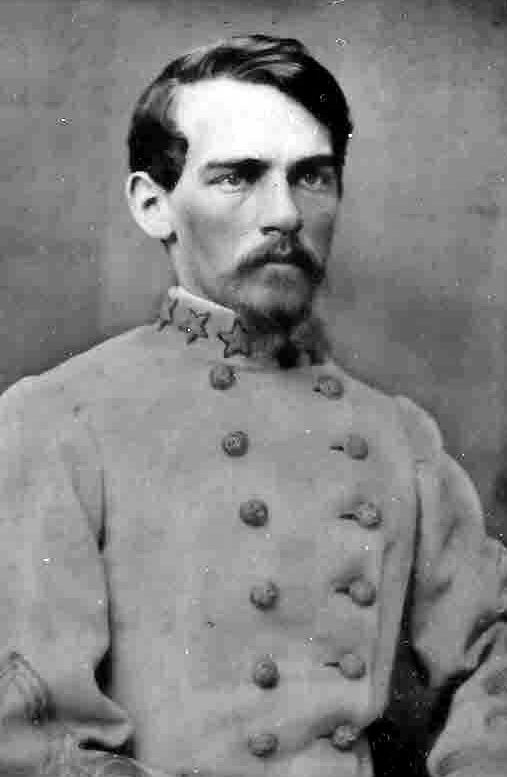

Walter H. Taylor on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Walter Herron Taylor (June 13, 1838 – March 1, 1916) was an American banker, lawyer, soldier, politician, author, and railroad executive from Norfolk, Virginia. During the

After John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859, Taylor joined a local militia company. After Virginia voters approved secession in April 1861 during the early days of the

After John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859, Taylor joined a local militia company. After Virginia voters approved secession in April 1861 during the early days of the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, he fought with the Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

, became a key aide to General Robert E. Lee and rose to the rank of Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge o ...

. After the war, Herron became a senator in the Virginia General Assembly

The Virginia General Assembly is the legislative body of the Commonwealth of Virginia, the oldest continuous law-making body in the Western Hemisphere, the first elected legislative assembly in the New World, and was established on July 30, 16 ...

, and attorney for the Norfolk and Western Railway and later the Virginian Railway

The Virginian Railway was a Class I railroad located in Virginia and West Virginia in the United States. The VGN was created to transport high quality "smokeless" bituminous coal from southern West Virginia to port at Hampton Roads.

Histor ...

.

Early life

Taylor was born on June 13, 1838, in Norfolk, Virginia. He was descended from theFirst Families of Virginia

First Families of Virginia (FFV) were those families in Colonial Virginia who were socially prominent and wealthy, but not necessarily the earliest settlers. They descended from English colonists who primarily settled at Jamestown, Williamsbur ...

, being of entirely English descent. At least one of his paternal great-grandfathers, Capt. John Calvert, had fought for the Patriot cause in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. His maternal grandfather, Dr. Jonathan Cowdery, had been taken captive by pirates in Tripoli before the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

and lived to be the eldest officer in the U.S. Navy. He was a direct descendent of Richard Taylor an English politician who sat in the House of Commons in the 1660s as well as ''his'' father also named Richard Taylor who served in the House of Commons in the 1620s. Other ancestors included colonial era migrants William Farrar and Richard Cocke as well as English colonist Adam Thoroughgood

Adam Thoroughgood horowgood'' (1604–1640) was a colonist and community leader in the Virginia Colony who helped settle the Virginia counties of Elizabeth City, Lower Norfolk and Princess Anne, the latter, known today as the independent city of ...

and his wife Sarah. Throughgood (1604–1640) rose from buying his passage across the Atlantic Ocean by becoming an indentured servant, to become an early colonial leader (and militia captain) in Norfolk County. He helped name various areas in Norfolk County, particularly near the Lynnhaven River

The Lynnhaven River is a tidal estuary located in the independent city of Virginia Beach, Virginia, in the United States, and flows into the Chesapeake Bay west of Cape Henry at Lynnhaven Inlet, beyond which is Lynnhaven Roads. It has a small, d ...

where he settled in the 17th century.

Following a local private education suitable for his class, including at Norfolk Academy, and despite his father's death, Walter Taylor went to Lexington, Virginia for higher studies. Walter H. Taylor Sr. probably owned 4 slaves during this Walter's youth. Cadet Taylor graduated from Virginia Military Institute

la, Consilio et Animis (on seal)

, mottoeng = "In peace a glorious asset, In war a tower of strength""By courage and wisdom" (on seal)

, established =

, type = Public senior military college

, accreditation = SACS

, endowment = $696.8 mill ...

(VMI) in 1857. He became a railroad clerk, and later a banker in Norfolk.

American Civil War

After John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859, Taylor joined a local militia company. After Virginia voters approved secession in April 1861 during the early days of the

After John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859, Taylor joined a local militia company. After Virginia voters approved secession in April 1861 during the early days of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, Taylor joined the Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

, as did others in his militia company and his elder brother, Richard Cornelius Taylor (1835-1917; who would become a Major before the war's end).

Walter Taylor was soon assigned to the staff of General Robert E. Lee, shortly after the General was given command of Confederate forces. Taylor became no ordinary staff officer, but effectively the chief aide-de-camp to General Lee throughout the war. Since Lee was noted for his small, over-worked staff, the exceedingly capable and tireless Taylor had many responsibilities. He wrote dispatches and orders for Lee, performed personal reconnaissance, and often carried messages in person to corps

Corps (; plural ''corps'' ; from French , from the Latin "body") is a term used for several different kinds of organization. A military innovation by Napoleon I, the formation was first named as such in 1805. The size of a corps varies great ...

and division

Division or divider may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

*Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division

Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting ...

commanders. (He verbally transmitted the famous "if practicable" order from Lee to General Richard S. Ewell below Cemetery Hill during the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the Po ...

.) Taylor greeted all people who came to see Lee, and usually decided whether they would be announced to the General. When General Lee assumed command of the Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most oft ...

in June 1862, during the Peninsula Campaign, Taylor became that army's assistant adjutant general

An adjutant general is a military chief administrative officer.

France

In Revolutionary France, the was a senior staff officer, effectively an assistant to a general officer. It was a special position for lieutenant-colonels and colonels in staf ...

. Taylor eventually attained a rank almost commensurate with his great staff responsibilities, being promoted to lieutenant colonel on December 12, 1863.

Ltc. Taylor accompanied General Lee during the surrender at Appomattox Court House. (In postbellum writings, he is generally referred to as "colonel", a customary abbreviated title.)

Personal life

Taylor's fiancée was Elizabeth Selden "Bettie" Saunders, daughter of United States Navy Captain John Loyall Saunders and Mrs. Martha Bland Selden Saunders. During the war Miss Saunders lived with the family of Lewis D. Crenshaw in Richmond, Virginia, where she worked in the Confederate Mint and for the Surgeon General in the Confederate Medical Department. In the last few days of theSiege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War. Although it is more popularly known as the Siege of Petersburg, it was not a cla ...

, as Lee and his staff realized that Petersburg was lost and Richmond should be evacuated, General Lee gave the 26-year-old Taylor special permission to go to Richmond to give Miss Saunders "the protection of his name". A messenger sent ahead to Richmond advised his bride-to-be, who made arrangements with Reverend Dr. Charles Minnigerode Charles Frederick Ernest Minnigerode (born Karl Friedrich Ernst Minnigerode, August 6, 1814 in Arnsberg - October 13, 1894 in Alexandria, Virginia) was a German-born American professor and clergyman who is credited with introducing the Christmas t ...

, the rector of St. Paul's Episcopal Church.

After midnight, in the wee hours of April 3, 1865, just before evacuating Confederates set fire to the city and looters ran wild in its streets, Taylor and Miss Saunders were married in the Crenshaw house parlor. Afterward, Lewis Crenshaw accompanied Taylor as far back toward the Confederate lines as safety permitted. One week after the surrender at Appomattox Court House, Taylor returned to Richmond with General Lee, picked up his bride, and drove her back to Norfolk in a buggy.

They would have at least two daughters and three sons who reached adulthood.

Postwar career

After the war, Taylor resumed his banking career in Norfolk, and also worked as an attorney, particularly for railroads which were rebuilding and consolidating after the war. He quickly received a pardon, then was elected to municipal offices and to theVirginia General Assembly

The Virginia General Assembly is the legislative body of the Commonwealth of Virginia, the oldest continuous law-making body in the Western Hemisphere, the first elected legislative assembly in the New World, and was established on July 30, 16 ...

as a Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

(in the same election as adopted a new state Constitution which forbad slavery). Taylor served as a State Senator from 1869 until 1873, vehemently opposing the Readjuster Party.

On April 30, 1870, General Lee paid his last visit to the Norfolk area, accompanied by his daughter, Agnes Lee. He arrived in Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

via railroad from North Carolina. Colonel Taylor met and escorted him through the waiting crowds to Norfolk, then to the Elizabeth River ferry. Lee would die less than five months later. In 1870, Taylor began his first term on the VMI Board of Visitors (serving until 1873); he would again serve on the VMI board from 1914 until his death.

In 1877, Taylor became president of the Marine Bank, where he would remain for 39 years. He later also served on the board of directors of the Norfolk and Western Railway. Near the end of the 19th century, Taylor helped develop the Ocean View area, located along the south shore of the Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the Eastern Shore of Maryland / ...

in Norfolk County. The project had been surveyed and laid out before the American Civil War by William Mahone

William Mahone (December 1, 1826October 8, 1895) was an American civil engineer, railroad executive, Confederate States Army general, and Virginia politician.

As a young man, Mahone was prominent in the building of Virginia's roads and railroa ...

, who also later became a Confederate General (serving under General Lee and then with the Readjusters whom Taylor had opposed after the war). Served by a narrow gauge railroad

A narrow-gauge railway (narrow-gauge railroad in the US) is a railway with a track gauge narrower than standard . Most narrow-gauge railways are between and .

Since narrow-gauge railways are usually built with tighter curves, smaller structur ...

from Norfolk, which operated a steam locomotive named the "Walter H. Taylor", Ocean View blossomed as both a popular resort area and streetcar suburb of the City of Norfolk, which annexed the area in 1923.

In April 1907, while Taylor was the attorney for the new Virginian Railway

The Virginian Railway was a Class I railroad located in Virginia and West Virginia in the United States. The VGN was created to transport high quality "smokeless" bituminous coal from southern West Virginia to port at Hampton Roads.

Histor ...

, then under construction, he met the founder, millionaire industrialist Henry Huttleston Rogers

Henry Huttleston Rogers (January 29, 1840 – May 19, 1909) was an American industrialist and financier. He made his fortune in the oil refining business, becoming a leader at Standard Oil. He also played a major role in numerous corporations ...

and humorist Mark Twain when they arrived in Hampton Roads aboard Rogers' steam yacht ''Kanawha''. They were in Norfolk to attend the opening ceremonies of the Jamestown Exposition

The Jamestown Exposition was one of the many world's fairs and expositions that were popular in the United States in the early part of the 20th century. Commemorating the 300th anniversary of the founding of Jamestown in the Virginia Colony, it w ...

held at Sewell's Point. According to published newspaper reports of the day, Twain drove off with Taylor in an "infernal machine," better known in modern times as an automobile.

"Lost Cause" proponent

Taylor devoted a considerable portion of his postwar years to defending General Lee's reputation (which developed into theLost Cause

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy (or simply Lost Cause) is an American pseudohistorical negationist mythology that claims the cause of the Confederate States during the American Civil War was just, heroic, and not centered on slavery. Firs ...

historiography), as well as settling controversies related to the Army of Northern Virginia. Although less vehement than the notoriously irascible former General Jubal Early

Jubal Anderson Early (November 3, 1816 – March 2, 1894) was a Virginia lawyer and politician who became a Confederate States of America, Confederate general during the American Civil War. Trained at the United States Military Academy, Early r ...

, Taylor worked with the Louisiana-based Southern Historical Society

The Southern Historical Society was an American organization founded to preserve archival materials related to the government of the Confederate States of America and to document the history of the Civil War.Association of the Army of Northern Virginia and the

Taylor, Walter H., Belmont, John S., Tower, R. Lockwood, ''Lee's Adjutant: The Wartime Letters of Colonel Walter Herron Taylor, 1862–1865'', University of South Carolina Press, 1995, . {{DEFAULTSORT:Taylor, Walter H. 1838 births 1916 deaths Confederate States Army officers 19th-century American railroad executives 20th-century American railroad executives People of Virginia in the American Civil War Virginia Military Institute alumni Virginia lawyers Military personnel from Norfolk, Virginia 19th-century American lawyers Southern Historical Society

United Confederate Veterans

The United Confederate Veterans (UCV, or simply Confederate Veterans) was an American Civil War veterans' organization headquartered in New Orleans, Louisiana. It was organized on June 10, 1889, by ex-soldiers and sailors of the Confederate Sta ...

.

Former generals from both sides of the war made Taylor an unofficial court of last resort

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

in settling disputes about their wartime reputations. Many generals petitioned him for information, so Taylor decided to write a book to set the record straight. He asked for permission from the U.S. government to view the national archives related to the Army of the Potomac and became the first Confederate granted such a privilege. Thus in 1877, he published ''Four Years with General Lee'', which contained dozens of anecdotes about the former General. Because it contained much from the National Archives, it read more like a situation report than a novel, and was not widely popular at the time. Former Confederate General James Longstreet in particular claimed that if Col. Taylor ever wrote another book about the war, he hoped it would tell the "rest of the story." (Many former Confederates vilified Longstreet for not only his actions at Gettysburg, but also his postwar accommodation with the Republicans.) Col. Taylor did write another book, ''Robert E. Lee, His Campaign in Virginia, 1861–1865'' (1906). Although it contained the same statistical information as his previous work, it read more like a novel, and quickly became a best seller.

Death and legacy

Walter H. Taylor died of cancer on March 1, 1916. Walter H. Taylor Elementary School of theNorfolk City Public Schools

The Norfolk Public Schools, also known as Norfolk City Public Schools, are the school division responsible for public education in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. ...

is named in his honor.

In popular media

Taylor is a character in the novel "The Killer Angels

''The Killer Angels'' is a 1974 historical novel by Michael Shaara that was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1975. The book depicts the three days of the Battle of Gettysburg during the American Civil War, and the days leading up to it ...

" (1974) by Michael Shaara

Michael Shaara (June 23, 1928 – May 5, 1988) was an American author of science fiction, sports fiction, and historical fiction. He was born to an Italian immigrant father (the family name was originally spelled Sciarra, which in Italian is pron ...

, which won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1975. He is portrayed by Bo Brinkman in the novel's film adaption ''Gettysburg'', and in the prequel '' Gods and Generals''.

Taylor is a character in the following alternate history novels:

*''The Guns of the South

''The Guns of the South'' is an alternate history novel set during the American Civil War by Harry Turtledove. It was released in the United States on September 22, 1992.

The story deals with a group of time-traveling white supremacist member ...

'' (1992) by Harry Turtledove

Harry Norman Turtledove (born June 14, 1949) is an American author who is best known for his work in the genres of alternate history, historical fiction, fantasy, science fiction, and mystery fiction. He is a student of history and completed hi ...

*" Gettysburg: A Novel of the Civil War" (2003), " Grant Comes East" (2004), and " Never Call Retreat" (2005) by Newt Gingrich and William R. Forstchen.

References

Works by Taylor

Taylor, Walter H., Belmont, John S., Tower, R. Lockwood, ''Lee's Adjutant: The Wartime Letters of Colonel Walter Herron Taylor, 1862–1865'', University of South Carolina Press, 1995, . {{DEFAULTSORT:Taylor, Walter H. 1838 births 1916 deaths Confederate States Army officers 19th-century American railroad executives 20th-century American railroad executives People of Virginia in the American Civil War Virginia Military Institute alumni Virginia lawyers Military personnel from Norfolk, Virginia 19th-century American lawyers Southern Historical Society