Uriel da Costa on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Uriel da Costa (; also Acosta or d'Acosta; c. 1585 – April 1640) was a Portuguese philosopher and

Uriel da Costa (; also Acosta or d'Acosta; c. 1585 – April 1640) was a Portuguese philosopher and

At about the same time (in Hamburg or Amsterdam) Costa was working on a second treatise. Three chapters of the unpublished manuscript were stolen, and formed the target for a traditionalist rebuttal quickly published by Semuel da Silva of Hamburg; so Costa enlarged his book and the printed version already contains responses and revisions to the crux of the tract.

In 1623 Costa published the Portuguese book (Examination of Pharisaic Traditions). Costa's second work spans more than 200 pages. In the first part it develops his earlier ''Propositons'', taking into account Modena's responses and corrections. In the second part he adds his newer views that the

At about the same time (in Hamburg or Amsterdam) Costa was working on a second treatise. Three chapters of the unpublished manuscript were stolen, and formed the target for a traditionalist rebuttal quickly published by Semuel da Silva of Hamburg; so Costa enlarged his book and the printed version already contains responses and revisions to the crux of the tract.

In 1623 Costa published the Portuguese book (Examination of Pharisaic Traditions). Costa's second work spans more than 200 pages. In the first part it develops his earlier ''Propositons'', taking into account Modena's responses and corrections. In the second part he adds his newer views that the

Index

*

International committee Uriel da Costa

* Bertao, David

The Tragic Life of Uriel Da Costa

Who Was Uriel Da Costa?

by Dr. Henry

Uriel da Costa (; also Acosta or d'Acosta; c. 1585 – April 1640) was a Portuguese philosopher and

Uriel da Costa (; also Acosta or d'Acosta; c. 1585 – April 1640) was a Portuguese philosopher and skeptic

Skepticism, also spelled scepticism, is a questioning attitude or doubt toward knowledge claims that are seen as mere belief or dogma. For example, if a person is skeptical about claims made by their government about an ongoing war then the ...

who was born Christian, but returned to Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in t ...

and ended up questioning the Catholic and rabbinic

Rabbinic Judaism ( he, יהדות רבנית, Yahadut Rabanit), also called Rabbinism, Rabbinicism, or Judaism espoused by the Rabbanites, has been the mainstream form of Judaism since the 6th century CE, after the codification of the Babylonian ...

institutions of his time.

Life

Many details about his life appear in his short autobiography, but over the past two centuries documents uncovered in Portugal, Amsterdam, Hamburg and more have changed and added much in the picture. Costa was born inPorto

Porto or Oporto () is the second-largest city in Portugal, the capital of the Porto District, and one of the Iberian Peninsula's major urban areas. Porto city proper, which is the entire municipality of Porto, is small compared to its metropol ...

with the name Gabriel da Costa Fiuza. His ancestors were ''Cristãos-novos'', or New Christians

New Christian ( es, Cristiano Nuevo; pt, Cristão-Novo; ca, Cristià Nou; lad, Christiano Muevo) was a socio-religious designation and legal distinction in the Spanish Empire and the Portuguese Empire. The term was used from the 15th century ...

, converted from Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in t ...

to Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

by state edict at 1497. His father was a well-off international merchant and tax-farmer.

Studying canon law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is th ...

in the University of Coimbra

The University of Coimbra (UC; pt, Universidade de Coimbra, ) is a public research university in Coimbra, Portugal. First established in Lisbon in 1290, it went through a number of relocations until moving permanently to Coimbra in 1537. The u ...

intermittently between 1600 and 1608, he began to read the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts ...

and contemplate it seriously. Costa also occupied an ecclesiastical office. In his autobiography Costa pictured his family as devout Catholics. However they had been subjects to several investigations by the Inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

, suggesting they were Conversos

A ''converso'' (; ; feminine form ''conversa''), "convert", () was a Jew who converted to Catholicism in Spain or Portugal, particularly during the 14th and 15th centuries, or one of his or her descendants.

To safeguard the Old Christian p ...

, more or less close to Jewish customs. Gabriel explicitly supported the adherence to Mosaic

A mosaic is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and were particularly pop ...

prescriptions as well as traditional ones.

After his father died, the family came into greater financial difficulties due to some debts that had not been paid. In 1614 they changed this predicament as they sneaked out of Portugal with a significant sum of money they previously collected as tax-farmers for Jorge de Mascarenhas. Then the family headed to two major Sephardic diaspora communities. Newly circumcised, and with new Jewish names, two brothers settled in Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the capital and most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population of 907,976 within the city proper, 1,558,755 in the urban ar ...

, and two with their mother in Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

. Gabriel was in the latter city, and became Uriel for the Jewish neighbors, and Adam Romez for outside relations, presumably because he was wanted in Portugal. All resumed their international trade business.

Upon arriving there, Costa quickly became disenchanted with the kind of Judaism he saw in practice. He came to believe that the rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as ''semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of ...

nic leadership was too consumed by ritual

A ritual is a sequence of activities involving gestures, words, actions, or objects, performed according to a set sequence. Rituals may be prescribed by the traditions of a community, including a religious community. Rituals are characterized ...

ism and legalistic posturing. His earliest known written message is known as ''Propostas contra a Tradição'' (Propositions against the Tradition). In eleven short theses he called into question the disparity between certain Jewish customs and a literal reading of the Law of Moses, and more generally tried to prove from reason and scripture that this system of law is sufficient. In 1616 the text was dispatched to the leaders of the prominent Jewish community in Venice. The Venetians ruled against it and prompted the Hamburg community to sanction Costa with a ''herem'', or excommunication. The ''Objections'' are extant only as quotes and paraphrases in ''Magen ṿe-tsinah (מגן וצנה''; "Shield and Buckler"), a longer rebuttal by Leon of Modena

Leon de Modena or in Hebrew name Yehudah Aryeh Mi-Modena (1571–1648) was a Jewish scholar born in Venice to a family whose ancestors migrated to Italy after an expulsion of Jews from France.

Life

He was a precocious child and grew up to be a re ...

, of the Venice community, who responded to religious queries about Costa sent by the Hamburg Jewish authorities.

Costa's 1616 attempts resulted in official excommunication in Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isla ...

and Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

. It is not known what effect this had on his life; Costa barely mentions it in his autobiography, and he would continue his international business. In 1623 he moved to Amsterdam for an unknown reason. The leaders of the Amsterdam Sephardic community were troubled by the arrival of a known heretic, staged a hearing and approved the excommunication set by the previous authorities.

At about the same time (in Hamburg or Amsterdam) Costa was working on a second treatise. Three chapters of the unpublished manuscript were stolen, and formed the target for a traditionalist rebuttal quickly published by Semuel da Silva of Hamburg; so Costa enlarged his book and the printed version already contains responses and revisions to the crux of the tract.

In 1623 Costa published the Portuguese book (Examination of Pharisaic Traditions). Costa's second work spans more than 200 pages. In the first part it develops his earlier ''Propositons'', taking into account Modena's responses and corrections. In the second part he adds his newer views that the

At about the same time (in Hamburg or Amsterdam) Costa was working on a second treatise. Three chapters of the unpublished manuscript were stolen, and formed the target for a traditionalist rebuttal quickly published by Semuel da Silva of Hamburg; so Costa enlarged his book and the printed version already contains responses and revisions to the crux of the tract.

In 1623 Costa published the Portuguese book (Examination of Pharisaic Traditions). Costa's second work spans more than 200 pages. In the first part it develops his earlier ''Propositons'', taking into account Modena's responses and corrections. In the second part he adds his newer views that the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

'' immortality of the soul Christian mortalism is the Christian belief that the human soul is not naturally immortal and may include the belief that the soul is “sleeping” after death until the Resurrection of the Dead and the Last Judgment, a time known as the inte ...

. Costa believed that this was not an idea deeply rooted in biblical Judaism, but rather had been formulated primarily by later '' immortality of the soul Christian mortalism is the Christian belief that the human soul is not naturally immortal and may include the belief that the soul is “sleeping” after death until the Resurrection of the Dead and the Last Judgment, a time known as the inte ...

Pharisaic

The Pharisees (; he, פְּרוּשִׁים, Pərūšīm) were a Jewish social movement and a school of thought in the Levant during the time of Second Temple Judaism. After the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, Pharisaic beliefs b ...

rabbis, and promoted to a Jewish principles of faith

There is no established formulation of principles of faith that are recognized by all branches of Judaism. Central authority in Judaism is not vested in any one person or group - although the Sanhedrin, the supreme Jewish religious court, would ...

. The work further pointed out the discrepancies between biblical Judaism and Rabbinic Judaism

Rabbinic Judaism ( he, יהדות רבנית, Yahadut Rabanit), also called Rabbinism, Rabbinicism, or Judaism espoused by the Rabbanites, has been the mainstream form of Judaism since the 6th century CE, after the codification of the Babylonia ...

; he declared the latter to be an accumulation of mechanical ceremonies

A ceremony (, ) is a unified ritualistic event with a purpose, usually consisting of a number of artistic components, performed on a special occasion.

The word may be of Etruscan origin, via the Latin '' caerimonia''.

Church and civil (secular ...

and practices. In his view, it was thoroughly devoid of spiritual and philosophical concepts. Costa was relatively early in teaching to Jewish readership in favor of the mortality of the soul, and in appealing exclusively to direct reading of the bible. He cites neither rabbinic authorities nor philosophers of the Aristotelian and Neoplatonic traditions.

The book became very controversial among the local Jewish community, whose leaders reported to the city authorities this was an attack on Christianity as well as on Judaism, and it was burned publicly. He was fined a significant sum. In 1627 Costa was a denizen of Utrecht. The Amsterdam community still had an uncomfortable relationship with him; they queried a Venetian rabbi, Yaakov Ha-Levi, whether his elderly mother is eligible for a burial lot in their city; the next year the mother died and Uriel went back to Amsterdam. Ultimately, the loneliness was too much for him to handle, Around 1633 he accepted the terms of reconciliation, which he does not detail in his autobiography, and was reaccepted into the community.

Shortly after that Costa was tried again; he encountered two Christians who expressed to him their desire to convert to Judaism. In accordance with his views, he dissuaded them from doing so. Based on this and earlier accusations regarding kashrut, he was excommunicated

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

. As he describes it, for seven years he lived in virtual isolation, shunned by his family and embroiled in civil-financial disputes with them. In search for legal help, he decided to go back being "an ape amongst the apes"; he would follow the traditions and practices, but with little real conviction. He sought a way of reconciliation. As a punishment for his heretical views, Costa was publicly given 39 lashes at the Portuguese synagogue in Amsterdam. He was then forced to lie on the floor while the congregation trampled over him. This left him both demoralized and seeking revenge against the man (a cousin or nephew) who brought about his trial, seven years previously.

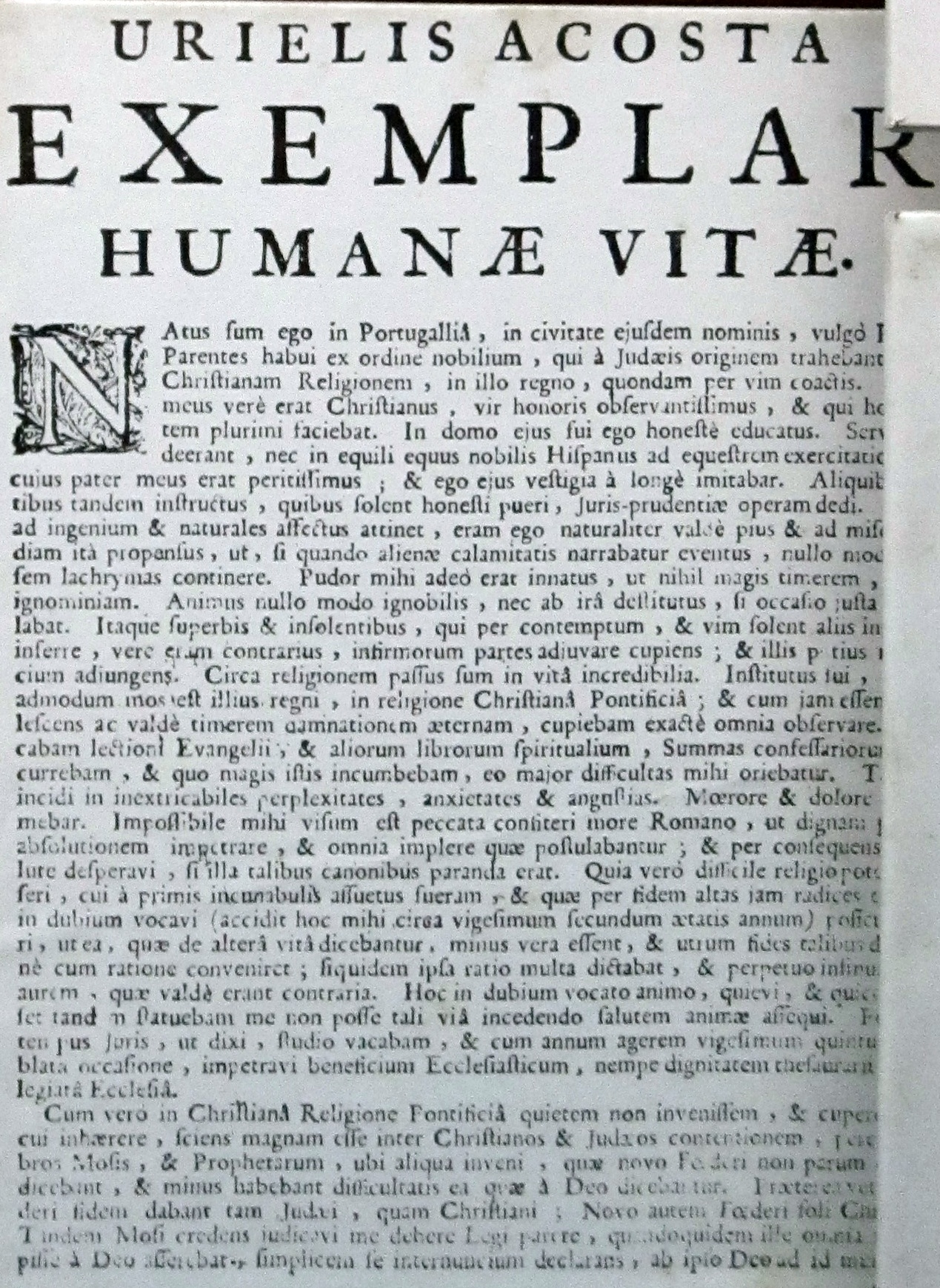

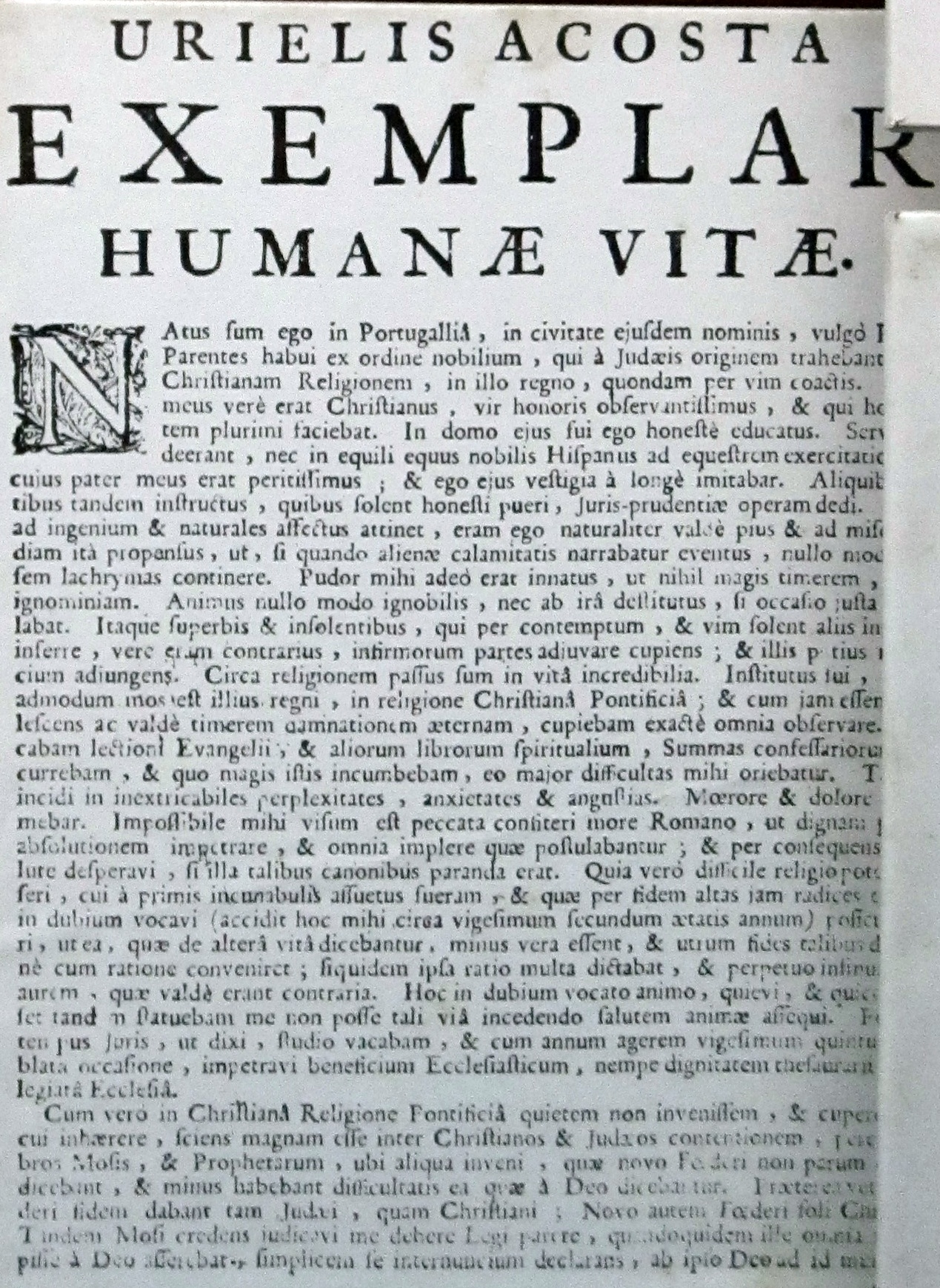

The humiliating ceremony makes the final dramatic point of his autobiography. This document is a few pages long, and was transmitted to print in Latin some decades after his death, with the title ''Exemplar Humanae Vitae'' (Example of a Human Life). It tells the story of his life and intellectual development, his experience as a victim of intolerance

Intolerance may refer to:

* Hypersensitivity

Hypersensitivity (also called hypersensitivity reaction or intolerance) refers to undesirable reactions produced by the normal immune system, including allergies and autoimmunity. They are usual ...

. It also expresses rationalistic and skeptical views: It doubts whether biblical law was divinely sanctioned or whether it was simply written down by Moses. It suggests that all religion

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatural, ...

was a human invention, and specifically rejects formalized, ritualized religion. It sketches a religion to be based only on natural law

Natural law ( la, ius naturale, ''lex naturalis'') is a system of law based on a close observation of human nature, and based on values intrinsic to human nature that can be deduced and applied independently of positive law (the express enacte ...

, as god has no use for empty ceremony, nor for violence and strife.

Two reports agree that Costa committed suicide in Amsterdam in 1640: Johannes Müller, a Protestant theologian of Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

gives the time as April, and Amsterdam Remonstrant

The Remonstrants (or the Remonstrant Brotherhood) is a Protestant movement that had split from the Dutch Reformed Church in the early 17th century. The early Remonstrants supported Jacobus Arminius, and after his death, continued to maintain his ...

preacher Philipp van Limborch

Philipp van Limborch (19 June 1633 – 30 April 1712) was a Dutch Remonstrant theologian.

Biography

Limborch was born on 19 June 1633 in Amsterdam, where his father was a lawyer. He received his education at Utrecht, at Leiden, in his native cit ...

adds that he set out to end the lives of both his brother (or nephew) and himself. Seeing his relative approach one day, he grabbed a pistol and pulled the trigger, but it misfired. Then he reached for another, turned it on himself, and fired, dying a reportedly terrible death.

Influence

Ultimately there have been many ways to view Uriel da Costa. In his lifetime, his book ''Examinations'' inspired not only Silva's answer, but alsoMenasseh ben Israel

Manoel Dias Soeiro (1604 – 20 November 1657), better known by his Hebrew name Menasseh ben Israel (), also known as Menasheh ben Yossef ben Yisrael, also known with the Hebrew acronym, MB"Y or MBI, was a Portuguese rabbi, kabbalist, wri ...

's more lasting ''De Resurrectione Mortuorum'' (1636) directed against the "Sadducees", and a listing in the Index of Prohibited Books

The ''Index Librorum Prohibitorum'' ("List of Prohibited Books") was a list of publications deemed heretical or contrary to morality by the Sacred Congregation of the Index (a former Dicastery of the Roman Curia), and Catholics were forbidde ...

.

After his death, his name became synonymous with the ''Exemplar Humanae Vitae''. Müller publicized Costa's excommunication, to make an anachronistic point that some Sephardic Jews of his days are Sadducees. Johann Helwig Willemer made the same point, and implied that this extreme heresy leads to suicide. Pierre Bayle

Pierre Bayle (; 18 November 1647 – 28 December 1706) was a French philosopher, author, and lexicographer. A Huguenot, Bayle fled to the Dutch Republic in 1681 because of religious persecution in France. He is best known for his '' Histori ...

reported the contents of the ''Exemplar'' quite fully, to demonstrate among other things that questioning religion without turning to revelation would bring one to miserable faithlessness.

The later Enlightenment saw Costa's Rational Religion more tolerantly. Herder eulogized him as a crusader of authentic belief. Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—es ...

noted that he quit Judaism for Philosophy. Reimarus embraced Costa's appeal to have legal status based on the Seven Laws of Noah, when he made an analogous argument that Christian states should be at least as tolerant toward modern Deists

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin ''deus'', meaning " god") is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge, and asserts that empirical reason and observation of ...

as ancient Israelites had been.

Internally to Judaism, he has been seen as both a troublemaking heretic or as martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

against the intolerance of the Rabbinic

Rabbinic Judaism ( he, יהדות רבנית, Yahadut Rabanit), also called Rabbinism, Rabbinicism, or Judaism espoused by the Rabbanites, has been the mainstream form of Judaism since the 6th century CE, after the codification of the Babylonian ...

establishment. He has also been seen as a precursor to Baruch Spinoza and to modern biblical criticism.

Costa is also indicative of the difficulty that many '' Marranos'' faced upon their arrival in an organized Jewish community. As a Crypto-Jew

Crypto-Judaism is the secret adherence to Judaism while publicly professing to be of another faith; practitioners are referred to as "crypto-Jews" (origin from Greek ''kryptos'' – , 'hidden').

The term is especially applied historically to Sp ...

in Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

, he read the Bible and was impressed by it. Yet upon confronting an organized Rabbinic community, he was not equally impressed by the established ritual and religious doctrine of Rabbinical Judaism, such as the Oral Law

An oral law is a code of conduct in use in a given culture, religion or community application, by which a body of rules of human behaviour is transmitted by oral tradition and effectively respected, or the single rule that is orally transmitted.

M ...

. As da Costa himself pointed out, traditional Pharisee and Rabbinic doctrine had been contested in the past by the Sadducees

The Sadducees (; he, צְדוּקִים, Ṣədūqīm) were a socio- religious sect of Jewish people who were active in Judea during the Second Temple period, from the second century BCE through the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE. T ...

and the present by the Karaites.

Works based upon Costa's life

* In 1846, in the midst of theliberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

milieu that led to the Revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europea ...

, the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

writer Karl Gutzkow

Karl Ferdinand Gutzkow ( in Berlin – in Sachsenhausen) was a German writer notable in the Young Germany movement of the mid-19th century.

Life

Gutzkow was born of an extremely poor family, not proletarian, but of the lowest and most meni ...

(1811–1878) wrote ''Uriel Acosta'', a play about Costa's life. This would later become the first classic play to be translated into Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ve ...

, and it was a longtime standard of Yiddish theater

Yiddish theatre consists of plays written and performed primarily by Jews in Yiddish, the language of the Central European Ashkenazi Jewish community. The range of Yiddish theatre is broad: operetta, musical comedy, and satiric or nostalgic rev ...

; Uriel Acosta is the signature role of the actor Rafalesco, the protagonist of Sholem Aleichem

)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Pereiaslav, Russian Empire

, death_date =

, death_place = New York City, U.S.

, occupation = Writer

, nationality =

, period =

, genre = Novels, sh ...

's '' Wandering Stars''. The first translation into Yiddish was by Osip Mikhailovich Lerner Osip Mikhailovich Lerner (13 January 1847 – 23 January 1907), also known as Y. Y. (Yosef Yehuda) Lerner, was a 19th-century Russian Jewish intellectual, writer, and critic. Originally a ''maskil''—a propagator of the ''Has ...

, who staged the play at the Mariinski Theater in Odessa, Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

(then part of Imperial Russia) in 1881, shortly after the assassination of Tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East and South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" in the European medieval sense of the ter ...

Alexander II. Abraham Goldfaden

Abraham Goldfaden (Yiddish: אַבֿרהם גאָלדפֿאַדען; born Avrum Goldnfoden; 24 July 1840 – 9 January 1908), also known as Avram Goldfaden, was a Russian-born Jewish poet, playwright, stage director and actor in the languages Yid ...

rapidly followed with a rival production, an operetta, at Odessa's Remesleni Club. Georgian composer Tamara Vakhvakhishvili Composer Tamara Nikolayevna Vakhvakhishvili (23 December 1893 – 1976) was born in Warsaw, but lived much of her life in Georgia, where she was awarded the title of Honored Artist of the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Vakhvakhishvili studied ...

also composed music for the play.

* Israel Rosenberg

Israel (also Yisroel or Yisrol) Rosenberg (c. 1850 – 1903 or 1904; Yiddish/Hebrew: ישראל ראָזענבערג) founded the first Yiddish theater troupe in Imperial Russia.

Life

Having been a "hole-and-corner lawyer" (without a diplom ...

promptly followed with his own translation for a production in Łódź

Łódź, also rendered in English as Lodz, is a city in central Poland and a former industrial centre. It is the capital of Łódź Voivodeship, and is located approximately south-west of Warsaw. The city's coat of arms is an example of cant ...

(in modern-day Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

). Rosenberg's production starred Jacob Adler

Jacob Pavlovich Adler (Yiddish: יעקבֿ פּאַװלאָװיטש אַדלער; born Yankev P. Adler; February 12, 1855 – April 1, 1926)IMDB biography was a Jewish actor and star of Yiddish theater, first in Odessa, and later in London and ...

in the title role; the play would remain a signature piece in Adler's repertoire to the end of his stage career, the first of the several roles through which he developed the persona that he referred to as "the Grand Jew" (see also Adler's ''Memoir'' in the References below).

* Hermann Jellinek (brother of Adolf Jellinek

Adolf Jellinek ( he, אהרן ילינק ''Aharon Jelinek''; 26 June 1821 in Drslavice, Moravia – 28 December 1893 in Vienna) was an Austrian rabbi and scholar. After filling clerical posts in Leipzig (1845–1856), he became a preacher at t ...

) wrote a book entitled ''Uriel Acosta'' (1848).

* Israel Zangwill

Israel Zangwill (21 January 18641 August 1926) was a British author at the forefront of cultural Zionism during the 19th century, and was a close associate of Theodor Herzl. He later rejected the search for a Jewish homeland in Palestine and ...

used the life of Uriel da Costa as one of several fictionalized biographies in his book ''Dreamers of the Ghetto''.

* Agustina Bessa-Luís, Portuguese writer (1922–2019), published in 1984 the novel ''Um Bicho da Terra'' ("An Animal of the Earth") based on Uriel's life.

Writings

* (Propositions against the Tradition), ca. 1616. An untitled letter addressed at certain Rabbis, opposing their extra-biblical traditions. * (Examination of Pharisaic Traditions), 1623. Here, Costa argues that the humansoul

In many religious and philosophical traditions, there is a belief that a soul is "the immaterial aspect or essence of a human being".

Etymology

The Modern English noun '' soul'' is derived from Old English ''sāwol, sāwel''. The earliest atte ...

is not immortal

Immortality is the ability to live forever, or eternal life.

Immortal or Immortality may also refer to:

Film

* ''The Immortals'' (1995 film), an American crime film

* ''Immortality'', an alternate title for the 1998 British film ''The Wisdom of ...

.

* (Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

for ''Example of a human life''), 1640. Costa's life, questions the authorship of Torah, and expresses trust in natural law.

See also

*Criticism of Judaism

Criticism of Judaism refers to criticism of Jewish religious doctrines, texts, laws, and practices. Early criticism originated in inter-faith polemics between Christianity and Judaism. Important disputations in the Middle Ages gave rise to wi ...

* Criticism of the Talmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cente ...

Notes

References

* * Salomon, Herman Prins, and Sassoon, I.S.D., (trans. and intr.), ''Examination of Pharisaic Traditions'' – : ''Facsimile of the Unique Copy in the Royal Library of Copenhagen'', Leiden, E. J. Brill, 1993. * Nadler, Steven, ''Spinoza: A Life'', Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1999. * Popkin, Richard H., ''Spinoza'', Oxford, Oneworld Publications, 2004. * * Nadler, Steven, ''Menasseh ben Israel, Rabbi of Amsterdam'', New Haven, Yale University Press, 2018. * Adler, Jacob, ''A Life on the Stage: A Memoir'', translated and with commentary by Lulla Rosenfeld, Knopf, New York, 1999, , pp. 200 ''et. seq''. * ''Tradizione e illuminismo in Uriel da Costa. Fonti, temi, questioni dell, edited by O. Proietti e G. Licata, eum, Macerata 201Index

*

External links

International committee Uriel da Costa

* Bertao, David

The Tragic Life of Uriel Da Costa

Who Was Uriel Da Costa?

by Dr. Henry

Henry Abramson

Henry Abramson (born 1963) is the dean of the Lander College of Arts and Sciences in Flatbush, New York. Before that, he served as the Dean for Academic Affairs and Student Services at Touro College's Miami branch (Touro College South). He is no ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Costa, Uriel Da

17th-century philosophers

1580s births

1640 deaths

Dutch Sephardi Jews

Jewish Portuguese writers

Portuguese philosophers

People from Porto

Converts to Judaism from Roman Catholicism

Jewish philosophers

Jewish skeptics

16th-century Sephardi Jews

17th-century Sephardi Jews

Suicides by firearm in the Netherlands

Curiel family

Uriel Acosta

Uriel da Costa (; also Acosta or d'Acosta; c. 1585 – April 1640) was a Portuguese philosopher and skeptic who was born Christian, but returned to Judaism and ended up questioning the Catholic and Rabbinic Judaism, rabbinic institutions of his ti ...

Critics of Judaism

Skeptics

17th-century Portuguese people

16th-century Portuguese people

Philosophers of religion

17th-century suicides