William D. Leahy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Daniel Leahy () (May 6, 1875 – July 20, 1959) was an American naval officer who served as the most senior United States military officer on active duty during

William Daniel Leahy was born in

William Daniel Leahy was born in

The Philippine–American War was still ongoing, and the ''Castine'' supported American operations on Marinduque and

The Philippine–American War was still ongoing, and the ''Castine'' supported American operations on Marinduque and  On February 22, 1907, Leahy returned to Annapolis as instructor in the department of physics and chemistry. He also coached the academy rifle team. After two years ashore, he received orders on August 14, 1909, to return to San Francisco and sea duty as navigator of the

On February 22, 1907, Leahy returned to Annapolis as instructor in the department of physics and chemistry. He also coached the academy rifle team. After two years ashore, he received orders on August 14, 1909, to return to San Francisco and sea duty as navigator of the

As Leahy's three-year tour of shore duty approached its end in 1915, he hoped to command the new

As Leahy's three-year tour of shore duty approached its end in 1915, he hoped to command the new

Admiral Charles F. Hughes elected to retire rather than enforce the cuts, and he was replaced by Pratt. Pratt and Leahy soon clashed over cuts to shipbuilding, and Pratt attempted to have Leahy reassigned as chief of staff of the Pacific Fleet. Leahy had the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation block this, but decided that it would be in his best interest to get away from Pratt, and he secured command of the destroyers of the

Admiral Charles F. Hughes elected to retire rather than enforce the cuts, and he was replaced by Pratt. Pratt and Leahy soon clashed over cuts to shipbuilding, and Pratt attempted to have Leahy reassigned as chief of staff of the Pacific Fleet. Leahy had the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation block this, but decided that it would be in his best interest to get away from Pratt, and he secured command of the destroyers of the

From September 1939 to November 1940, Leahy served as Governor of Puerto Rico after Roosevelt removed

From September 1939 to November 1940, Leahy served as Governor of Puerto Rico after Roosevelt removed  Leahy oversaw the development of military bases and stations across the island. At the time of his appointment as governor, the only naval installations were a radio station and a hydrographic office. On October 30, 1939, a fixed fee contract was awarded for construction of the Naval Air Station Isla Grande. Subsequently the scope of activity was widened to include the

Leahy oversaw the development of military bases and stations across the island. At the time of his appointment as governor, the only naval installations were a radio station and a hydrographic office. On October 30, 1939, a fixed fee contract was awarded for construction of the Naval Air Station Isla Grande. Subsequently the scope of activity was widened to include the

Leahy attended his first meeting of the

Leahy attended his first meeting of the

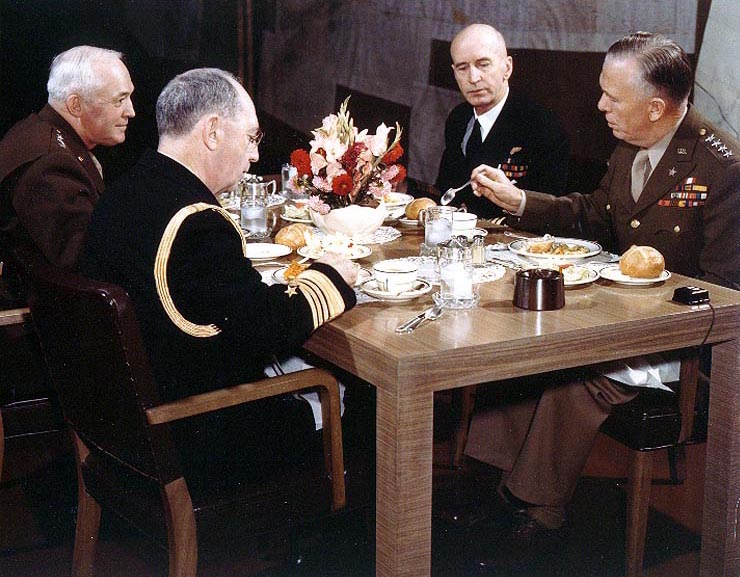

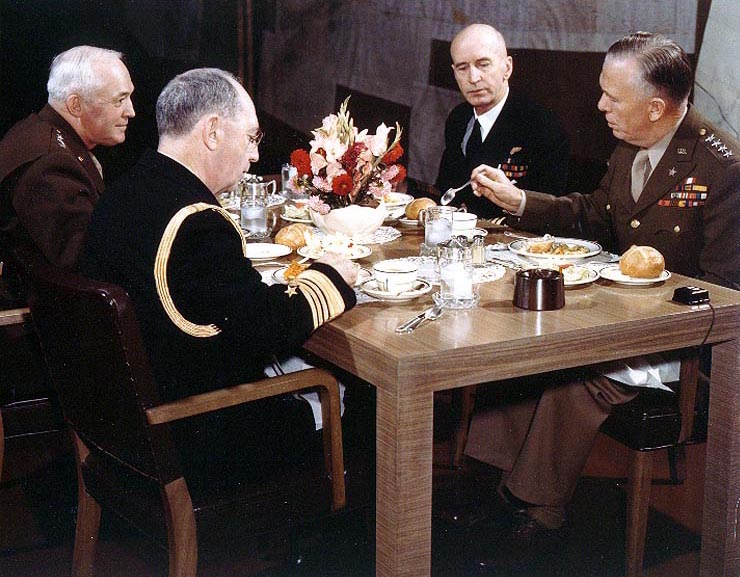

On November 12, 1943, Roosevelt, Hopkins, Leahy, King and Marshall set off together from Hampton Roads on the battleship . Roosevelt occupied the captain's cabin, and Leahy the one for an embarked admiral; Marshall, the next most senior officer, had the chief of staff's cabin. The President had his own mess, where he dined with Hopkins, Leahy, McIntire, and Roosevelt's aides, Rear Admiral Wilson Brown and Major General Edwin "Pa" Watson; the other senior officers took their meals with the ships' officers. They reached Mers-el-Kebir on November 20, from whence they flew to

On November 12, 1943, Roosevelt, Hopkins, Leahy, King and Marshall set off together from Hampton Roads on the battleship . Roosevelt occupied the captain's cabin, and Leahy the one for an embarked admiral; Marshall, the next most senior officer, had the chief of staff's cabin. The President had his own mess, where he dined with Hopkins, Leahy, McIntire, and Roosevelt's aides, Rear Admiral Wilson Brown and Major General Edwin "Pa" Watson; the other senior officers took their meals with the ships' officers. They reached Mers-el-Kebir on November 20, from whence they flew to  Roosevelt, Leahy and presidential speech writer

Roosevelt, Leahy and presidential speech writer

On January 24, 1946, Leahy was appointed to the interim National Intelligence Authority (NIA), which oversaw activities of the nascent Central Intelligence Group. The following year the National Security Act of 1947 replaced these organizations with the National Security Council and the

On January 24, 1946, Leahy was appointed to the interim National Intelligence Authority (NIA), which oversaw activities of the nascent Central Intelligence Group. The following year the National Security Act of 1947 replaced these organizations with the National Security Council and the

Leahy died at the U.S. Naval Hospital in

Leahy died at the U.S. Naval Hospital in

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. He held multiple titles and was at the center of all major military decisions of the U.S. during World War II. As fleet admiral, Leahy was the first U.S. naval officer ever to hold a five-star rank

A five-star rank is the highest military rank in many countries.Oxford English Dictionary (OED), 2nd Edition, 1989. "five" ... "five-star adj., ... (b) U.S., applied to a general or admiral whose badge of rank includes five stars;" The rank is t ...

in the U.S. Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. The armed forces consists of six service branches: the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and Coast Guard. The president of the United States is the ...

. He has been described by historian Phillips O'Brien as the "second most powerful man in the world" for his influence over U.S. foreign and military policy throughout the war.

An 1897 graduate of the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

at Annapolis, Maryland, Leahy saw service in the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cloc ...

, the Philippine–American War, Boxer Rebellion in China, the Banana Wars

The Banana Wars were a series of conflicts that consisted of military occupation, police action, and intervention by the United States in Central America and the Caribbean between the end of the Spanish–American War in 1898 and the inceptio ...

and World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. As Chief of Naval Operations from 1937 to 1939, he was the senior officer in the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

, overseeing the preparations for war. After retiring from the Navy, he was appointed in 1939 by his close friend President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

as the governor of Puerto Rico. In his most controversial role, he served as the U.S. Ambassador to France

The United States ambassador to France is the official representative of the president of the United States to the president of France. The United States has maintained diplomatic relations with France since the American Revolution. Relations we ...

from 1940 to 1942, but had limited success in keeping the Vichy government

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its terr ...

free of German control.

Leahy was recalled to active duty as the personal Chief of Staff to President Roosevelt in 1942 and served in that position through the rest of World War II. He was the first ''de facto'' Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and presided over the American delegation to the Combined Chiefs of Staff of the U.S. and Great Britain. Leahy was a major decision-maker during the war and was second only to the President in authority and influence. He served Roosevelt's successor Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

, helping shape U.S. postwar foreign policy until finally retiring in 1949. From 1942 until his retirement, Leahy was the highest-ranking active-duty member of the U.S. military, reporting only to the President.

Early life and education

William Daniel Leahy was born in

William Daniel Leahy was born in Hampton, Iowa

Hampton is a town in Franklin County, Iowa, United States. The population was 4,337 at the time of the 2020 census. It is the county seat of Franklin County.

Geography

Hampton's longitude and latitude coordinates, in decimal form are 42.74316 ...

, on May 6, 1875, the first of eight children of Michael Arthur Leahy, a lawyer and American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

veteran who was elected to the Wisconsin Legislature

The Wisconsin Legislature is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Wisconsin. The Legislature is a bicameral body composed of the upper house, Wisconsin State Senate, and the lower Wisconsin State Assembly, both of which have had Republica ...

in 1872, and his wife Rose Mary Hamilton. He had five younger brothers and a sister. Both his parents were born in the United States but his grandparents were immigrants from Ireland, his paternal grandparents having arrived in the United States in 1836. In 1882, the family moved to Ashland, Wisconsin, where Leahy attended high school. His nose was broken in an American football

American football (referred to simply as football in the United States and Canada), also known as gridiron, is a team sport played by two teams of eleven players on a rectangular field with goalposts at each end. The offense, the team wi ...

game and his family lacked the money to get it fixed, so it remained crooked for the rest of his life.

Leahy wanted to attend the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

at West Point, New York

West Point is the oldest continuously occupied military post in the United States. Located on the Hudson River in New York, West Point was identified by General George Washington as the most important strategic position in America during the Ame ...

, but this required an appointment from his local Congressman, Thomas Lynch. Lynch had no appointments to West Point to offer, but he offered Leahy an appointment to the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

in Annapolis, Maryland, which was much less popular among boys in the Midwestern United States

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of the United States. I ...

. Leahy passed the entrance examinations and was admitted as a naval cadet

Officer Cadet is a rank held by military cadets during their training to become commissioned officers. In the United Kingdom, the rank is also used by members of University Royal Naval Units, University Officer Training Corps and University A ...

in May 1893.

Leahy learned how to sail on a sailing ship, the on a summer cruise to Europe, although the vessel only made it as far as the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

before breaking down. He graduated 35th out of 47 in the class of 1897. His class was the most successful ever: five of its members would reach four-star rank

A four-star rank is the rank of any four-star officer described by the NATO OF-9 code. Four-star officers are often the most senior commanders in the armed services, having ranks such as (full) admiral, (full) general, colonel general, army ge ...

while on active duty: Leahy, Thomas C. Hart

Thomas Charles Hart (June 12, 1877July 4, 1971) was an admiral in the United States Navy, whose service extended from the Spanish–American War through World War II. Following his retirement from the navy, he served briefly as a United States Se ...

, Arthur J. Hepburn, Orin G. Murfin and Harry E. Yarnell. , no other class had had more than four.

Naval service

Spanish-American War

Until 1912 naval cadets graduating from Annapolis had to complete two years' duty at sea and pass examinations before they could be commissioned asensign

An ensign is the national flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality. The ensign is the largest flag, generally flown at the stern (rear) of the ship while in port. The naval ensign (also known as war ensign), used on warships, may be diffe ...

s. Leahy was assigned to the battleship , which was then at Vancouver, British Columbia

Vancouver ( ) is a major city in western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the city, up from 631,486 in 2016. The ...

for celebrations of Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

's Diamond Jubilee

A diamond jubilee celebrates the 60th anniversary of a significant event related to a person (e.g. accession to the throne or wedding, among others) or the 60th anniversary of an institution's founding. The term is also used for 75th anniver ...

. He was on board when she made a dash through the Strait of Magellan, and around South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sout ...

in the spring of 1898 to participate in the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cloc ...

. The ''Oregon'' took part in the blockade and bombardment of Santiago

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile as well as one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is the center of Chile's most densely populated region, the Santiago Metropolitan Region, whos ...

and shelled the small town of Guantánamo

Guantánamo (, , ) is a municipality and city in southeast Cuba and capital of Guantánamo Province.

Guantánamo is served by the Caimanera port near the site of a U.S. naval base. The area produces sugarcane and cotton wool. These are traditi ...

, which Leahy felt was "unnecessary and cruel". In the Battle of Santiago on July 3, Leahy was in command of the ship's forward turret. This was the only naval battle Leahy witnessed in person.

Seeking further action, Leahy volunteered to serve on the gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-ste ...

, which was bound for the war in the Pacific, traveling via the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

and the Suez Canal, but he got only as far as Ceylon when he received orders to report to Annapolis for his final ensign's examinations. He was therefore left behind, and had to return to the United States on the . He reached Annapolis in June 1899. He passed his examinations, and was commissioned as an ensign on July 1, 1899. After few weeks' leave, spent with his parents in Wisconsin, and a few months service on the cruiser at the Mare Island Navy Yard

The Mare Island Naval Shipyard (MINSY) was the first United States Navy base established on the Pacific Ocean. It is located northeast of San Francisco in Vallejo, California. The Napa River goes through the Mare Island Strait and separates t ...

, he joined the monitor

Monitor or monitor may refer to:

Places

* Monitor, Alberta

* Monitor, Indiana, town in the United States

* Monitor, Kentucky

* Monitor, Oregon, unincorporated community in the United States

* Monitor, Washington

* Monitor, Logan County, West ...

on October 12, 1899. A week later it set sail for the Philippines. It arrived in Manila on November 24, and Leahy rejoined the crew of the ''Castine'' five days later.

China and Philippine–American Wars

On December 17, 1899, ''Castine'' sailed forNagasaki

is the capital and the largest Cities of Japan, city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole Nanban trade, port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hi ...

, but it developed engine trouble on February 12 and stopped in Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flowin ...

to make repairs. While it was there the Boxer Rebellion broke out in China, and it was retained in Shanghai to help British, French and Japanese forces guard the city, although Leahy did not like their chances if the 4,500 Chinese troops in the vicinity joined the uprising, as they had in the Battle of Tientsin

The Battle of Tientsin, or the Relief of Tientsin, occurred on 13–14 July 1900, during the Boxer Rebellion in Northern China. A multinational military force, representing the Eight-Nation Alliance, rescued a besieged population of foreign nat ...

. On August 28, the ''Castine'' was ordered to Amoy

Xiamen ( , ; ), also known as Amoy (, from Hokkien pronunciation ), is a sub-provincial city in southeastern Fujian, People's Republic of China, beside the Taiwan Strait. It is divided into six districts: Huli, Siming, Jimei, Tong' ...

help protect American interests there against the possibility of a Japanese coup. The ''Castine'' returned to the Philippines, arriving back in Manila on September 16, 1900.

The Philippine–American War was still ongoing, and the ''Castine'' supported American operations on Marinduque and

The Philippine–American War was still ongoing, and the ''Castine'' supported American operations on Marinduque and Iloilo

Iloilo (), officially the Province of Iloilo ( hil, Kapuoran sang Iloilo; krj, Kapuoran kang Iloilo; tl, Lalawigan ng Iloilo), is a province in the Philippines located in the Western Visayas region. Its capital is the City of Iloilo, the ...

. Unlike most Americans, Leahy was appalled by American brutality and the widespread use of torture. Still an ensign, he was given his first command, the gunboat , a refitted ex-Spanish vessel. It had a crew of 23. His period in command ended when the ''Mariveles'' lost one of its propellers, and had to be laid up for repairs. He was then reassigned to the , a stores ship

Store may refer to:

Enterprises

* Retail store, a shop where merchandise is sold, usually products and usually on a retail basis, and where wares are often kept

** App store, an online retail store where apps are sold, included in many mobile op ...

which was engaged in bringing supplies from Australia to the Philippines. While in the Philippines he passed the examinations required for promotion to lieutenant, junior grade, was promoted to that rank on July 1, 1902. He made his final trip to the Philippines in September 1902,and returned to the United States later that year.

Sea duty alternated with duty ashore. Leahy was assigned to the training ship in San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17th ...

, where he was promoted to lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

on December 31, 1903. He met and courted Louise Tennent Harrington, whose older sister Mary was engaged to Albert P. Niblack, an officer of the Annapolis class of 1880 under whom Leahy had served. Leahy married Louise on February 3, 1904. Louise subsequently convinced him to convert from Roman Catholicism and become an Episcopalian.

Leahy helped commission the cruiser but swapped assignments with an officer on the so that he could remain in San Francisco with Louise, who was pregnant. Over the next two years the ''Boston'' cruised back and forth between San Francisco and Panama, where the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a condui ...

was under construction. He was in Acapulco when their son and only child, William Harrington Leahy, was born on October 27, 1904, and did not see his son until five months later. However, he was present for the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. His family had to leave their house in the face of the resulting fires. It survived undamaged, although they had to live in a hotel for several months before they could return.

On February 22, 1907, Leahy returned to Annapolis as instructor in the department of physics and chemistry. He also coached the academy rifle team. After two years ashore, he received orders on August 14, 1909, to return to San Francisco and sea duty as navigator of the

On February 22, 1907, Leahy returned to Annapolis as instructor in the department of physics and chemistry. He also coached the academy rifle team. After two years ashore, he received orders on August 14, 1909, to return to San Francisco and sea duty as navigator of the armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast eno ...

, commanded by Captain Henry T. Mayo, in whom Leahy found a patron and a role model. In September, the ''California'' was one of eight ships that paid an official visit to Japan, where Leahy saw Admiral Heihachirō Tōgō

Heihachirō (written: 平八郎) is a masculine Japanese given name. Notable people with the name include:

*, Japanese photographer

*, Japanese samurai

*, Imperial Japanese Navy admiral

{{DEFAULTSORT:Heihachiro

Japanese masculine given names

Mas ...

. Mayo switched Leahy's assignment from navigator to gunnery officer, a change Leahy came to see as a wise one.

Leahy was promoted to lieutenant commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding ran ...

on September 15, 1909, and in January 1911, the commander-in-chief of the Pacific Fleet, Rear Admiral Chauncey Thomas Jr., chose him as his fleet gunnery officer. In October, the ''California'' returned to San Francisco for a fleet review in honor of President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

, and Leahy served as Taft's temporary naval aide for four days.

Banana Wars

Rear Admiral William H. H. Southerland succeeded Thomas as commander of the Pacific Fleet on April 21, 1912. The ''California'' sailed to Manila and then to Japan before returning to San Francisco on August 15. A few weeks later, Southerland received orders to proceed to Nicaragua and be prepared to deploy a landing force for theUnited States occupation of Nicaragua

The United States occupation of Nicaragua from 1912 to 1933 was part of the Banana Wars, when the US military invaded various Latin American countries from 1898 to 1934. The formal occupation began in 1912, even though there were various othe ...

. In addition to his duties as gunnery officer, Leahy became the chief of staff of the expeditionary force and the commander of the small garrison at Corinto, Nicaragua

Corinto is a town, with a population of 18,552 (2021 estimate), on the northwest Pacific coast of Nicaragua in the province of Chinandega. The municipality was founded in 1863.

History Early years

The town of Corinto was founded in 1849. It first ...

. He came under fire while repeatedly escorting reinforcements and supplies over the railroad line to León. Privately, he thought that the United States was backing the wrong side, propping up a conservative elite who were exploiting the Nicaraguan people.

In October 1912, Leahy came ashore in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, as assistant director of gunnery exercises and engineering competitions. Then, in 1913, Mayo had him assigned to the Bureau of Navigation

The Bureau of Navigation, later the Bureau of Navigation and Steamboat Inspection and finally the Bureau of Marine Inspection and Navigation — not to be confused with the United States Navys Bureau of Navigation — was an agency of the United ...

as a detail officer. Mayo and then his replacement, Rear Admiral William Fullam, was reassigned, leaving Leahy in charge of one of the Navy's most sensitive offices. In this role he was in charge of all officer assignments. He also established a close friendship with the Assistant Secretary of the Navy

Assistant Secretary of the Navy (ASN) is the title given to certain civilian senior officials in the United States Department of the Navy.

From 1861 to 1954, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy was the second-highest civilian office in the Depar ...

, Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

. Leahy's wife Louise enjoyed the social milieu of Washington, and socialized with Addie Daniels, the wife of Josephus Daniels, the Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

.

As Leahy's three-year tour of shore duty approached its end in 1915, he hoped to command the new

As Leahy's three-year tour of shore duty approached its end in 1915, he hoped to command the new destroyer tender

A destroyer tender or destroyer depot ship is a type of depot ship: an auxiliary ship designed to provide maintenance support to a flotilla of destroyers or other small warships. The use of this class has faded from its peak in the first half of ...

but Daniels had the assignment changed to command of the Secretary of the Navy's dispatch gunboat, the . Leahy assumed command of the ''Dolphin'' on September 18, 1915. The ship took part in the United States occupation of Haiti

The United States occupation of Haiti began on July 28, 1915, when 330 U.S. Marines landed at Port-au-Prince, Haiti, after the National City Bank of New York convinced the President of the United States, Woodrow Wilson, to take control of ...

, where Leahy again acted as chief of staff, this time to Rear Admiral William B. Caperton. In May 1916, ''Dolphin'' participated in the United States occupation of the Dominican Republic. During the summer, Roosevelt used it as his family yacht, cruising down the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between N ...

from the Roosevelt family estate in Hyde Park, New York

Hyde Park is a town in Dutchess County, New York, United States, bordering the Hudson River north of Poughkeepsie. Within the town are the hamlets of Hyde Park, East Park, Staatsburg, and Haviland. Hyde Park is known as the hometown of Fran ...

, and along the coast to his holiday house on Campobello Island

Campobello Island (, also ) is the largest and only inhabited island in Campobello, a civil parish in southwestern New Brunswick, Canada, near the border with Maine, United States. The island's permanent population in 2021 was 949. It is the s ...

. Leahy was promoted to commander on August 29, 1916.

World War I

Following the United States entry intoWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

In April 1917, ''Dolphin'' was sent to the United States Virgin Islands

The United States Virgin Islands,. Also called the ''American Virgin Islands'' and the ''U.S. Virgin Islands''. officially the Virgin Islands of the United States, are a group of Caribbean islands and an unincorporated and organized territory ...

to assert America's control there. There was a rumor that a Danish-flagged freighter in the vicinity, the ''Nordskov'', was a German merchant raider

Merchant raiders are armed commerce raiding ships that disguise themselves as non-combatant merchant vessels.

History

Germany used several merchant raiders early in World War I (1914–1918), and again early in World War II (1939–1945). The cap ...

in disguise, and ''Dolphin'' was sent to investigate. If it had been, Leahy would have been outgunned, but an inspection determined that the rumors were false. In July 1917, Leahy became the executive officer of . It was the Navy's newest battleship, but it was not sent to Europe due to teething troubles with what was then a radical new design and a shortage of fuel oil in Britain.

In April 1918 Leahy assumed command of a troop transport

A troopship (also troop ship or troop transport or trooper) is a ship used to carry soldiers, either in peacetime or wartime. Troopships were often drafted from commercial shipping fleets, and were unable land troops directly on shore, typicall ...

the . Shortly before it was due to depart for France, Leahy was summoned to Washington, D.C., by the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), Admiral William S. Benson

William Shepherd Benson (25 September 1855 – 20 May 1932) was an admiral in the United States Navy and the first chief of naval operations (CNO), holding the post throughout World War I.

Early life and career

Born in Bibb County, Georgi ...

, who offered him the position of the Navy's director of gunnery. Leahy told him that he wanted to remain on the ''Princess Matoika''. A compromise was reached; Leahy was permitted to cross the Atlantic once before becoming director of gunnery. Traveling in convoy, the ''Princess Matoika'' reached Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

* Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

* Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

** Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Br ...

on May 23, 1918, and disembarked its troops. Leahy was awarded the Navy Cross

The Navy Cross is the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps' second-highest military decoration awarded for sailors and marines who distinguish themselves for extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force. The medal is eq ...

"for distinguished service in the line of his profession as Commanding Officer of the USS ''Princess Matoika'', engaged in the important, exacting and hazardous duty of transporting and escorting troops and supplies to European ports through waters infested with enemy submarines and mines during World War I."

Leahy, who was promoted to captain on July 1, 1918, was soon on his way back to Europe, to confer with representatives of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

and discuss their gunnery practices. He reached London later that month, where he reported to the U.S. Navy commander in Europe, Vice Admiral William S. Sims, who had been a critic of the U.S. Navy's gunnery in the Spanish-American War. Leahy met with his British counterpart, Captain Frederic Dreyer

Admiral Sir Frederic Charles Dreyer, (8 January 1878 – 11 December 1956) was an officer of the Royal Navy. A gunnery expert, he developed a fire control system for British warships, and served as flag captain to Admiral Sir John Jellicoe at ...

, and the chief gunnery officer of the Anglo-American Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the F ...

, Captain Ernle Chatfield

Admiral of the Fleet Alfred Ernle Montacute Chatfield, 1st Baron Chatfield, (27 September 1873 – 15 November 1967) was a Royal Navy officer. During the First World War he was present as Sir David Beatty's Flag-Captain at the Battle of ...

. Leahy was attached to the staff of Rear Admiral Hugh Rodman, the commander of the American division of the Grand Fleet, and was able to view a gunnery exercise from the British battleship . On the way home he visited Paris, where he was appalled at the German use of a long-range gun to bombard the city, which he considered an indiscriminate targeting of civilians and militarily useless. He embarked for home on the at Brest on August 12, 1918.

Sea duty between the wars

In February 1921, Leahy sailed for Europe, where he assumed command of the cruiser on April 2. In May he was ordered to take command the cruiser , the flagship of the naval detachment in Turkish waters during the Greco-Turkish War. He was able to spend a couple of weeks in the French countryside with Louise, who spoke fluent French, before taking theOrient Express

The ''Orient Express'' was a long-distance passenger train service created in 1883 by the Belgian company ''Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits'' (CIWL) that operated until 2009. The train traveled the length of continental Europe and int ...

to Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya ( Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

, where he reported to the American commander there, Rear Admiral Mark L. Bristol

Mark Lambert Bristol (April 17, 1868 – May 13, 1939) was a rear admiral in the United States Navy.

Biography

He was born on April 17, 1868, in Glassboro, New Jersey. Bristol graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1887. During the Spa ...

, on May 30. Leahy had the role of safeguarding American interests in Turkey. He had to play the diplomat, attending parties and receptions, and organizing American events. He reveled in this assignment.

The next step in a successful naval career would normally have been to attend the Naval War College

The Naval War College (NWC or NAVWARCOL) is the staff college and "Home of Thought" for the United States Navy at Naval Station Newport in Newport, Rhode Island. The NWC educates and develops leaders, supports defining the future Navy and associ ...

. Leahy submitted repeated requests but was never sent. At the end of 1921, he was given command of the minelayer

A minelayer is any warship, submarine or military aircraft deploying explosive mines. Since World War I the term "minelayer" refers specifically to a naval ship used for deploying naval mines. "Mine planting" was the term for installing control ...

and concurrent command of Mine Squadron One. He then returned to Washington, D.C., where he served as director of Officer Personnel in the Bureau of Navigation from 1923 to 1926. After three years of shore duty, he was given command of the battleship . In biennial competitions in gunnery, engineering and battle efficiency, the ''New Mexico'' won all three in 1927–1928.

Flag officer

On October 14, 1927, he reachedflag rank

A flag officer is a commissioned officer in a nation's armed forces senior enough to be entitled to fly a flag to mark the position from which the officer exercises command.

The term is used differently in different countries:

*In many countries ...

, the first member of his cadet class to do so, and returned to Washington as the Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance The Bureau of Ordnance (BuOrd) was a United States Navy organization, which was responsible for the procurement, storage, and deployment of all naval weapons, between the years 1862 and 1959.

History

Congress established the Bureau in the Departme ...

. The following year he bought a town house on Florida Avenue

Florida Avenue is a major street in Washington, D.C. It was originally named Boundary Street, because it formed the northern boundary of the Federal City under the 1791 L'Enfant Plan. With the growth of the city beyond its original borders, Bound ...

near Dupont Circle

Dupont Circle (or DuPont Circle) is a traffic circle, park, neighborhood and historic district in Northwest Washington, D.C. The Dupont Circle neighborhood is bounded approximately by 16th Street NW to the east, 22nd Street NW t ...

for $20,000 (). He also had assets that he had acquired through his marriage to Louise: stocks in the Colusa County Bank and agricultural land in the Sacramento Valley in California. But in the wake of the Wall Street Crash of 1929

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Great Crash, was a major American stock market crash that occurred in the autumn of 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange coll ...

, President Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

determined to effect cuts in the Navy's budget, and his representative, Rear Admiral William V. Pratt

William Veazie Pratt (28 February 1869 – 25 November 1957) was an admiral in the United States Navy. He served as the President of the Naval War College from 1925 to 1927, and as the 5th Chief of Naval Operations from 1930 to 1933.

Early l ...

, negotiated the London Naval Treaty that limited naval construction. The list of canceled ships included two aircraft carriers, three cruisers, a destroyer and six submarines. Leahy was in charge of implementing these cuts, and he was appalled at the human toll; some 5,000 workers lost their jobs, many of them highly skilled shipyard workers who faced long-term unemployment during the Great Depression.

Admiral Charles F. Hughes elected to retire rather than enforce the cuts, and he was replaced by Pratt. Pratt and Leahy soon clashed over cuts to shipbuilding, and Pratt attempted to have Leahy reassigned as chief of staff of the Pacific Fleet. Leahy had the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation block this, but decided that it would be in his best interest to get away from Pratt, and he secured command of the destroyers of the

Admiral Charles F. Hughes elected to retire rather than enforce the cuts, and he was replaced by Pratt. Pratt and Leahy soon clashed over cuts to shipbuilding, and Pratt attempted to have Leahy reassigned as chief of staff of the Pacific Fleet. Leahy had the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation block this, but decided that it would be in his best interest to get away from Pratt, and he secured command of the destroyers of the Scouting Force

The Scouting Fleet was created in 1922 as part of a major, post-World War I reorganization of the United States Navy. The Atlantic and Pacific fleets, which comprised a significant portion of the ships in the United States Navy, were combined into ...

on the West Coast. Leahy's dislike of Hoover was intensified by his dire personal circumstances. He could not find a tenant for the Florida Avenue property at a rent that would pay for its upkeep; the price of food had fallen so much that his land in the Sacramento Valley could not generate a profit, and was seized by the government to recover unpaid taxes; and a run in January 1933 caused the Colusa County Bank to close its doors, taking with it Leahy's life savings, and leaving him with a large debt that he would not pay off until 1941.

Leahy's old friend Franklin Roosevelt was inaugurated as president on March 2, 1933, and he nominated Leahy as the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation. On May 6, 1933, Leahy and Louise boarded a train back to Washington, D.C.. As bureau chief, Leahy handled personnel matters with care and consideration. When his successor as the Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance, Rear Admiral Edgar B. Larimer, suffered a mental breakdown and was hospitalized, Leahy ensured that he was kept on the active list until he reached retirement age, thereby safeguarding his pension. When two midshipmen at Annapolis, John Hyland and Victor Krulak

Victor Harold Krulak (January 7, 1913 – December 29, 2008) was a decorated United States Marine Corps officer who saw action in World War II, Korea and Vietnam. Krulak, considered a visionary by fellow Marines, was the author of ''First to Figh ...

, faced expulsion for failing to reach the required minimum height of , Leahy waived the regulations to permit them to graduate with the class of 1934, and both went on to have distinguished careers.

Leahy formed a good working relationship with the new Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Henry L. Roosevelt, an Annapolis graduate and distant cousin of the President whom Leahy considered a close personal friend, but he clashed with the new CNO, Admiral William H. Standley, who sought to assert the power of the CNO over the bureau chiefs. In this he was opposed by Leahy and the Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics

The Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer) was the U.S. Navy's material-support organization for naval aviation from 1921 to 1959. The bureau had "cognizance" (''i.e.'', responsibility) for the design, procurement, and support of naval aircraft and relate ...

, Rear Admiral Ernest J. King

Ernest Joseph King (23 November 1878 – 25 June 1956) was an American naval officer who served as Commander in Chief, United States Fleet (COMINCH) and Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) during World War II. As COMINCH-CNO, he directed the Un ...

, who enlisted the aid of Henry Roosevelt and the Secretary of the Navy, Claude A. Swanson, to block it. In 1936, the commander-in-chief United States Fleet

The United States Fleet was an organization in the United States Navy from 1922 until after World War II. The acronym CINCUS, pronounced "sink us", was used for Commander in Chief, United States Fleet. This was replaced by COMINCH in December 1941 ...

(CINCUS), Admiral Joseph M. Reeves recommended Leahy for the position of Commander Battleships Battle Force, with the rank of vice admiral. Standley was opposed to this, but was unable to persuade Swanson or the President, who invited Leahy to a private chat at the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

before proceeding to take up his new posting.

Leahy assumed his new command on July 13, 1935. In October Roosevelt came out to California for the California Pacific International Exposition

The California Pacific International Exposition was an exposition held in San Diego, California during May 29, 1935–November 11, 1935 and February 12, 1936–September 9, 1936. The exposition was held in Balboa Park, San Diego's large c ...

. Leahy treated him to the largest fleet maneuver the U.S. Navy had ever carried out, with 129 warships, including 12 battleships, participating, which the President observed from the deck of the cruiser . On March 30, 1936, Leahy was promoted to the temporary rank of admiral and hoisted his four-star flag on the battleship as Commander Battle Force. One of his last acts in this post was a symbolic one: he transferred his flag to the aircraft carrier as a sign of his conviction that aircraft were now an integral part of sea power.

Chief of Naval Operations

In December 1935, Swanson told Leahy in confidence that he would be appointed the next CNO if Roosevelt won the 1936 presidential election. Roosevelt won the election with a landslide victory, and on November 10, 1936, it was announced that he would succeed Standley as CNO on January 1, 1937. As CNO, Leahy was content to let the bureau chiefs function as they always had, with the CNO acting as a '' primus inter pares''. On the other hand, Swanson was chronically ill, and Henry Roosevelt died on February 22, 1936.Charles Edison

Charles Edison (August 3, 1890 – July 31, 1969) was an American politician, businessman, inventor and animal behaviorist. He was the Assistant and then United States Secretary of the Navy, and served as the 42nd governor of New Jersey. Commonly ...

became the new assistant secretary, but he lacked experience in naval affairs.

Leahy began representing the Navy in cabinet meetings. He met with the President frequently; during his tenure as CNO, Roosevelt had 52 meetings with him, compared with 12 with his Army counterpart, General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

Malin Craig

Malin Craig (August 5, 1875 – July 25, 1945) was a general in the United States Army who served as the 14th Chief of Staff of the United States Army from 1935 to 1939. He served in World War I and was recalled to active duty during World War II ...

, none of which were private lunches. Moreover, meetings between Leahy and Roosevelt were sometimes on matters unrelated to the Navy, and frequently went on for hours. At one private lunch on April 15, 1937, Leahy and Roosevelt debated whether new battleships should have 16-inch or (cheaper) 14-inch guns. Leahy ultimately persuaded the President that the new s should have 16-inch guns. On May 22, Leahy accompanied the President and dignitaries including John Nance Garner, Harry Hopkins, James F. Byrnes

James Francis Byrnes ( ; May 2, 1882 – April 9, 1972) was an American judge and politician from South Carolina. A member of the Democratic Party, he served in U.S. Congress and on the U.S. Supreme Court, as well as in the executive branch, ...

, Morris Sheppard

John Morris Sheppard (May 28, 1875April 9, 1941) was a Democratic United States Congressman and United States Senator from Texas. He authored the Eighteenth Amendment (Prohibition) and introduced it in the Senate, and is referred to as "the fa ...

, Edwin C. Johnson, Claude Pepper

Claude Denson Pepper (September 8, 1900 – May 30, 1989) was an American politician of the Democratic Party, and a spokesman for left-liberalism and the elderly. He represented Florida in the United States Senate from 1936 to 1951, and the Mi ...

and Sam Rayburn on a cruise on the presidential yacht to watch a baseball game between congressmen and the press.

The most important issue confronting the administration was how to respond to the Japanese invasion of China

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

. The commander-in-chief of the Asiatic Fleet, Admiral Harry Yarnell, asked for four additional cruisers to help evacuate American citizens from the Shanghai International Settlement

The Shanghai International Settlement () originated from the merger in the year 1863 of the British and American enclaves in Shanghai, in which British subjects and American citizens would enjoy extraterritoriality and consular jurisdictio ...

, but the Secretary of State, Cordell Hull, thought this would be too provocative. Leahy went to Hyde Park to take the matter up with Roosevelt. The request was turned down: American isolationist sentiment was too strong to countenance the risk of being drawn into the conflict; Yarnell could use merchant ships, if he could find them. Leahy accepted this presidential decision, as he always did, even when he strongly disagreed. Leahy wrote in his diary that a Japanese threat to bomb the civilian population in China was "evidence, and a conclusive one, that the old accepted rules of warfare are no longer in effect."

On December 12, Leahy was informed of the USS ''Panay'' incident, in which an American gunboat on the Yangtze River

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest list of rivers of Asia, river in Asia, the list of rivers by length, third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in th ...

had been sunk by Japanese aircraft. He met with Hull to craft a response, and discussed the matter with Roosevelt on December 14. Leahy saw the ''Panay'' incident as a test of American resolve. He wanted to answer it with a show of force, with economic sanctions and a naval blockade of Japan. But among Roosevelt's advisors, he was the only one willing to countenance such a drastic step. Roosevelt agreed with him, but in an election year he felt he could not afford to antagonize the pacifists and isolationists. The Japanese apology therefore was accepted.

The ''Panay'' incident did prompt Roosevelt and Leahy to press ahead with plans for an ambitious shipbuilding program. On January 5, Roosevelt, Leahy and Edison met with Congressman Carl Vinson

Carl Vinson (November 18, 1883 – June 1, 1981) was an American politician who served in the U.S. House of Representatives for over 50 years and was influential in the 20th century expansion of the U.S. Navy. He was a member of the Democratic ...

to draw up a strategy for obtaining Congressional approval for a 20 percent increase in all classes of warships. The resulting Second Vinson Act

The Naval Act of 1938, known as the Second Vinson Act, was United States legislation enacted on May 17, 1938, that "mandated a 20% increase in strength of the United States Navy".displacement

Displacement may refer to:

Physical sciences

Mathematics and Physics

* Displacement (geometry), is the difference between the final and initial position of a point trajectory (for instance, the center of mass of a moving object). The actual path ...

of and destroyers with a total displacement of . Leahy had not thought it worthwhile to build more aircraft carriers, but five were added to what became the Two-Ocean Navy Act

The Two-Ocean Navy Act, also known as the Vinson-Walsh Act, was a United States law enacted on July 19, 1940, and named for Carl Vinson and David I. Walsh, who chaired the Naval Affairs Committee in the House and Senate respectively. The largest ...

, together with five s. Leahy also pushed for the construction of 24 oilers, which would be needed to project American sea power across the vastness of the Pacific. Before retiring as CNO, Leahy joined his wife Louise when she sponsored the first of these, the , which was commissioned on March 20, 1939.

Roosevelt threw a surprise party for Leahy on July 28, 1939, during which he presented him with the Navy Distinguished Service Medal. According to Leahy, Roosevelt said: "Bill, if we have a war, you're going to be right back here helping me run it." To make this easier, Vinson and David I. Walsh were asked to expedite legislation to keep Leahy on the active list for another two years. On August 1, 1939 Leahy formally handed the position of CNO over to Admiral Harold Stark

Harold Mead Stark (born August 6, 1939 in Los Angeles, California)

is an American mathematician, specializing in number theory. He is best known for his solution of the Gauss class number 1 problem, in effect correcting and completing the earl ...

.

Government service

Governor of Puerto Rico

From September 1939 to November 1940, Leahy served as Governor of Puerto Rico after Roosevelt removed

From September 1939 to November 1940, Leahy served as Governor of Puerto Rico after Roosevelt removed Blanton Winship

Blanton C. Winship (November 23, 1869 – October 9, 1947) was an American military lawyer and veteran of both the Spanish–American War and World War I. During his career, he served both as Judge Advocate General of the United States Army and ...

for his role in the Ponce massacre

The Ponce massacre was an event that took place on Palm Sunday, March 21, 1937, in Ponce, Puerto Rico, when a peaceful civilian march turned into a police shooting in which 19 civilians and two policemen were killed, and more than 200 civilians ...

. Winship had aligned himself with the Coalición, a pro-American electoral alliance that represented the interests of the island's wealthy elite and American sugar corporations. Roosevelt gave Leahy both military and social objectives to carry out: on the military side, he had to develop and upgrade base installations there; on the social side, he had to alleviate the extreme poverty and inequality that afflicted the island. To tackle these problems, Leahy was given an additional $10 million (equivalent to $ million in ) and extraordinary latitude in spending it. Leahy was named as the head of the Puerto Rican office of the Works Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; renamed in 1939 as the Work Projects Administration) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to carry out public works projects, i ...

(WPA), which gave him control over New Deal funding. In October 1939, he also became the head of the Puerto Rico Cement Corporation in order to help it secure a $700,000 loan () from the Federal government's Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), and in December he became the head of the Puerto Rican branch of the RFC. His power was enhanced by his direct access to the President and the Secretary of the interior, Harold L. Ickes

Harold LeClair Ickes ( ; March 15, 1874 – February 3, 1952) was an American administrator, politician and lawyer. He served as United States Secretary of the Interior for nearly 13 years from 1933 to 1946, the longest tenure of anyone to hold th ...

.

Although given the unflattering sobriquet ''Almirante Lija'' ("Admiral Sandpaper") by locals, based on his surname, Leahy was regarded as one of the most lenient American governors of the several who served Puerto Rico in the first half of the 20th century. He took an open stance of not intervening directly in local politics

Local government is a generic term for the lowest tiers of public administration within a particular sovereign state. This particular usage of the word government refers specifically to a level of administration that is both geographically-loca ...

, although he remained involved in Federal politics, doing what he could to support Roosevelt's 1940 reelection. He attempted to understand and respect local customs, and initiated various major public works projects. Although his priority was developing Puerto Rico as a military base, over half the WPA funds were spent on public works such as roads and improving sanitation. He regulated prices and production in the coffee industry, and had ships traveling between the United States and the Panama Canal, where major upgrade works were being undertaken, stop over in Puerto Rico when they needed repairs or supplies. In December 1939 he met with Roosevelt and secured an additional $100 million in WPA funding (equivalent to $ million in ) for public works, which allowed him to hire another 20,000 workers. By awarding lucrative government contracts and appointing officials based on Roosevelt's preferences rather than those of the local elite, he soon earned the enmity of the Coalición.

Leahy oversaw the development of military bases and stations across the island. At the time of his appointment as governor, the only naval installations were a radio station and a hydrographic office. On October 30, 1939, a fixed fee contract was awarded for construction of the Naval Air Station Isla Grande. Subsequently the scope of activity was widened to include the

Leahy oversaw the development of military bases and stations across the island. At the time of his appointment as governor, the only naval installations were a radio station and a hydrographic office. On October 30, 1939, a fixed fee contract was awarded for construction of the Naval Air Station Isla Grande. Subsequently the scope of activity was widened to include the Roosevelt Roads Naval Station

Roosevelt Roads Naval Station is a former United States Navy base in the town of Ceiba, Puerto Rico. The site operates today as José Aponte de la Torre Airport, a public use airport.

History

In 1919, future US President Franklin D. Roosev ...

. The naval air station was intended to support two squadrons of seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of taking off and landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their technological characteri ...

s and a carrier air group

A carrier air wing (abbreviated CVW) is an operational naval aviation organization composed of several aircraft squadrons and detachments of various types of fixed-wing and rotary-wing aircraft. Organized, equipped and trained to conduct mod ...

. The Isla Grande site included an existing Pan Am

Pan American World Airways, originally founded as Pan American Airways and commonly known as Pan Am, was an American airline that was the principal and largest international air carrier and unofficial overseas flag carrier of the United States ...

airstrip and a quarantine station, but most of it was mangrove swamp and tidal mud flats

Mudflats or mud flats, also known as tidal flats or, in Ireland, slob or slobs, are coastal wetlands that form in intertidal areas where sediments have been deposited by tides or rivers. A global analysis published in 2019 suggested that tidal fl ...

. The site was built up with fill dredged up from the San Antonio and Martín Peña Channel

The Martín Peña Channel (Spanish: ''Caño de Martín Peña'') is a body of water in San Juan, Puerto Rico. The similarly named Martín Peña is a neighbourhood, with informal housing, adjacent to the channel.

The channel runs from San Juan B ...

s. The existing airstrip was realigned to conform to the prevailing winds, lengthened, widened, and surfaced with asphalt. A secondary runway was also built, along with a new quarantine station and hospital. Construction work on the Roosevelt Roads Naval Station commenced in 1941 under another fixed fee contract and the base was commissioned on July 15, 1943.

Between January 1 and November 1, 1940, Leahy met with Roosevelt six times. One of the most important was a lunch on October 6, 1940. Admiral James O. Richardson, the CINCUS, had been ordered to keep the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the R ...

at the conclusion of exercises there to act as a deterrent to the Japanese. Richardson protested; Pearl Harbor, he argued, was unsuitable as a base: it could not provide the needs of the fleet for an extended stay, which would affect its readiness, and was too vulnerable to a surprise attack. Leahy agreed with Richardson, but knew better than to press the matter with Roosevelt when the President's mind was made up. On February 1, 1941, Richardson was recalled and replaced as CINCUS by Admiral Husband Kimmel.

Ambassador to France

The Fall of France in June 1940 came as a shock to many Americans;Henry L. Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 – October 20, 1950) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. Over his long career, he emerged as a leading figure in U.S. foreign policy by serving in both Republican and D ...

and McGeorge Bundy described it as "the most shocking single event of the war". American security had been underwritten by Britain and France, allowing the United States to have a comparatively low amount of defense spending, and planning was based on the assumption that France would be a bulwark against Germany, as it had been in World War I, and that the United States would have ample time to mobilize industry and create armies. Now, with France gone, Germany could directly threaten the United States. On November 18, 1940, Leahy was appointed United States Ambassador to France

The United States ambassador to France is the official representative of the president of the United States to the president of France. The United States has maintained diplomatic relations with France since the American Revolution. Relations we ...

. In his message asking Leahy to accept the position, Roosevelt explained:

Leahy sailed from Puerto Rico on November 28, and arrived in New York on December 2, from whence he immediately flew to Washington, D.C., to confer with Roosevelt, who told him that he needed to gain the confidence of the French head of state, Marshal Philippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Pétain (24 April 1856 – 23 July 1951), commonly known as Philippe Pétain (, ) or Marshal Pétain (french: Maréchal Pétain), was a French general who attained the position of Marshal of France at the end of Worl ...

, and the Commander-in-Chief of the French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

, Admiral François Darlan

Jean Louis Xavier François Darlan (7 August 1881 – 24 December 1942) was a French admiral and political figure. Born in Nérac, Darlan graduated from the ''École navale'' in 1902 and quickly advanced through the ranks following his service ...

. "My major task", Leahy later recalled "was to keep the French on our side in so far as possible". The United States would give Britain all the help it could short of actually joining the war, and Leahy would convince Pétain and Darlan that it was in France's best interest that Germany be defeated. He departed Norfolk, Virginia, on December 17 on the cruiser , and reached Lisbon, Portugal, on December 30. He then traveled overland by train and car to Vichy

Vichy (, ; ; oc, Vichèi, link=no, ) is a city in the Allier department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of central France, in the historic province of Bourbonnais.

It is a spa and resort town and in World War II was the capital of ...

, where he presented his letter of credence

A letter of credence (french: Lettre de créance) is a formal diplomatic letter that designates a diplomat as ambassador to another sovereign state. Commonly known as diplomatic credentials, the letter is addressed from one head of state to anot ...

to Pétain on January 9, 1941.

The United States had some levers with which to influence the French. It supplied food and medical aid to the Vichy French

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its terr ...

regime in French North Africa

French North Africa (french: Afrique du Nord française, sometimes abbreviated to ANF) is the term often applied to the territories controlled by France in the North African Maghreb during the colonial era, namely Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. I ...

, hoping in return to moderate its collaboration with the Axis Powers. After six months of negotiations, the British agreed to permit medical supplies to be shipped through the British blockade under Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure respect for all human beings, and ...

supervision. Food was another matter; it was estimated that 22 million French people did not get enough to eat. The British believed that Germany would seize up to 58 percent of France's food crops, but Darlan blamed the British naval blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are leg ...

, arguing that the critical shortage was not of food but of fuel for its distribution, and he threatened to use the French Navy to break the blockade.

Leahy advised Roosevelt that the shipment of supplies to France would improve America's standing and stiffen Pétain's resolve to resist German demands, In his opinion, the "British blockade action which prevents the delivery of necessary foodstuffs to the inhabitants of unoccupied France is of the same order of stupidity as many other British policies in the present war." He also hoped that aid to French North Africa would strengthen the hand of General Maxime Weygand

Maxime Weygand (; 21 January 1867 – 28 January 1965) was a French military commander in World War I and World War II.

Born in Belgium, Weygand was raised in France and educated at the Saint-Cyr military academy in Paris. After graduating in 1 ...

there. Roosevelt compelled the British to accept the shipment of medicine and food intended for children, along with thousands of tons of fuel for their distribution.

American aid proved insufficient to buy French support. In May 1941, Darlan agreed to the Paris Protocols, which granted Germany access to French military bases in Syria, Tunisia, and French West Africa, and in July the French granted Japan access to bases in French Indochina

French Indochina (previously spelled as French Indo-China),; vi, Đông Dương thuộc Pháp, , lit. 'East Ocean under French Control; km, ឥណ្ឌូចិនបារាំង, ; th, อินโดจีนฝรั่งเศส, ...

, which directly threatened the American position in the Philippines. Although no German bombers had the range to bomb the United States from bases in Senegal, if they could deploy from Senegal to Vichy-held Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in ...

, they could do so from there. Weygand, the main American hope for a change in French policy, was recalled on November 18, despite Leahy's warnings that this could prompt a cession of American aid. On December 7, 1941, Leahy received news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, ju ...

. This was followed, on December 11, by the German declaration of war against the United States

On 11 December 1941, four days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the United States declaration of war against the Japanese Empire, Nazi Germany declared war against the United States, in response to what was claimed to be a serie ...

. With the United States now in the war, Leahy thought that this would strengthen his hand with the Vichy government, but Charles de Gaulle's capture of Saint Pierre and Miquelon later that month discredited American assurances that French colonies would not be seized.

By this time Leahy was convinced that the United States was backing the wrong side, and he urged Roosevelt to use this as a pretext for recalling him to the United States. This was finally prompted by the formation of a new government in Vichy under the pro-Axis Pierre Laval

Pierre Jean Marie Laval (; 28 June 1883 – 15 October 1945) was a French politician. During the Third Republic, he served as Prime Minister of France from 27 January 1931 to 20 February 1932 and 7 June 1935 to 24 January 1936. He again occ ...

on April 18. Meanwhile, on April 9, Leahy's wife Louise underwent a hysterectomy. While recovering from the operation, she suffered an embolism

An embolism is the lodging of an embolus, a blockage-causing piece of material, inside a blood vessel. The embolus may be a blood clot (thrombus), a fat globule (fat embolism), a bubble of air or other gas ( gas embolism), amniotic fluid (am ...

and died on April 21. Leahy called on Pétain to say farewell on April 27. He arrived back in New York on the Swedish-registered ocean liner on June 1. He arranged for a funeral service for Louise at the St. Thomas Episcopal Church, where they had been members for many years, and watched her burial in Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

on June 3, 1942.

Chief of Staff to the Commander in Chief

Organization and role

Waging a two-ocean war as part of a coalition revealed serious deficiencies in the organization of the American high command when it came to formulatinggrand strategy

Grand strategy or high strategy is a state's strategy of how means can be used to advance and achieve national interests. Issues of grand strategy typically include the choice of primary versus secondary theaters in war, distribution of resource ...

: meetings of the senior officers of the Army and Navy with each other and with the President were irregular and infrequent, and there was no joint planning staff or secretariat to record decisions taken. Under the Constitution of the United States

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

, the President was the Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy. At a meeting with Roosevelt on February 24, 1942, the Chief of Staff of the United States Army

The chief of staff of the Army (CSA) is a statutory position in the United States Army held by a general officer. As the highest-ranking officer assigned to serve in the Department of the Army, the chief is the principal military advisor and ...

, General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

George C. Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the US Army under Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry ...

, urged Roosevelt to appoint a chief of staff of the armed forces to provide unity of command

In military organisation, unity of command is the principle that subordinate members of a structure should all be responsible to a single commander.

United States

The military of the United States considers unity of command as one of the twelve ...

, and he suggested Leahy for the role. Leahy had lunch with Roosevelt on July 7, during which this was discussed. On July 21, Leahy was recalled to active duty. He resigned as Ambassador to France and was appointed Chief of Staff to the Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy. In announcing the appointment, Roosevelt described Leahy's role as an advisory one rather than that of a supreme commander.

Leahy attended his first meeting of the

Leahy attended his first meeting of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, that advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and the ...

(JCS) on July 28. The other members were Marshall; King, who was now both CNO and Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet (now abbreviated as COMINCH); and Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

Henry H. Arnold

Henry Harley Arnold (June 25, 1886 – January 15, 1950) was an American general officer holding the ranks of General of the Army and later, General of the Air Force. Arnold was an aviation pioneer, Chief of the Air Corps (1938–1941), ...

, the Chief of U.S. Army Air Forces. Henceforth, the JCS held regular meetings at noon on Wednesdays, which usually commenced with a light lunch. Leahy served as the de facto chairman. He drew up the agenda for the JCS meetings, presided over them, and signed off on all the major papers and decisions. He considered that this was due to his seniority and not by virtue of his position. He had a small personal staff of two military aides-de-camp and two or three secretaries. JCS meetings were held in the Public Health Service Building, where Leahy had an office. After some renovations were made, he was also given an office in the East Wing