Is that even an essay? on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In linguistics, a copula (plural: copulas or copulae; list of glossing abbreviations, abbreviated ) is a word or phrase that links the subject (grammar), subject of a sentence (linguistics), sentence to a subject complement, such as the word ''is'' in the sentence "The sky is blue" or the phrase ''was not being'' in the sentence "It was not being co-operative." The word ''copula'' derives from the Latin noun for a "link" or "tie" that connects two different things.

A copula is often a verb or a verb-like word, though this is not universally the case. A verb that is a copula is sometimes called a copulative or copular verb. In English primary education grammar courses, a copula is often called a linking verb. In other languages, copulas show more resemblances to pronouns, as in Classical Chinese and Guarani language, Guarani, or may take the form of suffixes attached to a noun, as in Korean language, Korean, Beja language, Beja, and Inuit languages.

Most languages have one main copula, although some (like Spanish language, Spanish, Portuguese language, Portuguese and Thai language, Thai) have more than one, while others have Zero copula, none. In the case of English, this is the verb ''to be''. While the term ''copula'' is generally used to refer to such principal verbs, it may also be used for a wider group of verbs with similar potential functions (like ''become'', ''get'', ''feel'' and ''seem'' in English); alternatively, these might be distinguished as "semi-copulas" or "pseudo-copulas".

jest' '', even though the Germanic, Italic, Iranian and Slavic language groups split at least 3000 years ago. The origins of the copulas of most Indo-European languages can be traced back to four Proto-Indo-European language, Proto-Indo-European stems: ''*es-'' (''*h1es-''), ''*sta-'' (''*steh2-''), ''*wes-'' and ''*bhu-'' (''*bʰuH-'').

The Japanese language, Japanese copula (most often translated into English as an inflected form of "to be") has many forms. E.g., The form ''da'' is used predicate (grammar), predicatively, ''na'' - Attributive verb, attributively, ''de'' - adverbially or as a connector, and ''desu'' - predicatively or as a politeness indicator.

Examples:

:

''desu'' is the Honorific speech in Japanese, polite form of the copula. Thus, many sentences like the ones below are almost identical in meaning and differ only in the speaker's politeness to the Interlocutor (linguistics), addressee and in nuance of how assured the person is of their statement.

:

A predicate in Japanese is expressed by the predicative form of a verb, the predicative form of an adjective or noun + the predicative form of a copula.

:

Other forms of copula:

である ''de aru'', であります ''de arimasu'' (used in writing and formal speaking)

でございます ''de gozaimasu'' (used in public announcements, notices, etc.)

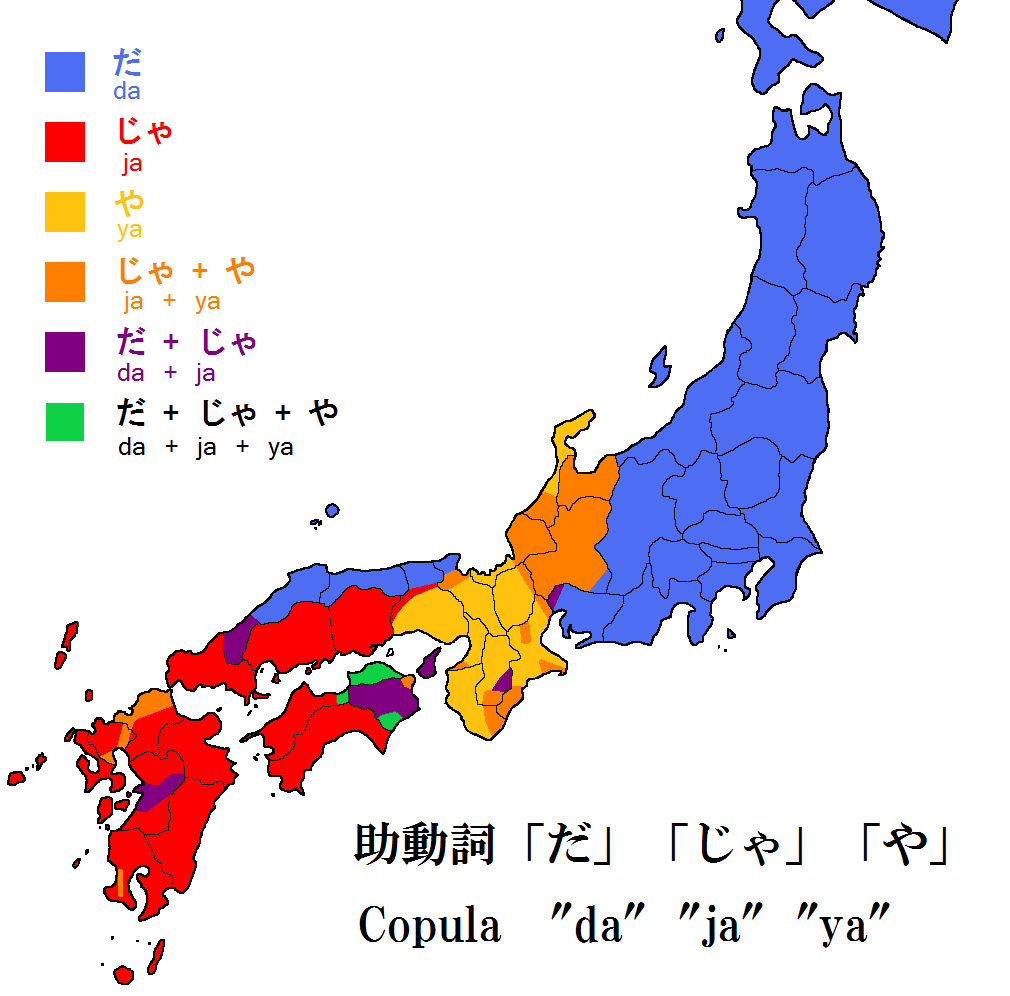

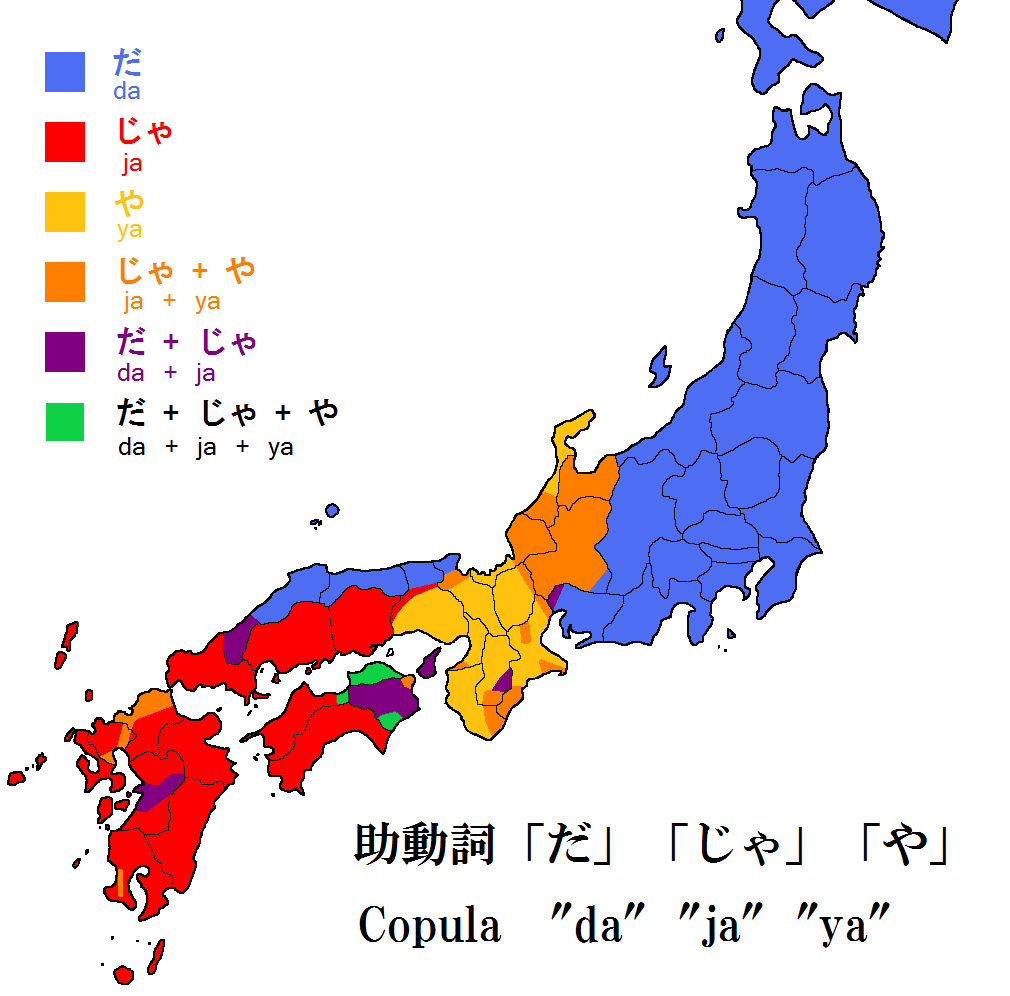

The copula is subject to dialectal variation throughout Japan, resulting in forms like や ''ya'' in Kansai dialect, Kansai and じゃ ''ja'' in Hiroshima (see map above).

Japanese also has two verbs corresponding to English "to be": ''aru'' and ''iru''. They are not copulas but existential verbs. ''Aru'' is used for inanimate objects, including plants, whereas ''iru'' is used for animate things like people, animals, and robots, though there are exceptions to this generalization.

:

Japanese language, Japanese speakers, when learning English, often drop the auxiliary verbs "be" and "do," incorrectly believing that "be" is a semantically empty copula equivalent to "desu" and "da."

The Japanese language, Japanese copula (most often translated into English as an inflected form of "to be") has many forms. E.g., The form ''da'' is used predicate (grammar), predicatively, ''na'' - Attributive verb, attributively, ''de'' - adverbially or as a connector, and ''desu'' - predicatively or as a politeness indicator.

Examples:

:

''desu'' is the Honorific speech in Japanese, polite form of the copula. Thus, many sentences like the ones below are almost identical in meaning and differ only in the speaker's politeness to the Interlocutor (linguistics), addressee and in nuance of how assured the person is of their statement.

:

A predicate in Japanese is expressed by the predicative form of a verb, the predicative form of an adjective or noun + the predicative form of a copula.

:

Other forms of copula:

である ''de aru'', であります ''de arimasu'' (used in writing and formal speaking)

でございます ''de gozaimasu'' (used in public announcements, notices, etc.)

The copula is subject to dialectal variation throughout Japan, resulting in forms like や ''ya'' in Kansai dialect, Kansai and じゃ ''ja'' in Hiroshima (see map above).

Japanese also has two verbs corresponding to English "to be": ''aru'' and ''iru''. They are not copulas but existential verbs. ''Aru'' is used for inanimate objects, including plants, whereas ''iru'' is used for animate things like people, animals, and robots, though there are exceptions to this generalization.

:

Japanese language, Japanese speakers, when learning English, often drop the auxiliary verbs "be" and "do," incorrectly believing that "be" is a semantically empty copula equivalent to "desu" and "da."

''The Raising of Predicates''

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England. * * Tüting, A. W. (December 2003).

Essay on Lakota syntax

'. . *

Grammatical function

The principal use of a copula is to link the subject (grammar), subject of a clause (grammar), clause to a subject complement. A copular verb is often considered to be part of the predicate (grammar), predicate, the remainder being called a predicative expression. A simple clause containing a copula is illustrated below:The book is on the table.In that sentence, the noun phrase ''the book'' is the subject, the verb ''is'' serves as the copula, and the prepositional phrase ''on the table'' is the predicative expression. The whole expression ''is on the table'' may (in some theories of grammar) be called a predicate or a verb phrase. The predicative expression accompanying the copula, also known as the complement (grammar), complement of the copula, may take any of several possible forms: it may be a noun or noun phrase, an adjective or adjective phrase, a prepositional phrase (as above) or an adverb or another adverbial phrase expressing time or location. Examples are given below (with the copula in bold and the predicative expression in italics): The three components (subject, copula and predicative expression) do not necessarily appear in that order: their positioning depends on the rules for word order applicable to the language in question. In English (an subject-verb-object, SVO language), the ordering given above is the normal one, but certain variation is possible: *In many questions and other clauses with subject–auxiliary inversion, the copula moves in front of the subject: ''Are you happy?'' *In inverse copular constructions (see below) the predicative expression precedes the copula, but the subject follows it: ''In the room were three men.'' It is also possible, in certain circumstances, for one (or even two) of the three components to be absent: *In null-subject language, null-subject (pro-drop) languages, the subject may be omitted, as it may from other types of sentence. In Italian language, Italian, means ‘I am tired’, literally ‘am tired’. *In non-finite clauses in languages like English, the subject is often absent, as in the participial phrase ''being tired'' or the infinitive phrase ''to be tired''. The same applies to most imperative sentences like ''Be good!'' *For cases in which no copula appears, see below. *Any of the three components may be omitted as a result of various general types of ellipsis (grammar), ellipsis. In particular, in English, the predicative expression may be elided in a construction similar to verb phrase ellipsis, as in short sentences like ''I am''; ''Are they?'' (where the predicative expression is understood from the previous context). Inverse copular constructions, in which the positions of the predicative expression and the subject are reversed, are found in various languages. They have been the subject of much theoretical analysis, particularly in regard to the difficulty of maintaining, in the case of such sentences, the usual division into a subject noun phrase and a predicate verb phrase. Another issue is agreement (linguistics), verb agreement when both subject and predicative expression are noun phrases (and differ in number or person): in English, the copula typically agrees with the syntactical subject even if it is not logically (i.e. semantics, semantically) the subject, as in ''the cause of the riot is'' (not ''are'') ''these pictures of the wall''. Compare Italian ; notice the use of the plural to agree with plural "these photos" rather than with singular "the cause". In instances where an English syntactical subject comprises a prepositional object that is pluralized, however, the prepositional object agrees with the predicative expression, e.g. "What kind ''of birds are'' those?" The definition and scope of the concept of a copula is not necessarily precise in any language. As noted above, though the concept of the copula in English is most strongly associated with the verb ''to be'', there are many other verbs that can be used in a copular sense as well. * The boy became a man. * The girl grew more excited as the holiday preparations intensified. * The dog felt tired from the activity. And more tenuously * The milk turned sour. * The food smells good. * You seem upset.

Meanings

Predicates formed using a copula may express identity: that the two noun phrases (subject and complement) have the same referent or express an identical concept: They may also express membership of a class or a subset relationship: Similarly they may express some property, relation or position, permanent or temporary: Other special uses of copular verbs are described in some of the following sections.Essence vs. state

Some languages use different copulas, or different syntax, to denote a permanent, essential characteristic of something versus a temporary state. For examples, see the sections on the #Romance, Romance languages, #Slavic, Slavic languages and #Irish, Irish.Forms

In many languages the principal copula is a verb, like English ''(to) be'', German , Mixtec language, Mixtec , Tuareg languages, Touareg ''emous'', etc. It may inflect for grammatical category, grammatical categories like grammatical tense, tense, grammatical aspect, aspect and grammatical mood, mood, like other verbs in the language. Being a very commonly used verb, it is likely that the copula has irregular verb, irregular inflected forms; in English, the verb ''be'' has a number of highly irregular (suppletion, suppletive) forms and has more different inflected forms than any other English verb (''am'', ''is'', ''are'', ''was'', ''were'', etc.; see English verbs for details). Other copulas show more resemblances to pronouns. That is the case for Classical Chinese and Guarani language, Guarani, for instance. In highly synthetic languages, copulas are often suffixes, attached to a noun, but they may still behave otherwise like ordinary verbs: in Inuit languages. In some other languages, like Beja language, Beja and Ket language, Ket, the copula takes the form of suffixes that attach to a noun but are distinct from the grammatical conjugation, person agreement markers used on predicative verbs. This phenomenon is known as ''nonverbal person agreement'' (or ''nonverbal subject agreement''), and the relevant markers are always established as deriving from cliticized independent pronouns. For cases in which the copula is omitted or takes zero (linguistics), zero form, see below.Additional uses of copular verbs

A copular verb may also have other uses supplementary to or distinct from its uses as a copula.As auxiliary verbs

The English verb ''to be'' is also used as an English auxiliaries, auxiliary verb, especially for expressing passive voice (together with the past participle) or expressing progressive aspect (together with the present participle): Other languages' copulas have additional uses as auxiliaries. For example, French can be used to express passive voice similarly to English ''be''; both French and German are used to express the Perfect (grammar), perfect forms of certain verbs (formerly English ''be'' was also): The auxiliary functions of these verbs derived from their copular function, and could be interpreted as special cases of the copular function (with the verbal forms it precedes being considered adjectival). Another auxiliary usage in English is (together with the to-infinitive, ''to''-infinitive) to denote an obligatory action or expected occurrence: "I am to serve you;" "The manager is to resign." This can be put also into past tense: "We were to leave at 9." For forms like "if I was/were to come," see English conditional sentences. (Note that, by certain criteria, the English copula ''be'' may always be considered an auxiliary verb; see Auxiliary verb#Diagnostics for identifying auxiliary verbs in English, Diagnostics for identifying auxiliary verbs in English.)Existential usage

The English ''to be'' and its equivalents in certain other languages also have a non-copular use as an existential verb, meaning "to exist." This use is illustrated in the following sentences: ''I want only to be, and that is enough''; ''Cogito ergo sum, I think therefore I am''; ''To be, or not to be, To be or not to be, that is the question.'' In these cases, the verb itself expresses a predicate (that of existence), rather than linking to a predicative expression as it does when used as a copula. In ontology it is sometimes suggested that the "is" of existence is reducible to the "is" of property attribution or class membership; to be, Aristotle held, is to be ''something''. However, Abelard in his ''Dialectica'' made a ''reductio ad absurdum'' argument against the idea that the copula can express existence. Similar examples can be found in many other languages; for example, the French and Latin equivalents of ''I think therefore I am'' are and , where and are the equivalents of English "am," normally used as copulas. However, other languages prefer a different verb for existential use, as in the Spanish version (where the verb "to exist" is used rather than the copula or ‘to be’). Another type of existential usage is in clauses of the ''there is…'' or ''there are…'' type. Languages differ in the way they express such meanings; some of them use the copular verb, possibly with an expletive pronoun like the English ''there'', while other languages use different verbs and constructions, like the French (which uses parts of the verb ‘to have,’ not the copula) or the Swedish (the passive voice of the verb for "to find"). For details, see existential clause. Relying on a unified theory of copular sentences, it has been proposed that the English ''there''-sentences are subtypes of inverse copular constructions.Zero copula

In some languages, copula omission occurs within a particular grammatical context. For example, speakers of Russian language, Russian, Indonesian language, Indonesian, Turkish language, Turkish, Hungarian language, Hungarian, Arabic language, Arabic, Hebrew language, Hebrew, Geʽez and Quechuan languages consistently drop the copula in present tense: Russian: , ‘I (am a) person;’ Indonesian: ‘I (am) a human;’ Turkish: ‘s/he (is a) human;’ Hungarian: ‘s/he (is) a human;’ Arabic: أنا إنسان, ‘I (am a) human;’ Hebrew: אני אדם, ''ʔani ʔadam'' "I (am a) human;" Geʽez: አነ ብእሲ/ብእሲ አነ ''ʔana bəʔəsi'' / ''bəʔəsi ʔana'' "I (am a) man" / "(a) man I (am)"; Southern Quechua: ''payqa runam'' "s/he (is) a human." The usage is known generically as the zero copula. Note that in other tenses (sometimes in forms other than third person singular), the copula usually reappears. Some languages drop the copula in poetic or aphorismic contexts. Examples in English include * ''The more, the better.'' * ''Out of many, one.'' * ''True that.'' Such poetic copula dropping is more pronounced in some languages other than English, like the Romance languages. In informal speech of English, the copula may also be dropped in general sentences, as in "She a nurse." It is a feature of African-American Vernacular English, but is also used by a variety of other English speakers in informal contexts. An example is the sentence "I saw twelve men, each a soldier."Examples in specific languages

In Ancient Greek, when an adjective precedes a noun with an article, the copula is understood: , "the house is large," can be written , "large the house (is)." In Quechua (Southern Quechua used for the examples), zero copula is restricted to present tense in third person singular (''kan''): ''Payqa runam'' — "(s)he is a human;" but: ''(paykuna) runakunam kanku'' "(they) are human."ap In Māori language, Māori, the zero copula can be used in predicative expressions and with continuous verbs (many of which take a copulative verb in many Indo-European languages) — ''He nui te whare'', literally "a big the house," "the house (is) big;" ''I te tēpu te pukapuka'', literally "at (past locative particle) the table the book," "the book (was) on the table;" ''Nō Ingarangi ia'', literally "from England (s)he," "(s)he (is) from England," ''Kei te kai au'', literally "at the (act of) eating I," "I (am) eating." Alternatively, in many cases, the particle ''ko'' can be used as a copulative (though not all instances of ''ko'' are used as thus, like all other Maori particles, ''ko'' has multiple purposes): ''Ko nui te whare'' "The house is big;" ''Ko te pukapuka kei te tēpu'' "It is the book (that is) on the table;" ''Ko au kei te kai'' "It is me eating." However, when expressing identity or class membership, ''ko'' must be used: ''Ko tēnei tāku pukapuka'' "This is my book;" ''Ko Ōtautahi he tāone i Te Waipounamu'' "Christchurch is a city in the South Island (of New Zealand);" ''Ko koe tōku hoa'' "You are my friend." When expressing identity, ''ko'' can be placed on either object in the clause without changing the meaning (''ko tēnei tāku pukapuka'' is the same as ''ko tāku pukapuka tēnei'') but not on both (''ko tēnei ko tāku pukapuka'' would be equivalent to saying "it is this, it is my book" in English). In Hungarian, zero copula is restricted to present tense in third person singular and plural: ''Ő ember''/''Ők emberek'' — "s/he is a human"/"they are humans;" but: ''(én) ember vagyok'' "I am a human," ''(te) ember vagy'' "you are a human," ''mi emberek vagyunk'' "we are humans," ''(ti) emberek vagytok'' "you (all) are humans." The copula also reappears for stating locations: ''az emberek a házban vannak'', "the people are in the house," and for stating time: ''hat óra van'', "it is six o'clock." However, the copula may be omitted in colloquial language: ''hat óra (van)'', "it is six o'clock." Hungarian uses copula ''lenni'' for expressing location: ''Itt van Róbert'' "Bob is here," but it is omitted in the third person present tense for attribution or identity statements: ''Róbert öreg'' "Bob is old;" ''ők éhesek'' "They are hungry;" ''Kati nyelvtudós'' "Cathy is a linguist" (but ''Róbert öreg volt'' "Bob was old," ''éhesek voltak'' "They were hungry," ''Kati nyelvtudós volt'' "Cathy was a linguist). In Turkish, both the third person singular and the third person plural copulas are omittable. ''Ali burada'' and ''Ali buradadır'' both mean "Ali is here," and ''Onlar aç'' and ''Onlar açlar'' both mean "They are hungry." Both of the sentences are acceptable and grammatically correct, but sentences with the copula are more formal. The Turkish first person singular copula suffix is omitted when introducing oneself. ''Bora ben'' (I am Bora) is grammatically correct, but "Bora benim" (same sentence with the copula) is not for an introduction (but is grammatically correct in other cases). Further restrictions may apply before omission is permitted. For example, in the Irish language, ''is'', the present tense of the copula, may be omitted when the predicate (grammar), predicate is a noun. ''Ba'', the past/conditional, cannot be deleted. If the present copula is omitted, the pronoun (e.g., ''é, í, iad'') preceding the noun is omitted as well.Additional copulas

Sometimes, the term ''copula'' is taken to include not only a language's equivalent(s) to the verb ''be'' but also other verbs or forms that serve to link a subject to a predicative expression (while adding semantic content of their own). For example, English verbs like ''become'', ''get'', ''feel'', ''look'', ''taste'', ''smell'', and ''seem'' can have this function, as in the following sentences (the predicative expression, the complement of the verb, is in italics): (This usage should be distinguished from the use of some of these verbs as "action" verbs, as in ''They look at the wall'', in which ''look'' denotes an action and cannot be replaced by the basic copula ''are''.) Some verbs have rarer, secondary uses as copular verbs, like the verb ''fall'' in sentences like ''The zebra fell victim to the lion.'' These extra copulas are sometimes called "semi-copulas" or "pseudo-copulas." For a list of common verbs of this type in English, see List of English copulae.In particular languages

Indo-European

In Indo-European languages, the words meaning ''to be'' are sometimes similar to each other. Due to the high frequency of their use, their inflection retains a considerable degree of similarity in some cases. Thus, for example, the English form ''is'' is a cognate of German ''ist'', Latin ''est'', Persian ''ast'' and Russian ''English

The English copular verb ''be'' has eight forms (more than any other English verb): ''be'', ''am'', ''is'', ''are'', ''being'', ''was'', ''were'', ''been''. Additional archaic forms include ''art'', ''wast'', ''wert'', and occasionally ''beest'' (as a English subjunctive, subjunctive). For more details see English verbs. For the etymology of the various forms, see Indo-European copula. The main uses of the copula in English are described in the above sections. The possibility of copula omission is mentioned under . A particular construction found in English (particularly in speech) is the use of double copula, two successive copulas when only one appears necessary, as in ''My point is, is that...''. The acceptability of this construction is a English usage controversies, disputed matter in English prescriptive grammar. The simple English copula "be" may on occasion be substituted by other verbs with near identical meanings.Persian

In Persian, the verb ''to be'' can either take the form of ''ast'' (cognate to English ''is'') or ''budan'' (cognate to ''be''). :Hindustani

In Hindustani grammar, Hindustani (Hindi and Urdu), the copula होना ɦonɑ ہونا can be put into four grammatical aspects (simple, habitual, perfective, and progressive) and each of those four aspects can be put into five grammatical moods (indicative, presumptive, subjunctive, contrafactual, and imperative). Some example sentences using the simple aspect are shown below: Besides the verb होना honā (to be), there are three other verbs which can also be used as the copula, they are रहना rêhnā (to stay), जाना jānā (to go), and आना ānā (to come). The following table shows the conjugations of the copula होना honā in the five grammatical moods in the simple aspect. The transliteration scheme used is ISO 15919.Romance

Copulas in the Romance languages usually consist of two different verbs that can be translated as "to be," the main one from the Latin ''esse'' (via Vulgar Latin ''essere''; ''esse'' deriving from ''*es-''), often referenced as ''sum'' (another of the Latin verb's principal parts) and a secondary one from ''stare'' (from ''*sta-''), often referenced as ''sto''. The resulting distinction in the modern forms is found in all the Iberian Romance languages, and to a lesser extent Italian, but not in French or Romanian. The difference is that the first usually refers to essential characteristics, while the second refers to states and situations, e.g., "Bob is old" versus "Bob is well." A similar division is found in the non-Romance Basque language (viz. ''egon'' and ''izan''). (Note that the English words just used, "essential" and "state," are also cognate with the Latin infinitives ''esse'' and ''stare''. The word "stay" also comes from Latin stare, through Middle French ''estai'', stem of Old French ''ester''.) In Spanish and Portuguese, the high degree of verbal inflection, plus the existence of two copulas (''ser'' and ''estar''), means that there are 105 (Spanish) and 110 (Portuguese) separate forms to express the copula, compared to eight in English and one in Chinese. In some cases, the verb itself changes the meaning of the adjective/sentence. The following examples are from Portuguese:Slavic

Some Slavic languages make a distinction between essence and state (similar to that discussed in the above section on the #Romance, Romance languages), by putting a predicative expression denoting a state into the instrumental case, and essential characteristics are in the nominative case, nominative. This can apply with other copula verbs as well: the verbs for "become" are normally used with the instrumental case. As noted above under , Russian and other East Slavic languages generally omit the copula in the present tense.Irish

In Irish language, Irish and Scottish Gaelic, there are two copulas, and the syntax is also changed when one is distinguishing between states or situations and essential characteristics. Describing the subject's state or situation typically uses the normal verb–subject–object, VSO ordering with the verb ''bí''. The copula ''is'' is used to state essential characteristics or equivalences. : The word ''is'' is the copula (rhymes with the English word "miss"). The pronoun used with the copula is different from the normal pronoun. For a masculine singular noun, ''é'' is used (for "he" or "it"), as opposed to the normal pronoun ''sé''; for a feminine singular noun, ''í'' is used (for "she" or "it"), as opposed to normal pronoun ''sí''; for plural nouns, ''iad'' is used (for "they" or "those"), as opposed to the normal pronoun ''siad''. To describe being in a state, condition, place, or act, the verb "to be" is used: ''Tá mé ag rith.'' "I am running."Arabic dialects

North Levantine Arabic

The North Levantine Arabic dialect, spoken in Syria and Lebanon, has a Copula (linguistics), negative copula formed by and a suffixed pronoun.Bantu languages

Chichewa

In Chewa language, Chichewa, a Bantu languages, Bantu language spoken mainly in Malawi, a very similar distinction exists between permanent and temporary states as in Spanish and Portuguese, but only in the present tense. For a permanent state, in the 3rd person, the copula used in the present tense is ''ndi'' (negative ''sí''): :''iyé ndi mphunzitsi'' "he is a teacher" :''iyé sí mphunzitsi'' "he is not a teacher" For the 1st and 2nd persons the particle ''ndi'' is combined with pronouns, e.g. ''ine'' "I": :''ine ndine mphunzitsi'' "I am a teacher" :''iwe ndiwe mphunzitsi'' "you (singular) are a teacher" :''ine síndine mphunzitsi'' "I am not a teacher" For temporary states and location, the copula is the appropriate form of the defective verb ''-li'': :''iyé ali bwino'' "he is well" :''iyé sáli bwino'' "he is not well" :''iyé ali ku nyumbá'' "he is in the house" For the 1st and 2nd persons the person is shown, as normally with Chichewa verbs, by the appropriate pronominal prefix: :''ine ndili bwino'' "I am well" :''iwe uli bwino'' "you (sg.) are well" :''kunyumbá kuli bwino'' "at home (everything) is fine" In the past tenses, ''-li'' is used for both types of copula: :''iyé analí bwino'' "he was well (this morning)" :''iyé ánaalí mphunzitsi'' "he was a teacher (at that time)" In the future, subjunctive, or conditional tenses, a form of the verb ''khala'' ("sit/dwell") is used as a copula: :''máwa ákhala bwino'' "he'll be fine tomorrow"Muylaq' Aymaran

Uniquely, the existence of the copulative verbalizer suffix in the Southern Peruvian Aymara language, Aymaran language variety, Muylaq' Aymara, is evident only in the surfacing of a vowel that would otherwise have been deleted because of the presence of a following suffix, lexically prespecified to suppress it. As the copulative verbalizer has no independent phonetic structure, it is represented by the Greek letter ʋ in the examples used in this entry. Accordingly, unlike in most other Aymaran variants, whose copulative verbalizer is expressed with a vowel-lengthening component, -'':'', the presence of the copulative verbalizer in Muylaq' Aymara is often not apparent on the surface at all and is analyzed as existing only meta-linguistically. However, it is also relevant to note that in a verb phrase like "It is old," the noun ''thantha'' meaning "old" does not require the copulative verbalizer, ''thantha-wa'' "It is old." It is now pertinent to make some observations about the distribution of the copulative verbalizer. The best place to start is with words in which its presence or absence is obvious. When the vowel-suppressing first person simple tense suffix attaches to a verb, the vowel of the immediately preceding suffix is suppressed (in the examples in this subsection, the subscript "c" appears prior to vowel-suppressing suffixes in the interlinear gloss to better distinguish instances of Vowel deletion, deletion that arise from the presence of a lexically pre-specified suffix from those that arise from other (e.g. phonotactic) motivations). Consider the verb ''sara''- which is inflected for the first person simple tense and so, predictably, loses its final root vowel: ''sar(a)-ct-wa'' "I go." However, prior to the suffixation of the first person simple suffix -''ct'' to the same root nominalized with the agentive nominalizer -''iri'', the word must be verbalized. The fact that the final vowel of -''iri'' below is not suppressed indicates the presence of an intervening segment, the copulative verbalizer: ''sar(a)-iri-ʋ-t-wa'' "I usually go." It is worthwhile to compare of the copulative verbalizer in Muylaq' Aymara as compared to La Paz Aymara, a variant which represents this suffix with vowel lengthening. Consider the near-identical sentences below, both translations of "I have a small house" in which the nominal root ''uta-ni'' "house-attributive" is verbalized with the copulative verbalizer, but note that the correspondence between the copulative verbalizer in these two variants is not always a strict one-to-one relation. :Georgian

As in English, the verb "to be" (''qopna'') is irregular in Georgian language, Georgian (a South Caucasian languages, Kartvelian language); different verb roots are employed in different tenses. The roots -''ar''-, -''kn''-, -''qav''-, and -''qop''- (past participle) are used in the present tense, future tense, past tense and the perfective tenses respectively. Examples: : Note that, in the last two examples (perfective and pluperfect), two roots are used in one verb compound. In the perfective tense, the root ''qop'' (which is the expected root for the perfective tense) is followed by the root ''ar'', which is the root for the present tense. In the pluperfective tense, again, the root ''qop'' is followed by the past tense root ''qav''. This formation is very similar to German language, German (an Indo-European languages, Indo-European language), where the perfect and the pluperfect are expressed in the following way: : Here, ''gewesen'' is the past participle of ''sein'' ("to be") in German. In both examples, as in Georgian, this participle is used together with the present and the past forms of the verb in order to conjugate for the perfect and the pluperfect aspects.Haitian Creole

Haitian Creole language, Haitian Creole, a French-based creole language, has three forms of the copula: ''se'', ''ye'', and the zero copula, no word at all (the position of which will be indicated with ''Ø'', just for purposes of illustration). Although no textual record exists of Haitian-Creole at its earliest stages of development from French, ''se'' is derived from French (written ''c'est''), which is the normal French contraction of (that, written ''ce'') and the copula (is, written ''est'') (a form of the verb ''être''). The derivation of ''ye'' is less obvious; but we can assume that the French source was ("he/it is," written ''il est''), which, in rapidly spoken French, is very commonly pronounced as (typically written ''y est''). The use of a zero copula is unknown in French, and it is thought to be an innovation from the early days when Haitian-Creole was first developing as a Romance-based pidgin. Latin also sometimes used a zero copula. Which of ''se'' / ''ye'' / ''Ø'' is used in any given copula clause depends on complex syntactic factors that we can superficially summarize in the following four rules: 1. Use ''Ø'' (i.e., no word at all) in declarative sentences where the complement is an adjective phrase, prepositional phrase, or adverb phrase: : 2. Use ''se'' when the complement is a noun phrase. But note that, whereas other verbs come ''after'' any tense/mood/aspect particles (like ''pa'' to mark negation, or ''te'' to explicitly mark past tense, or ''ap'' to mark progressive aspect), ''se'' comes ''before'' any such particles: : 3. Use ''se'' where French and English have a dummy pronoun, dummy "it" subject: : 4. Finally, use the other copula form ''ye'' in situations where the sentence's syntax leaves the copula at the end of a phrase: : The above is, however, only a simplified analysis.Japanese

The Japanese language, Japanese copula (most often translated into English as an inflected form of "to be") has many forms. E.g., The form ''da'' is used predicate (grammar), predicatively, ''na'' - Attributive verb, attributively, ''de'' - adverbially or as a connector, and ''desu'' - predicatively or as a politeness indicator.

Examples:

:

''desu'' is the Honorific speech in Japanese, polite form of the copula. Thus, many sentences like the ones below are almost identical in meaning and differ only in the speaker's politeness to the Interlocutor (linguistics), addressee and in nuance of how assured the person is of their statement.

:

A predicate in Japanese is expressed by the predicative form of a verb, the predicative form of an adjective or noun + the predicative form of a copula.

:

Other forms of copula:

である ''de aru'', であります ''de arimasu'' (used in writing and formal speaking)

でございます ''de gozaimasu'' (used in public announcements, notices, etc.)

The copula is subject to dialectal variation throughout Japan, resulting in forms like や ''ya'' in Kansai dialect, Kansai and じゃ ''ja'' in Hiroshima (see map above).

Japanese also has two verbs corresponding to English "to be": ''aru'' and ''iru''. They are not copulas but existential verbs. ''Aru'' is used for inanimate objects, including plants, whereas ''iru'' is used for animate things like people, animals, and robots, though there are exceptions to this generalization.

:

Japanese language, Japanese speakers, when learning English, often drop the auxiliary verbs "be" and "do," incorrectly believing that "be" is a semantically empty copula equivalent to "desu" and "da."

The Japanese language, Japanese copula (most often translated into English as an inflected form of "to be") has many forms. E.g., The form ''da'' is used predicate (grammar), predicatively, ''na'' - Attributive verb, attributively, ''de'' - adverbially or as a connector, and ''desu'' - predicatively or as a politeness indicator.

Examples:

:

''desu'' is the Honorific speech in Japanese, polite form of the copula. Thus, many sentences like the ones below are almost identical in meaning and differ only in the speaker's politeness to the Interlocutor (linguistics), addressee and in nuance of how assured the person is of their statement.

:

A predicate in Japanese is expressed by the predicative form of a verb, the predicative form of an adjective or noun + the predicative form of a copula.

:

Other forms of copula:

である ''de aru'', であります ''de arimasu'' (used in writing and formal speaking)

でございます ''de gozaimasu'' (used in public announcements, notices, etc.)

The copula is subject to dialectal variation throughout Japan, resulting in forms like や ''ya'' in Kansai dialect, Kansai and じゃ ''ja'' in Hiroshima (see map above).

Japanese also has two verbs corresponding to English "to be": ''aru'' and ''iru''. They are not copulas but existential verbs. ''Aru'' is used for inanimate objects, including plants, whereas ''iru'' is used for animate things like people, animals, and robots, though there are exceptions to this generalization.

:

Japanese language, Japanese speakers, when learning English, often drop the auxiliary verbs "be" and "do," incorrectly believing that "be" is a semantically empty copula equivalent to "desu" and "da."

Korean

For sentences with predicate nominatives, the copula "이" (i-) is added to the predicate nominative (with no space in between). : Some adjectives (usually colour adjectives) are nominalized and used with the copula "이"(i-). 1. Without the copula "이"(i-): : 2. With the copula "이"(i-): : Some Korean adjectives are derived using the copula. Separating these articles and nominalizing the former part will often result in a sentence with a related, but different meaning. Using the separated sentence in a situation where the un-separated sentence is appropriate is usually acceptable as the listener can decide what the speaker is trying to say using the context.Chinese

N.B. The characters used are Simplified Chinese, simplified ones, and the transcriptions given in italics reflect Standard Chinese pronunciation, using the pinyin system. In Chinese language, Chinese, both states and qualities are, in general, expressed with stative verbs (SV) with no need for a copula, e.g., in Traditional Chinese, Chinese, "to be tired" (累 ''lèi''), "to be hungry" (饿 ''è''), "to be located at" (在 ''zài''), "to be stupid" (笨 ''bèn'') and so forth. A sentence can consist simply of a pronoun and such a verb: for example, 我饿 ''wǒ è'' ("I am hungry"). Usually, however, verbs expressing qualities are qualified by an adverb (meaning "very," "not," "quite," etc.); when not otherwise qualified, they are often preceded by 很 ''hěn'', which in other contexts means "very," but in this use often has no particular meaning. Only sentences with a noun as the complement (e.g., "This is my sister") use the copular verb "to be": . This is used frequently; for example, instead of having a verb meaning "to be Chinese," the usual expression is "to be a Chinese person" (; "I am a Chinese person;" "I am Chinese"). This is sometimes called an equative verb. Another possibility is for the complement to be just a noun modifier (ending in ), the noun being omitted: Before the Han Dynasty, the character 是 served as a demonstrative pronoun meaning "this." (This usage survives in some idioms and wikiquote:Chinese proverbs, proverbs.) Some linguists believe that 是 developed into a copula because it often appeared, as a repetitive subject, after the subject of a sentence (in classical Chinese we can say, for example: "George W. Bush, ''this'' president of the United States" meaning "George W. Bush ''is'' the president of the United States). The character 是 appears to be formed as a Chinese character classification, compound of characters with the meanings of "early" and "straight." Another use of 是 in modern Chinese is in combination with the modifier 的 ''de'' to mean "yes" or to show agreement. For example:Question: 你的汽车是不是红色的? ''nǐ de qìchē shì bú shì hóngsè de?'' "Is your car red or not?"

Response: 是的 ''shì de'' "Is," meaning "Yes," or 不是 ''bú shì'' "Not is," meaning "No."(A more common way of showing that the person asking the question is correct is by simply saying "right" or "correct," 对 ''duì''; the corresponding negative answer is 不对 ''bú duì'', "not right.") Yet another use of 是 is in the ''shì...(de)'' construction, which is used to emphasize a particular element of the sentence; see . In Hokkien 是 ''sī'' acts as the copula, and 是 is the equivalent in Wu Chinese. Cantonese uses 係 () instead of 是; similarly, Hakka language, Hakka uses 係 ''he55''.

Siouan languages

In Siouan languages like Lakota language, Lakota, in principle almost all words—according to their structure—are verbs. So not only (transitive, intransitive and so-called "stative") verbs but even nouns often behave like verbs and do not need to have copulas. For example, the word ''wičháša'' refers to a man, and the verb "to-be-a-man" is expressed as ''wimáčhaša/winíčhaša/wičháša'' (I am/you are/he is a man). Yet there also is a copula ''héčha'' (to be a ...) that in most cases is used: ''wičháša hemáčha/heníčha/héčha'' (I am/you are/he is a man). In order to express the statement "I am a doctor of profession," one has to say ''pezuta wičháša hemáčha''. But, in order to express that that person is THE doctor (say, that had been phoned to help), one must use another copula ''iyé'' (to be the one): ''pežúta wičháša (kiŋ) miyé yeló'' (medicine-man DEF ART I-am-the-one MALE ASSERT). In order to refer to space (e.g., Robert is in the house), various verbs are used, e.g., ''yaŋkÁ'' (lit., to sit) for humans, or ''háŋ/hé'' (to stand upright) for inanimate objects of a certain shape. "Robert is in the house" could be translated as ''Robert thimáhel yaŋké (yeló)'', whereas "There's one restaurant next to the gas station" translates as ''Owótethipi wígli-oínažiŋ kiŋ hél isákhib waŋ hé''.Constructed languages

The constructed language Lojban has two words that act similar to a copula in natural languages. The clause ''me ... me'u'' turns whatever follows it into a predicate that means to be (among) what it follows. For example, ''me la .bob. (me'u)'' means "to be Bob," and ''me le ci mensi (me'u)'' means "to be one of the three sisters." Another one is ''du'', which is itself a predicate that means all its arguments are the same thing (equal). One word which is often confused for a copula in Lojban, but isn't one, is ''cu''. It merely indicates that the word which follows is the main predicate of the sentence. For example, ''lo pendo be mi cu zgipre'' means "my friend is a musician," but the word ''cu'' does not correspond to English ''is''; instead, the word ''zgipre'', which is a predicate, corresponds to the entire phrase "is a musician". The word ''cu'' is used to prevent ''lo pendo be mi zgipre'', which would mean "the friend-of-me type of musician".See also

* Indo-European copula * Nominal sentence * Stative verb * Subject complement * Zero copulaCitations

General references

* * * (See "copular sentences" and "existential sentences and expletive ''there''" in Volume II.) * * * Moro, A. (1997''The Raising of Predicates''

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England. * * Tüting, A. W. (December 2003).

Essay on Lakota syntax

'. . *

Further reading

* *External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Copula (Linguistics) Parts of speech Verb types