Utica, Tunisia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Utica () was an ancient Phoenician and

''The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Stillwell'', Richard, Macdonald, William L. and McAllister, Marian Holland. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976. 5 May 2007.

Utica was founded as a port located on the trade route leading from

Utica was founded as a port located on the trade route leading from

"The Histories." Book 1

Loeb Classical Library. Vol I. 2 May 2007 The Carthaginian generals

During the

During the

Athenaeus, Deipnosophists, §14.59

/ref>

File:Tunis Utique Colonnes.JPG, Utica columns

File:Tombe punique.jpg,

La baie d'Utique et son ÃĐvolution depuis l'AntiquitÃĐ : une rÃĐÃĐvaluation gÃĐoarchÃĐologique

Âŧ, ''AntiquitÃĐs africaines'', vol. 31, 1995, pp. 7â51 * Chelbi, Fethi. ''Utique la splendide'', ÃĐd. Agence nationale du patrimoine, Tunis, 1996 * Cintas, Pierre. ÂŦ Nouvelles recherches à Utique Âŧ, ''Karthago''. number 5, 1954, pp. 86â155 * Colozier, Ãtiennette. ÂŦ Quelques monuments inÃĐdits d'Utique Âŧ, ''MÃĐlanges d'archÃĐologie et d'histoire'', vol. 64, numÃĐro64, 1952, pp. 67â86

* . * Hatto Gross, Walter. ''Utica''. In: Der Kleine Pauly (KlP). Band 5, Stuttgart 1975, Sp. 1081 f. * LÃĐzine, Alexandre. ''Carthage-Utique. Ãtudes d'architecture et d'urbanisme'', ÃĐd. CNRS, Paris, 1968 * Paskoff, Roland et al., ÂŦ L'ancienne baie d'Utique : du tÃĐmoignage des textes à celui des images satellitaires Âŧ, ''Mappemonde'', numÃĐro1/1992, pp. 30â34

* Ville, G. ÂŦ La maison de la mosaÃŊque de la chasse à Utique Âŧ, ''Karthago'', numÃĐro11, 1961â1962, pp. 17â76

Utica (in Italian)

{{Phoenician cities and colonies navbox Populated places established in the 8th century BC Populated places disestablished in the 7th century Phoenician colonies in Tunisia Roman towns and cities in Tunisia Carthage Ancient Berber cities Catholic titular sees in Africa Ancient Greek geography of North Africa

Carthaginian The term Carthaginian ( la, Carthaginiensis ) usually refers to a citizen of Ancient Carthage.

It can also refer to:

* Carthaginian (ship), a three-masted schooner built in 1921

* Insurgent privateers; nineteenth-century South American privateers, ...

city located near the outflow of the Medjerda River

The Medjerda River ( ar, ŲاØŊŲ Ų

ØŽØąØŊØĐ), the classical Bagrada, is a river in North Africa flowing from northeast Algeria through Tunisia before emptying into the Gulf of Tunis and Lake of Tunis. With a length of , it is the longest river ...

into the Mediterranean, between Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

in the south and Hippo Diarrhytus

Bizerte or Bizerta ( ar, ØĻŲØēØąØŠ, translit=Binzart , it, Biserta, french: link=no, BizÃĐrte) the classical Hippo, is a city of Bizerte Governorate in Tunisia. It is the northernmost city in Africa, located 65 km (40mil) north of the cap ...

(present-day Bizerte) in the north. It is traditionally considered to be the first colony to have been founded by the Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

ns in North Africa. After Carthage's loss to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

in the Punic Wars

The Punic Wars were a series of wars between 264 and 146BC fought between Roman Republic, Rome and Ancient Carthage, Carthage. Three conflicts between these states took place on both land and sea across the western Mediterranean region and i ...

, Utica was an important Roman colony

A Roman (plural ) was originally a Roman outpost established in conquered territory to secure it. Eventually, however, the term came to denote the highest status of a Roman city. It is also the origin of the modern term ''colony''.

Characteri ...

for seven centuries.

Today, Utica no longer exists, and its remains are located in Bizerte Governorate

Bizerte Governorate ( ar, ŲŲاŲØĐ ØĻŲØēØąØŠ ' ) is the northernmost of the 24 governorates of Tunisia. It is in northern Tunisia, approximately rectangular and having a long north coast. It covers an area of 3,750 kmÂē including two lar ...

in Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

â not on the coast where it once lay, but further inland because deforestation and agriculture upriver led to massive erosion and the Medjerda River silted over its original mouth."Utica (Utique) Tunisia"''The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Stillwell'', Richard, Macdonald, William L. and McAllister, Marian Holland. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976. 5 May 2007.

Name

Utica () is an unusual latinization of thePunic

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' â the Latin equivalent of the ...

name () or (). These derived from Phoenician ''ËAtiq'' (), cognate with Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

''Ëatiqah'' () and Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

''Ëatiq'' (, seen in the title of God, "Ancient of Days

Ancient of Days (Aramaic: , ''ĘŋatÄŦq yÅmÄŦn''; Ancient Greek: , ''palaiÃēs hÄmerÃīn''; Latin: ) is a name for God in the Book of Daniel.

The title "Ancient of Days" has been used as a source of inspiration in art and music, denoting the cre ...

"). These all mean "Old" and contrast the settlement with the later colony Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

, whose own name literally meant "New Town". The latinization is a little unusual in that the Latin U more often transcribed the letter W (i.e., waw

Waw or WAW may refer to:

* Waw (letter), a letter in many Semitic abjads

* Waw, the velomobile

* Another spelling for the town Wau, South Sudan

* Waw Township, Burma

*Warsaw Chopin Airport, an international airport serving Warsaw, Poland (IATA ai ...

) in Punic names.

The Greeks called it ážļÏÏΚη.

History

Phoenician colony

Utica was founded as a port located on the trade route leading from

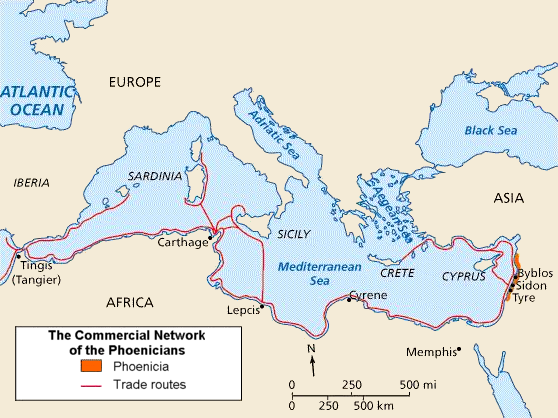

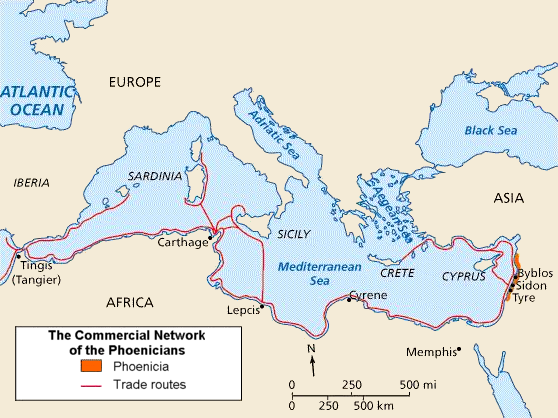

Utica was founded as a port located on the trade route leading from Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

to the Straits of Gibraltar and the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

, facilitating trade in commodities like tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn (from la, stannum) and atomic number 50. Tin is a silvery-coloured metal.

Tin is soft enough to be cut with little force and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, t ...

.Aubet, Maria Eugenia. ''The Phoenicians and the West, Politics, Colonies, and Trade.'' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

The exact founding date of Utica is a matter of controversy. Several classical authors date its foundation to around 1100BC. The archaeological evidence, however, suggests a foundation no earlier than the eighth centuryBC. The inland settlement used Rusucmona ("Cape Eshmun

Eshmun (or Eshmoun, less accurately Esmun or Esmoun; phn, ðĪðĪðĪðĪ '; akk, ð

ðĒðŽðĄ ''Yasumunu'') was a Phoenician god of healing and the tutelary god of Sidon.

History

This god was known at least from the Iron Age period at ...

") on Cape Farina

Cape Farina (french: Cap Farina) is a headland in Bizerte Governorate, Tunisia. It forms the northwestern end of the Gulf of Tunis. The Tunisian towns of Ghar el-Melh (the ancient Castra Delia), Rafraf, Lahmeri, and the beach of Plage Sidi Ali ...

to the northeast as its chief port, although continued silting has rendered the present-day settlement at Ghar el-Melh

Ghar el-Melh ( ar, ØšØ§ØąØ§ŲŲ

ŲØ, ''Ghar al-Milh'', "Salt Grotto"), the classical Rusucmona and CastraDelia and colonial is a town and former port on the southern side of Cape Farina in Bizerte Governorate, Tunisia.

History Phoenician colo ...

a small farming community. Although Carthage was later founded about 40 km from Utica, records suggest "that until 540BC Utica was still maintaining political and economic autonomy in relation to its powerful Carthaginian neighbor".

Carthaginian rule

By the fourth century BC, Utica came under Punic control, but continued to exist as a privileged ally of Carthage. Soon, commercial rivalry created problems between Carthage and Utica. This relationship between Carthage and Utica began to disintegrate after theFirst Punic War

The First Punic War (264â241 BC) was the first of three wars fought between Rome and Carthage, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the early 3rd century BC. For 23 years, in the longest continuous conflict and grea ...

, with the outbreak of rebellion among mercenaries who had not received compensation for their service to Carthage. Originally, Utica refused to participate in this rebellion, so that the Libu

The Libu ( egy, rbw; also transcribed Rebu, Lebu, Lbou, Libou) were an Ancient Libyan tribe of Berber origin, from which the name ''Libya'' derives.

Early history

Their occupation of Ancient Libya is first attested in Egyptian language text ...

forces led by Spendius and Matho laid siege to Utica and nearby Hippocritae.Polybius"The Histories." Book 1

Loeb Classical Library. Vol I. 2 May 2007 The Carthaginian generals

Hanno

Hanno may refer to:

People

* Hanno (given name)

:* Hanunu (8th century BC), Philistine king previously rendered by scholars as "Hanno"

*Hanno ( xpu, ðĪðĪðĪ , '; , ''HannÅn''), common Carthaginian name

:* Hanno the Navigator, Carthagi ...

and Hamilcar __NOTOC__

Hamilcar ( xpu, ðĪðĪðĪðĪ , ,. or , , "Melqart is Gracious"; grc-gre, ážÎžÎŊÎŧΚιÏ, ''HamÃlkas'';) was a common Carthaginian masculine given name. The name was particularly common among the ruling families of ancient Carthage. ...

then came to Utica's defense, managing to raise the siege, but "the severest blow of allâĶ was the defection of Hippacritae and Utica, the only two cities in Libya which hadâĶbravely faced the present warâĶindeed they never had on any occasion given the least sign of hostility to Carthage." Eventually, the forces of Carthage proved victorious, forcing Utica and Hippacritae to surrender after a short siege.

Roman rule

Utica again defied Carthage in theThird Punic War

The Third Punic War (149â146 BC) was the third and last of the Punic Wars fought between Carthage and Rome. The war was fought entirely within Carthaginian territory, in modern northern Tunisia. When the Second Punic War ended in 201 ...

, when it surrendered to Rome shortly before the breakout of war in 150 BC. After its victory, Rome rewarded Utica by granting it an expanse of territory stretching from Carthage to Hippo

The hippopotamus ( ; : hippopotamuses or hippopotami; ''Hippopotamus amphibius''), also called the hippo, common hippopotamus, or river hippopotamus, is a large semiaquatic mammal native to sub-Saharan Africa. It is one of only two extant ...

.Walbank, F. W., Astin, A. E., Frederiksen, M. W., and Ogilvie R. M., eds. ''Rome and the Mediterranean to 133 BC.'' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. Vol. VIII of ''The Cambridge Ancient History''.

As a result of the war, Rome created a new province of Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, and Utica became its capital, which meant that the governor's residence was there along with a small garrison. Over the following decades Utica also attracted Roman citizens who settled there to do business.

Roman Civil War

This is a list of civil wars and organized civil disorder, revolts and rebellions in ancient Rome (Roman Kingdom, Roman Republic, and Roman Empire) until the fall of the Western Roman Empire (753 BCE â 476 CE). For the Eastern Roman Empire or B ...

between the supporters of Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC â 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a leading Roman general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of ...

and Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC â 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman people, Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caes ...

, the Battle of Utica (49 BC)

The Battle of Utica (49 BC) in Caesar's Civil War was fought between Julius Caesar's general Gaius Scribonius Curio and Pompeian legionaries commanded by Publius Attius Varus supported by Numidian cavalry and foot soldiers sent by King Juba I ...

was fought between Julius Caesar's general Gaius Scribonius Curio and Pompeian legionaries commanded by Publius Attius Varus

Publius Attius Varus (died 17 March 45 BC) was the Roman governor of Africa during the civil war between Julius Caesar and Pompey. He declared war against Caesar, and initially fought Gaius Scribonius Curio, who was sent against him in 49 BC.

...

supported by Numidian cavalry and foot soldiers]. Curio defeated the Pompeians and Numidians and drove Varus back into the town of Utica, but then withdrew. Later at the Battle of Thapsus

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and for ...

in 46 BC the remaining Pompeians, including Cato the Younger

Marcus Porcius Cato "Uticensis" ("of Utica"; ; 95 BC â April 46 BC), also known as Cato the Younger ( la, Cato Minor), was an influential conservative Roman senator during the late Republic. His conservative principles were focused on the pr ...

, fled to Utica after being defeated. Caesar pursued them to Utica, meeting no resistance from the inhabitants. Cato, who was the leader of the Pompeians, ensured the escape of his fellow senators and anyone else who desired to leave, then committed suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and s ...

, unwilling to accept the clemency of Caesar.

Displaying their fondness for Cato, "the people of Utica...called Cato their saviour and benefactor... And this they continued to do even when word was brought that Caesar was approaching. They decked his body in splendid fashion, gave it an illustrious escort, and buried it near the sea, where a statue of him now stands, sword in hand". After his death, Cato was given the name of Uticensis, due to the place of his death as well as to his public glorification and burial by the citizens of Utica.

Utica obtained the formal status of a municipium

In ancient Rome, the Latin term (pl. ) referred to a town or city. Etymologically, the was a social contract among ("duty holders"), or citizens of the town. The duties () were a communal obligation assumed by the in exchange for the privi ...

in 36 BC and its inhabitants became members of the Quirina tribe. The city was chosen by the Romans as the place where the governor of their new Africa Province

Africa Proconsularis was a Roman province on the northern African coast that was established in 146 BC following the defeat of Carthage in the Third Punic War. It roughly comprised the territory of present-day Tunisia, the northeast of Algeria, ...

was resident, but the silting of the port (because of the Medjerda River

The Medjerda River ( ar, ŲاØŊŲ Ų

ØŽØąØŊØĐ), the classical Bagrada, is a river in North Africa flowing from northeast Algeria through Tunisia before emptying into the Gulf of Tunis and Lake of Tunis. With a length of , it is the longest river ...

) damaged the importance of Utica.

During the reign of Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC â 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pri ...

, however, the seat of provincial government was moved to a since rebuilt Carthage, although Utica did not lose its status as one of the foremost cities in the province. When Hadrian

Hadrian (; la, Caesar TrÃĒiÄnus HadriÄnus ; 24 January 76 â 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He was born in Italica (close to modern Santiponce in Spain), a Roman ''municipium'' founded by Italic settlers in Hispania B ...

was emperor, Utica requested to become a full Roman colony, but this request was not granted until Septimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (; 11 April 145 â 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa (Roman province), Africa. As a young man he advanced thro ...

, a native of the Province of Africa, took the throne.

The city and all the area east of the ''Fossatum Africae'' was nearly fully romanised

Romanization or romanisation, in linguistics, is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, and ...

by the time of Septimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (; 11 April 145 â 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa (Roman province), Africa. As a young man he advanced thro ...

. According to historian Theodore Mommsen

Christian Matthias Theodor Mommsen (; 30 November 1817 â 1 November 1903) was a German classical scholar, historian, jurist, journalist, politician and archaeologist. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest classicists of the 19th centur ...

, all the inhabitants of Utica spoke Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

and practised Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

in the fourth and early fifth century. The Peutinger Map

' (Latin for "The Peutinger Map"), also referred to as Peutinger's Tabula or Peutinger Table, is an illustrated ' (ancient Roman road map) showing the layout of the ''cursus publicus'', the road network of the Roman Empire.

The map is a 13th-cen ...

from around this time shows the town.

Destruction

In 439 AD, theVandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

captured Utica. In 534 AD, the Byzantines captured it once more. "Excavations at the site have yielded two Punic cemeteries and Roman ruins, including baths and a villa with mosaics".

Diocese of Utica

Roman Utica was a Christian city with an importantdiocese

In Ecclesiastical polity, church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided Roman province, pro ...

in Africa Proconsularis

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

.

Indeed, there are more than a dozen bishops documented in Utica. The first, Aurelius, intervened at the council held at Carthage in 256 AD by St. Cyprian to discuss the question of the "lapsi". Maurus, the second bishop, was accused of apostasy during the Diocletianic Persecution

The Diocletianic or Great Persecution was the last and most severe persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire. In 303, the emperors Diocletian, Maximian, Galerius, and Constantius issued a series of edicts rescinding Christians' legal rights ...

of 303. The third, Victorius, took part in the Council of Arles in 314 AD along with Cecilianus of Carthage; he is mentioned in the ''Roman Martyrology'' on 23 August. Then the fourth, Quietus, assisted at the Council of Carthage (349) proclaimed by Gratus.

At the Conference of Carthage (411)

The Councils of Carthage were church synods held during the 3rd, 4th, and 5th centuries in the city of Carthage in Africa. The most important of these are described below.

Synod of 251

In May 251 a synod, assembled under the presidency of Cypria ...

which saw gathered together the bishops of Nicene Christianity

The original Nicene Creed (; grc-gre, ÎĢÏΞÎēÎŋÎŧÎŋÎ― ÏáŋÏ ÎÎđΚιÎŊÎąÏ; la, Symbolum Nicaenum) was first adopted at the First Council of Nicaea in 325. In 381, it was amended at the First Council of Constantinople. The amended form is a ...

and of heretical Donatism

Donatism was a Christian sect leading to a schism in the Church, in the region of the Church of Carthage, from the fourth to the sixth centuries. Donatists argued that Christian clergy must be faultless for their ministry to be effective and t ...

Victorius II took part for the Church and Gedudus for the Donatists. The historian Morcelli

Stefano Antonio Morcelli (17 January 1737 â 1 January 1822) was an Italian Jesuit scholar, known as an epigraphist. His work ''De stilo Latinarum inscriptionum libri III'', published in three volumes in 1781, which shows a rigorous method, a no ...

added the bishop Gallonianus, present at the Council of Carthage (419)

The Councils of Carthage were church synods held during the 3rd, 4th, and 5th centuries in the city of Carthage in Africa. The most important of these are described below.

Synod of 251

In May 251 a synod, assembled under the presidency of Cyprian ...

, who, according to J. Mesnage, instead belonged to the Diocese of Utina. Then the Bishop Florentius, who intervened at the Synod of Carthage (484)

The Councils of Carthage were church synods held during the 3rd, 4th, and 5th centuries in the city of Carthage in Africa. The most important of these are described below.

Synod of 251

In May 251 a synod, assembled under the presidency of Cyprian ...

, was met by the Vandal king Huneric

Huneric, Hunneric or Honeric (died December 23, 484) was King of the (North African) Vandal Kingdom (477â484) and the oldest son of Gaiseric. He abandoned the imperial politics of his father and concentrated mainly on internal affairs. He was m ...

, after which he was exiled.

Faustinianus participated at the Council of Carthage (525)

The Councils of Carthage were church synods held during the 3rd, 4th, and 5th centuries in the city of Carthage in Africa. The most important of these are described below.

Synod of 251

In May 251 a synod, assembled under the presidency of Cypria ...

. He was followed by the bishop Giunilius, an ecclesiastical writer, who dedicated his works to Primasius of Hadrumetum. In the seventh century was the bishop Flavianus, who assisted at the Council of Carthage (646)

The Councils of Carthage were church synods held during the 3rd, 4th, and 5th centuries in the city of Carthage in Africa. The most important of these are described below.

Synod of 251

In May 251 a synod, assembled under the presidency of Cypria ...

against Monothelitism

Monothelitism, or monotheletism (from el, ΞÎŋÎ―ÎŋÎļÎĩÎŧηÏÎđÏΞÏÏ, monothelÄtismÃģs, doctrine of one will), is a theological doctrine in Christianity, that holds Christ as having only one will. The doctrine is thus contrary to dyothelit ...

; and Potentinus, who was exiled in Spain and intervened at the Council of Toledo (684).

With the Arab conquest, Utica was destroyed and disappeared even as an independent diocese. Only during the early Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

Utica was again a diocese, when the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio espaÃąol), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, MonarquÃa HispÃĄnica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, MonarquÃa CatÃģlica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

conquered the region for some decades and Pedro del Campo was named bishop of the recreated Diocese of Utica in 1516 AD.

Ruins

The site of the ruins of Utica is set on a low hill, composed of several Roman villas. Their walls still preserve decorative floormosaic

A mosaic is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and were particularly pop ...

s. To the northwest of these villas is a Punic

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' â the Latin equivalent of the ...

necropolis, with Punic sarcophagi below the Roman level.

Currently, the site is located about 30 km from Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

and 30 km from Bizerte and near cities with four other historical sites:

* Zhana: village two kilometers from the site and has some important monuments;

* Ghar El Melh : city located on a narrow strip of land between the mountains and the sea and welcoming several fortresses

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

;

* El Alia

El Alia is a town and commune in the Bizerte Governorate, Tunisia.

It was the ancient Uzalis in the Roman province of Africa Proconsularis, which became a Christian bishopric that is included in the Catholic Church's list of titular sees.

It is ...

: city which houses monuments Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, AndalucÃa ) is the southernmost Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a ...

n style;

* Metline

Metline ( aeb, اŲŲ

ا؊ŲŲŲ ) is a commune and town on the Mediterranean coast, in the Bizerte Governorate of northern Tunisia. As of 2004, it had a population of 7,370. It is located approximately north of Tunis, southeast of Bizerte and no ...

: coastal town of Andalucian style.

The House of the Cascade at Utica is typical of most Roman houses excavated in North Africa.

Notable people

* Dionysius of Utica was an ancient Greek writer from Utica./ref>

Gallery

Punic

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' â the Latin equivalent of the ...

Tomb

File:Tunis Utique Ecurie.JPG, House Insula 1, Archaeological site of Utica, Tunisia

File:Tunis Utique Maison.JPG, House Insula 2, Archaeological site of Utica, Tunisia

File:Plan of Utica (1862).jpg, Plan of Utica, Tunisia (1862)

File:Tunis Utique Fontaine.JPG, Fountain in the form of turtle

File:Ruines du site d'Utique, 2013.png, the ruins of Utica

File:TUNISIE UTIQUE 03.JPG, Utica columns 3

File:Tunis Utique Necropole.JPG, Punic

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' â the Latin equivalent of the ...

necropolis

File:Utica1.jpg, Archaeological site of Utica, Tunisia

File:Utique fontaine tortue.jpg, Fountain in the form of turtle 3

See also

*Caesarea

Caesarea () ( he, Ũ§ÖĩŨŨĄÖļŨĻÖ°ŨÖļŨ, ), ''Keysariya'' or ''Qesarya'', often simplified to Keisarya, and Qaysaria, is an affluent town in north-central Israel, which inherits its name and much of its territory from the ancient city of Caesare ...

* Cirta

Cirta, also known by various other names in antiquity, was the ancient Berber and Roman settlement which later became Constantine, Algeria.

Cirta was the capital city of the Berber kingdom of Numidia; its strategically important port city ...

* Thamugadi

Timgad ( ar, ØŠŲŲ

ŲاØŊ, links=, lit=, translit=TÄŦmgÄd, known as Marciana Traiana Thamugadi) was a Roman city in the AurÃĻs Mountains of Algeria. It was founded by the Roman Emperor Trajan around 100 AD. The full name of the city was ''Colo ...

* Lambaesis

Lambaesis (LambÃĶsis), Lambaisis or Lambaesa (''LambÃĻse'' in colonial French), is a Roman archaeological site in Algeria, southeast of Batna and west of Timgad, located next to the modern village of Tazoult. The former bishopric is also a Lat ...

* Thysdrus

Thysdrus was a Carthaginian town and Roman colony near present-day El Djem, Tunisia. Under the Romans, it was the center of olive oil production in the provinces of Africa and Byzacena and was quite prosperous. The surviving amphitheater is a W ...

* Volubilis

Volubilis (; ar, ŲŲŲŲŲ, walÄŦlÄŦ; ber, âĩĄâĩâĩâĩâĩ, wlili) is a partly excavated Berber-Roman city in Morocco situated near the city of Meknes, and may have been the capital of the kingdom of Mauretania, at least from the time of Kin ...

* Leptis Magna

Leptis or Lepcis Magna, also known by other names

Other often refers to:

* Other (philosophy), a concept in psychology and philosophy

Other or The Other may also refer to:

Film and television

* ''The Other'' (1913 film), a German silent fil ...

* Carthago

After the destruction of Punic Carthage in 146 BC, a new city of Carthage (Latin '' CarthÄgÅ'') was built on the same land in the mid- 1st century BC. By the 3rd century, Carthage had developed into one of the largest cities of the Roman Empi ...

* Utica, New York

Utica () is a Administrative divisions of New York, city in the Mohawk Valley and the county seat of Oneida County, New York, United States. The List of cities in New York, tenth-most-populous city in New York State, its population was 65,283 ...

References

Citations

Bibliography

* Chelbi, Fethi.Roland Paskoff

Roland Paskoff (20 March 1933 â 14 September 2005) was a French geologist expert in coastal geomorphology including Holocene tectonics and sea level change. While he was active studying the coast of the countries where he held university posi ...

et Pol Trousset, ÂLa baie d'Utique et son ÃĐvolution depuis l'AntiquitÃĐ : une rÃĐÃĐvaluation gÃĐoarchÃĐologique

Âŧ, ''AntiquitÃĐs africaines'', vol. 31, 1995, pp. 7â51 * Chelbi, Fethi. ''Utique la splendide'', ÃĐd. Agence nationale du patrimoine, Tunis, 1996 * Cintas, Pierre. ÂŦ Nouvelles recherches à Utique Âŧ, ''Karthago''. number 5, 1954, pp. 86â155 * Colozier, Ãtiennette. ÂŦ Quelques monuments inÃĐdits d'Utique Âŧ, ''MÃĐlanges d'archÃĐologie et d'histoire'', vol. 64, numÃĐro64, 1952, pp. 67â86

* . * Hatto Gross, Walter. ''Utica''. In: Der Kleine Pauly (KlP). Band 5, Stuttgart 1975, Sp. 1081 f. * LÃĐzine, Alexandre. ''Carthage-Utique. Ãtudes d'architecture et d'urbanisme'', ÃĐd. CNRS, Paris, 1968 * Paskoff, Roland et al., ÂŦ L'ancienne baie d'Utique : du tÃĐmoignage des textes à celui des images satellitaires Âŧ, ''Mappemonde'', numÃĐro1/1992, pp. 30â34

* Ville, G. ÂŦ La maison de la mosaÃŊque de la chasse à Utique Âŧ, ''Karthago'', numÃĐro11, 1961â1962, pp. 17â76

External links

*Utica (in Italian)

{{Phoenician cities and colonies navbox Populated places established in the 8th century BC Populated places disestablished in the 7th century Phoenician colonies in Tunisia Roman towns and cities in Tunisia Carthage Ancient Berber cities Catholic titular sees in Africa Ancient Greek geography of North Africa