William Gouge on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

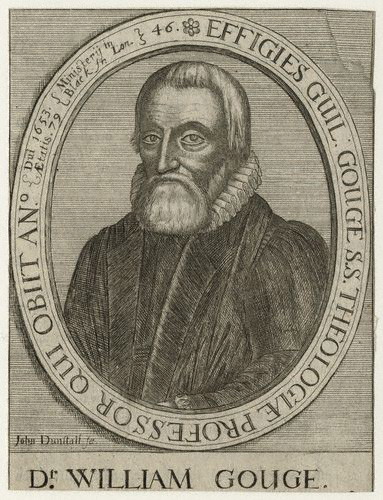

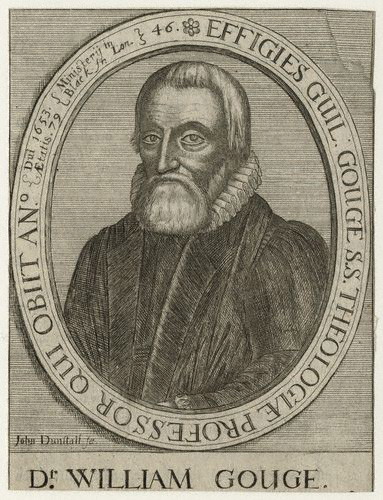

William Gouge (1575–1653) was an English

William Gouge (1575–1653) was an English

''Of Domesticall Duties'' (1622) was a popular and thorough text of its time discussing family life. It argued that the wife although above the children is below the husband and the father figure "is a king in his owne house", and was an important

''Of Domesticall Duties'' (1622) was a popular and thorough text of its time discussing family life. It argued that the wife although above the children is below the husband and the father figure "is a king in his owne house", and was an important

William Gouge (1575–1653) was an English

William Gouge (1575–1653) was an English Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

clergyman and author. He was a minister and preacher at St Ann Blackfriars for 45 years, from 1608, and a member of the Westminster Assembly

The Westminster Assembly of Divines was a council of divines (theologians) and members of the English Parliament appointed from 1643 to 1653 to restructure the Church of England. Several Scots also attended, and the Assembly's work was adopt ...

from 1643.

Life

He was born inStratford-le-Bow

Bow () is an area of East London within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is primarily a built-up and mostly residential area and is east of Charing Cross.

It was in the Historic counties of England, traditional county of Middlesex but ...

, Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a historic county in southeast England. Its area is almost entirely within the wider urbanised area of London and mostly within the ceremonial county of Greater London, with small sections in neighbour ...

, and baptised on 6 November 1575. He was educated at Felsted, St. Paul's School, Eton College

Eton College () is a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. intended as a sister institution to King's College, ...

, and King's College, Cambridge

King's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Formally The King's College of Our Lady and Saint Nicholas in Cambridge, the college lies beside the River Cam and faces out onto King's Parade in the centre of the cit ...

. He graduated B.A. in 1598 and M.A. in 1601.Francis J. Bremer, Tom Webster, ''Puritans and Puritanism in Europe and America: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia'' (2006), p. 111.

Before moving to London, he was a Fellow and lecturer at Cambridge, where he caused a near-riot by his advocacy of Ramism

Ramism was a collection of theories on rhetoric, logic, and pedagogy based on the teachings of Petrus Ramus, a French academic, philosopher, and Huguenot convert, who was murdered during the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre in August 1572.

Accord ...

over the traditional methods of Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

. (This story about Gouge, who lectured on logic, is related in Wilbur Samuel Howell's ''Logic and Rhetoric in England 1500-1700'' (1956) as an account from Samuel Clarke

Samuel Clarke (11 October 1675 – 17 May 1729) was an English philosopher and Anglican cleric. He is considered the major British figure in philosophy between John Locke and George Berkeley.

Early life and studies

Clarke was born in Norwich, ...

, and is not reliably dated.)

At Blackfriars, he was initially assistant to Stephen Egerton (c.1554-1622), taking over as lecturer.

He proposed an early dispensational scheme. He took an interest in Sir Henry Finch's ''Calling of the Jews'', and published it under his own name; this led to a spell of imprisonment in 1621, since the publication displeased James I of England

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until ...

.''Concise Dictionary of National Biography''

Already nearly 70 years old, he attended the Westminster Assembly regularly, and was made chairman in 1644 of the committee set up to draft the Westminster Confession

The Westminster Confession of Faith is a Reformed confession of faith. Drawn up by the 1646 Westminster Assembly as part of the Westminster Standards to be a confession of the Church of England, it became and remains the " subordinate standard ...

. The other original members of the committee were John Arrowsmith, Cornelius Burges

Cornelius Burges or Burgess, DD (1589? – 1665), was an English minister. He was active in religious controversy prior to and around the time of the Commonwealth of England and The Protectorate, following the English Civil War. In the years f ...

, Jeremiah Burroughs, Thomas Gataker

Thomas Gataker (* London, 4 September 1574 – † Cambridge, 27 June 1654) was an English clergyman and theologian.

Life

He was born in London, the son of Thomas Gatacre. He was educated at St John's College, Cambridge. From 1601 to 1611 he h ...

, Thomas Goodwin

Thomas Goodwin (Rollesby, Norfolk, 5 October 160023 February 1680), known as "the Elder", was an English Puritan theologian and preacher, and an important leader of religious Independents. He served as chaplain to Oliver Cromwell, and was impos ...

, Joshua Hoyle

Joshua Hoyle (died 6 December 1654) was a Professor of Divinity at Trinity College, Dublin and Master of University College, Oxford during the Commonwealth of England.

Life

He was born at Sowerby, Yorkshire, and educated at Magdalen Hall, Oxfor ...

, Thomas Temple, and Richard Vines He was appointed as an Assessor on 26 November 1647. He was appointed prolocutor A prolocutor is a chairman of some ecclesiastical assemblies in Anglicanism.

Usage in the Church of England

In the Church of England, the Prolocutor is chair of the lower house of the Convocations of Canterbury and York, the House of Clergy. The P ...

of the Provincial Assembly of London on 3 May 1647.

''Of Domesticall Duties'' and the family

''Of Domesticall Duties'' (1622) was a popular and thorough text of its time discussing family life. It argued that the wife although above the children is below the husband and the father figure "is a king in his owne house", and was an important

''Of Domesticall Duties'' (1622) was a popular and thorough text of its time discussing family life. It argued that the wife although above the children is below the husband and the father figure "is a king in his owne house", and was an important conduct book

Conduct books or conduct literature is a genre of books that attempt to educate the reader on social norms and ideals. As a genre, they began in the mid-to-late Middle Ages, although antecedents such as ''The Maxims of Ptahhotep'' (c. 2350 BC) ...

of its period, running to later editions. He considered adultery

Adultery (from Latin ''adulterium'') is extramarital sex that is considered objectionable on social, religious, moral, or legal grounds. Although the sexual activities that constitute adultery vary, as well as the social, religious, and legal ...

equally bad in both genders, and encouraged love matches.

Gouge himself was father to 13 children. His wife Elizabeth, née Calton, died shortly after the birth of the last of them. They had married in the early 17th century, in effect by arrangement, when Gouge was put under pressure by his family. Elizabeth had been brought up by the wife of an Essex minister, John Huckle, and was eulogised after her death.

Other writings

According to Ann Thompson, ''The Whole Armor of God'' (1616) illustrates the shift from "transcendent faith" in William Perkins and Samuel Ward, to "immanent faith" in a succeeding generation of Puritan writers. In ''God's Three Arrows: Plague, Famine, Sword'' (1625 and 1631), he mentioned the idea thatplague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pe ...

finds victims in poorer people, because they are more easily spared. They should not be allowed to flee affected areas, and nor should magistrates and the aged; but others may properly do so. In common with other Protestant theologians of the time, he supported the idea of holy war

A religious war or a war of religion, sometimes also known as a holy war ( la, sanctum bellum), is a war which is primarily caused or justified by differences in religion. In the modern period, there are frequent debates over the extent to wh ...

.

His massive ''Commentary on the Whole Epistle to the Hebrews'' appeared in 1655 in three volumes, replete with detail and sermon outlines. It was seen into print by his eldest son, Thomas Gouge (c.1605-1681), It was reprinted by James Nichol of Edinburgh in 1866.

Works

* ''The Whole Armor of God'' (1616) * ''Of Domestical Duties'' (1622) * ''A Guide to Goe to God: or, an Explanation of the Perfect Patterne of Prayer, the Lords prayer.'' (1626) * ''The dignitie of chiualrie'' (1626) sermon to the Artillery Company of London * ''A Short Catechism'' (1635) * ''A Recovery from Apostacy'' (1639) * ''The Sabbath's Sanctification'' (1641) * ''The Saint's Support'' (1642) fast sermon in Parliament * ''The Progress of Divine Providence'' (1645) * ''Commentary on the Whole Epistle to the Hebrews'' (1655)Family

Five of his uncles were noted Puritans: Laurence Chaderton and William Whitaker married sisters of his mother, whileNathaniel

, nickname =

{{Plainlist,

* Nat

* Nate

, footnotes =

Nathaniel is an English variant of the biblical Greek name Nathanael.

People with the name Nathaniel

* Nathaniel Archibald (1952–2018), American basketball player

* Nat ...

, Samuel and Ezekiel Culverwell

Ezekiel (; he, יְחֶזְקֵאל ''Yəḥezqēʾl'' ; in the Septuagint written in grc-koi, Ἰεζεκιήλ ) is the central protagonist of the Book of Ezekiel in the Hebrew Bible.

In Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, Ezekiel is acknow ...

were her brothers. His cousin, Mary Culverwell, married Ezekiel Cheever.

Notes

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Gouge, William 1573 births 1653 deaths 17th-century English Anglican priests Westminster Divines People from Bow, London 16th-century English clergy People educated at Felsted School People educated at St Paul's School, London People educated at Eton College Alumni of King's College, Cambridge Clergy from London