West Smithfield on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Smithfield, properly known as West Smithfield, is a district located in

Smithfield, properly known as West Smithfield, is a district located in

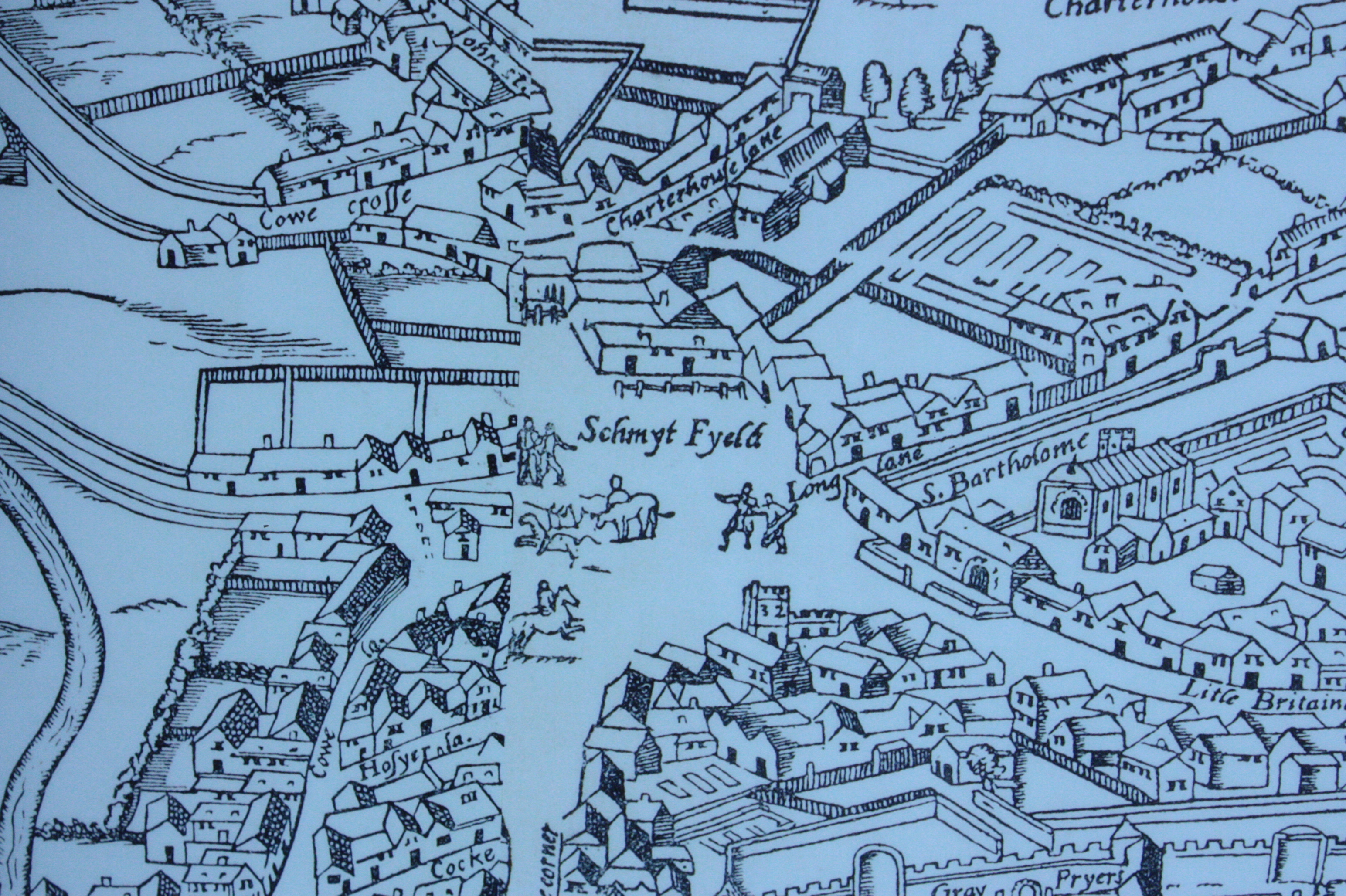

In the Middle Ages, it was a broad grassy area known as ''Smooth Field'', located beyond

In the Middle Ages, it was a broad grassy area known as ''Smooth Field'', located beyond

''The Records of St. Bartholomew's Priory ndSt. Bartholomew the Great, West Smithfield:'' volume 2 (1921), pp. 199–212. Retrieved 10 April 2009 An additional annual celebration, the In 1855, however, the City authorities closed Bartholomew Fair as they considered it to have degenerated into a magnet for debauchery and public disorder.

In 1348, Walter de Manny rented of land at ''Spital Croft'', north of Long Lane, from the

In 1855, however, the City authorities closed Bartholomew Fair as they considered it to have degenerated into a magnet for debauchery and public disorder.

In 1348, Walter de Manny rented of land at ''Spital Croft'', north of Long Lane, from the

''A History of the County of Middlesex:'' Volume 1: ''Physique, Archaeology, Domesday, Ecclesiastical Organization, The Jews, Religious Houses, Education of Working Classes to 1870, Private Education from Sixteenth Century'' (1969), pp. 159–169. accessed: 10 April 2009 Nearby and to the north of this demesne, the

''Old and New London'': Volume 2 (1878), pp. 359–363 accessed: 9 April 2009 The King Henry VIII Gate, which opens onto West Smithfield, was completed in 1702 and remains the hospital's main entrance. The Priory's principal church, St Bartholomew-the-Great, was reconfigured after the dissolution of the monasteries, losing the western third of its

Along with

Along with

In 1843, the ''Farmer's Magazine'' published a petition signed by bankers, salesmen, butchers,

In 1843, the ''Farmer's Magazine'' published a petition signed by bankers, salesmen, butchers,

The present Smithfield

The present Smithfield

Smithfield is the City of London's only major wholesale market (

Smithfield is the City of London's only major wholesale market (

Since 2005, the ''General Market'' (1883) and the adjacent ''Fish Market'' and ''Red House'' buildings (1898), part of the Victorian complex of the Smithfield Market, have been facing a threat of demolition. The

Since 2005, the ''General Market'' (1883) and the adjacent ''Fish Market'' and ''Red House'' buildings (1898), part of the Victorian complex of the Smithfield Market, have been facing a threat of demolition. The

File:Smithfield-meatmarket-large.jpg, The ''Central Market'' and ''Grand Avenue'' from the south

File:Grand Avenue Smithfield market.jpg, The entrance of the ''Grand Avenue'' from the south

File:Inside Smithfield market II, EC1.jpg, Inside the '' Poultry Market''

File:Market interior.jpg, Market interior

File:Smithfield Meat Market abandoned 1.jpg, The ''General Market'' (now abandoned)

File:Smithfield Meat Market abandoned 3.jpg, Inside the ''General Market'' (now abandoned)

File:East Poultry Avenue Smithfield market.jpg, East Poultry Avenue

File:Butchers' Hall (London).jpg, Butchers' Hall

File:St Bartholomew the Great, West Smithfield, London EC1 - Cloisters - geograph.org.uk - 1142485.jpg, St Bartholomew the Great Priory Church's cloisters and Barts Hospital

File:St Bartholomew the Less, St Bartholomews Hospital, West Smithfield, London EC1 - geograph.org.uk - 1140929.jpg, St Bartholomew the Less & Barts Hospital

File:St John's Gate 2007 5.jpg, St John's Gate

File:CharterhouseEC1.jpg, Charterhouse Square

File:Port of london com.jpg, The ''

Smithfield Market page

on the City of London website

literary quotations about Smithfield.

Smithfield Market in pictures

A portfolio of black-and-white photos featuring the market and the people who worked there in the earlier 1990s. * {{Good article Areas of London Districts of the City of London Execution sites in England London crime history

Central London

Central London is the innermost part of London, in England, spanning several boroughs. Over time, a number of definitions have been used to define the scope of Central London for statistics, urban planning and local government. Its characteris ...

, part of Farringdon Without

__NOTOC__

Farringdon Without is the most westerly Ward of the City of London, its suffix ''Without'' reflects its origin as lying beyond the City's former defensive walls. It was first established in 1394 to administer the suburbs west of Ludg ...

, the most westerly ward of the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London f ...

, England.

Smithfield is home to a number of City institutions, such as St Bartholomew's Hospital

St Bartholomew's Hospital, commonly known as Barts, is a teaching hospital located in the City of London. It was founded in 1123 and is currently run by Barts Health NHS Trust.

History

Early history

Barts was founded in 1123 by Rahere (die ...

and livery halls, including those of the Butchers' and Haberdashers' Companies. The area is best known for the Smithfield meat market

A meat market is, traditionally, a marketplace where meat is sold, often by a butcher. It is a specialized wet market. The term is sometimes used to refer to a meat retail store or butcher's shop, in particular in North America. During the mid ...

, which dates from the 10th century, has been in continuous operation since medieval times

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

, and is now London's only remaining wholesale

Wholesaling or distributing is the sale of goods or merchandise to retailers; to industrial, commercial, institutional or other professional business users; or to other wholesalers (wholesale businesses) and related subordinated services. I ...

market

Market is a term used to describe concepts such as:

*Market (economics), system in which parties engage in transactions according to supply and demand

*Market economy

*Marketplace, a physical marketplace or public market

Geography

*Märket, an ...

. Smithfield's principal street is called ''West Smithfield'', and the area also contains London's oldest surviving church, St Bartholomew-the-Great

The Priory Church of St Bartholomew the Great, sometimes abbreviated to Great St Bart's, is a medieval church in the Church of England's Diocese of London located in Smithfield within the City of London. The building was founded as an Augusti ...

, founded in AD 1123.

The area has borne witness to many executions of heretics and political rebels over the centuries, as well as Scottish knight Sir William Wallace

Sir William Wallace ( gd, Uilleam Uallas, ; Norman French: ; 23 August 1305) was a Scottish knight who became one of the main leaders during the First War of Scottish Independence.

Along with Andrew Moray, Wallace defeated an English army a ...

, and Wat Tyler, leader of the Peasants' Revolt

The Peasants' Revolt, also named Wat Tyler's Rebellion or the Great Rising, was a major uprising across large parts of England in 1381. The revolt had various causes, including the socio-economic and political tensions generated by the Blac ...

, among many other religious reformers and dissenters.

Smithfield Market, a Grade II listed

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern I ...

- covered market building, was designed by Victorian architect Sir Horace Jones

Sir Horace Jones (20 May 1819 – 21 May 1887) was an English architect particularly noted for his work as architect and surveyor to the City of London from 1864 until his death. He served as president of the Royal Institute of British Architec ...

in the second half of the 19th century, and is the dominant architectural feature of the area. Some of its original market premises fell into disuse in the late 20th century and faced the prospect of demolition. The Corporation of London

The City of London Corporation, officially and legally the Mayor and Commonalty and Citizens of the City of London, is the municipal governing body of the City of London, the historic centre of London and the location of much of the United Ki ...

's public enquiry in 2012 drew widespread support for an urban regeneration plan intent upon preserving Smithfield's historical identity.

Smithfield area

London Wall

The London Wall was a defensive wall first built by the Romans around the strategically important port town of Londinium in AD 200, and is now the name of a modern street in the City of London. It has origins as an initial mound wall and ...

stretching to the eastern bank of the River Fleet

The River Fleet is the largest of London's subterranean rivers, all of which today contain foul water for treatment. Its headwaters are two streams on Hampstead Heath, each of which was dammed into a series of ponds—the Hampstead Ponds an ...

. Given its ease of access to grazing

In agriculture, grazing is a method of animal husbandry whereby domestic livestock are allowed outdoors to roam around and consume wild vegetations in order to convert the otherwise indigestible (by human gut) cellulose within grass and ot ...

and water

Water (chemical formula ) is an inorganic, transparent, tasteless, odorless, and nearly colorless chemical substance, which is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living organisms (in which it acts as ...

, Smithfield established itself as London's livestock

Livestock are the domesticated animals raised in an agricultural setting to provide labor and produce diversified products for consumption such as meat, eggs, milk, fur, leather, and wool. The term is sometimes used to refer solely to ani ...

market

Market is a term used to describe concepts such as:

*Market (economics), system in which parties engage in transactions according to supply and demand

*Market economy

*Marketplace, a physical marketplace or public market

Geography

*Märket, an ...

, remaining so for almost 1,000 years. Many local toponyms

Toponymy, toponymics, or toponomastics is the study of '' toponyms'' (proper names of places, also known as place names and geographic names), including their origins, meanings, usage and types. Toponym is the general term for a proper name of ...

are associated with the livestock trade: while some street names (such as "Cow Cross Street" and "Cock Lane

Cock Lane is a small street in Smithfield in the City of London, leading from Giltspur Street in the east to Snow Hill in the west.

In the medieval period, it was known as ''Cokkes Lane'' and was the site of legal brothels. 25 Cock Lane is t ...

") remain in use, many more (such as "Chick Lane", "Duck Lane", "Cow Lane", "Pheasant Court", "Goose Alley") have disappeared from the map

A map is a symbolic depiction emphasizing relationships between elements of some space, such as objects, regions, or themes.

Many maps are static, fixed to paper or some other durable medium, while others are dynamic or interactive. Although ...

after the major redevelopment of the area in the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwa ...

.

Religious history

In 1123, the area nearAldersgate

Aldersgate is a Ward of the City of London, named after one of the northern gates in the London Wall which once enclosed the City.

The Ward of Aldersgate is traditionally divided into Aldersgate Within and Aldersgate Without, the suffix den ...

was granted by King Henry I for the foundation of St Bartholomew's Priory at the request of Prior Rahere, in thanks for his being nursed back to good health. The Priory exercised its right to enclose land between the vicinity of the boundary with Aldersgate Without (to the east), Long Lane (to the north) and modern-day Newgate Street (to the south), erecting its main western gate which opened onto Smithfield, and a postern

A postern is a secondary door or gate in a fortification such as a city wall or castle curtain wall. Posterns were often located in a concealed location which allowed the occupants to come and go inconspicuously. In the event of a siege, a postern ...

on Long Lane. By facing the open space of Smithfield and by having 'its back to' the buildings lining Aldersgate Street

Aldersgate is a Ward of the City of London, named after one of the northern gates in the London Wall which once enclosed the City.

The Ward of Aldersgate is traditionally divided into Aldersgate Within and Aldersgate Without, the suffix den ...

, the Priory site has left a continuing legacy of limited connectivity between the Smithfield area and Aldersgate Street.

The Priory thereafter held the manorial rights to hold weekly fair

A fair (archaic: faire or fayre) is a gathering of people for a variety of entertainment or commercial activities. Fairs are typically temporary with scheduled times lasting from an afternoon to several weeks.

Types

Variations of fairs incl ...

s, which initially took place in its outer court on the site of present-day Cloth Fair, leading to "Fair Gate".''The parish: Bounds, gates and watchmen''''The Records of St. Bartholomew's Priory ndSt. Bartholomew the Great, West Smithfield:'' volume 2 (1921), pp. 199–212. Retrieved 10 April 2009 An additional annual celebration, the

Bartholomew Fair

The Bartholomew Fair was one of London's pre-eminent summer charter fairs. A charter for the fair was granted to Rahere by Henry I to fund the Priory of St Bartholomew; and from 1133 to 1855 it took place each year on 24 August within the preci ...

, was established in 1133 by the Augustinian friars. Over time, this became one of London's pre-eminent summer fairs, opening each year on 24 August. A trading event for cloth

Textile is an umbrella term that includes various fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, filaments, threads, different fabric types, etc. At first, the word "textiles" only referred to woven fabrics. However, weaving is not the ...

and other goods as well as being a pleasure forum, the four-day festival drew crowds from all strata

In geology and related fields, a stratum ( : strata) is a layer of rock or sediment characterized by certain lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separated by visible surfaces known as e ...

of English society.

In 1855, however, the City authorities closed Bartholomew Fair as they considered it to have degenerated into a magnet for debauchery and public disorder.

In 1348, Walter de Manny rented of land at ''Spital Croft'', north of Long Lane, from the

In 1855, however, the City authorities closed Bartholomew Fair as they considered it to have degenerated into a magnet for debauchery and public disorder.

In 1348, Walter de Manny rented of land at ''Spital Croft'', north of Long Lane, from the Master

Master or masters may refer to:

Ranks or titles

* Ascended master, a term used in the Theosophical religious tradition to refer to spiritually enlightened beings who in past incarnations were ordinary humans

*Grandmaster (chess), National Master ...

and Brethren of St Bartholomew's Hospital, for a graveyard and plague pit for victims of the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

. A chapel and hermitage were constructed, renamed ''New Church Haw''; but in 1371, this land was granted for the foundation of the Charterhouse, originally a Carthusian

The Carthusians, also known as the Order of Carthusians ( la, Ordo Cartusiensis), are a Latin enclosed religious order of the Catholic Church. The order was founded by Bruno of Cologne in 1084 and includes both monks and nuns. The order has i ...

monastery

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer whic ...

.''Religious Houses: House of Carthusian monks''''A History of the County of Middlesex:'' Volume 1: ''Physique, Archaeology, Domesday, Ecclesiastical Organization, The Jews, Religious Houses, Education of Working Classes to 1870, Private Education from Sixteenth Century'' (1969), pp. 159–169. accessed: 10 April 2009 Nearby and to the north of this demesne, the

Knights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic military order. It was headq ...

established a Commandery

In the Middle Ages, a commandery (rarely commandry) was the smallest administrative division of the European landed properties of a military order. It was also the name of the house where the knights of the commandery lived.Anthony Luttrell and ...

at Clerkenwell, dedicated to St John in the mid-12th century. In 1194 they received a Charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the re ...

from King Richard I

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199) was King of England from 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ruled as Duke of Normandy, Aquitaine and Gascony, Lord of Cyprus, and Count of Poitiers, Anjou, Maine, and Nantes, and was ove ...

granting the Order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of ...

formal privileges. Later Augustinian canoness

Canoness is a member of a religious community of women living a simple life. Many communities observe the monastic Rule of St. Augustine. The name corresponds to the male equivalent, a canon. The origin and Rule are common to both. As with the ...

es established the Priory of St Mary, north of the Knights of St John

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic military order. It was headqu ...

property.

By the end of the 14th century, these religious houses were regarded by City traders as interlopers – occupying what had previously been public open space near one of the City gate

A city gate is a gate which is, or was, set within a city wall. It is a type of fortified gateway.

Uses

City gates were traditionally built to provide a point of controlled access to and departure from a walled city for people, vehicles, go ...

s. On numerous occasions vandals damaged the Charterhouse, eventually demolishing its buildings. By 1405, a stout wall was built to protect the property and maintain the privacy of the Order, particularly its church where men and women alike came to worship.

The religious houses were dissolved in the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

, and their lands broken up. The Priory Church of St John remains, as does St John's Gate. John Houghton John Houghton may refer to:

Politicians

* John Houghton (fl.1393), MP for Leicester (UK Parliament constituency)

* John Houghton (died 1583) (before 1522–1583), MP for Stamford (UK Parliament constituency)

* John Houghton (Manx politician)

* J ...

(later canonized by Pope Paul VI as ''St John Houghton''), The prior of Charterhouse went to Thomas Cromwell

Thomas Cromwell (; 1485 – 28 July 1540), briefly Earl of Essex, was an English lawyer and statesman who served as chief minister to King Henry VIII from 1534 to 1540, when he was beheaded on orders of the king, who later blamed false char ...

, accompanied by two other local priors, seeking an oath of supremacy

The Oath of Supremacy required any person taking public or church office in England to swear allegiance to the monarch as Supreme Governor of the Church of England. Failure to do so was to be treated as treasonable. The Oath of Supremacy was or ...

that would be acceptable to their communities

A community is a social unit (a group of living things) with commonality such as place, norms, religion, values, customs, or identity. Communities may share a sense of place situated in a given geographical area (e.g. a country, village, to ...

. Instead they were imprisoned in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

, and on 4 May 1535, they were taken to Tyburn

Tyburn was a Manorialism, manor (estate) in the county of Middlesex, one of two which were served by the parish of Marylebone.

The parish, probably therefore also the manor, was bounded by Roman roads to the west (modern Edgware Road) and sout ...

and hanged – becoming the first Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

s of the Reformation. On 29 May, the remaining twenty monks and eighteen lay brothers were forced to swear the oath of allegiance to King Henry VIII; the ten who refused were taken to Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey Street just inside the City of London, England, originally at the site of Newgate, a gate in the Roman London Wall. Built in the 12th century and demolished in 1904, t ...

and left to starve.

With the monks expelled, Charterhouse was requisitioned and remained as a private dwelling until its reestablishment by Thomas Sutton

Thomas Sutton (1532 – 12 December 1611) was an English civil servant and businessman, born in Knaith, Lincolnshire. He is remembered as the founder of the London Charterhouse and of Charterhouse School.

Life

Sutton was the son of an official ...

in 1611 as a charitable foundation; it was the basis of the school named Charterhouse

Charterhouse may refer to:

* Charterhouse (monastery), of the Carthusian religious order

Charterhouse may also refer to:

Places

* The Charterhouse, Coventry, a former monastery

* Charterhouse School, an English public school in Surrey

Londo ...

and almshouse

An almshouse (also known as a bede-house, poorhouse, or hospital) was charitable housing provided to people in a particular community, especially during the medieval era. They were often targeted at the poor of a locality, at those from certain ...

s known as ''Sutton's Hospital in Charterhouse'' on its former site. The school was relocated to Godalming

Godalming is a market town and civil parish in southwest Surrey, England, around southwest of central London. It is in the Borough of Waverley, at the confluence of the Rivers Wey and Ock. The civil parish covers and includes the settlement ...

in 1872. Until 1899 Charterhouse was extra-parochial

In England and Wales, an extra-parochial area, extra-parochial place or extra-parochial district was a geographically defined area considered to be outside any ecclesiastical or civil parish. Anomalies in the parochial system meant they had no ...

; that year it became a civil parish

In England, a civil parish is a type of administrative parish used for local government. It is a territorial designation which is the lowest tier of local government below districts and counties, or their combined form, the unitary authorit ...

incorporated in the Metropolitan Borough of Finsbury

The Metropolitan Borough of Finsbury was a Metropolitan borough within the County of London from 1900 to 1965, when it was amalgamated with the Metropolitan Borough of Islington to form the London Borough of Islington.

Formation and boundaries

...

. Some of the property was damaged during The Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

, but it remains largely intact. Part of the site is now occupied by Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry

, mottoeng = Temper the bitter things in life with a smile

, parent = Queen Mary University of London

, president = Lord Mayor of London

, head_label = Warden

, head = Mark Caulfield

, students = 3,410

, undergrad = 2,235 ...

.

From its inception, the Priory of St Bartholomew treated the sick. After the Reformation it was left with neither income nor monastic occupants but, following a petition by the City Corporation, Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

refounded it in December 1546, as the "House of the Poore in West Smithfield in the suburbs of the City of London of Henry VIII's Foundation". Letters Patent

Letters patent ( la, litterae patentes) ( always in the plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, president or other head of state, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, tit ...

were presented to the City

A city is a human settlement of notable size.Goodall, B. (1987) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography''. London: Penguin.Kuper, A. and Kuper, J., eds (1996) ''The Social Science Encyclopedia''. 2nd edition. London: Routledge. It can be def ...

, granting property and income to the new foundation the following month. King Henry VIII's sergeant-surgeon, Thomas Vicary

Thomas Vicary (c. 1490—1561) was an early English physician, surgeon and anatomist.

Vicary was born in Kent, in about 1490. He was described as "but a meane practiser in Maidstone … that had gained his knowledge by experience, until the Ki ...

, was appointed as the hospital

A hospital is a health care institution providing patient treatment with specialized health science and auxiliary healthcare staff and medical equipment. The best-known type of hospital is the general hospital, which typically has an emergen ...

's first superintendent

Superintendent may refer to:

*Superintendent (police), Superintendent of Police (SP), or Senior Superintendent of Police (SSP), a police rank

*Prison warden or Superintendent, a prison administrator

*Superintendent (ecclesiastical), a church exec ...

.''St Bartholomew's Hospital''''Old and New London'': Volume 2 (1878), pp. 359–363 accessed: 9 April 2009 The King Henry VIII Gate, which opens onto West Smithfield, was completed in 1702 and remains the hospital's main entrance. The Priory's principal church, St Bartholomew-the-Great, was reconfigured after the dissolution of the monasteries, losing the western third of its

nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-typ ...

. Reformed as an Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

parish church

A parish church (or parochial church) in Christianity is the church which acts as the religious centre of a parish. In many parts of the world, especially in rural areas, the parish church may play a significant role in community activities, ...

, its parish boundaries were limited to the site of the ancient priory and a small tract of land between the church and Long Lane. The parish of St Bartholomew the Great was designated as a Liberty

Liberty is the ability to do as one pleases, or a right or immunity enjoyed by prescription or by grant (i.e. privilege). It is a synonym for the word freedom.

In modern politics, liberty is understood as the state of being free within society fr ...

, responsible for the upkeep and security of its fabric and the land within its boundaries. With the advent of street lighting, mains water, and sewerage during the Victorian era, maintenance of such an ancient parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one or ...

with so few parishioners became increasingly uneconomical after the Industrial Revolution. In 1910, it agreed to be incorporated by the Corporation of London

The City of London Corporation, officially and legally the Mayor and Commonalty and Citizens of the City of London, is the municipal governing body of the City of London, the historic centre of London and the location of much of the United Ki ...

which guaranteed financial support and security. Great St Barts' present parish boundary includes just 10 feet (3.048 m) of Smithfield – possibly delineating a former right of way

Right of way is the legal right, established by grant from a landowner or long usage (i.e. by prescription), to pass along a specific route through property belonging to another.

A similar ''right of access'' also exists on land held by a gov ...

.

After the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

, a separate parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one or ...

likewise dedicated to St Bartholomew

Bartholomew (Aramaic: ; grc, Βαρθολομαῖος, translit=Bartholomaîos; la, Bartholomaeus; arm, Բարթողիմէոս; cop, ⲃⲁⲣⲑⲟⲗⲟⲙⲉⲟⲥ; he, בר-תולמי, translit=bar-Tôlmay; ar, بَرثُولَماو� ...

was granted in favour of St Bartholomew's Hospital

St Bartholomew's Hospital, commonly known as Barts, is a teaching hospital located in the City of London. It was founded in 1123 and is currently run by Barts Health NHS Trust.

History

Early history

Barts was founded in 1123 by Rahere (die ...

; named St Bartholomew-the-Less, it remained under the hospital's patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

, unique in the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

, until 1948, when the hospital was nationalized in the National Health Service

The National Health Service (NHS) is the umbrella term for the publicly funded healthcare systems of the United Kingdom (UK). Since 1948, they have been funded out of general taxation. There are three systems which are referred to using the " ...

. The church benefice

A benefice () or living is a reward received in exchange for services rendered and as a retainer for future services. The Roman Empire used the Latin term as a benefit to an individual from the Empire for services rendered. Its use was adopted by ...

has since been joined again with its ancient partner, the Priory Church of St Bartholomew the Great.

Following the diminished influence of the ancient Priory, predecessor of the two parishes of St Bartholomew, disputes began to arise over rights to tithes and taxes payable by lay residents who claimed allegiance with the nearby and anciently associated parish of St Botolph Aldersgate

St Botolph without Aldersgate (also known as St Botolph's, Aldersgate) is a Church of England church in London dedicated to St Botolph. It was built just outside Aldersgate; one of the gates on London's wall in the City of London.

The chur ...

– an unintended consequence and legacy of King Henry VIII's religious reforms.

Smithfield and its Market, situated mostly in the parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one or ...

of St Sepulchre, was founded in 1137, and was endowed by Prior Rahere, who also founded St Barts. The ancient parish of St Sepulchre extended north to Turnmill Street

Turnmill Street is a street in Clerkenwell, London. It runs north–south from Clerkenwell Road in the north, to Cowcross Street in the south. One of the oldest streets in London, it has been variously known as Turnmill and Turnbull Street ov ...

, to St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglicanism, Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London ...

and Ludgate Hill

Ludgate Hill is a street and surrounding area, on a small hill in the City of London. The street passes through the former site of Ludgate, a city gate that was demolished – along with a gaol attached to it – in 1760.

The area include ...

in the south, and along the east bank

A bank is a financial institution that accepts Deposit account, deposits from the public and creates a demand deposit while simultaneously making loans. Lending activities can be directly performed by the bank or indirectly through capital m ...

of the Fleet

Fleet may refer to:

Vehicles

*Fishing fleet

*Naval fleet

*Fleet vehicles, a pool of motor vehicles

*Fleet Aircraft, the aircraft manufacturing company

Places

Canada

* Fleet, Alberta, Canada, a hamlet

England

* The Fleet Lagoon, at Chesil Beach ...

(now the route of Farringdon Street

Farringdon Road is a road in Clerkenwell, London.

Route

Farringdon Road is part of the A201 route connecting King's Cross to Elephant and Castle. It goes southeast from King's Cross, crossing Rosebery Avenue, then turns south, crossing Cl ...

). St Sepulchre's Tower contains the twelve "bells of Old Bailey", referred to in the nursery rhyme " Oranges and Lemons". Traditionally, the Great Bell was rung to announce the execution of a prisoner

A prisoner (also known as an inmate or detainee) is a person who is deprived of liberty against their will. This can be by confinement, captivity, or forcible restraint. The term applies particularly to serving a prison sentence in a prison. ...

at Newgate

Newgate was one of the historic seven gates of the London Wall around the City of London and one of the six which date back to Roman times. Newgate lay on the west side of the wall and the road issuing from it headed over the River Fleet to Mid ...

.

Civil history

As a large open space close to the City, Smithfield was a popular place for public gatherings. In 1374Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

held a seven-day tournament

A tournament is a competition involving at least three competitors, all participating in a sport or game. More specifically, the term may be used in either of two overlapping senses:

# One or more competitions held at a single venue and concentr ...

at Smithfield, for the amusement of his beloved Alice Perrers

Alice Perrers, also known as Alice de Windsor (circa 1348 –1400) was an English royal mistress, lover of Edward III, King of England. As a result of his patronage, she became the wealthiest and most influential woman in the country. She ...

. Possibly the most famous medieval tournament

A tournament, or tourney (from Old French ''torneiement'', ''tornei''), was a chivalrous competition or mock fight in the Middle Ages and Renaissance (12th to 16th centuries), and is one type of hastilude. Tournaments included melee and han ...

at Smithfield was that commanded in 1390 by Richard II

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward the Black Prince, Prince of Wales, and Joan, Countess of Kent. Richard's father ...

. Jean Froissart

Jean Froissart (Old and Middle French: ''Jehan'', – ) (also John Froissart) was a French-speaking medieval author and court historian from the Low Countries who wrote several works, including ''Chronicles'' and ''Meliador'', a long Arthurian ...

, in his fourth book of Chronicles

Chronicles may refer to:

* ''Books of Chronicles'', in the Bible

* Chronicle, chronological histories

* ''The Chronicles of Narnia'', a novel series by C. S. Lewis

* ''Holinshed's Chronicles'', the collected works of Raphael Holinshed

* '' The Idh ...

, reported that sixty knights would come to London to tilt for two days, "accompanied by sixty noble ladies, richly ornamented and dressed". The tournament was proclaimed by herald

A herald, or a herald of arms, is an officer of arms, ranking between pursuivant and king of arms. The title is commonly applied more broadly to all officers of arms.

Heralds were originally messengers sent by monarchs or noblemen to ...

s throughout England, Scotland, Hainault, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

, Flanders and France, so as to rival the jousts given by Charles of France at Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

a few years earlier, upon the arrival of his consort Isabel of Bavaria. Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for '' The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He w ...

supervised preparations for the tournament as a clerk to the King.

Along with

Along with Tyburn

Tyburn was a Manorialism, manor (estate) in the county of Middlesex, one of two which were served by the parish of Marylebone.

The parish, probably therefore also the manor, was bounded by Roman roads to the west (modern Edgware Road) and sout ...

, Smithfield was for centuries the main site for the public execution

A public execution is a form of capital punishment which "members of the general public may voluntarily attend." This definition excludes the presence of only a small number of witnesses called upon to assure executive accountability. The purpose ...

of heretic

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important relig ...

s and dissident

A dissident is a person who actively challenges an established political or religious system, doctrine, belief, policy, or institution. In a religious context, the word has been used since the 18th century, and in the political sense since the 20th ...

s in London. The Scottish nobleman Sir William Wallace

Sir William Wallace ( gd, Uilleam Uallas, ; Norman French: ; 23 August 1305) was a Scottish knight who became one of the main leaders during the First War of Scottish Independence.

Along with Andrew Moray, Wallace defeated an English army a ...

was executed in 1305 at West Smithfield. The market was the meeting place prior to the Peasants' Revolt

The Peasants' Revolt, also named Wat Tyler's Rebellion or the Great Rising, was a major uprising across large parts of England in 1381. The revolt had various causes, including the socio-economic and political tensions generated by the Blac ...

and where the Revolt's leader, Wat Tyler, was slain by Sir William Walworth, Lord Mayor of London

The Lord Mayor of London is the mayor of the City of London and the leader of the City of London Corporation. Within the City, the Lord Mayor is accorded precedence over all individuals except the sovereign and retains various traditional pow ...

on 15 June 1381.

Religious dissenters (Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

s as well as other Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

denominations such as Anabaptist

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek : 're-' and 'baptism', german: Täufer, earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. ...

s) were sentenced to death

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

in this area during the Crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, partic ...

's changing course of religious orientation started by King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

. About fifty Protestants and religious reformers, known as the Marian martyrs

Protestants were executed in England under heresy laws during the reigns of Henry VIII (1509–1547) and Mary I (1553–1558). Radical Christians also were executed, though in much smaller numbers, during the reigns of Edward VI (1547–1553), ...

, were executed at Smithfield during the reign of Mary I

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, and as "Bloody Mary" by her Protestant opponents, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain from January 1556 until her death in 1558. She ...

.

G.K. Chesterton observed ironically:

On 17 November 1558, several Protestant heretics were saved by a royal herald's timely announcement that Queen Mary had died shortly before the wooden faggots were to be lit at the Smithfield Stake. Under English Law

English law is the common law legal system of England and Wales, comprising mainly criminal law and civil law, each branch having its own courts and procedures.

Principal elements of English law

Although the common law has, historically, b ...

death warrants were commanded by Sign Manual

The royal sign-manual is the signature of the sovereign, by the affixing of which the monarch expresses his or her pleasure either by order, commission, or warrant. A sign-manual warrant may be either an executive act (for example, an appointmen ...

(the personal signature of the Monarch

A monarch is a head of stateWebster's II New College DictionarMonarch Houghton Mifflin. Boston. 2001. p. 707. Life tenure, for life or until abdication, and therefore the head of state of a monarchy. A monarch may exercise the highest authority ...

), invariably upon ministerial recommendation, which if unexercised by the time of a Sovereign's death required renewed authority. In this case Queen Elizabeth

Queen Elizabeth, Queen Elisabeth or Elizabeth the Queen may refer to:

Queens regnant

* Elizabeth I (1533–1603; ), Queen of England and Ireland

* Elizabeth II (1926–2022; ), Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms

* Queen ...

did not approve the executions, thus freeing the Protestants. During the 16th century the Smithfield site was also the place of execution of swindler

A charlatan (also called a swindler or mountebank) is a person practicing quackery or a similar confidence trick in order to obtain money, power, fame, or other advantages through pretense or deception. Synonyms for ''charlatan'' include ''shy ...

s and coin forgers, who were boiled to death in oil.

By the 18th century the "Tyburn Tree" (near the present-day Marble Arch

The Marble Arch is a 19th-century white marble-faced triumphal arch in London, England. The structure was designed by John Nash in 1827 to be the state entrance to the cour d'honneur of Buckingham Palace; it stood near the site of what is toda ...

) became the main place for public executions in London. After 1785, executions were again moved, this time to the gates of Newgate prison, just to the south of Smithfield.

The Smithfield area emerged largely unscathed by the Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through central London from Sunday 2 September to Thursday 6 September 1666, gutting the medieval City of London inside the old Roman city wall, while also extending past th ...

in 1666, which was abated near the Fortune of War Tavern, at the junction of Giltspur Street

Giltspur Street is a street in Smithfield in the City of London, running north–south from the junction of Newgate Street, Holborn Viaduct and Old Bailey, up to West Smithfield, and it is bounded to the east by St Bartholomew's Hospital. I ...

and Cock Lane, where the statue

A statue is a free-standing sculpture in which the realistic, full-length figures of persons or animals are carved or cast in a durable material such as wood, metal or stone. Typical statues are life-sized or close to life-size; a sculpture t ...

of the Golden Boy of Pye Corner

The Golden Boy of Pye Corner is a small late-17th-century monument located on the corner of Giltspur Street and Cock Lane in Smithfield, central London. It marks the spot where the 1666 Great Fire of London was stopped, whereas the Monument in ...

is located. In the late 17th century several residents of Smithfield emigrated to North America, where they founded the town

A town is a human settlement. Towns are generally larger than villages and smaller than cities, though the criteria to distinguish between them vary considerably in different parts of the world.

Origin and use

The word "town" shares an o ...

of Smithfield, Rhode Island

Smithfield is a town that is located in Providence County, Rhode Island, United States. It includes the historic villages of Esmond, Georgiaville, Mountaindale, Hanton City, Stillwater and Greenville. The population was 22,118 at the 2020 cens ...

.

West Smithfield Bars

Until the 19th century the area included boundary markers known as the West Smithfield Bars (or more simply, Smithfield Bars).BHO https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp203-221 These marked the northern boundary of the City of London and were placed at a point approximating to where modernCharterhouse Street

Charterhouse Street is a street on the north side of Smithfield in the City of London. The road forms part of the City’s boundary with the neighbouring London Boroughs of Islington and Camden. It connects Charterhouse Square and Holborn Circ ...

meets St John Street, which was historically the first stretch of the Great North Road. The Bars were on the route of the former Fagswell Brook, a tributary of the Fleet, which marked the City's northern boundary in the area.

The Bars are first documented in 1170 and 1197, and were a site of public executions.

Today

Since the late 1990s, Smithfield and neighbouring Farringdon have developed a reputation for being a cultural hub for up-and-coming professionals, who enjoy its bars, restaurants and night clubs. Nightclubs such asFabric

Textile is an umbrella term that includes various fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, filaments, threads, different fabric types, etc. At first, the word "textiles" only referred to woven fabrics. However, weaving is not ...

and Turnmills

The Turnmills building was a warehouse originally on the corner of Turnmill Street and Clerkenwell Road in the London Borough of Islington. It became a bar in the 1980s, then a nightclub. The club closed in 2008 and the building was later demol ...

pioneered the area's reputation for trendy night life

Nightlife is a collective term for entertainment that is available and generally more popular from the late evening into the early hours of the morning. It includes pubs, bars, nightclubs, parties, live music, concerts, cabarets, theatre, ...

, attracting professionals from nearby Holborn

Holborn ( or ) is a district in central London, which covers the south-eastern part of the London Borough of Camden and a part ( St Andrew Holborn Below the Bars) of the Ward of Farringdon Without in the City of London.

The area has its ro ...

, Clerkenwell

Clerkenwell () is an area of central London, England.

Clerkenwell was an ancient parish from the mediaeval period onwards, and now forms the south-western part of the London Borough of Islington.

The well after which it was named was redis ...

and the City

A city is a human settlement of notable size.Goodall, B. (1987) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography''. London: Penguin.Kuper, A. and Kuper, J., eds (1996) ''The Social Science Encyclopedia''. 2nd edition. London: Routledge. It can be def ...

on weekdays. At weekends, the clubs and bars in the area, having late licences, draw people into the area from outside London too.

Smithfield has also become a venue for sporting events. Until 2002 Smithfield hosted the midnight start of the annual Miglia Quadrato Car Rally, but with the increased night club activity around Smithfield, the UHULMC (a motoring club) decided to move the event's start to Finsbury Circus

Finsbury Circus is a park in the Coleman Street Ward of the City of London, England. The 2 acre park is the largest public open space within the City's boundaries.

It is not to be confused with Finsbury Square, just north of the City, or Fi ...

. Since 2007, Smithfield has been the chosen site of an annual event dedicated to road bicycle racing

Road bicycle racing is the cycle sport discipline of road cycling, held primarily on paved roads. Road racing is the most popular professional form of bicycle racing, in terms of numbers of competitors, events and spectators. The two most common ...

known as the ''Smithfield Nocturne''.

Number 1, West Smithfield is head office of the Churches Conservation Trust

The Churches Conservation Trust is a registered charity whose purpose is to protect historic churches at risk in England. The charity cares for over 350 churches of architectural, cultural and historic significance, which have been transferred in ...

.

Market

Origins

Meat has been traded at Smithfield Market for more than 800 years, making it one of the oldestmarkets

Market is a term used to describe concepts such as:

*Market (economics), system in which parties engage in transactions according to supply and demand

*Market economy

*Marketplace, a physical marketplace or public market

Geography

*Märket, an ...

in London. A livestock

Livestock are the domesticated animals raised in an agricultural setting to provide labor and produce diversified products for consumption such as meat, eggs, milk, fur, leather, and wool. The term is sometimes used to refer solely to ani ...

market occupied the site as early as the 10th century.

In 1174 the site was described by William Fitzstephen

William Fitzstephen (also William fitz Stephen), (died c. 1191) was a cleric and administrator in the service of Thomas Becket. In the 1170s he wrote a long biography of Thomas Becket – the ''Vita Sancti Thomae'' (Life of St. Thomas).

Fitzsteph ...

as:

a smooth field where every Friday there is a celebrated rendezvous of fine horses to be traded, and in another quarter are placed vendibles of the peasant, swine with their deep flanks, and cows and oxen of immense bulk.Costs, customs and rules were meticulously laid down. For instance, for an ox, a cow or a dozen sheep one could get 1 penny. The livestock market expanded over the centuries to meet demand from the growing population of the City. In 1710, the

market

Market is a term used to describe concepts such as:

*Market (economics), system in which parties engage in transactions according to supply and demand

*Market economy

*Marketplace, a physical marketplace or public market

Geography

*Märket, an ...

was surrounded by a wooden fence containing the livestock within the market. Until the market's abolition, the Gate House at Cloth Fair ("Fair Gate") employed a chain

A chain is a serial assembly of connected pieces, called links, typically made of metal, with an overall character similar to that of a rope in that it is flexible and curved in compression but linear, rigid, and load-bearing in tension. ...

(''le cheyne'') on market days. Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, trader, journalist, pamphleteer and spy. He is most famous for his novel '' Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its ...

referred to the livestock market in 1726 as being "without question, the greatest in the world", and data available appear to corroborate his statement.

Between 1740 and 1750 the average yearly sales at Smithfield were reported to be around 74,000 cattle and 570,000 sheep. By the middle of the 19th century, in the course of a single year 220,000 head of cattle and 1,500,000 sheep would be "violently forced into an area of five acres, in the very heart of London, through its narrowest and most crowded thoroughfares". The volume of cattle driven daily to Smithfield started to raise major concerns.

The Great North Road traditionally began at Smithfield Market, with St John Street and Islington High Street forming the initial stages. Road mileages were taken from Hicks Hall

Hicks Hall, or Hickes' Hall, was a courthouse at the southern end of St John Street, Clerkenwell, London. It opened in 1612, and was closed and demolished in 1782. It was the first purpose-built sessions house for justices of the peace of the ...

, a short distance up St John Street, some 90 metres north of the ''West Smithfield Bars''. The site of the hall continued to be used as the starting point for mileages even after it was demolished soon after 1778. The road followed St John Street, and continued north, eventually leading to Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

. Using the former site of the hall as the starting point ended in 1829, with the establishment of the General Post Office

The General Post Office (GPO) was the state postal system and telecommunications carrier of the United Kingdom until 1969. Before the Acts of Union 1707, it was the postal system of the Kingdom of England, established by Charles II in 1660. ...

at St Martin's-le-Grand, which became the new starting point, with the route following Goswell Road before joining Islington High Street and then re-joining the historic route.

Local campaigning against the cattle market

In theVictorian period

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edward ...

, pamphlets started circulating in favour of the removal of the livestock market and its relocation outside of the City, due to its extremely poor hygienic conditions as well as the brutal treatment of the cattle. The conditions at the market in the first half of the 19th century were often described as a major threat to public health:

Of all the horrid abominations with which London has been cursed, there is not one that can come up to that disgusting place, West Smithfield Market, for cruelty, filth, effluvia, pestilence, impiety, horrid language, danger, disgusting and shuddering sights, and every obnoxious item that can be imagined; and this abomination is suffered to continue year after year, from generation to generation, in the very heart of the most Christian and most polished city in the world.

In 1843, the ''Farmer's Magazine'' published a petition signed by bankers, salesmen, butchers,

In 1843, the ''Farmer's Magazine'' published a petition signed by bankers, salesmen, butchers, aldermen

An alderman is a member of a municipal assembly or council in many jurisdictions founded upon English law. The term may be titular, denoting a high-ranking member of a borough or county council, a council member chosen by the elected members the ...

and City residents against further expansion of the meat market, arguing that livestock markets had been systematically banned since the Middle Ages in other areas of London:

Our ancestors appear, in sanitary matters, to have been wiser than we are. There exists, amongst the Rolls of Parliament of the year 1380, a petition from the citizens of London, praying – that, for the sake of the public health, meat should not be slaughtered nearer than " Knyghtsbrigg", under penalty, not only of forfeiting such animals as might be killed in the "butcherie", but of a year's imprisonment. The prayer of this petition was granted, audits penalties were enforced during several reigns.

Thomas Hood

Thomas Hood (23 May 1799 – 3 May 1845) was an English poet, author and humorist, best known for poems such as " The Bridge of Sighs" and " The Song of the Shirt". Hood wrote regularly for ''The London Magazine'', '' Athenaeum'', and ''Punch' ...

wrote in 1830 an ''Ode to the Advocates for the Removal of Smithfield Market'', applauding those "philanthropic men" who aim at removing to a distance the "vile Zoology" of the market and "routing that great nest of Hornithology". Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian er ...

criticised locating a livestock market in the heart of the capital

Capital may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** List of national capital cities

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter Economics and social sciences

* Capital (economics), the durable produced goods used fo ...

in his 1851 essay '' A Monument of French Folly'' drawing comparisons with the French market at Poissy

Poissy () is a commune in the Yvelines department in the Île-de-France region in north-central France. It is located in the western suburbs of Paris, from the centre of Paris. Inhabitants are called ''Pisciacais'' in French.

Poissy is one ...

outside Paris:

Of a great Institution like Smithfield,Anhe French He or HE may refer to: Language * He (pronoun), an English pronoun * He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ * He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets * He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...are unable to form the least conception. A Beast Market in the heart of Paris would be regarded an impossible nuisance. Nor have they any notion of slaughter-houses in the midst of acity A city is a human settlement of notable size.Goodall, B. (1987) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography''. London: Penguin.Kuper, A. and Kuper, J., eds (1996) ''The Social Science Encyclopedia''. 2nd edition. London: Routledge. It can be def .... One of these benighted frog-eaters would scarcely understand your meaning, if you told him of the existence of such a British bulwark.

Act of Parliament

Acts of Parliament, sometimes referred to as primary legislation, are texts of law passed by the legislative body of a jurisdiction (often a parliament or council). In most countries with a parliamentary system of government, acts of parliame ...

was passed in 1852, under the provisions of which a new cattle market

In economics, a market is a composition of systems, institutions, procedures, social relations or infrastructures whereby parties engage in exchange. While parties may exchange goods and services by barter, most markets rely on sellers offering ...

should be constructed at Copenhagen Fields, Islington

Islington () is a district in the north of Greater London, England, and part of the London Borough of Islington. It is a mainly residential district of Inner London, extending from Islington's High Street to Highbury Fields, encompassing the ...

. The Metropolitan Cattle Market

The Metropolitan Cattle Market (later Caledonian Market), just off the Caledonian Road in the parish of Islington (now the London Borough of Islington) was built by the City of London Corporation and was opened in June 1855 by Prince Albert. ...

opened in 1855, leaving West Smithfield as waste ground for about ten years during the construction of the new market.

Victorian Smithfield: meat and poultry market

The present Smithfield

The present Smithfield meat market

A meat market is, traditionally, a marketplace where meat is sold, often by a butcher. It is a specialized wet market. The term is sometimes used to refer to a meat retail store or butcher's shop, in particular in North America. During the mid ...

on Charterhouse Street

Charterhouse Street is a street on the north side of Smithfield in the City of London. The road forms part of the City’s boundary with the neighbouring London Boroughs of Islington and Camden. It connects Charterhouse Square and Holborn Circ ...

was established by Act of Parliament

Acts of Parliament, sometimes referred to as primary legislation, are texts of law passed by the legislative body of a jurisdiction (often a parliament or council). In most countries with a parliamentary system of government, acts of parliame ...

: the Metropolitan Meat and Poultry Market Act 1860. It is a large market with permanent buildings, designed by architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

Sir Horace Jones

Sir Horace Jones (20 May 1819 – 21 May 1887) was an English architect particularly noted for his work as architect and surveyor to the City of London from 1864 until his death. He served as president of the Royal Institute of British Architec ...

, who also designed Billingsgate

Billingsgate is one of the 25 Wards of the City of London. This small City Ward is situated on the north bank of the River Thames between London Bridge and Tower Bridge in the south-east of the Square Mile.

The modern Ward extends south to the ...

and Leadenhall

Leadenhall Market is a covered market in London, located on Gracechurch Street but with vehicular access also available via Whittington Avenue to the north and Lime Street to the south and east, and additional pedestrian access via a number o ...

markets. Work on the ''Central Market'', inspired by Italian architecture, began in 1866 and was completed in November 1868 at a cost of £993,816 (£ as of ).

The Grade II listed

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern I ...

main wings (known as ''East'' and ''West Market'') are separated by the ''Grand Avenue'', a wide roadway roofed by an elliptical arch with decorations in cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron– carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuri ...

. At the two ends of the arcade, four prominent statues represent London, Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

and Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

; they depict bronze dragons charged with the City

A city is a human settlement of notable size.Goodall, B. (1987) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography''. London: Penguin.Kuper, A. and Kuper, J., eds (1996) ''The Social Science Encyclopedia''. 2nd edition. London: Routledge. It can be def ...

's armorial bearings

A coat of arms is a heraldic visual design on an escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central element of the full heraldic achievement, which in it ...

. At the corners of the market, four octagonal pavilion towers were built, each with a dome

A dome () is an architectural element similar to the hollow upper half of a sphere. There is significant overlap with the term cupola, which may also refer to a dome or a structure on top of a dome. The precise definition of a dome has been a m ...

displaying carved stone griffin

The griffin, griffon, or gryphon ( Ancient Greek: , ''gryps''; Classical Latin: ''grȳps'' or ''grȳpus''; Late and Medieval Latin: ''gryphes'', ''grypho'' etc.; Old French: ''griffon'') is a legendary creature with the body, tail, and ...

s.

As the market was being built, a cut and cover

A tunnel is an underground passageway, dug through surrounding soil, earth or rock, and enclosed except for the entrance and exit, commonly at each end. A pipeline is not a tunnel, though some recent tunnels have used immersed tube cons ...

railway tunnel was constructed below street level to create a triangular junction with the railway between Blackfriars and Kings Cross through Snow Hill Tunnel. Closed in 1916, it has been revived and is now used for Thameslink

Thameslink is a 24-hour main-line route in the British railway system, running from , , , and via central London to Sutton, , , Rainham, , , , and . The network opened as a through service in 1988, with severe overcrowding by 1998, carrying ...

rail services. The construction of extensive railway sidings

A siding, in rail terminology, is a low-speed track section distinct from a running line or through route such as a main line, branch line, or spur. It may connect to through track or to other sidings at either end. Sidings often have lighte ...

, beneath Smithfield Park, facilitated the transfer of animal carcasses to its cold store, and directly up to the meat market via lift

Lift or LIFT may refer to:

Physical devices

* Elevator, or lift, a device used for raising and lowering people or goods

** Paternoster lift, a type of lift using a continuous chain of cars which do not stop

** Patient lift, or Hoyer lift, mobil ...

s. These sidings closed in the 1960s. They are now used as a car park, accessed via a cobbled descent at the centre of Smithfield Park. Today, much of the meat is delivered to market by road.

The first extension of Smithfield's meat market took place between 1873 and 1876 with the construction of the '' Poultry Market'' immediately west of the Central Market. A rotunda was built at the centre of the old Market Field (now West Smithfield), comprising gardens, a fountain and a ramped carriageway to the station beneath the market building. Further buildings were subsequently added to the market. The '' General Market'', built between 1879 and 1883, was intended to replace the old Farringdon Market located nearby and established for the sale of fruit and vegetables when the earlier Fleet Market was cleared to enable the laying out of Farringdon Street between 1826–1830.

A further block (also known as ''Annexe Market'' or ''Triangular Block'',) consisting of two separate structures (the ''Fish Market'' and the ''Red House''), was built between 1886 and 1899. The ''Fish Market'', built by John Mowlem & Co., was completed in 1888, one year after Sir Horace Jones' death. The ''Red House'', with its imposing red brick

A brick is a type of block used to build walls, pavements and other elements in masonry construction. Properly, the term ''brick'' denotes a block composed of dried clay, but is now also used informally to denote other chemically cured cons ...

and Portland stone

Portland stone is a limestone from the Tithonian stage of the Jurassic period quarried on the Isle of Portland, Dorset. The quarries are cut in beds of white-grey limestone separated by chert beds. It has been used extensively as a building ...

façade, was built between 1898 and 1899 for the ''London Central Markets Cold Storage Co. Ltd.''. It was one of the first cold stores to be built outside the London docks

London Docklands is the riverfront and former docks in London. It is located in inner east and southeast London, in the boroughs of Southwark, Tower Hamlets, Lewisham, Newham, and Greenwich. The docks were formerly part of the Port ...

and continued to serve Smithfield Market until the mid-1970s.

20th century

During theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, a large underground cold store at Smithfield was the theatre of secret experiments led by Dr Max Perutz on pykrete

Pykrete is a frozen ice composite, originally made of approximately 14% sawdust or some other form of wood pulp (such as paper) and 86% ice by weight (6 to 1 by weight). During World War II, Geoffrey Pyke proposed it as a candidate material ...

, a mixture of ice and woodpulp

Pulp is a lignocellulosic fibrous material prepared by chemically or mechanically separating cellulose fibers from wood, fiber crops, waste paper, or rags. Mixed with water and other chemical or plant-based additives, pulp is the major raw mate ...

, believed to be possibly tougher than steel

Steel is an alloy made up of iron with added carbon to improve its strength and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Many other elements may be present or added. Stainless steels that are corrosion- and oxidation-resistan ...

. Perutz's work, inspired by Geoffrey Pyke and part of Project Habakkuk

Project Habakkuk or Habbakuk (spelling varies) was a plan by the British during the Second World War to construct an aircraft carrier out of pykrete (a mixture of wood pulp and ice) for use against German U-boats in the mid- Atlantic, which w ...

, was meant to test the viability of pykrete as a material to construct floating airstrip

An aerodrome (Commonwealth English) or airdrome (American English) is a location from which aircraft flight operations take place, regardless of whether they involve air cargo, passengers, or neither, and regardless of whether it is for publ ...

s in the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

to allow refuelling of cargo plane

A cargo aircraft (also known as freight aircraft, freighter, airlifter or cargo jet) is a fixed-wing aircraft that is designed or converted for the carriage of cargo rather than passengers. Such aircraft usually do not incorporate passenger a ...

s in support of Admiral the Earl Mountbatten's operations. The experiments were carried out by Perutz and his colleagues in a refrigerated meat locker in a Smithfield Market butcher's basement, behind a protective screen of frozen animal carcasses. These experiments became obsolete with the development of longer-range aircraft

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to flight, fly by gaining support from the Atmosphere of Earth, air. It counters the force of gravity by using either Buoyancy, static lift or by using the Lift (force), dynamic lift of an airfoil, or in ...

, resulting in abandonment of the project.

Towards the very end of the Second World War, a V-2

The V-2 (german: Vergeltungswaffe 2, lit=Retaliation Weapon 2), with the technical name ''Aggregat 4'' (A-4), was the world’s first long-range guided ballistic missile. The missile, powered by a liquid-propellant rocket engine, was develope ...

rocket struck the north side of Charterhouse Street

Charterhouse Street is a street on the north side of Smithfield in the City of London. The road forms part of the City’s boundary with the neighbouring London Boroughs of Islington and Camden. It connects Charterhouse Square and Holborn Circ ...

, near the junction with Farringdon Road

Farringdon Road is a road in Clerkenwell, London.

Route

Farringdon Road is part of the A201 route connecting King's Cross to Elephant and Castle. It goes southeast from King's Cross, crossing Rosebery Avenue, then turns south, crossing ...

(1945). The explosion caused massive damage to the market buildings, affected the railway tunnel structure below, and caused more than 110 deaths.

On 23 January 1958, a fire broke out in the basement of Union Cold Storage Co at the Smithfield Poultry Market

Smithfield Poultry Market was constructed in 1961–1963 to replace a Victorian market building in Smithfield, London, which was destroyed by fire in 1958. Its roof is claimed to be the largest concrete shell structure ever built, and the larg ...