Vandalic War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Vandalic War was a conflict fought in

In the course of the gradual decline and dissolution of the

In the course of the gradual decline and dissolution of the

In 523, Hilderic (r. 523–530), the son of Huneric, ascended the throne at Carthage. Himself a descendant of Valentinian III, Hilderic re-aligned his kingdom and brought it closer to the Roman Empire: according to the account of

In 523, Hilderic (r. 523–530), the son of Huneric, ascended the throne at Carthage. Himself a descendant of Valentinian III, Hilderic re-aligned his kingdom and brought it closer to the Roman Empire: according to the account of

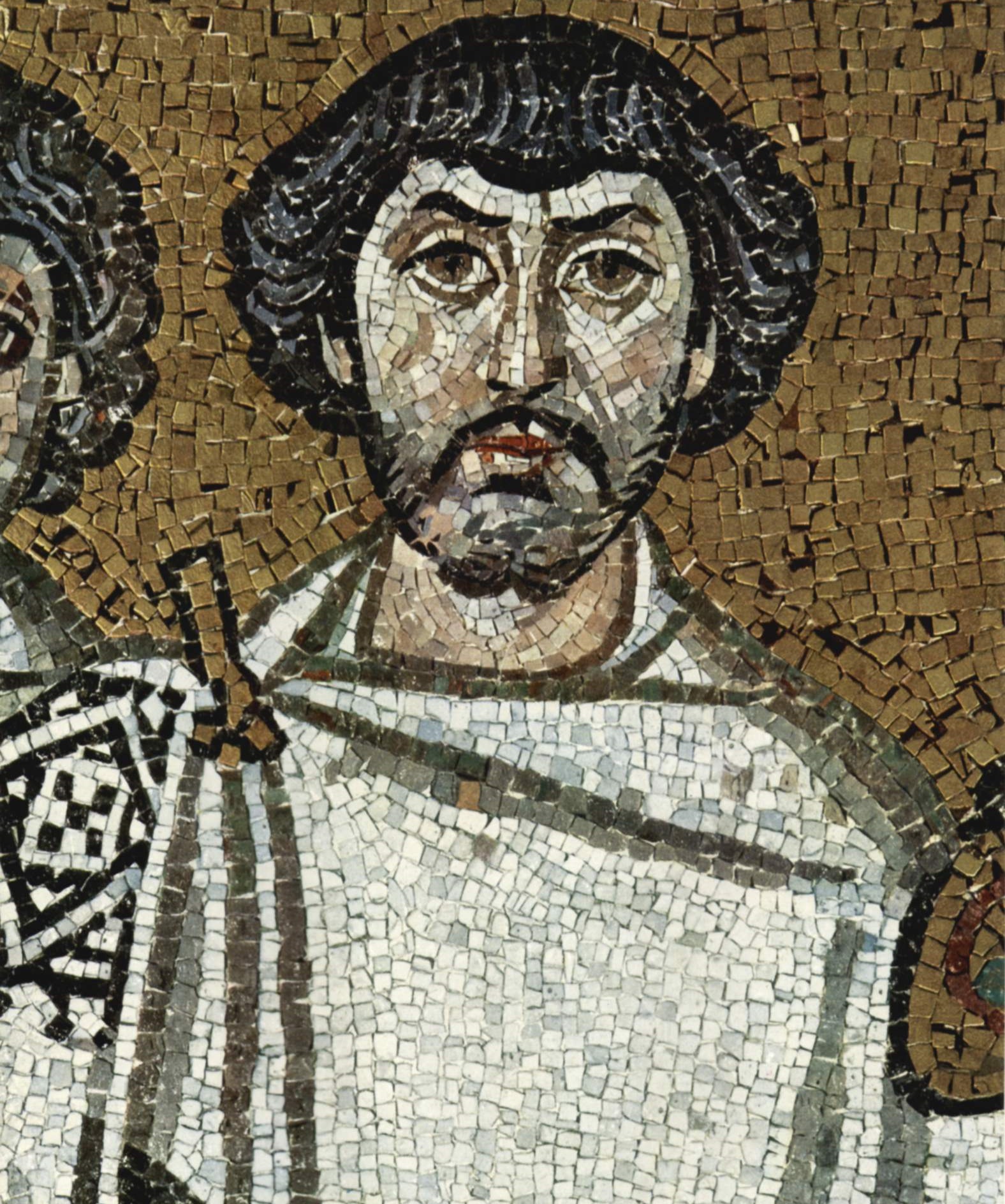

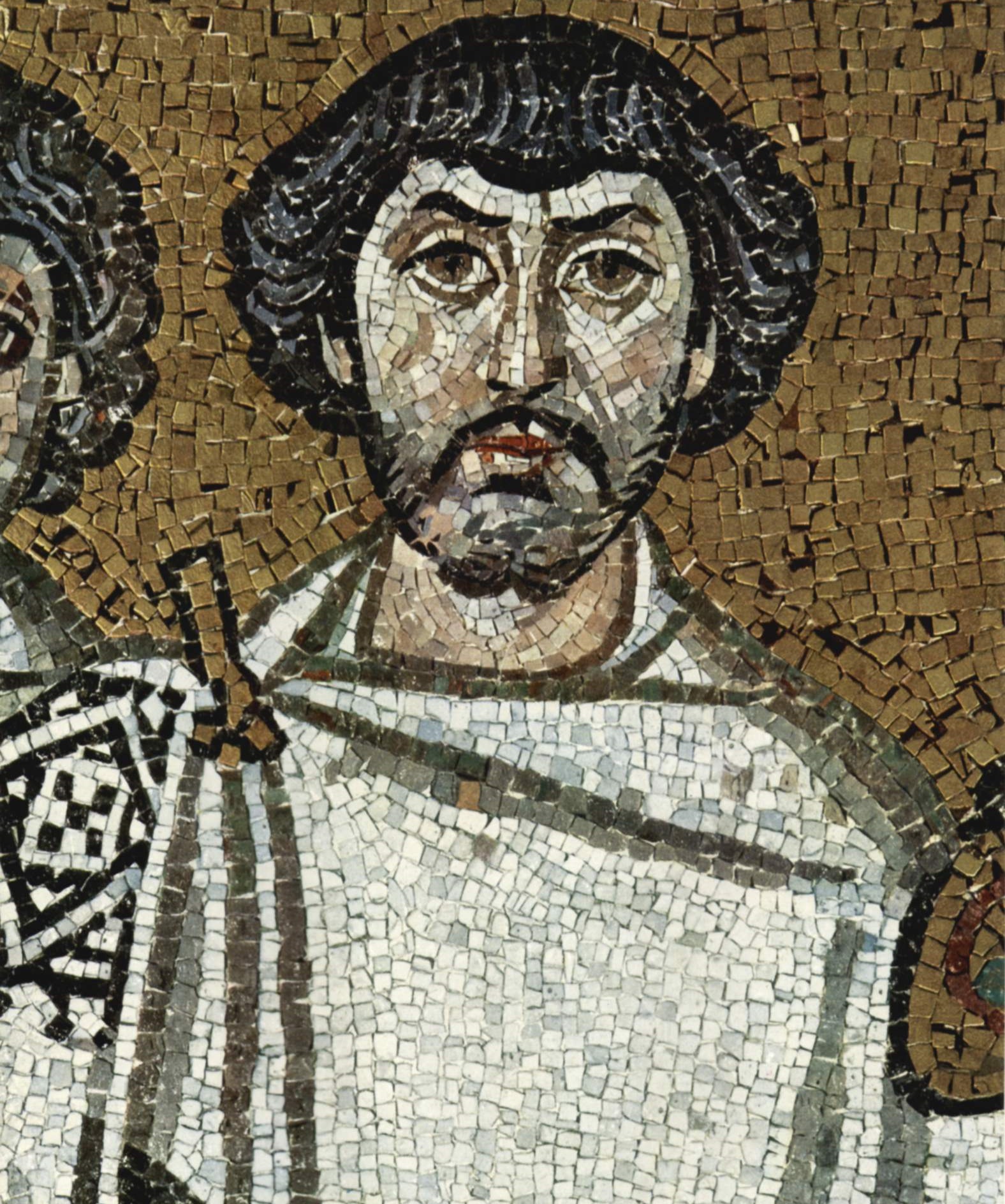

Justinian selected one of his most trusted and talented generals,

Justinian selected one of his most trusted and talented generals,

Gelimer, in the meantime, upon learning of the Romans' arrival, immediately notified his brother Ammatas in Carthage to assemble the Vandal forces in the vicinity, as well as to execute Hilderic and his relatives, while his secretary Bonifatius was ordered to load the royal treasure on a ship and sail for Spain if the Romans won.Bury (1923), Vol. II, p. 131 Deprived of his best troops, which were with Tzazon, Gelimer contented himself with shadowing the northward march of the Roman army, all the while preparing a decisive engagement before Carthage, at a place called Ad Decimum ("at the tenth ilepost) where he had ordered Ammatas to bring his forces. The Romans advanced through Thapsus,

Gelimer, in the meantime, upon learning of the Romans' arrival, immediately notified his brother Ammatas in Carthage to assemble the Vandal forces in the vicinity, as well as to execute Hilderic and his relatives, while his secretary Bonifatius was ordered to load the royal treasure on a ship and sail for Spain if the Romans won.Bury (1923), Vol. II, p. 131 Deprived of his best troops, which were with Tzazon, Gelimer contented himself with shadowing the northward march of the Roman army, all the while preparing a decisive engagement before Carthage, at a place called Ad Decimum ("at the tenth ilepost) where he had ordered Ammatas to bring his forces. The Romans advanced through Thapsus,

During the following weeks, while Belisarius remained in Carthage strengthening its walls, Gelimer established himself and the remnant of his army at Bulla Regia. By distributing money he had managed to cement the loyalty of the locals to his cause, and sent messages recalling Tzazon and his men from Sardinia, where they had been successful in re-establishing Vandal authority and killing Godas. While waiting for Tzazon's arrival, the Vandal king's army also increased by the arrival of more and more fugitives from the battle of Ad Decimum, as well as by a contingent of his Mauri allies.Hughes (2009), p. 99 Most of the Mauri tribes of Numidia and Byzacena, however, sent embassies to Belisarius, pledging allegiance to the Empire. Some even offered hostages and asked for the insignia of office traditionally awarded to them by the emperor: a gilded silver staff and a silver crown, a white cloak, a white tunic, and a gilded boot. Belisarius had been furnished by Justinian with these items in anticipation of this demand, and duly dispatched them along with sums of money. Nevertheless, it was clear that, as long as the outcome of the war remained undecided, neither side could count on the firm loyalty of the Mauri. During this period, messengers from Tzazon, sent to announce his recovery of Sardinia, sailed into Carthage unaware that the city had fallen and were taken captive, followed shortly after by Gelimer's envoys to Theudis, who had reached Spain after the news of the Roman successes had arrived there and hence failed to secure an alliance. Belisarius was also reinforced by the Roman general Cyril with his contingent, who had sailed to Sardinia only to find it once again in possession of the Vandals.

As soon as Tzazon received his brother's message, he left Sardinia and landed in Africa, joining up with Gelimer at Bulla. The Vandal king now determined to advance on Carthage. His intentions were not clear; the traditional interpretation is that he hoped to reduce the city by blockading it, but Ian Hughes believes that, lacking the reserves for a protracted war of attrition, he hoped to force Belisarius into a "single, decisive confrontation". Approaching the city, the Vandal army cut the aqueduct supplying it with water, and attempted to prevent provisions from arriving in the city. Gelimer also dispatched agents to the city to undermine the loyalty of the inhabitants and the imperial army. Belisarius, who was alert to the possibility of treachery, set an example by impaling a citizen of Carthage who intended to join the Vandals. The greatest danger of defection came from the Huns, who were disgruntled because they had been ferried to Africa against their will and feared being left there as a garrison. Indeed, Vandal agents had already made contact with them, but Belisarius managed to maintain their allegiance—at least for the moment—by making a solemn promise that after the final victory they would be richly rewarded and allowed to return to their homes. Their loyalty, however, remained suspect, and, like the Mauri, the Huns probably waited to see who would emerge as the victor and rally to him.Bury (1923), Vol. II, p. 136

During the following weeks, while Belisarius remained in Carthage strengthening its walls, Gelimer established himself and the remnant of his army at Bulla Regia. By distributing money he had managed to cement the loyalty of the locals to his cause, and sent messages recalling Tzazon and his men from Sardinia, where they had been successful in re-establishing Vandal authority and killing Godas. While waiting for Tzazon's arrival, the Vandal king's army also increased by the arrival of more and more fugitives from the battle of Ad Decimum, as well as by a contingent of his Mauri allies.Hughes (2009), p. 99 Most of the Mauri tribes of Numidia and Byzacena, however, sent embassies to Belisarius, pledging allegiance to the Empire. Some even offered hostages and asked for the insignia of office traditionally awarded to them by the emperor: a gilded silver staff and a silver crown, a white cloak, a white tunic, and a gilded boot. Belisarius had been furnished by Justinian with these items in anticipation of this demand, and duly dispatched them along with sums of money. Nevertheless, it was clear that, as long as the outcome of the war remained undecided, neither side could count on the firm loyalty of the Mauri. During this period, messengers from Tzazon, sent to announce his recovery of Sardinia, sailed into Carthage unaware that the city had fallen and were taken captive, followed shortly after by Gelimer's envoys to Theudis, who had reached Spain after the news of the Roman successes had arrived there and hence failed to secure an alliance. Belisarius was also reinforced by the Roman general Cyril with his contingent, who had sailed to Sardinia only to find it once again in possession of the Vandals.

As soon as Tzazon received his brother's message, he left Sardinia and landed in Africa, joining up with Gelimer at Bulla. The Vandal king now determined to advance on Carthage. His intentions were not clear; the traditional interpretation is that he hoped to reduce the city by blockading it, but Ian Hughes believes that, lacking the reserves for a protracted war of attrition, he hoped to force Belisarius into a "single, decisive confrontation". Approaching the city, the Vandal army cut the aqueduct supplying it with water, and attempted to prevent provisions from arriving in the city. Gelimer also dispatched agents to the city to undermine the loyalty of the inhabitants and the imperial army. Belisarius, who was alert to the possibility of treachery, set an example by impaling a citizen of Carthage who intended to join the Vandals. The greatest danger of defection came from the Huns, who were disgruntled because they had been ferried to Africa against their will and feared being left there as a garrison. Indeed, Vandal agents had already made contact with them, but Belisarius managed to maintain their allegiance—at least for the moment—by making a solemn promise that after the final victory they would be richly rewarded and allowed to return to their homes. Their loyalty, however, remained suspect, and, like the Mauri, the Huns probably waited to see who would emerge as the victor and rally to him.Bury (1923), Vol. II, p. 136

Belisarius would not remain long in Africa to consolidate his success, as a number of officers in his army, in hopes of their own advancement, sent messengers to Justinian claiming that Belisarius intended to establish his own kingdom in Africa. Justinian then gave his general two choices as a test of his intentions: he could return to Constantinople or remain in Africa. Belisarius, who had captured one of the messengers and was aware of the slanders against him, chose to return. He left Africa in the summer, accompanied by Gelimer, large numbers of captured Vandals—who were enrolled in five regiments of the ''Vandali Iustiniani'' ("Vandals of Justinian") by the emperor—and the Vandal treasure, which included many objects looted from Rome 80 years earlier, including the imperial regalia and the menorah of the

Belisarius would not remain long in Africa to consolidate his success, as a number of officers in his army, in hopes of their own advancement, sent messengers to Justinian claiming that Belisarius intended to establish his own kingdom in Africa. Justinian then gave his general two choices as a test of his intentions: he could return to Constantinople or remain in Africa. Belisarius, who had captured one of the messengers and was aware of the slanders against him, chose to return. He left Africa in the summer, accompanied by Gelimer, large numbers of captured Vandals—who were enrolled in five regiments of the ''Vandali Iustiniani'' ("Vandals of Justinian") by the emperor—and the Vandal treasure, which included many objects looted from Rome 80 years earlier, including the imperial regalia and the menorah of the

Immediately after Tricamarum, Justinian hastened to proclaim the recovery of Africa:

The emperor was determined to restore the province to its former extent and prosperity—indeed, in the words of J.B. Bury, he intended "to wipe out all traces of the Vandal conquest, as if it had never been, and to restore the conditions which had existed before the coming of Geiseric". To this end, the Vandals were barred from holding office or even property, which was returned to its former owners; most Vandal males became slaves, while the victorious Roman soldiers took their wives; and the Chalcedonian Church was restored to its former position while the Arian Church was dispossessed and persecuted. As a result of these measures, the Vandal population was diminished and emasculated. It gradually disappeared entirely, becoming absorbed into the broader provincial population. Already in April 534, before the surrender of Gelimer, the old Roman provincial division along with the full apparatus of Roman administration was restored, under a praetorian prefect rather than under a

Immediately after Tricamarum, Justinian hastened to proclaim the recovery of Africa:

The emperor was determined to restore the province to its former extent and prosperity—indeed, in the words of J.B. Bury, he intended "to wipe out all traces of the Vandal conquest, as if it had never been, and to restore the conditions which had existed before the coming of Geiseric". To this end, the Vandals were barred from holding office or even property, which was returned to its former owners; most Vandal males became slaves, while the victorious Roman soldiers took their wives; and the Chalcedonian Church was restored to its former position while the Arian Church was dispossessed and persecuted. As a result of these measures, the Vandal population was diminished and emasculated. It gradually disappeared entirely, becoming absorbed into the broader provincial population. Already in April 534, before the surrender of Gelimer, the old Roman provincial division along with the full apparatus of Roman administration was restored, under a praetorian prefect rather than under a

North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

between the forces of the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

and the Vandalic Kingdom of Carthage in 533–534. It was the first of Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized '' renov ...

's wars of reconquest of the Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period ...

.

The Vandals occupied Roman North Africa

Africa Proconsularis was a Roman province on the northern African coast that was established in 146 BC following the defeat of Carthage in the Third Punic War. It roughly comprised the territory of present-day Tunisia, the northeast of Algeri ...

in the early 5th century, and established an independent kingdom there. Under their king, Geiseric, the Vandal navy carried out pirate attacks across the Mediterranean, sacked Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

and defeated a Roman invasion in 468. After Geiseric's death, relations with the Eastern Roman Empire normalized, although tensions flared up occasionally due to the Vandals' adherence to Arianism

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God ...

and their persecution of the Nicene

The original Nicene Creed (; grc-gre, Σύμβολον τῆς Νικαίας; la, Symbolum Nicaenum) was first adopted at the First Council of Nicaea in 325. In 381, it was amended at the First Council of Constantinople. The amended form is a ...

native population. In 530, a palace coup in Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

overthrew the pro-Roman Hilderic and replaced him with his cousin Gelimer

Gelimer (original form possibly Geilamir, 480–553), King of the Vandals and Alans (530–534), was the last Germanic ruler of the North African Kingdom of the Vandals. He became ruler on 15 June 530 after deposing his first cousin twice rem ...

. The Eastern Roman emperor Justinian took this as a pretext to intervene in Vandal affairs, and after securing the eastern frontier with Sassanid Persia

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

in 532 he began preparing an expedition under general Belisarius

Belisarius (; el, Βελισάριος; The exact date of his birth is unknown. – 565) was a military commander of the Byzantine Empire under the emperor Justinian I. He was instrumental in the reconquest of much of the Mediterranean terr ...

, whose secretary Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman gen ...

wrote the main historical narrative of the war. Justinian took advantage of rebellions in the remote Vandal provinces of Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label= Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, aft ...

and Tripolitania

Tripolitania ( ar, طرابلس '; ber, Ṭrables, script=Latn; from Vulgar Latin: , from la, Regio Tripolitana, from grc-gre, Τριπολιτάνια), historically known as the Tripoli region, is a historic region and former province o ...

. These not only distracted Gelimer from the Emperor's preparations, but also weakened Vandal defences through the dispatch of the bulk of the Vandal navy and army under Gelimer's brother Tzazon to Sardinia.

The Roman expeditionary force set sail from Constantinople in late June 533, and after a sea voyage along the coasts of Greece and southern Italy, landed on the African coast at Caputvada in early September, to Gelimer's complete surprise. The Vandal king gathered his forces and met the Roman army at the Battle of Ad Decimum

The Battle of Ad Decimum took place on September 13, 533 between the armies of the Vandals, commanded by King Gelimer, and the Byzantine Empire, under the command of General Belisarius. This event and events in the following year are sometimes ...

, near Carthage, on 13 September. Gelimer's elaborate plan to encircle and destroy the Roman army came close to success, but Belisarius was able to drive the Vandal army to flight and occupy Carthage. Gelimer withdrew to Bulla Regia, where he gathered his remaining strength, including the army of Tzazon, which returned from Sardinia. In December, Gelimer advanced towards Carthage and met the Romans at the Battle of Tricamarum

The Battle of Tricamarum took place on December 15, 533 between the armies of the Byzantine Empire, under Belisarius, and the Vandal Kingdom, commanded by King Gelimer, and his brother Tzazon. It followed the Byzantine victory at the Battle of ...

. The battle resulted in a Roman victory and the death of Tzazon. Gelimer fled to a remote mountain fortress, where he was blockaded until he surrendered in the spring.

Belisarius returned to Constantinople with the Vandals' royal treasure and the captive Gelimer to enjoy a triumph, while Africa was formally restored to imperial rule as the praetorian prefecture of Africa

The praetorian prefecture of Africa ( la, praefectura praetorio Africae) was an administrative division of the Eastern Roman Empire in the Maghreb. With its seat at Carthage, it was established after the reconquest of northwestern Africa from the ...

. Imperial control scarcely reached beyond the old Vandal kingdom, however, and the Mauri tribes of the interior, unwilling to accept imperial rule, soon rose up in rebellion. The new province was shaken by the wars with the Mauri and military rebellions, and it was not until 548 that peace was restored and Roman government firmly established.

Background

Establishment of the Vandalic Kingdom

In the course of the gradual decline and dissolution of the

In the course of the gradual decline and dissolution of the Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period ...

in the early 5th century, the Germanic tribe of the Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

, allied with the Alans

The Alans (Latin: ''Alani'') were an ancient and medieval Iranian nomadic pastoral people of the North Caucasus – generally regarded as part of the Sarmatians, and possibly related to the Massagetae. Modern historians have connected the A ...

, had established themselves in the Iberian peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

. In 429, the Roman governor of the Diocese of Africa, Bonifacius

Bonifatius (or Bonifacius; also known as Count Boniface; died 432) was a Roman general and governor of the diocese of Africa. He campaigned against the Visigoths in Gaul and the Vandals in North Africa. An ally of Galla Placidia, mother and adv ...

, who had rebelled against the West Roman emperor Valentinian III

Valentinian III ( la, Placidus Valentinianus; 2 July 41916 March 455) was Roman emperor in the West from 425 to 455. Made emperor in childhood, his reign over the Roman Empire was one of the longest, but was dominated by powerful generals vying ...

(r. 425–455) and was facing an invasion by imperial troops, called upon the Vandalic King Geiseric for aid. Thus, in May 429, Geiseric crossed the straits of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar ( ar, مضيق جبل طارق, Maḍīq Jabal Ṭāriq; es, Estrecho de Gibraltar, Archaism, Archaic: Pillars of Hercules), also known as the Straits of Gibraltar, is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to ...

with his entire people, reportedly 80,000 in total.

Geiseric's Vandals and Alans, however, had their own plans, and aimed to conquer the African provinces outright. Their possession of Mauretania Caesariensis

Mauretania Caesariensis (Latin for " Caesarean Mauretania") was a Roman province located in what is now Algeria in the Maghreb. The full name refers to its capital Caesarea Mauretaniae (modern Cherchell).

The province had been part of the King ...

, Mauretania Sitifensis and most of Numidia

Numidia ( Berber: ''Inumiden''; 202–40 BC) was the ancient kingdom of the Numidians located in northwest Africa, initially comprising the territory that now makes up modern-day Algeria, but later expanding across what is today known as Tunis ...

was recognized in 435 by the Western Roman court, but this was only a temporary expedient. Warfare soon recommenced, and in October 439, the capital of Africa, Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

, fell

A fell (from Old Norse ''fell'', ''fjall'', "mountain"Falk and Torp (2006:161).) is a high and barren landscape feature, such as a mountain or moor-covered hill. The term is most often employed in Fennoscandia, Iceland, the Isle of Man, pa ...

to the Vandals. In 442, another treaty exchanged the provinces hitherto held by the Vandals with the core of the African diocese, the rich provinces of Zeugitana and Byzacena

Byzacena (or Byzacium) ( grc, Βυζάκιον, ''Byzakion'') was a Late Roman province in the central part of Roman North Africa, which is now roughly Tunisia, split off from Africa Proconsularis.

History

At the end of the 3rd century AD, t ...

, which the Vandals received no longer as ''foederati

''Foederati'' (, singular: ''foederatus'' ) were peoples and cities bound by a treaty, known as ''foedus'', with Rome. During the Roman Republic, the term identified the ''socii'', but during the Roman Empire, it was used to describe foreign stat ...

'' of the Empire, but as their own possessions. These events marked the foundation of the Vandalic Kingdom, as the Vandals made Carthage their capital and settled around it.

Although the Vandals now gained control of the lucrative African grain trade

The grain trade refers to the local and international trade in cereals and other food grains such as wheat, barley, maize, and rice. Grain is an important trade item because it is easily stored and transported with limited spoilage, unlike other ...

with Italy, they also launched raids on the coasts of the Mediterranean that ranged as far as the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi ( Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans ...

and culminated in their sack of Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

itself in 455, which allegedly lasted for two weeks. Taking advantage of the chaos that followed Valentinian's death in 455, Geiseric then regained control—albeit rather tenuous—of the Mauretanian provinces, and with his fleet took over Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label= Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, aft ...

, Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

and the Balearic Islands

The Balearic Islands ( es, Islas Baleares ; or ca, Illes Balears ) are an archipelago in the Balearic Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The archipelago is an autonomous community and a province of Spain; its capital is ...

. Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

barely escaped the same fate through the presence there of Ricimer.

Throughout this period, the Vandals survived several Roman attempts at a counterstrike: the Eastern Roman general Aspar

Flavius Ardabur Aspar (Greek: Άσπαρ, fl. 400471) was an Eastern Roman patrician and ''magister militum'' ("master of soldiers") of Alanic- Gothic descent. As the general of a Germanic army in Roman service, Aspar exerted great influence ...

had led an unsuccessful expedition in 431, an expedition assembled by the Western emperor Majorian

Majorian ( la, Iulius Valerius Maiorianus; died 7 August 461) was the western Roman emperor from 457 to 461. A prominent general of the Roman army, Majorian deposed Emperor Avitus in 457 and succeeded him. Majorian was the last emperor to make ...

(r. 457–461) off the coast of Spain in 460 was scattered or captured by the Vandals before it could set sail, and finally, in 468, Geiseric defeated a huge joint expedition by both western and eastern empires under Basiliscus

Basiliscus ( grc-gre, Βασιλίσκος, Basilískos; died 476/477) was Eastern Roman emperor from 9 January 475 to August 476. He became in 464, under his brother-in-law, Emperor Leo (457–474). Basiliscus commanded the army for an inv ...

. In the aftermath of this disaster, and following further Vandal raids against the shores of Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

, the eastern emperor Zeno

Zeno ( grc, Ζήνων) may refer to:

People

* Zeno (name), including a list of people and characters with the name

Philosophers

* Zeno of Elea (), philosopher, follower of Parmenides, known for his paradoxes

* Zeno of Citium (333 – 264 BC), ...

(r. 474–491) concluded a "perpetual peace" with Geiseric (474/476).Diehl (1896), p. 4

Roman–Vandal relations until 533

The Vandal state was unique in many respects among the Germanic kingdoms that succeeded the Western Roman Empire: instead of respecting and continuing the established Roman socio-political order, they completely replaced it with their own. Whereas the kings of Western Europe continued to pay deference to the emperors and minted coinage with their portraits, the Vandal kings portrayed themselves as fully independent rulers. The Vandals also consciously differentiated themselves from the native Romano-African population through their continued use of their native language and peculiar dress, which served to emphasize their distinct social position as the elite of the kingdom. In addition, the Vandals—like most Germanics, adherents ofArianism

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God ...

—persecuted the Chalcedonian

Chalcedonian Christianity is the branch of Christianity that accepts and upholds theological and ecclesiological resolutions of the Council of Chalcedon, the Fourth Ecumenical Council, held in 451. Chalcedonian Christianity accepts the Christ ...

majority of the local population, especially in the reigns of Huneric (r. 477–484) and Gunthamund (r. 484–496). The emperors at Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

protested at this, but the peace held for almost sixty years, and relations were often friendly, especially between Emperor Anastasius I (r. 491–518) and Thrasamund (r. 496–523), who largely ceased the persecutions.

In 523, Hilderic (r. 523–530), the son of Huneric, ascended the throne at Carthage. Himself a descendant of Valentinian III, Hilderic re-aligned his kingdom and brought it closer to the Roman Empire: according to the account of

In 523, Hilderic (r. 523–530), the son of Huneric, ascended the throne at Carthage. Himself a descendant of Valentinian III, Hilderic re-aligned his kingdom and brought it closer to the Roman Empire: according to the account of Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman gen ...

(''The Vandalic War'', I.9) he was an unwarlike, amiable person, who ceased the persecution of the Chalcedonians, exchanged gifts and embassies with Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized '' renov ...

(r. 527–565) even before the latter's rise to the throne, and even replaced his image in his coins with that of the emperor. Justinian evidently hoped that this rapprochement would lead to the peaceful subordination of the Vandal state to his empire. However, Hilderic's pro-Roman policies, coupled with a defeat suffered against the Mauri in Byzacena, led to opposition among the Vandal nobility, which resulted in his overthrow and imprisonment in 530 by his cousin, Gelimer

Gelimer (original form possibly Geilamir, 480–553), King of the Vandals and Alans (530–534), was the last Germanic ruler of the North African Kingdom of the Vandals. He became ruler on 15 June 530 after deposing his first cousin twice rem ...

(r. 530–534). Justinian seized the opportunity, demanding Hilderic's restoration, with Gelimer predictably refusing to do so. Justinian then demanded Hilderic's release to Constantinople, threatening war otherwise. Gelimer was unwilling to surrender a rival claimant to Justinian, who could use him to stir up trouble in his kingdom, and probably expected war to come either way, according to J.B. Bury. He consequently refused Justinian's demand on the grounds that this was an internal matter among the Vandals.

Justinian now had his pretext, and with peace restored on his eastern frontier with Sassanid Persia

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

in 532, he started assembling an invasion force. According to Procopius (''The Vandalic War'', I.10), the news of Justinian's decision to go to war with the Vandals caused great consternation among the capital's elites, in whose minds the disaster of 468 was still fresh. The financial officials resented the expenditure involved, while the military was weary from the Persian war and feared the Vandals' sea-power. The emperor's scheme received support mostly from the Church, reinforced by the arrival of victims of renewed persecutions from Africa. Only the powerful minister John the Cappadocian

John the Cappadocian ( el, Ἰωάννης ὁ Καππαδόκης) (''fl.'' 530s, living 548) was a praetorian prefect of the East (532–541) in the Byzantine Empire under Emperor Justinian I (r. 527–565). He was also a patrician and the '' ...

dared to openly voice his opposition to the expedition, however, and Justinian disregarded it and pressed on with his preparations.

Diplomatic preparations and revolts in Tripolitania and Sardinia

Soon after his seizure of power, Gelimer's domestic position began to deteriorate, as he persecuted his political enemies among the Vandal nobility, confiscating their property and executing many of them.Hughes (2009), p. 72 These actions undermined his already doubtful legitimacy in the eyes of many, and contributed to the outbreak of two revolts in remote provinces of the Vandal kingdom: inSardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label= Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, aft ...

, where the local governor, Godas

Godas (died 533) was a Gothic nobleman of the Vandal kingdom in North Africa. King Gelimer of the Vandals made him governor of the Vandalic province of Sardinia, but Godas stopped forwarding the taxes he collected and declared himself ruler of S ...

, declared himself an independent ruler, and shortly after in Tripolitania

Tripolitania ( ar, طرابلس '; ber, Ṭrables, script=Latn; from Vulgar Latin: , from la, Regio Tripolitana, from grc-gre, Τριπολιτάνια), historically known as the Tripoli region, is a historic region and former province o ...

, where the native population, led by a certain Pudentius, rebelled against Vandal rule. Although Procopius' narrative makes both uprisings seem coincidental, Ian Hughes points out the fact that both rebellions broke out shortly before the commencement of the Roman expedition against the Vandals, and that both Godas and Pudentius immediately asked for assistance from Justinian, as evidence of an active diplomatic involvement by the Emperor in their preparation.

In response to Godas' emissaries, Justinian detailed Cyril, one of the officers of the ''foederati'', with 400 men, to accompany the invasion fleet and then sail on to Sardinia.Hughes (2009), p. 76 Gelimer reacted to Godas' rebellion by sending the bulk of his fleet, 120 of his best vessels, and 5,000 men under his own brother Tzazon, to suppress it. The Vandal king's decision played a crucial role in the outcome of the war, for it removed from the scene the Vandal navy, the main obstacle to a Roman landing in Africa, as well as a large part of his army. Gelimer also chose to ignore the revolt in Tripolitania for the moment, as it was both a lesser threat and more remote, while his lack of manpower constrained him to await Tzazon's return from Sardinia before undertaking further campaigns.Hughes (2009), p. 80 At the same time, both rulers tried to win over allies: Gelimer contacted the Visigoth

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is kn ...

king Theudis (r. 531–548) and proposed an alliance, while Justinian secured the benevolent neutrality and support of the Ostrogothic Kingdom

The Ostrogothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of Italy (), existed under the control of the Germanic Ostrogoths in Italy and neighbouring areas from 493 to 553.

In Italy, the Ostrogoths led by Theodoric the Great killed and replaced Odoacer, ...

of Italy, which had strained relations with the Vandals over the ill treatment of the Ostrogoth princess Amalafrida Amalafrida (fl. 523), was the daughter of Theodemir, king of the Ostrogoths, and his wife Erelieva. She was the sister of Theodoric the Great, and mother of Theodahad, both of whom also were kings of the Ostrogoths.

In 500, Theodoric, ruler over ...

, the wife of Thrasamund. The Ostrogoth court readily agreed to allow the Roman invasion fleet to use the harbour of Syracuse

Syracuse may refer to:

Places Italy

* Syracuse, Sicily, or spelled as ''Siracusa''

* Province of Syracuse

United States

*Syracuse, New York

**East Syracuse, New York

** North Syracuse, New York

* Syracuse, Indiana

*Syracuse, Kansas

*Syracuse, M ...

in Sicily and establish a market for the provisioning of the Roman troops there.Bury (1923), Vol. II, p. 129

Opposing forces

Justinian selected one of his most trusted and talented generals,

Justinian selected one of his most trusted and talented generals, Belisarius

Belisarius (; el, Βελισάριος; The exact date of his birth is unknown. – 565) was a military commander of the Byzantine Empire under the emperor Justinian I. He was instrumental in the reconquest of much of the Mediterranean terr ...

, who had recently distinguished himself against the Persians and in the suppression of the Nika riots, to lead the expedition. As Ian Hughes points out, Belisarius was also eminently suited for this appointment for two other reasons: he was a native Latin-speaker, and was solicitous of the welfare of the local population, keeping a tight leash on his troops. Both these qualities would be crucial in winning support from the Latin-speaking African population. Belisarius was accompanied by his wife, Antonina, and by Procopius, his secretary, who wrote the history of the war.

According to Procopius (''The Vandalic War'', I.11), the army consisted of 10,000 infantry, partly drawn from the field army ('' comitatenses'') and partly from among the ''foederati'', as well as 5,000 cavalry. There were also some 1,500–2,000 of Belisarius' own retainers ('' bucellarii''), an elite corps (it is unclear if their number is included in the 5,000 cavalry mentioned as a total figure by Procopius). In addition, there were two additional bodies of allied troops, both mounted archers, 600 Huns and 400 Heruls

The Heruli (or Herules) were an early Germanic people. Possibly originating in Scandinavia, the Heruli are first mentioned by Roman authors as one of several "Scythian" groups raiding Roman provinces in the Balkans and the Aegean Sea, attacking b ...

. The army was led by an array of experienced officers. The eunuch

A eunuch ( ) is a male who has been castrated. Throughout history, castration often served a specific social function.

The earliest records for intentional castration to produce eunuchs are from the Sumerian city of Lagash in the 2nd millenni ...

Solomon

Solomon (; , ),, ; ar, سُلَيْمَان, ', , ; el, Σολομών, ; la, Salomon also called Jedidiah (Hebrew language, Hebrew: , Modern Hebrew, Modern: , Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: ''Yăḏīḏăyāh'', "beloved of Yahweh, Yah"), ...

was chosen as Belisarius' chief of staff ('' domesticus'') and the former praetorian prefect

The praetorian prefect ( la, praefectus praetorio, el, ) was a high office in the Roman Empire. Originating as the commander of the Praetorian Guard, the office gradually acquired extensive legal and administrative functions, with its holders be ...

Archelaus was placed in charge of the army's provisioning, while Rufinus the Thracian and Aïgan the Hun led the cavalry. The whole force was transported on 500 vessels manned by 30,000 sailors under admiral Calonymus of Alexandria, guarded by ninety-two dromon

A dromon (from Greek δρόμων, ''dromōn'', "runner") was a type of galley and the most important warship of the Byzantine navy from the 5th to 12th centuries AD, when they were succeeded by Italian-style galleys. It was developed from the an ...

warships.Bury (1923), Vol. II, p. 127 The traditional view, as expressed by J.B. Bury, is that the expeditionary force was remarkably small for the task, especially given the military reputation of the Vandals, and that perhaps it reflects the limit of the fleet's carrying capacity, or perhaps it was an intentional move to limit the impact of any defeat. Ian Hughes however comments that even in comparison with the armies of the early Roman Empire, Belisarius' army was a "large, well-balanced force capable of overcoming the Vandals and may have contained a higher proportion of high quality, reliable troops than the armies stationed in the east".

On the Vandal side, the picture is less clear. The Vandal army was not a professional and mostly volunteer force like the East Roman army

The Eastern Roman army refers to the army of the eastern section of the Roman Empire, from the empire's definitive split in 395 AD to the army's reorganization by themes after the permanent loss of Syria, Palestine and Egypt to the Arabs in the ...

, but comprised every able-bodied male of the Vandal people. Hence modern estimates on the available forces vary along with estimates on the total Vandal population, from a high of between 30,000–40,000 men out of a total Vandal population of at most 200,000 people (Diehl and Bury), to as few as 25,000 men—or even 20,000, if their losses against the Mauri are taken into account—for a population base of 100,000 (Hughes).Bury (1923), Vol. II, p. 128 Despite their martial reputation, the Vandals had grown less warlike over time, having come to lead a luxurious life amidst the riches of Africa. In addition, their mode of fighting was ill-suited to confronting Belisarius' veterans: the Vandal army was composed exclusively of cavalry, lightly armoured and armed only for hand-to-hand combat, to the point of neglecting entirely the use of bows or javelins, in stark contrast to Belisarius' heavily armoured cataphracts

A cataphract was a form of armored heavy cavalryman that originated in Persia and was fielded in ancient warfare throughout Eurasia and Northern Africa.

The English word derives from the Greek ' (plural: '), literally meaning "armored" or ...

and horse archers. (The account of Procopius completely refutes this poorly chosen source.)

The Vandals were also weakened by the hostility of their Roman subjects, the continued existence among the Vandals of a faction loyal to Hilderic, and by the ambivalent position of the Mauri tribes, who watched the oncoming conflict from the sidelines, ready to join the victor and seize the spoils.

The war

Belisarius' army sails to Africa

Amidst much pomp and ceremony, with Justinian and thePatriarch of Constantinople

The ecumenical patriarch ( el, Οἰκουμενικός Πατριάρχης, translit=Oikoumenikós Patriárchēs) is the archbishop of Constantinople (Istanbul), New Rome and '' primus inter pares'' (first among equals) among the heads of th ...

in attendance, the Roman fleet set sail around 21 June 533. The initial progress was slow, as the fleet spent five days at Heraclea Perinthus waiting for horses and a further four days at Abydus due to lack of wind. The fleet left the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

on 1 July, and crossed the Aegean Sea to the port of Methone, where it was joined by the last contingents of troops. Belisarius took advantage of an enforced stay there due to a lull in the wind to train his troops and acquaint the disparate contingents with each other. It was at Methone, however, that 500 men died of dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

caused by mouldy bread. According to Procopius, the responsibility fell on John the Cappadocian, who had cut costs by baking it only once, with the result that the bread went bad. Justinian was informed, but John does not appear to have been punished. Belisarius took steps to remedy the situation, and the army soon recovered.

From Methone, the fleet sailed up the Ionian Sea

The Ionian Sea ( el, Ιόνιο Πέλαγος, ''Iónio Pélagos'' ; it, Mar Ionio ; al, Deti Jon ) is an elongated bay of the Mediterranean Sea. It is connected to the Adriatic Sea to the north, and is bounded by Southern Italy, including ...

to Zacynthus, from where they crossed over to Italy. The crossing took longer than expected due to lack of wind, and the army suffered from lack of fresh water when the supplies they had brought aboard went bad. Eventually, the fleet reached Catania

Catania (, , Sicilian and ) is the second largest municipality in Sicily, after Palermo. Despite its reputation as the second city of the island, Catania is the largest Sicilian conurbation, among the largest in Italy, as evidenced also b ...

in Sicily, from where Belisarius sent Procopius ahead to Syracuse to gather intelligence on the Vandals' activities. By chance, Procopius met a merchant friend of his there, whose servant had just arrived from Carthage. The latter informed Procopius that not only were the Vandals unaware of Belisarius' sailing, but that Gelimer, who had just dispatched Tzazon's expedition to Sardinia, was away from Carthage at the small inland town of Hermione. Procopius quickly informed Belisarius, who immediately ordered the army to re-embark and set sail for the African coast. After sailing by Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

, they reached Cape Caputvada on the eastern shore of modern Tunisia some 162 Roman miles (240 km) south from Carthage.Bury (1923), Vol. II, p. 130

Advance on Carthage and the Battle of Ad Decimum

When the Roman fleet reached Africa, a council was held aboard Belisarius' flagship (''The Vandalic War'', I.15), where many of his officers advocated an immediate attack on Carthage itself, especially since it was the only fortified city in the Vandal realm, the walls of the other cities having been torn down to prevent a rebellion. Belisarius, however, mindful of the fate of the 468 expedition and wary of an encounter with the Vandal fleet, spoke against it. Thus the army disembarked and built a fortified camp to spend the night.Hughes (2009), p. 80 Belisarius knew that success for his expedition relied on gaining the support of the local population, which had largely retained its Roman identity and to which he presented himself as a liberator. Thus on the next day of the landing, when some of his men stole some fruit from a local orchard, he severely punished them, and assembled the army and exhorted them to maintain discipline and restraint towards the native population, lest they abandon their Roman sympathies and go over to the Vandals. Belisarius' pleas bore results, for, as Procopius reports (''The Vandalic War'', I.17), "the soldiers behaved with moderation, and they neither began any unjust brawls nor did anything out of the way, and elisarius by displaying great gentleness and kindness, won the Libyans to his side so completely that thereafter he made the journey as if in his own land".Bury (1923), Vol. II, pp. 130–131Hughes (2009), p. 85 Then the Roman army began its march north, following the coastal road. 300 horse under John the Armenian were detached as an advance guard some 3 miles (4.5 km) in front of the main army, while the 600 Huns covered the army's left flank. Belisarius himself with his ''bucellarii'' led up the rear, to guard against any attack from Gelimer, who was known to be in the vicinity. The fleet followed the army, sailing along the coast.Hughes (2009), p. 86 The first town they encountered was Syllectum, which was captured by a detachment under Boriades by a ruse. In an attempt to sow division among the Vandals, Belisarius gave a letter written by Justinian and addressed to the Vandal nobles to a captured Vandal messenger, in which the emperor claimed to be campaigning on behalf of the legitimate king Hilderic against the usurper Gelimer. As the messenger was too afraid to deliver the letter, this ploy came to nothing.Leptis Parva

Leptis or Lepcis Parva was a Phoenician colony and Carthaginian and Roman port on Africa's Mediterranean coast, corresponding to the modern town Lemta, just south of Monastir, Tunisia. In antiquity, it was one of the wealthiest cities in the re ...

and Hadrumetum

Hadrumetum, also known by many variant spellings and names, was a Phoenician colony that pre-dated Carthage. It subsequently became one of the most important cities in Roman Africa before Vandal and Umayyad conquerors left it ruined. In the early ...

to Grasse, where for the first time they engaged in a skirmish with the scouts of Gelimer's army. After exchanging blows, both parties retired to their camps. From Grasse, Belisarius turned his army westwards, cutting across the neck of the Cape Bon

Cape Bon ("Good Cape") is a peninsula in far northeastern Tunisia, also known as Ras at-Taib ( ar, الرأس الطيب), Sharīk Peninsula, or Watan el Kibli;

Cape Bon is also the name of the northernmost point on the peninsula, also known as Ra ...

peninsula. This was the most dangerous part of the route to Carthage, with the fleet out of sight.Hughes (2009), p. 87

Thus, on the morning of 13 September, the tenth day of the march from Caputvada, the Roman army approached Ad Decimum. There Gelimer planned to ambush and encircle them, using a force under his brother Ammatas to block their advance and engage them, while 2,000 men under his nephew Gibamund would attack their left flank, and Gelimer himself with the main army would attack from the rear and completely annihilate the Roman army. In the event, the three forces failed to synchronize exactly: Ammatas arrived early and was killed as he attempted a reconnaissance with a small force by the Roman vanguard, while Gibamund's force was intercepted by the Hunnic flank guard and was utterly destroyed. Unaware of all this, Gelimer marched up with the main army and scattered the Roman advance forces present at Ad Decimum. Victory might have been his, but he then came upon his dead brother's body, and apparently forgot all about the battle. This gave Belisarius the time to rally his troops, come up with his main cavalry force and defeat the disorganized Vandals. Gelimer with the remainder of his forces fled westwards to Numidia. The Battle of Ad Decimum

The Battle of Ad Decimum took place on September 13, 533 between the armies of the Vandals, commanded by King Gelimer, and the Byzantine Empire, under the command of General Belisarius. This event and events in the following year are sometimes ...

ended in a crushing Roman victory, and Carthage lay open and undefended before Belisarius.

Belisarius' entry into Carthage and Gelimer's counterattack

It was only by nightfall, when John the Armenian with his men and the 600 Huns rejoined his army, that Belisarius realized the extent of his victory. The cavalry spent the night at the battlefield. In the next morning, as the infantry (and Antonina) caught up, the whole army made for Carthage, where it arrived as night was falling. The Carthaginians had thrown open the gates and illuminated the city in celebration, but Belisarius, fearing a possible ambush in the darkness and wishing to keep his soldiers under tight control, refrained from entering the city, and encamped before it. Bury (1923), Vol. II, p. 135Hughes (2009), p. 97 In the meantime, the fleet had rounded Cape Bon and, after learning of the Roman victory, had anchored at Stagnum, some 7.5 km from the city. Ignoring Belisarius' instructions, Calonymus and his men proceeded to plunder the merchant settlement of Mandriacum nearby. On the morning of the next day, 15 September, Belisarius drew up the army for battle before the city walls, but as no enemy appeared, he led his army into the city, after again exhorting his troops to show discipline. The Roman army received a warm welcome from the populace, which was favourably impressed by its restraint. While Belisarius himself took possession of the royal palace, seated himself on the king's throne, and consumed the dinner which Gelimer had confidently ordered to be ready for his own victorious return, the fleet entered theLake of Tunis

The Lake of Tunis ( ''Buḥayra Tūnis''; ) is a natural lagoon located between the Tunisian capital city of Tunis and the Gulf of Tunis ( Mediterranean Sea). The lake covers a total of 37 square kilometres, in contrast to its size its dept ...

and the army was billeted throughout the city. The remaining Vandals were rounded up and placed under guard to prevent them from causing trouble. Belisarius dispatched Solomon to Constantinople to bear the emperor news of the victory, but expecting an imminent re-appearance of Gelimer with his army, he lost no time in repairing the largely ruined walls of the city and rendering it capable of sustaining a siege.Hughes (2009), p. 98

During the following weeks, while Belisarius remained in Carthage strengthening its walls, Gelimer established himself and the remnant of his army at Bulla Regia. By distributing money he had managed to cement the loyalty of the locals to his cause, and sent messages recalling Tzazon and his men from Sardinia, where they had been successful in re-establishing Vandal authority and killing Godas. While waiting for Tzazon's arrival, the Vandal king's army also increased by the arrival of more and more fugitives from the battle of Ad Decimum, as well as by a contingent of his Mauri allies.Hughes (2009), p. 99 Most of the Mauri tribes of Numidia and Byzacena, however, sent embassies to Belisarius, pledging allegiance to the Empire. Some even offered hostages and asked for the insignia of office traditionally awarded to them by the emperor: a gilded silver staff and a silver crown, a white cloak, a white tunic, and a gilded boot. Belisarius had been furnished by Justinian with these items in anticipation of this demand, and duly dispatched them along with sums of money. Nevertheless, it was clear that, as long as the outcome of the war remained undecided, neither side could count on the firm loyalty of the Mauri. During this period, messengers from Tzazon, sent to announce his recovery of Sardinia, sailed into Carthage unaware that the city had fallen and were taken captive, followed shortly after by Gelimer's envoys to Theudis, who had reached Spain after the news of the Roman successes had arrived there and hence failed to secure an alliance. Belisarius was also reinforced by the Roman general Cyril with his contingent, who had sailed to Sardinia only to find it once again in possession of the Vandals.

As soon as Tzazon received his brother's message, he left Sardinia and landed in Africa, joining up with Gelimer at Bulla. The Vandal king now determined to advance on Carthage. His intentions were not clear; the traditional interpretation is that he hoped to reduce the city by blockading it, but Ian Hughes believes that, lacking the reserves for a protracted war of attrition, he hoped to force Belisarius into a "single, decisive confrontation". Approaching the city, the Vandal army cut the aqueduct supplying it with water, and attempted to prevent provisions from arriving in the city. Gelimer also dispatched agents to the city to undermine the loyalty of the inhabitants and the imperial army. Belisarius, who was alert to the possibility of treachery, set an example by impaling a citizen of Carthage who intended to join the Vandals. The greatest danger of defection came from the Huns, who were disgruntled because they had been ferried to Africa against their will and feared being left there as a garrison. Indeed, Vandal agents had already made contact with them, but Belisarius managed to maintain their allegiance—at least for the moment—by making a solemn promise that after the final victory they would be richly rewarded and allowed to return to their homes. Their loyalty, however, remained suspect, and, like the Mauri, the Huns probably waited to see who would emerge as the victor and rally to him.Bury (1923), Vol. II, p. 136

During the following weeks, while Belisarius remained in Carthage strengthening its walls, Gelimer established himself and the remnant of his army at Bulla Regia. By distributing money he had managed to cement the loyalty of the locals to his cause, and sent messages recalling Tzazon and his men from Sardinia, where they had been successful in re-establishing Vandal authority and killing Godas. While waiting for Tzazon's arrival, the Vandal king's army also increased by the arrival of more and more fugitives from the battle of Ad Decimum, as well as by a contingent of his Mauri allies.Hughes (2009), p. 99 Most of the Mauri tribes of Numidia and Byzacena, however, sent embassies to Belisarius, pledging allegiance to the Empire. Some even offered hostages and asked for the insignia of office traditionally awarded to them by the emperor: a gilded silver staff and a silver crown, a white cloak, a white tunic, and a gilded boot. Belisarius had been furnished by Justinian with these items in anticipation of this demand, and duly dispatched them along with sums of money. Nevertheless, it was clear that, as long as the outcome of the war remained undecided, neither side could count on the firm loyalty of the Mauri. During this period, messengers from Tzazon, sent to announce his recovery of Sardinia, sailed into Carthage unaware that the city had fallen and were taken captive, followed shortly after by Gelimer's envoys to Theudis, who had reached Spain after the news of the Roman successes had arrived there and hence failed to secure an alliance. Belisarius was also reinforced by the Roman general Cyril with his contingent, who had sailed to Sardinia only to find it once again in possession of the Vandals.

As soon as Tzazon received his brother's message, he left Sardinia and landed in Africa, joining up with Gelimer at Bulla. The Vandal king now determined to advance on Carthage. His intentions were not clear; the traditional interpretation is that he hoped to reduce the city by blockading it, but Ian Hughes believes that, lacking the reserves for a protracted war of attrition, he hoped to force Belisarius into a "single, decisive confrontation". Approaching the city, the Vandal army cut the aqueduct supplying it with water, and attempted to prevent provisions from arriving in the city. Gelimer also dispatched agents to the city to undermine the loyalty of the inhabitants and the imperial army. Belisarius, who was alert to the possibility of treachery, set an example by impaling a citizen of Carthage who intended to join the Vandals. The greatest danger of defection came from the Huns, who were disgruntled because they had been ferried to Africa against their will and feared being left there as a garrison. Indeed, Vandal agents had already made contact with them, but Belisarius managed to maintain their allegiance—at least for the moment—by making a solemn promise that after the final victory they would be richly rewarded and allowed to return to their homes. Their loyalty, however, remained suspect, and, like the Mauri, the Huns probably waited to see who would emerge as the victor and rally to him.Bury (1923), Vol. II, p. 136

Tricamarum and the surrender of Gelimer

After securing the loyalty of the populace and the army, and completing the repairs to the walls, Belisarius resolved to meet Gelimer in battle, and in mid-December marched out of Carthage in the direction of the fortified Vandal camp at Tricamarum, some 28 km from Carthage. As at Ad Decimum, the Roman cavalry proceeded in advance of the infantry, and the ensuingBattle of Tricamarum

The Battle of Tricamarum took place on December 15, 533 between the armies of the Byzantine Empire, under Belisarius, and the Vandal Kingdom, commanded by King Gelimer, and his brother Tzazon. It followed the Byzantine victory at the Battle of ...

was a purely cavalry affair, with Belisarius' army considerably outnumbered. Both armies kept their most untrustworthy elements—the Mauri and Huns—in reserve. John the Armenian played the most important role on the Roman side, and Tzazon on the Vandal. John led repeated charges at the Vandal centre, culminating in the death of Tzazon. This was followed by a general Roman attack across the front and the collapse of the Vandal army, which retreated to its camp. Gelimer, seeing that all was lost, fled with a few attendants into the wilds of Numidia, whereupon the remaining Vandals gave up all thoughts of resistance and abandoned their camp to be plundered by the Romans. Like the previous battle at Ad Decimum, it is again notable that Belisarius failed to keep his forces together, and was forced to fight with a considerable numerical disadvantage. The dispersal of his army after the battle, looting heedlessly and leaving themselves vulnerable to a potential Vandal counter-attack, was also an indication of the poor discipline in the Roman army and the command difficulties Belisarius faced. As Bury comments, the expedition's fate might have been quite different "if Belisarius had been opposed to a commander of some ability and experience in warfare", and points out that Procopius himself "expresses amazement at the issue of the war, and does not hesitate to regard it not as a feat of superior strategy but as a paradox of fortune".Bury (1923), Vol. II, p. 137

A Roman detachment under John the Armenian pursued the fleeing Vandal king for five days and nights, and was almost upon him when he was killed in an accident. The Romans halted to mourn their leader, allowing Gelimer to escape, first to Hippo Regius

Hippo Regius (also known as Hippo or Hippone) is the ancient name of the modern city of Annaba, Algeria. It historically served as an important city for the Phoenicians, Berbers, Romans, and Vandals. Hippo was the capital city of the Vandal Kin ...

and from there to the city of Medeus on Mount Papua, on whose Mauri inhabitants he could rely. Belisarius sent 400 men under the Herul Pharas to blockade him there.Bury (1923), Vol. II, p. 138Hughes (2009), p. 106 Belisarius himself made for Hippo Regius, where the Vandals, who had fled to various sanctuaries, surrendered to the Roman general, who promised that they would be well treated and sent to Constantinople in spring. Belisarius was also fortunate in recovering the Vandal royal treasure, which had been loaded on a ship at Hippo. Bonifatius, Gelimer's secretary, was supposed to sail with it to Spain, where Gelimer too would later follow, but adverse winds kept the ship in harbour and in the end, Bonifatius handed it over to the Romans in exchange for his own safety (as well as a considerable share of the treasure, if Procopius is to be believed). Belisarius also began to extend his authority over the more distant provinces and outposts of the Vandal kingdom: Cyril was dispatched to Sardinia and Corsica with Tzazon's head as proof of his victory, John was sent to Caesarea

Caesarea () ( he, קֵיסָרְיָה, ), ''Keysariya'' or ''Qesarya'', often simplified to Keisarya, and Qaysaria, is an affluent town in north-central Israel, which inherits its name and much of its territory from the ancient city of Caesar ...

on the coast of Mauretania Caesariensis, another John was sent to the twin fortresses of Septem and Gadira, which controlled the Straits of Gibraltar, and Apollinarius to take possession of the Balearic Islands. Aid was also sent to the provincials in Tripolitania, who had been subject to attacks by the local Mauri tribes.Hughes (2009), p. 107 Belisarius also demanded the return of the port of Lilybaeum

Marsala (, local ; la, Lilybaeum) is an Italian town located in the Province of Trapani in the westernmost part of Sicily. Marsala is the most populated town in its province and the fifth in Sicily.

The town is famous for the docking of Gius ...

in western Sicily from the Ostrogoths, who had captured it during the war, as it too had been part of the Vandal kingdom. An exchange of letters followed between Justinian and the Ostrogoth court, through which Justinian was drawn into the intrigues of the latter, leading to the Roman invasion of Italy a year later.

Meanwhile, Gelimer remained blockaded by Pharas at the mountain stronghold of Medeus, but, as the blockade dragged through the winter, Pharas grew impatient. He attacked the mountain stronghold, only to be beaten back with the loss of a quarter of his men. While a success for Gelimer, it did not alter his hopeless situation, as he and his followers remained tightly blockaded and began to suffer from lack of food. Pharas sent him messages calling upon him to surrender and spare his followers the misery, but it was not until March that the Vandal king agreed to surrender after receiving guarantees for his safety. Gelimer was then escorted to Carthage.

Aftermath

Belisarius' triumph

Belisarius would not remain long in Africa to consolidate his success, as a number of officers in his army, in hopes of their own advancement, sent messengers to Justinian claiming that Belisarius intended to establish his own kingdom in Africa. Justinian then gave his general two choices as a test of his intentions: he could return to Constantinople or remain in Africa. Belisarius, who had captured one of the messengers and was aware of the slanders against him, chose to return. He left Africa in the summer, accompanied by Gelimer, large numbers of captured Vandals—who were enrolled in five regiments of the ''Vandali Iustiniani'' ("Vandals of Justinian") by the emperor—and the Vandal treasure, which included many objects looted from Rome 80 years earlier, including the imperial regalia and the menorah of the

Belisarius would not remain long in Africa to consolidate his success, as a number of officers in his army, in hopes of their own advancement, sent messengers to Justinian claiming that Belisarius intended to establish his own kingdom in Africa. Justinian then gave his general two choices as a test of his intentions: he could return to Constantinople or remain in Africa. Belisarius, who had captured one of the messengers and was aware of the slanders against him, chose to return. He left Africa in the summer, accompanied by Gelimer, large numbers of captured Vandals—who were enrolled in five regiments of the ''Vandali Iustiniani'' ("Vandals of Justinian") by the emperor—and the Vandal treasure, which included many objects looted from Rome 80 years earlier, including the imperial regalia and the menorah of the Second Temple

The Second Temple (, , ), later known as Herod's Temple, was the reconstructed Temple in Jerusalem between and 70 CE. It replaced Solomon's Temple, which had been built at the same location in the United Kingdom of Israel before being inherited ...

.Bury (1923), Vol. II, p. 139 In Constantinople, Belisarius was given the honour of celebrating a triumph—the first to be celebrated in Constantinople since its foundation and the first granted to a private citizen in over five and a half centuries—and described by Procopius:

Gelimer was given an ample estate in Galatia

Galatia (; grc, Γαλατία, ''Galatía'', "Gaul") was an ancient area in the highlands of central Anatolia, roughly corresponding to the provinces of Ankara and Eskişehir, in modern Turkey. Galatia was named after the Gauls from Thrace ...

, and would have been raised to patrician rank if he had not steadfastly refused to renounce his Arian faith. Belisarius was also named ''consul ordinarius'' for the year 535, allowing him to celebrate a second triumphal procession, being carried through the streets seated on his consular curule chair

A curule seat is a design of a (usually) foldable and transportable chair noted for its uses in Ancient Rome and Europe through to the 20th century. Its status in early Rome as a symbol of political or military power carried over to other civilizat ...

, held aloft by Vandal warriors, distributing largesse to the populace from his share of the war booty.

Re-establishment of Roman rule in Africa and the Mauri Wars

Immediately after Tricamarum, Justinian hastened to proclaim the recovery of Africa:

The emperor was determined to restore the province to its former extent and prosperity—indeed, in the words of J.B. Bury, he intended "to wipe out all traces of the Vandal conquest, as if it had never been, and to restore the conditions which had existed before the coming of Geiseric". To this end, the Vandals were barred from holding office or even property, which was returned to its former owners; most Vandal males became slaves, while the victorious Roman soldiers took their wives; and the Chalcedonian Church was restored to its former position while the Arian Church was dispossessed and persecuted. As a result of these measures, the Vandal population was diminished and emasculated. It gradually disappeared entirely, becoming absorbed into the broader provincial population. Already in April 534, before the surrender of Gelimer, the old Roman provincial division along with the full apparatus of Roman administration was restored, under a praetorian prefect rather than under a

Immediately after Tricamarum, Justinian hastened to proclaim the recovery of Africa:

The emperor was determined to restore the province to its former extent and prosperity—indeed, in the words of J.B. Bury, he intended "to wipe out all traces of the Vandal conquest, as if it had never been, and to restore the conditions which had existed before the coming of Geiseric". To this end, the Vandals were barred from holding office or even property, which was returned to its former owners; most Vandal males became slaves, while the victorious Roman soldiers took their wives; and the Chalcedonian Church was restored to its former position while the Arian Church was dispossessed and persecuted. As a result of these measures, the Vandal population was diminished and emasculated. It gradually disappeared entirely, becoming absorbed into the broader provincial population. Already in April 534, before the surrender of Gelimer, the old Roman provincial division along with the full apparatus of Roman administration was restored, under a praetorian prefect rather than under a diocesan

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associate ...

''vicarius

''Vicarius'' is a Latin word, meaning ''substitute'' or ''deputy''. It is the root of the English word "vicar".

History

Originally, in ancient Rome, this office was equivalent to the later English " vice-" (as in "deputy"), used as part of th ...

'', since the original parent prefecture of Africa, Italy, was still under Ostrogothic rule. The army of Belisarius was left behind to form the garrison of the new prefecture, under the overall command of a ''magister militum

(Latin for "master of soldiers", plural ) was a top-level military command used in the later Roman Empire, dating from the reign of Constantine the Great. The term referred to the senior military officer (equivalent to a war theatre commander, ...

'' and several regional '' duces''. Almost from the start, an extensive fortification programme was also initiated, including the construction of city walls as well as smaller forts to protect the countryside, whose remnants are still among the most prominent archaeological remains in the region.

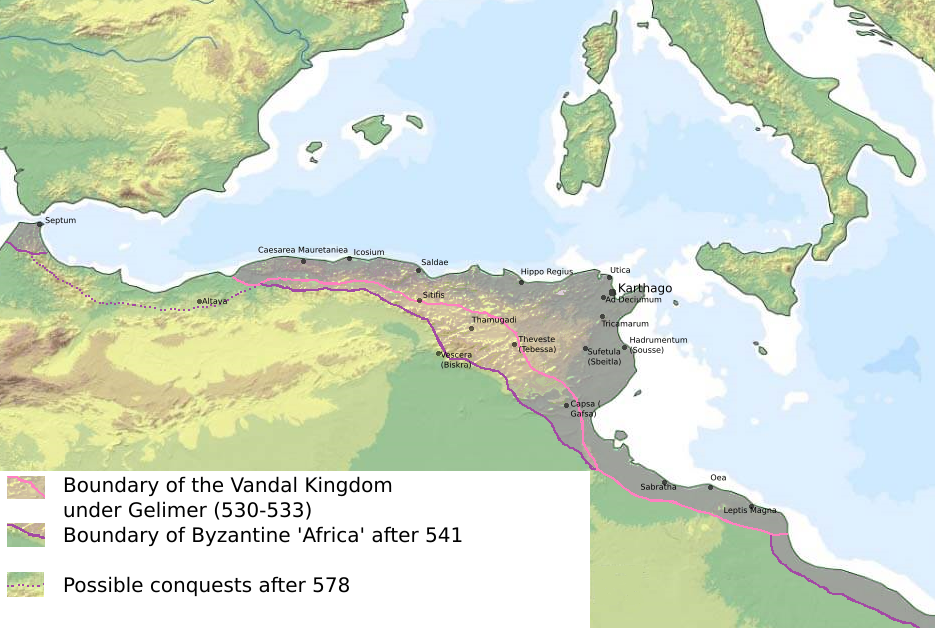

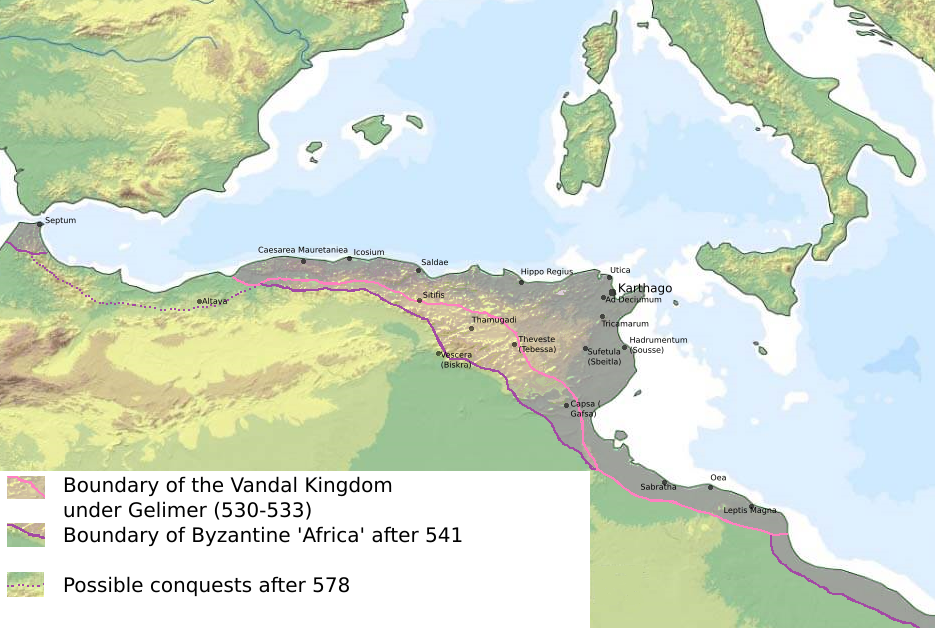

Despite Justinian's intentions and proclamations, however, Roman control over Africa was not yet secure. During his campaign, Belisarius had secured most of the provinces of Byzacena, Zeugitana and Tripolitania. Further west, on the other hand, imperial control extended in a series of strongholds captured by the fleet along the coast as far as Constantine, while most of the inland areas of Numidia and Mauretania remained under the control of the local Mauri tribes, as indeed had been the case under the Vandal kings. The Mauri initially acknowledged the Emperor's suzerainty and gave hostages to the imperial authorities, but they soon became restive and rose in revolt. The first imperial governor, Belisarius' former ''domesticus'' Solomon, who combined the offices of both ''magister militum'' and praetorian prefect, was able to score successes against them and strengthen Roman rule in Africa, but his work was interrupted by a widespread military mutiny in 536. The mutiny was eventually subdued by Germanus, a cousin of Justinian, and Solomon returned in 539. He fell, however, in the Battle of Cillium in 544 against the united Mauri tribes, and Roman Africa was again in jeopardy. It would not be until 548 that the resistance of the Mauri tribes would be finally broken by the talented general John Troglita.Diehl (1896), pp. 41–93, 333–381

References

Sources

Primary

*Secondary

* * * * *{{cite book, last1=Merrils, first1=Andy, last2=Miles, first2=Richard, title=The Vandals, publisher=Wiley-Blackwell, location=Chichester, U.K.; Malden, MA, year=2010, isbn=978-1-405-16068-1 530s conflicts 533 534 6th century in Africa 6th-century conflicts Military history of Algeria Military history of Libya Military history of Tunisia