United States in World War I on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

As U.S. President, it was Wilson who made the key policy decisions over foreign affairs: while the country was at peace, the domestic economy ran on a ''

As U.S. President, it was Wilson who made the key policy decisions over foreign affairs: while the country was at peace, the domestic economy ran on a ''

United States Senate U.S. troops began arriving on the

After the war began in 1914, the United States proclaimed a policy of neutrality despite President Woodrow Wilson's antipathies against the German Empire.

When the German

After the war began in 1914, the United States proclaimed a policy of neutrality despite President Woodrow Wilson's antipathies against the German Empire.

When the German

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

declared war on the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

on April 6, 1917, nearly three years after World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

started. A ceasefire and Armistice was declared on November 11, 1918. Before entering the war, the U.S. had remained neutral, though it had been an important supplier to the United Kingdom, France, and the other powers of the Allies of World War I

The Allies of World War I, Entente Powers, or Allied Powers were a coalition of countries led by France, the United Kingdom, Russia, Italy, Japan, and the United States against the Central Powers of Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ott ...

.

The U.S. made its major contributions in terms of supplies, raw material, and money, starting in 1917. American soldiers under General of the Armies

General of the Armies of the United States, more commonly referred to as General of the Armies, is the highest military rank in the United States Army. The rank has been conferred three times: to John J. Pershing in 1919, as a personal accola ...

John Pershing

General of the Armies John Joseph Pershing (September 13, 1860 – July 15, 1948), nicknamed "Black Jack", was a senior United States Army officer. He served most famously as the commander of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) on the Wes ...

, Commander-in-Chief of the American Expeditionary Force

The American Expeditionary Forces (A. E. F.) was a formation of the United States Army on the Western Front of World War I. The A. E. F. was established on July 5, 1917, in France under the command of General John J. Pershing. It fought along ...

(AEF), arrived at the rate of 10,000 men a day on the Western Front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

* Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a maj ...

in the summer of 1918. During the war, the U.S. mobilized over 4 million military personnel and suffered the loss of 65,000 soldiers. The war saw a dramatic expansion of the United States government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a feder ...

in an effort to harness the war effort

In politics and military planning, a war effort is a coordinated mobilization of society's resources—both industrial and human—towards the support of a military force. Depending on the militarization of the culture, the relative si ...

and a significant increase in the size of the U.S. Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. The armed forces consists of six service branches: the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and Coast Guard. The president of the United States is the ...

.

After a relatively slow start in mobilizing the economy and labor force, by spring 1918, the nation was poised to play a role in the conflict. Under the leadership of President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

, the war represented the climax of the Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

as it sought to bring reform and democracy to the world. There was substantial public opposition to U.S. entry into the war.

Beginning

The American entry into World War I came on April 6, 1917, after a year long effort byPresident

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

to get the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

into the war. Apart from an Anglophile

An Anglophile is a person who admires or loves England, its people, its culture, its language, and/or its various accents.

Etymology

The word is derived from the Latin word ''Anglii'' and Ancient Greek word φίλος ''philos'', meaning "fr ...

element urging early support for the British, American public opinion sentiment for neutrality was particularly strong among Irish Americans

, image = Irish ancestry in the USA 2018; Where Irish eyes are Smiling.png

, image_caption = Irish Americans, % of population by state

, caption = Notable Irish Americans

, population =

36,115,472 (10.9%) alone ...

, German Americans

German Americans (german: Deutschamerikaner, ) are Americans who have full or partial German ancestry. With an estimated size of approximately 43 million in 2019, German Americans are the largest of the self-reported ancestry groups by the Unite ...

and Scandinavian Americans

Nordic and Scandinavian Americans are Americans of Scandinavian and/or Nordic ancestry, including Danish Americans (estimate: 1,453,897), Faroese Americans, Finnish Americans (estimate: 653,222), Greenlandic Americans, Icelandic Americans (e ...

, as well as among church leaders and among women in general. On the other hand, even before World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

had broken out, American opinion had been more negative toward the German Empire than towards any other country in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

. Over time, especially after reports of atrocities in Belgium in 1914 and following the sinking of the passenger liner ''RMS Lusitania'' in 1915, the American people increasingly came to see the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

as the aggressor.

As U.S. President, it was Wilson who made the key policy decisions over foreign affairs: while the country was at peace, the domestic economy ran on a ''

As U.S. President, it was Wilson who made the key policy decisions over foreign affairs: while the country was at peace, the domestic economy ran on a ''laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups ...

'' basis, with American banks making huge loans to Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

— funds that were in large part used to buy munitions, raw materials, and food from across the Atlantic. Until 1917, Wilson made minimal preparations for a land war and kept the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

on a small peacetime footing, despite increasing demands for enhanced preparedness. He did, however, expand the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

.

In 1917, with the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

and widespread disillusionment over the war, and with Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

low on credit, the German Empire appeared to have the upper hand in Europe, while the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

clung to its possessions in the Middle East. In the same year, the German Empire decided to resume unrestricted submarine warfare

Unrestricted submarine warfare is a type of naval warfare in which submarines sink merchant ships such as freighters and tankers without warning, as opposed to attacks per prize rules (also known as "cruiser rules") that call for warships to s ...

against any vessel approaching British waters; this attempt to starve Britain into surrender was balanced against the knowledge that it would almost certainly bring the United States into the war. The German Empire also made a secret offer to help Mexico regain territories lost in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

in an encoded telegram known as the Zimmermann Telegram, which was intercepted by British Intelligence. Publication of that communique outraged Americans just as German U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare ro ...

s started sinking American merchant ships in the North Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe a ...

. Wilson then asked Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

for "a war to end all wars

"The war to end war" (also "The war to end all wars"; originally from the 1914 book '' The War That Will End War'' by H. G. Wells) is a term for the First World War of 1914–1918. Originally an idealistic slogan, it is now mainly used sardonic ...

" that would "make the world safe for democracy", and Congress voted to declare war on the German Empire on April 6, 1917. On December 7, 1917, the U.S. declared war on Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

.H.J.Res.169: Declaration of War with Austria-Hungary, WWIUnited States Senate U.S. troops began arriving on the

Western Front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

* Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a maj ...

in large numbers in 1918.

Neutrality

After the war began in 1914, the United States proclaimed a policy of neutrality despite President Woodrow Wilson's antipathies against the German Empire.

When the German

After the war began in 1914, the United States proclaimed a policy of neutrality despite President Woodrow Wilson's antipathies against the German Empire.

When the German U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare ro ...

''U-20'' sank the British liner on 7 May 1915 with 128 U.S. citizens aboard, Wilson demanded an end to German attacks on passenger ships, and warned that the USA would not tolerate unrestricted submarine warfare

Unrestricted submarine warfare is a type of naval warfare in which submarines sink merchant ships such as freighters and tankers without warning, as opposed to attacks per prize rules (also known as "cruiser rules") that call for warships to s ...

in violation of "American rights" and of "international and obligations." Wilson's Secretary of State, William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

, resigned, believing that the President's protests against the German use of U-boat attacks conflicted with America's official commitment to neutrality. On the other hand, Wilson came under pressure from war hawk

In politics, a war hawk, or simply hawk, is someone who favors war or continuing to escalate an existing conflict as opposed to other solutions. War hawks are the opposite of doves. The terms are derived by analogy with the birds of the same name ...

s led by former president Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

, who denounced German acts as "piracy", and from British delegations under Cecil Spring Rice

Sir Cecil Arthur Spring Rice, (27 February 1859 – 14 February 1918) was a British diplomat who served as British Ambassador to the United States from 1912 to 1918, as which he was responsible for the organisation of British efforts to end ...

and Sir Edward Grey.

U.S. Public opinion reacted with outrage to the suspected German sabotage of Black Tom in Jersey City, New Jersey

Jersey City is the second-most populous city in the U.S. state of New Jersey, after Newark.Kingsland explosion on 11 January 1917 in present-day

American public opinion was divided, with most Americans until early 1917 largely of the opinion that the United States should stay out of the war. Opinion changed gradually, partly in response to German actions in Belgium and the ''Lusitania'', partly as

American public opinion was divided, with most Americans until early 1917 largely of the opinion that the United States should stay out of the war. Opinion changed gradually, partly in response to German actions in Belgium and the ''Lusitania'', partly as

The Preparedness movement had what political scientists call a "realism" philosophy of world affairs—they believed that economic strength and military muscle were more decisive than idealistic crusades focused on causes like democracy and national self-determination. Emphasizing over and over the weak state of national defenses, they showed that the United States' 100,000-man Army, even augmented by the 112,000-strong

The Preparedness movement had what political scientists call a "realism" philosophy of world affairs—they believed that economic strength and military muscle were more decisive than idealistic crusades focused on causes like democracy and national self-determination. Emphasizing over and over the weak state of national defenses, they showed that the United States' 100,000-man Army, even augmented by the 112,000-strong

Garrison's plan unleashed the fiercest battle in peacetime history over the relationship of military planning to national goals. In peacetime, War Department arsenals and Navy yards manufactured nearly all munitions that lacked civilian uses, including warships, artillery, naval guns, and shells. Items available on the civilian market, such as food, horses, saddles, wagons, and uniforms were always purchased from civilian contractors.

Peace leaders like

Garrison's plan unleashed the fiercest battle in peacetime history over the relationship of military planning to national goals. In peacetime, War Department arsenals and Navy yards manufactured nearly all munitions that lacked civilian uses, including warships, artillery, naval guns, and shells. Items available on the civilian market, such as food, horses, saddles, wagons, and uniforms were always purchased from civilian contractors.

Peace leaders like

In January 1917, the German Empire resumed unrestricted submarine warfare in hopes of forcing Britain to begin peace talks. The German Foreign minister,

In January 1917, the German Empire resumed unrestricted submarine warfare in hopes of forcing Britain to begin peace talks. The German Foreign minister,

The war came in the midst of the Progressive Era, when efficiency and expertise were highly valued. Therefore, the federal government set up a multitude of temporary agencies with 50,000 to 1,000,000 new employees to bring together the expertise necessary to redirect the economy into the production of munitions and food necessary for the war, as well as for propaganda purposes.

The war came in the midst of the Progressive Era, when efficiency and expertise were highly valued. Therefore, the federal government set up a multitude of temporary agencies with 50,000 to 1,000,000 new employees to bring together the expertise necessary to redirect the economy into the production of munitions and food necessary for the war, as well as for propaganda purposes.

In 1917 the government was unprepared for the enormous economic and financial strains of the war. Washington hurriedly took direct control of the economy. The total cost of the war came to $33 billion, which was 42 times as large as all Treasury receipts in 1916. A constitutional amendment legitimized income tax in 1913; its original very low levels were dramatically increased, especially at the demand of the Southern progressive elements. North Carolina Congressman

In 1917 the government was unprepared for the enormous economic and financial strains of the war. Washington hurriedly took direct control of the economy. The total cost of the war came to $33 billion, which was 42 times as large as all Treasury receipts in 1916. A constitutional amendment legitimized income tax in 1913; its original very low levels were dramatically increased, especially at the demand of the Southern progressive elements. North Carolina Congressman

World War I saw women taking traditionally men's jobs in large numbers for the first time in

World War I saw women taking traditionally men's jobs in large numbers for the first time in

. ''findingaids.smith.edu''. Smith College Special Collections. Retrieved 2019-09-05. This group helped develop standards for women who were working in industries connected to the war alongside the War Labor Policies Board, of which van Kleeck was also a member. After the war, the Women in Industry Service group developed into the U.S. Women's Bureau, headed by Mary Anderson.

The

The

This corps was formed in 1917 from a call by General John J. Pershing to improve the worsening state of communications on the Western front. Applicants for the Signal Corps Female Telephone Operators Unit had to be bilingual in English and French to ensure that orders would be heard by anyone. Over 7,000 women applied, but only 450 women were accepted. Many of these women were former switchboard operators or employees at telecommunications companies. Despite the fact that they wore Army Uniforms and were subject to Army Regulations (and Chief Operator

On the battlefields of France in spring 1918, the war-weary Allied armies enthusiastically greeted the fresh American troops. They arrived at the rate of 10,000 a day, at a time when the Germans were unable to replace their losses. The Americans won a victory at Cantigny, then again in defensive stands at Chateau-Thierry and Belleau Wood. The Americans helped the British Empire,

On the battlefields of France in spring 1918, the war-weary Allied armies enthusiastically greeted the fresh American troops. They arrived at the rate of 10,000 a day, at a time when the Germans were unable to replace their losses. The Americans won a victory at Cantigny, then again in defensive stands at Chateau-Thierry and Belleau Wood. The Americans helped the British Empire,

online

* Bassett, John Spencer. ''Our War with Germany: A History'' (1919

online edition

* Breen, William J. ''Uncle Sam at Home: Civilian Mobilization, Wartime Federalism, and the Council of National Defense, 1917-1919'' (1984)) * * Capozzola, Christopher. ''Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen'' (2008) * Chambers, John W., II. ''To Raise an Army: The Draft Comes to Modern America'' (1987

online

* Clements, Kendrick A. ''The Presidency of Woodrow Wilson'' (1992) * Coffman, Edward M. ''The War to End All Wars: The American Military Experience in World War I'' (1998), a standard military history

online free to borrow

* Committee on Public Information. ''How the war came to America'' (1917

online

840pp detailing every sector of society * Cooper, John Milton. ''Woodrow Wilson: A Biography'' (2009) * Cooper, John Milton. "The World War and American Memory." ''Diplomatic History'' (2014) 38#4 pp: 727-736. * Doenecke, Justus D. ''Nothing Less than War: A New History of America's Entry into World War I'' (University Press of Kentucky, 2011) * DuBois, W.E. Burghardt

"An Essay Toward a History of the Black Man in the Great War,"

''The Crisis,'' vol. 18, no. 2 (June 1919), pp. 63–87. * Epstein, Katherine C. “The Conundrum of American Power in the Age of World War I,” ''Modern American History'' (2019): 1-21. * Hannigan, Robert E. ''The Great War and American Foreign Policy, 1914–24'' (U of Pennsylvania Press, 2017) * Kang, Sung Won, and Hugh Rockoff. "Capitalizing patriotism: the Liberty loans of World War I." ''Financial History Review'' 22.1 (2015): 45

online

* Kennedy, David M. ''Over Here: The First World War and American Society'' (2004), comprehensive coverag

online

* Malin, James C. ''The United States After the World War'' (1930) * Marrin, Albert. ''The Yanks Are Coming: The United States in the First World War'' (1986

online

* May, Ernest R. ''The World War and American Isolation, 1914-1917'' (1959

online at ACLS e-books

highly influential study * Nash, George H. ''The Life of Herbert Hoover: Master of Emergencies, 1917-1918'' (1996

excerpt and text search

* Paxson, Frederic L. ''Pre-war years, 1913-1917'' (1936) wide-ranging scholarly survey * Paxson, Frederic L. ''American at War 1917-1918'' (1939

online

wide-ranging scholarly survey * Paxson, Frederic L. ''Post-War Years: Normalcy 1918-1923 (1948

online

* Paxson, Frederic L. ed. ''War cyclopedia: a handbook for ready reference on the great war'' (1918

online

* Resch, John P., ed. ''Americans at War: Society, culture, and the home front: volume 3: 1901-1945'' (2005) * Schaffer, Ronald. '' America in the Great War: The Rise of the War-Welfare State'' (1991) * Trask, David F. ''The United States in the Supreme War Council: American War Aims and Inter-Allied Strategy, 1917–1918'' (1961) * Trask, David F. ''The AEF and Coalition Warmaking, 1917–1918'' (199

online free

* Trask, David F ed. ''World War I at home; readings on American life, 1914-1920'' (1969) primary source

online

* Tucker, Spencer C., and Priscilla Mary Roberts, eds. ''The Encyclopedia of World War I: A Political, Social, and Military History'' (5 vol. 2005). worldwide coverage * Van Ells, Mark D. ''America and World War I: A Traveler's Guide'' (2014

excerpt

* Vaughn, Stephen. ''Holding Fast the Inner Lines: Democracy, Nationalism, and the Committee on Public Information'' (U of North Carolina Press, 1980

online

* Venzon, Anne ed. ''The United States in the First World War: An Encyclopedia'' (1995) * ; 904pp; full scale scholarly biography; winner of Pulitzer Prize

online free; 2nd ed. 1965

* * Woodward, David R. ''The American Army and the First World War'' (2014). 484 pp

online review

* Woodward, David R. ''Trial by Friendship: Anglo-American Relations, 1917-1918'' (1993

online

* Young, Ernest William. ''The Wilson Administration and the Great War'' (1922

online edition

* Zieger, Robert H. ''America's Great War: World War I and the American Experience'' (2000)

excerpt

* Capozzola, Chris, et al. "Interchange: World War I." ''Journal of American History'' 102.2 (2015): 463-499. https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/jav474 * Cooper, John Milton Jr. “The World War and American Memory,” ''Diplomatic History'' 38:4 (2014): 727–36. * Jones, Heather. “As the Centenary Approaches: The Regeneration of First World War Historiography” ''Historical Journal'' 56:3 (2013): 857–78, global perspective * Keene, Jennifer, “The United States” in John Horne, ed., ''A Companion to World War I'' (Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), 508–23. * Keene, Jennifer D. "Remembering the 'Forgotten War': American Historiography on World War I." ''Historian'' 78#3 (2016): 439-468. * Rubin, Richard. ''The Last of the Doughboys: The Forgotten Generation and their Forgotten World War'' (2013) * Snell, Mark A., ed. ''Unknown Soldiers: The American Expeditionary Forces in Memory and Remembrance'' (Kent State UP, 2008). * Trout, Steven. ''On the Battlefield of Memory: The First World War and American Remembrance, 1919–1941'' (University of Alabama Press, 2010) * Woodward. David. ''America and World War I: A Selected Annotated Bibliography of English Language Sources'' (2nd ed 2007

excerpt

* Zeiler, Thomas W., Ekbladh, David K., and Montoya, Benjamin C., eds. ''Beyond 1917: The United States and the Global Legacies of the Great War'' (Oxford University Press, 2017)

First-hand accounts of World War I veterans

The Library of Congress Veterans History Project. {{DEFAULTSORT:United States In World War I World War I

Lyndhurst, New Jersey

Lyndhurst is a township in Bergen County, New Jersey, United States. As of the 2010 United States Census, the township's population was 20,554, reflecting an increase of 1,171 (+6.0%) from the 19,383 counted in the 2000 Census, which had in turn ...

.

Crucially, by the spring of 1917, President Wilson's official commitment to neutrality had finally unraveled. Wilson realized he needed to enter the war in order to shape the peace and implement his vision for a League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

at the Paris Peace Conference.

Public opinion

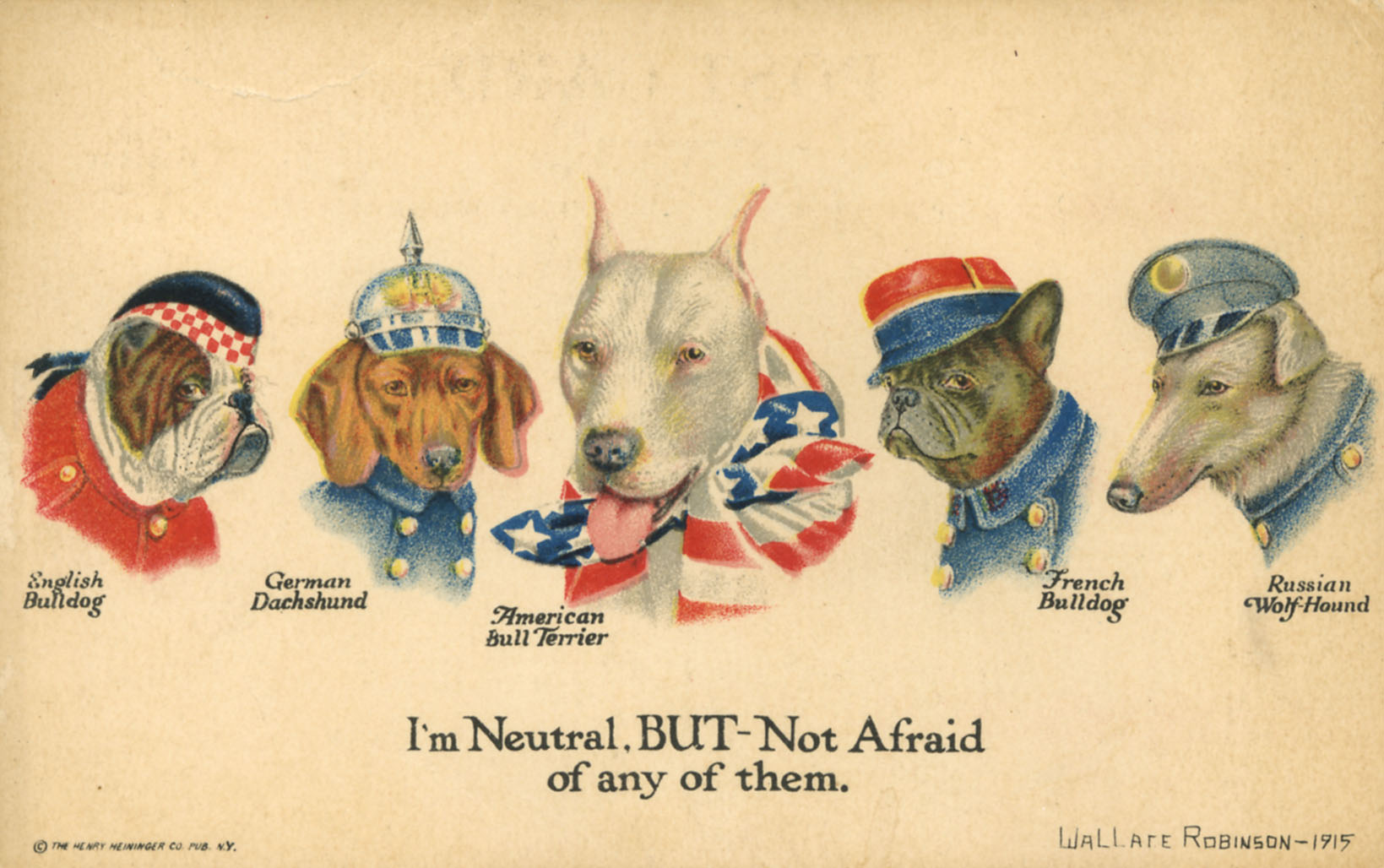

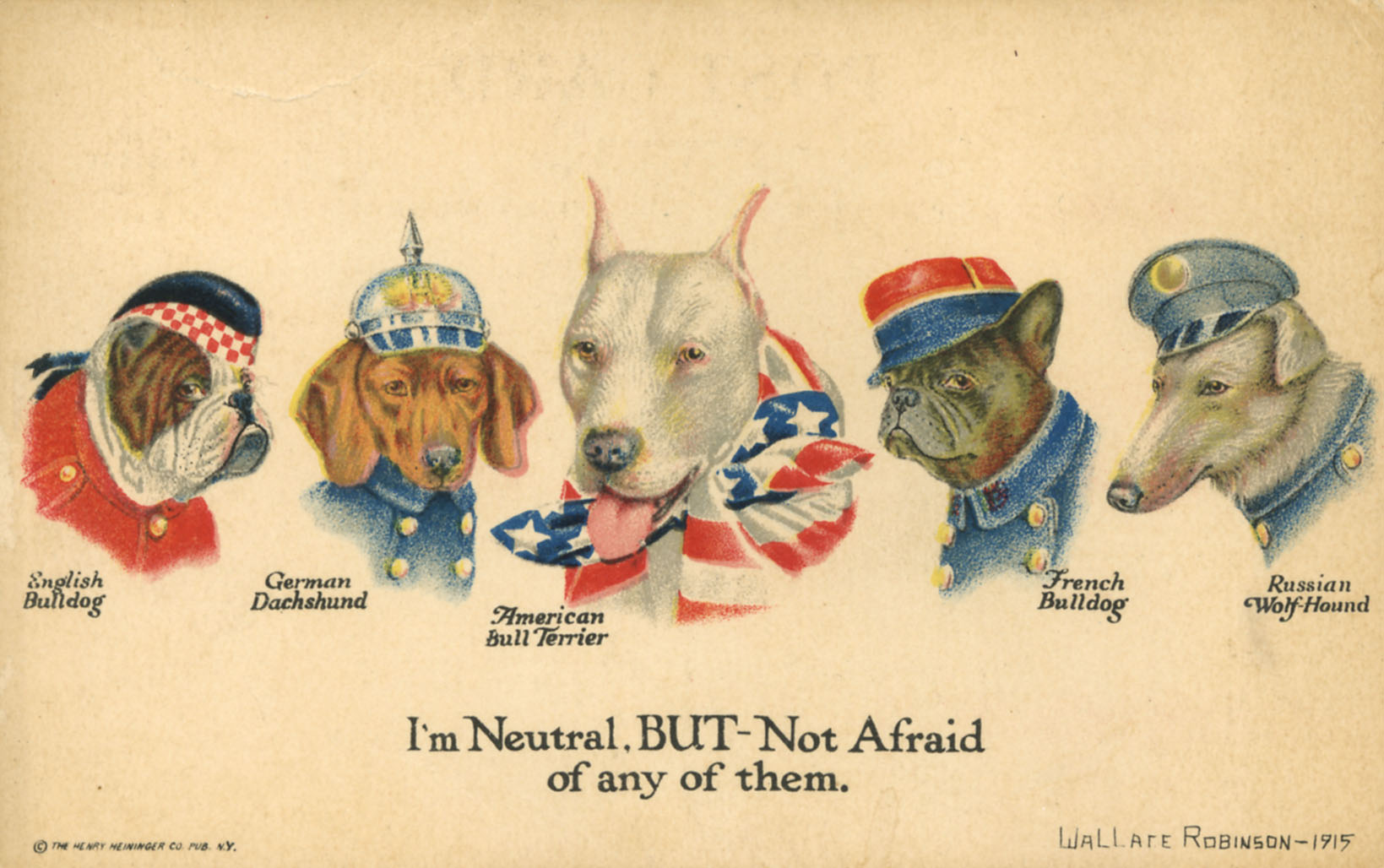

American public opinion was divided, with most Americans until early 1917 largely of the opinion that the United States should stay out of the war. Opinion changed gradually, partly in response to German actions in Belgium and the ''Lusitania'', partly as

American public opinion was divided, with most Americans until early 1917 largely of the opinion that the United States should stay out of the war. Opinion changed gradually, partly in response to German actions in Belgium and the ''Lusitania'', partly as German Americans

German Americans (german: Deutschamerikaner, ) are Americans who have full or partial German ancestry. With an estimated size of approximately 43 million in 2019, German Americans are the largest of the self-reported ancestry groups by the Unite ...

lost influence, and partly in response to Wilson's position that America had to play a role to make the world safe for democracy.

In the general public, there was little if any support for entering the war on the side of the German Empire. The great majority of German Americans, as well as Scandinavian Americans

Nordic and Scandinavian Americans are Americans of Scandinavian and/or Nordic ancestry, including Danish Americans (estimate: 1,453,897), Faroese Americans, Finnish Americans (estimate: 653,222), Greenlandic Americans, Icelandic Americans (e ...

, wanted the United States to remain neutral; however, at the outbreak of war, thousands of U.S. citizens had tried to enlist in the German army. The Irish Catholic community, based in the large cities and often in control of the Democratic Party apparatus, was strongly hostile to helping Britain in any way, especially after the Easter uprising

The Easter Rising ( ga, Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the ...

of 1916 in Ireland. Most of the Protestant church leaders in the United States, regardless of their theology, favored pacifistic solutions whereby the United States would broker a peace. Most of the leaders of the women's movement

The feminist movement (also known as the women's movement, or feminism) refers to a series of social movements and political campaigns for radical and liberal reforms on women's issues created by the inequality between men and women. Such is ...

, typified by Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860 May 21, 1935) was an American Settlement movement, settlement activist, Social reform, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, and author. She was an important leader in the history of s ...

, likewise sought pacifistic solutions. The most prominent opponent of war was industrialist

A business magnate, also known as a tycoon, is a person who has achieved immense wealth through the ownership of multiple lines of enterprise. The term characteristically refers to a powerful entrepreneur or investor who controls, through per ...

Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American industrialist, business magnate, founder of the Ford Motor Company, and chief developer of the assembly line technique of mass production. By creating the first automobile that ...

, who personally financed and led a peace ship to Europe to try to negotiate among the belligerents; no negotiations resulted.

Britain had significant support among intellectuals and families with close ties to Britain. The most prominent leader was Samuel Insull

Samuel Insull (November 11, 1859 – July 16, 1938) was a British-born American business magnate. He was an innovator and investor based in Chicago who greatly contributed to create an integrated electrical infrastructure in the United Stat ...

of Chicago, a leading industrialist who had emigrated from England. Insull funded many propaganda efforts, and financed young Americans who wished to fight by joining the Canadian military.

Preparedness movement

By 1915 Americans were paying much more attention to the war. The sinking of the ''Lusitania'' aroused furious denunciations of German brutality. In Eastern cities a new "Preparedness" movement emerged. It argued that the United States needed to build up immediately strong naval and land forces for defensive purposes; an unspoken assumption was that America would fight sooner or later. The driving forces behind Preparedness were all Republicans, notably GeneralLeonard Wood

Leonard Wood (October 9, 1860 – August 7, 1927) was a United States Army major general, physician, and public official. He served as the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Military Governor of Cuba, and Governor-General of the Philipp ...

, ex-president Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

, and former secretaries of war Elihu Root

Elihu Root (; February 15, 1845February 7, 1937) was an American lawyer, Republican politician, and statesman who served as Secretary of State and Secretary of War in the early twentieth century. He also served as United States Senator from ...

and Henry Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 – October 20, 1950) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. Over his long career, he emerged as a leading figure in U.S. foreign policy by serving in both Republican and D ...

; they enlisted many of the nation's most prominent bankers, industrialists, lawyers and scions of prominent families. Indeed, there emerged an "Atlanticist" foreign policy establishment, a group of influential Americans drawn primarily from upper-class lawyers, bankers, academics, and politicians of the Northeast, committed to a strand of Anglophile internationalism.

The Preparedness movement had what political scientists call a "realism" philosophy of world affairs—they believed that economic strength and military muscle were more decisive than idealistic crusades focused on causes like democracy and national self-determination. Emphasizing over and over the weak state of national defenses, they showed that the United States' 100,000-man Army, even augmented by the 112,000-strong

The Preparedness movement had what political scientists call a "realism" philosophy of world affairs—they believed that economic strength and military muscle were more decisive than idealistic crusades focused on causes like democracy and national self-determination. Emphasizing over and over the weak state of national defenses, they showed that the United States' 100,000-man Army, even augmented by the 112,000-strong National Guard

National Guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

Nat ...

, was outnumbered 20 to one by the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

army; similarly in 1915, the armed forces of Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

and the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

, the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

, Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

, Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia ( Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hu ...

, Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

, Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

and Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

were all larger and more experienced than the United States military.

They called for UMT or "universal military service" under which the 600,000 men who turned 18 every year would be required to spend six months in military training, and then be assigned to reserve units. The small regular army would primarily be a training agency. Public opinion, however, was not willing to go that far.

Both the regular army and the Preparedness leaders had a low opinion of the National Guard, which they saw as politicized, provincial, poorly armed, ill trained, too inclined to idealistic crusading (as against Spain in 1898), and too lacking in understanding of world affairs. The National Guard on the other hand was securely rooted in state and local politics, with representation from a very broad cross section of the U.S. political economy. The Guard was one of the nation's few institutions that (in some northern states) accepted black men on an equal footing with white men.

Democrats respond

The Democratic party saw the Preparedness movement as a threat. Roosevelt, Root and Wood were prospective Republican presidential candidates. More subtly, the Democrats were rooted in localism that appreciated the National Guard, and the voters were hostile to the rich and powerful in the first place. Working with the Democrats who controlled Congress, Wilson was able to sidetrack the Preparedness forces. Army and Navy leaders were forced to testify before Congress to the effect that the nation's military was in excellent shape. In reality, neither theU.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

nor U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage o ...

was in shape for war in terms of manpower, size, military hardware or experience. The Navy had fine ships but Wilson had been using them to threaten Mexico, and the fleet's readiness had suffered. The crews of the ''Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

'' and the ''New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

'', the two newest and largest battleships, had never fired a gun, and the morale of the sailors was low. The Army and Navy air forces were tiny in size. Despite the flood of new weapons systems unveiled in the war in Europe, the Army was paying scant attention. For example, it was making no studies of trench warfare

Trench warfare is a type of land warfare using occupied lines largely comprising Trench#Military engineering, military trenches, in which troops are well-protected from the enemy's small arms fire and are substantially sheltered from artille ...

, poison gas

Many gases have toxic properties, which are often assessed using the LC50 (median lethal dose) measure. In the United States, many of these gases have been assigned an NFPA 704 health rating of 4 (may be fatal) or 3 (may cause serious or perma ...

or tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and good battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful ...

s, and was unfamiliar with the rapid evolution of aerial warfare

Aerial warfare is the use of military aircraft and other flying machines in warfare. Aerial warfare includes bombers attacking enemy installations or a concentration of enemy troops or strategic targets; fighter aircraft battling for contr ...

. The Democrats in Congress tried to cut the military budget in 1915. The Preparedness movement effectively exploited the surge of outrage over the "Lusitania" in May 1915, forcing the Democrats to promise some improvements to the military and naval forces. Wilson, less fearful of the Navy, embraced a long-term building program designed to make the fleet the equal of the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

by the mid-1920s, although this would not come to pass until World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. "Realism" was at work here; the admirals were Mahanians and they therefore wanted a surface fleet of heavy battleships second to none—that is, equal to Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

. The facts of submarine warfare (which necessitated destroyers, not battleships) and the possibilities of imminent war with the German Empire (or with Britain, for that matter), were simply ignored.

Wilson's decision touched off a firestorm. Secretary of War Lindley Garrison

Lindley Miller Garrison (November 28, 1864 – October 19, 1932) was an American lawyer from New Jersey who served as Secretary of War under U.S. President Woodrow Wilson between 1913 and 1916.

Biography

Early years

Lindley Miller Garrison ...

adopted many of the proposals of the Preparedness leaders, especially their emphasis on a large federal reserves and abandonment of the National Guard

National Guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

Nat ...

. Garrison's proposals not only outraged the provincial politicians of both parties, they also offended a strongly held belief shared by the liberal wing of the Progressive movement, that was, that warfare always had a hidden economic motivation. Specifically, they warned the chief warmongers were New York bankers (such as J. P. Morgan) with millions at risk, profiteering munition makers (such as Bethlehem Steel

The Bethlehem Steel Corporation was an American steelmaking company headquartered in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. For most of the 20th century, it was one of the world's largest steel producing and shipbuilding companies. At the height of its succ ...

, which made armor, and DuPont, which made powder) and unspecified industrialists searching for global markets to control. Antiwar critics blasted them. These selfish special interests were too powerful, especially, Senator La Follette noted, in the conservative wing of the Republican Party. The only road to peace was disarmament in the eyes of many.

National debate

Garrison's plan unleashed the fiercest battle in peacetime history over the relationship of military planning to national goals. In peacetime, War Department arsenals and Navy yards manufactured nearly all munitions that lacked civilian uses, including warships, artillery, naval guns, and shells. Items available on the civilian market, such as food, horses, saddles, wagons, and uniforms were always purchased from civilian contractors.

Peace leaders like

Garrison's plan unleashed the fiercest battle in peacetime history over the relationship of military planning to national goals. In peacetime, War Department arsenals and Navy yards manufactured nearly all munitions that lacked civilian uses, including warships, artillery, naval guns, and shells. Items available on the civilian market, such as food, horses, saddles, wagons, and uniforms were always purchased from civilian contractors.

Peace leaders like Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860 May 21, 1935) was an American Settlement movement, settlement activist, Social reform, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, and author. She was an important leader in the history of s ...

of Hull House

Hull House was a settlement house in Chicago, Illinois, United States that was co-founded in 1889 by Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr. Located on the Near West Side of the city, Hull House (named after the original house's first owner Ch ...

and David Starr Jordan

David Starr Jordan (January 19, 1851 – September 19, 1931) was the founding president of Stanford University, serving from 1891 to 1913. He was an ichthyologist during his research career. Prior to serving as president of Stanford Univer ...

of Stanford University redoubled their efforts, and now turned their voices against the President because he was "sowing the seeds of militarism, raising up a military and naval caste." Many ministers, professors, farm spokesmen and labor union leaders joined in, with powerful support from a band of four dozen southern Democrats in Congress who took control of the House Military Affairs Committee. Wilson, in deep trouble, took his cause to the people in a major speaking tour in early 1916, a warm-up for his reelection campaign that fall.

Wilson seemed to have won over the middle classes, but had little impact on the largely ethnic working classes and the deeply isolationist farmers. Congress still refused to budge, so Wilson replaced Garrison as Secretary of War with Newton Baker

Newton Diehl Baker Jr. (December 3, 1871 – December 25, 1937) was an American lawyer, Georgist,Noble, Ransom E. "Henry George and the Progressive Movement." The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, vol. 8, no. 3, 1949, pp. 259–269. w ...

, the Democratic mayor of Cleveland and an outspoken ''opponent'' of preparedness. The upshot was a compromise passed in May 1916, as the war raged on and Berlin was debating whether America was so weak it could be ignored. The Army was to double in size to 11,300 officers and 208,000 men, with no reserves, and a National Guard that would be enlarged in five years to 440,000 men. Summer camps on the Plattsburg model were authorized for new officers, and the government was given $20 million to build a nitrate plant of its own. Preparedness supporters were downcast, the antiwar people were jubilant. The United States would now be too weak to go to war. Colonel Robert L. Bullard

Lieutenant General Robert Lee Bullard (January 5, 1861 – September 11, 1947) was a senior officer of the United States Army. He was involved in conflicts in the American Western Frontier, the Philippines, and World War I, where he commanded ...

privately complained that "Both sides ritain and the German Empiretreat us with scorn and contempt; our fool, smug conceit of superiority has been exploded in our faces and deservedly.". The House gutted the naval plans as well, defeating a "big navy" plan by 189 to 183, and canceling the battleships. The battle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland (german: Skagerrakschlacht, the Battle of the Skagerrak) was a naval battle fought between Britain's Royal Navy Grand Fleet, under Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, and the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet, under Vice ...

(May 31/June 1, 1916) saw the main German High Seas Fleet engage in a monumental yet inconclusive clash with the far stronger Grand Fleet of the Royal Navy. Arguing this battle proved the validity of Mahanian doctrine, the navalists took control in the Senate, broke the House coalition, and authorized a rapid three-year buildup of all classes of warships. A new weapons system, naval aviation, received $3.5 million, and the government was authorized to build its own armor-plate factory. The very weakness of American military power encouraged the German Empire to start its unrestricted submarine attacks in 1917. It knew this meant war with America, but it could discount the immediate risk because the U.S. Army was negligible and the new warships would not be at sea until 1919 by which time the war would be over, Berlin thought, with the German Empire victorious. The notion that armaments led to war was turned on its head: refusal to arm in 1916 led to war in 1917.

War declared

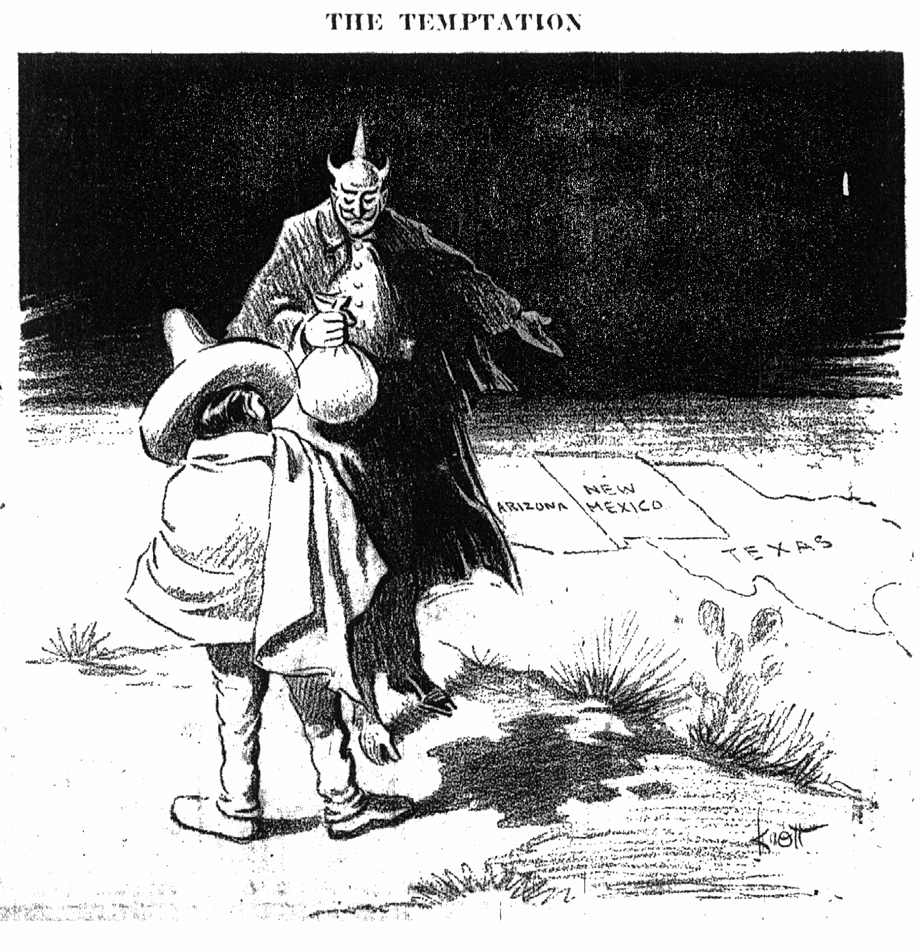

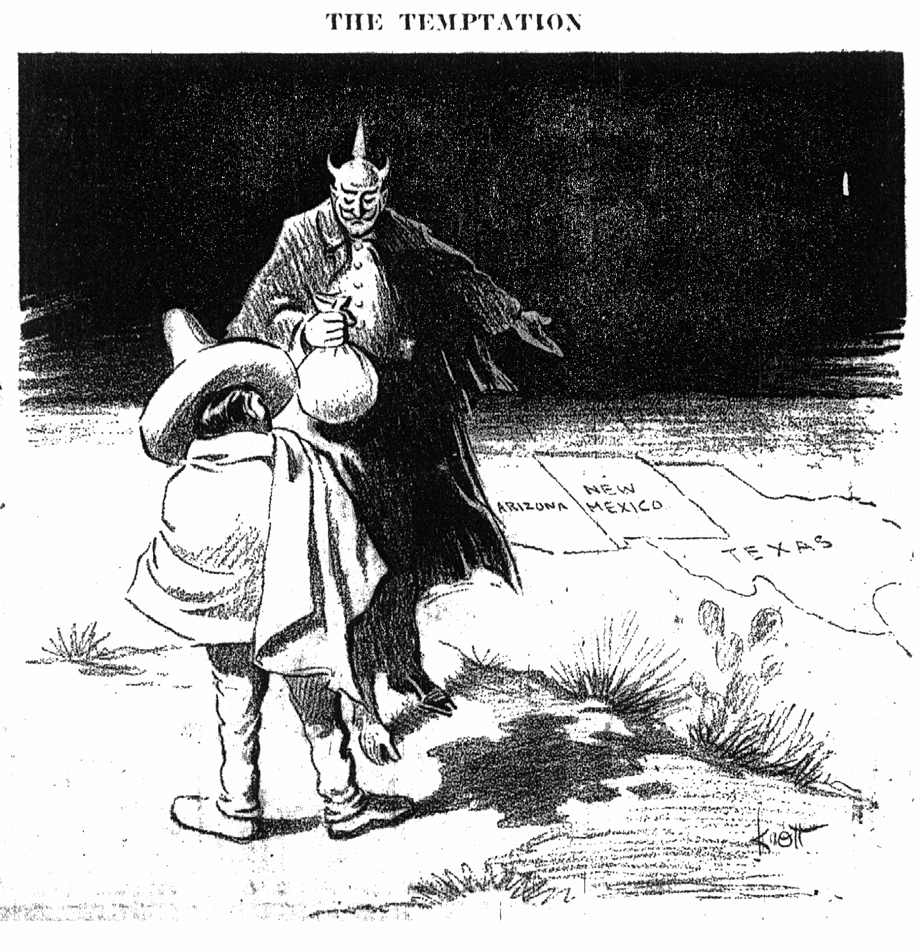

In January 1917, the German Empire resumed unrestricted submarine warfare in hopes of forcing Britain to begin peace talks. The German Foreign minister,

In January 1917, the German Empire resumed unrestricted submarine warfare in hopes of forcing Britain to begin peace talks. The German Foreign minister, Arthur Zimmermann

Arthur Zimmermann (5 October 1864 – 6 June 1940) was State Secretary for Foreign Affairs of the German Empire from 22 November 1916 until his resignation on 6 August 1917. His name is associated with the Zimmermann Telegram during World War ...

invited revolution-torn Mexico to join the war as the German Empire's ally against the United States if the United States declared war on the German Empire in the Zimmermann Telegram. In return, the Germans would send Mexico money and help it recover the territories of Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

, New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe, New Mexico, Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque, New Mexico, Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Albuquerque metropolitan area, Tiguex

, Offi ...

and Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

that Mexico lost during the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

70 years earlier. British intelligence intercepted the telegram and passed the information on to Washington. Wilson released the Zimmerman note to the public and Americans saw it as a ''casus belli

A (; ) is an act or an event that either provokes or is used to justify a war. A ''casus belli'' involves direct offenses or threats against the nation declaring the war, whereas a ' involves offenses or threats against its ally—usually one ...

''—a justification for war.

At first, Wilson tried to maintain neutrality while fighting off the submarines by arming American merchant ships with guns powerful enough to sink German submarines on the surface (but useless when the U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare ro ...

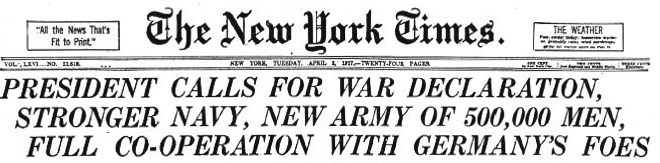

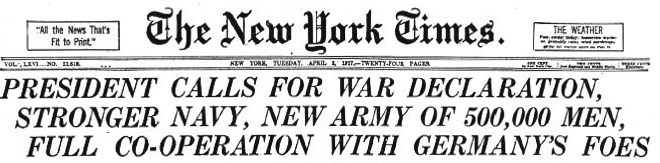

s were under water). After submarines sank seven U.S. merchant ships, Wilson finally went to Congress calling for a declaration of war on the German Empire, which Congress voted on April 6, 1917.

As a result of the Russian February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and some ...

in 1917, the Tsar abdicated and was replaced by a Russian Provisional Government. This helped overcome Wilson's reluctance to having the U.S. fight alongside a country ruled by an absolutist monarch. Pleased by the Provisional Government's pro-war stance, the U.S. accorded the new government diplomatic recognition on March 9, 1917.

Congress declared war on the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

on December 7, 1917, but never made declarations of war against the other Central Powers, Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

, the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

or the various small co-belligerent

Co-belligerence is the waging of a war in cooperation against a common enemy with or without a formal treaty of military alliance. Generally, the term is used for cases where no alliance exists. Likewise, allies may not become co-belligerents in a ...

s allied with the Central Powers. Thus, the United States remained uninvolved in the military campaigns in central and eastern Europe, the Middle East, the Caucasus, North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia and the Pacific.

Home front

The home front required a systematic mobilization of the entire population and the entire economy to produce the soldiers, food supplies, munitions, and money needed to win the war. It took a year to reach a satisfactory state. Although the war had already raged for two years, Washington had avoided planning, or even recognition of the problems that the British and other Allies had to solve on their home fronts. As a result, the level of confusion was high at first. Finally efficiency was achieved in 1918. The war came in the midst of the Progressive Era, when efficiency and expertise were highly valued. Therefore, the federal government set up a multitude of temporary agencies with 50,000 to 1,000,000 new employees to bring together the expertise necessary to redirect the economy into the production of munitions and food necessary for the war, as well as for propaganda purposes.

The war came in the midst of the Progressive Era, when efficiency and expertise were highly valued. Therefore, the federal government set up a multitude of temporary agencies with 50,000 to 1,000,000 new employees to bring together the expertise necessary to redirect the economy into the production of munitions and food necessary for the war, as well as for propaganda purposes.

Food

The most admired agency for efficiency was theUnited States Food Administration

The United States Food Administration (1917–1920) was an independent Federal agency that controlled the production, distribution and conservation of food in the U.S. during the nation's participation in World War I. It was established to preve ...

under Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gre ...

. It launched a massive campaign to teach Americans to economize on their food budgets and grow victory garden

Victory gardens, also called war gardens or food gardens for defense, were vegetable, fruit, and herb gardens planted at private residences and public parks in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and Germany during World War I ...

s in their backyards for family consumption. It managed the nation's food distribution and prices and built Hoover's reputation as an independent force of presidential quality.

Finance

In 1917 the government was unprepared for the enormous economic and financial strains of the war. Washington hurriedly took direct control of the economy. The total cost of the war came to $33 billion, which was 42 times as large as all Treasury receipts in 1916. A constitutional amendment legitimized income tax in 1913; its original very low levels were dramatically increased, especially at the demand of the Southern progressive elements. North Carolina Congressman

In 1917 the government was unprepared for the enormous economic and financial strains of the war. Washington hurriedly took direct control of the economy. The total cost of the war came to $33 billion, which was 42 times as large as all Treasury receipts in 1916. A constitutional amendment legitimized income tax in 1913; its original very low levels were dramatically increased, especially at the demand of the Southern progressive elements. North Carolina Congressman Claude Kitchin

Claude Kitchin (March 24, 1869 – May 31, 1923) was an American politician who served as a member of the United States House of Representatives from the state of North Carolina from 1901 until his death in 1923. A lifelong member of the Democ ...

, chairman of the tax-writing Ways and Means Committee argued that since Eastern businessman had been leaders in calling for war, they should pay for it. In an era when most workers earned under $1000 a year, the basic exemption was $2,000 for a family. Above that level taxes began at the 2 percent rate in 1917, jumping to 12 percent in 1918. On top of that there were surcharges of one percent for incomes above $5,000 to 65 percent for incomes above $1,000,000. As a result, the richest 22 percent of American taxpayers paid 96 percent of individual income taxes. Businesses faced a series of new taxes, especially on "excess profits" ranging from 20 percent to 80 percent on profits above pre-war levels. There were also excise taxes that everyone paid who purchased an automobile, jewelry, camera, or a motorboat.

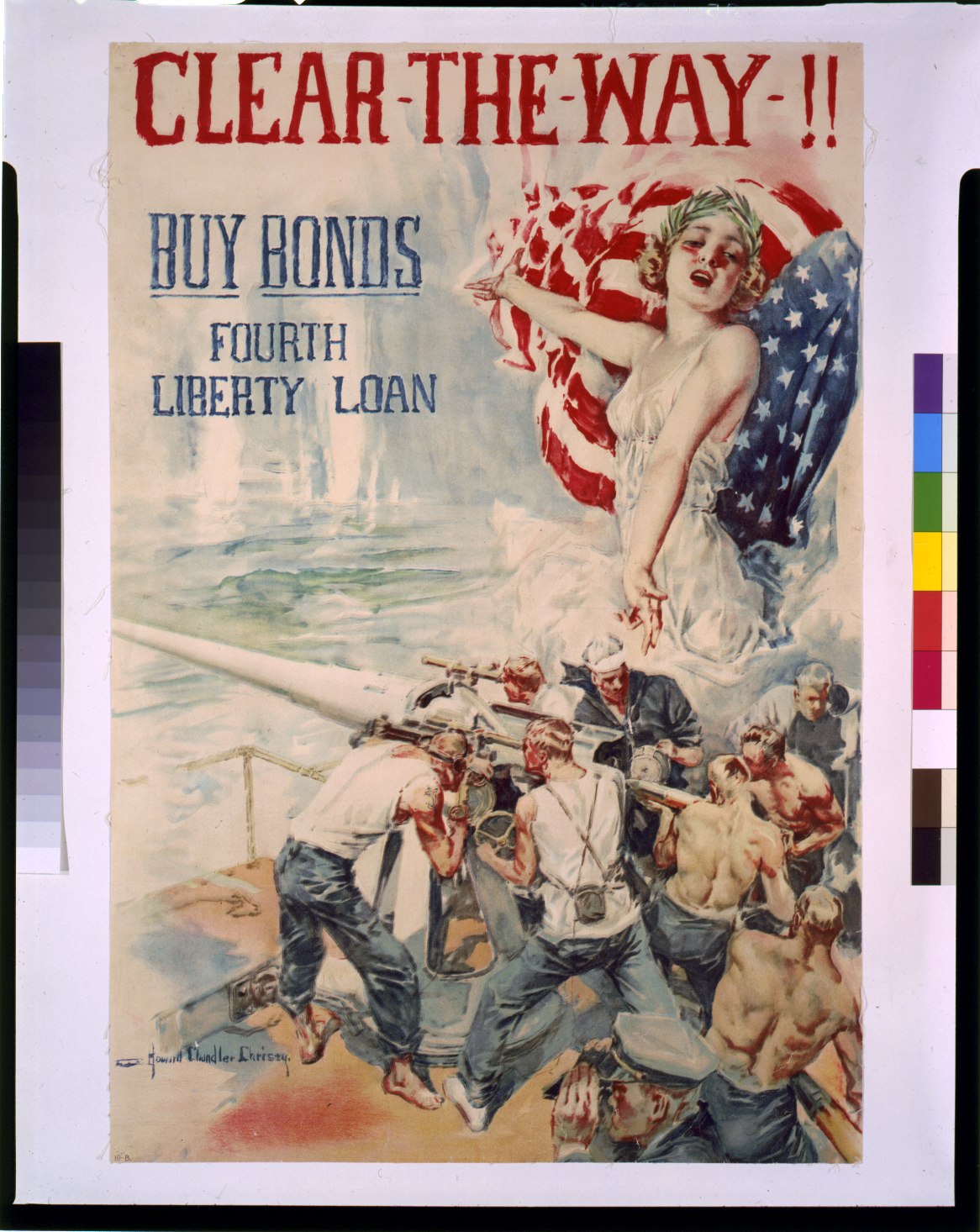

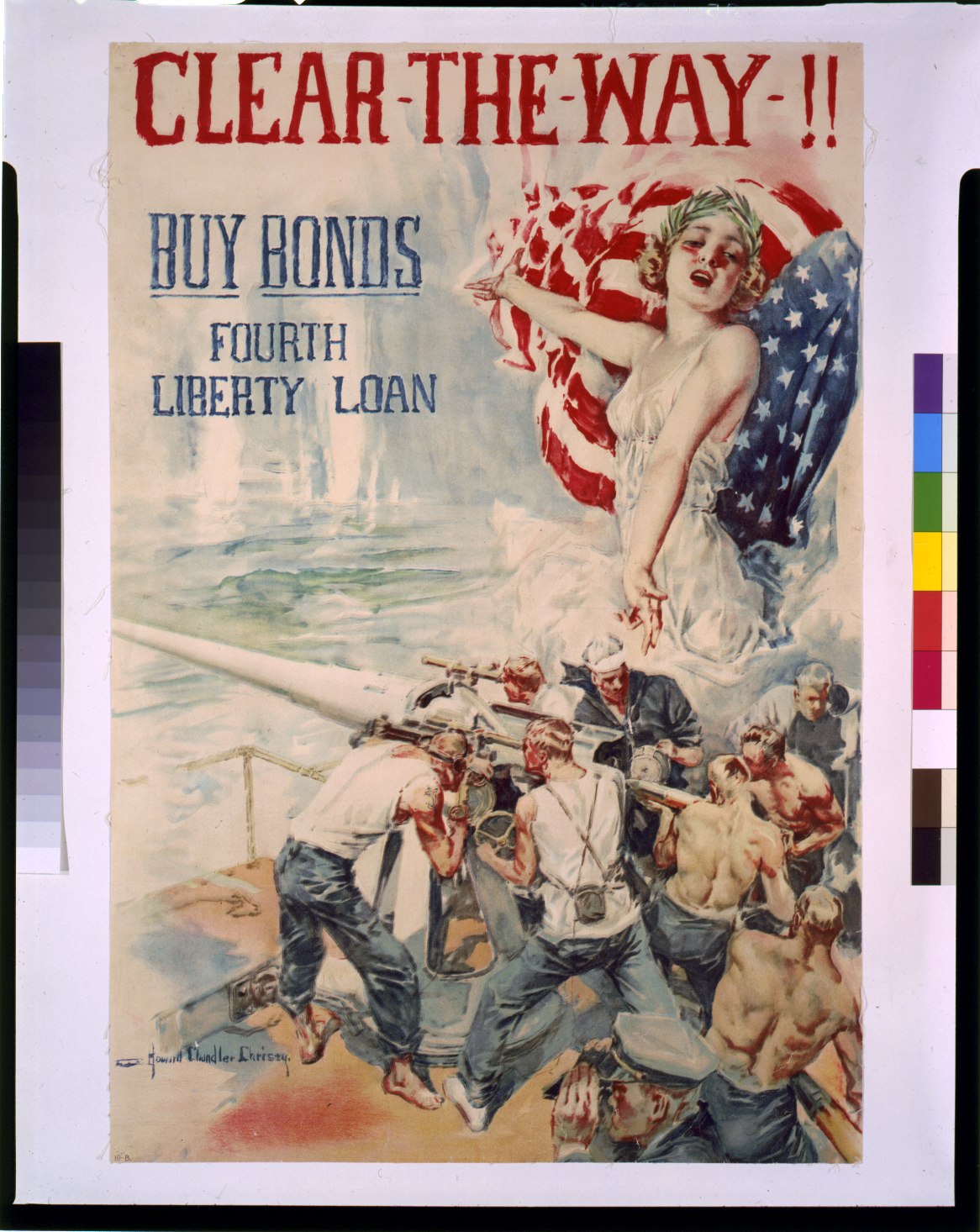

The greatest source of revenue came from war bonds, which were effectively merchandised to the masses through an elaborate innovative campaign to reach average Americans. Movie stars and other celebrities, supported by millions of posters, and an army of Four-Minute Men speakers explained the importance of buying bonds. In the third Liberty Loan campaign of 1918, more than half of all families subscribed. In total, $21 billion in bonds were sold with interest from 3.5 to 4.7 percent. The new Federal Reserve system encouraged banks to loan families money to buy bonds. All the bonds were redeemed, with interest, after the war. Before the United States entered the war, New York banks had loaned heavily to the British. After the U.S. entered in April 1917, the Treasury made $10 billion in long-term loans to Britain, France and the other allies, with the expectation the loans would be repaid after the war. Indeed, the United States insisted on repayment, which by the 1950s eventually was achieved by every country except Russia.

Labor

TheAmerican Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutua ...

(AFL) and affiliated trade unions were strong supporters of the war effort. Fear of disruptions to war production by labor radicals provided the AFL political leverage to gain recognition and mediation of labor disputes, often in favor of improvements for workers. They resisted strikes in favor of arbitration and wartime policy, and wages soared as near-full employment was reached at the height of the war. The AFL unions strongly encouraged young men to enlist in the military, and fiercely opposed efforts to reduce recruiting and slow war production by pacifists, the anti-war Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines general ...

(IWW) and radical socialists. To keep factories running smoothly, Wilson established the National War Labor Board in 1918, which forced management to negotiate with existing unions. Wilson also appointed AFL president Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers (; January 27, 1850December 13, 1924) was a British-born American cigar maker, labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and served as the organization's ...

to the powerful Council of National Defense

The Council of National Defense was a United States organization formed during World War I to coordinate resources and industry in support of the war effort, including the coordination of transportation, industrial and farm production, financial ...

, where he set up the War Committee on Labor.

After initially resisting taking a stance, the IWW became actively anti-war, engaging in strikes and speeches and suffering both legal and illegal suppression by federal and local governments as well as pro-war vigilantes. The IWW was branded as anarchic, socialist, unpatriotic, alien and funded by German gold, and violent attacks on members and offices would continue into the 1920s.

Women's roles

World War I saw women taking traditionally men's jobs in large numbers for the first time in

World War I saw women taking traditionally men's jobs in large numbers for the first time in American history

The history of the lands that became the United States began with the arrival of the first people in the Americas around 15,000 BC. Numerous indigenous cultures formed, and many saw transformations in the 16th century away from more densel ...

. Many women worked on the assembly line

An assembly line is a manufacturing process (often called a ''progressive assembly'') in which parts (usually interchangeable parts) are added as the semi-finished assembly moves from workstation to workstation where the parts are added in se ...

s of factories, assembling munitions. Some department stores employed African American women as elevator operators and cafeteria waitresses for the first time.

Most women remained housewives. The Food Administration helped housewives prepare more nutritious meals with less waste and with optimum use of the foods available. Most important, the morale of the women remained high, as millions of middle class women joined the Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

as volunteers to help soldiers and their families. With rare exceptions, women did not try to block the draft.

The Department of Labor created a Women in Industry group, headed by prominent labor researcher and social scientist Mary van Kleeck.Biographical/Historical - Mary van Kleeck. ''findingaids.smith.edu''. Smith College Special Collections. Retrieved 2019-09-05. This group helped develop standards for women who were working in industries connected to the war alongside the War Labor Policies Board, of which van Kleeck was also a member. After the war, the Women in Industry Service group developed into the U.S. Women's Bureau, headed by Mary Anderson.

Propaganda

Crucial to U.S. participation was the sweeping domestic propaganda campaign. In order to achieve this, President Wilson created theCommittee on Public Information

The Committee on Public Information (1917–1919), also known as the CPI or the Creel Committee, was an independent agency of the government of the United States under the Wilson administration created to influence public opinion to support the ...

through Executive Order 2594 on April 13, 1917, which was the first state bureau in the United States that's main focus was on propaganda. The man charged by President Wilson with organizing and leading the CPI was George Creel, a once relentless journalist and political campaign organizer who would search without mercy for any bit of information that would paint a bad picture on his opponents. Creel went about his task with boundless energy. He was able to create an intricate, unprecedented propaganda system that plucked and instilled an influence on almost all phases of normal American life. In the press—as well as through photographs, movies, public meetings, and rallies—the CPI was able to douse the public with Propaganda that brought on American patriotism whilst creating an anti-German image into the young populace, further quieting the voice of the neutrality supporters. It also took control of market regarding the dissemination of war-related information on the American home front, which in turn promoted a system of voluntary censorship in the country's newspapers and magazines while simultaneously policing these same media outlets for seditious content or anti-American support. The campaign consisted of tens of thousands of government-selected community leaders giving brief carefully scripted pro-war speeches at thousands of public gatherings.

Alongside government agencies were officially approved private vigilante groups like the American Protective League. They closely monitored (and sometimes harassed) people opposed to American entry into the war or displaying too much German heritage.

Other forms of propaganda included newsreels

A newsreel is a form of short documentary film, containing news stories and items of topical interest, that was prevalent between the 1910s and the mid 1970s. Typically presented in a cinema, newsreels were a source of current affairs, inform ...

, large-print posters (designed by several well-known illustrators of the day, including Louis D. Fancher

Louis Delton Fancher (December 25, 1884 – March 2, 1944) was an American artist and illustrator, notable for his drawings that appeared in books, in magazines, and on propaganda posters during World War I.Hughes, Edan Milton. ''Artists in Calif ...

and Henry Reuterdahl

Henry Reuterdahl (August 12, 1870 – December 21, 1925) was a Swedish-American painter highly acclaimed for his nautical artwork. He had a long relationship with the United States Navy.

In addition to serving as a Lieutenant Commander in the ...

), magazine and newspaper articles, and billboards. At the end of the war in 1918, after the Armistice was signed, the CPI was disbanded after inventing some of the tactics used by propagandists today.

Children

The nation placed a great importance on the role of children, teaching them patriotism and national service and asking them to encourage war support and educate the public about the importance of the war. TheBoy Scouts of America

The Boy Scouts of America (BSA, colloquially the Boy Scouts) is one of the largest scouting organizations and one of the largest youth organizations in the United States, with about 1.2 million youth participants. The BSA was founded in ...

helped distribute war pamphlets, helped sell war bonds, and helped to drive nationalism and support for the war.

Motor vehicles

Before the American entry into the war, many American-made heavyfour-wheel drive

Four-wheel drive, also called 4×4 ("four by four") or 4WD, refers to a two-axled vehicle drivetrain capable of providing torque to all of its wheels simultaneously. It may be full-time or on-demand, and is typically linked via a transfer ca ...

trucks, notably made by Four Wheel Drive

Four-wheel drive, also called 4×4 ("four by four") or 4WD, refers to a two-axled vehicle drivetrain capable of providing torque to all of its wheels simultaneously. It may be full-time or on-demand, and is typically linked via a transfer cas ...

(FWD) Auto Company, and Jeffery / Nash Quads, were already serving in foreign militaries, bought by Great Britain, France and Russia. When the war started, motor vehicles had begun to replace horses and pulled wagons, but on the European muddy roads and battlefields, two-wheel drive trucks got stuck all the time, and the leading allied countries could not produce 4WD trucks in the numbers they needed. The U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

wanted to replace four-mule

The mule is a domestic equine hybrid between a donkey and a horse. It is the offspring of a male donkey (a jack) and a female horse (a mare). The horse and the donkey are different species, with different numbers of chromosomes; of the two po ...

teams used for hauling standard 1 U.S. ton (3000 lb / 1.36 metric ton

The tonne ( or ; symbol: t) is a unit of mass equal to 1000 kilograms. It is a non-SI unit accepted for use with SI. It is also referred to as a metric ton to distinguish it from the non-metric units of the short ton (United States ...

) loads with trucks, and requested proposals from companies in late 1912. This led the Thomas B. Jeffery Company

The Thomas B. Jeffery Company was an American automobile manufacturer in Kenosha, Wisconsin, from 1902 until 1916. The company manufactured the Rambler and Jeffery brand motorcars. It was preceded by the Gormully & Jeffery Manufacturing Compa ...

to develop a competent four-wheel drive, 1 short ton capacity truck by July 1913: the "Quad".

U.S. Marines riding in a Jeffery Quad, Fort Santo Domingo, c. 1916

The Jeffery Quad truck, and from the company's take-over by Nash Motors

Nash Motors Company was an American automobile manufacturer based in Kenosha, Wisconsin from 1916 to 1937. From 1937 to 1954, Nash Motors was the automotive division of the Nash-Kelvinator Corporation. Nash production continued from 1954 to 1 ...

after 1916, the ''Nash'' Quad, greatly assisted the World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

efforts of several Allied nations, particularly the French. The U.S. first adopted Quads in anger in the USMC's occupations of Haiti, and the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares with ...

, from 1915 through 1917, as well as in the 1916 Pancho Villa Expedition

The Pancho Villa Expedition—now known officially in the United States as the Mexican Expedition, but originally referred to as the "Punitive Expedition, U.S. Army"—was a military operation conducted by the United States Army against the p ...

against Mexico.

Once the U.S. entered World War I, general John Pershing

General of the Armies John Joseph Pershing (September 13, 1860 – July 15, 1948), nicknamed "Black Jack", was a senior United States Army officer. He served most famously as the commander of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) on the Wes ...

used Nash Quads heavily in the European campaigns. They became the workhorse of the Allied Expeditionary Force there — both as regular transport trucks, and in the form of the Jeffery armored car

The Jeffery armored car was an armored car developed by the US and Canada. It saw heavy use in World War I.

Armored Car No. 1

The Jeffery Armored Car No.1 was developed by the Thomas B. Jeffery Company in Kenosha, Wisconsin in 1915 with a hull fr ...

. Some 11,500 Jeffery / Nash Quads were built between 1913 and 1919.

The success of the ''Four Wheel Drive'' cars in early military tests had prompted the U.S. company to switch from cars to truck manufacturing. For World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, the U.S. Army ordered an amount of 15,000 FWD Model B