Warsaw Concentration Camp on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Warsaw concentration camp (; see other names) was a

During the first nine months, the Warsaw concentration camp functioned in its own right. At this time it carried the official name of Waffen-SS Konzentrationslager Warschau (often referred to as KL Warschau for short in Nazi documents and in Polish scholarship, or, in most contemporary German-language works, KZ Warschau). In May 1944, the KL Warschau became a branch of

During the first nine months, the Warsaw concentration camp functioned in its own right. At this time it carried the official name of Waffen-SS Konzentrationslager Warschau (often referred to as KL Warschau for short in Nazi documents and in Polish scholarship, or, in most contemporary German-language works, KZ Warschau). In May 1944, the KL Warschau became a branch of

According to

According to

The camp was surrounded by high walls guarded by watchtowers. The main entrance was located at what was then Gęsia Street 24. The former military prison and ''Judenrat'' seat, at what is today 17a, served as a

The camp was surrounded by high walls guarded by watchtowers. The main entrance was located at what was then Gęsia Street 24. The former military prison and ''Judenrat'' seat, at what is today 17a, served as a

The exact number of prisoners who went through KL Warschau remains difficult to ascertain, as witness and expert estimates vary from 1,500 to 40,000. As Gabriel N. Finder noted, the Warsaw concentration camp played a minor role in the

The exact number of prisoners who went through KL Warschau remains difficult to ascertain, as witness and expert estimates vary from 1,500 to 40,000. As Gabriel N. Finder noted, the Warsaw concentration camp played a minor role in the

KL Warschau was attacked on 5 August at 10:00, when Ryszard Białous "Jerzy", Zośka's commander, and

KL Warschau was attacked on 5 August at 10:00, when Ryszard Białous "Jerzy", Zośka's commander, and

, Yad Vashem Those released were mostly Hungarian (200-250 people) and Greek Jews, with some Czechoslovakians and Dutch Jews, who knew very little Polish. It is known that only 89 people among the liberated had been Polish citizens, and historians have only been able to identify 73 prisoners by name. The Warsaw concentration camp was the only German concentration camp in Poland that was not liberated by main Allied troops, but by resistance fighters. The vast majority of released Jewish prisoners swiftly took part in the uprising, which Gabriel Finder attributes to an informal political group, which he says prevented the camp's inhabitants from moral deterioration. Some of them were fighting along with other soldiers, but most, given their lack of combat experience, were helping with transport and provisioning issues, rescuing those under ruins as well as extinguishing fires. Morale among Jewish fighters was hurt by displays of

Despite the availability of reliable information about the Warsaw concentration camp, in the 1980s a since-discredited legend or

Despite the availability of reliable information about the Warsaw concentration camp, in the 1980s a since-discredited legend or

Probably in the 1950s, a Tchorek plaque, which said that "in 1943-1944, Polish patriots were repeatedly shot to death and burnt by the Hitlerites in this building", was installed on a wall of the burnt-out Wołyń Caserns, specifically on the east wall, facing Zamenhof Street. The plaque was lost in 1965, when Gęsiówka was demolished. Bogusław Kopka says, though, that during his visit to Warsaw in 1959,

Probably in the 1950s, a Tchorek plaque, which said that "in 1943-1944, Polish patriots were repeatedly shot to death and burnt by the Hitlerites in this building", was installed on a wall of the burnt-out Wołyń Caserns, specifically on the east wall, facing Zamenhof Street. The plaque was lost in 1965, when Gęsiówka was demolished. Bogusław Kopka says, though, that during his visit to Warsaw in 1959,

File:„Gęsiówka” commemorative plaque at Anielewicza Street in Warsaw 01.jpg, alt=Official commemorative site of the Warsaw concentration camp. The plaque in English reads: "On 5 August 1944, 'Zośka', the scouts' battalion of the 'Radosław' unit Armia Krajowa captured the German concentration camp 'Gęsiówka' and liberated 348 Jewish prisoners - citizens of various European countries, many of whom later fought and fell in the Warsaw Uprising", Official commemorative site of the Warsaw concentration camp, on the corner of Anielewicza and Okopowa street, near the camp's south-west corner.

File:KL Warschau commemorative plaque at the Museum of the Prison Pawiak.jpg, alt=A commemorative plaque near Pawiak Prison (in Polish). It says: "In honour of the victims of the German concentration camp KL Warschau - inhabitants of Warsaw - the city that was never subdued. Warsaw 2013", Commemorative plaque near

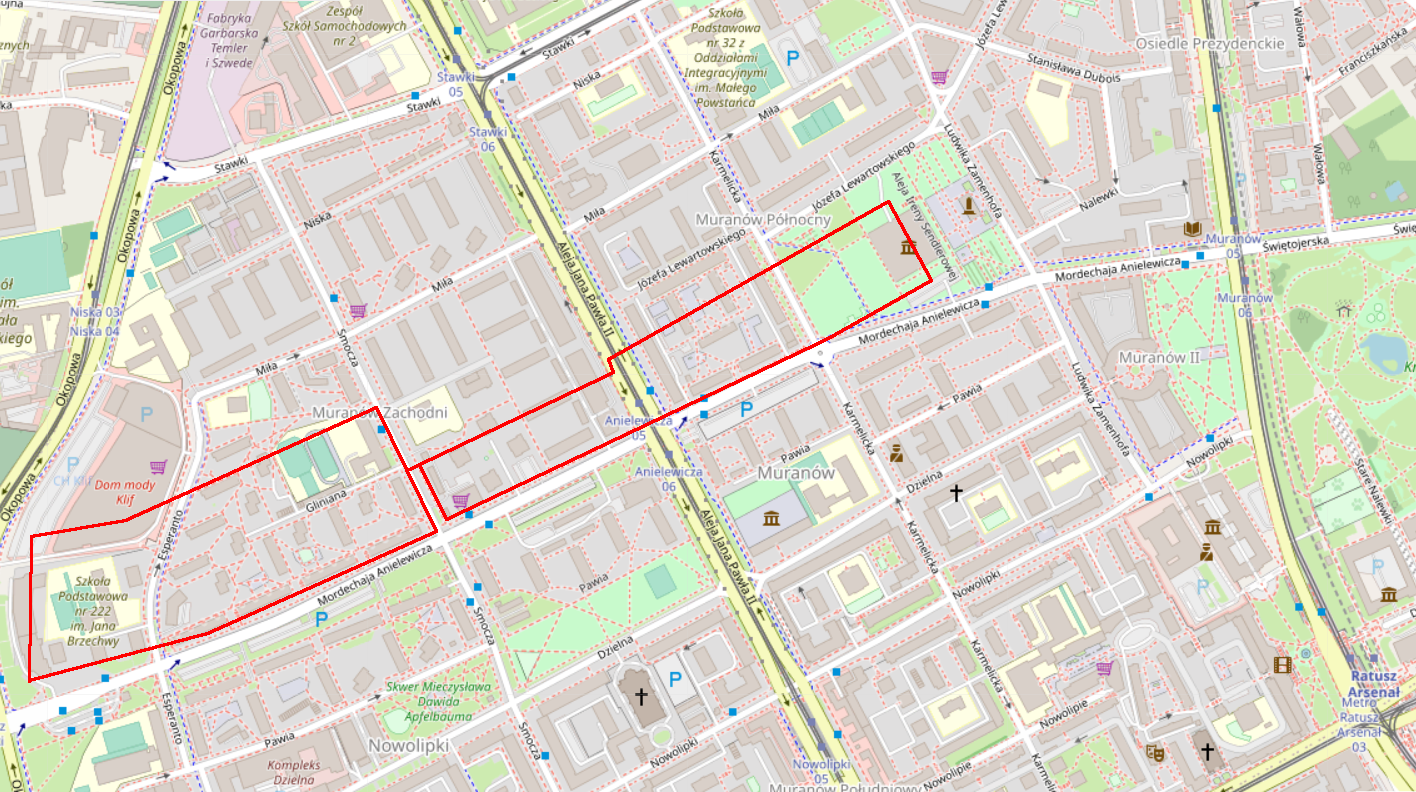

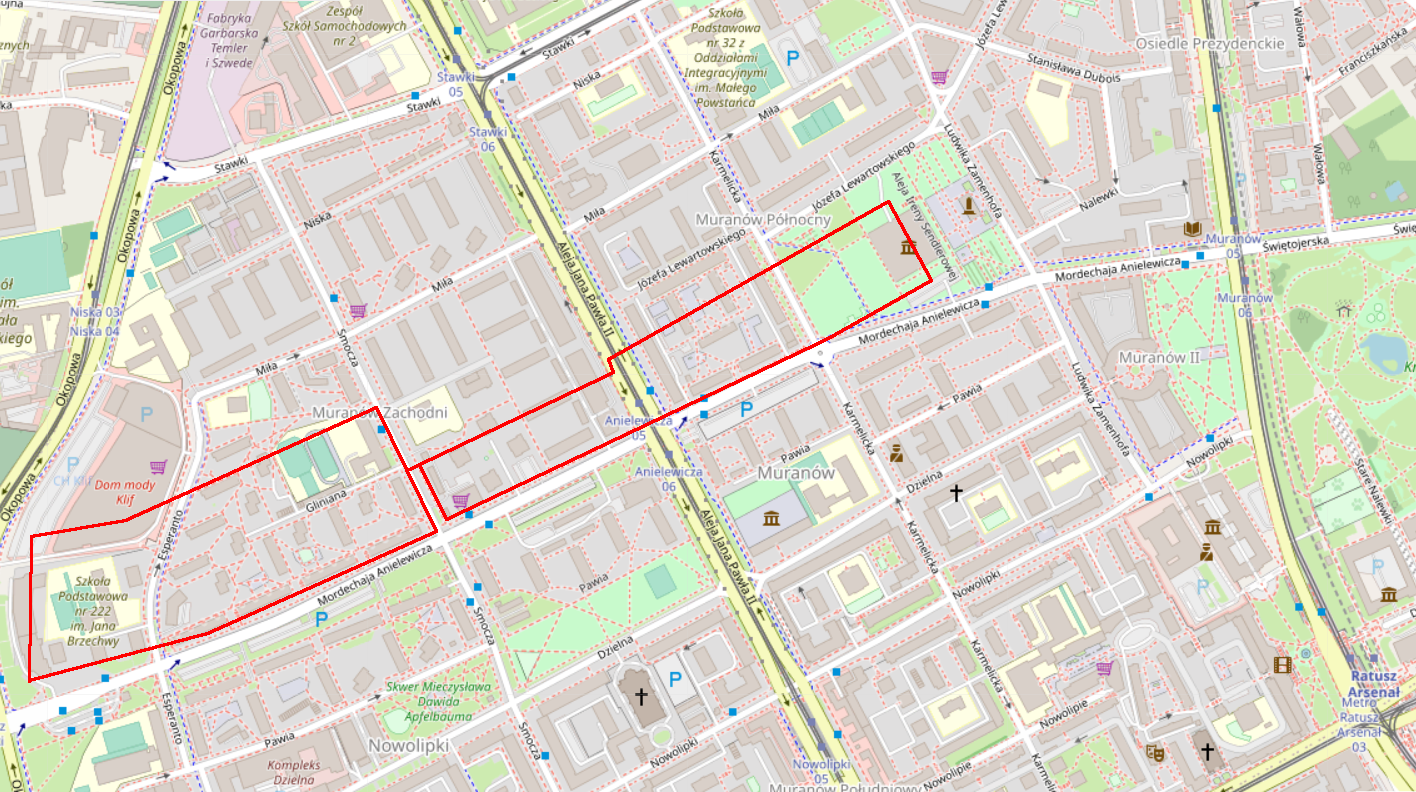

Scheme of the camppartially superimposed on current layout of the streets (in Polish)

A tool

comparing 1944 aerial photographs of Warsaw with today's satellite imagery or

Photograph of the informal commemorative plaque in ''Lasek na Kole''

as taken in 2020

Collection of materials related to the Warsaw concentration camp (particularly related to Kopka's book and controversy about Trzcińska's findings), in Polish

{{authority control 1943 in Poland 1944 in Poland 1944 disestablishments Warsaw Ghetto Nazi concentration camps in Poland The Holocaust in Poland Nazi war crimes in Poland Warsaw Uprising Demolished buildings and structures in Poland Pseudohistory Death conspiracy theories Conspiracy theories in Europe Conspiracy theories in Poland

German concentration camp

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps, (officially) or (more commonly). The Nazi concentration camps are distinguished from other types of Nazi camps such as forced-labor camps, as well as concen ...

in occupied Poland

' ( Norwegian: ') is a Norwegian political thriller TV series that premiered on TV2 on 5 October 2015. Based on an original idea by Jo Nesbø, the series is co-created with Karianne Lund and Erik Skjoldbjærg. Season 2 premiered on 10 Octobe ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, formed on the base of the now-nonexistent Gęsiówka

Gęsiówka () is the colloquial Polish name for a prison that once existed on ''Gęsia'' ("Goose") Street in Warsaw, Poland, and which, under German occupation during World War II, became a Nazi concentration camp.

In 1945–56 the Gęsiówka ...

prison, in what is today the Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officiall ...

neighbourhood of Muranów. It was created on the order of Reichsführer-SS

(, ) was a special title and rank that existed between the years of 1925 and 1945 for the commander of the (SS). ''Reichsführer-SS'' was a title from 1925 to 1933, and from 1934 to 1945 it was the highest rank of the SS. The longest-servi ...

Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

and operated from July 1943 to August 1944.

Located in the ruins of the Warsaw Ghetto

The Warsaw Ghetto (german: Warschauer Ghetto, officially , "Jewish Residential District in Warsaw"; pl, getto warszawskie) was the largest of the Nazi ghettos during World War II and the Holocaust. It was established in November 1940 by the G ...

, Warschau first functioned as a camp in its own right, but was demoted to a branch of the Majdanek concentration camp

Majdanek (or Lublin) was a Nazi concentration and extermination camp built and operated by the SS on the outskirts of the city of Lublin during the German occupation of Poland in World War II. It had seven gas chambers, two wooden gallows, ...

in May 1944. In late July that year, due to the Red Army approaching Warsaw, the Nazis started to evacuate the camp. Around 4,000 inmates were forced to march on foot to Kutno

Kutno is a city located in central Poland with 42,704 inhabitants (2021) and an area of . Situated in the Łódź Voivodeship since 1999, previously it was part of Płock Voivodeship (1975–1998) and it is now the capital of Kutno County.

Dur ...

, away; those who survived were then transported to Dachau

Dachau () was the first concentration camp built by Nazi Germany, opening on 22 March 1933. The camp was initially intended to intern Hitler's political opponents which consisted of: communists, social democrats, and other dissidents. It is lo ...

. On 5 August 1944, KL Warschau was captured by Battalion Zośka

Battalion Zośka (pronounced /'zɔɕ.ka/; 'Sophie' in Polish) was a Scouting battalion of the Polish resistance movement organisation - Home Army (Armia Krajowa or "AK") during World War II. It mainly consisted of members of the Szare Szeregi pa ...

during the Warsaw Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising ( pl, powstanie warszawskie; german: Warschauer Aufstand) was a major World War II operation by the Polish underground resistance to liberate Warsaw from German occupation. It occurred in the summer of 1944, and it was led ...

, liberating 348 Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

who were still left on its premises. It was the only German camp in Poland to be liberated by anti-Nazi resistance forces, rather than by Allied troops. After the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

definitively expelled the Germans from Warsaw in January 1945, the new communist administration continued to run the buildings as a forced labour camp, and then as a prison, until it was closed in 1956. All the camp's premises were demolished in 1965.

The '' Encyclopedia on Camps and Ghettos'' says that a total of 8,000 to 9,000 inmates were held there, while Bogusław Kopka Bogusław may refer to:

* Bogusław (given name)

* Bogusław, West Pomeranian Voivodeship

* Bogusław, Lublin Voivodeship

See also

* Bogusławski (disambiguation)

* Bohuslav

Bohuslav ( uk, Богуслав, yi, באָסלעוו or ''Boslov'') ...

estimates the number at at least 7,250 prisoners, all but 300 of whom were Jews from various European countries, in particular from Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Cr ...

and Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

. They were used as forced labour

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

to clean the ruins of the Warsaw Ghetto and to find and sort whatever precious items were still left on its territory, with the ultimate goal of creating a park in the former ghetto's area. The camp and adjacent ruins were also used by the German administration as a place of execution

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

, the victims being Polish political prisoners, Jews caught on the "Aryan

Aryan or Arya (, Indo-Iranian *''arya'') is a term originally used as an ethnocultural self-designation by Indo-Iranians in ancient times, in contrast to the nearby outsiders known as 'non-Aryan' (*''an-arya''). In Ancient India, the term ...

side", and generally people rounded up on Warsaw streets. About 4,000 to 5,000 prisoners died during the camp's existence, while the total number of people murdered in the camp is estimated at 20,000.

The camp, which played a comparatively minor role in the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europ ...

and thus seldom appears in mainstream historiography, has been at the centre of a conspiracy theory

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that invokes a conspiracy by sinister and powerful groups, often political in motivation, when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

*

*

*

* The term has a nega ...

, first promoted by Maria Trzcińska

Maria (Marianna) Trzcińska (22 March 1931 – 22 December 2011 in Warsaw) was a Polish judge employed for over 30 years in the People's Republic of Poland at the Chief Commission for the Investigation of Nazi Crimes in Poland (''Główna Komis ...

, a Polish judge who served for 22 years as a member of the Chief Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation

Chief Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation ( pl, Główna Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu) is a governmental agency created in 1945 in Poland. It is tasked with investigating German atrocities a ...

. The theory, refuted by mainstream historians, contends that KL Warschau was an extermination camp

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (german: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocaust. The v ...

operating a giant gas chamber

A gas chamber is an apparatus for killing humans or other animals with gas, consisting of a sealed chamber into which a poisonous or asphyxiant gas is introduced. Poisonous agents used include hydrogen cyanide and carbon monoxide.

History

...

inside a tunnel near Warszawa Zachodnia railroad station and that 200,000 mainly non-Jewish Poles were gassed there.

Name

During the first nine months, the Warsaw concentration camp functioned in its own right. At this time it carried the official name of Waffen-SS Konzentrationslager Warschau (often referred to as KL Warschau for short in Nazi documents and in Polish scholarship, or, in most contemporary German-language works, KZ Warschau). In May 1944, the KL Warschau became a branch of

During the first nine months, the Warsaw concentration camp functioned in its own right. At this time it carried the official name of Waffen-SS Konzentrationslager Warschau (often referred to as KL Warschau for short in Nazi documents and in Polish scholarship, or, in most contemporary German-language works, KZ Warschau). In May 1944, the KL Warschau became a branch of Majdanek concentration camp

Majdanek (or Lublin) was a Nazi concentration and extermination camp built and operated by the SS on the outskirts of the city of Lublin during the German occupation of Poland in World War II. It had seven gas chambers, two wooden gallows, ...

, so the camp's name changed to Waffen-SS Konzentrationslager Lublin – Arbeitslager Warschau (Waffen-SS Concentration Camp Lublin - Labour Camp Warsaw). It was also sometimes referred to in German sources as Arbeitslager Warschau.

In Polish sources, the name Gęsiówka (IPA

IPA commonly refers to:

* India pale ale, a style of beer

* International Phonetic Alphabet, a system of phonetic notation

* Isopropyl alcohol, a chemical compound

IPA may also refer to:

Organizations International

* Insolvency Practitioners A ...

: ) often appears as a name for the camp. This was due to the fact that the camp occupied the complex of (now non-existent), which were relatively well preserved after the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. The caserns, at the corner of then-existing Gęsia and Zamenhof streets, were a military prison before World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, and afterwards accommodated the central prison for the Jewish district, the , as well as the ''Judenrat

A ''Judenrat'' (, "Jewish council") was a World War II administrative agency imposed by Nazi Germany on Jewish communities across occupied Europe, principally within the Nazi ghettos. The Germans required Jews to form a ''Judenrat'' in every c ...

.'' The prison complex came to be colloquially known as "Gęsiówka" (named for Gęsia street), which nickname transferred to KL Warschau as well. Supporters of the Trzcińska's theory tend to prefer the German name, which Aleksandra Ubertowska says has to do with the name being perceived as more serious.

After World War II, the camp, although with changed purposes, was still run by Communist authorities under other names (see the relevant section

Section, Sectioning or Sectioned may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* Section (music), a complete, but not independent, musical idea

* Section (typography), a subdivision, especially of a chapter, in books and documents

** Section sig ...

for details).

Creation

According to

According to Bogusław Kopka Bogusław may refer to:

* Bogusław (given name)

* Bogusław, West Pomeranian Voivodeship

* Bogusław, Lublin Voivodeship

See also

* Bogusławski (disambiguation)

* Bohuslav

Bohuslav ( uk, Богуслав, yi, באָסלעוו or ''Boslov'') ...

, the first person behind the idea of creating a new concentration camp in Warsaw was Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

, head

A head is the part of an organism which usually includes the ears, brain, forehead, cheeks, chin, eyes, nose, and mouth, each of which aid in various sensory functions such as sight, hearing, smell, and taste. Some very simple animals ...

of the ''Schutzstaffel

The ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS; also stylized as ''ᛋᛋ'' with Armanen runes; ; "Protection Squadron") was a major paramilitary organization under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany, and later throughout German-occupied Europe ...

'' (SS), who mentioned it in a letter dated 9 October 1942. The letter informed the local posts of SS and Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

in the General Government

The General Government (german: Generalgouvernement, pl, Generalne Gubernatorstwo, uk, Генеральна губернія), also referred to as the General Governorate for the Occupied Polish Region (german: Generalgouvernement für die be ...

that all Jewish craftsmen who so far had managed to avoid deportation to the extermination camp

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (german: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocaust. The v ...

s were to be "assembled by SS-Obergruppenführer

' (, "senior group leader") was a paramilitary rank in Nazi Germany that was first created in 1932 as a rank of the ''Sturmabteilung'' (SA) and adopted by the ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) one year later. Until April 1942, it was the highest commissio ...

Krüger and SS-Obergruppenführer Pohl on the spot, i.e. in the concentration camps in Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officiall ...

and Lublin

Lublin is the ninth-largest city in Poland and the second-largest city of historical Lesser Poland. It is the capital and the center of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 336,339 (December 2021). Lublin is the largest Polish city east of ...

", of which the Lublin camp was already functioning. These were also intended to host Jewish labourers, who were supposed to be working for the weapons factories operating on-site; the production facilities, in their turn, were planned to be successively moved to concentration camps near Lublin, and then farther east. Himmler assumed that concentrating all Jewish labour in the camps controlled by the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office (SS-WVHA) would be the basis for the creation of an SS economic empire in the East. His ideas, however, were met with resistance from the military, the police and civil administration of the General Government, as well as from the Reich Ministry of Armaments and War Production

The Reich Ministry of Armaments and War Production () was established on March 17, 1940, in Nazi Germany. Its official name before September 2, 1943, was the 'Reichsministerium für Bewaffnung und Munition' ().

Its task was to improve the sup ...

and from German companies using Jewish slave labour

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to per ...

. Himmler was thus unable to bring his idea to fruition, so the concentration camp in Warsaw did not appear, nor did all factories using Jewish labour become controlled by SS.

As plans to demolish the Warsaw Ghetto

The Warsaw Ghetto (german: Warschauer Ghetto, officially , "Jewish Residential District in Warsaw"; pl, getto warszawskie) was the largest of the Nazi ghettos during World War II and the Holocaust. It was established in November 1940 by the G ...

appeared, Himmler soon returned to the idea of creating a concentration camp in Warsaw. In a letter dated 16 February 1943, addressed to SS-Obergruppenführer Oswald Pohl, head of SS-WVHA, Himmler ordered creating a concentration camp in the "Jewish district" and directed that all German-owned private enterprises operating in the Ghetto be relocated there. The camp, together with its enterprises and inhabitants, was planned to be "transported as quickly as possible to Lublin and nearby areas". On the same day, Himmler also wrote a letter to SS- Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger, Higher SS and police leader for the General Government, which demanded that the buildings of the deserted ghetto after the concentration camp was transported to Lublin be demolished. The task of demolition, it was suggested, was to be handed over to the local Jews. The idea's implementation was marred with numerous difficulties, so when the Germans decided to accelerate the deportations on 19 April, they met strong resistance from the Jews, who began the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. The concentration camp, again, failed to materialise, and only part of the enterprises, together with some of the Jews, were evacuated to the concentration camps in Majdanek, Trawniki, and Poniatowa.

The idea of the camp was revived once again after the failure of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. SS-Brigadeführer Jürgen Stroop

Jürgen Stroop (born Josef Stroop, 26 September 1895 – 6 March 1952) was a German SS commander during the Nazi era, who served as SS and Police Leader in occupied Poland and Greece. He led the suppression of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in 194 ...

, who led the efforts aimed at quashing the insurgency, proposed on 16 May 1943, the day the uprising came to an end, to convert the Pawiak prison

Pawiak () was a prison built in 1835 in Warsaw, Congress Poland.

During the January 1863 Uprising, it served as a transfer camp for Poles sentenced by Imperial Russia to deportation to Siberia.

During the World War II German occupation o ...

, used previously by the SD and the ''Sicherheitspolizei

The ''Sicherheitspolizei'' ( en, Security Police), often abbreviated as SiPo, was a term used in Germany for security police. In the Nazi era, it referred to the state political and criminal investigation security agencies. It was made up by the ...

'' (Security Police), to a concentration camp. It is suggested that by creating such a camp, the Germans wanted to destroy evidence of the crimes committed during the suppression of the uprising as well as to enrich themselves by the loot that would be collected in the rubble by slave labourers. Himmler agreed to the proposal and issued the order, which read:

Eventually, Pawiak's status as a prison did not change, but the concentration camp was created on nearby Gęsia street, which was also located inside the Ghetto walls, partially because it was among the only buildings left intact in the area previously occupied by the Ghetto. In addition to that, Bogusław Kopka argues that this position was chosen due to the fact that it was in a deserted area with restricted access to civilians. Another advantage was the camp's proximity to the warehouses at ''Umschlagplatz

''Umschlagplatz'' (german: collection point or reloading point) was the term used during The Holocaust to denote the holding areas adjacent to railway stations in occupied Poland where Jews from ghettos were assembled for deportation to Nazi ...

'' as well as German militarised units: an SS outpost on street, a strong German army command at street and the staff of the Pawiak prison, all of whom could be quickly dispatched in case of mutiny.

On 19 July 1943, the first 300 prisoners, who were German and predominantly criminals, were transported from Buchenwald concentration camp

Buchenwald (; literally 'beech forest') was a Nazi concentration camp established on hill near Weimar, Germany, in July 1937. It was one of the first and the largest of the concentration camps within Germany's 1937 borders. Many actual or su ...

. This date is considered to be the day when KL Warschau started operation.

Description

Location and facilities

The Warsaw concentration camp was created inside a closed and deserted zone of the former ghetto, which was surrounded by walls regularly patrolled by German guards and the police. Gęsiówka, a former military prison, and spaces along Gęsia Street were adapted for the purposes of the camp. Since none of the buildings in KL Warschau have survived, the camp's general appearance and facilities can only be deduced from witness testimony, aerial photography, and photos made during exhumations and after the camp's liberation. According to the evidence, KL Warschau was divided into two parts. The first, called ''Lager I'' and also known as "the old camp", was located between what is now and , and comprised Gęsiówka proper (the camp's easternmost part) and wooden barracks erected during the initial months of the camp's operation. The camp's second part, between Smocza and Okopowa Streets, called ''Lager II'' or "the new camp", contained brick barracks. In total, 21 barracks were built, each around long with a capacity of 600 inmates. The camp was surrounded by high walls guarded by watchtowers. The main entrance was located at what was then Gęsia Street 24. The former military prison and ''Judenrat'' seat, at what is today 17a, served as a

The camp was surrounded by high walls guarded by watchtowers. The main entrance was located at what was then Gęsia Street 24. The former military prison and ''Judenrat'' seat, at what is today 17a, served as a crematorium

A crematorium or crematory is a venue for the cremation of the dead. Modern crematoria contain at least one cremator (also known as a crematory, retort or cremation chamber), a purpose-built furnace. In some countries a crematorium can also b ...

, where bodies of dead inmates and executed civilians from outside the camp were incinerated

Incineration is a waste treatment process that involves the combustion of substances contained in waste materials. Industrial plants for waste incineration are commonly referred to as waste-to-energy facilities. Incineration and other high ...

. The Germans also started building two other cremation sites, but did not manage to open them before they evacuated the camp; even the one that existed was not operated in the camp's final days. In addition to that, one of Gęsiówka's buildings was used as a torture room, while a prison yard came to be an SS officers' mess

The mess (also called a mess deck aboard ships) is a designated area where military personnel socialize, eat and (in some cases) live. The term is also used to indicate the groups of military personnel who belong to separate messes, such as the o ...

. A bathhouse was built in late 1943 and early 1944, and bunkers were also available on-site. By February 1944 the camp's infrastructure was in an advanced stage of completion, with 90% of ''Lager I'' finished and 75% of ''Lager II'', (Berenstein gives figures of 95% and 60%, respectively) but due to the recurring typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure. ...

epidemic, which decimated the population and forced the camp's administration to quarantine

A quarantine is a restriction on the movement of people, animals and goods which is intended to prevent the spread of disease or pests. It is often used in connection to disease and illness, preventing the movement of those who may have been ...

the inmates twice (in January and February 1944, see below

Below may refer to:

*Earth

* Ground (disambiguation)

*Soil

*Floor

* Bottom (disambiguation)

*Less than

*Temperatures below freezing

*Hell or underworld

People with the surname

*Ernst von Below (1863–1955), German World War I general

*Fred Below ...

, and again in April and May), the camp was only completed in June 1944.

Personnel

Initially, about 380 SS soldiers were maintaining the concentration camp, approximately the size of acompany

A company, abbreviated as co., is a legal entity representing an association of people, whether natural, legal or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common purpose and unite to achieve specific, declared ...

. The number of SS guards was relatively low, as the former ghetto, itself a closed zone, was surrounded by patrolled walls, and due to the fact that the prisoner functionaries were Germans from the initial transport and were thus delegated much more power than was usual for their counterparts in other camps. The original SS unit was gathered from various other camps, including the Trawniki concentration camp and the Sachsenhausen concentration camp

Sachsenhausen () or Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg was a German Nazi concentration camp in Oranienburg, Germany, used from 1936 until April 1945, shortly before the defeat of Nazi Germany in May later that year. It mainly held political prisoner ...

. Following the attachment to Majdanek in May 1944, they were replaced with SS personnel from Lublin, and the guard was reduced to 259 people. The leadership positions were occupied by high- and middle-ranking SS members who were pre-war Third Reich

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

citizens (''Reichsdeutsche

', literally translated "Germans of the ", is an archaic term for those ethnic Germans who resided within the German state that was founded in 1871. In contemporary usage, it referred to German citizens, the word signifying people from the Germ ...

''), while the rank-and-file were usually recruited among the ''Volksdeutsche

In Nazi German terminology, ''Volksdeutsche'' () were "people whose language and culture had German origins but who did not hold German citizenship". The term is the nominalised plural of ''volksdeutsch'', with ''Volksdeutsche'' denoting a sing ...

'', mainly from Southeast Europe

Southeast Europe or Southeastern Europe (SEE) is a geographical subregion of Europe, consisting primarily of the Balkans. Sovereign states and territories that are included in the region are Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia (a ...

but also from other areas.

In comparison with other concentration camps, KL Warschau had a less sophisticated internal structure. Bogusław Kopka writes that the camp lacked the political department (''Politische Abteilung

The ''Politische Abteilung'' ("Political Department"), also called the "concentration camp Gestapo," was one of the five departments of a Nazi concentration camp set up by the Concentration Camps Inspectorate (CCI) to operate the camps. An outpost ...

''), and some other positions remained unoccupied; though the Institute of National Remembrance

The Institute of National Remembrance – Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation ( pl, Instytut Pamięci Narodowej – Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu, abbreviated IPN) is a Polish state resea ...

's report on the investigation of the crimes committed in KL Warschau notes that the ''Politische Abteilung'' did exist, but it was directly subordinate to the commandant of ''Sicherheitsdienst

' (, ''Security Service''), full title ' (Security Service of the '' Reichsführer-SS''), or SD, was the intelligence agency of the SS and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany. Established in 1931, the SD was the first Nazi intelligence organization ...

'' and ''Sicherheitspolizei

The ''Sicherheitspolizei'' ( en, Security Police), often abbreviated as SiPo, was a term used in Germany for security police. In the Nazi era, it referred to the state political and criminal investigation security agencies. It was made up by the ...

'' in Warsaw, instead of being the main department of the camp's administration. Among the 208 identified members of the camp's administration, SS- Karl Leuckel was the director of the administrative department, SS- Oberscharführer was the '' Rapportführer'' and the person responsible for prisoner work management, while SS- and SS- were camp doctors. The camp's staff was subordinate to SS-WVHA, but it also was obliged to cooperate closely with the SS and police leader for the Warsaw District

Warsaw District was one of the first four Nazi districts of the General Governorate region of German-occupied Poland during World War II, along with Lublin District, Radom District, and Kraków District. It was bordered on the north by Regierungsb ...

due to an agreement reached between the two SS institutions. The coordination was particularly strong during the pacification that happened at the turn of 1943/44, which was targeted at the Polish population of the capital.

There were three concentration camp commandants () in the course of the camp's history:

* SS-Obersturmbannführer

__NOTOC__

''Obersturmbannführer'' (Senior Assault-unit Leader; ; short: ''Ostubaf'') was a paramilitary rank in the German Nazi Party (NSDAP) which was used by the SA ('' Sturmabteilung'') and the SS (''Schutzstaffel''). The rank of ''Oberstu ...

Wilhelm Göcke Wilhelm Göcke (12 February 1898, Schwelm, German Empire – 20 October 1944, Fontana Liri, Italy) was an ''SS-Standartenführer'', ''SS-Obersturmbannführer der Reserve der Waffen-SS'' and a commandant of Warsaw concentration camp and the Kovno ...

served until September 1943, when he was transferred to the newly created concentration camp in Kaunas, Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

;

* SS- Hauptsturmführer Nikolaus Herbet

Nikolaus Herbet (20 March 1889 – date of death unknown) was a German SS officer and the second and last commandant of Warsaw concentration camp, during the period from September 1943 to July 1944. He was preceded in this function by Wilhelm Gö ...

commanded the camp from September or October 1943 until his arrest in late April 1944;

* SS-Obersturmführer

__NOTOC__

(, ; short: ''Ostuf'') was a Nazi Germany paramilitary rank that was used in several Nazi organisations, such as the SA, SS, NSKK and the NSFK.

The rank of ''Obersturmführer'' was first created in 1932 as the result of an expa ...

Friedrich Wilhelm Ruppert was appointed in May 1944 and dismissed in late June the same year.

As for the '' Schutzhaftlagerführer'', who was simultaneously the camp director and the chief of the guards, SS-Obersturmführer served in this role from KL Warschau's creation until his arrest in late April 1944, while SS- Unterscharführer occupied the position for the remainder of the camp's existence.

The Warsaw concentration camp usually featured SS officers who were deemed to be low-value workers. The first two commandants exhibited incompetence and little interest in the functioning of the camp. Many of the ''Volksdeutsche'' were hardly able to speak German, while some were illiterate

Literacy in its broadest sense describes "particular ways of thinking about and doing reading and writing" with the purpose of understanding or expressing thoughts or ideas in written form in some specific context of use. In other words, hum ...

. Corruption

Corruption is a form of dishonesty or a criminal offense which is undertaken by a person or an organization which is entrusted in a position of authority, in order to acquire illicit benefits or abuse power for one's personal gain. Corruption m ...

was rampant and extended up to the apex of the camp's hierarchy, which Andreas Mix attributes to the fact that like the senior SS officers, the '' kapos'' were Germans, therefore, the SS officers frequently made illicit agreements with them. The irregularities were so numerous that SS authorities eventually intervened. Andreas Mix suggests that the trigger for such an intervention was an escape of a ''Reichsdeutsche'' prisoner.

In late April 1944, Commandant Nikolaus Herbet, ''Schutzhaftlagerführer'' Wilhelm Härtel as well as ''Lagerälteste

A kapo or prisoner functionary (german: Funktionshäftling) was a prisoner in a Nazi camp who was assigned by the ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) guards to supervise forced labor or carry out administrative tasks.

Also called "prisoner self-administrat ...

'' (camp supervisor) , were all arrested. The whole command of the camp was dissolved and almost all of its members were relieved of duty. By early May, the guards who were until then performing their duties in Warsaw were transported to Sachsenhausen

Sachsenhausen () or Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg was a German Nazi concentration camp in Oranienburg, Germany, used from 1936 until April 1945, shortly before the defeat of Nazi Germany in May later that year. It mainly held political prisoners ...

and were replaced by personnel delegated from Majdanek. This scandal coincided with the degradation of the status of KL Warschau to a subcamp of Majdanek on 1 May 1944, and was thus renamed "Lublin

Lublin is the ninth-largest city in Poland and the second-largest city of historical Lesser Poland. It is the capital and the center of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 336,339 (December 2021). Lublin is the largest Polish city east of ...

concentration camp – Warsaw labour camp". According to some sources, it came due to deportations of prisoners to other camps as well as the advances of the Soviet army towards the territory of the General Government. Bogusław Kopka, Andreas Mix and Paweł Wieczorek write, however, that it was the corruption scandal that was the causative agent for the change in status, though, as the former two historians say, the camp's reorganisation failed to get rid of the corruption issues.

Prisoners

General information

The trait that distinguished the Warsaw concentration camp from the other ones was that, with the exception of the initial transport of 300 Germans, the inmates were uniformlyJewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

. Additionally, KL Warschau only accepted prisoners who were previously in concentration camps under the jurisdiction of SS-WVHA; in contrast, it did not accept those prisoners who were to serve in concentration camps due to a decision of the Reich Security Main Office

The Reich Security Main Office (german: Reichssicherheitshauptamt or RSHA) was an organization under Heinrich Himmler in his dual capacity as ''Chef der Deutschen Polizei'' (Chief of German Police) and '' Reichsführer-SS'', the head of the Naz ...

(RSHA), local Security Police

Security police officers are employed by or for a governmental agency or corporations to provide security service security services to those properties.

Security police protect facilities, properties, personnel, users, visitors and enforce cer ...

outposts, or new prisoners. These were predominantly young males (under 40 years old), whom the Germans deemed to be suitable for demanding physical work. Only in the last days of the camp's existence was a group of Jewish women from the nearby Pawiak prison delivered to KL Warschau. The Nazis were trying to transport Jews from various European countries and specifically sought to exclude Polish-speaking Jews, hoping that the lack of knowledge of Polish would prevent them from communicating with the residents of Warsaw. Therefore, few Polish Jews were detained at the Warsaw concentration camp.

The first inmates, who previously were German prisoners in the Buchenwald concentration camp, arrived on 19 July 1943. Among these 300 people, 224 were professional criminals (, or for short), 41 were deemed political prisoner

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although nu ...

s, and 35 were considered " asocial". They became prisoner functionaries, such as ''kapos'' and ''Blockältester'' (block supervisors). Walter Wawrzyniak got hold of the chief position of camp supervisor (''Lagerälteste''). Most of the German ''kapo'' prisoners, in particular those imprisoned as criminals, intimidated fellow Jewish inmates and acted towards them with cruelty, seeing them as expendable; though, as Gabriel Finder argues, this was not in most cases due to inherent anti-Semitism but rather due to the fact such violence granted them survival. Unlike in most other Nazi camps, Jewish ''kapos'' were absent from the camp and there is little evidence an internal hierarchy among Jewish prisoners has ever developed.

The first transport of Jewish prisoners arrived from Auschwitz-Birkenau

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 Nazi concentration camps, concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, occupied Poland (in a portion annexed int ...

on 31 August 1943, and three subsequent ones were made up to 27 November the same year, bringing 3,683 Jews in total, according to official data. The labourers represented Jews from various countries – the most numerous were Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

Salonican Jews, but some Austrian

Austrian may refer to:

* Austrians, someone from Austria or of Austrian descent

** Someone who is considered an Austrian citizen, see Austrian nationality law

* Austrian German dialect

* Something associated with the country Austria, for example: ...

, Belgian, French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

, Dutch, German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

and even 50 Polish representatives of that religion (who only came because Germans had to meet 1,000 people transport quota) arrived to Warsaw as well. The ethnic composition changed substantially in spring 1944, when several trains from Auschwitz delivered 3,000 Hungarian Jews

The history of the Jews in Hungary dates back to at least the Kingdom of Hungary, with some records even predating the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin in 895 CE by over 600 years. Written sources prove that Jewish communities lived ...

(most of whom originally were deported from ghettos in Hungarian-occupied Carpathian Ruthenia

Carpathian Ruthenia ( rue, Карпатьска Русь, Karpat'ska Rus'; uk, Закарпаття, Zakarpattia; sk, Podkarpatská Rus; hu, Kárpátalja; ro, Transcarpatia; pl, Zakarpacie); cz, Podkarpatská Rus; german: Karpatenukrai ...

, established in the cities of Mukachevo, Uzhhorod

Uzhhorod ( uk, У́жгород, , ; ) is a city and municipality on the river Uzh in western Ukraine, at the border with Slovakia and near the border with Hungary. The city is approximately equidistant from the Baltic, the Adriatic and the ...

, Khust and Tiachiv) who became the majority in the Warsaw concentration camp in the last months of its existence.

The exact number of prisoners who went through KL Warschau remains difficult to ascertain, as witness and expert estimates vary from 1,500 to 40,000. As Gabriel N. Finder noted, the Warsaw concentration camp played a minor role in the

The exact number of prisoners who went through KL Warschau remains difficult to ascertain, as witness and expert estimates vary from 1,500 to 40,000. As Gabriel N. Finder noted, the Warsaw concentration camp played a minor role in the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

in comparison to other camps and is thus often absent from standard narratives of the period. In his entry in the ''Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos,'' he suggested that some 8,000–9,000 people were incarcerated there. Bogusław Kopka says in his monograph that at least 7,250 inmates went through the Warsaw concentration camp, including 300 German prisoner functionaries, about 3,700 Jews who arrived in 1943 and 3,000 Jews who came in 1944 from Auschwitz, in addition to 50 highly skilled Jews sent to the camp by the '' Ostbahn'' in 1943 and 200 Jews moved from the Pawiak prison. Successful escapes were rare and Jews who were caught in the attempt were hanged in front of the assembled prisoner population.

Tasks

Prisoners were tasked with constructing the concentration camp they were residing in, demolishing the remaining ruins of the ghetto, clearing of rubble and with flattening the terrain at above the previous ground level, so as to convert the former ghetto into a park as Himmler envisaged in his order from 11 June 1943. While doing that, the workers were also ordered to salvage building materials (mainly scrap metal and bricks) for the German war effort. of buildings were demolished, with some 8,105 tonnes of metal (of which about 7,300 tonnes of ferrous scrap metals and 805 tonnes of non-ferrous metals) and 34 million bricks salvaged. A separate search team was formed to find whatever precious items, such as money or jewellery, were left in the ruins; yet another team was working on the ''Umschlagplatz

''Umschlagplatz'' (german: collection point or reloading point) was the term used during The Holocaust to denote the holding areas adjacent to railway stations in occupied Poland where Jews from ghettos were assembled for deportation to Nazi ...

'' near street, where salvaged items were sorted and stored in warehouses.

Tatiana Berenstein and Adam Rutkowski estimate the value of the pre-war houses demolished at 220 million pre-war zlotys (i.e. slightly above US$800 million in 2021 dollars), but, according to Andreas Mix, the salvaged materials were only worth 5 million reichsmark

The (; sign: ℛℳ; abbreviation: RM) was the currency of Germany from 1924 until 20 June 1948 in West Germany, where it was replaced with the , and until 23 June 1948 in East Germany, where it was replaced by the East German mark. The Reich ...

s, thus, with the initial investment of 150 million Reichsmark, the camp ran at steep losses.

A couple thousand Polish civilians, who were paid, also worked in the area, as did dozens of German technicians. At one period, these people, who usually handled more sophisticated tasks, such as the maintenance of demolition machines and handling explosives, outnumbered the inmates. German constructions firms, including Berlinisches Baugeschäft (Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

), Willy Keymer (Warsaw), Merckle (Ostrów Wielkopolski

Ostrów Wielkopolski () (often abbreviated ''Ostrów Wlkp.'', formerly called simply ''Ostrów'', german: Ostrowo, Latin: ''Ostrovia'') is a city in west-central Poland with 70,982 inhabitants (2021), situated in the Greater Poland Voivodeship; ...

), and Ostdeutscher Tiefbau (Naumburg

Naumburg () is a town in (and the administrative capital of) the district Burgenlandkreis, in the state of Saxony-Anhalt, Central Germany. It has a population of around 33,000. The Naumburg Cathedral became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2018 ...

), operated there on contract and benefitted from slave labour provided by the prisoners. The Ostbahn railway company assisted them.

Conditions

The conditions in KL Warschau were extremely harsh. Prisoners' food rationing was meagre and hunger was common among the inmates, which was exacerbated by lack of food parcels from the outside, as these were not delivered to the camp. The shortages, however, were somewhat alleviated by the presence of Polish workers contracted to remove the ruins of the ghetto, as this was an opportunity for the inmates to clandestinely buy food for whatever valuables they could find in the ruins, and, in later days, when such items became scarce, for gold fillings extracted from their teeth. However, the gold contained there was also of interest of the SS guards, who strictly forbade removal of the teeth, seeking to enrich themselves by getting the precious metal after the death of the labourers. The Jews were subjected to extermination through labour. The demolition and salvage work were hard and perilous labor, carried out at a brisk pace with no regard to loss of life of the prisoners, so fatal workplace incidents were commonplace. The guards were torturing and murdering the Jews on a whim, viewing them as enemies of the state, and prisoner functionaries, particularly criminal prisoners, were hardly better in their treatment of fellow inmates.Sanitation

Sanitation refers to public health conditions related to clean drinking water and treatment and disposal of human excreta and sewage. Preventing human contact with feces is part of sanitation, as is hand washing with soap. Sanitation syste ...

was sorely lacking to the extent that hungry and drained prisoners were decimated by outbreaks of infectious diseases, and the lack of hygiene

Hygiene is a series of practices performed to preserve health.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), "Hygiene refers to conditions and practices that help to maintain health and prevent the spread of diseases." Personal hygiene refer ...

gave way to infestations of lice

Louse ( : lice) is the common name for any member of the clade Phthiraptera, which contains nearly 5,000 species of wingless parasitic insects. Phthiraptera has variously been recognized as an order, infraorder, or a parvorder, as a resul ...

and flea

Flea, the common name for the order Siphonaptera, includes 2,500 species of small flightless insects that live as external parasites of mammals and birds. Fleas live by ingesting the blood of their hosts. Adult fleas grow to about long, ...

s. In particular, a typhus epidemic in January and February 1944 decreased the prison population by two-thirds, though the sanitary situation improved somewhat by the time the leadership was changed and the camp's construction was finished. The camp infirmary, according to Felician Loth, was "a parody of a sick ward", and patients who were unable to continue work were usually killed. For these reasons, almost 75% of original prisoners have died by March 1944, reducing the camp's population to around 1,000 inmates. This prompted the Germans to supply about 3,000 Hungarian Jews from Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 Nazi concentration camps, concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, occupied Poland (in a portion annexed int ...

.

Just as the Jews in other concentration camps, the inmates in KL Warschau were forced to wear and wooden clog

Clogs are a type of footwear made in part or completely from wood. Used in many parts of the world, their forms can vary by culture, but often remained unchanged for centuries within a culture.

Traditional clogs remain in use as protective fo ...

s. The former had the Star of David

The Star of David (). is a generally recognized symbol of both Jewish identity and Judaism. Its shape is that of a hexagram: the compound of two equilateral triangles.

A derivation of the ''seal of Solomon'', which was used for decorative ...

badge sewn on it and a Latin letter marking the inmate's provenance. The newly arrived prisoners had their hair cut shortly and then underwent a procedure of bathing and disinsectisation, which, before the bathhouse was built in the camp, was happening in Pawiak prison. Prisoner functionaries, however, were treated differently – they lived in a separate barrack (with the exception of the ''Blockältester''), could wear civilian clothes, bear arms, and were even sometimes allowed to go outside the camp's premises. Jewish inmates speaking German and/or Polish also had slightly better conditions, the former because they could easily understand the guards' orders and communicate with them, while the latter could barter more efficiently with the Polish workers.

Executions

In 1943–1944, camp inmates, Polish Jews caught hiding on the "Aryan side" of Warsaw or in the ghetto's ruins, Polishpolitical prisoner

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although nu ...

s (Pawiak

Pawiak () was a prison built in 1835 in Warsaw, Congress Poland.

During the January 1863 Uprising, it served as a transfer camp for Poles sentenced by Imperial Russia to deportation to Siberia.

During the World War II German occupation o ...

inmates) and Polish hostage

A hostage is a person seized by an abductor in order to compel another party, one which places a high value on the liberty, well-being and safety of the person seized, such as a relative, employer, law enforcement or government to act, or refr ...

s captured during the street roundups ('' łapanki'') were executed in the ruins of the former ghetto, which surrounded the camp. These executions took place almost daily and in some days, dozens or even hundreds of Poles and Jews were executed there. The bodies were then burnt, first in open air pyres and later in the camp's crematorium.

The ruins of the ghetto supplanted previous execution sites, which were operating in the countryside around Warsaw, such as in Kampinos Forest

Kampinos Forest () is a large forest complex located in Masovian Voivodeship, west of Warsaw in Poland.

It covers a part of the ancient valley of the Vistula basin, between the Vistula and the Bzura rivers.

Once a forest covering 670 km2 ...

(the site of the Palmiry massacre). The proximity of the Pawiak prison and the isolation of the former ghetto from the rest of the city, made them – from the German perspective – a far more suitable place for mass killings. Members of KL Warschau personnel, along with the members of other SS and ''Ordnungspolizei

The ''Ordnungspolizei'' (), abbreviated ''Orpo'', meaning "Order Police", were the uniformed police force in Nazi Germany from 1936 to 1945. The Orpo organisation was absorbed into the Nazi monopoly on power after regional police jurisdiction ...

'' formations in Warsaw, were among the executioners. Furthermore, a special ''Sonderkommando

''Sonderkommandos'' (, ''special unit'') were work units made up of German Nazi death camp prisoners. They were composed of prisoners, usually Jews, who were forced, on threat of their own deaths, to aid with the disposal of gas chamber vi ...

'', composed of the Jewish prisoners of the KL Warschau, was used to dispose the bodies of the victims. The members of that detachment were often murdered after completing the task, too.

It is impossible to determine the exact number of victims of executions in the ruins since the documents related to the camp were destroyed during its evacuation. Bogusław Kopka and Jan Żaryn estimate that some 20,000 people died as a result of the camp's activity, of which 10,000 were Poles. The number includes prisoner deaths as well as victims of executions in and around the camp, among whom were Polish political prisoner

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although nu ...

s and Polish Jews caught hiding on the "Aryan side" of Warsaw or in the restricted zone of the former Warsaw Ghetto. Kopka later clarified that 10,000 people at most could have died in the camp itself. The ''Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos'' gives a smaller estimate of 4,000-5,000 people, counting only prisoners of KL Warschau, while Vági and Kádár suggest 3,400 to 5,000 prisoners.

Evacuation and liberation

In summer 1944, as theRed Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

was approaching, the Germans decided to evacuate the prisons and camps in Warsaw. By the end of July, ''Schutzhaftlagerführer'' Heinz Villain demanded that all prisoners who would not be able to endure a march to assemble, promising the sick and exhausted that they would be transported in horse carriages. However, on 27 July, all those who appeared on the camp director's call were shot. The same day, all patients in the camp's infirmary were also killed. In total, around 400 prisoners, including at least 180 Hungarians, died due to these actions.

The evacuation of the Warsaw concentration camp started on 28 July. About 4,500 inmates were then forced to march to Kutno

Kutno is a city located in central Poland with 42,704 inhabitants (2021) and an area of . Situated in the Łódź Voivodeship since 1999, previously it was part of Płock Voivodeship (1975–1998) and it is now the capital of Kutno County.

Dur ...

, away, in sweltering heat. During the march, which lasted for three days, the prisoners were not given water nor food; the guards additionally murdered everyone who was unable to proceed or who was too slow to execute orders. Those who survived were loaded in freight carriages on 2 August, where poor conditions and the guards' cruelty added to the tally of dead prisoners. A total of 3,954 prisoners eventually arrived at the Dachau concentration camp

,

, commandant = List of commandants

, known for =

, location = Upper Bavaria, Southern Germany

, built by = Germany

, operated by = ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS)

, original use = Political prison

, construction ...

on 6 August, of which there were only 280 Greek Jews who arrived at the beginning of the camp's existence. The ''Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos'' says that at least 500 inmates died during the operation, while Kopka gives a higher estimate of approximately 2,000 prisoners. Most of the prisoners were subsequently transported to Dachau's subcamps in Mühldorf

Mühldorf am Inn (Central Bavarian: ''Muihdorf am Inn'') is a town in Bavaria, Germany, and the capital of the district Mühldorf on the river Inn. It is located at , and had a population of about 17,808 in 2005.

History

During the Middle Ag ...

, Kaufering and Allach-Karlsfeld, while a few were sent to Flossenbürg's subcamp in Leitmeritz (today's Litoměřice

Litoměřice (; german: Leitmeritz) is a town in the Ústí nad Labem Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 23,000 inhabitants. The town centre is well preserved and is protected by law as an urban monument reservation.

The town is the seat ...

in the Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast. The ...

).

The Warsaw concentration camp was still operating, however. Ninety SS personnel stayed there, as did about 400 prisoners who volunteered to stay in the camp to demolish it. Among those were about 300 original prisoners as well as dozens of Jewish prisoners of Pawiak (38-100 people, including 24 women), who were moved to KL Warschau on 28 July.

On 1 August, the Home Army

The Home Army ( pl, Armia Krajowa, abbreviated AK; ) was the dominant resistance movement in German-occupied Poland during World War II. The Home Army was formed in February 1942 from the earlier Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Armed Resistance) es ...

(AK) started an uprising against Germans in Warsaw. In the first day of fighting, the ''Kedyw

''Kedyw'' (, partial acronym of ''Kierownictwo Dywersji'' ("Directorate of Diversion") was a Polish World War II Home Army unit that conducted active and passive sabotage, propaganda and armed operations against Nazi German forces and collaborat ...

'' (sabotage command) for the Home Army

The Home Army ( pl, Armia Krajowa, abbreviated AK; ) was the dominant resistance movement in German-occupied Poland during World War II. The Home Army was formed in February 1942 from the earlier Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Armed Resistance) es ...

District of Warsaw led by Lt. "Stasinek" (son of Stanisław Sosabowski) captured Waffen-SS warehouses on Stawki street (''Umschlagplatz

''Umschlagplatz'' (german: collection point or reloading point) was the term used during The Holocaust to denote the holding areas adjacent to railway stations in occupied Poland where Jews from ghettos were assembled for deportation to Nazi ...

'') and a school on nearby street, setting free around 50 KL Warschau prisoners who were working there. By that time, the Home Army also partially controlled the area of "the new camp", located near Okopowa street. In light of these advances by AK, the concentration camp's staff and the prisoners retreated to the fortified defence positions in "the old camp".

In the following few days, the patrol of the insurgent forces made several incursions into KL Warschau, with little success. Meanwhile, Cpt.

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

"Jan", head of the , asked his superior, Lt. Col.

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colonel. ...

Jan Mazurkiewicz "Radosław", to storm the buildings of Gęsiówka. Control over the concentration camp's area was important from a tactical standpoint, as the Home Army could gain control over the road leading to the Old Town

In a city or town, the old town is its historic or original core. Although the city is usually larger in its present form, many cities have redesignated this part of the city to commemorate its origins after thorough renovations. There are ma ...

via the ghetto's ruins, while also serving a humanitarian purpose of liberating the prisoners, who could be murdered. Mazurkiewicz eventually agreed, and according to the plan, scout Battalion Zośka

Battalion Zośka (pronounced /'zɔɕ.ka/; 'Sophie' in Polish) was a Scouting battalion of the Polish resistance movement organisation - Home Army (Armia Krajowa or "AK") during World War II. It mainly consisted of members of the Szare Szeregi pa ...

was handed the task of capturing the concentration camp's premises.

KL Warschau was attacked on 5 August at 10:00, when Ryszard Białous "Jerzy", Zośka's commander, and

KL Warschau was attacked on 5 August at 10:00, when Ryszard Białous "Jerzy", Zośka's commander, and Wacław Micuta

Wacław Micuta (pseudonym ''Wacek''; Petrograd, Russia, 6 December 1915 – 21 September 2008, Geneva, Switzerland) was a Polish economist, World War II veteran, and United Nations functionary.

He took part in the September 1939 defense of Pola ...

, who commanded one of its platoons, started the offensive. The military advantage was on the Polish side due to their prior capture and usage of a Panther tank

The Panther tank, officially ''Panzerkampfwagen V Panther'' (abbreviated PzKpfw V) with Sonderkraftfahrzeug, ordnance inventory designation: ''Sd.Kfz.'' 171, is a German medium tank of World War II. It was used on the Eastern Front (World War ...

, which destroyed the camp's watchtowers and bunkers. The German defence eventually collapsed and SS personnel hid in the Pawiak prison walls. Battalion Zośka's losses were rather small — one person was killed in action, another died of wounds and one person was wounded in action

Wounded in Action (WIA) describes combatants who have been wounded while fighting in a combat zone during wartime, but have not been killed. Typically, it implies that they are temporarily or permanently incapable of bearing arms or continuing ...

but survived; German losses are unknown but were presumably larger. The Home Army thus liberated 348 Jews, among which 24 were women.Clearing the Ruins of the Ghetto, Yad Vashem Those released were mostly Hungarian (200-250 people) and Greek Jews, with some Czechoslovakians and Dutch Jews, who knew very little Polish. It is known that only 89 people among the liberated had been Polish citizens, and historians have only been able to identify 73 prisoners by name. The Warsaw concentration camp was the only German concentration camp in Poland that was not liberated by main Allied troops, but by resistance fighters. The vast majority of released Jewish prisoners swiftly took part in the uprising, which Gabriel Finder attributes to an informal political group, which he says prevented the camp's inhabitants from moral deterioration. Some of them were fighting along with other soldiers, but most, given their lack of combat experience, were helping with transport and provisioning issues, rescuing those under ruins as well as extinguishing fires. Morale among Jewish fighters was hurt by displays of

antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

, with several former Jewish prisoners in combat units killed by antisemitic Poles, in particular those associated with the National Armed Forces

National Armed Forces (NSZ; ''Polish:'' Narodowe Siły Zbrojne) was a Polish right-wing underground military organization of the National Democracy operating from 1942. During World War II, NSZ troops fought against Nazi Germany and communist ...

. After the defeat of the uprising, the survivors fled or hid in bunkers. There were as few as 200 Jewish survivors (former prisoners as well as Jews who were hiding on the "Aryan" side) on 17 January 1945, on which date the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

.

Postwar

After the retreat of the German forces from Warsaw, the former Nazi camp was first operated by the SovietNKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

for German prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

, as well as for the soldiers of the Home Army loyal to the Polish government-in-exile

The Polish government-in-exile, officially known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile ( pl, Rząd Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej na uchodźstwie), was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Pola ...

and other persons suspected of opposing the Soviet occupation. As in the case of the German period, the prisoners were held in poor conditions and it is probable that numerous executions were taking place in the camp.

The camp was then turned over to the Polish Ministry of Public Security (MBP) in mid-1945, when it became known as the Central Labour Camp for Warsaw's Reconstruction () and whose prisoners were used for construction and demolition works in the capital. Most of the prisoners of war were released in 1948 and 1949, and in November 1949 the labour camp was converted to a prison. The facility, which became known under two names: Central Prison — Labour Centre in Warsaw () or Central Prison Warsaw II Gęsiówka (), did not ''de facto'' change its purpose, as the inmates were still producing building materials for Warsaw's reconstruction, and it still used forced labour, but instead of prisoners of war, common criminals and people accused by the of economic wrongdoings were sent there. According to Bogusław Kopka, 1,800 people died in the postwar prison; though an estimate of 1,180 victims also appears in the literature. The fact that the former Nazi camp was taken and run by the communist authorities was the main reason why the Chief Commission for the Investigation of German Crimes in Poland ceased its investigation into its history in 1947.

The prison was closed in 1956 and was demolished in 1965. No element of the Nazi camp was preserved. As of 2022, the site is occupied by a garden square, residential buildings, and the building of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews

POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews ( pl, Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich) is a museum on the site of the former Warsaw Ghetto. The Hebrew word ''Polin'' in the museum's English name means either "Poland" or "rest here" and relates to a ...

.

Inquiries

It did not take long for the newly established Communist government in Poland to start analysing the events that happened in the camp's history. Already in May 1945, the Warsaw Circuit Commission for the Investigation of German Crimes in Poland launched a formal inquiry into the crimes committed in the Warsaw concentration camp. The premises were inspected by prosecutors several times, which yielded rich photographic documentation of the camp's buildings. On 15–25 September 1946, a total of 2180 kg of human corpses was exhumed and analysed (the corpses were then buried again in ); however, the exhumations did not cover the whole territory of the camp. In 1947, the inquiry was halted for the first time due to political considerations, as the former concentration camp had previously been taken over by the Ministry of Public Security, which converted it to a labour camp. It was only in 1974 that the investigation was continued on the request of theCentral Office of the State Justice Administrations for the Investigation of National Socialist Crimes The Central Office of the State Justice Administrations for the Investigation of National Socialist Crimes (german: Zentrale Stelle der Landesjustizverwaltungen zur Aufklärung nationalsozialistischer Verbrechen; in short or ) is Germany's main age ...

in Ludwigsburg, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

; however, after two years, it was again suspended as the prosecutors deemed it impossible to retrieve more evidence in Poland. The investigation was once again opened in 1986, only to be closed in 1996 due to the unavailability of the perpetrators for interrogation (who either went missing or were already dead). A parallel inquiry by German federal officials was also closed.

The topic of the camp returned to prominence in early 2000s, not least due to the July 2001 Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland ( Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of ...

resolution commemorating the victims of the concentration camp, so the Regional Prosecutor's Office in Warsaw decided to open the Warsaw concentration camp case once again in 2002. The case was first managed by the Institute of National Remembrance's District Commission in Warsaw, then it was transferred to Łódź

Łódź, also rendered in English as Lodz, is a city in central Poland and a former industrial centre. It is the capital of Łódź Voivodeship, and is located approximately south-west of Warsaw. The city's coat of arms is an example of ca ...

, but was promptly returned to the capital. On 23 January 2017, the case was closed for the fourth time.

Criminal responsibility of perpetrators

Following Allied victory in World War II, some people related to the Warsaw concentration camp's history were convicted in criminal or military courts. * 53 SS officers and prisoner functionaries were convicted by the judiciary of thePolish People's Republic

The Polish People's Republic ( pl, Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa, PRL) was a country in Central Europe that existed from 1947 to 1989 as the predecessor of the modern Republic of Poland. With a population of approximately 37.9 million ne ...

, who in most cases received relatively light sentences. Five ''Schutzstaffel'' officers from the camp were executed for their role in administering KL Warschau; seven died in prison and the rest was released in 1956 at the latest.

* Some members of KL Warschau staff were convicted in Dachau trials in the American zone of Allied-occupied Germany

Germany was already de facto occupied by the Allies from the real fall of Nazi Germany in World War II on 8 May 1945 to the establishment of the East Germany on 7 October 1949. The Allies (United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and Franc ...

. Wilhelm Ruppert

Friedrich Wilhelm Ruppert (February 2, 1905 – May 28, 1946) was an SS-TV Obersturmbannführer (equivalent to Lt. Col.) in charge of executions at Dachau concentration camp; he was, along with others, responsible for the executions of ...

, Alfred Kramer and , for instance, received death penalties