Vojislav Lukačević on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Vojislav Lukačević ( sr-cyr, Војислав Лукачевић; 1908 – 14 August 1945) was a

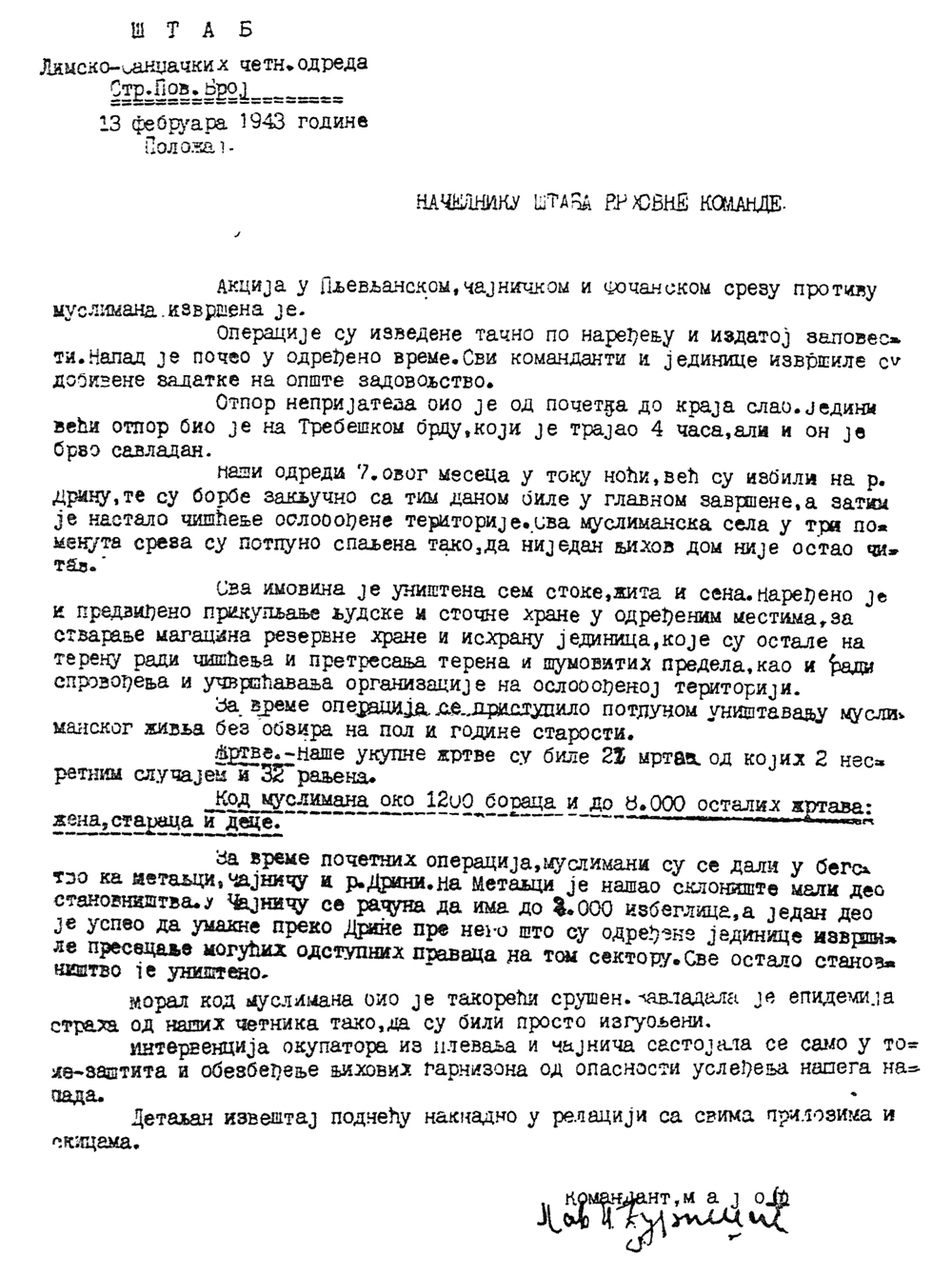

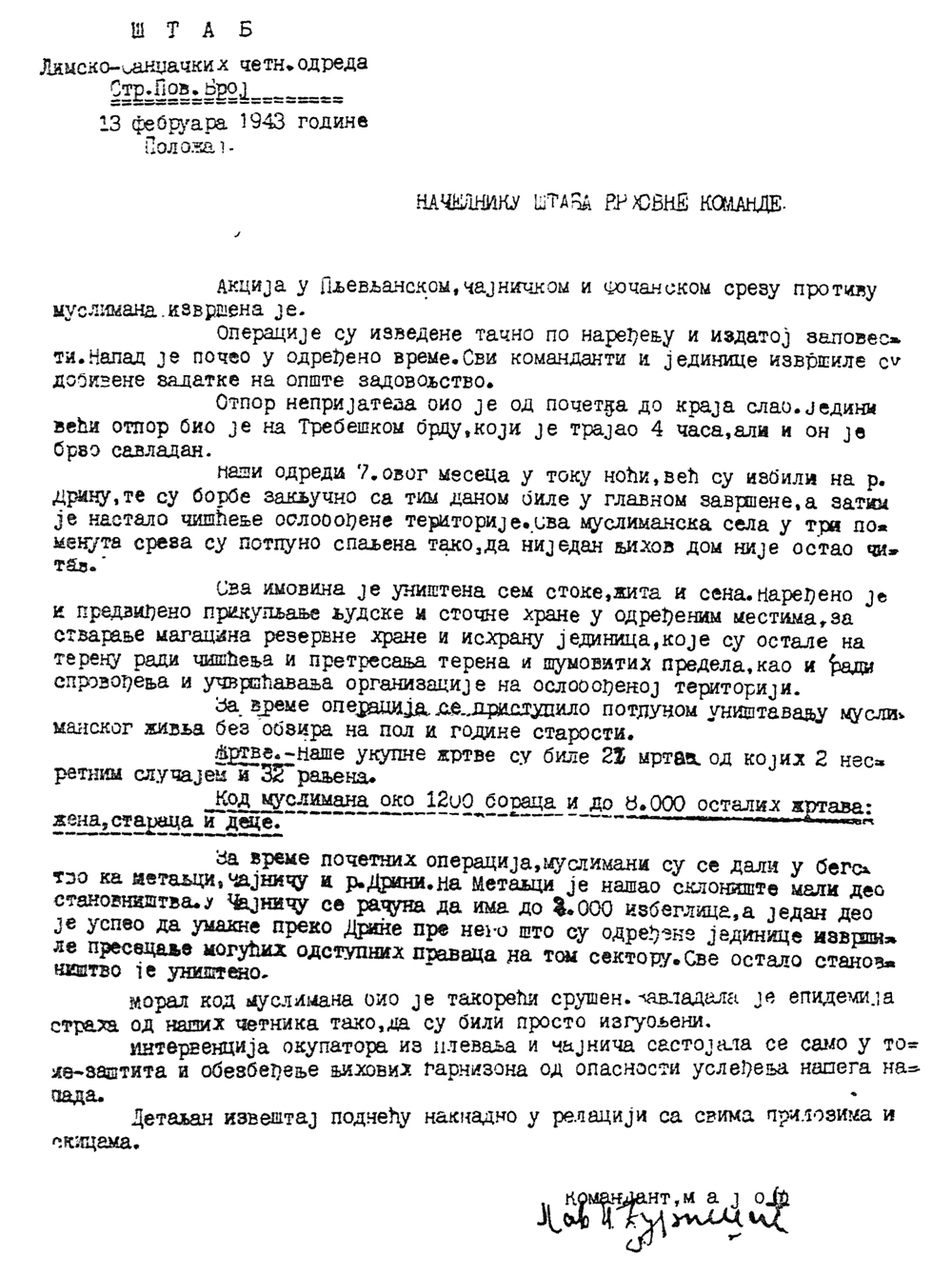

In early February 1943, during their advance northwest into Herzegovina in preparation for their involvement in Case White, the combined Chetnik force massacred large numbers of the Muslim population in the targeted areas. In a report to Mihailović dated 13 February 1943, Đurišić reported that the Chetnik forces under his command had killed about 1,200 Muslim combatants and about 8,000 old people, women, and children, and destroyed all property except for livestock, grain and hay, which they had seized. Đurišić reported that:

The orders for the "cleansing" operation stated that the Chetniks should kill all Muslim fighters, communists and Ustaše, but that they should not kill women and children. According to Pajović, these instructions were included to ensure there was no written evidence regarding the killing of non-combatants. On 8 February, one Chetnik commander made a notation on their copy of written orders issued by Đurišić that the detachments had received additional orders to kill all Muslims they encountered. On 10 February, Jovan Jelovac, the commander of the Pljevlja Brigade, who was subordinated to Lukačević, told one of his battalion commanders that he was to kill everyone, in accordance with the orders of their highest commanders. According to the historian Professor Jozo Tomasevich, despite Chetnik claims that this and previous "cleansing actions" were countermeasures against Muslim aggressive activities, all circumstances point to it being Đurišić's partial achievement of Mihailović's previous directive to clear the Sandžak of Muslims.

After first part of operations, Lukačević was given the duty to command the 'liberated territories'. In a meeting with Italian representative on February 10, Lukačević stated that his goal is to 'eliminate or expel all Muslims in Pljevlja and Čajniče Okrugs'. Muslim collaborationist leaders petitioned Italians to allow the return of Muslim refugees. Lukačević wrote to Italian command that if they handed him the refugees he would 'solve the problem with them in couple of hours', so Italians rejected Lukačević proposal and it was clear that Muslims won't return to their homes any time soon. First significant return was seen after

In early February 1943, during their advance northwest into Herzegovina in preparation for their involvement in Case White, the combined Chetnik force massacred large numbers of the Muslim population in the targeted areas. In a report to Mihailović dated 13 February 1943, Đurišić reported that the Chetnik forces under his command had killed about 1,200 Muslim combatants and about 8,000 old people, women, and children, and destroyed all property except for livestock, grain and hay, which they had seized. Đurišić reported that:

The orders for the "cleansing" operation stated that the Chetniks should kill all Muslim fighters, communists and Ustaše, but that they should not kill women and children. According to Pajović, these instructions were included to ensure there was no written evidence regarding the killing of non-combatants. On 8 February, one Chetnik commander made a notation on their copy of written orders issued by Đurišić that the detachments had received additional orders to kill all Muslims they encountered. On 10 February, Jovan Jelovac, the commander of the Pljevlja Brigade, who was subordinated to Lukačević, told one of his battalion commanders that he was to kill everyone, in accordance with the orders of their highest commanders. According to the historian Professor Jozo Tomasevich, despite Chetnik claims that this and previous "cleansing actions" were countermeasures against Muslim aggressive activities, all circumstances point to it being Đurišić's partial achievement of Mihailović's previous directive to clear the Sandžak of Muslims.

After first part of operations, Lukačević was given the duty to command the 'liberated territories'. In a meeting with Italian representative on February 10, Lukačević stated that his goal is to 'eliminate or expel all Muslims in Pljevlja and Čajniče Okrugs'. Muslim collaborationist leaders petitioned Italians to allow the return of Muslim refugees. Lukačević wrote to Italian command that if they handed him the refugees he would 'solve the problem with them in couple of hours', so Italians rejected Lukačević proposal and it was clear that Muslims won't return to their homes any time soon. First significant return was seen after

Serbian

Serbian may refer to:

* someone or something related to Serbia, a country in Southeastern Europe

* someone or something related to the Serbs, a South Slavic people

* Serbian language

* Serbian names

See also

*

*

* Old Serbian (disambiguation ...

Chetnik

The Chetniks ( sh-Cyrl-Latn, Четници, Četnici, ; sl, Četniki), formally the Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army, and also the Yugoslav Army in the Homeland and the Ravna Gora Movement, was a Yugoslav royalist and Serbian nation ...

commander in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Kraljevina Jugoslavija, Краљевина Југославија; sl, Kraljevina Jugoslavija) was a state in Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 until 1941. From 191 ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. At the outbreak of war, he held the rank of captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

of the reserves in the Royal Yugoslav Army

The Yugoslav Army ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, Jugoslovenska vojska, JV, Југословенска војска, ЈВ), commonly the Royal Yugoslav Army, was the land warfare military service branch of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (originally Kingdom of Serbs, ...

.

When the Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

invaded Yugoslavia in April 1941, Lukačević became a leader of Chetniks in the Sandžak

Sandžak (; sh, / , ; sq, Sanxhaku; ota, سنجاق, Sancak), also known as Sanjak, is a historical geo-political region in Serbia and Montenegro. The name Sandžak derives from the Sanjak of Novi Pazar, a former Ottoman administrative dis ...

region and joined the movement of Draža Mihailović

Dragoljub "Draža" Mihailović ( sr-Cyrl, Драгољуб Дража Михаиловић; 27 April 1893 – 17 July 1946) was a Yugoslav Serb general during World War II. He was the leader of the Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Ar ...

. While the Chetniks were an anti-Axis movement in their long-range goals and did engage in marginal resistance activities for limited periods, they also pursued almost throughout the war a tactical or selective collaboration

Collaboration (from Latin ''com-'' "with" + ''laborare'' "to labor", "to work") is the process of two or more people, entities or organizations working together to complete a task or achieve a goal. Collaboration is similar to cooperation. Most ...

with the occupation authorities against the Yugoslav Partisans

The Yugoslav Partisans,Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian, Slovene: , or the National Liberation Army, sh-Latn-Cyrl, Narodnooslobodilačka vojska (NOV), Народноослободилачка војска (НОВ); mk, Народноослобод� ...

. They engaged in cooperation with the Axis powers to one degree or another by establishing '' modi vivendi'' or operating as auxiliary forces under Axis control. Lukačević himself collaborated extensively with the Italians

, flag =

, flag_caption = The national flag of Italy

, population =

, regions = Italy 55,551,000

, region1 = Brazil

, pop1 = 25–33 million

, ref1 =

, region2 ...

and the Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

in actions against the Yugoslav Partisans until mid-1944.

In January and February 1943, while under the overall command of Major

Major ( commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicato ...

Pavle Đurišić

Pavle Đurišić ( sr-cyr, Павле Ђуришић, ; 9 July 1909 – April 1945) was a Montenegrin Serb regular officer of the Royal Yugoslav Army who became a Chetnik commander ('' vojvoda'') and led a significant proportion of the Chetniks ...

, Captain Lukačević and his Chetniks participated in several massacre

A massacre is the killing of a large number of people or animals, especially those who are not involved in any fighting or have no way of defending themselves. A massacre is generally considered to be morally unacceptable, especially when per ...

s of the Muslim population of Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and Pars pro toto#Geography, often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of Southern Europe, south and southeast Euro ...

, Herzegovina

Herzegovina ( or ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, Hercegovina, separator=" / ", Херцеговина, ) is the southern and smaller of two main geographical region of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the other being Bosnia. It has never had strictly defined geogra ...

and the Sandžak. Immediately after this, Lukačević and his Chetniks participated in one of the largest Axis anti-Partisan operations of the war, Case White

Case White (german: Fall Weiss), also known as the Fourth Enemy Offensive ( sh, Četvrta neprijateljska ofenziva/ofanziva), was a combined Axis strategic offensive launched against the Yugoslav Partisans throughout occupied Yugoslavia during ...

, where they fought alongside Italian, German and Croatian (NDH) troops. The following November, Lukačević concluded a formal collaboration agreement with the Germans and participated in a further anti-Partisan offensive, Operation Kugelblitz

Operation Kugelblitz ("ball lightning") was a major anti- Partisan offensive orchestrated by German forces in December 1943 during World War II in Yugoslavia. The Germans attacked Josip Broz Tito's Partisan forces in the eastern parts of the Ind ...

.

In February 1944, Lukačević travelled to London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

to represent Mihailović at the wedding of King Peter of Yugoslavia

Peter II ( sr-Cyrl, Петар II Карађорђевић, Petar II Karađorđević; 6 September 1923 – 3 November 1970) was the last king of Yugoslavia, reigning from October 1934 until his deposition in November 1945. He was the last r ...

. After returning to Yugoslavia in mid-1944, and in anticipation of an Allied landing on the Yugoslav coast, he decided to break with Mihailović and fight the Germans, but this was short-lived, as he was captured by the Partisans a few months later. After the war, he was tried for collaboration and war crimes and sentenced to death. He was executed

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

in August 1945.

Early life

Lukačević was born in 1908 inBelgrade

Belgrade ( , ;, ; names in other languages) is the capital and largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and the crossroads of the Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. Nearly 1,166,763 mi ...

, Kingdom of Serbia

The Kingdom of Serbia ( sr-cyr, Краљевина Србија, Kraljevina Srbija) was a country located in the Balkans which was created when the ruler of the Principality of Serbia, Milan I, was proclaimed king in 1882. Since 1817, the Prin ...

to a wealthy banking family. At one point, he was employed by the French civil engineering company ''Société de Construction des Batignolles

The Société de Construction des Batignolles was a civil engineering company of France created in 1871 as a public limited company from the 1846 limited partnership of ''Ernest Gouin et Cie.''. Initially founded to construct locomotives, the com ...

''. He attained the rank of captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

in the reserves of the Royal Yugoslav Army

The Yugoslav Army ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, Jugoslovenska vojska, JV, Југословенска војска, ЈВ), commonly the Royal Yugoslav Army, was the land warfare military service branch of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (originally Kingdom of Serbs, ...

before World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

.

Invasion and occupation

After the outbreak of World War II, the government ofRegent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

Prince Paul of Yugoslavia

Prince Paul of Yugoslavia, also known as Paul Karađorđević ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, Pavle Karađorđević, Павле Карађорђевић, English transliteration: ''Paul Karageorgevich''; 27 April 1893 – 14 September 1976), was prince regent o ...

declared its neutrality. Despite this, and with the aim of securing his southern flank for the pending attack on the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

began placing heavy pressure on the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Kraljevina Jugoslavija, Краљевина Југославија; sl, Kraljevina Jugoslavija) was a state in Southeast and Central Europe that existed from 1918 until 1941. From 191 ...

to sign the Tripartite Pact

The Tripartite Pact, also known as the Berlin Pact, was an agreement between Germany, Italy, and Japan signed in Berlin on 27 September 1940 by, respectively, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Galeazzo Ciano and Saburō Kurusu. It was a defensive milit ...

and join the Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

. After some delay, the Yugoslav government conditionally signed the Pact on 25 March 1941. Two days later a bloodless coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

deposed Prince Paul and declared 17-year-old Prince Peter II of Yugoslavia

Peter II ( sr-Cyrl, Петар II Карађорђевић, Petar II Karađorđević; 6 September 1923 – 3 November 1970) was the last king of Yugoslavia, reigning from October 1934 until his deposition in November 1945. He was the last ...

of age. Following the subsequent German-led invasion of Yugoslavia

The invasion of Yugoslavia, also known as the April War or Operation 25, or ''Projekt 25'' was a German-led attack on the Kingdom of Yugoslavia by the Axis powers which began on 6 April 1941 during World War II. The order for the invasion was ...

and the Yugoslav capitulation 11 days later, Lukačević went into hiding in the forests. He soon returned to Belgrade, where he became aware of the activities of Draža Mihailović

Dragoljub "Draža" Mihailović ( sr-Cyrl, Драгољуб Дража Михаиловић; 27 April 1893 – 17 July 1946) was a Yugoslav Serb general during World War II. He was the leader of the Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Ar ...

. He then left the capital with some other officers and soldiers to form a Chetnik

The Chetniks ( sh-Cyrl-Latn, Четници, Četnici, ; sl, Četniki), formally the Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army, and also the Yugoslav Army in the Homeland and the Ravna Gora Movement, was a Yugoslav royalist and Serbian nation ...

detachment in the Novi Pazar

Novi Pazar ( sr-cyr, Нови Пазар, lit. "New Bazaar"; ) is a city located in the Raška District of southwestern Serbia. As of the 2011 census, the urban area has 66,527 inhabitants, while the city administrative area has 100,410 inhabit ...

area of the Sandžak

Sandžak (; sh, / , ; sq, Sanxhaku; ota, سنجاق, Sancak), also known as Sanjak, is a historical geo-political region in Serbia and Montenegro. The name Sandžak derives from the Sanjak of Novi Pazar, a former Ottoman administrative dis ...

region. On 16 November 1941 Muslim forces from Novi Pazar

Novi Pazar ( sr-cyr, Нови Пазар, lit. "New Bazaar"; ) is a city located in the Raška District of southwestern Serbia. As of the 2011 census, the urban area has 66,527 inhabitants, while the city administrative area has 100,410 inhabit ...

and Albanian forces from Kosovo

Kosovo ( sq, Kosova or ; sr-Cyrl, Косово ), officially the Republic of Kosovo ( sq, Republika e Kosovës, links=no; sr, Република Косово, Republika Kosovo, links=no), is a international recognition of Kosovo, partiall ...

attacked Raška and quickly advanced toward the town. They were commanded by Aćif Hadžiahmetović. The situation for the defenders became very difficult, so Lukačević personally engaged himself in the defence of the town. On 17 November they stopped the advance of Hadžiahmetović's forces and forced them to retreat. On 21 November Lukačević took part in the attack of Chetnik forces on Novi Pazar. In the summer of 1942, Lukačević and his Chetniks fought the Partisans in Herzegovina

Herzegovina ( or ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, Hercegovina, separator=" / ", Херцеговина, ) is the southern and smaller of two main geographical region of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the other being Bosnia. It has never had strictly defined geogra ...

. In October Lukačević personally leads a unit in wider operations against remnants of Yugoslav Partisans

The Yugoslav Partisans,Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian, Slovene: , or the National Liberation Army, sh-Latn-Cyrl, Narodnooslobodilačka vojska (NOV), Народноослободилачка војска (НОВ); mk, Народноослобод� ...

in Srez of Pljevlja

Pljevlja ( srp, Пљевља, ) is a town and the center of Pljevlja Municipality located in the northern part of Montenegro. The town lies at an altitude of . In the Middle Ages, Pljevlja had been a crossroad of the important commercial roads an ...

. In caves near village of Dobrilovana, his unit kills 2 and captures 12 communists. Captured ones are handed over to Chetnik command in Kolašin

Kolašin (Montenegrin Cyrillic: Колашин, ) is a town in northern Montenegro. It has a population of 2,989 (2003 census). Kolašin is the centre of Kolašin Municipality (population 9,949) and an unofficial centre of Morača region, named af ...

. These operations almost completely eliminate partisan presence in Pljevlja region.

Massacres of Muslims

In December 1942, Chetniks fromMontenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = ...

and Sandžak met at a conference in the village of Šahovići near Bijelo Polje

Bijelo Polje ( cnr, Бијело Поље, ) is a town in northeastern Montenegro on the Lim River. It has an urban population of 15,400 (2011 census). It is the administrative, economic, cultural and educational centre of northern Montenegro.

...

. The conference was dominated by Montenegrin Serb

Serbs of Montenegro ( sr, / ) or Montenegrin Serbs ( sr, / ),, meaning "Montenegrin Serbs", and meaning "Serbs Montenegrins". Specifically, Their regional autonym is simply , literal meaning "Montenegrins",Charles Seignobos, Political Histo ...

Chetnik commander Major

Major ( commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicato ...

Pavle Đurišić

Pavle Đurišić ( sr-cyr, Павле Ђуришић, ; 9 July 1909 – April 1945) was a Montenegrin Serb regular officer of the Royal Yugoslav Army who became a Chetnik commander ('' vojvoda'') and led a significant proportion of the Chetniks ...

and its resolutions expressed extremism and intolerance, as well as an agenda which focused on restoring the pre-war ''status quo

is a Latin phrase meaning the existing state of affairs, particularly with regard to social, political, religious or military issues. In the sociological sense, the ''status quo'' refers to the current state of social structure and/or values. ...

'' in Yugoslavia implemented in its initial stages by a Chetnik dictatorship. It also laid claim to parts of the territory of Yugoslavia's neighbors. At this conference, Mihailović was represented by his chief of staff, Major Zaharije Ostojić

Lieutenant Colonel Zaharije Ostojić ( sr-cyr, Захарије Остојић; 1907 – April 1945) was a Montenegrin Serb and Yugoslav military officer who served as the chief of the operational, organisational and intelligence branches o ...

, who had previously been encouraged by Mihailović to wage a campaign of terror against the Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

population living along the borders of Montenegro and the Sandžak.

The conference decided to destroy the Muslim villages in the Čajniče

Čajniče ( sr-cyr, Чајниче, ) is a town and municipality located in Republika Srpska, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. As of 2013, the town has a population of 2,401 inhabitants, while the municipality has 4,895 inhabitants.

Settlemen ...

district of Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and Pars pro toto#Geography, often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of Southern Europe, south and southeast Euro ...

. On 3 January 1943, Ostojić issued orders to "cleanse" the Čajniče district of Ustaše

The Ustaše (), also known by anglicised versions Ustasha or Ustashe, was a Croats, Croatian Fascism, fascist and ultranationalism, ultranationalist organization active, as one organization, between 1929 and 1945, formally known as the Ustaš ...

-Muslim organisations. According to the historian Radoje Pajović, Ostojić produced a detailed plan which avoided specifying what would be done with the Muslim population of the district. Instead, these instructions were to be given orally to the responsible commanders. Delays in the movement of Chetnik forces into Bosnia to participate in the anti-Partisan Case White

Case White (german: Fall Weiss), also known as the Fourth Enemy Offensive ( sh, Četvrta neprijateljska ofenziva/ofanziva), was a combined Axis strategic offensive launched against the Yugoslav Partisans throughout occupied Yugoslavia during ...

offensive alongside the Italians enabled Chetnik Supreme Command to expand the planned "cleansing" operation to include the Pljevlja

Pljevlja ( srp, Пљевља, ) is a town and the center of Pljevlja Municipality located in the northern part of Montenegro. The town lies at an altitude of . In the Middle Ages, Pljevlja had been a crossroad of the important commercial roads an ...

district in the Sandžak and the Foča

Foča ( sr-Cyrl, Фоча, ) is a town and a municipality located in Republika Srpska in south-eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina, on the banks of Drina river. As of 2013, the town has a population of 12,234 inhabitants, while the municipality has 1 ...

district of Bosnia. A combined Chetnik force of 6,000 was assembled, divided into four detachments, each with its own commander. Lukačević commanded a force of 1,600, consisting of Chetniks from Višegrad

Višegrad ( sr-cyrl, Вишеград, ) is a town and municipality located in eastern Republika Srpska, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It rests at the confluence of the Drina and the Rzav river. As of 2013, it has a population of 10,668 ...

, Priboj

Priboj ( sr-Cyrl, Прибој, ) is a town and municipality located in the Zlatibor District of southwestern Serbia. The population of the town is 14,920, while the population of the municipality is 27,133.

Geography

The municipality of Priboj i ...

, Nova Varoš, Prijepolje

Prijepolje ( sr-cyr, Пријепоље, ) is a town and municipality located in the Zlatibor District of southwestern Serbia. As of 2011 census, the town has 13,330 inhabitants, while the municipality has 37,059 inhabitants.

Etymology

One possibl ...

, Pljevlja and Bijelo Polje. His force formed one of the four detachments, and Mihailović ordered that all four detachments be placed under the overall command of Đurišić.

In early February 1943, during their advance northwest into Herzegovina in preparation for their involvement in Case White, the combined Chetnik force massacred large numbers of the Muslim population in the targeted areas. In a report to Mihailović dated 13 February 1943, Đurišić reported that the Chetnik forces under his command had killed about 1,200 Muslim combatants and about 8,000 old people, women, and children, and destroyed all property except for livestock, grain and hay, which they had seized. Đurišić reported that:

The orders for the "cleansing" operation stated that the Chetniks should kill all Muslim fighters, communists and Ustaše, but that they should not kill women and children. According to Pajović, these instructions were included to ensure there was no written evidence regarding the killing of non-combatants. On 8 February, one Chetnik commander made a notation on their copy of written orders issued by Đurišić that the detachments had received additional orders to kill all Muslims they encountered. On 10 February, Jovan Jelovac, the commander of the Pljevlja Brigade, who was subordinated to Lukačević, told one of his battalion commanders that he was to kill everyone, in accordance with the orders of their highest commanders. According to the historian Professor Jozo Tomasevich, despite Chetnik claims that this and previous "cleansing actions" were countermeasures against Muslim aggressive activities, all circumstances point to it being Đurišić's partial achievement of Mihailović's previous directive to clear the Sandžak of Muslims.

After first part of operations, Lukačević was given the duty to command the 'liberated territories'. In a meeting with Italian representative on February 10, Lukačević stated that his goal is to 'eliminate or expel all Muslims in Pljevlja and Čajniče Okrugs'. Muslim collaborationist leaders petitioned Italians to allow the return of Muslim refugees. Lukačević wrote to Italian command that if they handed him the refugees he would 'solve the problem with them in couple of hours', so Italians rejected Lukačević proposal and it was clear that Muslims won't return to their homes any time soon. First significant return was seen after

In early February 1943, during their advance northwest into Herzegovina in preparation for their involvement in Case White, the combined Chetnik force massacred large numbers of the Muslim population in the targeted areas. In a report to Mihailović dated 13 February 1943, Đurišić reported that the Chetnik forces under his command had killed about 1,200 Muslim combatants and about 8,000 old people, women, and children, and destroyed all property except for livestock, grain and hay, which they had seized. Đurišić reported that:

The orders for the "cleansing" operation stated that the Chetniks should kill all Muslim fighters, communists and Ustaše, but that they should not kill women and children. According to Pajović, these instructions were included to ensure there was no written evidence regarding the killing of non-combatants. On 8 February, one Chetnik commander made a notation on their copy of written orders issued by Đurišić that the detachments had received additional orders to kill all Muslims they encountered. On 10 February, Jovan Jelovac, the commander of the Pljevlja Brigade, who was subordinated to Lukačević, told one of his battalion commanders that he was to kill everyone, in accordance with the orders of their highest commanders. According to the historian Professor Jozo Tomasevich, despite Chetnik claims that this and previous "cleansing actions" were countermeasures against Muslim aggressive activities, all circumstances point to it being Đurišić's partial achievement of Mihailović's previous directive to clear the Sandžak of Muslims.

After first part of operations, Lukačević was given the duty to command the 'liberated territories'. In a meeting with Italian representative on February 10, Lukačević stated that his goal is to 'eliminate or expel all Muslims in Pljevlja and Čajniče Okrugs'. Muslim collaborationist leaders petitioned Italians to allow the return of Muslim refugees. Lukačević wrote to Italian command that if they handed him the refugees he would 'solve the problem with them in couple of hours', so Italians rejected Lukačević proposal and it was clear that Muslims won't return to their homes any time soon. First significant return was seen after Case Black

Case Black (german: Fall Schwarz), also known as the Fifth Enemy Offensive ( sh-Latn, Peta neprijateljska ofanziva) in Yugoslav historiography and often identified with its final phase, the Battle of the Sutjeska ( sh-Latn, Bitka na Sutjesci ) ...

in June 1943, as it weakened Chetnik

The Chetniks ( sh-Cyrl-Latn, Четници, Četnici, ; sl, Četniki), formally the Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army, and also the Yugoslav Army in the Homeland and the Ravna Gora Movement, was a Yugoslav royalist and Serbian nation ...

forces in the region, but Lukačević still had orders to prevent return of Muslims in his area of command.

Case White

Lukačević and his Chetniks were drawn into closer collaboration with the Axis during the second phase of Case White, which took place in the Neretva and Rama river valleys in late February 1943 and was one of the largest anti-Partisan offensives of the war. Despite the fact that the Chetniks were an anti-Axis movement in their long-range goals and did engage in marginal resistance activities for limited periods, their involvement in Case White is one of the most significant examples of their tactical or selective collaboration with the Axis occupation forces. In this instance, the participating Chetniks received Italian logistic support and included those operating as legalised auxiliary forces under Italian control. During this offensive, between 12,000 and 15,000 Chetniks fought alongside Italian forces, and Lukačević and his Chetniks also fought alongside German and Croatian troops against the Partisans. In February 1943, during the second phase of Case White, Lukačević and his Chetniks jointly held the town ofKonjic

Konjic ( sr-Cyrl, Коњиц) is a city and municipality located in Herzegovina-Neretva Canton of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is located in northern Herzegovina, around southwest of Saraje ...

on the Neretva

The Neretva ( sr-cyrl, Неретва, ), also known as Narenta, is one of the largest rivers of the eastern part of the Adriatic basin. Four HE power-plants with large dams (higher than 150,5 metres) provide flood protection, power and water s ...

river alongside Italian troops. After being reinforced by German and NDH troops and some additional Chetniks, the combined force held the town against concerted attacks by the Partisans over a seven-day period. The first attack was launched by two battalions of the 1st Proletarian Division on 19 February and was followed by repeated attacks by the 3rd Assault Division between 22 and 26 February. Unable to capture the town and its critical bridge across the Neretva, the Partisans eventually crossed the river downstream at Jablanica. Ostojić was aware of Lukačević's collaboration with the Germans and NDH troops at Konjic but, at his trial, Mihailović denied that he himself was aware of it, claiming that Ostojić controlled the communications links and kept the information from him. During the fighting at Konjic, the Germans also supplied Lukačević's troops with ammunition. Both Ostojić and Lukačević were highly critical of what they described as Mihailović's bold but reckless tactics

Tactic(s) or Tactical may refer to:

* Tactic (method), a conceptual action implemented as one or more specific tasks

** Military tactics, the disposition and maneuver of units on a particular sea or battlefield

** Chess tactics

** Political tact ...

during Case White, indicating that Mihailović was largely responsible for the Chetnik failure to hold the Partisans at the Neretva.

In September 1943, immediately following the Italian capitulation, the Italian Venezia Division, which was garrisoned at Berane

Berane ( cyrl, Беране) is one of the largest towns of northeastern Montenegro and a former administrative centre of the Ivangrad District. The town is located on the Lim river. From 1949 to 1992, it was named Ivangrad ( cyrl, Иванг� ...

, surrendered to the British Special Operations Executive

The Special Operations Executive (SOE) was a secret British World War II organisation. It was officially formed on 22 July 1940 under Minister of Economic Warfare Hugh Dalton, from the amalgamation of three existing secret organisations. Its p ...

Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

S.W. "Bill" Bailey and Major Lukačević, but Lukačević and his troops were unable to control the surrendered Italians. Partisan formations arrived in Berane shortly afterward and were able to convince the Italians to join them.

Collaboration with the Germans

In September 1943,United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colon ...

Albert B. Seitz and Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

George Musulin

George "Guv" S. Musulin (April 9, 1914 – February 23, 1987) was an American army officer of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) who in 1950 became a CIA operative.

Early life

George Musulin was born into a Serbian family in New York City ...

parachuted into the Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia, along with British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

Brigadier

Brigadier is a military rank, the seniority of which depends on the country. In some countries, it is a senior rank above colonel, equivalent to a brigadier general or commodore, typically commanding a brigade of several thousand soldiers. ...

Charles Armstrong. In November, Seitz and another American liaison officer, Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Walter R. Mansfield

Walter Roe Mansfield (July 1, 1911 – January 8, 1987) was a United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit and previously was a United States District Judge of the United States District Court for the So ...

, conducted a tour of inspection of Chetnik areas, including that of Lukačević. During their tour they witnessed fighting between Chetniks and Partisans. Due to their relative freedom of movement, the Americans assumed that the Chetniks controlled the territory they moved through. However, despite the praise that Seitz expressed for Lukačević, the Chetnik leader was collaborating with the Germans at the same time that he was hosting the visiting Americans.

In mid-November 1943, Major Lukačević was the chief of the Chetnik detachments based near Stari Ras

Ras ( sr-Cyrl, Рас; lat, Arsa), known in modern Serbian historiography as Stari Ras ( sr-Cyrl, Стари Рас, "Old Ras"), is a medieval fortress located in the vicinity of former market-place of ''Staro Trgovište'', some 11 km wes ...

, near Novi Pazar in the Sandžak. On 13 November, his representative concluded a formal collaboration agreement (german: Waffenruhe-Verträge) with the representative of the German Military Commander in southeast Europe, ''General der Infanterie General of the Infantry is a military rank of a General officer in the infantry and refers to:

* General of the Infantry (Austria)

* General of the Infantry (Bulgaria)

* General of the Infantry (Germany) ('), a rank of a general in the German Imp ...

'' (Lieutenant General) Hans Felber

__NOTOC__

Hans-Gustav Felber (July 8, 1889 – March 8, 1962) was a general in the Wehrmacht of Nazi Germany during World War II.

Biography

From 15 October 1939 Felber was the chief of staff of the 2nd Army, becoming chief of staff of the Army ...

. The agreement was signed on 19 November, and covered a large portion of the Sandžak and the Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia, bounded by Bajina Bašta

Bajina Bašta ( sr-cyr, Бајина Башта, ) is a town and municipality located in the Zlatibor District of western Serbia. The town lies in the valley of the Drina river at the eastern edge of Tara National Park.

The population of the to ...

, the Drina

The Drina ( sr-Cyrl, Дрина, ) is a long Balkans river, which forms a large portion of the border between Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia. It is the longest tributary of the Sava River and the longest karst river in the Dinaric Alps whi ...

river, the Tara river, Bijelo Polje, Rožaje

Rožaje ( cnr, Рожаје, bs, Rožaje), ; sq, Rozhajë) is a town in northeastern Montenegro.

As of 2011, the city has a population of 9,567 inhabitants.

Surrounded by hills to its west and mountains to its east (notably Mount Hajla), the ...

, Kosovska Mitrovica

Mitrovica ( sq-definite, Mitrovicë; sr-cyrl, Митровица) or Kosovska Mitrovica ( sr-cyrl, Косовска Митровица) is a city and municipality located in Kosovo. Settled on the banks of Ibar and Sitnica rivers, the city is ...

, the Ibar Ibar may refer to:

People

* Ibar of Beggerin (died 500), Irish saint

* Íbar of Killibar Beg, Irish saint

* Hilmi Ibar (born 1947), Kosovar academic

* José Ibar (born 1969), Cuban baseball player

Places

* Ibar District, a division of the Serbia ...

river, Kraljevo

Kraljevo ( sr-cyr, Краљево, ) is a List of cities in Serbia, city and the administrative center of the Raška District in central Serbia. It is situated on the confluence of West Morava and Ibar River, Ibar, in the geographical region of � ...

, Čačak

Čačak ( sr-Cyrl, Чачак, ) is a city and the administrative center of the Moravica District in central Serbia. It is located in the West Morava Valley within the geographical region of Šumadija. , the city proper has 73,331 inhabitants, wh ...

and Užice

Užice ( sr-cyr, Ужице, ) is a city and the administrative centre of the Zlatibor District in western Serbia. It is located on the banks of the river Đetinja. According to the 2011 census, the city proper has a population of 59,747. The C ...

. Under the agreement, a special German liaison officer was assigned to Lukačević to advise on tactics, ensure cooperation, and facilitate arms and ammunition supply. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

read the decrypted text of the agreement between Lukačević and Felber, which had a significant influence on the changing attitude of the British towards Mihailović.

In early December 1943, Lukačević's Chetniks participated in Operation Kugelblitz

Operation Kugelblitz ("ball lightning") was a major anti- Partisan offensive orchestrated by German forces in December 1943 during World War II in Yugoslavia. The Germans attacked Josip Broz Tito's Partisan forces in the eastern parts of the Ind ...

, the first of a series of German operations alongside the 1st Mountain Division, 7th SS Volunteer Mountain Division Prinz Eugen

The 7th SS Volunteer Mountain Division "Prinz Eugen" (), initially named the SS-Volunteer Division ''Prinz Eugen'' (''SS-Freiwilligen-Division "Prinz Eugen"''), was a mountain infantry division of the Waffen-SS, an armed branch of the German Naz ...

, and parts of the 187th Reserve Division, the 369th (Croatian) Infantry Division

The 369th (Croatian) Infantry Division (german: 369. (Kroatische) Infanterie-Division, hr, 369. (hrvatska) pješačka divizija) was a legionary division of the German Army (Wehrmacht) during World War II.

It was formed with Croat volunteers from ...

and the 24th Bulgarian Division. The Partisans avoided decisive engagement and the operation concluded on 18 December. Also during December, the Higher SS and Police Leader in the Sandžak, ''SS-Standartenführer

__NOTOC__

''Standartenführer'' (short: ''Staf'', , ) was a Nazi Party (NSDAP) paramilitary rank that was used in several NSDAP organizations, such as the SA, SS, NSKK and the NSFK. First founded as a title in 1925, in 1928 it became one of ...

'' Karl von Krempler

Karl von Krempler, later only Karl Krempler (Serbian Cyrillic: ''Карл Кремплер'', 26 May 1896 – 17 April 1971) was a German SS-''Standartenführer'' and SS and Police Leader during the Nazi era. In World War II, he was responsible ...

, posted notices authorising local Serbs to join Lukačević's Chetniks. On 22 December, shortly after the conclusion of Operation Kugelblitz, ''Oberst

''Oberst'' () is a senior field officer rank in several German-speaking and Scandinavian countries, equivalent to colonel. It is currently used by both the ground and air forces of Austria, Germany, Switzerland, Denmark, and Norway. The Swedish ...

'' (Colonel) Josef Remold issued an order of the day commending Lukačević for his enthusiasm in fighting the Partisans in the Sandžak, and allowed him to keep some of the arms he had captured.

Break with Mihailović

In mid-February 1944, Lukačević, Baćović and another officer accompanied Bailey to the coast south ofDubrovnik

Dubrovnik (), historically known as Ragusa (; see notes on naming), is a city on the Adriatic Sea in the region of Dalmatia, in the southeastern semi-exclave of Croatia. It is one of the most prominent tourist destinations in the Mediterranea ...

and were evacuated from Cavtat

Cavtat (, it, Ragusa Vecchia, lit=Old Ragusa) is a village in the Dubrovnik-Neretva County of Croatia. It is on the Adriatic Sea coast south of Dubrovnik and is the centre of the Konavle municipality.

History

Antiquity

The original city wa ...

by a Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-ste ...

. Their passage through German-occupied territory was probably facilitated by Lukačević's accommodation with the Germans. At one point, Lukačević was invited to have a meal with the German garrison commander of a nearby town, but declined the offer. Lukačević and the others then travelled via Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

to London, where Lukačević represented Mihailović at King Peter's wedding on 20 March 1944. After the British government

ga, Rialtas a Shoilse gd, Riaghaltas a Mhòrachd

, image = HM Government logo.svg

, image_size = 220px

, image2 = Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (HM Government).svg

, image_size2 = 180px

, caption = Royal Arms

, date_est ...

decided to withdraw support from Mihailović, Lukačević and his Chetnik companions were not allowed to return to Yugoslavia until the British mission to Mihailović headed by Armstrong had been safely evacuated from occupied territory. Lukačević and the others were detained by the British in Bari

Bari ( , ; nap, label= Barese, Bare ; lat, Barium) is the capital city of the Metropolitan City of Bari and of the Apulia region, on the Adriatic Sea, southern Italy. It is the second most important economic centre of mainland Southern Ital ...

and thoroughly searched by local authorities, who suspected them of a robbery that had occurred in the Yugoslav consulate in Cairo a short time before. Most of the money, jewelry and uncensored letters that they were carrying were impounded. The men were flown out of Bari on 30 May, and landed on an improvised airfield at Pranjani

Pranjani is a village in the Municipalities of Serbia, municipality of Gornji Milanovac, Serbia. In 1944, Pranjani was the site of Operation Halyard.

In 2019, a small wooden guest house was transfer by truck to a new location, in the churchyard, w ...

northwest of Čačak shortly after. Because their landing at Pranjani coincided with Armstrong's departure, Lukačević and Baćović demanded that Armstrong be held as a hostage until their impounded belongings could be returned from Bari. The Chetniks at the airfield refused to keep Armstrong any further, and he was allowed to depart without incident.

In mid-1944, after Mihailović was removed from his post as Minister of the Army, Navy and Air Force as a result of the dismissal of the Purić government by King Peter, Lukačević attempted to independently contact the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

in Italy in the hope of "reaching an understanding on a common fight against the enemy". When these attempts failed, Lukačević announced in August 1944 that he and other Chetnik commanders in eastern Bosnia, eastern Herzegovina and Sandžak were no longer obeying orders from Mihailović, and were forming an independent resistance movement to fight the occupiers and those collaborating with them. In early September, he issued a proclamation to the people explaining his reasons for attacking the Germans. On 19 October, Lukačević proposed that the Chetniks change their policy to greet the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

as liberators and ask to be taken under the command of a Russian general. He also tried to arrange a non-aggression pact

A non-aggression pact or neutrality pact is a treaty between two or more states/countries that includes a promise by the signatories not to engage in military action against each other. Such treaties may be described by other names, such as a tr ...

with the Partisans. Subsequently, he deployed his 4,500 Chetniks into southern Herzegovina and for several days from 22 September they attacked the 369th (Croatian) Infantry Division and the Trebinje

Trebinje ( sr-Cyrl, Требиње, ) is a city and municipality located in the Republika Srpska entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is the southernmost city in Bosnia and Herzegovina and is situated on the banks of Trebišnjica river in the r ...

–Dubrovnik railway line, capturing some villages and taking hundreds of prisoners. Mihailović formally relieved Lukačević of his command and asked other Chetnik commanders to act against him. However, the Partisans, concerned Lukačević was trying to link up with a feared British landing on the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to the ...

coast, attacked his forces on 25 September, first capturing his stronghold at Bileća

Bileća ( sr-cyrl, Билећа) is a town and municipality located in Republika Srpska, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. As of 2013, the town has a population of 7,476 inhabitants, while the municipality has 10,807 inhabitants.

History

...

and then comprehensively defeating him. With several hundred remaining Chetniks, Lukačević withdrew as far as Foča before returning to the Bileća area in the hope of linking up with small detachments of British troops that had been landed to support Partisan operations. Instead he was captured by the Partisans.

Trial and execution

Lukačević, along with other defendants, was tried by a military court in Belgrade between 28 July and 9 August 1945. He was accused of conducting the massacre at Foča, participating in the extermination of the Muslim population, collaboration with the occupying forces and the Serbian puppet government of GeneralMilan Nedić

Milan Nedić ( sr-Cyrl, Милан Недић; 2 September 1878 – 4 February 1946) was a Yugoslav and Serbian army general and politician who served as the chief of the General Staff of the Royal Yugoslav Army and minister of war in the R ...

and the commission of crimes against the Partisans. He was found guilty of various offences and executed by firing squad on 14 August 1945.

Footnotes

References

Books

* * * * * * * * *Journals

* *Documents

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Lukacevic, Vojislav 1908 births 1945 deaths Military personnel from Belgrade People from the Kingdom of Serbia Serbian people of World War II Chetnik personnel of World War II Serbian anti-communists Serbian collaborators with Fascist Italy Serbian collaborators with Nazi Germany Serbian people convicted of war crimes Royal Yugoslav Army personnel of World War II Executed Serbian people Executed Yugoslav collaborators with Nazi Germany People executed by Yugoslavia by firing squad Serbian mass murderers Executed mass murderers