Vel' d'Hiv Roundup on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Vel' d'Hiv' Roundup ( ; from french: Rafle du Vel' d'Hiv', an abbreviation of ) was a

mass arrest

A mass arrest occurs when police apprehend large numbers of suspects at once. This sometimes occurs at protests. Some mass arrests are also used in an effort to combat gang activity. This is sometimes controversial, and lawsuits sometimes result. I ...

of foreign Jewish families by French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

police and gendarmes

Wrong info! -->

A gendarmerie () is a military force with law enforcement duties among the civilian population. The term ''gendarme'' () is derived from the medieval French expression ', which translates to "men-at-arms" (literally, " ...

at the behest of the German authorities, that took place in Paris on 16 and 17 July 1942. According to records of the'' Préfecture de Police'', 13,152 Jews were arrested, including more than 4,000 children.

They were held at the Vélodrome d'Hiver ( 'Winter Stadium'; known as "Vel’ d’Hiv") in extremely crowded conditions, almost without food and water and with no sanitary facilities. In the week following the arrests, the Jews were taken to the Drancy

Drancy () is a commune in the northeastern suburbs of Paris in the Seine-Saint-Denis department in northern France. It is located 10.8 km (6.7 mi) from the center of Paris.

History

Toponymy

The name Drancy comes from Medieval La ...

, Pithiviers

Pithiviers () is a commune in the Loiret department, north central France. It is one of the subprefectures of Loiret. It is twinned with Ashby-de-la-Zouch in Leicestershire, England and Burglengenfeld in Bavaria, Germany.

Its attractions incl ...

, and Beaune-la-Rolande internment camp

Beaune-la-Rolande internment camp was an internment and transit camp for foreign-born Jews (men, women, and children), located in Beaune-la-Rolande in occupied France, it was operational between May 1941 and July 1943, during World War II.

Th ...

s, before being shipped in rail cattle cars to Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 Nazi concentration camps, concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, occupied Poland (in a portion annexed int ...

for their mass murder

Mass murder is the act of murdering a number of people, typically simultaneously or over a relatively short period of time and in close geographic proximity. The United States Congress defines mass killings as the killings of three or more pe ...

.

The roundup was one of several aimed at eradicating the Jewish population in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, both in the occupied zone and in the free zone. French President Jacques Chirac

Jacques René Chirac (, , ; 29 November 193226 September 2019) was a Politics of France, French politician who served as President of France from 1995 to 2007. Chirac was previously Prime Minister of France from 1974 to 1976 and from 1986 to ...

apologized in 1995 for the complicit role that French police and civil servants played in the raid. In 2017, President Emmanuel Macron

Emmanuel Macron (; born 21 December 1977) is a French politician who has served as President of France since 2017. ''Ex officio'', he is also one of the two Co-Princes of Andorra. Prior to his presidency, Macron served as Minister of Econ ...

more specifically admitted the responsibility of the French State in the roundup and, hence, in the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

.

The Vélodrome d'Hiver

The Vélodrome d'Hiver was a large indoor sports arena at the corner of the and in the15th arrondissement of Paris

15 (fifteen) is the natural number following 14 and preceding 16.

Mathematics

15 is:

* A composite number, and the sixth semiprime; its proper divisors being , and .

* A deficient number, a smooth number, a lucky number, a pernicious nu ...

, not far from the Eiffel Tower

The Eiffel Tower ( ; french: links=yes, tour Eiffel ) is a wrought-iron lattice tower on the Champ de Mars in Paris, France. It is named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built the tower.

Locally nicknamed ...

. It was built by Henri Desgrange

Henri Desgrange (31 January 1865 – 16 August 1940) was a French bicycle racer and sports journalist. He set twelve world track cycling records, including the hour record of on 11 May 1893. He was the first organiser of the Tour de France.

...

, editor of L'Auto, who later organised the Tour de France

The Tour de France () is an annual men's multiple-stage bicycle race primarily held in France, while also occasionally passing through nearby countries. Like the other Grand Tours (the Giro d'Italia and the Vuelta a España), it consists ...

, as a velodrome

A velodrome is an arena for track cycling. Modern velodromes feature steeply banked oval tracks, consisting of two 180-degree circular bends connected by two straights. The straights transition to the circular turn through a moderate easement ...

(cycle track

A cycle track, separated bike lane or protected bike lane (sometimes historically referred to as a sidepath) is an exclusive bikeway that has elements of a separated path and on-road bike lane. A cycle track is located within or next to the r ...

) when his original track in the nearby ''Salle des Machines'' was listed for demolition in 1909 to improve the view of the Eiffel Tower. As well as track cycling, the new building was used for ice hockey

Ice hockey (or simply hockey) is a team sport played on ice skates, usually on an ice skating rink with lines and markings specific to the sport. It belongs to a family of sports called hockey. In ice hockey, two opposing teams use ice ...

, wrestling

Wrestling is a series of combat sports involving grappling-type techniques such as clinch fighting, throws and takedowns, joint locks, pins and other grappling holds. Wrestling techniques have been incorporated into martial arts, combat s ...

, boxing

Boxing (also known as "Western boxing" or "pugilism") is a combat sport in which two people, usually wearing protective gloves and other protective equipment such as hand wraps and mouthguards, throw punches at each other for a predetermined ...

, roller-skating, circus

A circus is a company of performers who put on diverse entertainment shows that may include clowns, acrobats, trained animals, trapeze acts, musicians, dancers, hoopers, tightrope walkers, jugglers, magicians, ventriloquists, and unicyclis ...

es, spectacles and demonstrations. In the 1924 Summer Olympics

The 1924 Summer Olympics (french: Jeux olympiques d'été de 1924), officially the Games of the VIII Olympiad (french: Jeux de la VIIIe olympiade) and also known as Paris 1924, were an international multi-sport event held in Paris, France. The o ...

, several events were held there, including foil fencing, boxing, cycling (track), weightlifting, and wrestling.

The Vel d'Hiv was also the site of political rallies and demonstrations, including a large event attended by Xavier Vallat, Philippe Henriot, Leon Daudet and other notable antisemites when Charles Maurras

Charles-Marie-Photius Maurras (; ; 20 April 1868 – 16 November 1952) was a French author, politician, poet, and critic. He was an organizer and principal philosopher of ''Action Française'', a political movement that is monarchist, anti-parl ...

was released from prison. In 1939 Jewish refugees were interned there before being sent to camps in the Paris region and in 1940 it was used as a internment center for foreign women, an event that served as a precedent for its selection as internment location.

Precursors

The "Vel' d'Hiv' Roundup" was not the first roundup of this sort in France during World War II. In what is known as thegreen ticket roundup

The green ticket roundup (french: rafle du billet vert), also known as the green card roundup, took place on 14 May 1941 during the Nazi occupation of France. The mass arrest started a day after French Police delivered a green card () to 6694 f ...

(french: rafle du billet vert), 3,747 Jewish men were arrested on 14 May 1941, after 6,694 foreign Jews living in France received a summons in the mail (delivered on a green ticket) to a status review (french: examen de situation). The summons was a trap: those who honoured their summons were arrested and taken by bus the same day to the Gare d'Austerlitz

The Gare d'Austerlitz (English: Austerlitz Station), officially Paris-Austerlitz, is one of the six large Paris rail termini. The station is located on the left bank of the Seine in the southeastern part of the city, in the 13th arrondisseme ...

, then shipped in four special trains to two camps at Pithiviers

Pithiviers () is a commune in the Loiret department, north central France. It is one of the subprefectures of Loiret. It is twinned with Ashby-de-la-Zouch in Leicestershire, England and Burglengenfeld in Bavaria, Germany.

Its attractions incl ...

and Beaune-La-Rolande in the Loiret

Loiret (; ) is a department in the Centre-Val de Loire region of north-central France. It takes its name from the river Loiret, which is contained wholly within the department. In 2019, Loiret had a population of 680,434.< ...

department. Women, children, and more men followed in July 1942.

Planning the roundup

The Vel' d'Hiv' Roundup, was part of the "Final Solution

The Final Solution (german: die Endlösung, ) or the Final Solution to the Jewish Question (german: Endlösung der Judenfrage, ) was a Nazi plan for the genocide of individuals they defined as Jews during World War II. The "Final Solution to th ...

", a continent-wide plan to intern and exterminate Europe's Jewish population, it was a joint operation between German and collaborating French administrators.

The first anti-Jewish ordinance of 27 September 1940, promulgated by the German authorities, forced Jewish people in the Occupied Zone, including foreigners, to register at police stations or at sous-préfectures ("sub-prefectures"). Nearly 150,000 people registered in the department of the Seine that encompasses Paris and its immediate suburbs. Their names and addresses were kept by the French police in the fichier Tulard, a file named after its creator, André Tulard. Theodor Dannecker

Theodor Denecke (also spelled Dannecker) (27 March 1913 – 10 December 1945) was a German SS-captain (), a key aide to Adolf Eichmann in the deportation of Jews during World War II.

A trained lawyer Denecke first served at the Reich Security ...

, the SS captain who headed the German police in France, said: "This filing system subdivided into files sorted alphabetically; Jews with French nationality and foreign Jews had files of different colors, and the files were also sorted, according to profession, nationality and street." These files were then given to the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one orga ...

, in charge of the "Jewish problem." At the request of the German authorities, the Vichy government created in March 1941 the Commissariat Général aux Questions Juives or CGQJ (Commissariat-General for Jewish Affairs) with the task of implementing antisemitic policy.

On 4 July 1942 René Bousquet

René Bousquet (; 11 May 1909 – 8 June 1993) was a high-ranking French political appointee who served as secretary general to the Vichy French police from May 1942 to 31 December 1943. For personal heroism, he had become a protégé of promine ...

, secretary-general of the national police, and Louis Darquier de Pellepoix, who had replaced Xavier Vallat in May 1942 as head of the CGQJ, travelled to Gestapo headquarters at 93 rue Lauriston in the 16th arrondissement of Paris to meet Dannecker and Helmut Knochen

Helmut Herbert Christian Heinrich Knochen (March 14, 1910 – April 4, 2003) was the senior commander of the Sicherheitspolizei (Security Police) and Sicherheitsdienst in Paris during the Nazi occupation of France during World War II. He was s ...

of the SS. The previous roundups had come short of the 32,000 jews promised by the French authorities to the Germans. Darquier proposed the arrest of stateless Jews in the Southern Zone and the denaturalization of all Jews who acquired French citizenship from 1927. A further meeting took place in Dannecker's office on the avenue Foch on 7 July. Also present were Jean Leguay, Bousquet's deputy, Jean François, who was director of the police administration at the Paris prefecture, Émile Hennequin, head of Paris police, and André Tulard.

Dannecker met Adolf Eichmann

Otto Adolf Eichmann ( ,"Eichmann"

'' Heinz Röthke, Ernst Heinrichsohn, Jean Leguay, Gallien, deputy to Darquier de Pellepoix, several police officials and representatives of the French railway service, the

The position of the French police was complicated by the sovereignty of the Vichy government, which nominally administered France while accepting occupation of the north. Although in practice the Germans ran the north and had a strong and later total domination in the south, the formal position was that France and the Germans were separate. The position of Vichy and its leader,

The position of the French police was complicated by the sovereignty of the Vichy government, which nominally administered France while accepting occupation of the north. Although in practice the Germans ran the north and had a strong and later total domination in the south, the formal position was that France and the Germans were separate. The position of Vichy and its leader,

The internment camp at Drancy was easily defended because it was built of tower blocks in the shape of a horseshoe. It was guarded by French gendarmes. The camp's operation was under the Gestapo's section of Jewish affairs. Theodor Dannecker, a key figure both in the roundup and in the operation of Drancy, was described by Maurice Rajsfus in his history of the camp as "a violent psychopath.... It was he who ordered the internees to starve, who banned them from moving about within the camp, to smoke, to play cards, etc."

In December 1941, forty prisoners from Drancy were murdered in retaliation for a French attack on German police officers.

Immediate control of the camp was under Heinz Röthke. It was under his direction from August 1942 to June 1943 that almost two thirds of those deported in

The internment camp at Drancy was easily defended because it was built of tower blocks in the shape of a horseshoe. It was guarded by French gendarmes. The camp's operation was under the Gestapo's section of Jewish affairs. Theodor Dannecker, a key figure both in the roundup and in the operation of Drancy, was described by Maurice Rajsfus in his history of the camp as "a violent psychopath.... It was he who ordered the internees to starve, who banned them from moving about within the camp, to smoke, to play cards, etc."

In December 1941, forty prisoners from Drancy were murdered in retaliation for a French attack on German police officers.

Immediate control of the camp was under Heinz Röthke. It was under his direction from August 1942 to June 1943 that almost two thirds of those deported in

René Bousquet was last to be tried, in 1949. He was acquitted of "compromising the interests of the national defence", but declared guilty of for involvement in the Vichy government. He was given five years of ''

René Bousquet was last to be tried, in 1949. He was acquitted of "compromising the interests of the national defence", but declared guilty of for involvement in the Vichy government. He was given five years of ''

After the Liberation, survivors of the internment camp at Drancy began legal proceedings against gendarmes accused of being accomplices of the Nazis. An investigation began into 15 gendarmes, of whom 10 were accused at the Cour de justice of the

After the Liberation, survivors of the internment camp at Drancy began legal proceedings against gendarmes accused of being accomplices of the Nazis. An investigation began into 15 gendarmes, of whom 10 were accused at the Cour de justice of the

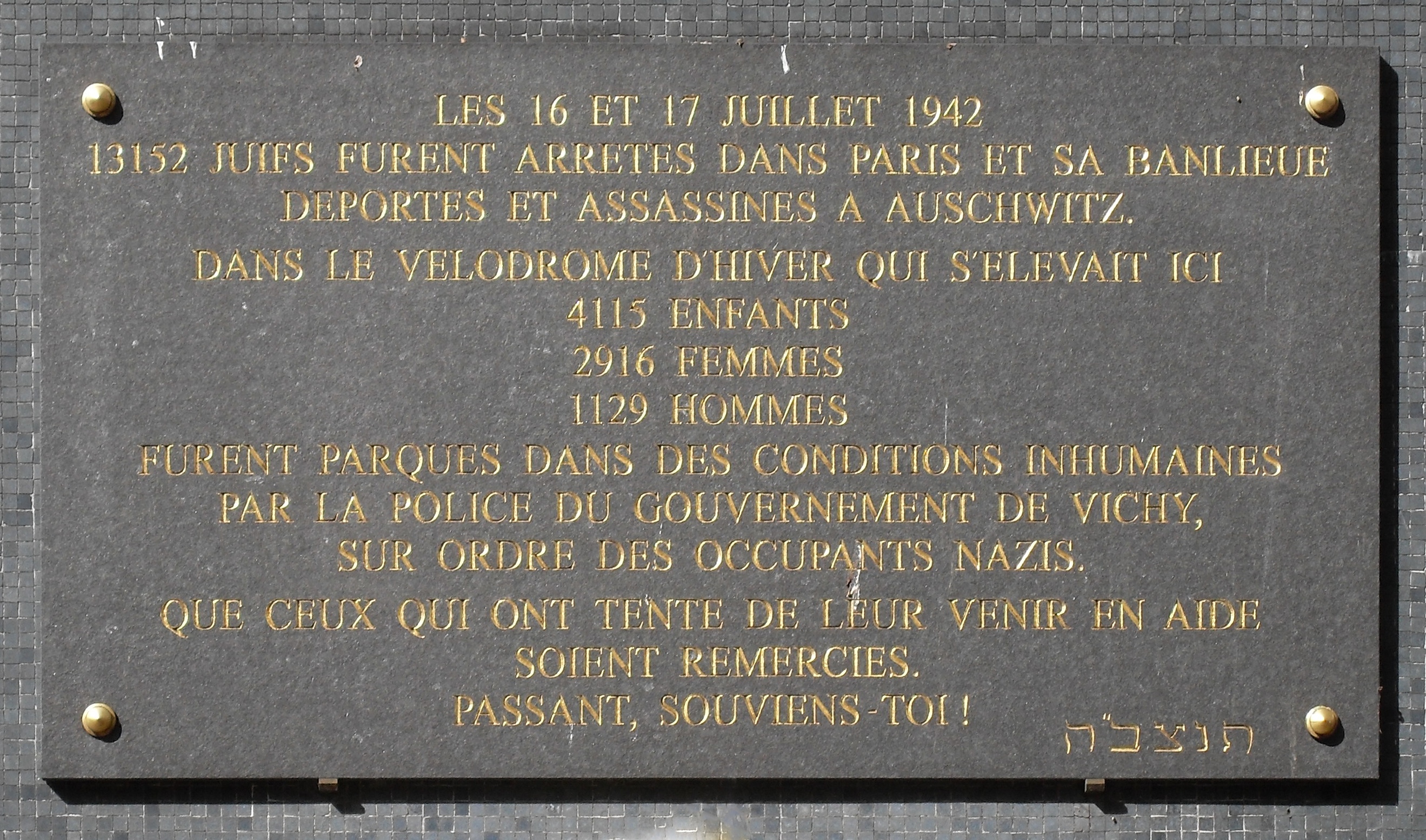

A fire destroyed part of the ''Vélodrome d'Hiver'' in 1959 and the rest of the structure was demolished. A block of flats and a building belonging to the Ministry of the Interior now stand on the site. A plaque marking the Vel' d'Hiv' Roundup was placed on the track building after the War and moved to 8 boulevard de Grenelle in 1959.

On 3 February 1993, President François Mitterrand commissioned a monument to be erected on the site. It stands now on a curved base, to represent the cycle track, on the edge of the quai de Grenelle. It is the work of the Polish sculptor Walter Spitzer and the architect Mario Azagury. Spitzer's family were survivors of deportation to Auschwitz. The statue represents all deportees but especially those of the Vel' d'Hiv'. The sculptures include children, a pregnant woman and a sick man. The words on the Mitterrand-era monument still differentiate between the French Republic and the Vichy Government that ruled during WW II, so they do not accept State responsibility for the roundup of the Jews. The words are in French: "", which translate as follows: "The French Republic pays homage to the victims of racist and anti-Semitic persecutions and crimes against humanity committed under the de facto authority called the 'Government of the French State' 1940–1944. Let us never forget." The monument was inaugurated on 17 July 1994. A commemorative ceremony is held here every year in July.

A memorial plaque in memory of victims of the Vel' d'Hiv' raid was placed at the Bir-Hakeim station of the

A fire destroyed part of the ''Vélodrome d'Hiver'' in 1959 and the rest of the structure was demolished. A block of flats and a building belonging to the Ministry of the Interior now stand on the site. A plaque marking the Vel' d'Hiv' Roundup was placed on the track building after the War and moved to 8 boulevard de Grenelle in 1959.

On 3 February 1993, President François Mitterrand commissioned a monument to be erected on the site. It stands now on a curved base, to represent the cycle track, on the edge of the quai de Grenelle. It is the work of the Polish sculptor Walter Spitzer and the architect Mario Azagury. Spitzer's family were survivors of deportation to Auschwitz. The statue represents all deportees but especially those of the Vel' d'Hiv'. The sculptures include children, a pregnant woman and a sick man. The words on the Mitterrand-era monument still differentiate between the French Republic and the Vichy Government that ruled during WW II, so they do not accept State responsibility for the roundup of the Jews. The words are in French: "", which translate as follows: "The French Republic pays homage to the victims of racist and anti-Semitic persecutions and crimes against humanity committed under the de facto authority called the 'Government of the French State' 1940–1944. Let us never forget." The monument was inaugurated on 17 July 1994. A commemorative ceremony is held here every year in July.

A memorial plaque in memory of victims of the Vel' d'Hiv' raid was placed at the Bir-Hakeim station of the

''ICH BIN''

with the support from the Fondation Hippocrène and from the EACEA Agency of the European Commission (Programme Europe for citizens – An active European remembrance), RTBF, VRT. * William Karel, 1992. ''La Rafle du Vel-d'Hiv'', La Marche du siècle,

Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence: ''Case Study: The Vélodrome d'Hiver Round-up: July 16 and 17, 1942''

Le monument commémoratif du quai de Grenelle à Paris

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20061012122235/http://new.filter.ac.uk/database/getinsight.php?id=51 Occupied France: Commemorating the Deportation

additional photographs

French government booklet

2012 speech of President François Hollande

The Vel' d'Hiv Roundup

at the online exhibition The Holocaust in France at

The trains of the Holocaust

by Hedi Enghelberg, digital book edition, www.amazon.com, The ENG Publishing, 2010-2012 {{DEFAULTSORT:Vel Dhiv Roundup The Holocaust in France War crimes in France Vichy France 1942 in France Reparations July 1942 events 1942 in Judaism

'' Heinz Röthke, Ernst Heinrichsohn, Jean Leguay, Gallien, deputy to Darquier de Pellepoix, several police officials and representatives of the French railway service, the

SNCF

The Société nationale des chemins de fer français (; abbreviated as SNCF ; French for "National society of French railroads") is France's national state-owned railway company. Founded in 1938, it operates the country's national rail traffic ...

. The roundup was delayed until after Bastille Day

Bastille Day is the common name given in English-speaking countries to the national day of France, which is celebrated on 14 July each year. In French, it is formally called the (; "French National Celebration"); legally it is known as (; "t ...

on 14 July at the request of the French. This national holiday was not celebrated in the occupied zone, and they wished to avoid civil uprisings. Dannecker declared: "The French police, despite a few considerations of pure form, have only to carry out orders!"CDJC

The Center for Contemporary Jewish Documentation is an independent French organization

founded by Isaac Schneersohn in 1943 in the town of Grenoble, France during the Second World War to preserve the evidence of Nazi war crimes for future gener ...

-CCCLXIV 2. Document produced in court Oberg- Knochen in September 1954, cited by Maurice Rajsfus in ''La Police de Vichy – Les forces de l'ordre au service de la Gestapo, 1940/1944'', Le Cherche Midi, 1995, p. 118

The roundup was aimed at Jews from Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

, Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

and the ''apatrides'' ("stateless"), whose origin couldn't be determined, aged from 16 to 50. There were to be exceptions for women "in advanced state of pregnancy" or who were breast-feeding, but "to save time, the sorting will be made not at home but at the first assembly centre".

The Germans planned for the French police to arrest 22,000 Jews in Greater Paris. They would then be taken to internment camps at Drancy

Drancy () is a commune in the northeastern suburbs of Paris in the Seine-Saint-Denis department in northern France. It is located 10.8 km (6.7 mi) from the center of Paris.

History

Toponymy

The name Drancy comes from Medieval La ...

, Compiègne

Compiègne (; pcd, Compiène) is a commune in the Oise department in northern France. It is located on the river Oise. Its inhabitants are called ''Compiégnois''.

Administration

Compiègne is the seat of two cantons:

* Compiègne-1 (with ...

, Pithiviers

Pithiviers () is a commune in the Loiret department, north central France. It is one of the subprefectures of Loiret. It is twinned with Ashby-de-la-Zouch in Leicestershire, England and Burglengenfeld in Bavaria, Germany.

Its attractions incl ...

and Beaune-la-Rolande. André Tulard "will obtain from the head of the municipal police the files of Jews to be arrested. Children of less than 15 or 16 years will be sent to the '' Union générale des israélites de France'' (UGIF, General Union of French Jews), which will place them in foundations. The sorting of children will be done in the first assembly centres."

Police complicity

The position of the French police was complicated by the sovereignty of the Vichy government, which nominally administered France while accepting occupation of the north. Although in practice the Germans ran the north and had a strong and later total domination in the south, the formal position was that France and the Germans were separate. The position of Vichy and its leader,

The position of the French police was complicated by the sovereignty of the Vichy government, which nominally administered France while accepting occupation of the north. Although in practice the Germans ran the north and had a strong and later total domination in the south, the formal position was that France and the Germans were separate. The position of Vichy and its leader, Philippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Pétain (24 April 1856 – 23 July 1951), commonly known as Philippe Pétain (, ) or Marshal Pétain (french: Maréchal Pétain), was a French general who attained the position of Marshal of France at the end of Worl ...

, was recognised throughout the war by many foreign governments.

This independence, however fictional, had to be preserved. German interference in internal policing, says the historian Julian T. Jackson, "would further erode that sovereignty which Vichy was so committed to preserving. This could only be avoided by reassuring Germany that the French would carry out the necessary measures." Jackson adds that the decision to arrest Jews and Communists and Gaullists was "an autonomous policy, with its own indigenous roots." In other words, the decision to do so was not forced upon the Vichy regime by the Germans. Jackson also explains that the roundup of Jews must have been run by the French, since the Germans would not have had the necessary information or manpower to find and arrest a full 13,000 people.

On 2 July 1942, René Bousquet attended a planning meeting in which he raised no objection to the arrests, and worried only about the ("embarrassing") fact that the French police would carry them out. Bousquet succeeded in reaching a compromise -- that the police would round up only foreign Jews. Vichy ratified that agreement the following day.

Although the police have been blamed for rounding up children younger than 16—the age was set to preserve a fiction that workers were needed in the east—the order was given by Pétain's minister, Pierre Laval

Pierre Jean Marie Laval (; 28 June 1883 – 15 October 1945) was a French politician. During the Third Republic, he served as Prime Minister of France from 27 January 1931 to 20 February 1932 and 7 June 1935 to 24 January 1936. He again occ ...

, supposedly as a "humanitarian" measure to keep families together. This too was a fiction, given that the parents of these children had already been deported; documents of the period have revealed that the anti-Semitic Laval's principal concern was what to do with Jewish children once their parents had been deported. The youngest child sent to Auschwitz under Laval's orders was 18 months old.

Three former SS officers testified in 1980 that Vichy officials had been enthusiastic about deportation of Jews from France. Investigator Serge Klarsfeld found minutes in German archives of meetings with senior Vichy officials and Bousquet's proposal that the roundup should cover non-French Jews throughout the country. In 1990, charges of crimes against humanity were laid against Bousquet in relation to his role in the Vel' d'Hiv' roundup of Jews, based on complaints filed by Klarsfield.

The historians Antony Beevor

Sir Antony James Beevor, (born 14 December 1946) is a British military historian. He has published several popular historical works on the Second World War and the Spanish Civil War.

Early life

Born in Kensington, Beevor was educated at tw ...

and Artemis Cooper

Artemis Cooper, Lady Beevor FRSL (born Alice Clare Antonia Opportune Cooper; 22 April 1953) is a British writer, primarily of biographies. She is married to historian Sir Antony Beevor.

Family life

She is the only daughter of The 2nd Viscoun ...

record:

Klarsfeld also revealed the telegrams Bousquet had sent to Prefects of ''départements'' in the occupied zone, ordering them to deport not only Jewish adults but children whose deportation had not even been requested by the Nazis.

Roundup

Émile Hennequin, director of the city police, ordered on 12 July 1942 that "the operations must be effected with the maximum speed, without pointless speaking and without comment." Beginning at 4:00 a.m. on 16 July 1942, French police numbering 9,000 started the manhunt. The Police force included gendarmes, gardes mobiles, detectives, patrolmen and cadets; they were divided into small arresting teams of three or four men each, fanning across the city. A few hundred followers ofJacques Doriot

Jacques Doriot (; 26 September 1898 – 22 February 1945) was a French politician, initially communist, later fascist, before and during World War II.

In 1936, after his exclusion from the Communist Party, he founded the French Popular Party (P ...

volunteered to help, wearing armband with the colours of the fascist French Popular Party

The French Popular Party (french: Parti populaire français) was a French fascist and anti-semitic political party led by Jacques Doriot before and during World War II. It is generally regarded as the most collaborationist party of France.

...

(PPF).

In total 13,152 Jews were arrested. According to records of the Paris Préfecture de police, 5,802 (44%) of these were women and 4,051 (31%) were children. An unknown number of people managed to escape, warned by a clandestine Jewish newspaper or the French Resistance

The French Resistance (french: La Résistance) was a collection of organisations that fought the German occupation of France during World War II, Nazi occupation of France and the Collaborationism, collaborationist Vichy France, Vichy régim ...

, hidden by neighbors or benefiting from the lack of zeal or thoroughness of some policemen. Conditions for the arrested were harsh: they could take only a blanket, a sweater, a pair of shoes and two shirts with them. Most families were split up and never reunited.

Some of those captured were taken by bus to an internment camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simp ...

in an unfinished complex of apartments and apartment towers in the northern suburb of Drancy, the rest were taken to the Vélodrome d'Hiver which had already been used as an internment center in the summer of 1941.

The Vel' d'Hiv'

The Vel' d'Hiv' was available for hire to whoever wanted it. Among those who had booked it wasJacques Doriot

Jacques Doriot (; 26 September 1898 – 22 February 1945) was a French politician, initially communist, later fascist, before and during World War II.

In 1936, after his exclusion from the Communist Party, he founded the French Popular Party (P ...

, who led France's largest fascist

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

party, the ''Parti Populaire Français

The French Popular Party (french: Parti populaire français) was a French fascist and anti-semitic political party led by Jacques Doriot before and during World War II. It is generally regarded as the most collaborationist party of France.

...

'' (PPF). It was at the Vel' d'Hiv' among other venues that Doriot, with his Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

-like salute, roused crowds to join his cause. Among those who helped in the ''Rafle du Vel' d'hiv were 3,400 young members of Doriot's PPF.

The Germans demanded the keys of the Vel' d'Hiv' from its owner, Jacques Goddet, who had taken over from his father Victor and Henri Desgrange. The circumstances in which Goddet surrendered the keys remain a mystery and the episode is given only a few lines in his autobiography.

The Vel' d'Hiv' had a glass roof, which had been painted dark blue to avoid attracting bomber navigators. The dark glass increased the heat, as well as windows screwed shut for security. The numbers held there vary from one account to another, but one established figure is 7,500 of a final figure of 13,152.''Le Figaro'', 22 July 2002 There were no lavatories: of the 10 available, five were sealed because their windows offered a way out, and the others were blocked. The arrested Jews were kept there with only food and water brought by Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abili ...

. The Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

and a few doctors and nurses were allowed to enter. There was only one water faucet. Those who tried to escape were shot on the spot. Some took their own lives.

After five days, the prisoners were taken to the internment camps of Drancy, Beaune-la-Rolande and Pithiviers, and later to the extermination camps

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (german: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocaust. The v ...

.

After the roundup

Roundups were conducted in both the northern and southern zones of France, but public outrage was greatest in Paris because of the numbers involved in a concentrated area. The Vel' d'Hiv' was a landmark in the city centre. TheRoman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

church was among the protesters. Public reaction obliged Laval to ask the Germans on 2 September not to demand more Jews. Handing them over, he said, was not like buying items in a discount store. Laval managed to limit deportations mainly to foreign Jews; he and his defenders argued after the war that allowing the French police to conduct the roundup had been a bargain to ensure the life of Jews of French nationality.

In reality, "Vichy shed no tears over the fate of the foreign Jews in France, who were seen as a nuisance, '' ("garbage") in Laval's words. Laval told an American diplomat that he was "happy" to get rid of them.

When a Protestant leader accused Laval of murdering Jews, Laval insisted they had been sent to build an agricultural colony in the East. "I talked to him about murder, he answered me with gardening."

Drancy camp and deportation

The internment camp at Drancy was easily defended because it was built of tower blocks in the shape of a horseshoe. It was guarded by French gendarmes. The camp's operation was under the Gestapo's section of Jewish affairs. Theodor Dannecker, a key figure both in the roundup and in the operation of Drancy, was described by Maurice Rajsfus in his history of the camp as "a violent psychopath.... It was he who ordered the internees to starve, who banned them from moving about within the camp, to smoke, to play cards, etc."

In December 1941, forty prisoners from Drancy were murdered in retaliation for a French attack on German police officers.

Immediate control of the camp was under Heinz Röthke. It was under his direction from August 1942 to June 1943 that almost two thirds of those deported in

The internment camp at Drancy was easily defended because it was built of tower blocks in the shape of a horseshoe. It was guarded by French gendarmes. The camp's operation was under the Gestapo's section of Jewish affairs. Theodor Dannecker, a key figure both in the roundup and in the operation of Drancy, was described by Maurice Rajsfus in his history of the camp as "a violent psychopath.... It was he who ordered the internees to starve, who banned them from moving about within the camp, to smoke, to play cards, etc."

In December 1941, forty prisoners from Drancy were murdered in retaliation for a French attack on German police officers.

Immediate control of the camp was under Heinz Röthke. It was under his direction from August 1942 to June 1943 that almost two thirds of those deported in SNCF

The Société nationale des chemins de fer français (; abbreviated as SNCF ; French for "National society of French railroads") is France's national state-owned railway company. Founded in 1938, it operates the country's national rail traffic ...

box car transports requisitioned by the Nazis from Drancy were sent to Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 Nazi concentration camps, concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, occupied Poland (in a portion annexed int ...

. Drancy is also where Klaus Barbie sent Jewish children captured in a raid of a children's home before shipping them to Auschwitz, where they were murdered. Most of the initial victims, including those from the Vel' d'Hiv', were crammed into sealed wagons and died from lack of food and water. Those who survived the passage were murdered in the gas chambers.

At the Liberation of Paris

The liberation of Paris (french: Libération de Paris) was a military battle that took place during World War II from 19 August 1944 until the German garrison surrendered the French capital on 25 August 1944. Paris had been occupied by Nazi Ger ...

in August 1944, the camp was run by the Resistance—"to the frustration of the authorities; the Prefect of Police had no control at all and visitors were not welcome"—who used it to house not Jews, but those it considered collaborators with the Germans. When a pastor was allowed in on 15 September, he discovered cells 3.5m by 1.75m that held six Jewish internees with two mattresses between them. The prison returned to the conventional prison service on 20 September.

Aftermath

The roundup accounted for more than a quarter of the Jews sent from France to Auschwitz in 1942, of whom only 811 returned to France at the end of the war. With the exception of six adolescents, none of the 3,900 children detained at the Vel d’Hiv and then deported survived. Pierre Laval's trial opened on 3 October 1945. His first defence was that he had been obliged to sacrifice foreign Jews to save the French. Uproar broke out in the court, with supposedly neutral jurors shouting abuse at Laval, threatening "a dozen bullets in his hide". It was, said historiansAntony Beevor

Sir Antony James Beevor, (born 14 December 1946) is a British military historian. He has published several popular historical works on the Second World War and the Spanish Civil War.

Early life

Born in Kensington, Beevor was educated at tw ...

and Artemis Cooper

Artemis Cooper, Lady Beevor FRSL (born Alice Clare Antonia Opportune Cooper; 22 April 1953) is a British writer, primarily of biographies. She is married to historian Sir Antony Beevor.

Family life

She is the only daughter of The 2nd Viscoun ...

, "a cross between an and a tribunal during the Paris Terror". From 6 October, Laval refused to take part in the proceedings, hoping that the jurors' interventions would lead to a new trial. Laval was sentenced to death, and tried to commit suicide by swallowing a cyanide capsule. Revived by doctors, he was executed by a firing squad at Fresnes Prison on 15 October.

Jean Leguay survived the war and its aftermath and became president of Warner Lambert, Inc. in London (now merged with Pfizer), and later president of Substantia Laboratories in Paris. In 1979, he was charged for his role in the roundup.

Louis Darquier was sentenced to death in 1947 for collaboration. However, he had fled to Spain, where the Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War and thereafter ruled over Spain from 193 ...

regime protected him. In 1978, after he gave an interview claiming that the gas chambers of Auschwitz were used to kill lice, the French government requested his extradition. Spain refused. He died on 29 August 1980, near Málaga

Málaga (, ) is a municipality of Spain, capital of the Province of Málaga, in the autonomous community of Andalusia. With a population of 578,460 in 2020, it is the second-most populous city in Andalusia after Seville and the sixth most po ...

, Spain.

Helmut Knochen

Helmut Herbert Christian Heinrich Knochen (March 14, 1910 – April 4, 2003) was the senior commander of the Sicherheitspolizei (Security Police) and Sicherheitsdienst in Paris during the Nazi occupation of France during World War II. He was s ...

was sentenced to death by a British military tribunal in 1946 for the murder of British pilots. The sentence was never carried out. He was extradited to France in 1954 and again sentenced to death. The sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment. In 1962, French president Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Governm ...

pardoned him and he was sent back to Germany, where he retired in Baden-Baden

Baden-Baden () is a spa town in the state of Baden-Württemberg, south-western Germany, at the north-western border of the Black Forest mountain range on the small river Oos, ten kilometres (six miles) east of the Rhine, the border with Fra ...

and died in 2003.

Émile Hennequin, head of Paris police, was sentenced to eight years' penal labour in June 1947.

René Bousquet was last to be tried, in 1949. He was acquitted of "compromising the interests of the national defence", but declared guilty of for involvement in the Vichy government. He was given five years of ''

René Bousquet was last to be tried, in 1949. He was acquitted of "compromising the interests of the national defence", but declared guilty of for involvement in the Vichy government. He was given five years of ''dégradation nationale

The ''dégradation nationale'' ("National demotion") was a sentence introduced in France after the Liberation of France. It was applied during the ''épuration légale'' ("legal purge") which followed the fall of the Vichy regime.

The ''dégra ...

'', a measure immediately lifted for "having actively and sustainably participated in the resistance against the occupier". Bousquet's position was always ambiguous; there were times he worked with the Germans and others when he worked against them. After the war he worked at the Banque d'Indochine and in newspapers. In 1957, the '' Conseil d'État'' gave back his ''Légion d'honneur'', and he was given an amnesty on 17 January 1958. He stood for election that year as a candidate for the Marne. He was supported by the Democratic and Socialist Union of the Resistance; his second was Hector Bouilly, a radical-socialist general councillor. In 1974, Bousquet helped finance François Mitterrand

François Marie Adrien Maurice Mitterrand (26 October 19168 January 1996) was President of France, serving under that position from 1981 to 1995, the longest time in office in the history of France. As First Secretary of the Socialist Party, he ...

's presidential campaign against Valéry Giscard d'Estaing

Valéry René Marie Georges Giscard d'Estaing (, , ; 2 February 19262 December 2020), also known as Giscard or VGE, was a French politician who served as President of France from 1974 to 1981.

After serving as Minister of Finance under prime ...

. In 1986, as accusations cast on Bousquet grew more credible, particularly after he was named by Louis Darquier, he and Mitterrand stopped seeing each other. The parquet général de Paris closed the case by sending it to a court that no longer existed. Lawyers for the International Federation of Human Rights

The International Federation for Human Rights (french: Fédération internationale des ligues des droits de l'homme; FIDH) is a non-governmental federation for human rights organizations. Founded in 1922, FIDH is the third oldest international h ...

spoke of a "political decision at the highest levels to prevent the Bousquet affair from developing". In 1989, Serge Klarsfeld and his , the and the filed a complaint against Bousquet for crimes against humanity

Crimes against humanity are widespread or systemic acts committed by or on behalf of a ''de facto'' authority, usually a state, that grossly violate human rights. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity do not have to take place within the ...

for the deportation of 194 children. Bousquet was committed to trial but on 8 June 1993 a 55-year-old mental patient named Christian Didier entered his flat and shot him dead.

Theodor Dannecker was interned by the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

in December 1945 and a few days later committed suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and ...

.

Jacques Doriot, whose French right-wing followers helped in the round-up, fled to the Sigmaringen enclave in Germany and became a member of the exile Vichy government there. He died in February 1945 when his car was strafed by Allied fighters while he was travelling from Mainau

Mainau also referred to as Mav(e)no(w), Maienowe (in 1242), Maienow (in 1357), Maienau, Mainowe (in 1394) and Mainaw (in 1580) is an island in Lake Constance (on the Southern shore of the Überlinger See near the city of Konstanz, Baden- ...

to Sigmaringen. He was buried in Mengen.

Action against the police

After the Liberation, survivors of the internment camp at Drancy began legal proceedings against gendarmes accused of being accomplices of the Nazis. An investigation began into 15 gendarmes, of whom 10 were accused at the Cour de justice of the

After the Liberation, survivors of the internment camp at Drancy began legal proceedings against gendarmes accused of being accomplices of the Nazis. An investigation began into 15 gendarmes, of whom 10 were accused at the Cour de justice of the Seine

)

, mouth_location = Le Havre/ Honfleur

, mouth_coordinates =

, mouth_elevation =

, progression =

, river_system = Seine basin

, basin_size =

, tributaries_left = Yonne, Loing, Eure, Risle

, tributa ...

of conduct threatening the safety of the state. Three fled before the trial began. The other seven said they were only obeying orders, despite numerous witnesses and accounts by survivors of their brutality.

The court ruled on 22 March 1947 that the seven were guilty but that most had rehabilitated themselves "by active participation, useful and sustained, offered to the Resistance against the enemy." Two others were jailed for two years and condemned to ''dégradation nationale

The ''dégradation nationale'' ("National demotion") was a sentence introduced in France after the Liberation of France. It was applied during the ''épuration légale'' ("legal purge") which followed the fall of the Vichy regime.

The ''dégra ...

'' for five years. A year later they were reprieved.

Government admission

For decades the French government declined to apologize for the role of French policemen in the roundup or for state complicity. De Gaulle and others argued that theFrench Republic

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

had been dismantled when Philippe Pétain instituted a new French State during the war and that the Republic had been re-established when the war was over. It was not for the Republic, therefore, to apologise for events caused by a state which France did not recognise. President François Mitterrand

François Marie Adrien Maurice Mitterrand (26 October 19168 January 1996) was President of France, serving under that position from 1981 to 1995, the longest time in office in the history of France. As First Secretary of the Socialist Party, he ...

reiterated this position in a September 1994 speech. "I will not apologize in the name of France. The Republic had nothing to do with this. I do not believe France is responsible."

On 16 July 1995, the next President, Jacques Chirac

Jacques René Chirac (, , ; 29 November 193226 September 2019) was a Politics of France, French politician who served as President of France from 1995 to 2007. Chirac was previously Prime Minister of France from 1974 to 1976 and from 1986 to ...

, reversed that position, stating that it was time that France faced up to its past. He acknowledged the role that "the French State" played in the persecution of Jews and others during the War.

Il est difficile de les évoquer, aussi, parce que ces heures noires souillent à jamais notre histoire, et sont une injure à notre passé et à nos traditions. Oui, la folie criminelle de l'occupant a été secondée par des Français, par l'Etat français. Il y a cinquante-trois ans, le 16 juillet 1942, 450 policiers et gendarmes français, sous l'autorité de leurs chefs, répondaient aux exigences des nazis. Ce jour-là, dans la capitale et en région parisienne, près de dix mille hommes, femmes et enfants juifs furent arrêtés à leur domicile, au petit matin, et rassemblés dans les commissariats de police.... La France, patrie des Lumières et des Droits de l'Homme, terre d'accueil et d'asile, la France, ce jour-là, accomplissait l'irréparable. Manquant à sa parole, elle livrait ses protégés à leurs bourreaux. ("These black hours will stain our history forever and are an injury to our past and our traditions. Yes, the criminal madness of the occupier was assisted by the French, by the French state. Fifty-three years ago, on 16 July 1942, 450 French policemen and gendarmes, under the authority of their leaders, obeyed the demands of the Nazis. That day, in the capital and the Paris region, nearly 10,000 Jewish men, women and children were arrested at home, in the early hours of the morning, and assembled at police stations... France, home of the Enlightenment and the Rights of Man, land of welcome and asylum, France committed on that day the irreparable. Breaking its word, it delivered those it protected to their executioners.")To mark the 70th anniversary of the Vél d'Hiv' roundup, President

François Hollande

François Gérard Georges Nicolas Hollande (; born 12 August 1954) is a French politician who served as President of France from 2012 to 2017. He previously was First Secretary of the Socialist Party (France), First Secretary of the Socialist P ...

gave a speech at the monument on 22 July 2012. The president recognized that this event was a crime committed "in France, by France," and emphasized that the deportations in which French police participated were offences committed against French values, principles, and ideals.

The earlier claim that the Government of France during World War II was some illegitimate group was again advanced by Marine Le Pen

Marion Anne Perrine "Marine" Le Pen (; born 5 August 1968) is a French lawyer and politician who ran for the French presidency in 2012, 2017, and 2022. A member of the National Rally (RN; previously the National Front, FN), she served as its ...

, leader of the National Front Party, during the 2017 election campaign. In speeches, she claimed that the Vichy government was "not France".

On 16 July 2017, also in commemoration of the victims of the roundup, President Emmanuel Macron

Emmanuel Macron (; born 21 December 1977) is a French politician who has served as President of France since 2017. ''Ex officio'', he is also one of the two Co-Princes of Andorra. Prior to his presidency, Macron served as Minister of Econ ...

denounced his country's role in the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europ ...

and the historical revisionism that denied France's responsibility for 1942 roundup and subsequent deportation of 13,000 Jews. "It was indeed France that organised this oundup, he said, French police collaborating with the Nazis. "Not a single German took part," he added. Chirac had already stated that the Government during the War represented the French State. Macron was even more specific in this respect: "It is convenient to see the Vichy regime as born of nothingness, returned to nothingness. Yes, it's convenient, but it is false. We cannot build pride upon a lie."

Macron made a subtle reference to Chirac's 1995 apology when he added, "I say it again here. It was indeed France that organized the roundup, the deportation, and thus, for almost all, death."

Memorials and monuments

Paris

Paris Métro

The Paris Métro (french: Métro de Paris ; short for Métropolitain ) is a rapid transit system in the Paris metropolitan area, France. A symbol of the city, it is known for its density within the capital's territorial limits, uniform architec ...

on 20 July 2008. The ceremony was led by Jean-Marie Bockel, Secretary of Defense and Veterans Affairs, and was attended by Simone Veil

Simone Veil (; ; 13 July 1927 – 30 June 2017) was a French magistrate and politician who served as Health Minister in several governments and was President of the European Parliament from 1979 to 1982, the first woman to hold that office. ...

, a deportee and former minister, anti-Nazi activist Beate Klarsfeld, and numerous dignitaries.

Drancy

A memorial was also constructed in 1976 at Drancy internment camp, after a design competition won byShelomo Selinger

Shelomo Selinger (born May 31, 1928) is a sculptor and artist living and working in Paris since 1956.

Biography

Selinger was born to a Jewish family in the small Polish town of Szczakowa (today part of Jaworzno) near Oświęcim (Auschwitz''Le P ...

. It stands beside a rail wagon of the sort used to take prisoners to the death camps. It is three blocks forming the Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

letter Shin, traditionally written on the Mezuzah

A ''mezuzah'' ( he, מְזוּזָה "doorpost"; plural: ''mezuzot'') is a piece of parchment, known as a '' klaf'', contained in a decorative case and inscribed with specific Hebrew verses from the Torah ( and ). These verses consist of the ...

at the door of houses occupied by Jews. Two other blocks represent the gates of death. Shelomo Selinger said of his work: "The central block is composed of 10 figures, the number needed for collective prayer (Minyan

In Judaism, a ''minyan'' ( he, מניין \ מִנְיָן ''mīnyān'' , lit. (noun) ''count, number''; pl. ''mīnyānīm'' ) is the quorum of ten Jewish adults required for certain religious obligations. In more traditional streams of Ju ...

). The two Hebrew letters Lamed and Vav are formed by the hair, the arm and the beard of two people at the top of the sculpture. These letters have the numeric 36, the number of Righteous thanks to whom the world exists according to Jewish tradition."

On 25 May 2001, the cité de la Muette—formal name of the Drancy apartment blocks—was declared a national monument by the culture minister, Catherine Tasca

Catherine Tasca (born 13 December 1941 in Lyon) was a member of the Senate of France, representing the Yvelines department from 2004 to 2017. She is a member of the Socialist Party, and served as the Senate's vice-president. From 2000 to 2002 s ...

.

A new Shoah memorial museum was opened in 2012 just opposite the sculpture memorial and railway wagon by President François Hollande. It provides details of the persecution of the Jews in France and many personal mementos of inmates before their deportation to Auschwitz and their death. They include messages written on the walls, graffiti

Graffiti (plural; singular ''graffiti'' or ''graffito'', the latter rarely used except in archeology) is art that is written, painted or drawn on a wall or other surface, usually without permission and within public view. Graffiti ranges from s ...

, drinking mugs and other personal belongings left by the prisoners, some of which are inscribed with the names of the owners. The ground floor also shows a changing exhibit of prisoner faces and names, as a memorial to their imprisonment and then murder by the Germans, assisted by the French gendarmerie

Wrong info! -->

A gendarmerie () is a military force with law enforcement duties among the civilian population. The term ''gendarme'' () is derived from the medieval French expression ', which translates to " men-at-arms" (literally, ...

.

The Holocaust researcher Serge Klarsfeld said in 2004: "Drancy is the best known place for everyone of the memory of the Shoah in France; in the crypt of Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem ( he, יָד וַשֵׁם; literally, "a memorial and a name") is Israel's official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust. It is dedicated to preserving the memory of the Jews who were murdered; honoring Jews who fought against th ...

( Jérusalem), where stones are engraved with the names of the most notorious Jewish concentration and extermination camps, Drancy is the only place of memory in France to feature."''Le camp de Drancy et ses gares de déportation: Bourget-Drancy et Bobigny, 20 août 1941 – 20 août 1944'', FFDJF, January 2004.

Film documentaries and books

* André Bossuroy, 2011''ICH BIN''

with the support from the Fondation Hippocrène and from the EACEA Agency of the European Commission (Programme Europe for citizens – An active European remembrance), RTBF, VRT. * William Karel, 1992. ''La Rafle du Vel-d'Hiv'', La Marche du siècle,

France 3

France 3 () is a French free-to-air public television channel and part of the France Télévisions group, which also includes France 2, France 4, France 5 and France Info.

It is made up of a network of regional television services provi ...

.

* Annette Muller, ''La petite fille du Vel' d'Hiv'', Publisher Denoël, Paris, 1991. New edition by Annette et Manek Muller, ''La petite fille du Vel' d'Hiv'', Publisher Cercil, Orléans, 2009, preface by Serge Klarsfeld, prize ''Lutèce'' (Témoignage).

* Tatiana de Rosnay

Tatiana de Rosnay (born 28 September 1961) is a French writer.

Life and career

Tatiana de Rosnay was born on 28 September 1961 in the suburbs of Paris. She is of English, French and Russians, Russian descent. Her father is French scientist Jo ...

, '' Sarah's Key (novel)'', book: St. Martin's Press, 2007, (also 2010 film)

The events form the framework of:

* '' Les Guichets du Louvre'', 1974. French film directed by Michel Mitrani.

* '' Monsieur Klein'', 1976. French film directed by Joseph Losey

Joseph Walton Losey III (; January 14, 1909 – June 22, 1984) was an American theatre and film director, producer, and screenwriter. Born in Wisconsin, he studied in Germany with Bertolt Brecht and then returned to the United States. Blacklisted ...

, much of which was shot on location. The film won the 1977 César Awards

The César Award is the national film award of France. It is delivered in the ' ceremony and was first awarded in 1976. The nominations are selected by the members of twelve categories of filmmaking professionals and supported by the French Mi ...

in the categories of Best Film, Best Director, and Best Production Design.

* '' The Round Up'' (''La Rafle''), 2010. French film directed by Roselyne Bosch and produced by Alain Goldman

Alain Goldman, also known as Ilan Goldman (born 12 January 1961) is a French film producer.

Early life

Goldman was born in Montmartre, Paris, the son of Jewish parents. His grandfather was the first representative for Universal Pictures in F ...

.

* '' Sarah's Key'', 2010. French film directed by Gilles Paquet-Brenner and produced by Stéphane Marsil.

See also

* Reparations (transitional justice) * The Holocaust in France * Timeline of deportations of French Jews to death camps * Union générale des israélites de France *Vichy France

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its t ...

References

Bibliography

* * * *Further reading

* Jean-Luc Einaudi and Maurice Rajsfus, ''Les silences de la police – 16 juillet 1942, 17 octobre 1961'', 2001, L'Esprit frappeur, (Rajsfus is an historian of the French police; the second date refers to the 1961 Paris massacre under the orders of Maurice Papon, who would later be judged for his role during Vichy in Bordeaux) * Serge Klarsfeld, ''Vichy-Auschwitz: Le rôle de Vichy dans la Solution Finale de la question Juive en France- 1942,'' Paris: Fayard, 1983. * Claude Lévy and Paul Tillard, ''La grande rafle du Vel d'Hiv,'' Paris: Editions Robert Laffont, 1992. * Maurice Rajsfus, ''Jeudi noir'', Éditions L'Harmattan. Paris, 1988. * Maurice Rajsfus, ''La Rafle du Vél d'Hiv'', Que sais-je ?, éditions PUFPrimary sources

* Instructions given by chief of police Hennequin for the raid : http://artsweb.bham.ac.uk/vichy/police.htm#Jews * Serge Klarsfeld, "Vichy-Auschwitz: Le rôle de Vichy dans la Solution Finale de la question Juive en France- 1942," Paris: Fayard, 1983. Klarsfeld's work contains nearly 300 pages of primary sources on French roundups in 1942.External links

*Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence: ''Case Study: The Vélodrome d'Hiver Round-up: July 16 and 17, 1942''

Le monument commémoratif du quai de Grenelle à Paris

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20061012122235/http://new.filter.ac.uk/database/getinsight.php?id=51 Occupied France: Commemorating the Deportation

additional photographs

French government booklet

2012 speech of President François Hollande

The Vel' d'Hiv Roundup

at the online exhibition The Holocaust in France at

Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem ( he, יָד וַשֵׁם; literally, "a memorial and a name") is Israel's official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust. It is dedicated to preserving the memory of the Jews who were murdered; honoring Jews who fought against th ...

website

The trains of the Holocaust

by Hedi Enghelberg, digital book edition, www.amazon.com, The ENG Publishing, 2010-2012 {{DEFAULTSORT:Vel Dhiv Roundup The Holocaust in France War crimes in France Vichy France 1942 in France Reparations July 1942 events 1942 in Judaism