Weltgeist on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Geist'' () is a

in Wolfgang Pfeifer, ''Etymologisches Wörterbuch'' ([1989] 2010). Numerous German compounds, compounds are formed in the 18th to 19th centuries, some of them loan translations of French expressions, such as ''Geistesgegenwart'' = ''présence d'esprit'' ("mental presence, acuity"), ''Geistesabwesenheit'' = ''absence d’esprit'' ("mental absence, distraction"), ''geisteskrank'' "mentally ill", ''geistreich'' "witty, intellectually brilliant", ''geistlos'' "unintelligent, unimaginative, vacuous" etc. It is from these developments that certain German compounds containing ''-geist'' have been loaned into English, such as ''Zeitgeist''.''Zeitgeist'' "spirit of the epoch" and ''Nationalgeist'' "spirit of a nation" in L. Meister, ''Eine kurze Geschichte der Menschenrechte'' (1789). ''der frivole Welt- und Zeitgeist'' ("the frivolous spirit of the world and the time") in Lavater, ''Handbibliothek für Freunde'' 5 (1791), p. 57. ''Zeitgeist'' is popularized by Johann Gottfried Herder, Herder and Goethe

Zeitgeist

in Grimm, ''Deutsches Wörterbuch''. German ''Geist'' in this particular sense of "mind, wit, erudition; intangible essence, spirit" has no precise English-language equivalent, for which reason translators sometimes retain ''Geist'' as a German loanword. There is a second word for ''ghost'' in German: '':de:Gespenst, das Gespenst'' (neutral gender). ''Der Geist'' is used slightly more often to refer to a ghost (in the sense of flying white creature) than ''das Gespenst''. The corresponding adjectives are ''gespenstisch'' ("ghostly", "spooky") and ''gespensterhaft'' ("ghost-like"). A ''Gespenst'' is described in German as ''spukender Totengeist'', a "spooking ghost of the dead". The adjectives ''geistig'' and ''geistlich'' on the other hand, can not be used to describe something spooky, as ''geistig'' means "mental", and ''geistlich'' means either "spiritual" or refers to employees of the church. ''Geisterhaft'' would also mean, like ''gespensterhaft'', "ghost-like". While "spook" means ''der Spuk'' (male gender), the adjective of this word is only used in its English form, ''spooky''. The more common German adjective would be ''gruselig'', deriving from ''der Grusel'' (''das ist gruselig'', colloquially: ''das ist spooky'', meaning "that is spooky").

The term was notably embraced by Hegel and his followers in the early 19th century.

For the 19th century, the term as used by The Phenomenology of Spirit, Hegel (1807) became prevalent, less in the sense of an animating principle of nature or the universe but as the invisible force advancing World history (field), world history:

:''Im Gange der Geschichte ist das eine wesentliche Moment die Erhaltung eines Volkes [...] das andere Moment aber ist, daß der Bestand eines Volksgeistes, wie er ist, durchbrochen wird, weil er sich ausgeschöpft und ausgearbeitet hat, daß die Weltgeschichte, der Weltgeist fortgeht.''

:"In the course of history one relevant factor is the preservation of a Volk, nation [...] while the other factor is that the continued existence of a national spirit [''Volksgeist''] is interrupted because it has exhausted and spent itself, so that world history, the world spirit [''Weltgeist''], proceeds."

Hegel's description of Napoleon as "the world-soul on horseback" (''die Weltseele zu Pferde'') became proverbial.

The phrase is a shortened paraphrase of Hegel's words in a letter written on 13 October 1806, the day before the Battle of Jena, to his friend Friedrich Immanuel Niethammer:

The term was notably embraced by Hegel and his followers in the early 19th century.

For the 19th century, the term as used by The Phenomenology of Spirit, Hegel (1807) became prevalent, less in the sense of an animating principle of nature or the universe but as the invisible force advancing World history (field), world history:

:''Im Gange der Geschichte ist das eine wesentliche Moment die Erhaltung eines Volkes [...] das andere Moment aber ist, daß der Bestand eines Volksgeistes, wie er ist, durchbrochen wird, weil er sich ausgeschöpft und ausgearbeitet hat, daß die Weltgeschichte, der Weltgeist fortgeht.''

:"In the course of history one relevant factor is the preservation of a Volk, nation [...] while the other factor is that the continued existence of a national spirit [''Volksgeist''] is interrupted because it has exhausted and spent itself, so that world history, the world spirit [''Weltgeist''], proceeds."

Hegel's description of Napoleon as "the world-soul on horseback" (''die Weltseele zu Pferde'') became proverbial.

The phrase is a shortened paraphrase of Hegel's words in a letter written on 13 October 1806, the day before the Battle of Jena, to his friend Friedrich Immanuel Niethammer:

Hegel's Spirit/Mind

from Hegel.net (Hegel's various uses of the term ''Geist'' based on the entry from ''Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, Encyclopædia Britannica 11th Edition'')

Christian Adolph Klotz

in: Meyers Konversations-Lexikon, 4. Aufl., 1888, Vol. 9, Page 859 * {{Authority control Philosophy of mind Spirituality Enlightenment philosophy German words and phrases Concepts in metaphysics German philosophy German idealism Johann Wolfgang von Goethe Hegelianism

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

noun with a significant degree of importance in German philosophy

German philosophy, here taken to mean either (1) philosophy in the German language or (2) philosophy by Germans, has been extremely diverse, and central to both the analytic and continental traditions in philosophy for centuries, from Gottfried ...

. Its semantic field corresponds to English ghost, spirit, mind, intellect. Some English translators resort to using "spirit/mind" or "spirit (mind)" to help convey the meaning of the term.

''Geist'' is also a central concept in Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's 1807 ''The Phenomenology of Spirit'' (''Phänomenologie des Geistes''). Notable compounds, all associated with Hegel's view of World history (field), world history of the late 18th century, include ''Weltgeist'' "world-spirit", ''Volksgeist'' "national spirit" and ''Zeitgeist'' "spirit of the age".

Etymology and translation

German ''Geist'' (masculine gender: ''der Geist'') continues Old High German ''geist'', attested as the translation of Latin ''spiritus''. It is the direct cognate of English '':wikt:ghost, ghost'', from a West Germanic ''gaistaz''. Its derivation from a PIE root ''g̑heis-'' "to be agitated, frightened" suggests that the Germanic word originally referred to frightening (c.f. English :wikt:ghastly, ghastly) apparitions or ghosts, and may also have carried the connotation of "ecstatic agitation, ''odhr, furor''" related to the cult of Germanic Mercury. As the translation of biblical Latin ''spiritus'' (Greek πνεῦμα) "pneuma, spirit, breath" the Germanic word acquires a Christian meaning from an early time, notably in reference to the Holy Spirit (Old English ''sē hālga gāst'' "the Holy Ghost", OHG '' ther heilago geist'', Modern German ''der Heilige Geist''). The English word is in competition with Latinate ''spirit'' from the Middle English period, but its broader meaning is preserved well into the early modern period. The German noun much like English ''spirit'' could refer to spooks or ghostly apparitions of the dead, to the religious concept, as in the Holy Spirit, as well as to the "spirit of wine", i.e. ethanol. However, its special meaning of "mind, intellect" never shared by English ''ghost'' is acquired only in the 18th century, under the influence of French ''esprit''. In this sense it became extremely productive in the German language of the 18th century in general as well as in 18th-century German philosophy. ''Geist'' could now refer to the quality of intellectual brilliance, to wit, innovation, erudition, etc. It is also in this time that the adjectival distinction of ''geistlich'' "spiritual, pertaining to religion" vs. ''geistig'' "intellectual, pertaining to the mind" begins to be made. Reference to spooks or ghosts is made by the adjective ''geisterhaft'' "ghostly, spectral".Geistin Wolfgang Pfeifer, ''Etymologisches Wörterbuch'' ([1989] 2010). Numerous German compounds, compounds are formed in the 18th to 19th centuries, some of them loan translations of French expressions, such as ''Geistesgegenwart'' = ''présence d'esprit'' ("mental presence, acuity"), ''Geistesabwesenheit'' = ''absence d’esprit'' ("mental absence, distraction"), ''geisteskrank'' "mentally ill", ''geistreich'' "witty, intellectually brilliant", ''geistlos'' "unintelligent, unimaginative, vacuous" etc. It is from these developments that certain German compounds containing ''-geist'' have been loaned into English, such as ''Zeitgeist''.''Zeitgeist'' "spirit of the epoch" and ''Nationalgeist'' "spirit of a nation" in L. Meister, ''Eine kurze Geschichte der Menschenrechte'' (1789). ''der frivole Welt- und Zeitgeist'' ("the frivolous spirit of the world and the time") in Lavater, ''Handbibliothek für Freunde'' 5 (1791), p. 57. ''Zeitgeist'' is popularized by Johann Gottfried Herder, Herder and Goethe

Zeitgeist

in Grimm, ''Deutsches Wörterbuch''. German ''Geist'' in this particular sense of "mind, wit, erudition; intangible essence, spirit" has no precise English-language equivalent, for which reason translators sometimes retain ''Geist'' as a German loanword. There is a second word for ''ghost'' in German: '':de:Gespenst, das Gespenst'' (neutral gender). ''Der Geist'' is used slightly more often to refer to a ghost (in the sense of flying white creature) than ''das Gespenst''. The corresponding adjectives are ''gespenstisch'' ("ghostly", "spooky") and ''gespensterhaft'' ("ghost-like"). A ''Gespenst'' is described in German as ''spukender Totengeist'', a "spooking ghost of the dead". The adjectives ''geistig'' and ''geistlich'' on the other hand, can not be used to describe something spooky, as ''geistig'' means "mental", and ''geistlich'' means either "spiritual" or refers to employees of the church. ''Geisterhaft'' would also mean, like ''gespensterhaft'', "ghost-like". While "spook" means ''der Spuk'' (male gender), the adjective of this word is only used in its English form, ''spooky''. The more common German adjective would be ''gruselig'', deriving from ''der Grusel'' (''das ist gruselig'', colloquially: ''das ist spooky'', meaning "that is spooky").

Hegelianism

''Geist'' is a central concept in Hegel's ''The Phenomenology of Spirit'' (''Phänomenologie des Geistes''). According to some interpretations, the ''Weltgeist'' ("world spirit") is not an actual object or a transcendental, Godlike thing, but a means of philosophizing about history. ''Weltgeist'' is effected in history through the mediation of various ''Volksgeister'' ("national spirits"), the hero, great men of history, such as Napoleon, are the "concrete (philosophy), concrete universality (philosophy), universal". This has led some to claim that Hegel favored the great man theory, although his philosophy of history, in particular concerning the role of the "universality (philosophy), universal state" (''Universalstaat'', which means a universal "order" or "statute" rather than "State (polity), state"), and of an "End of History" is much more complex. For Hegel, the great hero is unwittingly utilized by ''Geist'' or ''absolute spirit'', by a "ruse of reason" as he puts it, and is irrelevant to history once his historic mission is accomplished; he is thus subjected to the teleology, teleological principle of history, a principle which allows Hegel to reread the history of philosophy as culminating in his philosophy of history. ''Weltgeist'', the world spirit concept, designates an idealism, idealistic principle of world explanation, which can be found from the beginnings of philosophy up to more recent time. The concept of world spirit was already accepted by the idealistic schools of ancient Indian philosophy, whereby one explained objective reality as its product. (See metaphysical objectivism) In the early philosophy of Greek antiquity, Socrates, Plato and Aristotle all paid homage, amongst other things, to the concept of world spirit. Hegel later based his philosophy of history on it.''Weltgeist''

''Weltgeist'' ("world-spirit") is older than the 18th century, at first (16th century) in the sense of "secularism, impiety, irreligiosity" (''spiritus mundi''), in the 17th century also personalised in the sense of "man of the world", "mundane or secular person". Also from the 17th century, ''Weltgeist'' acquired a philosophical or spiritual sense of "world-spirit" or "world-soul" (''anima mundi, spiritus universi'') in the sense of Panentheism, a spiritual essence permeating all of nature, or the active principle animating the universe, including the physical sense, such as the attraction between magnetic force, magnet and iron or between Gravity, Moon and tide. This idea of ''Weltgeist'' in the sense of ''anima mundi'' became very influential in 18th-century German philosophy. In philosophical contexts, ''der Geist'' on its own could refer to this concept, as in Christian Thomasius, ''Versuch vom Wesen des Geistes'' (1709). Belief in a ''Weltgeist'' as animating principle immanent to the universe became dominant in German thought due to the influence of Goethe, in the later part of the 18th century. Already in the poetical language of :de:Johann Ulrich von König (d. 1745), the ''Weltgeist'' appears as the active, masculine principle opposite the feminine principle of Nature. ''Weltgeist'' in the sense of Goethe comes close to being a synonym of God and can be attributed agency and will. Johann Gottfried Herder, Herder, who tended to prefer the form ''Weltengeist'' (as it were "spirit of worlds"), pushes this to the point of composing prayers addressed to this world-spirit: :'' O Weltengeist, Bist du so gütig, wie du mächtig bist, Enthülle mir, den du mitfühlend zwar, Und doch so grausam schufst, erkläre mir Das Loos der Fühlenden, die durch mich leiden.'' :"O World-spirit, be as benevolent as you are powerful and reveal to me, whom you have created with compassion and yet cruelly, explain to me the lot of the sentient, who suffer through me" The term was notably embraced by Hegel and his followers in the early 19th century.

For the 19th century, the term as used by The Phenomenology of Spirit, Hegel (1807) became prevalent, less in the sense of an animating principle of nature or the universe but as the invisible force advancing World history (field), world history:

:''Im Gange der Geschichte ist das eine wesentliche Moment die Erhaltung eines Volkes [...] das andere Moment aber ist, daß der Bestand eines Volksgeistes, wie er ist, durchbrochen wird, weil er sich ausgeschöpft und ausgearbeitet hat, daß die Weltgeschichte, der Weltgeist fortgeht.''

:"In the course of history one relevant factor is the preservation of a Volk, nation [...] while the other factor is that the continued existence of a national spirit [''Volksgeist''] is interrupted because it has exhausted and spent itself, so that world history, the world spirit [''Weltgeist''], proceeds."

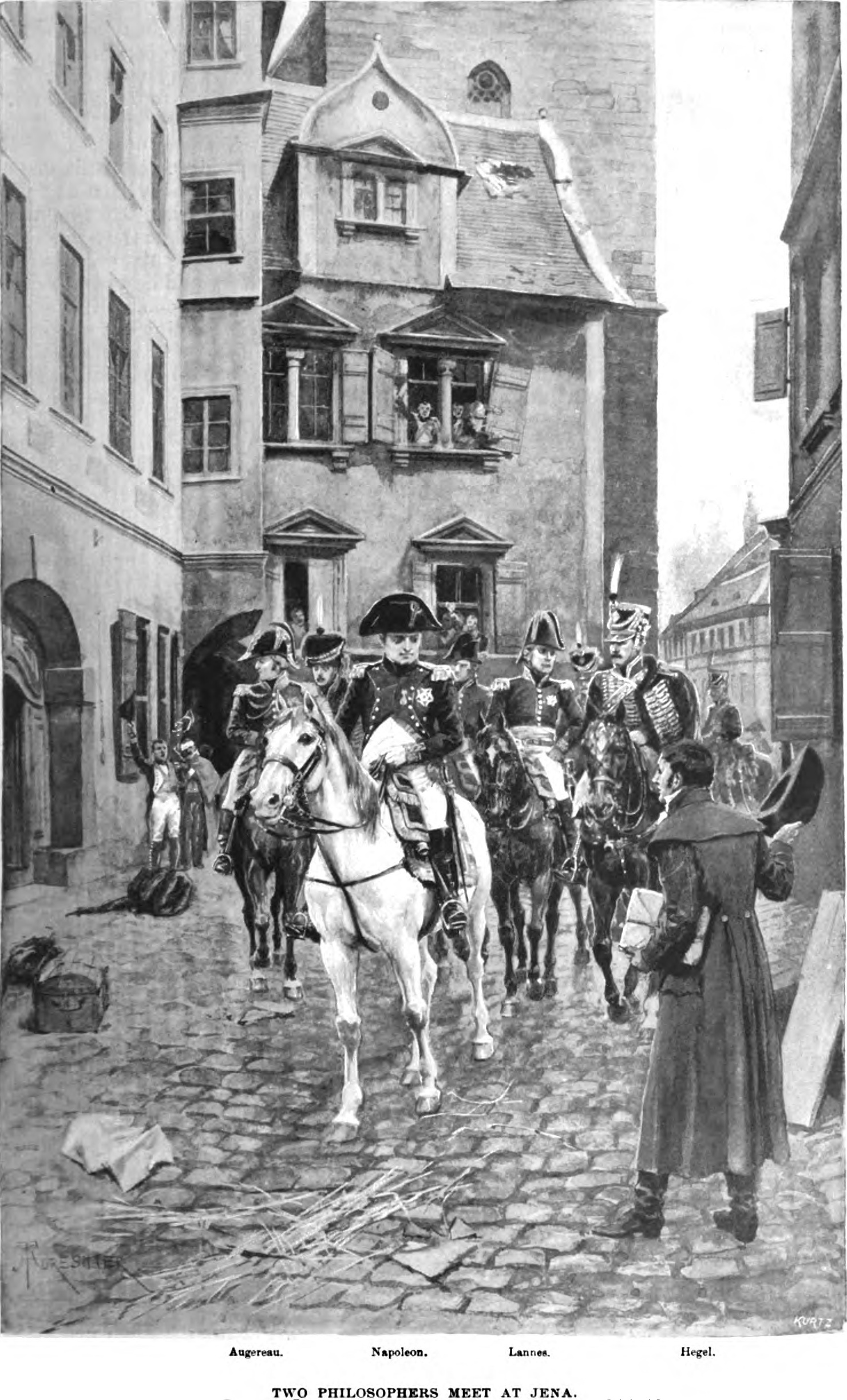

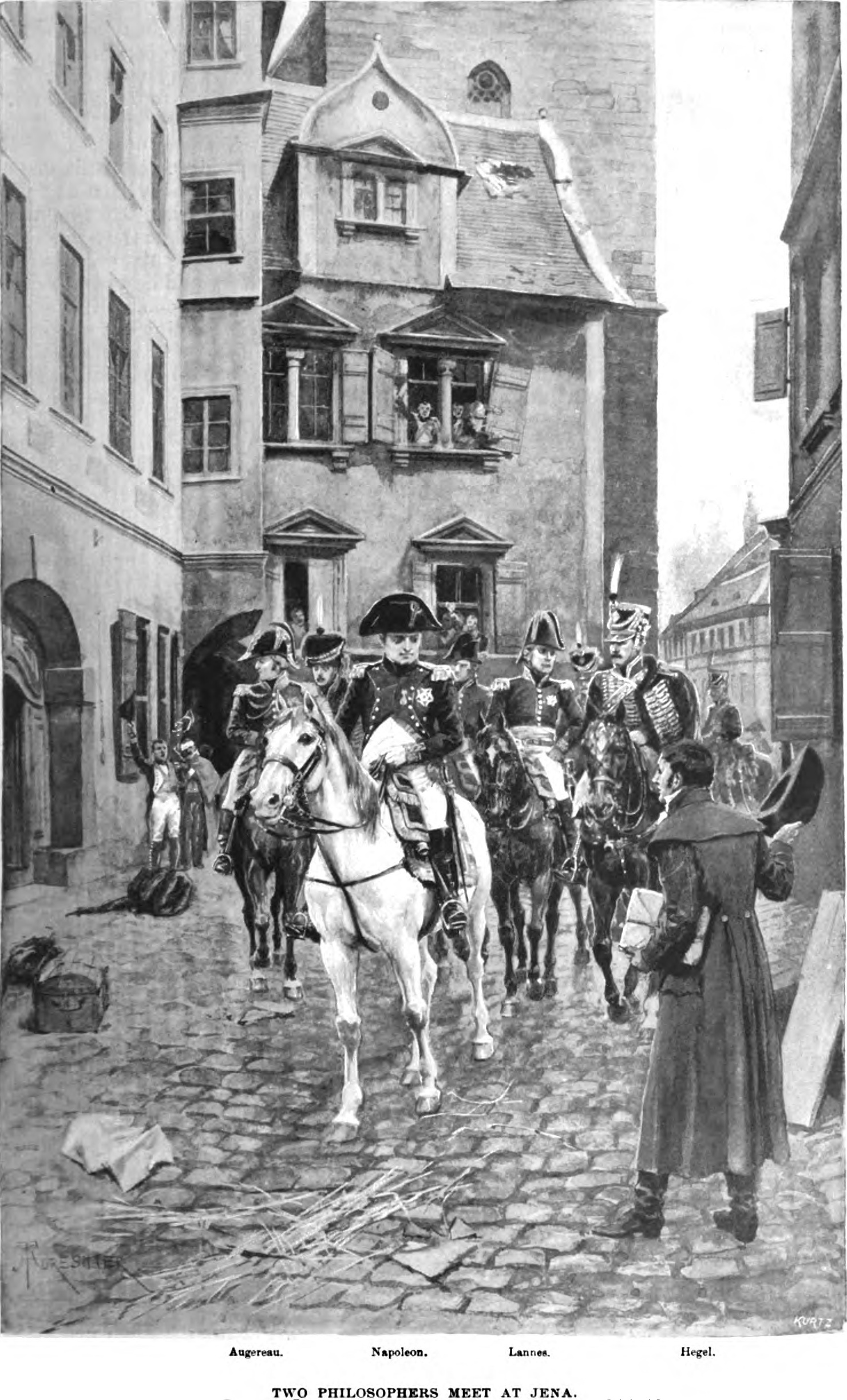

Hegel's description of Napoleon as "the world-soul on horseback" (''die Weltseele zu Pferde'') became proverbial.

The phrase is a shortened paraphrase of Hegel's words in a letter written on 13 October 1806, the day before the Battle of Jena, to his friend Friedrich Immanuel Niethammer:

The term was notably embraced by Hegel and his followers in the early 19th century.

For the 19th century, the term as used by The Phenomenology of Spirit, Hegel (1807) became prevalent, less in the sense of an animating principle of nature or the universe but as the invisible force advancing World history (field), world history:

:''Im Gange der Geschichte ist das eine wesentliche Moment die Erhaltung eines Volkes [...] das andere Moment aber ist, daß der Bestand eines Volksgeistes, wie er ist, durchbrochen wird, weil er sich ausgeschöpft und ausgearbeitet hat, daß die Weltgeschichte, der Weltgeist fortgeht.''

:"In the course of history one relevant factor is the preservation of a Volk, nation [...] while the other factor is that the continued existence of a national spirit [''Volksgeist''] is interrupted because it has exhausted and spent itself, so that world history, the world spirit [''Weltgeist''], proceeds."

Hegel's description of Napoleon as "the world-soul on horseback" (''die Weltseele zu Pferde'') became proverbial.

The phrase is a shortened paraphrase of Hegel's words in a letter written on 13 October 1806, the day before the Battle of Jena, to his friend Friedrich Immanuel Niethammer:

I saw the Emperor – this world-soul – riding out of the city on reconnaissance. It is indeed a wonderful sensation to see such an individual, who, concentrated here at a single point, astride a horse, reaches out over the world and masters it.The letter was not published in Hegel's time, but the expression was attributed to Hegel anecdotally, appearing in print from 1859. It is used without attribution by Meyer Kayserling in his ''Sephardim'' (1859:103), and is apparently not recognized as a reference to Hegel by the reviewer in ''Göttingische gelehrte Anzeigen'', who notes it disapprovingly, as one of Kayserling's "bad jokes" (''schlechte Witze''). The phrase became widely associated with Hegel later in the 19th century.

''Volksgeist''

''Volksgeist'' or ''Nationalgeist'' refers to a "spirit" of an individual Volk, people (''Volk''), its "national spirit" or "national character". The term ''Nationalgeist'' is used in the 1760s by Justus Möser and by Johann Gottfried Herder. The term ''Nation'' at this time is used in the sense of '':wikt:natio#Latin, natio'' "nation, ethnic group, race", mostly replaced by the term ''Volk'' after 1800. In the early 19th century, the term ''Volksgeist'' was used by Friedrich Carl von Savigny in order to express the "popular" sense of justice. Savigniy explicitly referred to the concept of an ''esprit des nations '' used by Voltaire. and of the ''esprit général'' invoked by Montesquieu. Hegel uses the term in his ''Lectures on the Philosophy of History''. Based on the Hegelian use of the term, Wilhelm Wundt, Moritz Lazarus and Heymann Steinthal in the mid-19th-century established the field of ''Völkerpsychologie'' ("psychology of nations"). In Germany the concept of Volksgeist has developed and changed its meaning through eras and fields. The most important examples are: In the literary field, August Wilhelm Schlegel, Schlegel and the Brothers Grimm. In the history of cultures, Johann Gottfried Herder, Herder. In the history of the State or political history, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Hegel. In the field of law, Friedrich Carl von Savigny, Savigny and in the field of psychology Wilhelm Wundt, Wundt. This means that the concept is ambiguous. Furthermore it is not limited to Romanticism as it is commonly known. The concept of was also influential in American cultural anthropology. According to the historian of anthropology George W. Stocking, Jr., "… one may trace the later American anthropological idea of culture back through Bastian's Volkergedanken and the folk psychologist's Volksgeister to Wilhelm von Humboldt's Nationalcharakter – and behind that, although not without a paradoxical and portentous residue of conceptual and ideological ambiguity, to the Herderian ideal of Volksgeist."''Zeitgeist''

The compound ''Zeitgeist'' (;, "spirit of the age" or "spirit of the times") similarly to ''Weltgeist'' describes an invisible agent or force dominating the characteristics of a given epoch in World history (field), world history. The term is now mostly associated with Hegel, contrasting with Hegel's use of ''Volksgeist'' "national spirit" and ''Weltgeist'' "world-spirit", but its coinage and popularization precedes Hegel, and is mostly due to Johann Gottfried Herder, Herder and Goethe. The term as used contemporarily may more pragmatically refer to a fad, fashion or fad which prescribes what is acceptable or tasteful, e.g. in the field of architecture. Hegel in ''Phenomenology of the Spirit'' (1807) uses both ''Weltgeist'' and ''Volksgeist'' but prefers the phrase ''Geist der Zeiten'' "spirit of the times" over the German compound, compound ''Zeitgeist''. Hegel believed that culture and art reflected its time. Thus, he argued that it would be impossible to produce classical art in the modern world, as modernity is essentially a "free and ethical culture".Hendrix, John Shannon. ''Aesthetics & The Philosophy Of Spirit''. New York: Peter Lang. (2005). 4, 11. The term has also been used more widely in the sense of an intellectual or aesthetic fashion or fad. For example, Charles Darwin's 1859 proposition that evolution occurs by natural selection has been cited as a case of the ''zeitgeist'' of the epoch, an idea "whose time had come", seeing that his contemporary, Alfred Russel Wallace, was outlining similar models during the same period.Hothersall, D., "History of Psychology", 2004, Similarly, intellectual fashions such as the emergence of logical positivism in the 1920s, leading to a focus on behaviorism and blank-slatism over the following decades, and later, during the 1950s to 1960s, the shift from behaviorism to post-modernism and critical theory can be argued to be an expression of the intellectual or academic "zeitgeist". ''Zeitgeist'' in more recent usage has been used by Forsyth (2009) in reference to his "theory of leadership"Forsyth, D. R. (2009). Group dynamics: New York: Wadsworth. [Chapter 9] and in other publications describing models of business or industry. Malcolm Gladwell argued in his book ''Outliers (book), Outliers'' that entrepreneurs who succeeded in the early stages of a nascent industry often share similar characteristics.See also

* * HauntologyReferences

* ''Of Spirit: Heidegger and the Question'', by Jacques Derrida. Translation by Geoffrey Bennington & Rachel Bowlby, Chicago University Press, 1989 () and 1991 () * Isaiah Berlin, Berlin, Isaiah: ''Vico and Herder. Two Studies in the History of Ideas'', London, 1976. * George W. Stocking, Jr., Stocking, George W. 1996. Volksgeist as Method and Ethic: Essays on Boasian Ethnography and the German Anthropological Tradition''.External links

Hegel's Spirit/Mind

from Hegel.net (Hegel's various uses of the term ''Geist'' based on the entry from ''Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, Encyclopædia Britannica 11th Edition'')

Christian Adolph Klotz

in: Meyers Konversations-Lexikon, 4. Aufl., 1888, Vol. 9, Page 859 * {{Authority control Philosophy of mind Spirituality Enlightenment philosophy German words and phrases Concepts in metaphysics German philosophy German idealism Johann Wolfgang von Goethe Hegelianism