Vélodrome d'hiver on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Vélodrome d'Hiver (, ''Winter Velodrome''), colloquially Vel' d'Hiv', was an indoor bicycle racing cycle track and stadium (

velodrome

A velodrome is an arena for track cycling. Modern velodromes feature steeply banked oval tracks, consisting of two 180-degree circular bends connected by two straights. The straights transition to the circular turn through a moderate easement ...

) on rue Nélaton, not far from the Eiffel Tower

The Eiffel Tower ( ; french: links=yes, tour Eiffel ) is a wrought-iron lattice tower on the Champ de Mars in Paris, France. It is named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built the tower.

Locally nicknamed ...

in Paris. As well as a cycling track, it was used for ice hockey

Ice hockey (or simply hockey) is a team sport played on ice skates, usually on an ice skating rink with lines and markings specific to the sport. It belongs to a family of sports called hockey. In ice hockey, two opposing teams use ice ...

, basketball

Basketball is a team sport in which two teams, most commonly of five players each, opposing one another on a rectangular Basketball court, court, compete with the primary objective of #Shooting, shooting a basketball (ball), basketball (appr ...

, wrestling

Wrestling is a series of combat sports involving grappling-type techniques such as clinch fighting, throws and takedowns, joint locks, pins and other grappling holds. Wrestling techniques have been incorporated into martial arts, combat s ...

, boxing

Boxing (also known as "Western boxing" or "pugilism") is a combat sport in which two people, usually wearing protective gloves and other protective equipment such as hand wraps and mouthguards, throw punches at each other for a predetermined ...

, roller-skating, circus

A circus is a company of performers who put on diverse entertainment shows that may include clowns, acrobats, trained animals, trapeze acts, musicians, dancers, hoopers, tightrope walkers, jugglers, magicians, ventriloquists, and unicyclis ...

es, bullfighting, spectaculars, and demonstrations. It was the first permanent indoor track in France and the name persisted for other indoor tracks built subsequently.

In July 1942, French police, acting under orders from the German authorities in Occupied Paris, used the velodrome to hold thousands of Jews and others who were victims in a mass arrest

A mass arrest occurs when police apprehend large numbers of suspects at once. This sometimes occurs at protests. Some mass arrests are also used in an effort to combat gang activity. This is sometimes controversial, and lawsuits sometimes result. I ...

. The Jews were held at the velodrome before they were moved to a concentration camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

in the Parisian suburbs at Drancy

Drancy () is a commune in the northeastern suburbs of Paris in the Seine-Saint-Denis department in northern France. It is located 10.8 km (6.7 mi) from the center of Paris.

History

Toponymy

The name Drancy comes from Medieval La ...

and then to the extermination camp at Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 Nazi concentration camps, concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, occupied Poland (in a portion annexed int ...

. The incident became known as the " Vel' d'Hiv' Roundup" (''Rafle du Vel' d'Hiv).

Origins

The original track was housed in the Salles des Machines, the building used for the industrial display of the World's Fair, which ended in 1900. The building was unoccupied after the exhibition. In 1902, the Salle des Machines was inspected byHenri Desgrange

Henri Desgrange (31 January 1865 – 16 August 1940) was a French bicycle racer and sports journalist. He set twelve world track cycling records, including the hour record of on 11 May 1893. He was the first organiser of the Tour de France.

...

, who the following year inaugurated the Tour de France

The Tour de France () is an annual men's multiple-stage bicycle race primarily held in France, while also occasionally passing through nearby countries. Like the other Grand Tours (the Giro d'Italia and the Vuelta a España), it consists ...

on behalf of the newspaper that he edited, '' L'Auto''. With him were Victor Goddet, the newspaper's treasurer, an engineer named Durand, and an architect, Gaston Lambert. It was Lambert who said he could turn the hall into a sports arena with a track 333 metres long and eight metres wide.Grunwald, Liliane, and Claude Cattaert, ''Le Vel' d'Hiv '': 1903–1959'' (Paris: Éditions Ramsay, 1979), . He finished it in 20 days.

The first meeting there, on 20 December 1903, had an audience of 20,000. They paid seven francs for the best view and a single franc to see hardly anything at all. The seating was primitive and there was no heating. The first event was not a cycle race but a walking competition over 250 metres. The first cycling competition was a race ridden behind pacing motorcycles

A motorcycle (motorbike, bike, or trike (if three-wheeled)) is a two or three-wheeled motor vehicle steered by a handlebar. Motorcycle design varies greatly to suit a range of different purposes: long-distance travel, commuting, cruising ...

. Only one rider—Cissac—managed to complete the , the others having crashed on the unaccustomed steepness of the track banking.

Change of name and track

In 1909 the Salle des Machines was listed for demolition to improve the view of the Eiffel Tower. Desgrange moved to another building nearby, at the corner of the boulevard de Grenelle and the rue Nélaton. The venue was named the Vélodrome d'Hiver. The new track, also designed by Lambert, was 253.16 m round at the base but exactly 250 m on the line ridden by the motor-paced riders (considered the stars of the day). Lambert built two tiers of seats, which towered above bankings so steep for their day that they were considered cliff-like. In the track centre, Lambert built a roller-skating rink of 2,700 square metres. He lit the whole lot with 1,253 hanging lamps. There could be so many spectators jammed in the track centre for cycling events that they resembled passengers in the Paris métro in the rush hour.Chany, Pierre (1988) ''La Fabuleuse Histoire du Cyclisme'', Nathan, France The richer and more knowledgeable spectators bought track-side seats and the rest crowded into the upper balcony from which the track looked a distant bowl. A rivalry grew between those in the top row and those below them, to the extent that those on high sometimes threw sausages, bread rolls and even bottles onto those below or, if they could throw that far, onto the track. The hall's managers had to install a net to catch the larger missiles.Six-days

Six-day cycle racing had started in London in the 19th century but became truly popular after changing to a race not for individuals but for teams of two. Created atMadison Square Garden

Madison Square Garden, colloquially known as The Garden or by its initials MSG, is a multi-purpose indoor arena in New York City. It is located in Midtown Manhattan between Seventh and Eighth avenues from 31st to 33rd Street, above Pennsylv ...

(after New York prohibited . it became known in English as the madison Madison may refer to:

People

* Madison (name), a given name and a surname

* James Madison (1751–1836), fourth president of the United States

Place names

* Madison, Wisconsin, the state capital of Wisconsin and the largest city known by this ...

and in French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

as ''l'américaine''. The first such six-day race at the Vel' d'Hiv' started on 13 January 1913.

The riders included the Tour de France

The Tour de France () is an annual men's multiple-stage bicycle race primarily held in France, while also occasionally passing through nearby countries. Like the other Grand Tours (the Giro d'Italia and the Vuelta a España), it consists ...

winners Louis Trousselier

Louis Trousselier (; 1881 – 24 April 1939) was a French racing cyclist who won the 1905 Tour de France. His other major wins were Paris–Roubaix, also in 1905, and the 1908 Bordeaux–Paris. He came third in the 1906 Tour de France and won 13 ...

and Octave Lapize

Octave Lapize (; 24 October 1887 – 14 July 1917) was a French professional road racing cyclist and track cyclist.

Most famous for winning the 1910 Tour de France and a bronze medal at the 1908 Summer Olympics in the men's 100 kilometres, h ...

and other prominent riders such as Émile Georget

Émile Georget (21 September 1881 – 16 October 1960) was a French road racing cyclist. Born in Bossay-sur-Claise, he was the younger brother of cyclist Léon Georget. He died at Châtellerault.

Career achievements

Tour de France

Georget s ...

. The race began at 6 pm and by 9 pm all 20,000 seats were sold. Among those who watched was the millionaire Henri de Rothschild

Rothschild () is a name derived from the German ''zum rothen Schild'' (with the old spelling "th"), meaning "with the red sign", in reference to the houses where these family members lived or had lived. At the time, houses were designated by sign ...

, who offered a prize of 600 Fr, and the dancer Mistinguett, who offered 100 Fr. The winners were Goulet and Fogler, an American-Australian pairing.

The Franco-American writer René de Latour

René de Latour (born New York, United States, 30 September 1906, died Quiberon, France, 4 September 1986) was a Franco-American sports journalist, race director of the Tour de l'Avenir cycle race, and correspondent of the British magazine, ''Sp ...

said: "I have known the time when it was considered quite a feat to get into the Vel' d'Hiv' during a six-day race. There were mounted police all round the block, barriers were erected some way from the building, and if you did not have a ticket or a pass to show, you were not allowed anywhere near the place. You can guess that the disappointed fans often produced a near-riot."

A tradition started in 1926 of electing a Queen of the Six, whose job included starting the race. Among them were Édith Piaf

Édith Piaf (, , ; born Édith Giovanna Gassion, ; December 19, 1915– October 10, 1963) was a French singer, lyricist and actress. Noted as France's national chanteuse, she was one of the country's most widely known international stars.

Pi ...

, Annie Cordy

Léonie Juliana, Baroness Cooreman (16 June 1928 – 4 September 2020), also known by her stage name Annie Cordy, was a Belgian actress and singer. She appeared in more than 50 films from 1954 and staged many memorable appearances at Bruno Coq ...

and the accordionist Yvette Horner, who also played from the roof of a car while preceding the Tour de France

The Tour de France () is an annual men's multiple-stage bicycle race primarily held in France, while also occasionally passing through nearby countries. Like the other Grand Tours (the Giro d'Italia and the Vuelta a España), it consists ...

.

Races at the Vel' d'Hiv' were sometimes doubted for their genuineness. While the spectacle drew large and even capacity crowds, the best riders were rumoured to control the race. The French journalist Pierre Chany

Pierre Chany (16 December 1922 – 18 June 1996) was a French cycling journalist. He covered the Tour de France 49 times and was for a long time the main cycling writer for the daily newspaper, ''L'Équipe''.

Biography

Chany was born in La ...

wrote:

:There was a lot of talk about the relative honesty of the results, and journalists sometimes asked themselves what importance they ought to place on victories in these six-day races. The best of the field combined between themselves, it was known, to fight against other teams and to get their own hands on the biggest prizes, which they then shared between them. This coalition, cruelly nicknamed the Blue Train fter a luxury rail service patronised by the richimposed its rule and sometimes even the times of the race, the length of the rest periods. The little teams fought back on certain days but, generally, the law belonged to the cracks, better equipped physically and often better organised.

1924 Summer Olympics

For the1924 Summer Olympics

The 1924 Summer Olympics (french: Jeux olympiques d'été de 1924), officially the Games of the VIII Olympiad (french: Jeux de la VIIIe olympiade) and also known as Paris 1924, were an international multi-sport event held in Paris, France. The o ...

, the velodrome hosted boxing

Boxing (also known as "Western boxing" or "pugilism") is a combat sport in which two people, usually wearing protective gloves and other protective equipment such as hand wraps and mouthguards, throw punches at each other for a predetermined ...

, fencing

Fencing is a group of three related combat sports. The three disciplines in modern fencing are the foil, the épée, and the sabre (also ''saber''); winning points are made through the weapon's contact with an opponent. A fourth discipline, ...

, weightlifting

Weightlifting generally refers to activities in which people lift weights, often in the form of dumbbells or barbells. People lift various kinds of weights for a variety of different reasons. These may include various types of competition; pro ...

, and wrestling

Wrestling is a series of combat sports involving grappling-type techniques such as clinch fighting, throws and takedowns, joint locks, pins and other grappling holds. Wrestling techniques have been incorporated into martial arts, combat s ...

events.

Ernest Hemingway

The American writerErnest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. His economical and understated style—which he termed the iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century f ...

was a regular fan of six-day and other races at the Vel' d'Hiv' while he lived in Paris. He wrote:

:I have started many stories about bicycle racing but have never written one that is as good as the races are both on the indoor and outdoor tracks and on the roads. But I will get the Vélodrome d’Hiver with the smoky light of the afternoon and the high-banked wooden track and the whirring sound the tires made on the wood as the riders passed, the effort and the tactics as the riders climbed and plunged, each one a part of his machine. ... I must write the strange world of the six-day races and the marvels of the road-racing in the mountains. French is the only language it has ever been written in properly and the terms are all French and that is what makes it hard to write.

Boxing

Boxing

Boxing (also known as "Western boxing" or "pugilism") is a combat sport in which two people, usually wearing protective gloves and other protective equipment such as hand wraps and mouthguards, throw punches at each other for a predetermined ...

began at the Vel' d'Hiv' after a meeting between an American, Jeff Dickson, and Henri Desgrange, the track's main owner and leading promoter. Dickson arrived in France from Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

in 1917 as a "sammie". Sammies, named after the owner of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc., also known as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures and abbreviated as MGM, is an American film, television production, distribution and media company owned by amazon (company), Amazon through MGM Holdings, founded o ...

, were cameramen sent from the U.S. to film American soldiers in World War I.

Dickson stayed on in France after the war and began promoting boxing in the Wagram

Deutsch-Wagram (literally "German Wagram", ), often shortened to Wagram, is a village in the Gänserndorf District, in the state of Lower Austria, Austria. It is in the Marchfeld Basin, close to the Vienna city limits, about 15 km (9 mi) northe ...

area of Paris. He and Desgrange got on and the two agreed he should organise a first boxing tournament at the Vel' d'Hiv' in 1929. The main match pitted Milou Pladner against Frankie Genaro

Frank "Frankie" Genaro (born DiGennaro, August 26, 1901 – December 27, 1966) was an American former Olympic gold medalist and a 1928 National Boxing Association (NBA) World flyweight Champion. He is credited with engaging in 130 bouts, recordi ...

, bringing in 920,110Fr.

The Lion Hunt and other spectacles

Dickson joined the management of the Vel' d'Hiv'. In 1931 he renovated the building to allow other uses in the centre of the cycling track: he removed several pillars that blocked the view of some spectators, took up the roller-skating rink, laid anice rink

An ice rink (or ice skating rink) is a frozen body of water and/or an artificial sheet of ice created using hardened chemicals where people can ice skate or play winter sports. Ice rinks are also used for exhibitions, contests and ice shows. The ...

of 60 m by 30 m, and constructed a cover for the rink to allow its use for other activities. The building was rechristened the “Palais des Sports de Grenelle”, though its former name remained in use.Tristan Alric, “Un siècle de hockey en France”, p. 23 Under Dickson, the Vel' d'Hiv' became home to the Français Volants ice hockey

Ice hockey (or simply hockey) is a team sport played on ice skates, usually on an ice skating rink with lines and markings specific to the sport. It belongs to a family of sports called hockey. In ice hockey, two opposing teams use ice ...

team. The rink also featured skating shows by Sonja Henie

Sonja Henie (8 April 1912 – 12 October 1969) was a Norwegian figure skater and film star. She was a three-time Olympic champion (1928, 1932, 1936) in women's singles, a ten-time World champion (1927–1936) and a six-time European champio ...

in 1953 and 1955 and Holiday on Ice

Holiday on Ice is an ice show currently owned by Medusa Music Group GmbH, a subsidiary of CTS EVENTIM, Europe's largest ticket distributor, with its headquarters in Bremen, Germany.

History

Holiday on Ice originated in the United States in Decem ...

(1950 to 1958).

His most spectacular venture was his greatest and most expensive flop. Dickson discovered from the newspaper '' Paris-Midi'' that the Schneider circus

A circus is a company of performers who put on diverse entertainment shows that may include clowns, acrobats, trained animals, trapeze acts, musicians, dancers, hoopers, tightrope walkers, jugglers, magicians, ventriloquists, and unicyclis ...

in Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

was auctioning 100 lions. Dickson bought the animals the same day, along with their cages and trailers, for 80,000 Fr. He constructed a stage set, acquired two sick camels abandoned by a circus at Maisons-Alfort, hired fire-eaters and employed 20 actors to dress as African explorers—all to stage a spectacle called The Lion Hunt.

The lions, however, arrived from Naples feeling tired and limp. Dickson assured reporters they needed only a meal and began importing dead animals from local abattoirs. Things didn't improve. On the first night of the show, all 100 lions were released into the arena but showed no signs of excitement, much less ferocity. Dickson ordered his "explorers" to fire into the air to wake them up. The air became bitter with cordite fumes but the lions did little more than stroll about and urinate on the scenery. Now convinced the animals were harmless, stagehands began beating them, at which children began to cry and parents shouted angry protests. The organizers withdrew the animals and moved to the next act of the show. Things went little better. The camels refused to walk in a line as in a desert caravan. And their attendants, who were unemployed black people recruited from the streets, stumbled in the sand under their unaccustomed stage clothing. The show's run was abandoned.

Dickson now had two camels and 100 lions that he no longer needed. An assistant tied the camels behind a car, led them to the Seine

)

, mouth_location = Le Havre/ Honfleur

, mouth_coordinates =

, mouth_elevation =

, progression =

, river_system = Seine basin

, basin_size =

, tributaries_left = Yonne, Loing, Eure, Risle

, tributa ...

and abandoned them. There they were found by the police. Eventually Dickson rented the camels and lions to another circus for 10,000 Fr a week, only for the circus to fail and Dickson to be summoned to collect his animals. By now he was also being pursued by the for cruelty in abandoning the camels. The animals were finally sent to a zoo

A zoo (short for zoological garden; also called an animal park or menagerie) is a facility in which animals are kept within enclosures for public exhibition and often bred for conservation purposes.

The term ''zoological garden'' refers to z ...

near Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; nds, label=Hamburg German, Low Saxon, Hamborg ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg (german: Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg; nds, label=Low Saxon, Friee un Hansestadt Hamborg),. is the List of cities in Germany by popul ...

.

The venture ended with the loss of 700,000 Fr by the Vel' d'Hiv'.

Dickson returned to America in 1939 and died when his bomber

A bomber is a military combat aircraft designed to attack ground and naval targets by dropping air-to-ground weaponry (such as bombs), launching torpedoes, or deploying air-launched cruise missiles. The first use of bombs dropped from an air ...

was shot down at St-André-de-l'Eure on 14 July, France's national day, in 1943. He is buried in the American cemetery at Omaha Beach

Omaha Beach was one of five beach landing sectors designated for the amphibious assault component of operation Overlord during the Second World War. On June 6, 1944, the Allies invaded German-occupied France with the Normandy landings. "Omaha" r ...

west of Caen

Caen (, ; nrf, Kaem) is a commune in northwestern France. It is the prefecture of the department of Calvados. The city proper has 105,512 inhabitants (), while its functional urban area has 470,000,Goddet, Jacques (1991) ''L'Équipée Belle'', Robert Laffont, France

Needing a place to hold the detainees, the Germans demanded the keys of the Vel' d'Hiv' from its owner, Jacques Goddet, who had taken over from his father Victor and from Henri Desgrange. The circumstances in which Goddet surrendered the keys remain a mystery, and the episode occupies only a few lines in his autobiography.

The Vel' d'Hiv' had a glass roof, which had been painted dark blue to help avoid attracting bomber navigators. The dark glass roof, combined with windows screwed shut for security, raised the temperature inside the structure. The 13,152 people held there had no lavatories; of the 10 available, five were sealed because their windows offered a way out, and the others were blocked. The arrested Jews were kept there for five days with only water and food brought by

Needing a place to hold the detainees, the Germans demanded the keys of the Vel' d'Hiv' from its owner, Jacques Goddet, who had taken over from his father Victor and from Henri Desgrange. The circumstances in which Goddet surrendered the keys remain a mystery, and the episode occupies only a few lines in his autobiography.

The Vel' d'Hiv' had a glass roof, which had been painted dark blue to help avoid attracting bomber navigators. The dark glass roof, combined with windows screwed shut for security, raised the temperature inside the structure. The 13,152 people held there had no lavatories; of the 10 available, five were sealed because their windows offered a way out, and the others were blocked. The arrested Jews were kept there for five days with only water and food brought by

Other spectacles

* '' Naissance d'une cité'' was organised byJean-Richard Bloch

Jean-Richard Bloch (25 May 1884 – 15 March 1947) was a French people, French critic, novelist and playwright.

He was a member of the French Communist Party (PCF) and worked with Louis Aragon in the evening daily ''Ce soir''.

Early life

Bloc ...

on 18 October 1937 as part of the Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne

The ''Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne'' (International Exposition of Art and Technology in Modern Life) was held from 25 May to 25 November 1937 in Paris, France. Both the Palais de Chaillot, housing the M ...

.

*The Vélodrome d'Hiver was also the venue of the 1951

Events

January

* January 4 – Korean War: Third Battle of Seoul – Chinese and North Korean forces capture Seoul for the second time (having lost the Second Battle of Seoul in September 1950).

* January 9 – The Government of the United ...

European basketball championship

EuroBasket, also commonly referred to as the European Basketball Championship, is the main international basketball competition that is contested quadrennially, by the senior men's national teams that are governed by FIBA Europe, which is the E ...

.

Vel' d'Hiv' Roundup

The Vel' d'Hiv' was available for hire to whoever wanted it. Among those who booked wasJacques Doriot

Jacques Doriot (; 26 September 1898 – 22 February 1945) was a French politician, initially communist, later fascist, before and during World War II.

In 1936, after his exclusion from the Communist Party, he founded the French Popular Party (P ...

, who led France's largest fascist

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

party, the PPF. It was at the Vel' d'Hiv', among other venues, that Doriot, with his Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

-like salute, roused crowds to join his cause.

In 1940, the Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

invaded France and occupied its northern half, including Paris. On 7 June 1942, they completed plans for ("Operation Spring Breeze") to arrest 28,000 Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

using 9,000 French policemen. Arrests started early on 16 July and were complete by the next day. Among those who helped in the round-up were 3,400 young members of Doriot's PPF.

Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abili ...

, the Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

and the few doctors and nurses allowed to enter.

Those arrested were sent to an internment camp in half-completed tower blocks at Drancy

Drancy () is a commune in the northeastern suburbs of Paris in the Seine-Saint-Denis department in northern France. It is located 10.8 km (6.7 mi) from the center of Paris.

History

Toponymy

The name Drancy comes from Medieval La ...

and then to the extermination camp at Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 Nazi concentration camps, concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany, occupied Poland (in a portion annexed int ...

. Only 400 survived.

Post-war track encounter

An enthusiast, John Aulton, described the track in the first years after the war. He visited Paris on a tour organised for English schoolchildren who slept in tents in the grounds of alycée

In France, secondary education is in two stages:

* ''Collèges'' () cater for the first four years of secondary education from the ages of 11 to 15.

* ''Lycées'' () provide a three-year course of further secondary education for children between ...

. He was alone in wanting to see the Vélodrome d'Hiver. He wrote::I set out on my Raleigh Sports.... I arrived elated and full of anticipation but my joy was short-lived, all the doors were locked and barred and there was no sign of life. Without warning a side door flew open and a small powerfully built man came hurtling out of the gloom into the sunlight. A flapping empty sleeve hung where his right arm should have been. He poured a tirade of French at me before stepping back inside and slamming the door. I gave the door another swift kick and shouted in English that all I wanted was to see the famous track. The door slowly opened and the one-armed man stepped outside, but this time a broad smile covered his previously angry face. "''Anglais?''" he said, as if uttering some special password. He spoke in halting English. Did I knowWembley Wembley () is a large suburbIn British English, "suburb" often refers to the secondary urban centres of a city. Wembley is not a suburb in the American sense, i.e. a single-family residential area outside of the city itself. in north-west Londo ...? He had ridden the London six-day there? He put his one good arm around my shoulder and escorted me and my Raleigh into the stadium. :The old track was looking the worse for wear. There was dust everywhere and the shafts of sunlight that penetrated the dirty blue skylights picked out the particles dancing in the air. I walked over to the banking and touched the boards that had seen so much drama. Suddenly and without explanation a feeling of fear and revulsion came over me; I grabbed my bike and ran as fast as I could into the outside world. The door would not open at first but a panic-stricken tug freed it and I dashed out into the heat of a Parisian afternoon and pedalled away not caring in which direction just so long as I could get away from the Vélodrome d'Hiver.

The final events

The last six-day race at the Vel' d'Hiv' started on 7 November 1958. The stars wereRoger Rivière

Roger Rivière (23 February 1936, Saint-Étienne – 1 April 1976, Saint-Galmier) was a French track and road bicycle racer. He raced as a professional from 1957 to 1960.

Rivière, a time trialist, all-around talent on the road, and a three-ti ...

, Jacques Anquetil

Jacques Anquetil (; 8 January 1934 – 18 November 1987) was a French road racing cyclist and the first cyclist to win the Tour de France five times, in 1957 and from 1961 to 1964.

He stated before the 1961 Tour that he would gain the ...

, Fausto Coppi

Angelo Fausto Coppi (; 15 September 1919 – 2 January 1960) was an Italian cyclist, the dominant international cyclist of the years after the Second World War. His successes earned him the title ''Il Campionissimo'' ("Champion of Champions ...

and André Darrigade

André Darrigade (born 24 April 1929 in Narrosse) is a retired French professional road bicycle racer between 1951 and 1966. Darrigade, a road sprinter won the 1959 World Championship and 22 stages of the Tour de France. Five of those Tour vict ...

. The race was run with teams of three. Rivière had to drop out after a crash with Anquetil in the first hours; on 12 November, Darrigade won the biggest prime, or intermediate prize, ever offered at the track: one million francs. The overall winners were Anquetil and his partners, Darrigade and Terruzzi. The building had grown old, dirty and dusty and leaked when it rained. Electricity cables hung in loops.

The final night at the Vel' d'Hiv' was 12 May 1959, featuring the painter Salvador Dalí

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, Marquess of Dalí of Púbol (; ; ; 11 May 190423 January 1989) was a Spanish Surrealism, surrealist artist renowned for his technical skill, precise draftsmanship, and the striking and bizarr ...

. Among his stage props was a model of the Eiffel Tower, which he exploded to symbolise the end of the exhibition hall in which he stood. A fire destroyed part of the Vélodrome d'Hiver in 1959 and the rest of the structure was demolished. A block of flats and a building belonging to the Ministry of the Interior now stand on the site.

Government apology

For decades the French government declined to apologize for the role of French policemen in the round-up or for any other state complicity. It was argued (by de Gaulle and others) that theFrench Republic

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

had been dismantled when Philippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Pétain (24 April 1856 – 23 July 1951), commonly known as Philippe Pétain (, ) or Marshal Pétain (french: Maréchal Pétain), was a French general who attained the position of Marshal of France at the end of Worl ...

instituted a new French State during the war and that the Republic had been re-established after the war had ended. It was not for the Republic, therefore, to apologise for events that happened while it had not existed and which had been carried out by a state which it did not recognise. For example, former President François Mitterrand

François Marie Adrien Maurice Mitterrand (26 October 19168 January 1996) was President of France, serving under that position from 1981 to 1995, the longest time in office in the history of France. As First Secretary of the Socialist Party, he ...

had maintained this position. The claim was more recently reiterated by Marine Le Pen

Marion Anne Perrine "Marine" Le Pen (; born 5 August 1968) is a French lawyer and politician who ran for the French presidency in 2012, 2017, and 2022. A member of the National Rally (RN; previously the National Front, FN), she served as its ...

, leader of the National Front Party, during the 2017 election campaign.

On 16 July 1995, President Jacques Chirac

Jacques René Chirac (, , ; 29 November 193226 September 2019) was a Politics of France, French politician who served as President of France from 1995 to 2007. Chirac was previously Prime Minister of France from 1974 to 1976 and from 1986 to ...

stated that it was time that France faced up to its past and he acknowledged the role that the state had played in the persecution of Jews and other victims of the German occupation. Those responsible for the round-up, according to Chirac, were "" ("450 policemen and gendarmes, French, under the authority of their leaders hoobeyed the demands of the Nazis").

To mark the 70th anniversary of the round-up, President François Hollande

François Gérard Georges Nicolas Hollande (; born 12 August 1954) is a French politician who served as President of France from 2012 to 2017. He previously was First Secretary of the Socialist Party (France), First Secretary of the Socialist P ...

gave a speech at a monument of the Vel' d'Hiv' round-up on 22 July 2012. The president recognized that this event was a crime committed "in France, by France," and emphasized that the deportations in which French police participated were offences committed against French values, principles, and ideals. He continued his speech by remarking that the Republic would clamp down on anti-Semitism "with the greatest determination".

The first official admission that the French State had been complicit in the deportation of 76,000 Jews during WW II was made in 1995 by President Jacques Chirac

Jacques René Chirac (, , ; 29 November 193226 September 2019) was a Politics of France, French politician who served as President of France from 1995 to 2007. Chirac was previously Prime Minister of France from 1974 to 1976 and from 1986 to ...

, at the site of the Vélodrome d'Hiver where 13,000 Jews had been rounded up for deportation to death camps in July 1942. "," he said ("France, on that day 6 July 1942 committed the irreparable. Breaking its word, it handed those who were under its protection over to their executioners"). "" ("the criminal folly of the occupiers was seconded by the French, by the French state").

On 16 July 2017, also at a ceremony at the Vel' d'Hiv' site, President Emmanuel Macron

Emmanuel Macron (; born 21 December 1977) is a French politician who has served as President of France since 2017. ''Ex officio'', he is also one of the two Co-Princes of Andorra. Prior to his presidency, Macron served as Minister of Econ ...

denounced the historical revisionism that denied France's responsibility for the 1942 round-up and subsequent deportation of 13,000 Jews. "It was indeed France that organised this", Macron insisted, French police collaborating with the Nazis. “Not a single German” was directly involved, he said, but French police collaborating with the Nazis. Macron was even more specific than Chirac had been in stating that the Government during the War was certainly that of France. “It is convenient to see the Vichy regime as born of nothingness, returned to nothingness. Yes, it’s convenient, but it is false. We cannot build pride upon a lie,” he said. Macron made a subtle reference to Chirac's remark when he added, "I say it again here. It was indeed France that organized the round-up, the deportation, and thus, for almost all, death."

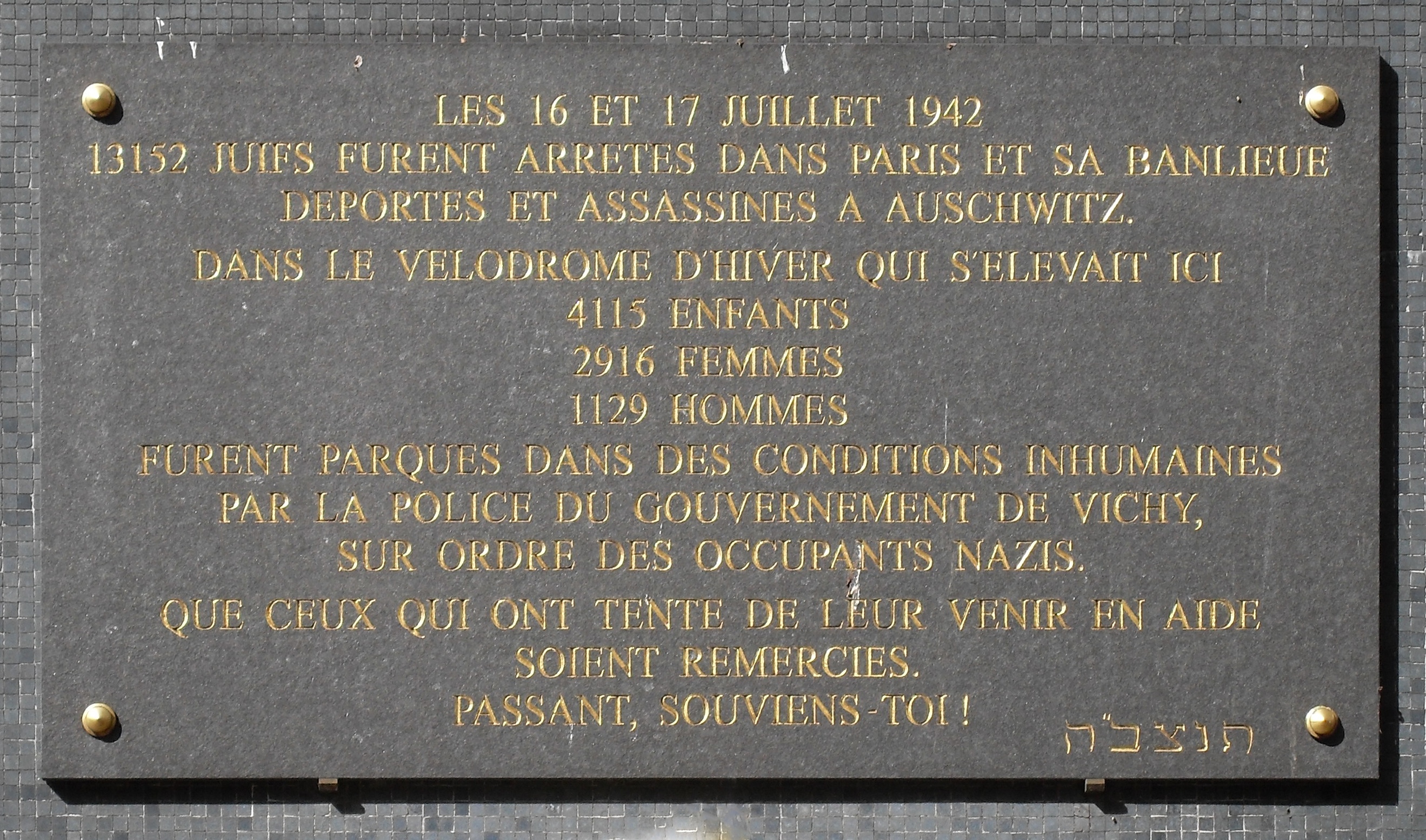

A plaque marking the Rafle du Vel' d'Hiv' was placed on the track building after the War and moved to 8 boulevard de Grenelle in 1959. On 3 February 1993, President Mitterrand commissioned a monument to be erected on the site. It stands now on a curved base, to represent the cycle track, on the edge of the quai de Grenelle. It is the work of the sculptor

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable sc ...

Walter Spitzer and the architect Mario Azagury. Spitzer and his family were survivors of deportation to Auschwitz. The statues represent all deportees but especially those of the Vel' d'Hiv'. The sculptures include children, a pregnant woman and a sick man. The words on the Mitterrand-era monument still differentiate between the French Republic and the Vichy Government that ruled during WW II, so they do not accept responsibility for the roundup of the Jews. The words are in French: "", which translate as follows: "The French Republic pays homage to the victims of racist and anti-Semitic persecutions and crimes against humanity committed under the de facto authority called the 'Government of the French State' 1940–1944. Let us never forget." The monument was inaugurated on 17 July 1994. A ceremony is held at the monument every year in July.

Popular culture

The Vélodrome d'Hiver is featured in the 2006 novel ''Sarah's Key'' by Tatiana de Rosnay and in the 2010 film '' Sarah's Key'' based on the novel, as well as the French film '' The Round Up''.References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Velodrome D'hiver Venues of the 1924 Summer Olympics Olympic boxing venues Olympic weightlifting venues Olympic wrestling venues Velodromes in France Sports venues in Paris Cycling in Paris Olympic cycling venues Boxing venues in France