Union of the Russian People on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Union of the Russian People (URP) (russian: Союз русского народа, translit=Soyuz russkogo naroda; СРН/SRN) is a

By 1906 the Union had a total of 300,000 members spread over 1,000 different branches. Most of their supporters came from the social stratum which 'had either lost – or were afraid of losing – their petty status' in society as a result of reform and modernisation – much like the supporters of fascism – among them urbanised peasants working as labourers, policemen and other low-ranking state officials who risked losing their power, and small shopkeepers and artisans who were losing the competition against big business and industry. By 1907 it is said about up to 900 local URP branches existed in many cities, towns and even villages. Apart from the ones named above, the largest were in

By 1906 the Union had a total of 300,000 members spread over 1,000 different branches. Most of their supporters came from the social stratum which 'had either lost – or were afraid of losing – their petty status' in society as a result of reform and modernisation – much like the supporters of fascism – among them urbanised peasants working as labourers, policemen and other low-ranking state officials who risked losing their power, and small shopkeepers and artisans who were losing the competition against big business and industry. By 1907 it is said about up to 900 local URP branches existed in many cities, towns and even villages. Apart from the ones named above, the largest were in

Союз Русского Народа. The first chairman of the refounded group was Vyacheslav Klykov. The Union's main activities can be described as national patriotism with a strong emphasis on theЧВК и террористы на службе УПЦ МП. Часть 2: Сумская епархия

argumentua.com. 2017-09-08

Programme and Statute of the Union of the Russian People

{{Authority control 1905 establishments in the Russian Empire 1917 disestablishments in Russia Antisemitism in the Russian Empire Conservative parties in Russia Defunct nationalist parties in Russia Eastern Orthodoxy and far-right politics Far-right political parties in Russia Monarchist parties in Russia Political parties disestablished in 1917 Political parties established in 1905 Political parties in the Russian Empire Political parties of the Russian Revolution Russian nationalist organizations Defunct conservative parties National conservative parties Social conservative parties Eastern Orthodox political parties Anti-communist parties Right-wing parties in Europe Defunct far-right parties

loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British C ...

far-right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

political party

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific ideological or p ...

, the most important among Black-Hundredist monarchist

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalis ...

political organizations in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

between 1905 and 1917. — p. 71–72. Since 2000s organizational cells of the Union are being revived in Russia as well as Ukraine (Union of the Russian People (2005)

The Union of the Russian People (URP or SRN; russian: Союз русского народа; СРН; ''Soyuz russkogo naroda'', ''SRN'') — is a modern Russian Orthodox-monarchical organization, recreated in 2005 on the basis of the ideology of ...

).

Founded in October 1905, its aim was to rally the people behind 'Great Russian nationalism

Great Russia, sometimes Great Rus' (russian: Великая Русь, , , , , ), is a name formerly applied to the territories of "Russia proper", the land that formed the core of Muscovy and later Russia. This was the land to which the eth ...

' and the Tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East and South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" in the European medieval sense of the ter ...

, espousing anti-socialist, anti-liberal, and above all antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Ant ...

views. By 1906 it had over 300,000 members. Its paramilitary armed bands, called the Black Hundreds

The Black Hundred (russian: Чёрная сотня, translit=Chornaya sotnya), also known as the black-hundredists (russian: черносотенцы; chernosotentsy), was a reactionary, monarchist and ultra-nationalist movement in Russia in t ...

, fought revolutionaries violently in the streets. Its leaders organised a series of political assassinations of deputies and other representatives of parties which supported the Russian Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

.

The Union was dissolved in 1917 in the wake of the Revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

, and its leader, Alexander Dubrovin

Alexander Ivanovich Dubrovin (russian: Алекса́ндр Ива́нович Дубро́вин) (1855, Kungur – unknown) was a Russian Empire right wing politician, a leader of the Union of the Russian People (URP).

Biography

A trained do ...

placed under arrest.

Some modern academic researchers view the Union of the Russian People as an early example of fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and t ...

.Rogger

Ideology and political views

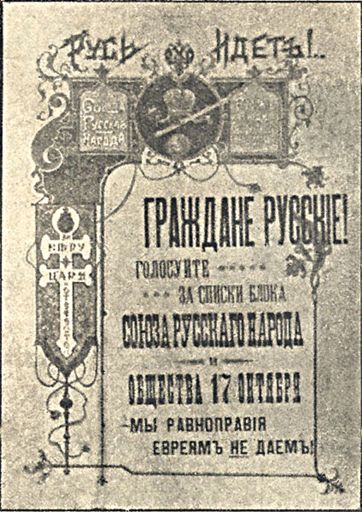

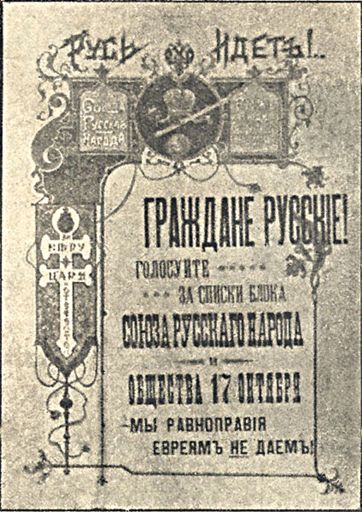

The Union was the leading exponent of antisemitism in the wake of the 1905 Revolution.Figes, p. 245 It has been described as 'an early Russian version of theFascist movement

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

', as it was anti-socialist, anti-liberal, and 'above all anti-Semitic'.

The Union of the Russian People called for the 'restoration of the popular autocracy', a concept they believed had existed before Russia had been taken over by 'intellectuals

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the reality of society, and who proposes solutions for the normative problems of society. Coming from the world of culture, either as a creator or ...

and Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

'. Antisemitism was brought into the URP by what became the organisation's ideological core, chairman Alexander Dubrovin

Alexander Ivanovich Dubrovin (russian: Алекса́ндр Ива́нович Дубро́вин) (1855, Kungur – unknown) was a Russian Empire right wing politician, a leader of the Union of the Russian People (URP).

Biography

A trained do ...

, Vladimir Purishkevich, Pavel Krushevan

Pavel Aleksandrovich Krushevan (russian: Павел Александрович Крушеван; ro, Pavel Crușeveanu) ( – ) was a journalist, editor, publisher and an official in Imperial Russia. He was an active Black Hundredist and was kn ...

, Pavel Bulatsel and some other 'radical temperament anti-Semitic rabble- rousers', who had seceded from the Russian Assembly

The Russian Assembly (russian: link=no, Русское собрание) was a Russian loyalist, right-wing, monarchist political group (party). It was founded in Saint Petersburg in October−November 1900, and dismissed in 1917. It was led by P ...

.Rogger, p. 191–3 The methods of the Union were not what the Russian Assembly considered proper conduct. Save lawyer and journalist Bulatsel, another leading intellectual of the URP was B. V. Nikolsky, ''privatdozent

''Privatdozent'' (for men) or ''Privatdozentin'' (for women), abbreviated PD, P.D. or Priv.-Doz., is an academic title conferred at some European universities, especially in German-speaking countries, to someone who holds certain formal qualific ...

'' (senior lecturer

Senior lecturer is an academic rank. In the United Kingdom, Ireland, New Zealand, Australia, Switzerland, and Israel senior lecturer is a faculty position at a university or similar institution. The position is tenured (in systems with this conce ...

) at Petersburg University.Rogger, p. 204

The Union was above all a movement of 'Great Russian nationalism

Great Russia, sometimes Great Rus' (russian: Великая Русь, , , , , ), is a name formerly applied to the territories of "Russia proper", the land that formed the core of Muscovy and later Russia. This was the land to which the eth ...

'.Figes, p. 246 Its very first aim it had declared to be a 'Great Russia, United and Indivisible'. Its nationalism was based on xenophobia

Xenophobia () is the fear or dislike of anything which is perceived as being foreign or strange. It is an expression of perceived conflict between an in-group and out-group and may manifest in suspicion by the one of the other's activities, a ...

and racism.

The Union also actively campaigned against Ukrainian self-determination and in particular, against the 'cult

In modern English, ''cult'' is usually a pejorative term for a social group that is defined by its unusual religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs and rituals, or its common interest in a particular personality, object, or goal. Thi ...

' of the popular Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko

Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko ( uk, Тарас Григорович Шевченко , pronounced without the middle name; – ), also known as Kobzar Taras, or simply Kobzar (a kobzar is a bard in Ukrainian culture), was a Ukrainian poet, wr ...

.

History

Creation

The Union of the Russian people was by far the most important of the extreme rightist groups formed in the wake of the 1905 Revolution.Figes, p. 196 It was founded in October 1905 as a movement to mobilise and rally the masses against the Left, by the two 'minor government officials'Alexander Dubrovin

Alexander Ivanovich Dubrovin (russian: Алекса́ндр Ива́нович Дубро́вин) (1855, Kungur – unknown) was a Russian Empire right wing politician, a leader of the Union of the Russian People (URP).

Biography

A trained do ...

and Vladimir Purishkevich. The idea to create the union originated between several public figures of Russia who entered its political arena before the 1905 Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

.

1905–06

Five days after the proclamation of the October Manifesto on , Purishkevich, Apollo Apollonovich Maikov (son of poetApollon Maykov

Apollon Nikolayevich Maykov (russian: Аполло́н Никола́евич Ма́йков, , Moscow – , Saint Petersburg) was a Russian poet, best known for his lyric verse showcasing images of Russian villages, nature, and history. His love ...

), Pavel Bulatzel

Pavel ( Bulgarian, Russian, Serbian and Macedonian: Павел, Czech, Slovene, Romanian: Pavel, Polish: Paweł, Ukrainian: Павло, Pavlo) is a male given name. It is a Slavic cognate of the name Paul (derived from the Greek Pavlos). Pav ...

, Baranov, Vladimir Gringmut

Vladimir may refer to:

Names

* Vladimir (name) for the Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Macedonian, Romanian, Russian, Serbian, Slovak and Slovenian spellings of a Slavic name

* Uladzimir for the Belarusian version of the name

* Volodymyr for the Ukra ...

and some others gathered at Dubrovin's home. At this meeting, they concurred with Dubrovin's idea to set up a political organization (Dubrovin opposed to calling it a party). In a couple of weeks initiators worked out an organisational structure, devised a program, and on formally announced the founding of the Union of the Russian People. Dubrovin was elected its chairman.

The Union's Manifesto expressed a 'plebeian mistrust' of every political party, as well as the bureaucracy and the intelligentsia. The group looked at these as obstacles to 'the direct communion between the Tsar and his people'. This struck a deep chord with Nicholas II, who also shared the deep belief in re-establishment of autocratic personal rule, as had existed in the Muscovite state of the 1600s. It also stood for the russification of non-Russian citizens. The charter was adopted in August 1906.

Support

After the1905 Revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

the Orthodox Church

Orthodox Church may refer to:

* Eastern Orthodox Church

* Oriental Orthodox Churches

* Orthodox Presbyterian Church

* Orthodox Presbyterian Church of New Zealand

* State church of the Roman Empire

* True Orthodox church

See also

* Orthodox (d ...

's conservative clergy members allied with extreme Rightist organisations, the Union of the Russian People being one of them, in opposing the liberals' further attempts at a church reform and extension of religious freedom and toleration. Several prominent, leading church members were also supportive of the organisation, among them the royal family's close friend and future Orthodox Saint John of Kronstadt

John of Kronstadt or John Iliytch Sergieff ( pre-reform Russian: ; post-reform russian: Иоа́нн Кроншта́дтский; 1829 – ) was a Russian Orthodox archpriest and a member of the Most Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church. ...

, Iliodor the monk, and Bishop Hermogenes. Each local department of the Union of the Russian People had its own horugvs and icons, which were kept in local cathedrals or monasteries. The opening of the departments of the Union of the Russian People was always accompanied by solemn prayer services, which were served by local bishops, in the person of the latter, the Russian Church gave its official blessing to the Union of the Russian People and recommended the latter to its clerics. In fact, into the orbit of the Union of the Russian People the entire episcopate was involved. It also had support from leading members of the court and government, one of the supporters being the Minister of the Interior

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

Nikolay Maklakov

Nikolay Alexeyevich Maklakov (9 September 1871 – 5 September 1918) (N.S.) was a Chamberlain of the Imperial court, a Russian monarchist, and a prominent right-wing statesman. He was a governor in the Ukrain and state councillor who served as ...

.

Tsar Nicholas II was highly supportive of the Union and patronised it: he wore the badge of the Union, and wished the Union and its leaders 'total success' in their efforts to unite what he called 'loyal Russians' in defence of the autocracy. The Tsar also gave orders to provide funds for the Union, and the Ministry of the Interior complied by funding the Union's newspapers, and also providing them with weapons through secret channels. Dubrovin was also in contact with senior officials and the secret services of Russia. Minister of the Interior Pyotr Durnovo

The House of Durnovo (russian: Дурново) (known variant 'Durnovy' lural 'Durnov' ,'Durnova' (russian: 'Дурновы'; 'Дурнов', 'Дурнова')) is a prominent family of Russian nobility. Durnovo is one of two Russian noble famili ...

was completely in the know about the foundation of the Union while his subordinates actively worked upon creation of an open organisation to counteract the influence of revolutionaries and liberals among the masses. Around the same the head of the political section of gendarmes department Pyotr Rachkovsky

Pyotr Ivanovich Rachkovsky (russian: Пётр Иванович Рачковский; 1853 – 1 November 1910) was chief of Okhrana, the secret service in Imperial Russia. He was based in Paris from 1885 to 1902.

Activities in 1880s–1890s

Afte ...

reported his chief, Colonel (later General) about such attempts and proposed Gerasimov to introduce him to Dubrovin. Their meeting took place in late October 1905 in the apartment of Rachkovsky.

With powerful administrative support and funding at their disposal, the Union of the Russian People managed to organise and conduct its first mass public event less than a fortnight

A fortnight is a unit of time equal to 14 days (two weeks). The word derives from the Old English term , meaning "" (or "fourteen days," since the Anglo-Saxons counted by nights).

Astronomy and tides

In astronomy, a ''lunar fortnight'' is ha ...

after its creation. The first public rally of the URP, with about 2,000 attendance, was held on in Mikhailovsky Manege

Michael Manege (''Mikhailovsky manezh''; russian: Михайловский манеж) is the Neoclassical building of an early 19th-century riding academy in the historic center of Saint Petersburg, Russia. It was converted into an indoor spor ...

, a popular venue in Petersburg. An orchestra was playing, a church choir sang "Praise God" and "Tsar Divine"; leaders of the URP (Dubrovin, Purishkevich, Bulatsel, Nikolsky) addressed the mob from a rostrum erected in the centre of the arena. Special guests from the "Russian Assembly

The Russian Assembly (russian: link=no, Русское собрание) was a Russian loyalist, right-wing, monarchist political group (party). It was founded in Saint Petersburg in October−November 1900, and dismissed in 1917. It was led by P ...

": Prince M. N. Volkonsky, journalist from ''Novoye Vremya

''The New Times'' (russian: Новое Время) is a Russian language magazine in Russia. The magazine was founded in 1943. The current version, established in 1988, is a liberal, independent Russian weekly news magazine, publishing for Ru ...

'' Nikolai Engelhardt and two bishops also welcomed the new party with their speeches.

Members of the Tsar's court, like Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolayevich, Alexander Trepov

Alexander Fyodorovich Trepov (; 30 September 1862, Kiev – 10 November 1928, Nice) was the Prime Minister of the Russian Empire from 23 November 1916 until 9 January 1917. He was conservative, a monarchist, a member of the Russian Assembly, a ...

, and other government officials and clergy members 'unquestionably welcomed a movement such as this'. Sergei Witte

Count Sergei Yulyevich Witte (; ), also known as Sergius Witte, was a Russian statesman who served as the first prime minister of the Russian Empire, replacing the tsar as head of the government. Neither a liberal nor a conservative, he attract ...

was a rare occasion among high-ranking officials being 'unequivocally hostile to the URP' (in his memoirs he calls Dubrovin a 'high-handed and abusive leader').

Street fighting

The Union was horrified by Tsar Nicholas II's refusal to strike down harshly on the Leftist revolutionaries. The Union, therefore, decided to organise this for the Tsar, and organised paramilitary bands, which came to be known as the 'Black Hundreds

The Black Hundred (russian: Чёрная сотня, translit=Chornaya sotnya), also known as the black-hundredists (russian: черносотенцы; chernosotentsy), was a reactionary, monarchist and ultra-nationalist movement in Russia in t ...

' by the democrats, to fight revolutionaries in the streets. These militant groups marched through the streets holding in their pockets knives and brass knuckles, and carrying religious symbols such as icons and crosses and imperial ones such as patriotic banners and portraits of Tsar Nicholas II. They marched through the streets fighting to 'revenge themselves' and restore the old hierarchy of society and races. Their numbers were swelled by thousands of criminals who had been released as a part of the October amnesty, who looked at it as a chance of violence and pillaging. Often encouraged by police officers, they beat up suspected democratic sympathisers, making them kneel before tsarist portraits or making them kiss the Imperial flag. In October 1906, they formed a Black-Hundredist organisation called Russian People United (russian: Объединённый русский народ, translit=Ob’yedinyonniy russkiy narod).

1906–1917

By 1906 the Union had a total of 300,000 members spread over 1,000 different branches. Most of their supporters came from the social stratum which 'had either lost – or were afraid of losing – their petty status' in society as a result of reform and modernisation – much like the supporters of fascism – among them urbanised peasants working as labourers, policemen and other low-ranking state officials who risked losing their power, and small shopkeepers and artisans who were losing the competition against big business and industry. By 1907 it is said about up to 900 local URP branches existed in many cities, towns and even villages. Apart from the ones named above, the largest were in

By 1906 the Union had a total of 300,000 members spread over 1,000 different branches. Most of their supporters came from the social stratum which 'had either lost – or were afraid of losing – their petty status' in society as a result of reform and modernisation – much like the supporters of fascism – among them urbanised peasants working as labourers, policemen and other low-ranking state officials who risked losing their power, and small shopkeepers and artisans who were losing the competition against big business and industry. By 1907 it is said about up to 900 local URP branches existed in many cities, towns and even villages. Apart from the ones named above, the largest were in Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

, Saratov

Saratov (, ; rus, Сара́тов, a=Ru-Saratov.ogg, p=sɐˈratəf) is the largest city and administrative center of Saratov Oblast, Russia, and a major port on the Volga River upstream (north) of Volgograd. Saratov had a population of 901, ...

and Astrakhan

Astrakhan ( rus, Астрахань, p=ˈastrəxənʲ) is the largest city and administrative centre of Astrakhan Oblast in Southern Russia. The city lies on two banks of the Volga, in the upper part of the Volga Delta, on eleven islands of the ...

; Volhynian Governorate

Volhynian Governorate or Volyn Governorate (russian: Волы́нская губе́рния, translit=Volynskaja gubernija, uk, Волинська губернія, translit=Volynska huberniia) was an administrative-territorial unit initially ...

is also mentioned among the largest by the representation of the URP.

The Union opposed Stolypin's reforms, being supporters of the 'legitimist bloc' which, through its support in the court, church, nobility and the Union, defeated nearly all of Stolypin's reform proposals.

The Union also became the main instigator (through meetings, gatherings, lectures, manifestations and mass public prayers) of the pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russian ...

s against Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

(especially in 1906 in Gomel

Gomel (russian: Гомель, ) or Homiel ( be, Гомель, ) is the administrative centre of Gomel Region and the second-largest city in Belarus with 526,872 inhabitants (2015 census).

Etymology

There are at least six narratives of the o ...

, Yalta

Yalta (: Я́лта) is a resort city on the south coast of the Crimean Peninsula surrounded by the Black Sea. It serves as the administrative center of Yalta Municipality, one of the regions within Crimea. Yalta, along with the rest of Cri ...

, Białystok

Białystok is the largest city in northeastern Poland and the capital of the Podlaskie Voivodeship. It is the tenth-largest city in Poland, second in terms of population density, and thirteenth in area.

Białystok is located in the Białystok U ...

, Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

, Sedlets and other cities), in which members of the URP often took an active part. In the wake of the Beiliss Affair, Nicholas II used the large wave of antisemitism in the population, spread and rallied by groups such as the Union of the Russian People, to rally support for his regime. It was one of the first to extreme Rightist groups which had proclaimed a charge of ritual murder in the so-called Beiliss Affair

Menahem Mendel Beilis (sometimes spelled Beiliss; yi, מנחם מענדל בייליס, russian: Менахем Мендель Бейлис; 1874 – 7 July 1934) was a Russian Jew accused of ritual murder in Kiev in the Russian Empire in a not ...

, and supported the anti-Semitic persecution throughout the trial of Menahem Beiliss.

In 1908 URP members of the clergy claimed through a petition the right to carry weapons

The right to keep and bear arms (often referred to as the right to bear arms) is a right for people to possess weapons (arms) for the preservation of life, liberty, and property. The purpose of gun rights is for self-defense, including securi ...

; this petition, however, was denied.

In 1908–10, the infighting in the URP broke the organisation into several smaller entities, which were in constant conflict with each other: Union of Archangel Michael (russian: Союз Михаила Архангела, translit=Soyuz Mikhaila Arkhangela), Union of the Russian People (russian: Союз русского народа, translit=Soyuz russkogo naroda), Dubrovin's All-Russian Union of the Russian People in Petersburg (russian: Всероссийский дубровинский Союз русского народа в Петербурге, translit=Vserossiysky dubrovinsky Soyuz russkogo naroda v Peterburge), etc. After the February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and some ...

of 1917, all of the Black-Hundredist organisations were forcefully dissolved and banned.

Soon after the February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and some ...

of 1917, the URP was suspended and its leader Alexander Dubrovin

Alexander Ivanovich Dubrovin (russian: Алекса́ндр Ива́нович Дубро́вин) (1855, Kungur – unknown) was a Russian Empire right wing politician, a leader of the Union of the Russian People (URP).

Biography

A trained do ...

was arrested.

Party leaders and organisation

The supreme body of URP was called the Main Council (russian: Главный Совет, translit=Glavny Soviet). Its chairmanAlexander Dubrovin

Alexander Ivanovich Dubrovin (russian: Алекса́ндр Ива́нович Дубро́вин) (1855, Kungur – unknown) was a Russian Empire right wing politician, a leader of the Union of the Russian People (URP).

Biography

A trained do ...

had two deputies: noble landowner and future Duma Deputy Vladimir Purishkevich and engineer A. I. Trishatny. From six other board members (Pavel Bulatzel, George Butmi, P. P. Surin and others) four belonged to the merchant estate, and two were peasants by origin. A merchant from Petersburg I. I. Baranov was the treasurer

A treasurer is the person responsible for running the treasury of an organization. The significant core functions of a corporate treasurer include cash and liquidity management, risk management, and corporate finance.

Government

The treasury ...

of the URP, and barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include taking cases in superior courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, researching law and givin ...

Sergei Trishatny (elder brother of a Deputy Chairman) performed as secretary.

Later the Main Council increased to 12 members, among which S. D. Chekalov, M. N. Zelensky, Ye. D. Golubev, N. N. Yazykov, G. A. Slipak are mentioned.

Newspapers

URP's chiefnewspaper

A newspaper is a periodical publication containing written information about current events and is often typed in black ink with a white or gray background.

Newspapers can cover a wide variety of fields such as politics, business, spor ...

was ''Russkoe znamya

''Russkoye Znamya'' (russian: Русское знамя; ''Russian Banner'') was a newspaper, organ of the Union of the Russian People established in St. Petersburg by Alexander Dubrovin on , notoriously known for its antisemitic bias.

It was d ...

'' (Russian Banner), a newspaper which first published notorious "Protocols of the Elders of Zion". In provincial Russia ''The Pochayev Circular'' (russian: Pochayevsky listok) was the most popular of the URP newspapers. URP also printed its propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

materials in ''Moskovskiye Vedomosti

''Moskovskiye Vedomosti'' ( rus, Моско́вские ве́домости, p=mɐˈskofskʲɪje ˈvʲedəməsʲtʲɪ; ''Moscow News'') was Russia's largest newspaper by circulation before it was overtaken by Saint Petersburg dailies in the m ...

'' ("Moscow News"), ''Grazhdanin'' ("Citizen"), ''Kievlyanin'' ("Kievan") and others.

Modern revival and current activity

The Union of the Russian People has seen a revival in Russia since 2005 and has several followers and 17 offices in large cities.Link textСоюз Русского Народа. The first chairman of the refounded group was Vyacheslav Klykov. The Union's main activities can be described as national patriotism with a strong emphasis on the

Russian Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = ru

, image = Moscow July 2011-7a.jpg

, imagewidth =

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia

, abbreviation = ROC

, type ...

and revival of Russian traditions gone into the past after the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

.

The Union of the Russian People has also been noticed to exist in Ukraine since at least 2010.argumentua.com. 2017-09-08

See also

*Black Hundreds

The Black Hundred (russian: Чёрная сотня, translit=Chornaya sotnya), also known as the black-hundredists (russian: черносотенцы; chernosotentsy), was a reactionary, monarchist and ultra-nationalist movement in Russia in t ...

Bibliography

* * * * * * *References

External links

Programme and Statute of the Union of the Russian People

{{Authority control 1905 establishments in the Russian Empire 1917 disestablishments in Russia Antisemitism in the Russian Empire Conservative parties in Russia Defunct nationalist parties in Russia Eastern Orthodoxy and far-right politics Far-right political parties in Russia Monarchist parties in Russia Political parties disestablished in 1917 Political parties established in 1905 Political parties in the Russian Empire Political parties of the Russian Revolution Russian nationalist organizations Defunct conservative parties National conservative parties Social conservative parties Eastern Orthodox political parties Anti-communist parties Right-wing parties in Europe Defunct far-right parties