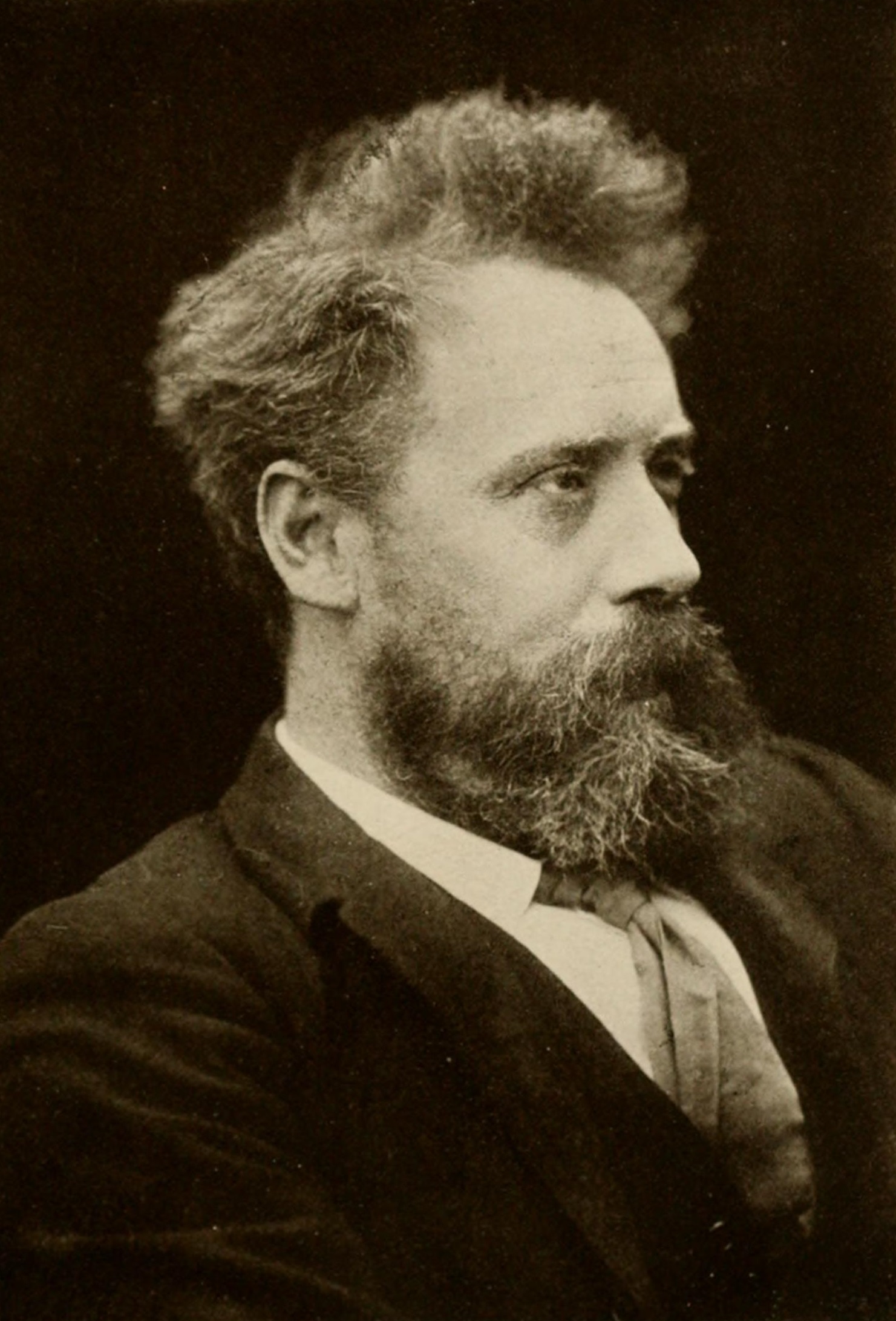

W. E. Henley on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Ernest Henley (23 August 184911 July 1903) was an English poet, writer, critic and editor. Though he wrote several books of poetry, Henley is remembered most often for his 1875 poem " Invictus". A fixture in London literary circles, the one-legged Henley might have been the inspiration for

From the age of 12, Henley had

From the age of 12, Henley had

Margaret was a sickly child, and became immortalised by

Margaret was a sickly child, and became immortalised by

accessed 9 May 2015. Unable to speak clearly, young Margaret had called her friend Barrie her "fwendy-wendy", resulting in the use of the name "Wendy" for a feminine character in the book. Margaret did not survive long enough to read the book; she died in 1894 at the age of five and was buried at the country estate of her father's friend, Henry Cust, Harry Cockayne Cust, in Cockayne Hatley, Bedfordshire. After Robert Louis Stevenson received a letter from Henley labelled "Private and Confidential" and dated 9 March 1888, in which the latter accused Stevenson's new wife Fanny of plagiarising his cousin

In 1902, Henley fell from a railway carriage. This accident caused his latent tuberculosis to flare up, and he died of it on 11 July 1903, at the age of 53, at his home in Woking, Surrey. After cremation at the local crematorium his ashes were interred in his daughter's grave in the churchyard at Cockayne Hatley in

In 1902, Henley fell from a railway carriage. This accident caused his latent tuberculosis to flare up, and he died of it on 11 July 1903, at the age of 53, at his home in Woking, Surrey. After cremation at the local crematorium his ashes were interred in his daughter's grave in the churchyard at Cockayne Hatley in

Villon's Straight Tip to All Cross Coves

' (a free translation of François Villon's ''Tout aux tavernes et aux filles'') was recited by

an

accessed 9 May 2015. with the title major work, and 16 additional poems, including a dedication to his wife (and epilogue, both penned in

accessed 9 May 2015. Quote: "Henley's 'Waiting,' from his 'In Hospital' sequence of poems far outshines his better known 'Invictus.'" * Andrzej Diniejko, 2011, "William Ernest Henley: A Biographical Sketch," at ''Victorian Web'' (online), updated 19 July 2011, se

accessed 9 May 2015. * Jerome Hamilton Buckley, 1945, ''William Ernest Henley: A Study in the Counter-Decadence of the Nineties,'' Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

''Victorian Web'' article on Henley.

* Edward H. Cohen, 1974, ''The Henley-Stevenson Quarrel,'' Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press

* John Connell, 1949, ''W. E. Henley,'' London: Constable.

* Donald Davidson, 1937, ''British Poetry of the Eighteen-Nineties,'' Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran

* Maria H. Frawley, 2004, ''Invalidism and Identity in Nineteenth-century Britain,'' IL: University of Chicago Press

* Kennedy Williamson, 1930, ''W. E. Henley. A Memoir,'' London: Harold Shaylor.

Works by or about William Ernest Henley

at HathiTrust *

Poetry Archive: 137 poems of William Ernest Henley

* " The Difference", a poem by

William Ernest Henley: Profile and Poems at Poets.org

* * William Ernest Henley Collection. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. {{DEFAULTSORT:Henley, William Ernest English literary critics English magazine editors People from Gloucester English amputees 1849 births 1903 deaths People educated at The Crypt School, Gloucester 20th-century deaths from tuberculosis English male poets 19th-century English poets 19th-century English male writers English male non-fiction writers Tuberculosis deaths in England Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as ''Treasure Island'', ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll a ...

's character Long John Silver

Long John Silver is a Character (arts), fictional character and the main antagonist in the novel ''Treasure Island'' (1883) by Robert Louis Stevenson. The most colourful and complex character in the book, he continues to appear in popular cult ...

(''Treasure Island

''Treasure Island'' (originally titled ''The Sea Cook: A Story for Boys''Hammond, J. R. 1984. "Treasure Island." In ''A Robert Louis Stevenson Companion'', Palgrave Macmillan Literary Companions. London: Palgrave Macmillan. .) is an adventure no ...

,'' 1883), while his young daughter Margaret Henley inspired J. M. Barrie

Sir James Matthew Barrie, 1st Baronet, (; 9 May 1860 19 June 1937) was a Scottish novelist and playwright, best remembered as the creator of Peter Pan. He was born and educated in Scotland and then moved to London, where he wrote several succ ...

's choice of the name Wendy for the heroine of his play ''Peter Pan

Peter Pan is a fictional character created by Scottish novelist and playwright J. M. Barrie. A free-spirited and mischievous young boy who can fly and never grows up, Peter Pan spends his never-ending childhood having adventures on the mythi ...

'' (1904).

Early life and education

Henley was born inGloucester

Gloucester ( ) is a cathedral city and the county town of Gloucestershire in the South West of England. Gloucester lies on the River Severn, between the Cotswolds to the east and the Forest of Dean to the west, east of Monmouth and east ...

on 23 August 1849, to mother, Mary Morgan, a descendant of poet and critic Joseph Warton

Joseph Warton (April 1722 – 23 February 1800) was an English academic and literary critic.

He was born in Dunsfold, Surrey, England, but his family soon moved to Hampshire, where his father, the Reverend Thomas Warton, became vicar of B ...

, and father, William, a bookseller and stationer. William Ernest was the oldest of six children, five sons and a daughter; his father died in 1868.

Henley was a pupil at the Crypt School, Gloucester

Gloucester ( ) is a cathedral city and the county town of Gloucestershire in the South West of England. Gloucester lies on the River Severn, between the Cotswolds to the east and the Forest of Dean to the west, east of Monmouth and east ...

, between 1861 and 1867. A commission had recently attempted to revive the school by securing as headmaster the brilliant and academically distinguished Thomas Edward Brown

Thomas Edward Brown (5 May 183029 October 1897), commonly referred to as T. E. Brown, was a late- Victorian scholar, schoolmaster, poet, and theologian from the Isle of Man.

Having achieved a double first at Christ Church, Oxford, and electi ...

(1830–1897). Though Brown's tenure was relatively brief (–1863), he was a "revelation" to Henley because the poet was "a man of geniusthe first I'd ever seen". After carrying on a lifelong friendship with his former headmaster, Henley penned an admiring obituary for Brown in the ''New Review'' (December 1897): "He was singularly kind to me at a moment when I needed kindness even more than I needed encouragement".John Connell, 1949, ''W. E. Henley'', London:Constable, page numbers as indicated. Nevertheless, Henley was disappointed in the school itself, considered an inferior sister to the Cathedral School

Cathedral schools began in the Early Middle Ages as centers of advanced education, some of them ultimately evolving into medieval universities. Throughout the Middle Ages and beyond, they were complemented by the monastic schools. Some of these ...

, and wrote about its shortcomings in a 1900 article in ''The Pall Mall Magazine

''The Pall Mall Magazine'' was a monthly British literary magazine published between 1893 and 1914. Begun by William Waldorf Astor as an offshoot of ''The Pall Mall Gazette'', the magazine included poetry, short stories, serialized fiction, and ge ...

''.

Much later, in 1893, Henley also received an LLD degree from the University of St Andrews

(Aien aristeuein)

, motto_lang = grc

, mottoeng = Ever to ExcelorEver to be the Best

, established =

, type = Public research university

Ancient university

, endowment ...

; however two years after that he failed to secure the position of Professor of English literature at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

.

Health issues and Long John Silver

From the age of 12, Henley had

From the age of 12, Henley had tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...

of the bone that resulted in the amputation of his left leg below the knee in 1868–69. The early years of Henley's life were punctuated by periods of extreme pain due to the draining of his tuberculosis abscesses. However, Henley's younger brother Joseph recalled how after draining his joints the young Henley would "Hop about the room, laughing loudly and playing with zest to pretend he was beyond the reach of pain". According to Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as ''Treasure Island'', ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll a ...

's letters, the idea for the character of Long John Silver

Long John Silver is a Character (arts), fictional character and the main antagonist in the novel ''Treasure Island'' (1883) by Robert Louis Stevenson. The most colourful and complex character in the book, he continues to appear in popular cult ...

was inspired by Stevenson's real-life friend Henley. In a letter to Henley after the publication of ''Treasure Island'' (1883), Stevenson wrote, "I will now make a confession: It was the sight of your maimed strength and masterfulness that begot Long John Silver ... the idea of the maimed man, ruling and dreaded by the sound, was entirely taken from you." Stevenson's stepson, Lloyd Osbourne, described Henley as "... a great, glowing, massive-shouldered fellow with a big red beard and a crutch; jovial, astoundingly clever, and with a laugh that rolled like music; he had an unimaginable fire and vitality; he swept one off one's feet."

Frequent illness often kept Henley from school, although the misfortunes of his father's business may also have contributed. In 1867, Henley passed the Oxford Local Schools Examination. Soon after passing the examination, Henley moved to London and attempted to establish himself as a journalist. His work over the next eight years was interrupted by long stays in hospitals, because his right foot had also become diseased. Henley contested the diagnosis that a second amputation was the only means to save his life, seeking treatment from the pioneering late 19th-century surgeon Joseph Lister

Joseph Lister, 1st Baron Lister, (5 April 182710 February 1912) was a British surgeon, medical scientist, experimental pathologist and a pioneer of antiseptic surgery and preventative medicine. Joseph Lister revolutionised the craft of ...

at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh

The Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, or RIE, often (but incorrectly) known as the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, or ERI, was established in 1729 and is the oldest voluntary hospital in Scotland. The new buildings of 1879 were claimed to be the largest v ...

, commencing in August 1873. Henley spent three years in hospital (1873–75), during which he was visited by the authors Leslie Stephen

Sir Leslie Stephen (28 November 1832 – 22 February 1904) was an English author, critic, historian, biographer, and mountaineer, and the father of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell.

Life

Sir Leslie Stephen came from a distinguished intellect ...

and Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as ''Treasure Island'', ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll a ...

and wrote and published the poems collected as ''In Hospital''. This also marked the beginning of a fifteen-year friendship with Stevenson.

Physical appearance

Throughout his life, the contrast between Henley's physical appearance and his mental and creative capacities struck acquaintances in completely opposite, but equally forceful ways. Recalling his old friend, Sidney Low commented, "... to me he was the startling image of Pan come to Earth and clothed—the great god Pan...with halting foot and flaming shaggy hair, and arms and shoulders huge and threatening, like those of some Faun or Satyr of the ancient woods, and the brow and eyes of the Olympians." After hearing of Henley's death on 13 July 1903, the authorWilfrid Scawen Blunt

Wilfrid Scawen Blunt (17 August 1840 – 10 September 1922), sometimes spelt Wilfred, was an English poet and writer. He and his wife Lady Anne Blunt travelled in the Middle East and were instrumental in preserving the Arabian horse bloodlines ...

recorded his physical and ideological repugnance to the late poet and editor in his diary, "He has the bodily horror of the dwarf, with the dwarf's huge bust and head and shrunken nether limbs, and he has also the dwarf malignity of tongue and defiant attitude towards the world at large. Moreover, I am quite out of sympathy with Henley's deification of brute strength and courage, things I wholly despise."

Personal life

Henley married Hannah (Anna) Johnson Boyle (1855–1925) on 22 January 1878. Born inStirling

Stirling (; sco, Stirlin; gd, Sruighlea ) is a city in central Scotland, northeast of Glasgow and north-west of Edinburgh. The market town, surrounded by rich farmland, grew up connecting the royal citadel, the medieval old town with its me ...

, she was the youngest daughter of Edward Boyle, a mechanical engineer from Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian on the southern shore of t ...

, and his wife, Mary Ann née Mackie. In the 1891 Scotland Census, William and Anna are recorded as living with their two-year-old daughter, Margaret Emma Henley (b. 1888), in Edinburgh.

Margaret was a sickly child, and became immortalised by

Margaret was a sickly child, and became immortalised by J. M. Barrie

Sir James Matthew Barrie, 1st Baronet, (; 9 May 1860 19 June 1937) was a Scottish novelist and playwright, best remembered as the creator of Peter Pan. He was born and educated in Scotland and then moved to London, where he wrote several succ ...

in his children's classic, ''Peter Pan

Peter Pan is a fictional character created by Scottish novelist and playwright J. M. Barrie. A free-spirited and mischievous young boy who can fly and never grows up, Peter Pan spends his never-ending childhood having adventures on the mythi ...

.''Christopher Winn (2012). ''I Never Knew That About England,'' London: Random House, , pp. 3–4, seaccessed 9 May 2015. Unable to speak clearly, young Margaret had called her friend Barrie her "fwendy-wendy", resulting in the use of the name "Wendy" for a feminine character in the book. Margaret did not survive long enough to read the book; she died in 1894 at the age of five and was buried at the country estate of her father's friend, Henry Cust, Harry Cockayne Cust, in Cockayne Hatley, Bedfordshire. After Robert Louis Stevenson received a letter from Henley labelled "Private and Confidential" and dated 9 March 1888, in which the latter accused Stevenson's new wife Fanny of plagiarising his cousin

Katharine de Mattos

Katharine Elizabeth Alan de Mattos (née Stevenson; 1851–1939) was a Scottish author and journalist. She was the youngest daughter of Margaret Scott Jones, daughter of Humphrey Herbert Jones of Anglesey and the lighthouse engineer, Alan Stevenson ...

' writing in the story "The Nixie", the two men ended their friendship, though a correspondence of sorts did resume later after mutual friends intervened.

Hospital poems

As Andrzej Diniejko notes, Henley and the "Henley Regatta" (the name by which his followers were humorously referred) "promotedrealism

Realism, Realistic, or Realists may refer to:

In the arts

*Realism (arts), the general attempt to depict subjects truthfully in different forms of the arts

Arts movements related to realism include:

*Classical Realism

*Literary realism, a move ...

and opposed Decadence

The word decadence, which at first meant simply "decline" in an abstract sense, is now most often used to refer to a perceived decay in standards, morals, dignity, religious faith, honor, discipline, or skill at governing among the members ...

" through their own works, and, in Henley's case, "through the works... he published in the journals he edited." Henley published many poems in different collections including ''In Hospital'' (written between 1873 and 1875) and ''A Book of Verses'', published in 1891. He is remembered most for his 1875 poem " Invictus", one of his "hospital poems" that were composed during his isolation as a consequence of early, life-threatening battles with tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...

; this set of works, one of several types and themes he engaged during his career, are said to have developed the artistic motif of the "poet as a patient" and to have anticipated modern poetry "not only in form, as experiments in free verse containing abrasive narrative shifts and internal monologue, but also in subject matter."

Forming the subject matter of the "hospital poems" were often Henley's observations of the plights of the patients in the hospital beds around him. Specifically the poem "Suicide" depicts not only the deepest depths of the human emotions, but also the horrid conditions of the working class Victorian poor in Britain. As Henley observed firsthand, the stress of poverty and the vice of addiction pushed a man to the brink of human endurance. In part, the poem reads:

Publishing career

After his recovery, Henley began by earning his living as a journalist and publisher. The sum total of Henley's professional and artistic efforts is said to have made him an influential voice in lateVictorian Britain

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardia ...

, perhaps with a role as central in his time as that of Samuel Johnson in the eighteenth century. As an editor of a series of literary magazines and journals, Henley was empowered to choose each issue's contributors, as well as to offer his own essays, criticism, and poetic works; like Johnson, he said to have "exerted a considerable influence on the literary culture of his time."

For a short period in 1877 and 1878, Henley was hired to edit ''The London Magazine

''The London Magazine'' is the title of six different publications that have appeared in succession since 1732. All six have focused on the arts, literature and miscellaneous topics.

1732–1785

''The London Magazine, or, Gentleman's Monthly I ...

'', "which was a society paper", and "a journal of a type more usual in Paris than London, written for the sake of its contributors rather than of the public." In addition to his inviting its articles and editing all content, Henley anonymously contributed tens of poems to the journal, some of which were described by contemporaries as "brilliant" (later published in a compilation by Gleeson White

Joseph William Gleeson White (1851–1898), often known as Gleeson White, was an English writer on art.

Life

He was born in Christchurch, Dorset and educated at Christ Church School and afterward became a member of the Art Workers Guild. ...

). In his selection White included a considerable number of pieces from London, and only after he had completed the selection did he discover that the verses were all by one hand, that of Henley. In the following year, H. B. Donkin, in his volume ''Voluntaries For an East London Hospital'' (1887), included Henley's unrhymed rhythms recording the poet's memories of the old Edinburgh Infirmary. Later, Alfred Nutt

Alfred Trübner Nutt (22 November 1856 – 21 May 1910) was a British publisher who studied and wrote about folklore and Celtic studies.

Biography

Nutt was born in London, the eldest son of publisher David Nutt. His mother was the granddaughter ...

published these and others in his ''A Book of Verse''.

In 1889, Henley became editor of the '' Scots Observer'', an Edinburgh journal of the arts and current events. After its headquarters were transferred to London in 1891, it became the '' National Observer'' and remained under Henley's editorship until 1893. The paper had almost as many writers as readers, as Henley said, and its fame was confined mainly to the literary class, but it was a lively and influential contributor to the literary life of its era. Serving under Henley as his assistant editor, "right-hand-man", and close friend was Charles Whibley

Charles Whibley (9 December 1859 – 4 March 1930) was an English literary journalist and author. In literature and the arts, his views were progressive. He supported James Abbott McNeill Whistler (they had married sisters). He also recommended ...

. The journal's outlook was conservative and often sympathetic to the growing imperialism of its time. Among other services to literature, it published Rudyard Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)''The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English novelist, short-story writer, poet, and journalist. He was born in British India, which inspired much of his work.

...

's ''Barrack-Room Ballads

The Barrack-Room Ballads are a series of songs and poems by Rudyard Kipling, dealing with the late-Victorian British Army and mostly written in a vernacular dialect. The series contains some of Kipling's best-known works, including the poems " Gu ...

'' (1890–92).

Death

In 1902, Henley fell from a railway carriage. This accident caused his latent tuberculosis to flare up, and he died of it on 11 July 1903, at the age of 53, at his home in Woking, Surrey. After cremation at the local crematorium his ashes were interred in his daughter's grave in the churchyard at Cockayne Hatley in

In 1902, Henley fell from a railway carriage. This accident caused his latent tuberculosis to flare up, and he died of it on 11 July 1903, at the age of 53, at his home in Woking, Surrey. After cremation at the local crematorium his ashes were interred in his daughter's grave in the churchyard at Cockayne Hatley in Bedfordshire

Bedfordshire (; abbreviated Beds) is a ceremonial county in the East of England. The county has been administered by three unitary authorities, Borough of Bedford, Central Bedfordshire and Borough of Luton, since Bedfordshire County Council ...

. At the time of his death Henley's personal wealth was valued at £840. His widow, Anna, moved to 213 West Campbell-St, Glasgow, where she lived until her death.

Memorial

There is a bust of Henley in the crypt of St Paul's Cathedral.Legacy

During his lifetime Henley had become fairly well known as a poet. His poetry had even made its way to the United States, inspiring several different contributors from across the country to pen articles about him. In 1889 the ''Chicago Daily Tribune'' ran an article about the promise that Henley showed in the field of poetry. After Henley's death in 1903 an acquaintance in Boston wrote a piece about her impression of Henley, saying of him, "There was in him something more than the patient resignation of the religious sufferer, who had bowed himself to the uses of adversity. Deep in his nature lay an inner well of cheerfulness, and a spontaneous joy of living, that nothing could drain dry, though it dwindled sadly after the crowning affliction of his little daughter's death." Henley was known as a man of inner resolve and character that transferred into his works, but also made an impression on his peers and friends. The loss of his daughter was a deeply traumatising event in Henley's life but did not truly dampen his outlook on life as a whole. While it has been observed that Henley's poetry "almost fell into undeserved oblivion," the appearance of " Invictus" as a continuing popular reference and the renewed availability of his work, through online databases and archives have meant that Henley's significant influence on culture and literary perspectives in the late- Victorian period is not forgotten.In art and popular culture

George Butterworth

George Sainton Kaye Butterworth, MC (12 July 18855 August 1916) was an English composer who was best known for the orchestral idyll '' The Banks of Green Willow'' and his song settings of A. E. Housman's poems from ''A Shropshire Lad''.

Early ...

set four of Henley's poems to music in his 1912 song cycle

A song cycle (german: Liederkreis or Liederzyklus) is a group, or cycle (music), cycle, of individually complete Art song, songs designed to be performed in a sequence as a unit.Susan Youens, ''Grove online''

The songs are either for solo voice ...

'' Love Blows As the Wind Blows.'' Henley's poem, "Pro Rege Nostro", became popular during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

as a piece of patriotic verse, containing the following refrainThe same poem and its sentiments have since been parodied by those unhappy with the jingoism they feel it expresses or the propagandistic use to which it was put during WWI to inspire patriotism and sacrifice in the British public and young men heading off to war. The poem is referenced in the title, "England, My England

''England, My England'' is a 1995 British historical film directed by Tony Palmer and starring Michael Ball, Simon Callow, Lucy Speed and Robert Stephens. It depicts the life of the composer Henry Purcell, seen through the eyes of a playwrigh ...

", a short story by D. H. Lawrence

David Herbert Lawrence (11 September 1885 – 2 March 1930) was an English writer, novelist, poet and essayist. His works reflect on modernity, industrialization, sexuality, emotional health, vitality, spontaneity and instinct. His best-k ...

, and also in ''England, Their England

''England, Their England'' (1933) is an affectionately satirical comic novel of 1920s English urban and rural society by the Scottish writer A. G. Macdonell. It is particularly famed for its portrayal of village cricket.

Social satire

One of a ...

,'' a satiric novel by A. G. Macdonell about 1920s English society.

Nelson Mandela recited the poem " Invictus" to other prisoners incarcerated alongside him at Robben Island

Robben Island ( af, Robbeneiland) is an island in Table Bay, 6.9 kilometres (4.3 mi) west of the coast of Bloubergstrand, north of Cape Town, South Africa. It takes its name from the Dutch word for seals (''robben''), hence the Dutch/Afrik ...

, some believe because it expressed in its message of self-mastery Mandela's own Victorian ethic. This historical event was captured in fictional form in the Clint Eastwood film '' Invictus'' (2009), wherein the poem is referenced several times. In that fictionalised account, the poem becomes a central inspirational gift from actor Morgan Freeman's Mandela to Matt Damon

Matthew Paige Damon (; born October 8, 1970) is an American actor, film producer, and screenwriter. Ranked among ''Forbes'' most bankable stars, the films in which he has appeared have collectively earned over $3.88 billion at the North Ameri ...

's Springbok

The springbok (''Antidorcas marsupialis'') is a medium-sized antelope found mainly in south and southwest Africa. The sole member of the genus ''Antidorcas'', this bovid was first described by the German zoologist Eberhard August Wilhelm ...

rugby

Rugby may refer to:

Sport

* Rugby football in many forms:

** Rugby league: 13 players per side

*** Masters Rugby League

*** Mod league

*** Rugby league nines

*** Rugby league sevens

*** Touch (sport)

*** Wheelchair rugby league

** Rugby union: 1 ...

team captain Francois Pienaar

Jacobus Francois Pienaar (born 2 January 1967) is a retired South African rugby union player. He played flanker for South Africa (the Springboks) from 1993 until 1996, winning 29 international caps, all of them as captain. He is best known fo ...

, on the eve of the underdog Springboks' victory in the post-apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

1995 Rugby World Cup held in South Africa.

In Chapter Two of her first volume of autobiography, ''I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings

''I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings'' is a 1969 autobiography describing the young and early years of American writer and poet Maya Angelou. The first in a seven-volume series, it is a coming-of-age story that illustrates how strength of charact ...

'' (1969), Maya Angelou writes in passing that she "enjoyed and respected" Henley's works among others such as Poe's and Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)''The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English novelist, short-story writer, poet, and journalist. He was born in British Raj, British India, which inspired much o ...

's, but had no "loyal passion" for them.

Joe Orton, English playwright of the 1960s, based the title and theme of his breakthrough play ''The Ruffian on the Stair

''The Ruffian On the Stair'' is a play by British playwright Joe Orton which was first broadcast on BBC Radio in 1964, in a production by John Tydeman. It is an unsympathetic yet comedic one-act portrayal of working class England, as played out ...

'', which was broadcast on BBC radio in 1964, on the opening lines of Henley's poem ''Madame Life's a Piece in Bloom'':

Henley's 1887 Villon's Straight Tip to All Cross Coves

' (a free translation of François Villon's ''Tout aux tavernes et aux filles'') was recited by

Ricky Jay

Richard Jay Potash (June 26, 1946 – November 24, 2018) was an American stage magician, actor and writer. In a profile for ''The New Yorker'', Mark Singer called Jay "perhaps the most gifted sleight of hand artist alive". In addition to sleight ...

as part of his solo show, ''Ricky Jay and His 52 Assistants'' (1994). The poem was set to music and release with a video in July 2020 by the folk band Stick in the Wheel.

Works

Editions

* ''The London

"The London" is a song by American rapper Young Thug featuring fellow American rappers J. Cole and Travis Scott. It was released through Atlantic Records and 300 Entertainment as the lead single and closing track from Thug's debut studio album, ...

'', 1877–78, "a society paper" Henley edited for this short period, and to which he contributed "a brilliant series of… poems" which were only later attributed publicly to him in a published compilation from Gleeson White (see below).

* In 1890, Henley published ''Views and Reviews'', a volume of notable criticisms, which he described as "less a book than a mosaic of scraps and shreds recovered from the shot rubbish of some fourteen years of journalism". The criticisms, covering a wide range of authors (all English or French save Heinrich Heine and Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

), were remarkable for their insight. Robert Louis Stevenson wrote that he had not received the same thrill of poetry so intimate and so deep since George Meredith

George Meredith (12 February 1828 – 18 May 1909) was an English novelist and poet of the Victorian era. At first his focus was poetry, influenced by John Keats among others, but he gradually established a reputation as a novelist. '' The Ord ...

's "Joy of Earth" and "Love in the Valley": "I did not guess you were so great a magician. These are new tunes; this is an undertone of the true Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label= Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label ...

. These are not verse; they are poetry." In 1895, Henley's poem, " Macaire", was published in a volume with the other plays.

* With John Stephen Farmer

John Stephen Farmer (7 March 1854 – 18 January 1916) also known as J. S. Farmer was a British lexicographer, spiritualist and writer. He was most well known for his seven volume dictionary of slang.

Career

Farmer was born in Bedford. His life ...

, Henley edited a seven volume dictionary of '' Slang and its analogues'' (1890–1904).

* Henley did other notable work for various publishers: the ''Lyra Heroica'', 1891; ''A Book of English Prose'' (with Charles Whibley

Charles Whibley (9 December 1859 – 4 March 1930) was an English literary journalist and author. In literature and the arts, his views were progressive. He supported James Abbott McNeill Whistler (they had married sisters). He also recommended ...

), 1894; the centenary ''Burns'' (with Thomas Finlayson Henderson

__NOTOC__

Thomas Finlayson Henderson (25 May 1844 – 25 December 1923), often credited as T. F. Henderson, was a Scottish historian, author and editor. Henderson was a prolific author and contributed entries on Scottish figures for the '' Dict ...

) in 1896–1897, in which Henley's Essay (published separately in 1898) roused considerable controversy. In 1892 he undertook for Alfred Nutt the general editorship of the ''Tudor Translations''; and in 1897 began for the publisher William Heinemann an edition of Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and has been regarded as among the ...

, which did not proceed beyond one volume of his letters.

Poetry

* The poems of ''In Hospital'' are noteworthy as some of the earliestfree verse

Free verse is an open form of poetry, which in its modern form arose through the French '' vers libre'' form. It does not use consistent meter patterns, rhyme, or any musical pattern. It thus tends to follow the rhythm of natural speech.

Defi ...

written in the U.K. . Arguably Henley's best-remembered work is the poem " Invictus", written in 1875. It is said that this was written as a demonstration of his resilience following the amputation of his foot due to tubercular infection. Henley stated that the main theme of his poem was "The idea that one's decisions and iron will to overcome life's obstacles, defines one's fate".

* In ''Ballades and Rondeaus, Chants Royal, Sestinas, Villanelles, &c…'' (1888), compiled by Gleeson White, including 30 of Henley's works, a "selection of poems in old French forms." The poems were mostly produced by Henley while editing ''The London'' in 1877–78, but also included a few works unpublished or from other sources (''Belgravia,'' ''The Magazine of Art

''The Magazine of Art'' was an illustrated monthly British journal devoted to the visual arts, published from May 1878 to July 1904 in London and New York City by Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co. It included reviews of exhibitions, articles about art ...

''); appearing were a dozen of his ballad

A ballad is a form of verse, often a narrative set to music. Ballads derive from the medieval French ''chanson balladée'' or ''ballade'', which were originally "dance songs". Ballads were particularly characteristic of the popular poetry and ...

s, including "Of Dead Actors" and "Of the Nothingness of Things", his rondels "Four Variations" and "The Ways of Death", ten of his Sicilian octave

The Sicilian octave ( Italian: ''ottava siciliana'') is a verse form consisting of eight lines of eleven syllables each, called a hendecasyllable. The form is common in late medieval Italian poetry. In English poetry, iambic pentameter is often ...

s including "My Love to Me" and "If I were King", a triolet

A triolet (, ) is almost always a stanza poem of eight lines, though stanzas with as few as seven lines and as many as nine or more have appeared in its history. Its rhyme scheme is ABaAabAB (capital letters represent lines repeated verbatim) and ...

by the same name, three villanelle

A villanelle, also known as villanesque,Kastner 1903 p. 279 is a nineteen-line poetic form consisting of five tercets followed by a quatrain. There are two refrains and two repeating rhymes, with the first and third line of the first tercet rep ...

s including "Where's the Use of Sighing", and a pair of burlesques.About the selection of so many of his works, Gleeson White, 1888, op cit., states: "In a society paper, ''The London'', a brilliant series of these poems appeared during 1877-8. After a selection was made for this volume, it was discovered that they were all by one author, Mr. W. E. Henley, who most generously permitted the whole of those chosen to appear, and to be for the first time publicly attributed to him. The poems themselves need no apology, but in the face of so many from his pen, it is only right to explain the reason for the inclusion of so large a number."

* Editing ''Slang and its analogues'' inspired Henley's two translations of ballades by François Villon

François Villon ( Modern French: , ; – after 1463) is the best known French poet of the Late Middle Ages. He was involved in criminal behavior and had multiple encounters with law enforcement authorities. Villon wrote about some of these ...

into thieves' slang.

* In 1892, Henley published a second volume of poetry, named after the first poem, "The Song of the Sword" but later re-titled ''London Voluntaries'' after another section in the second edition (1893).

* ''Hawthorn and Lavender, with Other Verses'' (1901), a collection entirely of Henley's,William Ernest Henley, 1901, ''Hawthorn and Lavender, with Other Verses'', New York: Harper and Bros. (orig, London, England:David Nutt at the Sign of the Phœnix in Long Acre), sean

accessed 9 May 2015. with the title major work, and 16 additional poems, including a dedication to his wife (and epilogue, both penned in

Worthing

Worthing () is a seaside town in West Sussex, England, at the foot of the South Downs, west of Brighton, and east of Chichester. With a population of 111,400 and an area of , the borough is the second largest component of the Brighton and Ho ...

), the collection is composed of 4 sections; the first, the title piece "Hawthorn and Lavender" in 50 parts over 65 pages. The second section is of 13 short poems, called "London Types", including examples from "Bus-Driver" to " Beefeater" to "Barmaid". The third section contains "Three Prologues" associated with theatrical works that Henley supported, including "Beau Austin" (by Henley and Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as ''Treasure Island'', ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll a ...

, that played at Haymarket Theatre in late 1890), "Richard Savage" (by J. M. Barrie

Sir James Matthew Barrie, 1st Baronet, (; 9 May 1860 19 June 1937) was a Scottish novelist and playwright, best remembered as the creator of Peter Pan. He was born and educated in Scotland and then moved to London, where he wrote several succ ...

and H. B. Marriott Watson that played at Criterion Theatre

The Criterion Theatre is a West End theatre at Piccadilly Circus in the City of Westminster, and is a Grade II* listed building. It has a seating capacity of 588.

Building the theatre

In 1870, the caterers Spiers and Pond began developmen ...

in spring 1891, and "Admiral Guinea" (by again by Henley and Stevenson, that played at Avenue Theatre

The Playhouse Theatre is a West End theatre in the City of Westminster, located in Northumberland Avenue, near Trafalgar Square, central London. The Theatre was built by F. H. Fowler and Hill with a seating capacity of 1,200. It was rebuilt i ...

in late 1897). The fourth and final section contains 5 pieces, mostly shorter, and mostly pieces "In Memoriam".

* ''A Song of Speed'', his last published poem two months before his death.

Plays

* During 1892, Henley also published three plays written with Stevenson: ''Beau Austin'', ''Deacon Brodie,'' about a corrupt Scottish deacon turned housebreaker, and ''Admiral Guinea''. ''Deacon Brodie'' was produced in Edinburgh in 1884 and later in London.Herbert Beerbohm Tree

Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree (17 December 1852 – 2 July 1917) was an English actor and theatre manager.

Tree began performing in the 1870s. By 1887, he was managing the Haymarket Theatre in the West End, winning praise for adventurous progr ...

produced ''Beau Austin'' at the Haymarket on 3 November 1890, and ''Macaire'' at His Majesty's on 2 May 1901.

Further reading

* Carol Rumens, 2010, "Poem of the week: ''Waiting'' by W.E. Henley," ''The Guardian'' (online), 11 January 2010, seaccessed 9 May 2015. Quote: "Henley's 'Waiting,' from his 'In Hospital' sequence of poems far outshines his better known 'Invictus.'" * Andrzej Diniejko, 2011, "William Ernest Henley: A Biographical Sketch," at ''Victorian Web'' (online), updated 19 July 2011, se

accessed 9 May 2015. * Jerome Hamilton Buckley, 1945, ''William Ernest Henley: A Study in the Counter-Decadence of the Nineties,'' Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

''Victorian Web'' article on Henley.

* Edward H. Cohen, 1974, ''The Henley-Stevenson Quarrel,'' Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press

* John Connell, 1949, ''W. E. Henley,'' London: Constable.

* Donald Davidson, 1937, ''British Poetry of the Eighteen-Nineties,'' Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran

* Maria H. Frawley, 2004, ''Invalidism and Identity in Nineteenth-century Britain,'' IL: University of Chicago Press

* Kennedy Williamson, 1930, ''W. E. Henley. A Memoir,'' London: Harold Shaylor.

Notes

* James supplies a personal assessment of Henley's manner and influence (p. 271).External links

* *Works by or about William Ernest Henley

at HathiTrust *

Poetry Archive: 137 poems of William Ernest Henley

* " The Difference", a poem by

Florence Earle Coates

Florence Van Leer Earle Nicholson Coates (July 1, 1850 – April 6, 1927) was an American poet, whose prolific output was published in many literary magazines, some of it set to music. She was mentored by the English poet Matthew Arnold, with wh ...

William Ernest Henley: Profile and Poems at Poets.org

* * William Ernest Henley Collection. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. {{DEFAULTSORT:Henley, William Ernest English literary critics English magazine editors People from Gloucester English amputees 1849 births 1903 deaths People educated at The Crypt School, Gloucester 20th-century deaths from tuberculosis English male poets 19th-century English poets 19th-century English male writers English male non-fiction writers Tuberculosis deaths in England Robert Louis Stevenson