W. Averell Harriman on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Averell Harriman (November 15, 1891July 26, 1986), better known as Averell Harriman, was an American Democratic politician, businessman, and diplomat. The son of railroad baron E. H. Harriman, he served as

Harriman served as ambassador to the Soviet Union until January 1946. When he returned to the United States, he worked hard to get

Harriman served as ambassador to the Soviet Union until January 1946. When he returned to the United States, he worked hard to get

"AFL-CIO's Dark Past"

November 22, 2004, on laboreducator.org

Les belles aventures de la CIA en France

, January 8, 2008, ''

Reflecting an earlier simmering feud, Harriman was appalled when Johnson's newly appointed National Security Adviser, W.W. Rostow, told him that he did not expect the bombing of North Vietnam to continue to such point that it finally caused a nuclear showdown between the Soviet Union and the United States, saying that only from extreme situations do lasting settlements emerge. In February 1967, Harriman was involved in peace negotiations in London involving his deputy Chester Cooper, the British Prime Minister Harold Wilson and a visiting Kosygin who hinted that he was carrying a peace offer from Hanoi. Kosygin asked for a 48-hour-long bombing pause as a sign of good faith in the negotiations, which Rostow persuaded Johnson to reject. Harriman had Cooper draft a letter to Johnson protesting the failure of Operation Sunflower. Upon reading Cooper's letter with its threats of resignation, Harriman told him: "I can't send this. It would be all right for you to send. You're expendable". Cooper was so offended that he did not speak to Harriman for the next days, finally leading the famously cantankerous Harriman to sent a letter of apology together with a bottle of Calon Segur wine. In June 1967, Harriman became involved in another attempt at peace code-named Operation Pennsylvania. A professor of political science at Harvard,

Reflecting an earlier simmering feud, Harriman was appalled when Johnson's newly appointed National Security Adviser, W.W. Rostow, told him that he did not expect the bombing of North Vietnam to continue to such point that it finally caused a nuclear showdown between the Soviet Union and the United States, saying that only from extreme situations do lasting settlements emerge. In February 1967, Harriman was involved in peace negotiations in London involving his deputy Chester Cooper, the British Prime Minister Harold Wilson and a visiting Kosygin who hinted that he was carrying a peace offer from Hanoi. Kosygin asked for a 48-hour-long bombing pause as a sign of good faith in the negotiations, which Rostow persuaded Johnson to reject. Harriman had Cooper draft a letter to Johnson protesting the failure of Operation Sunflower. Upon reading Cooper's letter with its threats of resignation, Harriman told him: "I can't send this. It would be all right for you to send. You're expendable". Cooper was so offended that he did not speak to Harriman for the next days, finally leading the famously cantankerous Harriman to sent a letter of apology together with a bottle of Calon Segur wine. In June 1967, Harriman became involved in another attempt at peace code-named Operation Pennsylvania. A professor of political science at Harvard,

Harriman's first marriage, two years after graduating from Yale, was to Kitty Lanier Lawrence. Lawrence was the great-granddaughter of

Harriman's first marriage, two years after graduating from Yale, was to Kitty Lanier Lawrence. Lawrence was the great-granddaughter of

"Leadership in World Affairs."

''

"Averell Harriman, the Russians and the Origins of the Cold War in Europe, 1943–45."

''

online

* Costigliola, Frank. "Archibald Clark Kerr, Averell Harriman, and the fate of the wartime alliance." ''Journal of Transatlantic Studies'' 9.2 (2011): 83–97. * Costigliola, Frank. "Ambassador W. Averell Harriman and the Shift in US Policy toward Moscow after Roosevelt's Death." in ''Challenging US Foreign Policy'' (Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2011) pp. 36–55. * Costigliola, Frank. "Pamela Churchill, wartime London, and the making of the special relationship." ''Diplomatic History ''36.4 (2012): 753–762. * Chandler, Harriette L

"The Transition to Cold Warrior: the Evolution of W. Averell Harriman's Assessment of the U.S.S.R.'s Polish Policy, October 1943 Warsaw Uprising."

''East European Quarterly'' 1976 10(2): 229–245. . * Clemens, Diane S

"Averell Harriman, John Deane, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the 'Reversal of Co-operation' with the Soviet Union in April 1945."

''

''The Wise Men: Six Friends and the World They Made: Acheson, Bohlen, Harriman, Kennan, Lovett, McCloy''

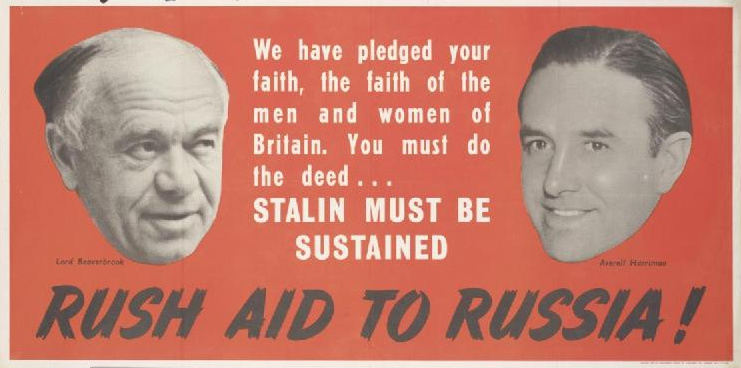

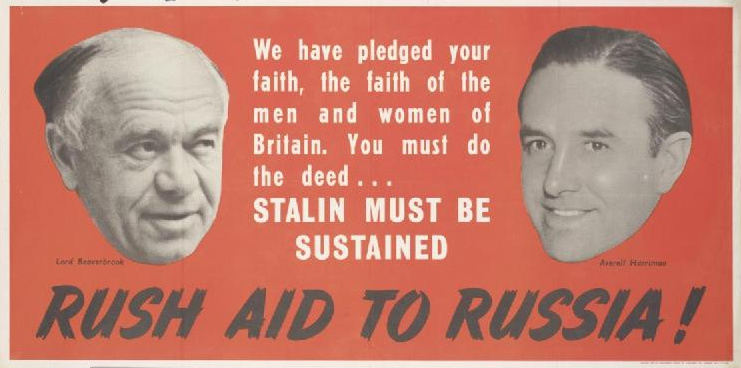

"The Harriman-Beaverbrook Mission and the Debate over Unconditional Aid for the Soviet Union, 1941."

''

"W. Averell Harriman and the Polish Question, December 1943-August 1944."

''

"Patronage in New York State, 1955–1959."

''

"The Abortive American Loan to Russia and the Origins of the Cold War, 1943–1946."

''

"Averell Harriman Has Changed His Mind: The Seattle Speech and the Rhetoric of Cold War Confrontation"

''Cold War History'', 9 (May 2009), 267–86. * Wehrle, Edmund F

"'A Good, Bad Deal': John F. Kennedy, W. Averell Harriman, and the Neutralization of Laos, 1961–1962."

''

''America and Russia in a changing world: A half century of personal observation''

(1971) * W. Averell Harriman

''Public papers of Averell Harriman, fifty-second governor of the state of New York, 1955–1959''

(1960) * Harriman, W. Averell and Abel, Elie. ''Special Envoy to Churchill and Stalin, 1941–1946.'' (1975). 595 pp.

Library of Congress

* W. Averell Harriman has bee

interviewed

as part o

a site at the ttps://web.archive.org/web/20080208215607/http://www.generalsandbrevets.com/ngc/corse.htm Library of Congress * * * * , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Harriman, W. Averell 1891 births 1986 deaths Ambassadors of the United States to the Soviet Union 20th-century American diplomats Ambassadors of the United States to the United Kingdom American Episcopalians American people of English descent American polo players American racehorse owners and breeders 20th-century American railroad executives Brown Brothers Harriman & Co. people Cold War diplomats Democratic Party governors of New York (state) Franklin D. Roosevelt administration personnel Groton School alumni Kennedy administration personnel Lyndon B. Johnson administration personnel Politicians from New York City Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients Truman administration cabinet members Candidates in the 1952 United States presidential election Candidates in the 1956 United States presidential election 20th-century American politicians United States Secretaries of Commerce Yale University alumni Harriman family Under Secretaries of State for Political Affairs Psi Upsilon

Secretary of Commerce

The United States secretary of commerce (SecCom) is the head of the United States Department of Commerce. The secretary serves as the principal advisor to the president of the United States on all matters relating to commerce. The secretary rep ...

under President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Harry S. Truman, and later as the 48th governor of New York. He was a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1952 and 1956, as well as a core member of the group of foreign policy elders known as " The Wise Men".

While attending Groton School

Groton School (founded as Groton School for Boys) is a private college-preparatory boarding school located in Groton, Massachusetts. Ranked as one of the top five boarding high schools in the United States in Niche (2021–2022), it is affiliated ...

and Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the w ...

, he made contacts that led to creation of a banking firm that eventually merged into Brown Brothers Harriman & Co. He owned parts of various other companies, including Union Pacific Railroad

The Union Pacific Railroad , legally Union Pacific Railroad Company and often called simply Union Pacific, is a freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Paci ...

, Merchant Shipping Corporation, and Polaroid Corporation

Polaroid is an American company best known for its instant film and cameras. The company was founded in 1937 by Edwin H. Land, to exploit the use of its Polaroid polarizing polymer. Land ran the company until 1981. Its peak employment was 21,0 ...

. During the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harriman served in the National Recovery Administration

The National Recovery Administration (NRA) was a prime agency established by U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) in 1933. The goal of the administration was to eliminate " cut throat competition" by bringing industry, labor, and governm ...

and on the Business Advisory Council before moving into foreign policy roles. After helping to coordinate the Lend-Lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (), was a policy under which the United States supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and other Allied nations with food, oil, ...

program, Harriman served as the ambassador to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, and attended the major World War II conferences. After the war, he became a prominent advocate of George F. Kennan

George Frost Kennan (February 16, 1904 – March 17, 2005) was an American diplomat and historian. He was best known as an advocate of a policy of containment of Soviet expansion during the Cold War. He lectured widely and wrote scholarly hist ...

's policy of containment

Containment was a geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term '' cordon sanitaire'', which ...

. He also served as Secretary of Commerce, and coordinated the implementation of the Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred over $13 billion (equivalent of about $ in ) in economic re ...

.

In 1954, Harriman defeated Republican Senator Irving Ives

Irving McNeil Ives (January 24, 1896 – February 24, 1962) was an American politician and founding dean of the Cornell University School of Industrial and Labor Relations. A Republican, he served as a United States Senator from New York from ...

to become the Governor of New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

. He served a single term before his defeat by Nelson Rockefeller

Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller (July 8, 1908 – January 26, 1979), sometimes referred to by his nickname Rocky, was an American businessman and politician who served as the 41st vice president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. A member of t ...

in the 1958 election. Harriman unsuccessfully sought the presidential nomination at the 1952 Democratic National Convention

The 1952 Democratic National Convention was held at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois from July 21 to July 26, 1952, which was the same arena the Republicans had gathered in a few weeks earlier for their national convention f ...

and the 1956 Democratic National Convention

The 1956 Democratic National Convention nominated former Governor Adlai Stevenson of Illinois for president and Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee for vice president. It was held in the International Amphitheatre on the South Side of Chic ...

. Although Harriman had Truman's backing at the 1956 convention, the Democrats nominated Adlai Stevenson II

Adlai Ewing Stevenson II (; February 5, 1900 – July 14, 1965) was an American politician and diplomat who was twice the Democratic nominee for President of the United States. He was the grandson of Adlai Stevenson I, the 23rd vice president o ...

in both elections.

After his gubernatorial defeat, Harriman became a widely respected foreign policy elder within the Democratic Party. He helped negotiate the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty

The Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT) is the abbreviated name of the 1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, which prohibited all test detonations of nuclear weapons except for those conducted ...

during President John F. Kennedy's administration, and was deeply involved in the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

during the Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

administration. After Johnson left office in 1969, Harriman became affiliated with various organizations, including the Club of Rome

The Club of Rome is a nonprofit, informal organization of intellectuals and business leaders whose goal is a critical discussion of pressing global issues. The Club of Rome was founded in 1968 at Accademia dei Lincei in Rome, Italy. It consists ...

and the Council on Foreign Relations

The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) is an American think tank specializing in U.S. foreign policy and international relations. Founded in 1921, it is a nonprofit organization that is independent and nonpartisan. CFR is based in New York Ci ...

.

Early life and education

Better known as Averell Harriman, he was born inNew York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, the son of railroad baron Edward Henry Harriman

Edward Henry Harriman (February 20, 1848 – September 9, 1909) was an American financier and railroad executive.

Early life

Harriman was born on February 20, 1848, in Hempstead, New York, the son of Orlando Harriman Sr., an Episcopal clergyman ...

and Mary Williamson Averell. He was the brother of E. Roland Harriman and Mary Harriman Rumsey

Mary Harriman Rumsey (November 17, 1881 – December 18, 1934) was the founder of The Junior League for the Promotion of Settlement Movements, later known as the Junior League of the City of New York of the Association of Junior Leagues Internati ...

. Harriman was a close friend of Hall Roosevelt, the brother of Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt () (October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt's four ...

.

During the summer of 1899, Harriman's father organized the Harriman Alaska Expedition, a philanthropic-scientific survey of coastal Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U ...

and Russia that attracted 25 of the leading scientific, naturalist, and artist luminaries of the day, including John Muir

John Muir ( ; April 21, 1838December 24, 1914), also known as "John of the Mountains" and "Father of the National Parks", was an influential Scottish-American naturalist, author, environmental philosopher, botanist, zoologist, glaciologis ...

, John Burroughs

John Burroughs (April 3, 1837 – March 29, 1921) was an American naturalist and nature essayist, active in the conservation movement in the United States. The first of his essay collections was ''Wake-Robin'' in 1871.

In the words of his bi ...

, George Bird Grinnell

George Bird Grinnell (September 20, 1849 – April 11, 1938) was an American anthropologist, historian, naturalist, and writer. Grinnell was born in Brooklyn, New York, and graduated from Yale University with a B.A. in 1870 and a Ph.D. in 1880. ...

, C. Hart Merriam, Grove Karl Gilbert

Grove Karl Gilbert (May 6, 1843 – May 1, 1918), known by the abbreviated name G. K. Gilbert in academic literature, was an American geologist.

Biography

Gilbert was born in Rochester, New York and graduated from the University of Rochester. D ...

, and Edward Curtis

Edward Sherriff Curtis (February 19, 1868 – October 19, 1952) was an American photographer and ethnologist whose work focused on the American West and on Native American people. Sometimes referred to as the "Shadow Catcher", Curtis traveled ...

, along with 100 family members and staff, aboard the steamship ''George Elder''. Young Harriman would have his first introduction to Russia, a nation on which he would spend much attention in his later life in public service.

He attended Groton School

Groton School (founded as Groton School for Boys) is a private college-preparatory boarding school located in Groton, Massachusetts. Ranked as one of the top five boarding high schools in the United States in Niche (2021–2022), it is affiliated ...

in Massachusetts before going on to Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wor ...

, where he joined the Skull and Bones

Skull and Bones, also known as The Order, Order 322 or The Brotherhood of Death, is an undergraduate senior secret student society at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. The oldest senior class society at the university, Skull and Bone ...

society and Psi Upsilon

Psi Upsilon (), commonly known as Psi U, is a North American fraternity,''Psi Upsilon Tablet'' founded at Union College on November 24, 1833. The fraternity reports 50 chapters at colleges and universities throughout North America, some of which ...

. He graduated in 1913. After graduating, he inherited one of the largest fortunes in America, and became Yale's youngest Crew coach.

Career

Business affairs

Using money from his father, he established the W.A. Harriman & Co banking business in 1922. His brother Roland joined the business in 1927 and the name was changed toHarriman Brothers & Company

Harriman or Hariman (variant Herriman) is a surname derived from the given name Herman, and in turn occurs as a placename derived from the surname in the United States.

Buildings

* Dr. O.B. Harriman House, a historic home in Hampton, Iowa, U.S. ...

. In 1931 it merged with Brown Bros. & Co. to create the highly successful Wall Street firm Brown Brothers Harriman & Co. Notable employees included George Herbert Walker

George Herbert "Bert" Walker Sr. (June 11, 1875 – June 24, 1953) was an American banker and businessman. He was the maternal grandfather of President George H. W. Bush and a great-grandfather of President George W. Bush, both of whom were na ...

and his son-in-law Prescott Bush

Prescott Sheldon Bush (May 15, 1895 – October 8, 1972) was an American banker as a Wall Street executive investment banker, he represented Connecticut in the from 1952 of the Bush family, he was the father of former Vice President and Pr ...

.

Harriman's main properties included Brown Brothers & Harriman & Co, the Union Pacific Railroad

The Union Pacific Railroad , legally Union Pacific Railroad Company and often called simply Union Pacific, is a freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Paci ...

, the Merchant Shipbuilding Corporation

The Merchant Shipbuilding Corporation (abbreviated MSC) was an American corporation established in 1917 by railroad heir W. Averell Harriman to build merchant ships for the Allied war effort in World War I. The MSC operated two shipyards: the ...

, and venture capital investments that included the Polaroid Corporation

Polaroid is an American company best known for its instant film and cameras. The company was founded in 1937 by Edwin H. Land, to exploit the use of its Polaroid polarizing polymer. Land ran the company until 1981. Its peak employment was 21,0 ...

. Harriman's associated properties included the Southern Pacific Railroad

The Southern Pacific (or Espee from the railroad initials- SP) was an American Class I railroad network that existed from 1865 to 1996 and operated largely in the Western United States. The system was operated by various companies under the ...

(including the Central Pacific Railroad

The Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR) was a rail company chartered by U.S. Congress in 1862 to build a railroad eastwards from Sacramento, California, to complete the western part of the " First transcontinental railroad" in North America. Incor ...

), the Illinois Central Railroad

The Illinois Central Railroad , sometimes called the Main Line of Mid-America, was a railroad in the Central United States, with its primary routes connecting Chicago, Illinois, with New Orleans, Louisiana, and Mobile, Alabama. A line al ...

, Wells Fargo & Co., the Pacific Mail Steamship Co., American Ship & Commerce, Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Aktiengesellschaft (HAPAG

The Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Aktien-Gesellschaft (HAPAG), known in English as the Hamburg America Line, was a transatlantic shipping enterprise established in Hamburg, in 1847. Among those involved in its development were prominent citi ...

), the American Hawaiian Steamship Co., United American Lines, the Guaranty Trust Company, and the Union Banking Corporation.

He served as Chairman of The Business Council

The Business Council is an organization of business leaders headquartered in Washington, D.C.United States Department of Commerce

The United States Department of Commerce is an executive department of the U.S. federal government concerned with creating the conditions for economic growth and opportunity. Among its tasks are gathering economic and demographic data for bus ...

, in 1937 and 1939.The Business Council, Official website, BackgroundPolitics

Harriman's older sister, Mary Rumsey, encouraged Averell to leave his finance job and work with her and their friends, theRoosevelts

The Roosevelt family is an American political family from New York whose members have included two United States presidents, a First Lady, and various merchants, bankers, politicians, inventors, clergymen, artists, and socialites. The progeny ...

, to advance the goals of the New Deal. Averell joined the NRA National Recovery Administration

The National Recovery Administration (NRA) was a prime agency established by U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) in 1933. The goal of the administration was to eliminate " cut throat competition" by bringing industry, labor, and governm ...

, an effort to cartelise the American economy via a Corporate State model (ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1935), marking the beginning of his political career.

Thoroughbred racing

Following the death ofAugust Belmont Jr.

August Belmont Jr. (February 18, 1853 – December 10, 1924) was an American financier. He financed the construction of the original New York City subway (1900–1904) and for many years headed the Interborough Rapid Transit Company, which ran ...

, in 1924, Harriman, George Walker, and Joseph E. Widener purchased much of Belmont's thoroughbred breeding stock. Harriman raced under the nom de course of Arden Farm. Among his horses, Chance Play won the 1927 Jockey Club Gold Cup

The Jockey Club Gold Cup, established in 1919, is a thoroughbred flat race open to horses of either gender three-years-old and up. It has traditionally been the main event of the fall meeting at Belmont Park, just as the Belmont Stakes is of the s ...

. He also raced in partnership with Walker under the name Log Cabin Stable before buying him out. U.S. Racing Hall of Fame inductee Louis Feustel, trainer of Man o' War

Man o' War (March 29, 1917 – November 1, 1947) was an American Thoroughbred racehorse who is widely regarded as the greatest racehorse of all time. Several sports publications, including ''The Blood-Horse'', ''Sports Illustrated'', ESPN, and t ...

, trained the Log Cabin horses until 1926. Of the partnership's successful runners purchased from the August Belmont estate, Ladkin

{{Infobox racehorse

, horsename = Ladkin

, image =

, caption =

, sire = Fair Play

, grandsire = Hastings

, dam = Lading

, damsire = Negofol

, sex = Stallion

, foaled = 1921

, country = United States

, color = Chestnut

, breeder = ...

is best remembered for defeating the European star Epinard in the International Special The International Specials of 1924 were a series of three Thoroughbred horse races held in September and October at three different race tracks in the United States. They were called "International" because the race included the champion from Franc ...

.

War seizures controversy

Harriman's banking business was the mainWall Street

Wall Street is an eight-block-long street in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. It runs between Broadway in the west to South Street and the East River in the east. The term "Wall Street" has become a metonym for ...

connection for German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

companies and the varied U.S. financial interests of Fritz Thyssen, who was a financial backer of the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

until 1938. The Trading With the Enemy Act

Trading with the Enemy Act is a stock short title used for legislation in the United Kingdom and the United States relating to trading with the enemy.

''Trading with the Enemy Acts'' is also a generic name for a class of legislation generally ...

(enacted on October 6, 1917) classified any business transactions for profit with enemy nations as illegal, and any funds or assets involved were subject to seizure by the U.S. government. The declaration of war on the U.S. by Hitler led to a U.S. government order on October 20, 1942, to seize German interests in the U.S., which included Harriman's operations in New York City.

The Harriman business interests seized under the act in October and November 1942 included:

* Union Banking Corporation (UBC) (from Thyssen and Brown Brothers Harriman

Brown Brothers Harriman & Co. (BBH) is the oldest and one of the largest private investment banks in the United States.

* a "Brown Brothers, who are the oldest as well as one of the largest private banking concerns in the country" — ¶ 2

* b " ...

)

* Holland-American Trading Corporation (from Harriman)

* Seamless Steel Equipment Corporation (from Harriman)

* Silesian-American Corporation Silesian-American Corporation (SACO) was registered as a corporation in Delaware in 1926 to assume ownership of the Giesche Spolka Akcyjna (Giesche) that was registered as a corporation in Katowice, Poland earlier during the interwar period. SACO ga ...

(this company was partially owned by a German entity; during the war, the Germans tried to take full control of Silesian-American. In response to that, the American government seized German-owned minority shares in the company, leaving the U.S. partners to carry on the portion of the business in the United States.)

The assets were held by the government for the duration of the war, then returned afterward; UBC was dissolved in 1951.

Compensation for wartime losses in Poland was based on prewar assets. Harriman, who owned vast coal reserves in Poland, was handsomely compensated for them through an agreement between the American and Polish governments. Poles who had owned little but their homes received negligible sums.

World War II diplomacy

Beaverbrook-Harriman mission

Beginning in the spring of 1941, Harriman served President Franklin D. Roosevelt as a special envoy to Europe and helped coordinate theLend-Lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (), was a policy under which the United States supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and other Allied nations with food, oil, ...

program. In August 1941, Harriman was present at the meeting between FDR and Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

at Placentia Bay

Placentia Bay (french: Baie de Plaisance) is a body of water on the southeast coast of Newfoundland, Canada. It is formed by Burin Peninsula on the west and Avalon Peninsula on the east. Fishing grounds in the bay were used by native people long ...

, which yielded the Atlantic Charter

The Atlantic Charter was a statement issued on 14 August 1941 that set out American and British goals for the world after the end of World War II. The joint statement, later dubbed the Atlantic Charter, outlined the aims of the United States and ...

. The joint agreement would establish American and British goals for the period following the end of World War II—before the U.S. was involved in that war—in the form of a common declaration of principles that were eventually endorsed by all of the Allies. Harriman was subsequently dispatched to Moscow to negotiate the terms of the Lend-Lease agreement with the Soviet Union in September 1941, together with the Canadian publishing millionaire Lord Beaverbrook

William Maxwell Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook (25 May 1879 – 9 June 1964), generally known as Lord Beaverbrook, was a Canadian-British newspaper publisher and backstage politician who was an influential figure in British media and politics o ...

, who represented the United Kingdom.Weinberg, Gerhard ''A World At Arms'' p. 288. Harriman tended to follow Beaverbrook's argument that since Germany had committed three million men to the invasion of the Soviet Union—so that the Soviets were doing the bulk of the fighting against the Third Reich—it was in the best interests of the Western powers to do everything to assist the Soviet Union. The decision to aid the Soviet Union was taken against the advice of the U.S. ambassador in Moscow, Laurence Steinhardt

Laurence Adolph Steinhardt (October 6, 1892 – March 28, 1950) was an American economist, lawyer, and senior diplomat of the United States Department of State who served as U.S. Ambassador to six countries. He served as U.S. First Minister to Sw ...

, who from the moment that Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

started on June 22, 1941, had been sending cables predicting the Soviet Union would be rapidly defeated, and that any American aid would thus be wasted. Likewise, General George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Chief of Staff of the US Army under Pre ...

was advising President Roosevelt that it was inevitable that Germany would crush the Soviet Union, and predicted that the Wehrmacht would reach Lake Baikal

Lake Baikal (, russian: Oзеро Байкал, Ozero Baykal ); mn, Байгал нуур, Baigal nuur) is a rift lake in Russia. It is situated in southern Siberia, between the federal subjects of Irkutsk Oblast to the northwest and the ...

by the end of 1941.

The most important result of the Beaverbrook-Harriman mission to Moscow was the conclusion agreed upon between Churchill and Roosevelt that the Soviet Union would not collapse by the end of 1941. Additional conditions of the agreement were that even if the Soviet Union was defeated in 1942, keeping Soviet Russia fighting would impose major losses on the Wehrmacht, which would only benefit the United States and the United Kingdom.Mayers, David "The Great Patriotic War, FDR's Embassy Moscow, and Soviet—US Relations" pp. 299–333 from ''The International History Review'', Volume 33, No. 2, June 2011, p.309 Harriman has been subsequently criticized for not imposing preconditions on American aid to the Soviet Union, but the American historian, Gerhard Weinberg

Gerhard Ludwig Weinberg (born 1 January 1928) is a German-born American diplomatic and military historian noted for his studies in the history of Nazi Germany and World War II. Weinberg is the William Rand Kenan, Jr. Professor Emeritus of History ...

, has defended him on this point, arguing that in 1941, it was Germany—not the Soviet Union—that represented the main danger to the United States. Furthermore, Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

told Harriman that he would refuse American aid if preconditions were attached, leaving Harriman with no alternatives on the issue. Harriman believed if Germany defeated the Soviet Union, then all of the vast natural resources of the Soviet Union would be at the disposal of the ''Reich'', making Germany far more powerful than it already was. Therefore, it was in the best interests of the United States to deny those resources to the ''Reich''. He also pointed out that the defeat of the Soviet Union would free up three million men of the Wehrmacht for operations elsewhere, allowing Hitler to shift money and resources from his army to his navy and potentially increasing the threat to the United States. Harriman told Roosevelt that if Operation Barbarossa was successful in 1941, Hitler would almost certainly defeat Britain in 1942. His promise of $1 billion in aid technically exceeded his brief. Determined to win over the doubtful American public, he used his own funds to purchase time on CBS radio to explain the program in terms of enlightened self-interest

Enlightened self-interest is a philosophy in ethics which states that persons who act to further the interests of others (or the interests of the group or groups to which they belong), ultimately serve their own self-interest.

It has often been ...

. Nonetheless, considerable U.S. public skepticism towards Soviet aid persisted, lifting only with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.Cathal J. Nolan, ''Notable U.S. ambassadors since 1775: a biographical dictionary,'' 137-143.

In a speech in 1972, Harriman stated: "Today people tend to forget that, in 1941, President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill had one prime objective: to destroy Hitler's forces, and win the war in a way that would be least costly in terms of human lives. For over a year, the British alone had borne the brunt of Nazi attacks; for their own self-preservation, they wanted to keep Russia as a fighting ally. Roosevelt had yet another consideration in mind. In those early days of the war, he was fearful that we would eventually be drawn into the conflict, yet he still hoped that our participation could be limited to air and naval forces, with a minimum of ground troops. We are all, to a considerable extent, the product of our experience: Roosevelt had a particular horror of the trench warfare of World War I and he wanted above all to prevent that fate from again befalling American fighting men. He hoped that, with our support, the Red Army would be able to keep the Axis forces engaged. The strength of the British divisions coupled with our own air and sea power might then make it unnecessary for the United States to commit major ground forces on the European continent". The Beaverbrook-Harriman mission promised that the United States and Great Britain would supply the Soviet Union every month with 500 tanks and 400 airplanes, plus tin, copper, and zinc.Rees, Laurence ''World War II Behind Closed Doors'' p. 135. However, the promised supplies had to be sent via the perilous "Murmansk run

The Arctic convoys of World War II were oceangoing convoys which sailed from the United Kingdom, Iceland, and North America to northern ports in the Soviet Union – primarily Arkhangelsk (Archangel) and Murmansk in Russia. There were 78 convoys ...

" through the Arctic Ocean, and only a tiny fraction of what was promised had in fact arrived by December 1941.

On November 25, 1941 (twelve days before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

), Harriman noted that "The United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

is shooting the Germans—German submarines and aircraft at sea." In 1941, a team of officers, led by General Albert Wedemeyer

General Albert Coady Wedemeyer (July 9, 1896 – December 17, 1989) was a United States Army commander who served in Asia during World War II from October 1943 to the end of the war. Previously, he was an important member of the War Planning Board ...

on behalf of General Marshall, drew up the Victory Program, whose premise was that the Soviet Union would be defeated that year, and that to defeat Germany would require the United States to raise by the summer of 1943 a force of 215 divisions comprising 8.7 million men. The Harriman-Beaverbrook mission, whose more optimistic appraisal of Soviet fighting power ran contrary to the more pessimistic assessment, challenged one of the basic assumptions of the Victory Program. The Victory Program, with its call for a 215-division army plus men for the Army Air Corps, the Navy and the Marines that would require massive amounts of equipment, leading to what was known as the Feasibility Dispute within different departments of the government.Kennedy, David ''Freedom From Fear'' pp. 627–628. To build the necessary weapons for such a massive force would require the government essentially to end all civilian production in the U.S, a measure estimated to cause a 60% reduction in living standards. Many in the government felt this would impose a level of sacrifice that the American people would be unwilling to accept. The Feasibility Dispute ended in 1942 with the "civilian" fraction triumphing over the military as Roosevelt decided upon what was known as the "90 division gamble". Roosevelt decided that all of the evidence he received since the Harriman-Beaverbrook mission indicated that the Soviet Union would not be defeated as the Victory Program had assumed, and accordingly the 215 division force envisioned was not necessary and instead he would "gamble" with a 90 division force.

Moscow Conference

In August 1942, Harriman accompanied Churchill to the Moscow Conference to explain to Stalin why the western allies were carrying out operations in North Africa instead of opening the promised second front in France. The meeting was a difficult one with Stalin openly accusing Churchill to his face of lying to him and suggested that the British would not open a second front in Europe because of cowardice, sarcastically saying that the recent defeats suffered by the British 8th Army in North Africa showed how brave the British were against the Wehrmacht.Rees, Laurence ''World War II Behind Closed Doors'' p. 157. Harriman had spent much time after the meeting at the Kremlin reminding Churchill that the Allies needed the Soviet Union and to try not to take Stalin's remarks too personally, saying the fate of the world was hanging in balance. On June 24, 1943, Harriman met with Churchill to tell him that Roosevelt did not want him to attend the up-coming summit meeting with Stalin, saying that it was important to allow Roosevelt who had never met Stalin to establish an "intimate understanding", which would be "impossible" if Churchill was there.Rees, Laurence ''World War II Behind Closed Doors'' p. 198. Churchill rejected this suggestion, sending a telegram to Roosevelt full of hurt feelings saying: "I do not underrate the use that enemy propaganda would make of a meeting between the heads of Soviet Russia and the United States at this juncture with the British Commonwealth and Empire excluded. It would be serious and vexatious, and many would be bewildered and alarmed thereby". Roosevelt in his reply lied by saying that this was just a "misunderstanding" and he had never wanted to exclude Churchill from the summit with Stalin.Four Power declaration

Harriman was appointed asUnited States Ambassador

Ambassadors of the United States are persons nominated by the president to serve as the country's diplomatic representatives to foreign nations, international organizations, and as ambassadors-at-large. Under Article II, Section 2 of the U.S ...

to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

in October 1943. In his 1975 memoir ''Special Envoy to Churchill and Stalin, 1941-1946'', Harriman wrote that Stalin was "the most inscrutable and contradictory character I have ever known", a mysterious man of "high intelligence and fantastic grasp of detail" who possessed much "shrewdness" and "surprising human sensitivity".Kennedy, David ''Freedom From Fear'' p.675. Harriman concluded that Stalin was "better informed than Roosevelt, more realistic than Churchill, in some ways the most effective of the war leaders. At the same time he was, of course, a murderous tyrant". Harriman, who thoroughly enjoyed living in London, did not want to be U.S ambassador in Moscow and only reluctantly accepted the assignment in October 1943 after Roosevelt told him that he was the only man he wanted in Moscow. Harriman was also reluctant to part with his mistress, Pamela Churchill, the wife of Randolph Churchill

Randolph Frederick Edward Spencer-Churchill (28 May 1911 – 6 June 1968) was an English journalist, writer, soldier, and politician. He served as Conservative Member of Parliament (MP) for Preston from 1940 to 1945.

The only son of British ...

.Mayers, David "The Great Patriotic War, FDR's Embassy Moscow, and Soviet—US Relations" pp. 299–333 from ''The International History Review'', Volume 33, No. 2, June 2011, p.316 Although Harriman was one of the richest men in the United States, running a vast business empire comprising investments in railroads, aviation, banks, utilities, shipbuilding, oil production, steel manufacturing, and resorts, this in fact endeared him to the Soviets who believed he represented American capitalist ruling class. Nikita Khrushchev later told Harriman: "We like to do business with you, for you are the master and not the lackey". Stalin viewed the United States through a Marxist prism, which saw American Big Business as the puppeteers and American politicians as the puppets.

At a three power conference in Moscow that took place between October 19 and 30, 1943, Harriman played a major role in representing the United States as part of the American delegation headed by Secretary of State Cordell Hull

Cordell Hull (October 2, 1871July 23, 1955) was an American politician from Tennessee and the longest-serving U.S. Secretary of State, holding the position for 11 years (1933–1944) in the administration of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt ...

while the Soviet delegation was headed by the Foreign Commissar Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...

and the British delegation headed by the Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British Conservative Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achieving rapid promo ...

.Weinberg, Gerhard ''A World At Arms'' p. 620. The main American demands at the Moscow Conference were to have a new international organization replace the League of Nations to be called the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

; to have Soviet Union to agree to adhere to the "unconditional surrender" formula adopted at the Casablanca conference (a major point given that the Soviets sometimes hinted that they were willing to sign a separate peace with Germany); and for the "Big Three" powers whom it was assumed would dominate the post-war world to be a "Big Four" as the Americans wanted China to stand alongside the United States, the Soviet Union, and Great Britain as one of the world's dominant powers. The demand for a "Big Four" instead of a "Big Three" turned out to the main difficulty at the Moscow conference as the British and Soviets did not consider China a major power in any sense. As long as the Soviet Union was engaged in the war against Germany, they not did wish to antagonize Japan with whom they had signed a neutrality agreement in 1941, and the Soviets objected that having Foo Ping Shen, the Chinese ambassador to Moscow, sign the proposed Four Power Declaration would cause tensions with Tokyo. Eventually, after much patient diplomacy, Harriman won out, and a Four Power declaration was signed on October 30, 1943, by Hull, Eden, Molotov and Foo stating that the four permanent members of the United Nations Security Council would be the United States, Great Britain, the Soviet Union and China.

Planning for Operation Overlord and the war's end

Besides for the Four Power declaration, the other issues at the Moscow conference were whether the United States would recognize theFrench Committee of National Liberation

The French Committee of National Liberation (french: Comité français de Libération nationale) was a provisional government of Free France formed by the French generals Henri Giraud and Charles de Gaulle to provide united leadership, orga ...

headed by General Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Governm ...

as the French government-in-exile. Roosevelt had a strong personal aversion to de Gaulle, and throughout the war, the Americans had an "anybody but de Gaulle" attitude. At Moscow, the Americans very reluctantly agreed to Eden's insistence that they extend some recognition to de Gaulle, although the Americans still refused to grant him full recognition, a matter which contributed much to de Gaulle's subsequent anti-Americanism. The question of who the legitimate government of France was posed a major potential problem since the next year Operation Overlord, the invasion of France, was scheduled to take place. Presuming Overlord was successful, the question would arise over whom the Anglo-Americans would turn France over to. Nothing infuriated de Gaulle more than the implication that the Americans would not hand over France to his National Committee after the liberation. Tensions between Great Britain and the Soviet Union over the Arctic supply convoys were eased while the difficulties over supplies coming over Iran were left unresolved despite Harriman's best efforts at playing mediator. On the matter of Germany, the Soviet Union agreed to the "unconditional surrender" formula while it agreed that after the war, Germany was to be disarmed and denazified.

All of the delegations at the Moscow conference agreed that Germany was to be permanently disarmed after the war, which led to the question of whether Germany should be also deindustrialized as well in order to ensure that Germany would never be able to build military weapons again; no consensus was reached over this issue.Weinberg, Gerhard ''A World At Arms'' p. 620-621. The question of what Germany's borders were to be after the war was left unresolved, through everybody at the conference agreed that Germany was going to lose territory with the only question being just how much. One matter where agreement was reached was with Austria as it was announced at the Moscow conference that the ''Anschluss'' of 1938 was to be undone and Austria would have its independence restored after the war.Weinberg, Gerhard ''A World At Arms'' p. 621. Finally, in regards to the ''Reich'', it was agreed that war crimes trials were to take place after the war with lesser war criminals to be tried in the nations where they had committed their crimes while the leaders of Germany were to be tried by a special court consisting of judges from the United Kingdom, the United States and the Soviet Union. The communique in Moscow which announced that war crimes trials would be held after the war was intended primarily as a deterrent to German officials currently engaged in war crimes as it was hoped that the prospect of facing a hangman's noose after the war might change their behavior. As for Italy, it was agreed that the Soviet Union was to send a representative to the Allied Control Commission which governed the liberated parts of Italy and that Italy was to pay reparations to the Soviet Union in the form of ships, as much of the Italian merchant marine was to be handed over to the Soviet Union. No agreement was reached over the question of the Soviet Union's borders after the war, with the Soviets insisting that their postwar borders should be exactly where they were on June 21, 1941, a point that the American delegation and to a lesser extent British delegation resisted.

Relations with Poland and China

At theTehran Conference

The Tehran Conference ( codenamed Eureka) was a strategy meeting of Joseph Stalin, Franklin Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill from 28 November to 1 December 1943, after the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran. It was held in the Soviet Union's embass ...

in late 1943 Harriman was tasked with placating a suspicious Churchill while Roosevelt attempted to gain the confidence of Stalin. The conference highlighted the divisions between the United States and Britain about the postwar world. Churchill was intent on maintaining Britain's empire and carving the postwar world into spheres of influence while the United States upheld the principles of self-determination as laid out in the Atlantic Charter. Harriman mistrusted the Soviet leader's motives and intentions and opposed the spheres approach as it would give Stalin a free hand in eastern Europe. At the Tehran conference, Molotov finally promised Harriman what he long sought, namely that after Germany was defeated, the Soviet Union would declare war on Japan. At Tehran, Roosevelt told Stalin that as a "practical man" who was planning to run for a fourth term in 1944 that he had to think of Polish-American voters, but that he agreed that the Soviets could keep the part of Poland they had annexed in 1939, provided that this was kept a secret until the 1944 election.Rees, Laurence ''World War II Behind Closed Doors'' p. 236. Harriman felt that this was a mistake, as he regarded Roosevelt's statement that the Polish government had to accept the loss of some of its territory as virtually agreeing to allow the Soviets to impose any government they wanted on Poland because it was unlikely that the Polish government-in-exile would agree with the annexation. At the same time, Harriman was jolted when Molotov admitted to him that there had been attempts at arranging a separate German-Soviet peace which would leave the Western Allies to face the full force of the Wehrmacht earlier in 1943, but that the Soviets had rejected the peace overtures.Rees, Laurence ''World War II Behind Closed Doors'' p. 200. The way in which Molotov phrased his account implied to Harriman that in the future the Soviets might be more receptive to such peace offers, which Harriman regarded as an attempt at blackmail. On January 22, 1944, Harriman's daughter Kathleen, whom the British Foreign Office described as "the poor man's Mrs. Roosevelt", traveled to Katyn Forest to see the "evidence" that the Soviet authorities had produced meant to prove that the Katyn Forest massacre had been committed by the Germans in 1941, instead of the Soviets in 1940. Since all of the available evidence suggested that the Soviets had in fact committed the Katyn Forest massacre in April 1940, Harriman later stated that he tried to avoid the subject, telling a Senate hearing "No, I do not recall the subject came up".

Starting in February 1944, Harriman pressed Stalin to open U.S-Soviet staff talks to prepare for when the Soviet Union would enter the war against Japan, only to be told this was "premature" as Stalin stated it would require at least four infantry divisions to invade Manchuria, which would not be possible given that the Soviets were fully involved in the war against Germany.Buhite, Russell ''Decisions at Yalta'' p. 87. For the rest of 1944, Harriman pressed Molotov to bring the head of the Soviet Far Eastern Air Force to Moscow to open staff talks with the U.S military mission about establishing American air bases in either the Vladivostok area or in Kamchatka to allow American aircraft to bomb Japan. Molotov refused to make any firm commitments about allowing American bombers to strike Japan from air bases in the Soviet Union. Another major concern of the Roosevelt administration was to ensure that the Chinese civil war did not resume with the end of World War II, and to do so, the Americans sought a coalition government between the Chinese Communist Party and the Kuomintang. In connection with this, Harriman met Stalin on June 10, 1944, to get from him a rather generalized statement declaring his support for Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

as China's only leader and a promise that he would use his influence with Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also Romanization of Chinese, romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the List of national founde ...

to pressure him to recognize Chiang. In August 1944, Harriman sought permission for American aircraft flying supplies to the ''Armia Krajowa'' rebels fighting in the Warsaw Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising ( pl, powstanie warszawskie; german: Warschauer Aufstand) was a major World War II operation by the Polish underground resistance to liberate Warsaw from German occupation. It occurred in the summer of 1944, and it was led ...

to land at the Poltava airbase as otherwise the American aircraft would have no fuel to make it home.Buhite, Russell ''Decisions at Yalta'' p. 46. On August 16, 1944, the Assistant Commissar for Foreign Affairs, Andrei Vyshinsky, told Harriman that "the Soviet government cannot of course object to English or American aircraft dropping arms in the region of Warsaw since this is an American or British affair. But they decidedly object to American or British aircraft, after dropping arms in the region of Warsaw, landing on Soviet territory, since the Soviet government does not wish to associate themselves either directly or indirectly with the adventure in Warsaw". In a cable to Washington, Harriman wrote: "The Soviet Government's refusal is not based on operational difficulties nor on a denial of the conflict, but on ruthless political calculations".

Negotiations preceding the bombing of Japan

In the summer of 1944, Stalin promised Harriman that the Americans would be allowed to use air bases in the Soviet Far East to bomb Japan, but only if the Americans supplied the Soviet Air Force with hundreds of four engine bombers.Buhite, Russell ''Decisions at Yalta'' p. 88. In September 1944, Stalin expressed much pique to Harriman that the recent Anglo-American communique issued at the Quebec Conference did not mention the Soviet Union, leading him to sarcastically state "if the United States and Great Britain desired to bring the Japanese to their knees without Russian participation, the Russians were ready to do this". When Harriman protested it was impossible to include the Soviet Union in the plans for victory over Japan until the Soviets opened staff talks, Stalin assented. In early October 1944, the commanders of military forces in the Soviet Far East arrived in Moscow to begin staff talks with General John Deanne of the U.S. military mission. At the same time, Stalin informed Harriman that Soviet entry into the war against Japan would require American approval of certain political conditions about the future of Manchuria, a point about which he did not elaborate upon. On December 14, 1944, Stalin spelled out to Harriman what these political conditions were, namely that the Soviet Union be allowed to lease the Chinese Eastern Railroad and the ports on theLiaotung peninsula

The Liaodong Peninsula (also Liaotung Peninsula, ) is a peninsula in southern Liaoning province in Northeast China, and makes up the southwestern coastal half of the Liaodong region. It is located between the mouths of the Daliao River (the h ...

and for China to recognize the independence of Outer Mongolia.Buhite, Russell ''Decisions at Yalta'' p. 89. In a thinly veiled threat, Stalin boasted to Harriman that the flat open plains of Manchuria and northern China were the perfect country for Soviet combined arms operations, expressing much confidence that the Red Army would have no difficulty defeating the Kwantung Army

''Kantō-gun''

, image = Kwantung Army Headquarters.JPG

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Kwantung Army headquarters in Hsinking, Manchukuo

, dates = April ...

and that all of northern China would be under Soviet control once the Soviets declared war on Japan. Essentially, Stalin was saying the Soviets would take whatever they wanted in China, regardless if they had an agreement with the United States or not. At a dinner at the Kremlin during the visit of General de Gaulle to Moscow in December 1944, Harriman was disturbed by the way Stalin toasted Chief Air Marshal Alexander Novikov

Alexander Alexandrovich Novikov (russian: link=no, Алекса́ндр Алекса́ндрович Но́виков; – 3 December 1976) was the chief marshal of aviation for the Soviet Air Force during the Soviet Union's involvement in t ...

in front of him and de Gaulle, saying: "He has created a wonderful air force. But if he doesn't do his job properly then we'll kill him".

Yalta Conference

Harriman also attended theYalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post ...

, where he encouraged taking a stronger line with the Soviet Union—especially on questions of Poland. The American delegation at the Yalta conference stayed at the luxurious Livadia Palace

Livadia Palace (russian: Ливадийский дворец, uk, Лівадійський палац) is a former summer retreat of the last Russian tsar, Nicholas II, and his family in Livadiya, Crimea. The Yalta Conference was held there i ...

overlooking the Black Sea, and Harriman was given a room of his own to stay, a sign of presidential favor as most of the American delegation had to sleep five men to a room owing to a surplus of delegates and a lack of space in the Livadia Palace.Buhite, Russell ''Decisions at Yalta'' p. 7. The Livadia palace had been built in 1910–11 as a summer residence for the Emperor Nicholas II and his family, and was designed to house only 61 people, hence the presence of a 215-strong American delegation literally overwhelmed its facilities.

On February 8, 1945, Roosevelt, Harriman and Charles "Chip" Bohlen who served as the interpreter met Stalin, Molotov and the translator Vladimir Pavlov to discuss the Soviet entry into the war against Japan. During the meeting, it was agreed that the Kuriles

The Kuril Islands or Kurile Islands (; rus, Кури́льские острова́, r=Kuril'skiye ostrova, p=kʊˈrʲilʲskʲɪjə ɐstrɐˈva; Japanese: or ) are a volcanic archipelago currently administered as part of Sakhalin Oblast in th ...

islands and the southern half of Sakhalin

Sakhalin ( rus, Сахали́н, r=Sakhalín, p=səxɐˈlʲin; ja, 樺太 ''Karafuto''; zh, c=, p=Kùyèdǎo, s=库页岛, t=庫頁島; Manchu: ᠰᠠᡥᠠᠯᡳᠶᠠᠨ, ''Sahaliyan''; Orok: Бугата на̄, ''Bugata nā''; Nivkh ...

island were to be annexed by the Soviets. Without consulting Chiang, Roosevelt agreed to the Soviet demands for a role in managing the port of Dairen and to own the Chinese Eastern Railroad, through with the regard to the former he felt that Dairen should be internationalized. Roosevelt stated that he could not inform the Chinese at present because whatever was said to them "was known to the whole world in twenty-four hours", but he would tell them when the time was right; much to Harriman's mirth, Stalin promised he could "guarantee the security of the Supreme Soviet!" Once Molotov presented a draft note to Harriman about the future of Manchuria, Harriman complained that the Soviet draft stated the Soviet Union would lease both Dairen

Dalian () is a major sub-provincial port city in Liaoning province, People's Republic of China, and is Liaoning's second largest city (after the provincial capital Shenyang) and the third-most populous city of Northeast China. Located on the ...

and Port Arthur and manage not only the Chinese Eastern Railroad, but the South Manchuria Railroad as well.Buhite, Russell ''Decisions at Yalta'' p. 98. Harriman objected, stating that Roosevelt wanted the ports on the Liaotung peninsula to be internationalized, not leased by the Soviet Union and for the Manchurian railroads to be run jointly by a Sino-Soviet commission instead of being owned by the Soviet Union. Molotov agreed to Harriman's amendments, but when Churchill expressed his approval of Stalin's request for the Soviets to have a naval base at Port Arthur, the latter told Harriman that internationalization would not be possible for Port Arthur. The final draft called for the internationalization of Dairen with a leading role reserved for the Soviet Union; the Soviets to have a naval base at Port Arthur; a Sino-Soviet commission to run the railroads of Manchuria; and China to recognize Outer Mongolia.

On February 10, 1944, Harriman informed Stalin that Roosevelt had agreed to the British call for the "Big Four" to become the "Big Five" by including France.Buhite, Russell ''Decisions at Yalta'' p. 29. Specifically, the Americans were backing the British call to recognize France as one of the great powers of the post-war world and to allow the French to have an occupation zone in Germany. Through Stalin had been opposed to de Gaulle's claims for the French to have an occupation zone in Germany, the Anglo-American front on this issue, which was relatively unimportant to him, led him to tell Harriman that he now agreed on a four-power occupation of Germany. On February 11, 1945, the conference ended and the following day Harriman saw Roosevelt, his friend since childhood, for the last time, as he boarded a C-54 airplane at Saki airfield to take him to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

.Buhite, Russell ''Decisions at Yalta'' pp. 119–120. On April 12, 1945, Roosevelt died.

Deterioration of Soviet-American relationship after the war

At the Yalta conference, it was agreed that American prisoners captured by the Germans and liberated by the Soviets were to be immediately repatriated to American forces.Weinberg, Gerhard ''A World At Arms'' p. 808. The fact that the Soviets made many difficulties about fulfilling this promise such as not allowing American officers into Poland to contact American prisoners of war there led to frequent clashes between Harriman and Molotov, and contributed much to Harriman's increasing negative feelings about the Soviet Union. On May 11, 1945, Harriman reported in a cable to Washington that Stalin "feared a separate peace by ourselves with Japan" before the Soviet Union had moved its forces eastwards to take invade Manchuria. After Roosevelt's death, he attended the final "Big Three" conference at Potsdam. Although the new president, Harry Truman, was receptive to Harriman's anti-Soviet hard line advice, the new secretary of state, James Byrnes, managed to sideline him. While in Berlin, he noted the tight security imposed by Soviet military authorities and the beginnings of a program of reparations by which the Soviets were stripping out German industry. In 1945, while Ambassador to the Soviet Union, Harriman was presented with aTrojan Horse

The Trojan Horse was a wooden horse said to have been used by the Greeks during the Trojan War to enter the city of Troy and win the war. The Trojan Horse is not mentioned in Homer's ''Iliad'', with the poem ending before the war is concluded, ...

gift. In 1952, the gift, a carved wood Great Seal of the United States, which had adorned "the ambassador's Moscow residential office" in Spaso House, was found to be bugged.

Statesman of foreign and domestic affairs

Harriman served as ambassador to the Soviet Union until January 1946. When he returned to the United States, he worked hard to get

Harriman served as ambassador to the Soviet Union until January 1946. When he returned to the United States, he worked hard to get George Kennan

George Frost Kennan (February 16, 1904 – March 17, 2005) was an American diplomat and historian. He was best known as an advocate of a policy of containment of Soviet expansion during the Cold War. He lectured widely and wrote scholarly histo ...

's Long Telegram

The "X Article" is an article, formally titled "The Sources of Soviet Conduct", written by George F. Kennan and published under the pseudonym "X" in the July 1947 issue of ''Foreign Affairs'' magazine. The article widely introduced the term " ...

into wide distribution. Kennan's analysis, which generally accorded with Harriman's, became the cornerstone of Truman's Cold War strategy of containment.

From April to October 1946, he was ambassador to Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

, but he was soon appointed to become United States Secretary of Commerce

The United States secretary of commerce (SecCom) is the head of the United States Department of Commerce. The secretary serves as the principal advisor to the president of the United States on all matters relating to commerce. The secretary rep ...

under President Harry S. Truman to replace Henry A. Wallace

Henry Agard Wallace (October 7, 1888 – November 18, 1965) was an American politician, journalist, farmer, and businessman who served as the 33rd vice president of the United States, the 11th U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, and the 10th U.S. ...

, a critic of Truman's foreign policies. In 1948, he was put in charge of the Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred over $13 billion (equivalent of about $ in ) in economic re ...

. In Paris, he became friendly with the CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

agent Irving Brown

Irving Brown (Bronx, November 20, 1911 – Paris, February 10, 1989) was an American trade unionist and leader in the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and subsequently the AFL-CIO. Brown played a prominent role in Western Europe and Africa du ...

, who organised anti-communist unions and organisations.Harry Kelber"AFL-CIO's Dark Past"

November 22, 2004, on laboreducator.org

Frédéric Charpier

Frédéric and Frédérick are the French versions of the common male given name Frederick. They may refer to:

In artistry:

* Frédéric Back, Canadian award-winning animator

* Frédéric Bartholdi, French sculptor

* Frédéric Bazille, Impress ...

, ''La CIA en France. 60 ans d'ingérence dans les affaires françaises'', Seuil, 2008, p. 40–43. See alsLes belles aventures de la CIA en France

, January 8, 2008, ''

Bakchich Bakchich was a French news website founded in May 2006.

It has some articles translated into English. The chief editor was , a former reporter at the satirical weekly ''Le Canard enchaîné''. Its name finds its origin in the Arabic word "baksheesh ...

''. Harriman was then sent to Tehran

Tehran (; fa, تهران ) is the largest city in Tehran Province and the capital of Iran. With a population of around 9 million in the city and around 16 million in the larger metropolitan area of Greater Tehran, Tehran is the most popul ...

in July 1951 to mediate between Iran and Britain in the wake of the Iranian nationalization of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company

The Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC) was a British company founded in 1909 following the discovery of a large oil field in Masjed Soleiman, Persia (Iran). The British government purchased 51% of the company in 1914, gaining a controlling number ...

.

In 1949, the Defense Secretary James Forrestal

James Vincent Forrestal (February 15, 1892 – May 22, 1949) was the last Cabinet-level United States Secretary of the Navy and the first United States Secretary of Defense.

Forrestal came from a very strict middle-class Irish Catholic fami ...

committed suicide and afterwards Harriman and his wife Marie virtually adopted Forrestal's son Michael. Harriman paid tuition for Michael Forrestal when he attended Harvard Law School and made him make connections with New York's elite when he went into work at a law firm. Michael Forrestal served as a protege of Harriman's and later followed him into the Kennedy administration.

In the 1954 race to succeed Republican Thomas E. Dewey

Thomas Edmund Dewey (March 24, 1902 – March 16, 1971) was an American lawyer, prosecutor, and politician who served as the 47th governor of New York from 1943 to 1954. He was the Republican candidate for president in 1944 and 1948: although ...

as Governor of New York

The governor of New York is the head of government of the U.S. state of New York. The governor is the head of the executive branch of New York's state government and the commander-in-chief of the state's military forces. The governor h ...

, the Democratic Harriman defeated Dewey's protege, U.S. Senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and power ...

Irving M. Ives, by a tiny margin. He served as governor for one term until Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

Nelson Rockefeller

Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller (July 8, 1908 – January 26, 1979), sometimes referred to by his nickname Rocky, was an American businessman and politician who served as the 41st vice president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. A member of t ...

unseated him in 1958

Events

January

* January 1 – The European Economic Community (EEC) comes into being.

* January 3 – The West Indies Federation is formed.

* January 4

** Edmund Hillary's Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition completes the third ...

. As governor, he increased personal taxes by 11% but his tenure was dominated by his presidential ambitions. Harriman was a candidate for the Democratic Presidential Nomination in 1952, and again in 1956 when he was endorsed by Truman but lost (both times) to Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

governor Adlai Stevenson.

Despite the failure of his presidential ambitions, Harriman became a widely respected elder statesman of the party. Harriman's long friend Truman believed that the United States, which was a Protestant majority country, would never elect a Catholic president, which led him to oppose Senator John F. Kennedy in the 1960 Democratic primaries. Under Truman's influence, Harriman had been slow to endorse Kennedy, only doing so after it became clear that Kennedy was going to win the Democratic nomination. After Kennedy won the 1960 election, Harriman pressed hard for a position in the new Kennedy administration, which Kennedy younger brother and right-hand man Robert Kennedy opposed, saying that Harriman was too old and a latecomer to the Kennedy camp. However, after a luncheon, where Harriman recalled his service with Roosevelt and Truman, the elder Kennedy decided that Harriman's knowledge and experience might serve his administration well. Kennedy did make a condition: he told Harriman's adopted son, Michael Forrestal: "Averell's hearing is atrocious. If we're going to give him a job, he has to have a hearing aid, and I want you to see that he does".

In January 1961, he was appointed Ambassador at Large in the Kennedy administration, a position he held until November, when he became Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs. In 1961, at the suggestion of Ambassador Charles W. Yost

Charles Woodruff Yost (November 6, 1907 – May 21, 1981) was a career U.S. Ambassador who was assigned as his country's representative to the United Nations from 1969 to 1971.

Biography

Yost was born in Watertown, New York. He attended t ...

Harriman represented President Kennedy at the funeral of King Mohammed V of Morocco

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monoth ...

. During this period he advocated U.S. support of a neutral government in Laos

Laos (, ''Lāo'' )), officially the Lao People's Democratic Republic ( Lao: ສາທາລະນະລັດ ປະຊາທິປະໄຕ ປະຊາຊົນລາວ, French: République démocratique populaire lao), is a socialist s ...

and helped to negotiate the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty

The Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT) is the abbreviated name of the 1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, which prohibited all test detonations of nuclear weapons except for those conducted ...

in 1963.

During a visit to New Delhi to meet the Indian prime minister Nehru, Harriman met an exiled Lao Prince Souvanna Phouma