2008. He was baptized in the Anglican parish church of St Paul's, Shadwell, which had been connected to James Cook, Jane Randolph Jefferson (mother ofThomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

) and John Wesley.

At the age of 14, Perkin attended the City of London School

, established =

, closed =

, type = Public school Boys' independent day school

, president =

, head_label = Headmaster

, head = Alan Bird

, chair_label = Chair of Governors

, chair = Ian Seaton

, founder = John Carpenter

, special ...

, where he was taught by Thomas Hall, who fostered his scientific talent and encouraged him to pursue a career in chemistry.

Accidental discovery of mauveine

In 1853, at the age of 15, Perkin entered the Royal College of Chemistry, now part ofImperial College London

Imperial College London (legally Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine) is a public research university in London, United Kingdom. Its history began with Prince Albert, consort of Queen Victoria, who developed his vision for a cu ...

, where he began his studies under August Wilhelm von Hofmann. At this time, chemistry was still primitive: although the major elements had been discovered and techniques to analyze the proportions of the elements in many compounds were in place, it was still a difficult proposition to determine the arrangement of the elements in compounds. Hofmann had published a hypothesis on how it might be possible to synthesise quinine, an expensive natural substance much in demand for the treatment of malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

. Having become one of Hofmann's assistants, Perkin embarked on a series of experiments to try to achieve this end.

During the Easter

Easter,Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the '' Book of Common Prayer''; "Easter Sunday", used by James Ussher''The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4'') and Samuel Pepys''The Diary of Samuel ...

vacation in 1856, Perkin performed some further experiments in the crude laboratory in his apartment on the top floor of his home in Cable Street

Cable Street is a road in the East End of London, England, with several historic landmarks nearby. It was made famous by the Battle of Cable Street in 1936.

Location

Cable Street starts near the edge of London's financial district, the City ...

in east London. It was here that he made his great accidental discovery: that aniline

Aniline is an organic compound with the formula C6 H5 NH2. Consisting of a phenyl group attached to an amino group, aniline is the simplest aromatic amine. It is an industrially significant commodity chemical, as well as a versatile starti ...

could be partly transformed into a crude mixture which, when extracted with alcohol, produced a substance with an intense purple

Purple is any of a variety of colors with hue between red and blue. In the RGB color model used in computer and television screens, purples are produced by mixing red and blue light. In the RYB color model historically used by painters, ...

colour. Perkin, who had an interest in painting and photography, immediately became enthusiastic about this result and carried out further trials with his friend Arthur Church and his brother Thomas. Since these experiments were not part of the work on quinine which had been assigned to Perkin, the trio carried them out in a hut in Perkin's garden to keep them secret from Hofmann.

They satisfied themselves that they might be able to scale up production of the purple substance and commercialise it as a dye, which they called mauveine. Their initial experiments indicated that it dyed

They satisfied themselves that they might be able to scale up production of the purple substance and commercialise it as a dye, which they called mauveine. Their initial experiments indicated that it dyed silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the ...

in a way which was stable when washed or exposed to light. They sent some samples to a dye works in Perth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth i ...

, Scotland, and received a very promising reply from the general manager of the company, Robert Pullar. Perkin filed for a patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A ...

in August 1856, when he was still only 18.

At the time, all dyes used for colouring cloth were natural substances, many of which were expensive and labour-intensive to extract—and many lacked stability, or fastness. The colour purple, which had been a mark of aristocracy and prestige since ancient times, was especially expensive and difficult to produce. Its extraction was variable and complicated, and so Perkin and his brother realised that they had discovered a possible substitute whose production could be commercially successful.

Perkin could not have chosen a better time or place for his discovery: England was the cradle of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

, largely driven by advances in the production of textiles; the science of chemistry had advanced to the point where it could have a major impact on industrial processes; and coal tar

Coal tar is a thick dark liquid which is a by-product of the production of coke and coal gas from coal. It is a type of creosote. It has both medical and industrial uses. Medicinally it is a topical medication applied to skin to treat psorias ...

, the major source of his raw material, was an abundant by-product of the process for making coal gas and coke.Michigan State University, Department of Chemistry website. Accessed 18 March 2008.

Having invented the dye, Perkin was still faced with the problems of raising the capital for producing it, manufacturing it cheaply, adapting it for use in dyeing

Having invented the dye, Perkin was still faced with the problems of raising the capital for producing it, manufacturing it cheaply, adapting it for use in dyeing cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

, gaining acceptance for it among commercial dyers, and creating public demand for it. He was active in all of these areas: he persuaded his father to put up the capital, and his brothers to partner with him to build a factory; he invented a mordant for cotton; he gave technical advice to the dyeing industry; and he publicised his invention of the dye.

Public demand was increased when a similar colour was adopted by Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

in Britain and by Empress Eugénie

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife ( empress consort), mother (empr ...

, wife of Napoleon III, in France, and when the crinoline or hooped-skirt, whose manufacture used a large quantity of cloth, became fashionable. Perkin’s mauve was cheaper than traditional, natural purple dyes and became so popular that English humourists joked about the ’mauve measles’. Everything fell into place: with hard work and lucky timing, Perkin became rich. After the discovery of mauveine, many new aniline dye

Aniline is an organic compound with the formula C6 H5 NH2. Consisting of a phenyl group attached to an amino group, aniline is the simplest aromatic amine. It is an industrially significant commodity chemical, as well as a versatile starting m ...

s appeared (some discovered by Perkin himself), and factories producing them were constructed across Europe.

Later years

William Perkin continued active research in

William Perkin continued active research in organic chemistry

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms that contain carbon atoms.Clayden, ...

for the rest of his life: he discovered and marketed other synthetic dyes

A dye is a colored substance that chemically bonds to the substrate to which it is being applied. This distinguishes dyes from pigments which do not chemically bind to the material they color. Dye is generally applied in an aqueous solution and ...

, including ''Britannia Violet'' and ''Perkin's Green''; he discovered ways to make coumarin

Coumarin () or 2''H''-chromen-2-one is an aromatic organic chemical compound with formula . Its molecule can be described as a benzene molecule with two adjacent hydrogen atoms replaced by a lactone-like chain , forming a second six-membered h ...

, one of the first synthetic raw materials of perfume

Perfume (, ; french: parfum) is a mixture of fragrant essential oils or aroma compounds (fragrances), fixatives and solvents, usually in liquid form, used to give the human body, animals, food, objects, and living-spaces an agreeable scent. Th ...

, and cinnamic acid

Cinnamic acid is an organic compound with the formula C6H5-CH=CH- COOH. It is a white crystalline compound that is slightly soluble in water, and freely soluble in many organic solvents. Classified as an unsaturated carboxylic acid, it occurs na ...

. (The reaction used to make the last became known as the Perkin reaction

The Perkin reaction is an organic reaction developed by English chemist William Henry Perkin that is used to make cinnamic acids. It gives an α,β-unsaturated aromatic acid or α-substituted β-aryl acrylic acid by the aldol condensation of a ...

.) Local lore has it that the colour of the nearby Grand Union Canal changed from week to week depending on the activity at Perkin's Greenford dyeworks.

In 1869, Perkin found a method for the commercial production from anthracene of the brilliant red dye alizarin

Alizarin (also known as 1,2-dihydroxyanthraquinone, Mordant Red 11, C.I. 58000, and Turkey Red) is an organic compound with formula that has been used throughout history as a prominent red dye, principally for dyeing textile fabrics. Historic ...

, which had been isolated and identified from madder root some forty years earlier in 1826 by the French chemist Pierre Robiquet, simultaneously with purpurin, another red dye of lesser industrial interest, but the German chemical company BASF

BASF SE () is a German multinational chemical company and the largest chemical producer in the world. Its headquarters is located in Ludwigshafen, Germany.

The BASF Group comprises subsidiaries and joint ventures in more than 80 countries ...

patented the same process one day before he did.

During the next decade, the new German Empire was rapidly eclipsing Britain as the centre of Europe's chemical industry. By the 1890s, Germany had a near-monopoly

A monopoly (from Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situation where a speci ...

on the business and Perkin was compelled to sell off his holdings and retire.

Death

Perkin died in 1907 of

Perkin died in 1907 of pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severi ...

and other complications resulting from a burst appendix. He is buried in the grounds of Christchurch, Harrow, Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a historic county in southeast England. Its area is almost entirely within the wider urbanised area of London and mostly within the ceremonial county of Greater London, with small sections in neighbour ...

.''The Leathersellers' Review 2005–06'', pp 12–14 His will was proved on 28 August 1907 at £86,231 4s. 11d. (roughly equivalent to £ in ).

Family

Perkin married Jemima Harriet, the daughter of John Lissett, in 1859, which resulted in two sons, ( William Henry Perkin Jr. andArthur George Perkin

Arthur George Perkin DSc FRS FRSE (1861–1937) was an English chemist and Professor of Colour Chemistry and Dyeing at the University of Leeds.

Life

Perkin was the second son of Sir William Henry Perkin FRS, who founded the aniline dye indu ...

). Perkin's second marriage was in 1866, to Alexandrine Caroline, daughter of Helman Mollwo. They had one son (Frederick Mollwo Perkin) and four daughters. All three sons became chemists.

Honours, awards and commemorations

Perkin received many honours in his lifetime. In June 1866, he was elected a

Perkin received many honours in his lifetime. In June 1866, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathemat ...

. In 1879, received their Royal Medal and, in 1889, their Davy Medal

The Davy Medal is awarded by the Royal Society of London "for an outstandingly important recent discovery in any branch of chemistry". Named after Humphry Davy, the medal is awarded with a monetary gift, initially of £1000 (currently £2000).

H ...

. He was knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

ed in 1906, and in the same year was awarded the first Perkin Medal

The Perkin Medal is an award given annually by the Society of Chemical Industry (American Section) to a scientist residing in America for an "innovation in applied chemistry resulting in outstanding commercial development." It is considered the ...

, established to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of his discovery of mauveine. Today, the Perkin Medal is widely acknowledged as the highest honour in the U.S. industrial chemistry and has been awarded annually by the American section of the Society of Chemical Industry.

Perkin was a Liveryman of the Leathersellers' Company for 46 years and was elected Master of the Company for the year 1896–97.

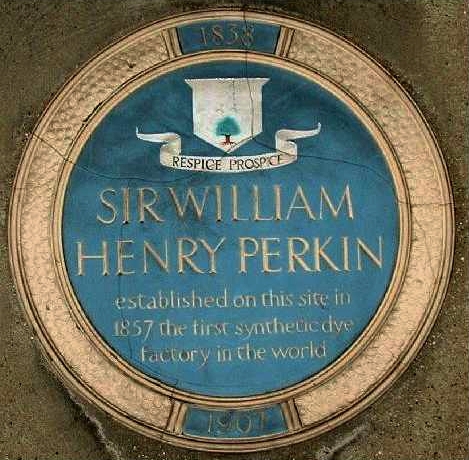

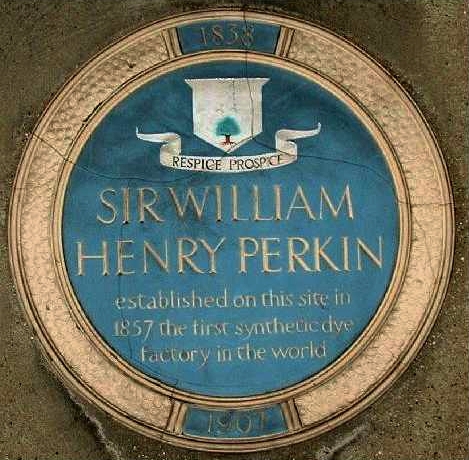

Today blue plaques mark the sites of Perkin's home in Cable Street

Cable Street is a road in the East End of London, England, with several historic landmarks nearby. It was made famous by the Battle of Cable Street in 1936.

Location

Cable Street starts near the edge of London's financial district, the City ...

, by the junction with King David Lane, and the Perkin factory in Greenford, Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a historic county in southeast England. Its area is almost entirely within the wider urbanised area of London and mostly within the ceremonial county of Greater London, with small sections in neighbour ...

.

A portrait, by Edward Railton Catterns (1838–1909), is owned by the University of Strathclyde.

On 12 March 2018, search engine Google

Google LLC () is an American Multinational corporation, multinational technology company focusing on Search Engine, search engine technology, online advertising, cloud computing, software, computer software, quantum computing, e-commerce, ar ...

showed a Google Doodle

A Google Doodle is a special, temporary alteration of the logo on Google's homepages intended to commemorate holidays, events, achievements, and notable historical figures. The first Google Doodle honored the 1998 edition of the long-running an ...

to mark Perkin's 180th Birthday.

William Perkin High School

In 2013, theWilliam Perkin Church of England High School

William Perkin Church of England High School is a coeducational secondary school and sixth form located in the Greenford area of London, England.

History

The school was established in 2013. It is a free school sponsored by the Twyford Church ...

opened in Greenford, Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a historic county in southeast England. Its area is almost entirely within the wider urbanised area of London and mostly within the ceremonial county of Greater London, with small sections in neighbour ...

. The school is operated by the Twyford Church of England Academies Trust

Twyford Church of England Academies Trust is a multi-academy trust based in West London and affiliated to the London Diocesan Board for Schools. It currently consists of four academies in the London Borough of Ealing: Twyford Church of England H ...

(which also operates Twyford Church of England High School Twyford may refer to:

Places

In the United Kingdom:

* Twyford, Berkshire

* Twyford, Buckinghamshire

* Twyford, Derbyshire, in the civil parish of Twyford and Stenson

* Twyford, Dorset, a location

* Twyford, Hampshire

* Twyford, Leicestershire

*Tw ...

). The school is named after William Perkin, and has adopted a mauve uniform and colour scheme, in tribute to his discovery of mauveine.

Imperial College London

Since 2007, whenImperial College London

Imperial College London (legally Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine) is a public research university in London, United Kingdom. Its history began with Prince Albert, consort of Queen Victoria, who developed his vision for a cu ...

gained its own Royal Charter, the Academic dress of Imperial College London features purple across the range of garments to celebrate the work of Perkin. In 2015, President of the College, Professor Alice Gast, stated that: "The colour purple symbolises the spirit of endeavour and discovery, and the risk-taking nature that characterises those with an Imperial education and training."Imperial College London. Retrieved 12 March 2018

References

Further reading

* * * Garfield, Simon, ''Mauve: How One Man Invented a Colour that Changed the World'', (2000). * Travis, Anthony S. "Perkin, Sir William Henry (1838–1907)" in the ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'', edited C. Matthew et al. Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print books ...

: 2004. .

* Farrell, Jerome, "The Master Leatherseller who Changed the World" in ''The Leathersellers' Review'' 2005–06, pp. 12–14

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Perkin, William 1838 births 1907 deaths English people of Scottish descent People from Wapping Alumni of Imperial College London 19th-century British chemists 19th-century British inventors Knights Bachelor People of the Industrial Revolution Academics of Imperial College London Chemical industry in London Textile workers Fellows of the Royal Society Royal Medal winners Deaths from pneumonia in England Scientists from London