Washington, D.C., in the American Civil War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

During the

During the

Despite being the nation's

Despite being the nation's

The following hospitals were located in the District of Columbia:

* Armory Square General Hospital,

* Carver General Hospital

* Campbell General Hospital

* Columbia General Hospital

* Columbian General Hospital

* Douglas General Hospital

* Emory General Hospital

*

The following hospitals were located in the District of Columbia:

* Armory Square General Hospital,

* Carver General Hospital

* Campbell General Hospital

* Columbia General Hospital

* Columbian General Hospital

* Douglas General Hospital

* Emory General Hospital

*

Old Capitol Prison

/ref>

On April 14, 1865, just days after the end of the war, Lincoln was shot in Ford's Theater by

On April 14, 1865, just days after the end of the war, Lincoln was shot in Ford's Theater by

On May 9, 1865, the new president,

On May 9, 1865, the new president,

Image:Alfred Pleasonton.jpg,

Image:Manning Force.jpg,

Image:Gettygw1m.jpg,

Image:Louis-Malesherbes-Goldsborough.jpg,

File:William Montrose Graham, Jr.jpg,

Image:Mansfield_Lovell.jpg,

Image:Robert S Ewell.png,

Other important personalities of the Civil War born in the immediate Washington area included Confederate Senator Thomas Jenkins Semmes, Union general John Milton Brannan,

NPS description of defenses

* Wert, Jeffry D., ''General James Longstreet: The Confederacy's Most Controversial Soldier: A Biography'', Simon & Schuster, 1993, . *

Washington, D.C. defenses

National Park Service

Civil War WashingtonC-SPAN American History TV Tour of Civil War Defenses of Washington, D.C.

During the

During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

(1861–1865), Washington, D.C., the capital city

A capital city or capital is the municipality holding primary status in a country, state, province, department, or other subnational entity, usually as its seat of the government. A capital is typically a city that physically encompasses t ...

of the United States, was the center of the Union war effort, which rapidly turned it from a small city into a major capital with full civic infrastructure and strong defenses.

The shock of the Union defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run

The First Battle of Bull Run (the name used by Union forces), also known as the Battle of First Manassas

in July 1861, with demoralized troops wandering the streets of the capital, caused President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

to order extensive fortifications and a large garrison

A garrison (from the French ''garnison'', itself from the verb ''garnir'', "to equip") is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a mili ...

. That required an influx of troops, military suppliers and building contractors, which would set up a new demand for accommodation, including military hospitals. The abolition of slavery in Washington in 1862 also attracted many freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom ...

to the city. Except for one attempted invasion by Confederate cavalry leader Jubal Early

Jubal Anderson Early (November 3, 1816 – March 2, 1894) was a Virginia lawyer and politician who became a Confederate States of America, Confederate general during the American Civil War. Trained at the United States Military Academy, Early r ...

in 1864, the capital remained impregnable.

When Lincoln was assassinated in Ford's Theater in April 1865, thousands flocked into Washington to view the coffin, further raising the profile of the city. The new president, Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a De ...

, wanted to dispel the funereal atmosphere and organized a program of victory parade

A victory parade is a parade held to celebrate a victory. Numerous military and sport victory parades have been held.

Military victory parades

Among the most famous parades are the victory parades celebrating the end of the First World War a ...

s, which revived public hopes for the future.

Early stages of war

Despite being the nation's

Despite being the nation's capital city

A capital city or capital is the municipality holding primary status in a country, state, province, department, or other subnational entity, usually as its seat of the government. A capital is typically a city that physically encompasses t ...

, Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

remained a small city that was virtually deserted during the torrid summertime until the outbreak of the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

. In February 1861, the Peace Congress, a last-ditch attempt by delegates from 21 of the 34 states to avert what many saw as the impending civil war, met in the city's Willard Hotel

The Willard InterContinental Washington, commonly known as the Willard Hotel, is a historic luxury Beaux-Arts hotel located at 1401 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Downtown Washington, D.C. It is currently a member oHistoric Hotels of America the offi ...

. The strenuous effort failed, and the war started in April 1861.

At first, it looked as if neighboring Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

would remain in the Union. When it unexpectedly voted for secession, there was a serious danger that the divided state of Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean t ...

would do the same, which would totally surround the capital with enemy states. President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

’s act in jailing Maryland's pro-slavery leaders without trial saved the capital from that fate.

Faced with an open rebellion that had turned hostile, Lincoln began organizing a military force to protect Washington. The Confederates desired to occupy Washington and massed to take it. On April 10 forces began to trickle into the city. On April 19, the Baltimore riot threatened the arrival of further reinforcements. Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (, ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans in ...

led the building of a railroad that circumvented Baltimore, allowing soldiers to arrive on April 25, thereby saving the capital.

Thousands of raw volunteers and many professional soldiers came to the area to fight for the Union. By mid-summer, Washington teemed with volunteer regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, service and/or a specialisation.

In Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of front-line soldiers, recruited or conscript ...

s and artillery batteries

In military organizations, an artillery battery is a unit or multiple systems of artillery, mortar systems, rocket artillery, multiple rocket launchers, surface-to-surface missiles, ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, etc., so grouped to facil ...

from throughout the North, all of which serviced by what was little more than a country town that in 1860 had only 75,800 people. George Templeton Strong's observation of Washington life led him to declare: Of all the detestable places Washington is first. Crowd, heat, bad quarters, bad fairThe city became the staging area for what became known as theare Are commonly refers to: * Are (unit), a unit of area equal to 100 m2 Are, ARE or Åre may also refer to: Places * Åre, a locality in Sweden * Åre Municipality, a municipality in Sweden ** Åre ski resort in Sweden * Are Parish, a munici ...bad smells, mosquitos, and a plague of flies transcending everything within my experience.. . Beelzebub surely reigns here, and Willard's Hotel is his temple.

Manassas campaign

The Manassas campaign was a series of military engagements in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War.

Background

Military and political situation

The Confederate forces in northern Virginia were organized into two field armies. Br ...

. When Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

Irvin McDowell

Irvin McDowell (October 15, 1818 – May 4, 1885) was a career American army officer. He is best known for his defeat in the First Battle of Bull Run, the first large-scale battle of the American Civil War. In 1862, he was given command ...

's beaten and demoralized army staggered back into Washington after the stunning Confederate victory at the First Battle of Bull Run

The First Battle of Bull Run (the name used by Union forces), also known as the Battle of First Manassas

. The realization came that the war might be prolonged caused the beginning of efforts to fortify the city to protect it from a Confederate assault. Lincoln knew that he had to have a professional and trained army to protect the capital area and so began by organizing the Department on the Potomac on August 4, 1861, and the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confede ...

16 days later.

Most residents embraced the arriving troops, despite pockets of apathy and Confederate sympathizers. Upon hearing a Union regiment singing "John Brown's Body

"John Brown's Body" (originally known as "John Brown's Song") is a United States marching song about the abolitionist John Brown. The song was popular in the Union during the American Civil War. The tune arose out of the folk hymn tradition o ...

" as the soldiers marched beneath her window, the resident Julia Ward Howe

Julia Ward Howe (; May 27, 1819 – October 17, 1910) was an American author and poet, known for writing the " Battle Hymn of the Republic" and the original 1870 pacifist Mother's Day Proclamation. She was also an advocate for abolitionism ...

wrote the patriotic "Battle Hymn of the Republic

The "Battle Hymn of the Republic", also known as "Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory" or "Glory, Glory Hallelujah" outside of the United States, is a popular American patriotic song written by the abolitionist writer Julia Ward Howe.

Howe wrote her l ...

" to the same tune.

The significant expansion of the federal government to administer the ever-expanding war effort and its legacies, such as veterans' pensions, led to notable growth in the city's population, especially in 1862 and 1863, as the military forces and the supporting infrastructure dramatically expanded from early war days. The 1860 Census had put the population at just over 75,000 persons, but by 1870, the district's population had grown to nearly 132,000. Warehouses, supply depots, ammunition dumps, and factories were established to provide and distribute material

Material is a substance or mixture of substances that constitutes an object. Materials can be pure or impure, living or non-living matter. Materials can be classified on the basis of their physical and chemical properties, or on their geolo ...

for the Union armies, and civilian workers and contractors flocked to the city.

Slavery was abolished throughout the district on April 16, 1862, eight months before Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War, Civil War. The Proclamation c ...

, with the passage of the Compensated Emancipation Act

An Act for the Release of certain Persons held to Service or Labor in the District of Columbia, 37th Cong., Sess. 2, ch. 54, , known colloquially as the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act or simply Compensated Emancipation Act, w ...

. Washington became a popular place for formerly enslaved people to congregate, and many were employed in constructing the ring of fortresses that eventually surrounded the city.

Defense

At the beginning of the war, Washington's only defense was one old fort, Fort Washington, away to the south, and the Union Army soldiers themselves.NPS description of defenses When Maj. Gen.George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

assumed command of the Department of the Potomac on August 17, 1861, he became responsible for the capital's defense.Eicher, p. 843. McClellan began by laying out lines for a complete ring of entrenchments and fortifications

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''face ...

that would cover of land. He built enclosed forts on high hills around the city and placed well-protected batteries of field artillery

Field artillery is a category of mobile artillery used to support armies in the field. These weapons are specialized for mobility, tactical proficiency, short range, long range, and extremely long range target engagement.

Until the early 20t ...

in the gaps between these forts,Catton, p. 61. augmenting the 88 guns already placed on the defensive line facing Virginia and south. In between the batteries, interconnected rifle pits were dug, allowing highly-effective co-operative fire. That layout, once complete, would make the city one of the most heavily-defended locations in the world and almost unassailable by nearly any number of men.

The capital's defenses, for the most part, deterred the Confederate Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighti ...

from attacking. One notable exception was during the Battle of Fort Stevens

The Battle of Fort Stevens was an American Civil War battle fought July 11–12, 1864, in what is now Northwest Washington, D.C., as part of the Valley Campaigns of 1864 between forces under Confederate Lieutenant General Jubal Early and ...

on July 11–12, 1864 in which Union soldiers repelled troops under the command of Confederate Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on th ...

Jubal A. Early

Jubal Anderson Early (November 3, 1816 – March 2, 1894) was a Virginia lawyer and politician who became a Confederate general during the American Civil War. Trained at the United States Military Academy, Early resigned his U.S. Army commis ...

. That battle was the first time since the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

that a U.S. president came under enemy fire in wartime when Lincoln visited the fort to observe the fighting.

By 1865, the defenses of Washington were most stout and amply covered both land and sea approaches. When the war ended, of line included at least 68 forts and over of rifle pits and were supported by of military-only roads and four individual picket stations. Also, 93 separate batteries of artillery had been placed on this line, comprising over 1,500 guns, both field and siege varieties, as well as mortars.

Military formations

*Owens Company, District of Columbia cavalry *8 Battalions, District of Columbia Infantry *1st Regiment, District of Columbia Infantry *2nd Regiment, District of Columbia Infantry *Unassigned District of Columbia Colored *Unassigned District of Columbia VolunteersHospitals

Hospitals in the Washington area became significant providers of medical services to wounded soldiers needing long-term care after they had been transported to the city from the front lines over the Long Bridge or by steamboat at the Wharf. The following hospitals were located in the District of Columbia:

* Armory Square General Hospital,

* Carver General Hospital

* Campbell General Hospital

* Columbia General Hospital

* Columbian General Hospital

* Douglas General Hospital

* Emory General Hospital

*

The following hospitals were located in the District of Columbia:

* Armory Square General Hospital,

* Carver General Hospital

* Campbell General Hospital

* Columbia General Hospital

* Columbian General Hospital

* Douglas General Hospital

* Emory General Hospital

* Finley General Hospital

Finley General Hospital was a Union Army hospital which operated near Washington, D.C., during the Civil War. It operated from 1862 to 1865.

The hospital was set up with 1,061 beds. On December 17, 1864, 755 beds were occupied.

Location

The prec ...

* Freedman General Hospital

* Harewood General Hospital

* Judiciary Square General Hospital

* Kalorama General Hospital

* Lincoln General Hospital

* Mount Pleasant General Hospital

* Ricord General Hospital

* Stanton General Hospital

* Seminary General Hospital

* Stone General Hospital

More than 20,000 injured or ill soldiers received treatment in an array of permanent and temporary hospitals in the capital, including the U.S. Patent Office and for a time the Capitol itself. Among the notables who served in nursing were the American Red Cross

The American Red Cross (ARC), also known as the American National Red Cross, is a non-profit humanitarian organization that provides emergency assistance, disaster relief, and disaster preparedness education in the United States. It is the des ...

founder Clara Barton

Clarissa Harlowe Barton (December 25, 1821 – April 12, 1912) was an American nurse who founded the American Red Cross. She was a hospital nurse in the American Civil War, a teacher, and a patent clerk. Since nursing education was not then very ...

as well as Dorothea Dix

Dorothea Lynde Dix (April 4, 1802July 17, 1887) was an American advocate on behalf of the indigent mentally ill who, through a vigorous and sustained program of lobbying state legislatures and the United States Congress, created the first gen ...

, who served as superintendent of female nurses in Washington. The novelist Louisa May Alcott

Louisa May Alcott (; November 29, 1832March 6, 1888) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet best known as the author of the novel ''Little Women'' (1868) and its sequels ''Little Men'' (1871) and '' Jo's Boys'' (1886). Raised in ...

served at the Union Hospital in Georgetown. The poet Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among ...

served as a hospital volunteer, and in 1865, he published his famous poem "The Wound-Dresser." The United States Sanitary Commission

The United States Sanitary Commission (USSC) was a private relief agency created by federal legislation on June 18, 1861, to support sick and wounded soldiers of the United States Army (Federal / Northern / Union Army) during the American Civil ...

had a significant presence in Washington, as did the United States Christian Commission The United States Christian Commission (USCC) was an organization that furnished supplies, medical services, and religious literature to Union troops during the American Civil War. It combined religious support with social services and recreationa ...

and other relief agencies. The Freedman's Hospital was established in 1862 to serve the needs of the growing population of freed slaves.

Later stages of war

As the war progressed, the overcrowding severely strained the city's water supply. The Army Corps of Engineers constructed a new aqueduct that brought of fresh water to the city each day. Police and fire protection was increased, and work resumed to complete the unfinished dome of the Capitol Building. However, for most of the war, Washington suffered from unpaved streets, poor sanitation and garbage collection, swarms of mosquitos facilitated by the dank canals and sewers, and poor ventilation in most public and private buildings. That would change in the decade to follow under the leadership of District Governor Alexander "Boss" Shepherd. Important political and military prisoners were often housed in theOld Capitol Prison

The Old Brick Capitol in Washington, D.C., served as the temporary Capitol of the United States from 1815 to 1819. The building was a private school, a boarding house, and, during the American Civil War, a prison known as the Old Capitol Pris ...

in Washington, including accused spies Rose Greenhow

Rose O'Neal Greenhow (1813– October 1, 1864) was a renowned Confederate spy during the American Civil War. A socialite in Washington, D.C., during the period before the war, she moved in important political circles and cultivated friendsh ...

and Belle Boyd

Isabella Maria Boyd (May 9, 1844The date in the Boyd Family Bible is May 4, 1844 (), but Boyd insisted that it was 1844 and that the entry was in error. () See also . Despite Boyd's assertion, many sources give the year of birth as 1844 and the ...

as well as partisan ranger John S. Mosby. One inmate, Henry Wirz

Henry Wirz (born Hartmann Heinrich Wirz, November 25, 1823 – November 10, 1865) was a Swiss-American officer of the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. He was the commandant of the stockade of Camp Sumter, a Confederate ...

, the commandant of the Andersonville Prison in Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

was hanged in the yard of the prison shortly after the war for his cruelty and neglect toward the Union prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

./ref>

Lincoln's assassination

On April 14, 1865, just days after the end of the war, Lincoln was shot in Ford's Theater by

On April 14, 1865, just days after the end of the war, Lincoln was shot in Ford's Theater by John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth (May 10, 1838 – April 26, 1865) was an American stage actor who assassinated United States President Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. A member of the prominent 19th-century Booth ...

during the play ''Our American Cousin

''Our American Cousin'' is a three-act play by English playwright Tom Taylor. It is a farce featuring awkward, boorish American Asa Trenchard, who is introduced to his aristocratic English relatives when he goes to England to claim the family e ...

''. At 7:22 the next morning, Lincoln died in the house across the street, the first American president to be assassinated

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have ...

. Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Edwin M. Stanton said, "Now he belongs to the ages" (or perhaps "angels"). The residents and visitors to the city experienced a wide array of reactions, from stunned disbelief to rage. Stanton immediately closed off most major roads and bridges, and the city was placed under martial law. Scores of residents and workers were questioned during the growing investigation, and some were detained or arrested on suspicion of having aided the assassins or for a perception that they were withholding information.

Lincoln's body was displayed in the Capitol rotunda

The United States Capitol rotunda is the tall central rotunda of the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C. It has been described as the Capitol's "symbolic and physical heart". Built between 1818 and 1824, the rotunda is located below the ...

, and thousands of Washington residents and as throngs of visitors stood in long queues for hours to glimpse the fallen president. Hotels and restaurants were filled to capacity, bringing an unexpected windfall to their owners. Following the identification and eventual arrest of the actual conspirators, the city was the site of the trial and execution of several of the assassins, and Washington was again the center of the nation's media attention.

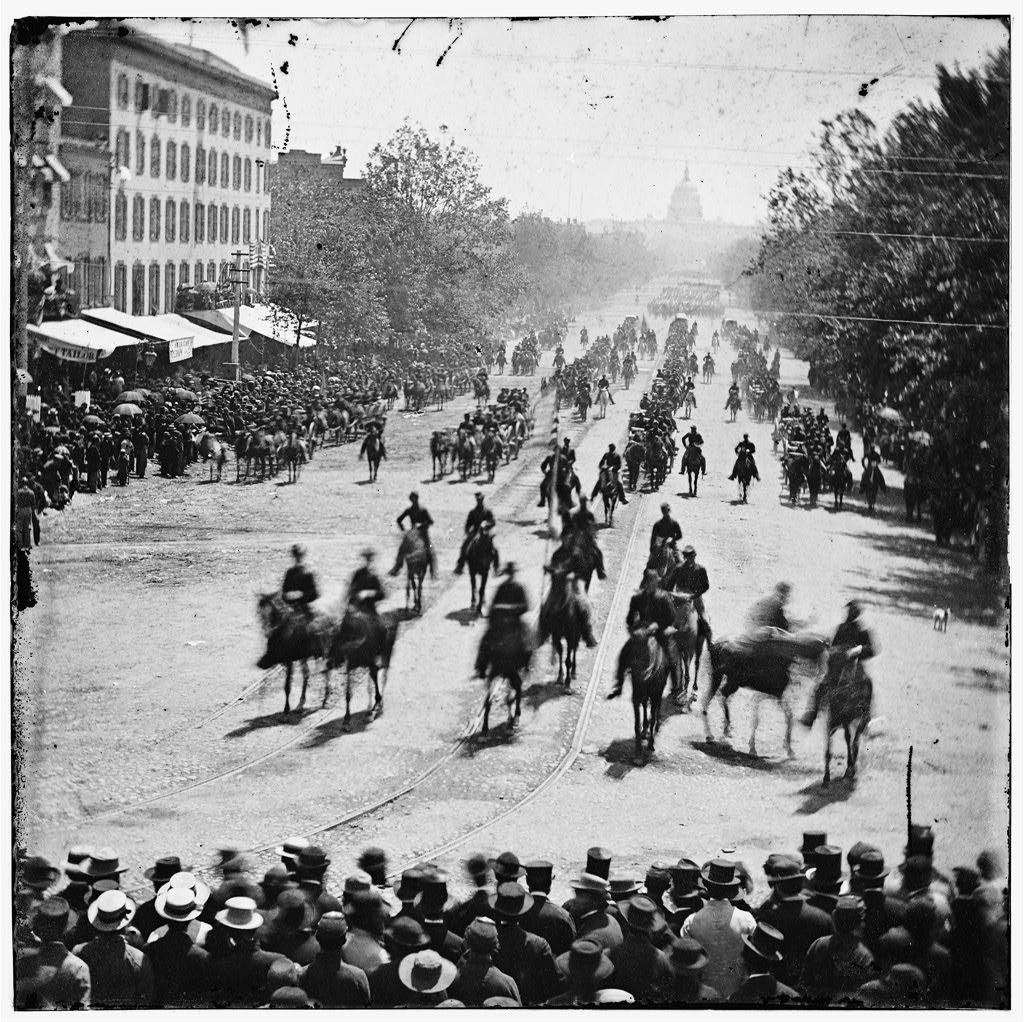

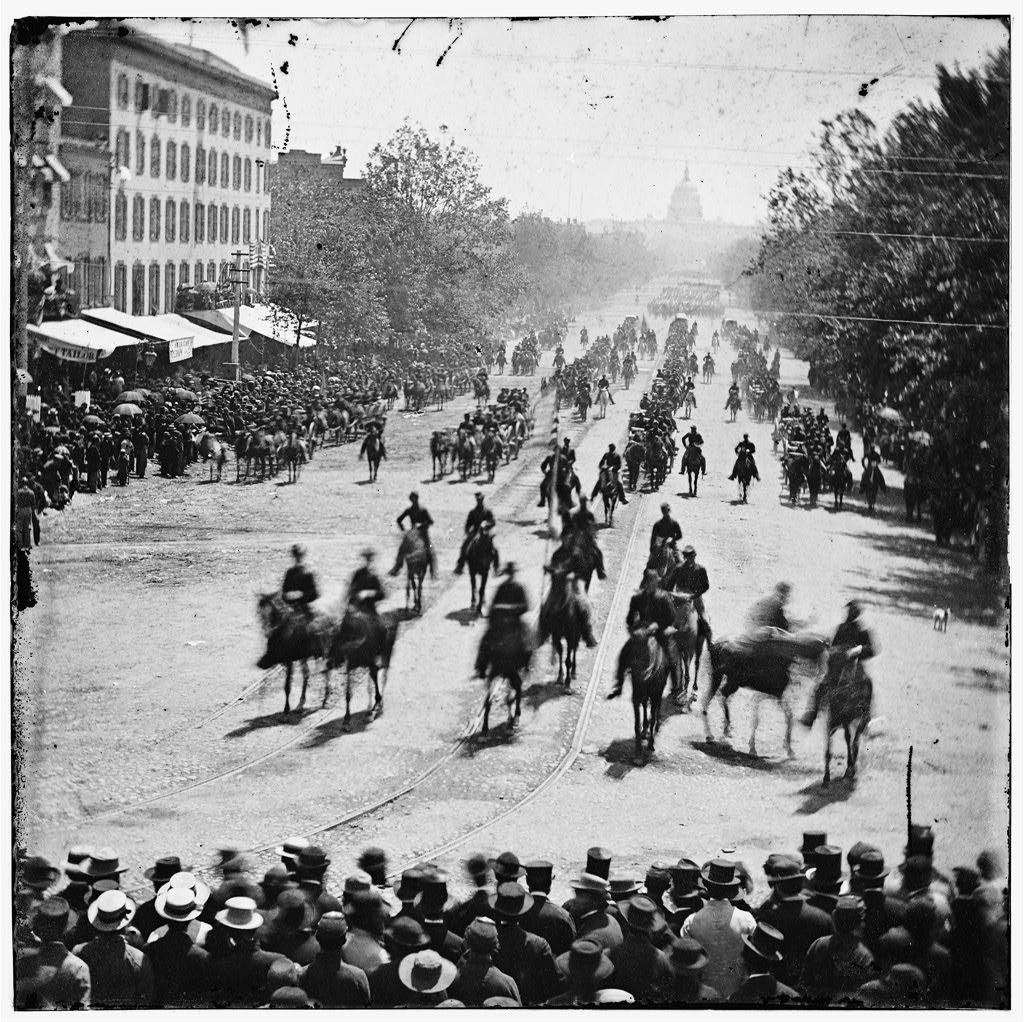

Grand Review of the Armies

On May 9, 1865, the new president,

On May 9, 1865, the new president, Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a De ...

, declared that the rebellion had virtually ended, and he planned with government authorities a formal review to honor the victorious troops. One of his side goals was to change the mood of the capital, which was still in mourning since the assassination. Three of the leading Union armies were close enough to travel to Washington to participate in the procession: the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confede ...

, the Army of the Tennessee

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

, and the Army of Georgia. Officers in the three armies who had not seen one another for some time communed and renewed acquaintances, and at times, infantrymen engaged in verbal sparring and some fisticuffs in the town's taverns and bars over the army that was superior.

The Army of the Potomac was the first to parade through the city, on May 23, in a procession that stretched for seven miles. The mood in Washington was now one of gaiety and celebration, and the crowds and soldiers frequently engaged in singing patriotic songs as column passed the reviewing stand in front of the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

, where Johnson, General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

, senior military leaders, the Cabinet, and leading government officials awaited.

On the following day, William T. Sherman

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

led the 65,000 men of the Army of the Tennessee and the Army of Georgia along Washington's streets past the cheering crowds. Within a week after the celebrations, both armies were disbanded, and many of the volunteer regiments and batteries were sent home to be mustered out of the army.

Notable leaders from Washington, D.C.

The District of Columbia, including Washington and the adjoining Georgetown, was the birthplace of several Union army generals and naval admirals as well as a leading Confederate commander.John Rodgers Meigs

John Rodgers Meigs (February 9, 1842 – October 3, 1864) was an officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He was the son of Brigadier General Montgomery C. Meigs, the Quartermaster General of the United States Army. He participated ...

(whose death sparked a significant controversy throughout the North), and Confederate brigade commander Richard Hanson Weightman.

See also

* History of Washington, D.C. *Civil War Defenses of Washington

The Civil War Defenses of Washington were a group of Union Army fortifications that protected the federal capital city, Washington, D.C., from invasion by the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War (see Washington, D.C., in the Am ...

* Bibliography of the American Civil War

The American Civil War bibliography comprises books that deal in large part with the American Civil War. There are over 60,000 books on the war, with more appearing each month. Authors James Lincoln Collier and Christopher Collier stated in 2012, ...

* Bibliography of Abraham Lincoln

This bibliography of Abraham Lincoln is a comprehensive list of written and published works about or by Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States. In terms of primary sources containing Lincoln's letters and writings, scholars rely ...

* Bibliography of Ulysses S. Grant

* Harewood General Hospital

Footnotes

Notes

Data provided by Until 1890, the U.S. Census Bureau counted the City of Washington, Georgetown, and unincorporated Washington County as three separate areas. The data provided in this article from before 1890 is calculated as if the District of Columbia were a single municipality as it is today. To view the population data for each specific area prior to 1890 see:References

* Catton, Bruce, ''Army of the Potomac: Mr. Lincoln's Army'', Doubleday and Company, 1961 * *Eicher, John H., and Eicher, David J., ''Civil War High Commands'', Stanford University Press, 2001, . *Furgurson, Ernest B., ''Freedom Rising : Washington In The Civil War'', New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004. .NPS description of defenses

* Wert, Jeffry D., ''General James Longstreet: The Confederacy's Most Controversial Soldier: A Biography'', Simon & Schuster, 1993, . *

External links

Washington, D.C. defenses

National Park Service

Civil War Washington

Further reading

*Laas, Virginia Jeans, ed., ''Wartime Washington: The Civil War Letters of Elizabeth Blair Lee'', University of Illinois Press, 1999. . * Leech, Margaret, ''Reveille in Washington: 1860–1865'', Harper and Brothers, 1941. *Leepson, Marc, ''Desperate Engagement: How a Little-Known Civil War Battle Saved Washington, D.C., and Changed The Course Of American History'', Thomas Dunne Books, 2007. . {{DC year nav 1860s in the United States Washington, D.C. American Civil War by state