Vladimir Horowitz on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Vladimir Samoylovich Horowitz; yi, וולאַדימיר סאַמוילאָוויטש האָראָוויץ, group=n (November 5, 1989)Schonberg, 1992 was a

Vladimir Samoylovich Horowitz; yi, וולאַדימיר סאַמוילאָוויטש האָראָוויץ, group=n (November 5, 1989)Schonberg, 1992 was a

Horowitz was born on October 1, 1903, in

Horowitz was born on October 1, 1903, in

On December 18, 1925, Horowitz made his first appearance outside his home country, in

On December 18, 1925, Horowitz made his first appearance outside his home country, in

accessed ''15 January 2010'' He made his television debut in a concert taped at Carnegie Hall on February 1, 1968, and broadcast nationwide by CBS on September 22 of that year. Despite rapturous receptions at recitals, Horowitz became increasingly unsure of his abilities as a pianist. On several occasions, the pianist had to be pushed onto the stage. He suffered from depression and withdrew from public performances from 1936 to 1938, 1953 to 1965, 1969 to 1974, and 1983 to 1985.

In 1933, in a civil ceremony, Horowitz married

In 1933, in a civil ceremony, Horowitz married

In 1985, Horowitz, no longer taking medication or drinking alcohol, returned to performing and recording. His first post-retirement appearance was not on stage, but in the documentary film '' Vladimir Horowitz: The Last Romantic''. In many of his later performances, the octogenarian pianist substituted finesse and coloration for bravura, although he was still capable of remarkable technical feats. Many critics, including

In 1985, Horowitz, no longer taking medication or drinking alcohol, returned to performing and recording. His first post-retirement appearance was not on stage, but in the documentary film '' Vladimir Horowitz: The Last Romantic''. In many of his later performances, the octogenarian pianist substituted finesse and coloration for bravura, although he was still capable of remarkable technical feats. Many critics, including

Horowitz is best known for his performances of the Romantic piano repertoire. Many consider Horowitz's first recording of the Liszt Sonata in B minor in 1932 to be the definitive reading of that piece, even after over 80 years and more than 100 performances committed to disc by other pianists. Other pieces with which he was closely associated were Scriabin's Étude in D-sharp minor, Chopin's Ballade No. 1, and many Rachmaninoff miniatures, including ''

Horowitz is best known for his performances of the Romantic piano repertoire. Many consider Horowitz's first recording of the Liszt Sonata in B minor in 1932 to be the definitive reading of that piece, even after over 80 years and more than 100 performances committed to disc by other pianists. Other pieces with which he was closely associated were Scriabin's Étude in D-sharp minor, Chopin's Ballade No. 1, and many Rachmaninoff miniatures, including ''

''Horowitz: A Biography of Vladimir Horowitz.''

UK: Macdonald. *

The Horowitz Papers

at the Irving S. Gilmore Music Library, Yale University

Vladimir Horowitz website at Sony Classical

Vladimir Horowitz at Deutsche Grammophon

Vladimir Horowitz at Encyclopædia Britannica

* *

Entry at 45worlds.com

{{DEFAULTSORT:Horowitz, Vladimir 1903 births 1989 deaths 20th-century American composers 20th-century American male musicians 20th-century classical composers 20th-century classical pianists 20th-century LGBT people 20th-century Russian male musicians 20th-century Ukrainian musicians American classical composers American classical pianists American male classical composers American male classical pianists American people of Russian-Jewish descent American people of Ukrainian-Jewish descent Burials at the Cimitero Monumentale di Milano Deutsche Grammophon artists American gay musicians Grammy Award winners Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners Grand Crosses with Star and Sash of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany Honorary Members of the Royal Academy of Music Jewish American classical composers Jewish American classical musicians Jewish classical pianists Jewish Ukrainian musicians LGBT classical composers LGBT classical musicians LGBT Jews LGBT musicians from Russia LGBT people from Ukraine Music & Arts artists Musicians from Kyiv People from Kiev Governorate Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients Recipients of the Legion of Honour Recipients of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic Royal Philharmonic Society Gold Medallists Russian classical composers Russian classical pianists Russian Jews Russian male classical composers Soviet classical composers Soviet classical pianists Soviet emigrants to the United States Soviet Jews Soviet male classical composers Ukrainian classical composers Ukrainian classical pianists Ukrainian Jews United States National Medal of Arts recipients Wolf Prize in Arts laureates R. Glier Kyiv Institute of Music alumni

Vladimir Samoylovich Horowitz; yi, וולאַדימיר סאַמוילאָוויטש האָראָוויץ, group=n (November 5, 1989)Schonberg, 1992 was a

Vladimir Samoylovich Horowitz; yi, וולאַדימיר סאַמוילאָוויטש האָראָוויץ, group=n (November 5, 1989)Schonberg, 1992 was a Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

-born American classical pianist

A pianist ( , ) is an individual musician who plays the piano. Since most forms of Western music can make use of the piano, pianists have a wide repertoire and a wide variety of styles to choose from, among them traditional classical music, ja ...

. Considered one of the greatest pianists of all time, he was known for his virtuoso technique, tone color, and the public excitement engendered by his playing.

Life and early career

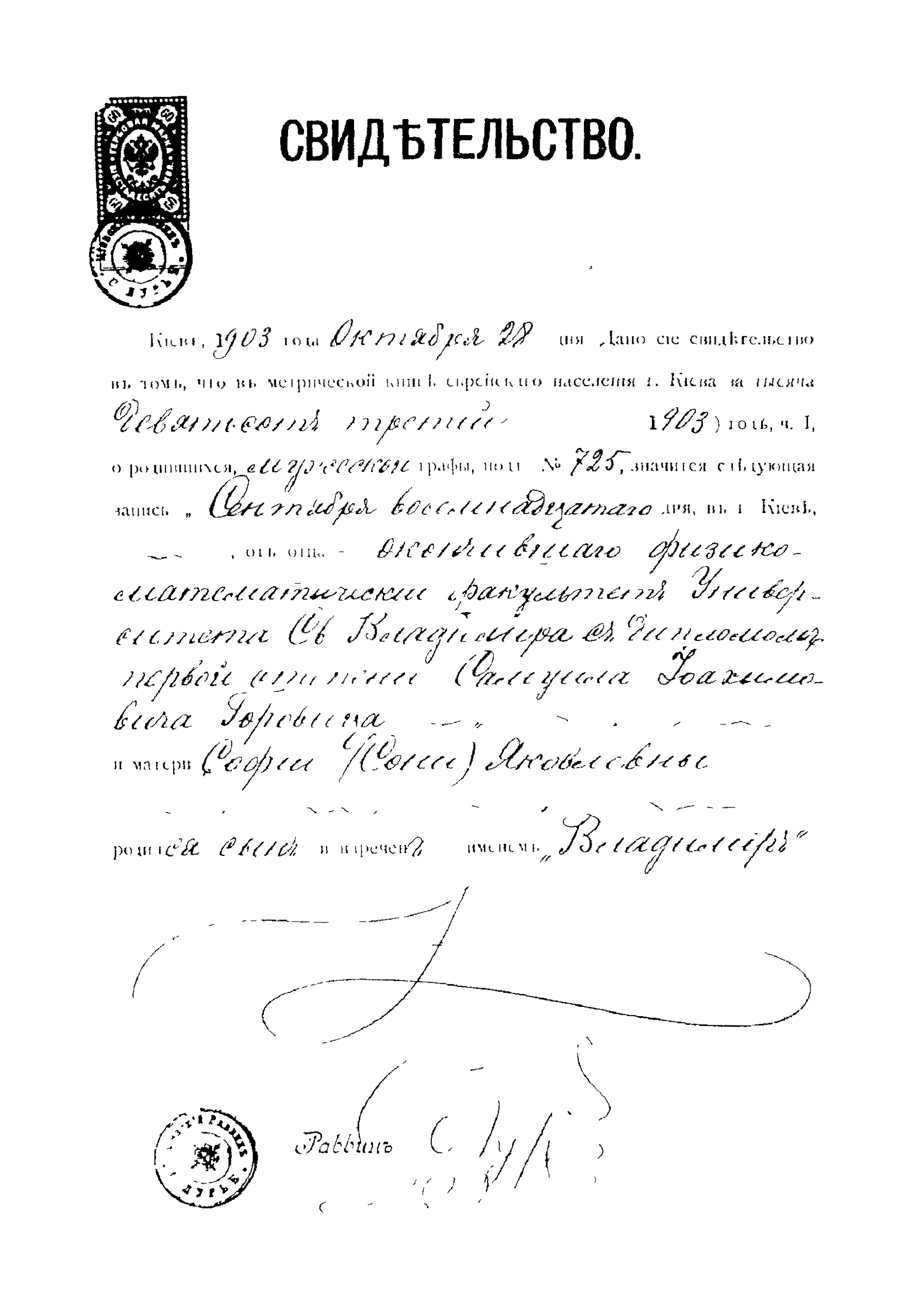

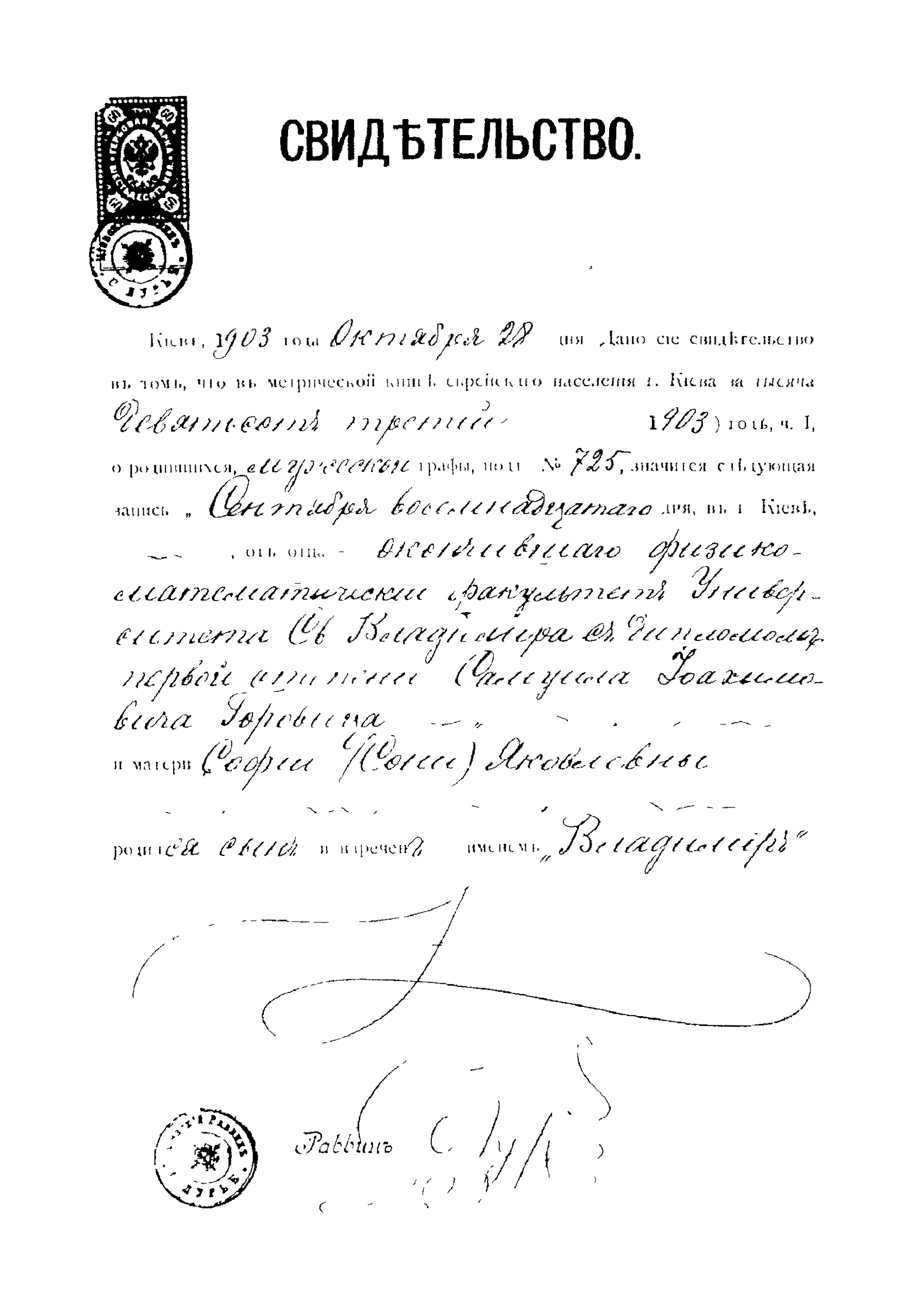

Horowitz was born on October 1, 1903, in

Horowitz was born on October 1, 1903, in Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the List of European cities by populat ...

, then in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

(now Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

). There are unsubstantiated claims that he was born in Berdichev

Berdychiv ( uk, Берди́чів, ; pl, Berdyczów; yi, באַרדיטשעװ, Barditshev; russian: Берди́чев, Berdichev) is a historic city in the Zhytomyr Oblast (province) of northern Ukraine. Serving as the administrative center ...

(a city near Zhitomir

Zhytomyr ( uk, Жито́мир, translit=Zhytomyr ; russian: Жито́мир, Zhitomir ; pl, Żytomierz ; yi, זשיטאָמיר, Zhitomir; german: Schytomyr ) is a city in the north of the western half of Ukraine. It is the administrative ...

in Volhynian Governorate

Volhynian Governorate or Volyn Governorate (russian: Волы́нская губе́рния, translit=Volynskaja gubernija, uk, Волинська губернія, translit=Volynska huberniia) was an administrative-territorial unit initially ...

), but his birth certificate unequivocally states that Kiev was his birthplace.

He was the youngest of four children of Samuil Horowitz and Sophia Bodik, who were assimilated Jews

Jewish assimilation ( he, התבוללות, ''hitbolelut'') refers either to the gradual cultural assimilation and social integration of Jews in their surrounding culture or to an ideological program in the age of emancipation promoting conform ...

. His father was a well-to-do electrical engineer and a distributor of electric motors for German manufacturers. His grandfather Joachim was a merchant (and an arts-supporter), belonging to the 1st Guild, which exempted him from having to reside in the Pale of Settlement

The Pale of Settlement (russian: Черта́ осе́длости, '; yi, דער תּחום-המושבֿ, '; he, תְּחוּם הַמּוֹשָב, ') was a western region of the Russian Empire with varying borders that existed from 1791 to 19 ...

. In order to make him appear too young for military service so as not to risk damaging his hands, Samuil took a year off his son's age by claiming that he was born in 1904. The 1904 date appeared in many reference works during Horowitz's lifetime.

His uncle Alexander was a pupil and close friend of Alexander Scriabin. When Horowitz was 10, it was arranged for him to play for Scriabin, who told his parents that he was extremely talented.

Horowitz received piano instruction from an early age, initially from his mother, who was herself a pianist. In 1912 he entered the Kiev Conservatory

Pyotr Tchaikovsky National Music Academy of Ukraine ( uk, Національна музична академія України імені Петра Чайковського) or Kyiv Conservatory is a Ukrainian state institution of higher music e ...

, where he was taught by Vladimir Puchalsky, Sergei Tarnowsky

Sergei Vladimirovich Tarnowsky (also spelled Sergei Tarnovsky; russian: Серге́й Владимирович Тарновский; 3 November 188322 March 1976) was a Russian pianist and teacher.

Biography

Tarnowsky was born in Kharkiv. Visiti ...

, and Felix Blumenfeld

Felix Mikhailovich Blumenfeld (russian: Фе́ликс Миха́йлович Блуменфе́льд; – 21 January 1931) was a Russian and Soviet composer, conductor of the Imperial Opera St-Petersburg, pianist, and teacher.

He was bor ...

. His first solo recital was in Kharkov

Kharkiv ( uk, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine.

in 1920.

Horowitz soon began to tour Russia and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, where he was often paid with bread, butter and chocolate rather than money, due to the economic hardship caused by the Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

.Plaskin, 1983, pp. 52, 56, 338–37, 353. During the 1922–23 season, he performed 23 concerts of eleven different programs in Petrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

alone. Despite his early success as a pianist, he maintained that he wanted to be a composer and undertook a career as a pianist only to help his family, who had lost their possessions in the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

.

In December 1925, Horowitz emigrated to Germany, ostensibly to study with Artur Schnabel

Artur Schnabel (17 April 1882 – 15 August 1951) was an Austrian-American classical pianist, composer and pedagogue. Schnabel was known for his intellectual seriousness as a musician, avoiding pure technical bravura. Among the 20th centur ...

in Berlin but secretly intending not to return. He stuffed American dollars and British pound notes into his shoes to finance his initial concerts.

Career in the West

On December 18, 1925, Horowitz made his first appearance outside his home country, in

On December 18, 1925, Horowitz made his first appearance outside his home country, in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

. He later played in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

, London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

, and New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. In 1926, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

selected Horowitz to join the delegation of pianists that were to represent the country at the I International Chopin Piano Competition

The I International Chopin Piano Competition ( pl, I Międzynarodowy Konkurs Pianistyczny im. Fryderyka Chopina) was the inaugural edition of the International Chopin Piano Competition, held from 23 to 30 March 1927 in Warsaw. Soviet pianist Lev ...

in Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

in 1927, but he decided to remain in the West and did not participate.

Horowitz gave his United States debut on January 12, 1928, in Carnegie Hall

Carnegie Hall ( ) is a concert venue in Midtown Manhattan in New York City. It is at 881 Seventh Avenue (Manhattan), Seventh Avenue, occupying the east side of Seventh Avenue between West 56th Street (Manhattan), 56th and 57th Street (Manhatta ...

. He played Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most popu ...

's Piano Concerto No. 1 under the direction of Sir Thomas Beecham

Sir Thomas Beecham, 2nd Baronet, CH (29 April 18798 March 1961) was an English conductor and impresario best known for his association with the London Philharmonic and the Royal Philharmonic orchestras. He was also closely associated with th ...

, who was also making his U.S. debut. Horowitz later said that he and Beecham had divergent ideas about tempos and that Beecham was conducting the score "from memory and he didn't know" the piece. Horowitz's rapport with his audience was phenomenal. Olin Downes

Edwin Olin Downes, better known as Olin Downes (January 27, 1886 – August 22, 1955), was an American music critic, known as "Sibelius's Apostle" for his championship of the music of Jean Sibelius. As critic of ''The New York Times'', he ex ...

, writing for ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', was critical about the tug of war between conductor and soloist, but credited Horowitz with both a beautiful singing tone in the second movement and a tremendous technique in the finale, calling his playing a "tornado unleashed from the steppes". In this debut performance, Horowitz demonstrated a marked ability to excite his audience, an ability he maintained for his entire career. Downes wrote: "it has been years since a pianist created such a furor with an audience in this city." In his review of Horowitz's solo recital, Downes characterized the pianist's playing as showing "most if not all the traits of a great interpreter." In 1933, he played for the first time with the conductor Arturo Toscanini

Arturo Toscanini (; ; March 25, 1867January 16, 1957) was an Italian conductor. He was one of the most acclaimed and influential musicians of the late 19th and early 20th century, renowned for his intensity, his perfectionism, his ear for orch ...

in a performance of Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 5. Horowitz and Toscanini went on to perform together many times, on stage and in recordings. Horowitz settled in the U.S. in 1939 and became an American citizen in 1944.Vladimir Horowitz on Encyclopedia.comaccessed ''15 January 2010'' He made his television debut in a concert taped at Carnegie Hall on February 1, 1968, and broadcast nationwide by CBS on September 22 of that year. Despite rapturous receptions at recitals, Horowitz became increasingly unsure of his abilities as a pianist. On several occasions, the pianist had to be pushed onto the stage. He suffered from depression and withdrew from public performances from 1936 to 1938, 1953 to 1965, 1969 to 1974, and 1983 to 1985.

Recordings

In 1926, Horowitz performed on several piano rolls at theWelte-Mignon

M. Welte & Sons, Freiburg and New York was a manufacturer of orchestrions, organs and reproducing pianos, established in Vöhrenbach by Michael Welte (1807–1880) in 1832.

Overview

From 1832 until 1932, the firm produced mechanical musi ...

studios in Freiburg

Freiburg im Breisgau (; abbreviated as Freiburg i. Br. or Freiburg i. B.; Low Alemannic: ''Friburg im Brisgau''), commonly referred to as Freiburg, is an independent city in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. With a population of about 230,000 (as o ...

, Germany. His first recordings were made in the United States for the Victor Talking Machine Company

The Victor Talking Machine Company was an American recording company and phonograph manufacturer that operated independently from 1901 until 1929, when it was acquired by the Radio Corporation of America and subsequently operated as a subsidi ...

in 1928. Horowitz's first European-produced recording, made in 1930 by The Gramophone Company/HMV, RCA Victor's UK based affiliate, was of Rachmaninoff

Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff; in Russian pre-revolutionary script. (28 March 1943) was a Russian composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor. Rachmaninoff is widely considered one of the finest pianists of his day and, as a composer, one o ...

's Piano Concerto No. 3 with Albert Coates and the London Symphony Orchestra

The London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) is a British symphony orchestra based in London. Founded in 1904, the LSO is the oldest of London's orchestras, symphony orchestras. The LSO was created by a group of players who left Henry Wood's Queen's ...

, the world premiere recording of that piece. Through 1936, Horowitz continued to make recordings in the UK for HMV of solo piano repertoire, including his 1932 account of Liszt's Sonata in B minor. Beginning in 1940, Horowitz's recording activity was again concentrated for RCA Victor in the US. That year, he recorded Brahms Piano Concerto No. 2, and in 1941, the Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1, both with the NBC Symphony Orchestra under Toscanini. In 1959, RCA Victor issued the live 1943 performance of the Tchaikovsky concerto with Horowitz and Toscanini; it is generally considered superior to the 1941 studio recording, and it was selected for the Grammy Hall of Fame

The Grammy Hall of Fame is a hall of fame to honor musical recordings of lasting qualitative or historical significance. Inductees are selected annually by a special member committee of eminent and knowledgeable professionals from all branches of ...

. During Horowitz's second retirement, which began in 1953, he made a series of recordings in his New York City townhouse

A townhouse, townhome, town house, or town home, is a type of terraced housing. A modern townhouse is often one with a small footprint on multiple floors. In a different British usage, the term originally referred to any type of city residence ...

, including LPs of Scriabin

Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin (; russian: Александр Николаевич Скрябин ; – ) was a Russian composer and virtuoso pianist. Before 1903, Scriabin was greatly influenced by the music of Frédéric Chopin and compos ...

and Clementi Clementi may refer to:

People

* Aldo Clementi (1925–2011), Italian composer

* Cecil Clementi (1875–1947), British colonial administrator and Governor of Hong Kong

* Cecilia Clementi, Italian-American scientist

* David Clementi (born 1949), B ...

. Horowitz's first stereo recording, made in 1959, was devoted to Beethoven piano sonatas.

In 1962, Horowitz embarked on a series of recordings for Columbia Records

Columbia Records is an American record label owned by Sony Music, Sony Music Entertainment, a subsidiary of Sony Corporation of America, the North American division of Japanese Conglomerate (company), conglomerate Sony. It was founded on Janua ...

. The best known are his 1965 return concert at Carnegie Hall

Carnegie Hall ( ) is a concert venue in Midtown Manhattan in New York City. It is at 881 Seventh Avenue (Manhattan), Seventh Avenue, occupying the east side of Seventh Avenue between West 56th Street (Manhattan), 56th and 57th Street (Manhatta ...

and a 1968 recording from his television special, ''Vladimir Horowitz: a Concert at Carnegie Hall'', televised by CBS

CBS Broadcasting Inc., commonly shortened to CBS, the abbreviation of its former legal name Columbia Broadcasting System, is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the CBS Entertainm ...

. Horowitz continued making studio recordings, including a 1969 recording of Schumann's ''Kreisleriana

''Kreisleriana'', Op. 16, is a composition in eight movements by Robert Schumann for solo piano, subtitled ''.'' Schumann claimed to have written it in only four days in April 1838 and a revised version appeared in 1850. The work was dedicated to ...

'', which was awarded the Prix Mondial du Disque.

In 1975, Horowitz returned to RCA and made live recordings until 1983. He signed with Deutsche Grammophon

Deutsche Grammophon (; DGG) is a German classical music record label that was the precursor of the corporation PolyGram. Headquartered in Berlin Friedrichshain, it is now part of Universal Music Group (UMG) since its merger with the UMG family of ...

in 1985, and made studio and live recordings until 1989, including his only recording of Mozart's Piano Concerto No. 23. Four documentary films featuring Horowitz were made during this period, including the telecast of his April 20, 1986 Moscow recital. His final recording, for Sony Classical

Sony Classical is an American record label founded in 1924 as Columbia Masterworks Records, a subsidiary of Columbia Records. In 1980, the Columbia Masterworks label was renamed as CBS Masterworks Records. The CBS Records Group was acquired by ...

(formerly Columbia), was completed four days before his death and consisted of repertoire he had never previously recorded.

All of Horowitz's recordings have been issued on compact disc, some several times. In the years following Horowitz's death, CDs were issued containing previously unreleased performances. These included selections from Carnegie Hall recitals recorded privately for Horowitz from 1945 to 1951.

Students

Horowitz taught seven students between 1937 and 1962: Nico Kaufmann (1937),Byron Janis

Byron Janis (born March 24, 1928) is an American classical pianist. He made several recordings for RCA Victor and Mercury Records, and occupies two volumes of the Philips series ''Great Pianists of the 20th Century''. His discography covers rep ...

(1944–1948), Gary Graffman

Gary Graffman (born October 14, 1928) is an American classical pianist, teacher and administrator.

Early life

Graffman was born in New York City to Russian-Jewish parents. Having started piano at age 3, Graffman entered the Curtis Institute of M ...

(1953–1955), Coleman Blumfield (1956–1958), Ronald Turini (1957–1963), Alexander Fiorillo (1960–1962) and Ivan Davis (1961–1962). Janis described his relationship to Horowitz during that period as a surrogate son, and he often traveled with Horowitz and his wife during concert tours. Davis was invited to become one of Horowitz's students after receiving a call from him the day after he won the Franz Liszt Competition.Plaskin, Glenn (1983) p. 305 "...he also won the Franz Liszt Competition and received a surprise phone call from Horowitz the day after the announcement. ...with 60 concerts planned for his first cross-country tour and a CBS record contract, Davis intrigued Horowitz." At the time, Davis had a contract with Columbia Records

Columbia Records is an American record label owned by Sony Music, Sony Music Entertainment, a subsidiary of Sony Corporation of America, the North American division of Japanese Conglomerate (company), conglomerate Sony. It was founded on Janua ...

and a national tour planned. Horowitz claimed that he had only taught three students during that period. "Many young people say they have been pupils of Horowitz, but there were only three: Janis, Turini, who I brought to the stage, and Graffman. If someone else claims it, it's not true. I had some who played for me for four months. Once a week. I stopped work with them because they did not progress."Plaskin, Glenn (1983) p. 300 "Many young people say they have been pupils of Horowitz, but there were only three. Janis, Turini, who I brought to the stage, and Graffman. If someone else claims it, it's not true. I had some who played for me for four months. Once a week. I stopped work with them, because they did not progress." "The fact that Horowitz disavowed most of his students and blurred the facts regarding their periods of study says something about the erratic nature of his personality during that period." According to biographer Glenn Plaskin: "The fact that Horowitz disavowed most of his students and blurred the facts regarding their periods of study says something about the erratic nature of his personality during that period". Horowitz returned to coaching in the 1980s, working with Murray Perahia, who already had an established career, and Eduardus Halim.

Personal life

In 1933, in a civil ceremony, Horowitz married

In 1933, in a civil ceremony, Horowitz married Wanda Toscanini Wanda Giorgina Toscanini Horowitz (December 7, 1907, Milan, Italy, – August 21, 1998) was the daughter of the conductor Arturo Toscanini and the wife of pianist Vladimir Horowitz.

As a child, Wanda studied piano and voice. She never pursue ...

, Arturo Toscanini

Arturo Toscanini (; ; March 25, 1867January 16, 1957) was an Italian conductor. He was one of the most acclaimed and influential musicians of the late 19th and early 20th century, renowned for his intensity, his perfectionism, his ear for orch ...

's daughter. Although Horowitz was Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

and Wanda was Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

, this was not an issue, because neither of them was religiously observant. Because Wanda knew no Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

and Horowitz knew very little Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

, their primary language was French. Horowitz was close to his wife, who was one of the few people from whom Horowitz would accept a critique of his playing, and she stayed with Horowitz when he refused to leave the house during a period of depression. They had one child, Sonia Toscanini Horowitz (1934–1975). She was critically injured in a motorbike accident in 1957 but survived. She died in 1975. It has not been determined whether her death in Geneva, from a drug overdose, was accidental or a suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and s ...

.

Despite his marriage, there were persistent rumors of Horowitz's homosexuality

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to peop ...

. Arthur Rubinstein said of Horowitz that " eryone knew and accepted him as a homosexual." David Dubal

David Dubal (born Cleveland, Ohio) is an American pianist, teacher, author, lecturer, broadcaster, and painter.

Musician and painter

Dubal has given piano recitals and master classes worldwide, and has also judged international piano competitions ...

wrote that in his years with Horowitz, there was no evidence that the octogenarian was sexually active, but that "there was no doubt he was powerfully attracted to the male body and was most likely often sexually frustrated throughout his life." Dubal felt that Horowitz sublimated a strong instinctual sexuality into a powerful erotic undercurrent communicated in his playing. Horowitz, who denied being homosexual, once joked, " ere are three kinds of pianists: Jewish pianists, homosexual pianists, and bad pianists."

In an article in ''The New York Times'' in September 2013, Kenneth Leedom, an assistant of Horowitz for five years before 1955, claimed to have secretly been Horowitz's lover: "We had a wonderful life together...He was a difficult man, to say the least. He had an anger in him that was unbelievable. The number of meals I've had thrown on the floor or in my lap. He'd pick up the tablecloth and just pull it off the table, and all the food would go flying. He had tantrums, a lot. But then he was calm and sweet. Very sweet, very lovable. And he really adored me."

In the 1940s, Horowitz began seeing a psychiatrist in an attempt to alter his sexual orientation. In the 1960s and again in the 1970s, the pianist underwent electroshock treatment

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a psychiatric treatment where a generalized seizure (without muscular convulsions) is electrically induced to manage refractory mental disorders.Rudorfer, MV, Henry, ME, Sackeim, HA (2003)"Electroconvulsive th ...

for depression.

In 1982 Horowitz began using prescribed antidepressant medications

Antidepressants are a class of medication used to treat major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, chronic pain conditions, and to help manage addictions. Common side-effects of antidepressants include dry mouth, weight gain, dizziness, hea ...

; there are reports that he was drinking alcohol as well. His playing underwent a perceptible decline during this period, with his 1983 performances in the United States and Japan marred by memory lapses and a loss of physical control. Hidekazu Yoshida

was a Japanese music critic and literary critic, active in Shōwa and Heisei Japan.

Biography

Yoshida was born in Nihonbashi, Tokyo. From an early age, he was interested in languages, and joined in club activities involving English and German ...

, Japanese critic, likened Horowitz to a "cracked rare, gorgeous antique vase." He stopped playing in public for two years.

Last years

In 1985, Horowitz, no longer taking medication or drinking alcohol, returned to performing and recording. His first post-retirement appearance was not on stage, but in the documentary film '' Vladimir Horowitz: The Last Romantic''. In many of his later performances, the octogenarian pianist substituted finesse and coloration for bravura, although he was still capable of remarkable technical feats. Many critics, including

In 1985, Horowitz, no longer taking medication or drinking alcohol, returned to performing and recording. His first post-retirement appearance was not on stage, but in the documentary film '' Vladimir Horowitz: The Last Romantic''. In many of his later performances, the octogenarian pianist substituted finesse and coloration for bravura, although he was still capable of remarkable technical feats. Many critics, including Harold C. Schonberg

Harold Charles Schonberg (29 November 1915 – 26 July 2003) was an American music critic and author. He is best known for his contributions in ''The New York Times'', where he was chief music critic from 1960 to 1980. In 1971, he became the fi ...

and Richard Dyer, felt that his post-1985 performances and recordings were the best of his later years.

In 1986, Horowitz announced that he would return to the Soviet Union for the first time since 1925 to give recitals in Moscow and Leningrad

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

. In the new atmosphere of communication and understanding between the USSR and the US, these concerts were seen as events of political, as well as musical, significance. Most of the tickets for the Moscow concert were reserved for the Soviet elite and few sold to the general public. This resulted in a number of Moscow Conservatory students crashing the concert, which was audible to viewers of the internationally televised recital. The Moscow concert was released on a compact disc titled ''Horowitz in Moscow'', which reigned at the top of Billboard's Classical music charts for over a year. It was also released on VHS and, eventually, DVD. The concert was also widely seen on a Special Edition of ''CBS News Sunday Morning

''CBS News Sunday Morning'' (normally shortened to ''Sunday Morning'' on the program itself since 2009) is an American news magazine

A news magazine is a typed, printed, and published magazine, radio or television program, usually published ...

'' with Charles Kuralt

Charles Bishop Kuralt (September 10, 1934 – July 4, 1997) was an American television, newspaper and radio journalist and author. He is most widely known for his long career with CBS, first for his "On the Road" segments on '' The CBS Eveni ...

reporting from Moscow.

Following the Russian concerts, Horowitz toured several European cities, including Berlin, Amsterdam, and London. In June, Horowitz redeemed himself to the Japanese with a trio of well-received performances in Tokyo. Later that year he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, along with the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by the president of the United States to recognize people who have made "an especially merito ...

, the highest civilian honor bestowed by the United States, by President Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

.

Horowitz's final tour took place in Europe in the spring of 1987. A video recording of his penultimate public recital, ''Horowitz in Vienna'', was released in 1991. His final recital, at the Musikhalle Hamburg, Germany, took place on June 21, 1987. The concert was recorded, but not released until 2008. He continued to record for the remainder of his life.

Death

Vladimir Horowitz died on November 5, 1989, in New York City of aheart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which may tr ...

, aged 86. He was buried in the Toscanini family tomb in the Cimitero Monumentale, Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

, Italy.

Repertoire, technique and performance style

Horowitz is best known for his performances of the Romantic piano repertoire. Many consider Horowitz's first recording of the Liszt Sonata in B minor in 1932 to be the definitive reading of that piece, even after over 80 years and more than 100 performances committed to disc by other pianists. Other pieces with which he was closely associated were Scriabin's Étude in D-sharp minor, Chopin's Ballade No. 1, and many Rachmaninoff miniatures, including ''

Horowitz is best known for his performances of the Romantic piano repertoire. Many consider Horowitz's first recording of the Liszt Sonata in B minor in 1932 to be the definitive reading of that piece, even after over 80 years and more than 100 performances committed to disc by other pianists. Other pieces with which he was closely associated were Scriabin's Étude in D-sharp minor, Chopin's Ballade No. 1, and many Rachmaninoff miniatures, including ''Polka de W.R.

Sergei Rachmaninoff's ''Polka de W.R.'' is a virtuoso piano arrangement of Franz Behr's '' Lachtäubchen'' (Scherzpolka) in F major.

Composition

Rachmaninoff wrote the arrangement on 24 March 1911, the day after the premiere of the '' Litur ...

''. Horowitz was acclaimed for his recordings of the Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 3, and his performance before Rachmaninoff awed the composer, who proclaimed "he swallowed it whole. He had the courage, the intensity, the daring." Horowitz was also known for his performances of quieter, more intimate works, including Schumann's ''Kinderszenen

' (, "Scenes from Childhood"), Op. 15, by Robert Schumann, is a set of thirteen pieces of music for piano written in 1838.

History and description

Schumann wrote 30 movements for this work but chose 13 for the final version. The unused mo ...

'', Scarlatti's keyboard sonatas, keyboard sonatas by Clementi Clementi may refer to:

People

* Aldo Clementi (1925–2011), Italian composer

* Cecil Clementi (1875–1947), British colonial administrator and Governor of Hong Kong

* Cecilia Clementi, Italian-American scientist

* David Clementi (born 1949), B ...

and several Mozart and Haydn sonatas. His recordings of Scarlatti and Clementi are particularly prized, and he is credited with having helped revive interest in the two composers, whose works had been seldom performed or recorded during the first half of the 20th century.

During World War II, Horowitz championed contemporary Russian music, giving the American premieres of Prokofiev's Piano Sonatas Nos. 6, 7 and 8 (the so-called "War Sonatas") and Kabalevsky

Dmitry Borisovich Kabalevsky (russian: Дми́трий Бори́сович Кабале́вский ; 14 February 1987) was a Soviet composer, conductor, pianist and pedagogue of Russian gentry descent.

He helped set up the Union of Soviet C ...

's Piano Sonatas Nos. 2 and 3. Horowitz also premiered the Piano Sonata

A piano sonata is a sonata written for a solo piano. Piano sonatas are usually written in three or four movements, although some piano sonatas have been written with a single movement ( Scarlatti, Liszt, Scriabin, Medtner, Berg), others with ...

and ''Excursions'' of Samuel Barber

Samuel Osmond Barber II (March 9, 1910 – January 23, 1981) was an American composer, pianist, conductor, baritone, and music educator, and one of the most celebrated composers of the 20th century. The music critic Donal Henahan said, "Proba ...

.

He was known for his versions of several of Liszt's ''Hungarian Rhapsodies

The Hungarian Rhapsodies, S.244, R.106 (french: Rhapsodies hongroises, german: Ungarische Rhapsodien, hu, Magyar rapszódiák), is a set of 19 piano pieces based on Hungarian folk themes, composed by Franz Liszt during 1846–1853, and late ...

''. The ''Second Rhapsody'' was recorded in 1953, during Horowitz's 25th anniversary concert at Carnegie Hall, and he said it was the most difficult of his arrangements. Horowitz's transcriptions of note include his composition '' Variations on a Theme from Carmen'' and ''The Stars and Stripes Forever

"The Stars and Stripes Forever" is a patriotic American march written and composed by John Philip Sousa in 1896. By a 1987 act of the U.S. Congress, it is the official National March of the United States of America.

History

In his 1928 autob ...

'' by John Philip Sousa

John Philip Sousa ( ; November 6, 1854 – March 6, 1932) was an American composer and conductor of the late Romantic era known primarily for American military marches. He is known as "The March King" or the "American March King", to dis ...

. The latter became a favorite with audiences, who would anticipate its performance as an encore. Transcriptions aside, Horowitz was not opposed to altering the text of compositions to improve what he considered "unpianistic" writing or structural clumsiness. In 1940, with the composer's consent, Horowitz created his own performance edition of Rachmaninoff's

Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff; in Russian pre-revolutionary script. (28 March 1943) was a Russian composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor. Rachmaninoff is widely considered one of the finest pianists of his day and, as a composer, one o ...

Second Piano Sonata from the 1913 original and 1931 revised versions, which pianists including Ruth Laredo

Ruth Laredo (November 20, 1937May 25, 2005) was an American Classical music, classical pianist.

She became known in the 1970s in particular for her premiere recordings of the 10 sonatas of Alexander Scriabin, Scriabin and the complete solo piano ...

and Hélène Grimaud

Hélène Rose Paule Grimaud (born 7 November 1969) is a French classical pianist and the founder of the Wolf Conservation Center in South Salem, New York.

Early life and education

Grimaud was born in Aix-en-Provence, France. She described fami ...

have used. He substantially rewrote Mussorgsky

Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky ( rus, link=no, Модест Петрович Мусоргский, Modest Petrovich Musorgsky , mɐˈdɛst pʲɪˈtrovʲɪtɕ ˈmusərkskʲɪj, Ru-Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky version.ogg; – ) was a Russian compo ...

's ''Pictures at an Exhibition

''Pictures at an Exhibition'', french: Tableaux d'une exposition, link=no is a suite of ten piano pieces, plus a recurring, varied Promenade theme, composed by Russian composer Modest Mussorgsky in 1874. The piece is Mussorgsky's most famous pia ...

'' to make the work more effective on the grounds that Mussorgsky was not a pianist and did not understand the possibilities of the instrument. Horowitz also altered short passages in some works, such as substituting interlocking octaves for chromatic scales in Chopin's Scherzo in B minor. This was in marked contrast to many pianists of the post–19th-century era, who considered the composer's text sacrosanct. Living composers whose works Horowitz played (among them Rachmaninoff

Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff; in Russian pre-revolutionary script. (28 March 1943) was a Russian composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor. Rachmaninoff is widely considered one of the finest pianists of his day and, as a composer, one o ...

, Prokofiev

Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev; alternative transliterations of his name include ''Sergey'' or ''Serge'', and ''Prokofief'', ''Prokofieff'', or ''Prokofyev''., group=n (27 April .S. 15 April1891 – 5 March 1953) was a Russian composer, p ...

, and Poulenc) invariably praised Horowitz's performances of their work even when he took liberties with their scores.

Horowitz's interpretations were well received by concert audiences, but not by some critics. Virgil Thomson

Virgil Thomson (November 25, 1896 – September 30, 1989) was an American composer and critic. He was instrumental in the development of the "American Sound" in classical music. He has been described as a modernist, a neoromantic, a neoclass ...

was consistently critical of Horowitz as a "master of distortion and exaggeration" in his reviews appearing in the '' New York Herald Tribune''. Horowitz claimed to take Thomson's remarks as complimentary, saying that Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (; 6 March 1475 – 18 February 1564), known as Michelangelo (), was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was insp ...

and El Greco were also "masters of distortion." In the 1980 edition of ''Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians

''The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'' is an encyclopedic dictionary of music and musicians. Along with the German-language ''Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart'', it is one of the largest reference works on the history and theo ...

'', Michael Steinberg wrote that Horowitz "illustrates that an astounding instrumental gift carries no guarantee about musical understanding." ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' music critic Harold C. Schonberg

Harold Charles Schonberg (29 November 1915 – 26 July 2003) was an American music critic and author. He is best known for his contributions in ''The New York Times'', where he was chief music critic from 1960 to 1980. In 1971, he became the fi ...

countered that reviewers such as Thomson and Steinberg were unfamiliar with 19th-century performance practices that informed Horowitz's musical approach. Many pianists (such as Martha Argerich

Martha Argerich (; Eastern Catalan: �ɾʒəˈɾik born 5 June 1941) is an Argentine classical concert pianist. She is widely considered to be one of the greatest pianists of all time.

Early life and education

Argerich was born in Buenos A ...

and Maurizio Pollini

Maurizio Pollini (born 5 January 1942) is an Italian pianist. He is known for performances of compositions by Beethoven, Chopin and Debussy, among others. He has also championed and performed works by contemporary composers such as Pierre Boulez ...

) hold Horowitz in high regard, and the pianist Friedrich Gulda

Friedrich Gulda (16 May 1930 – 27 January 2000) was an Austrian pianist and composer who worked in both the classical and jazz fields.

Biography Early life and career

Born in Vienna the son of a teacher, Gulda began learning to play the piano ...

referred to Horowitz as the "over-God of the piano".

Horowitz's style frequently involved vast dynamic contrasts, with overwhelming double-fortissimos followed by sudden delicate pianissimos. He was able to produce an extraordinary volume of sound from the piano without producing a harsh tone. He elicited an exceptionally wide range of tonal color, and his taut, precise attack was noticeable even in his renditions of technically undemanding pieces such as the Chopin Mazurkas

The mazurka ( Polish: ''mazur'' Polish ball dance, one of the five Polish national dances and ''mazurek'' Polish folk dance') is a Polish musical form based on stylised folk dances in triple meter, usually at a lively tempo, with character ...

. He is known for his octave

In music, an octave ( la, octavus: eighth) or perfect octave (sometimes called the diapason) is the interval between one musical pitch and another with double its frequency. The octave relationship is a natural phenomenon that has been refer ...

technique; he could play precise passages in octaves extraordinarily quickly. When asked by the pianist Tedd Joselson how he practiced octaves, Horowitz gave a demonstration and Joselson reported, "He practiced them exactly as we were all taught to do." Music critic and biographer Harvey Sachs submitted that Horowitz may have been "the beneficiary—and perhaps also the victim—of an extraordinary central nervous system and an equally great sensitivity to tone color." Oscar Levant

Oscar Levant (December 27, 1906August 14, 1972) was an American concert pianist, composer, conductor, author, radio game show panelist, television talk show host, comedian and actor. He was awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for rec ...

, in his book ''The Memoirs of an Amnesiac'', wrote that Horowitz's octaves were "brilliant, accurate and etched out like bullets." He asked Horowitz "whether he shipped them ahead or carried them with him on tour."

Horowitz's hand position was unusual in that the palm was often below the level of the key surface. He frequently played chords with straight fingers, and the little finger of his right hand was often curled up until it needed to play a note; to Harold C. Schonberg, "it was like a strike of a cobra." For all the excitement of his playing, Horowitz rarely raised his hands higher than the piano's fallboard. Byron Janis

Byron Janis (born March 24, 1928) is an American classical pianist. He made several recordings for RCA Victor and Mercury Records, and occupies two volumes of the Philips series ''Great Pianists of the 20th Century''. His discography covers rep ...

, one of Horowitz's students, said that Horowitz tried to teach him that technique but it didn't work for him. Horowitz's body was immobile, and his face seldom reflected anything other than intense concentration.

Horowitz preferred to perform on Sunday afternoons, as he felt audiences were better rested and more attentive than on weekday evenings.

Awards and recognitions

Grammy Award for Best Classical Performance – Instrumental Soloist or Soloists (with or without orchestra) * 1968 ''Horowitz in Concert: Haydn,Schumann

Robert Schumann (; 8 June 181029 July 1856) was a German composer, pianist, and influential music critic. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers of the Romantic era. Schumann left the study of law, intending to pursue a career a ...

, Scriabin

Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin (; russian: Александр Николаевич Скрябин ; – ) was a Russian composer and virtuoso pianist. Before 1903, Scriabin was greatly influenced by the music of Frédéric Chopin and compos ...

, Debussy

(Achille) Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influential composers of the ...

, Mozart, Chopin'' (Columbia 45572)

* 1969 ''Horowitz on Television: Chopin, Scriabin, Scarlatti, Horowitz'' (Columbia 7106)

* 1987 ''Horowitz: The Studio Recordings, New York 1985'' (Deutsche Grammophon 419217)

Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Soloist(s) Performance (with orchestra) The Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Soloist(s) Performance (with orchestra) was awarded from 1959 to 2011. From 1967 to 1971, and in 1987, the award was combined with the award for Best Instrumental Soloist Performance (without orchestra) and aw ...

* 1979 ''Golden Jubilee Concert'', ''Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto No. 3'' (RCA CLR1 2633)

* 1989 ''Horowitz Plays Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 23 ''(Deutsche Grammophon 423287)

Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Soloist Performance (without orchestra)

The Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Soloist Performance (without orchestra) was awarded from 1959 to 2011. From 1967 to 1971, and in 1987, the award was combined with the award for Best Instrumental Soloist(s) Performance (with orchestra) and aw ...

* 1963 ''Columbia Records Presents Vladimir Horowitz''

* 1964 ''The Sound of Horowitz''

* 1965 ''Vladimir Horowitz plays Beethoven, Debussy, Chopin''

* 1966 ''Horowitz at Carnegie Hall – An Historic Return''

* 1972 ''Horowitz Plays Rachmaninoff (Etudes-Tableaux Piano Music; Sonatas)'' (Columbia M-30464)

* 1973 ''Horowitz Plays Chopin'' (Columbia M-30643)

* 1974 ''Horowitz Plays Scriabin

Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin (; russian: Александр Николаевич Скрябин ; – ) was a Russian composer and virtuoso pianist. Before 1903, Scriabin was greatly influenced by the music of Frédéric Chopin and compos ...

'' (Columbia M-31620)

* 1977 ''The Horowitz Concerts 1975/76'' (RCA ARL1-1766)

* 1979 ''The Horowitz Concerts 1977/78'' (RCA ARL1-2548)

* 1980 ''The Horowitz Concerts 1978/79'' (RCA ARL1-3433)

* 1982 ''The Horowitz Concerts 1979/80'' (RCA ARL1-3775)

* 1988 ''Horowitz in Moscow'' (Deutsche Grammophon 419499)

* 1991 ''The Last Recording'' (Sony SK 45818)

* 1993 ''Horowitz Discovered Treasures: Chopin, Liszt, Scarlatti, Scriabin, Clementi'' (Sony 48093)

Grammy Award for Best Classical Album

The Grammy Award for Best Classical Album was awarded from 1962 to 2011. The award had several minor name changes:

*From 1962 to 1963, 1965 to 1972 and 1974 to 1976 the award was known as Album of the Year – Classical

*In 1964 and 1977 it wa ...

:

* 1963 ''Columbia Records Presents Vladimir Horowitz''

* 1966 ''Horowitz at Carnegie Hall: An Historic Return''

* 1972 ''Horowitz Plays Rachmaninoff (Etudes-Tableaux Piano Music; Sonatas)''

* 1978 ''Concert of the Century'' with Leonard Bernstein

Leonard Bernstein ( ; August 25, 1918 – October 14, 1990) was an American conductor, composer, pianist, music educator, author, and humanitarian. Considered to be one of the most important conductors of his time, he was the first America ...

(conductor), the New York Philharmonic

The New York Philharmonic, officially the Philharmonic-Symphony Society of New York, Inc., globally known as New York Philharmonic Orchestra (NYPO) or New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra, is a symphony orchestra based in New York City. It is ...

, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (28 May 1925 – 18 May 2012) was a German lyric baritone and conductor of classical music, one of the most famous Lieder (art song) performers of the post-war period, best known as a singer of Franz Schubert's Lieder, ...

, Vladimir Horowitz, Yehudi Menuhin

Yehudi or Jehudi (Hebrew: יהודי, endonym for Jew) is a common Hebrew name:

* Yehudi Menuhin (1916–1999), violinist and conductor

** Yehudi Menuhin School, a music school in Surrey, England

** Who's Yehoodi?, a catchphrase referring to t ...

, Mstislav Rostropovich, Isaac Stern

Isaac Stern (July 21, 1920 – September 22, 2001) was an American violinist.

Born in Poland, Stern came to the US when he was 14 months old. Stern performed both nationally and internationally, notably touring the Soviet Union and China, and ...

, Lyndon Woodside

* 1987 ''Horowitz: The Studio Recordings, New York 1985'' (Deutsche Grammophon 419217)

* 1988 ''Horowitz in Moscow'' (Deutsche Grammophon 419499)

Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, 1990

Prix Mondial du Disque

* 1970 ''Kreisleriana

''Kreisleriana'', Op. 16, is a composition in eight movements by Robert Schumann for solo piano, subtitled ''.'' Schumann claimed to have written it in only four days in April 1838 and a revised version appeared in 1850. The work was dedicated to ...

''

Miscellaneous awards

* 1972 – Honorary Member of the Royal Academy of Music (London)

* 1982 – Wolf Foundation Prize for Music

* 1985 – Commandeur de la Légion d'honneur from the French Government

* 1985 – Order of Merit of the Italian Republic

The Order of Merit of the Italian Republic ( it, Ordine al Merito della Repubblica Italiana) is the senior Italian order of merit. It was established in 1951 by the second President of the Italian Republic, Luigi Einaudi.

The highest-ranking ...

* 1986 – United States Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, along with the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by the president of the United States to recognize people who have made "an especially merito ...

* 1988 – National Bow Tie

The bow tie is a type of necktie. A modern bow tie is tied using a common shoelace knot, which is also called the bow knot for that reason. It consists of a ribbon of fabric tied around the collar of a shirt in a symmetrical manner so that t ...

League List of 10 Best Bow Tie Wearers of 1988

* 2012 – '' Gramophone'' Hall of Fame entrant

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * Epstein, Helen. Music Talks (1988) McGraw-Hill (a long profile that appeared in the New York Times Magazine of Horowitz, 1978) * Plaskin, Glenn (1983)''Horowitz: A Biography of Vladimir Horowitz.''

UK: Macdonald. *

External links

The Horowitz Papers

at the Irving S. Gilmore Music Library, Yale University

Vladimir Horowitz website at Sony Classical

Vladimir Horowitz at Deutsche Grammophon

Vladimir Horowitz at Encyclopædia Britannica

* *

Entry at 45worlds.com

{{DEFAULTSORT:Horowitz, Vladimir 1903 births 1989 deaths 20th-century American composers 20th-century American male musicians 20th-century classical composers 20th-century classical pianists 20th-century LGBT people 20th-century Russian male musicians 20th-century Ukrainian musicians American classical composers American classical pianists American male classical composers American male classical pianists American people of Russian-Jewish descent American people of Ukrainian-Jewish descent Burials at the Cimitero Monumentale di Milano Deutsche Grammophon artists American gay musicians Grammy Award winners Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners Grand Crosses with Star and Sash of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany Honorary Members of the Royal Academy of Music Jewish American classical composers Jewish American classical musicians Jewish classical pianists Jewish Ukrainian musicians LGBT classical composers LGBT classical musicians LGBT Jews LGBT musicians from Russia LGBT people from Ukraine Music & Arts artists Musicians from Kyiv People from Kiev Governorate Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients Recipients of the Legion of Honour Recipients of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic Royal Philharmonic Society Gold Medallists Russian classical composers Russian classical pianists Russian Jews Russian male classical composers Soviet classical composers Soviet classical pianists Soviet emigrants to the United States Soviet Jews Soviet male classical composers Ukrainian classical composers Ukrainian classical pianists Ukrainian Jews United States National Medal of Arts recipients Wolf Prize in Arts laureates R. Glier Kyiv Institute of Music alumni