Unification of Bulgaria on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Unification of Bulgaria ( bg, Съединение на България, ''Saedinenie na Balgariya'') was the act of unification of the

The Unification of Bulgaria ( bg, Съединение на България, ''Saedinenie na Balgariya'') was the act of unification of the

In these conditions it was natural that Bulgarians in Bulgaria, Eastern Rumelia and Macedonia all strived for unity. The first attempt was made in 1880. The new British prime minister,

In these conditions it was natural that Bulgarians in Bulgaria, Eastern Rumelia and Macedonia all strived for unity. The first attempt was made in 1880. The new British prime minister,

Meanwhile, military manoeuvres were being carried out in the outskirts of Plovdiv. Major Danail Nikolaev, who was in charge of the manoeuvres, was aware of and supported the unionists. On , Rumelian militia (Eastern Rumelia's armed forces) and armed unionist groups entered Plovdiv and took over the Governor's residence.

The Governor Gavril Krastevich, was arrested by the rebels and paraded through the streets of Plovdiv before being expelled to Constantinople.

A temporary government was formed immediately, with Georgi Stranski at its head. Major Danail Nikolaev was appointed commander of armed forces. With help from Russian officers, he created the strategical plan for defence against the expected Ottoman intervention. Mobilization was declared in Eastern Rumelia.

As soon as it took power on , the temporary government sent a telegram, asking the knyaz to accept the Unification. On Alexander I answered with a special manifest. On the next day, accompanied by the prime minister Petko Karavelov and the head of Parliament

Meanwhile, military manoeuvres were being carried out in the outskirts of Plovdiv. Major Danail Nikolaev, who was in charge of the manoeuvres, was aware of and supported the unionists. On , Rumelian militia (Eastern Rumelia's armed forces) and armed unionist groups entered Plovdiv and took over the Governor's residence.

The Governor Gavril Krastevich, was arrested by the rebels and paraded through the streets of Plovdiv before being expelled to Constantinople.

A temporary government was formed immediately, with Georgi Stranski at its head. Major Danail Nikolaev was appointed commander of armed forces. With help from Russian officers, he created the strategical plan for defence against the expected Ottoman intervention. Mobilization was declared in Eastern Rumelia.

As soon as it took power on , the temporary government sent a telegram, asking the knyaz to accept the Unification. On Alexander I answered with a special manifest. On the next day, accompanied by the prime minister Petko Karavelov and the head of Parliament

After the Unification was already a fact, it took three days for Constantinople to become aware of what had actually happened. A new problem then arose: according to the Berlin treaty the Sultan was only allowed to send troops to Eastern Rumelia at the request of Eastern Rumelia's governor. Gavril Krastevich, the governor at the time, made no such request. At the same time the Ottoman Empire was advised in harsh tone both by London and St. Petersburg not to take any such actions and instead to wait for the decision of the international conference. The Ottomans did not attack Bulgaria, neither intervened in the

After the Unification was already a fact, it took three days for Constantinople to become aware of what had actually happened. A new problem then arose: according to the Berlin treaty the Sultan was only allowed to send troops to Eastern Rumelia at the request of Eastern Rumelia's governor. Gavril Krastevich, the governor at the time, made no such request. At the same time the Ottoman Empire was advised in harsh tone both by London and St. Petersburg not to take any such actions and instead to wait for the decision of the international conference. The Ottomans did not attack Bulgaria, neither intervened in the

Principality of Bulgaria

The Principality of Bulgaria ( bg, Княжество България, Knyazhestvo Balgariya) was a vassal state under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire. It was established by the Treaty of Berlin in 1878.

After the Russo-Turkish War end ...

and the province of Eastern Rumelia

Eastern Rumelia ( bg, Източна Румелия, Iztochna Rumeliya; ota, , Rumeli-i Şarkî; el, Ανατολική Ρωμυλία, Anatoliki Romylia) was an autonomous province (''oblast'' in Bulgarian, '' vilayet'' in Turkish) in the Ott ...

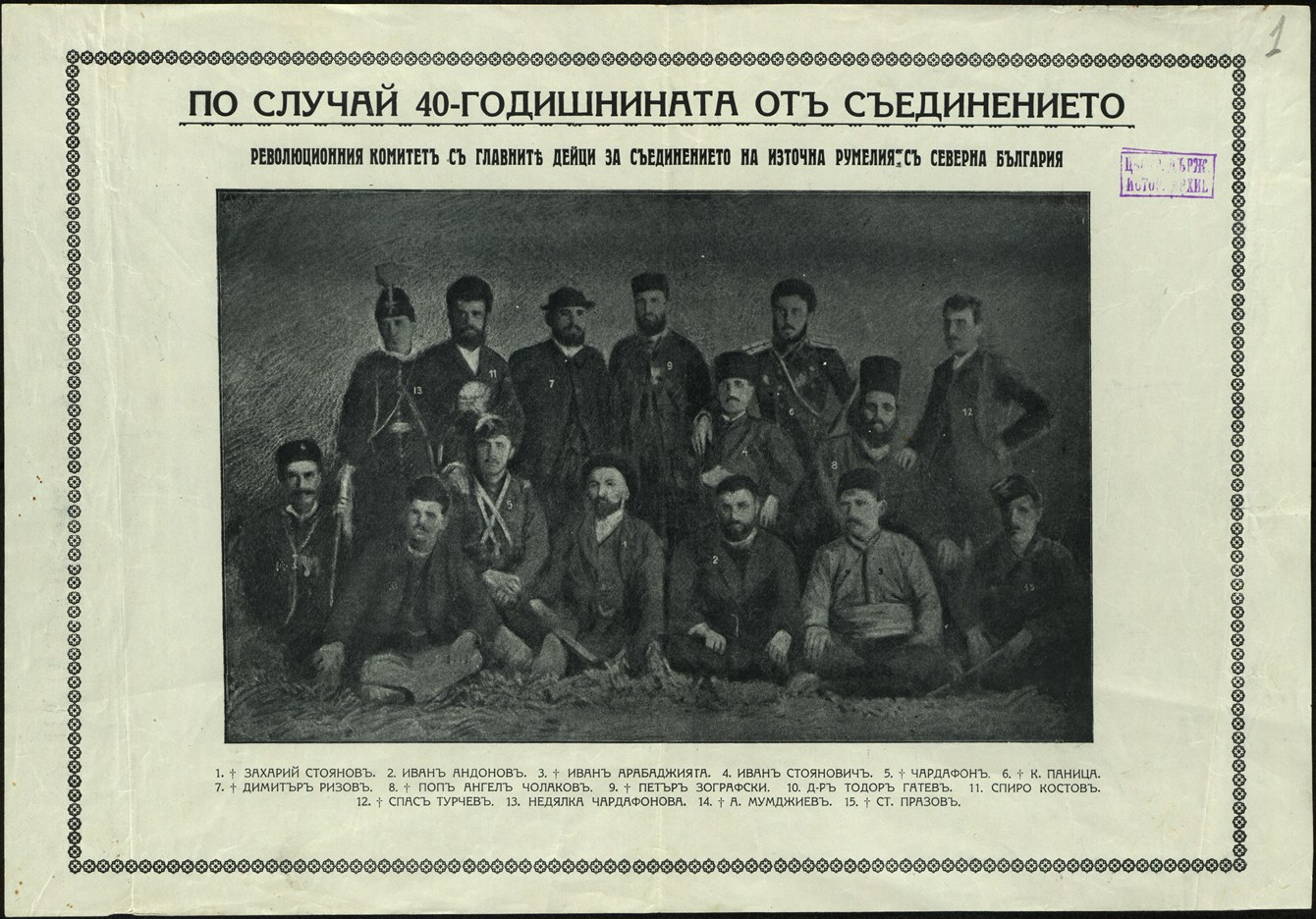

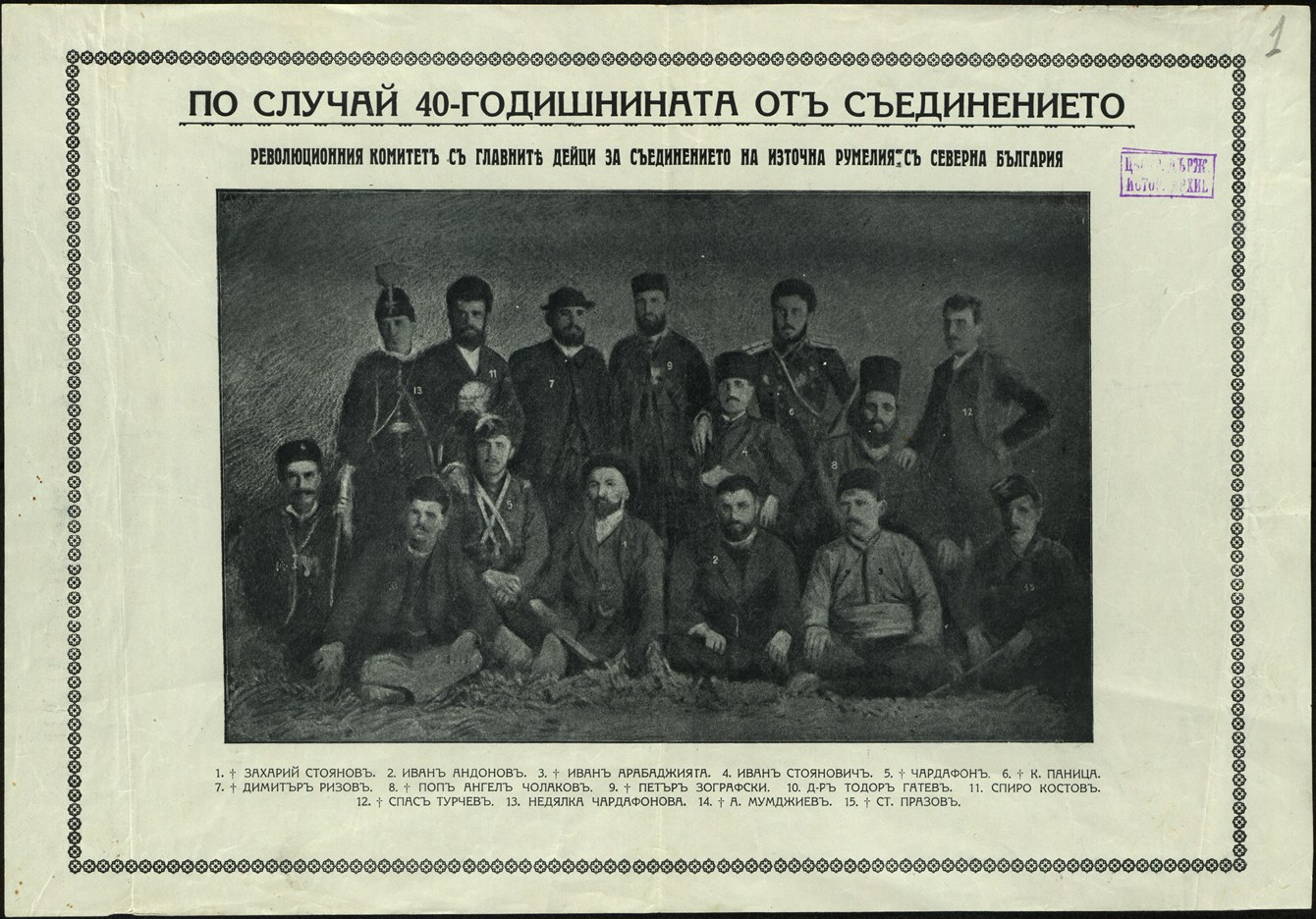

in the autumn of 1885. It was co-ordinated by the Bulgarian Secret Central Revolutionary Committee

Bulgarian Secret Central Revolutionary Committee (BSCRC) was a Bulgarian revolutionary organization founded in Plovdiv, then in Eastern Rumelia on February 10, 1885. The original purpose of the committee was to gain autonomy for the region of Ma ...

(BSCRC). Both had been parts of the Ottoman Empire, but the Principality had functioned de facto independently whilst the Rumelian province was autonomous and had an Ottoman presence. The Unification was accomplished after revolts in Eastern Rumelian towns, followed by a coup on supported by the Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

n Knyaz

, or ( Old Church Slavonic: Кнѧзь) is a historical Slavic title, used both as a royal and noble title in different times of history and different ancient Slavic lands. It is usually translated into English as prince or duke, dependi ...

Alexander I Alexander I may refer to:

* Alexander I of Macedon, king of Macedon 495–454 BC

* Alexander I of Epirus (370–331 BC), king of Epirus

* Pope Alexander I (died 115), early bishop of Rome

* Pope Alexander I of Alexandria (died 320s), patriarch of A ...

. The BSCRC, formed by Zahari Stoyanov

Zahariy Stoyanov ( bg, Захарий Стоянов; archaic: ) (1850 – 2 September 1889), born Dzhendo Stoyanov Dzhedev ( bg, Джендо Стоянов Джедев), was a Bulgarian revolutionary, writer, and historian.

A participant ...

, began actively popularizing the idea of unification by means of the press and public demonstrations in the spring of 1885.

Background

The 10thRusso-Turkish War (1877–1878)

The Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 ( tr, 93 Harbi, lit=War of ’93, named for the year 1293 in the Islamic calendar; russian: Русско-турецкая война, Russko-turetskaya voyna, "Russian–Turkish war") was a conflict between th ...

ended with the signing of the preliminary Treaty of San Stefano

The 1878 Treaty of San Stefano (russian: Сан-Стефанский мир; Peace of San-Stefano, ; Peace treaty of San-Stefano, or ) was a treaty between the Russian and Ottoman empires at the conclusion of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-18 ...

, which cut large territories off the Ottoman Empire. Bulgaria was resurrected after 482 years of foreign rule, albeit as a Principality under Ottoman suzerainty.

The Russian diplomats knew that Bulgaria would not remain within these borders for very long — the San Stefano peace was called "preliminary" by the Russians themselves. The Berlin Congress

The Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878) was a diplomatic conference to reorganise the states in the Balkan Peninsula after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, which had been won by Russia against the Ottoman Empire. Represented at th ...

began on and ended on with the Berlin Treaty that created a vassal Bulgarian state in the lands between the Balkans and the Danube. The area between the Balkan Mountains and the Rila

Rila ( bg, Рила, ) is the highest mountain range of Bulgaria, the Balkan Peninsula and Southeast Europe. It is situated in southwestern Bulgaria and forms part of the Rila– Rhodope Massif. The highest summit is Musala at an elevation of 2, ...

and Rhodope Mountains

The Rhodopes (; bg, Родопи, ; el, Ροδόπη, ''Rodopi''; tr, Rodoplar) are a mountain range in Southeastern Europe, and the largest by area in Bulgaria, with over 83% of its area in the southern part of the country and the remainder in ...

became an autonomous Ottoman province called Eastern Rumelia

Eastern Rumelia ( bg, Източна Румелия, Iztochna Rumeliya; ota, , Rumeli-i Şarkî; el, Ανατολική Ρωμυλία, Anatoliki Romylia) was an autonomous province (''oblast'' in Bulgarian, '' vilayet'' in Turkish) in the Ott ...

. The separation of southern Bulgaria into a different administrative region was a guarantee against the fears expressed by Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

and Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

that Bulgaria would gain access to the Aegean Sea, which logically meant that Russia was getting closer to the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

.

The third large portion of San Stefano Bulgaria — Macedonia — did not get even this slight taste of liberty, as it remained in the Ottoman borders like it had been before the war.

Organization

In these conditions it was natural that Bulgarians in Bulgaria, Eastern Rumelia and Macedonia all strived for unity. The first attempt was made in 1880. The new British prime minister,

In these conditions it was natural that Bulgarians in Bulgaria, Eastern Rumelia and Macedonia all strived for unity. The first attempt was made in 1880. The new British prime minister, William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-con ...

(who had strongly supported the Bulgarian cause in the past) made Bulgarian politicians hope that the British policy on the Eastern Question was about to change, and that it will support and look favourably upon an eventual Union. Unfortunately, the change of government did not bring a change in Great Britain's interests. Secondly, there was a possible conflict growing between the Ottoman Empire on one side and Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

and Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = ...

on the other.

The Union activists from Eastern Rumelia sent Stefan Panaretov, a lecturer in Robert College

The American Robert College of Istanbul ( tr, İstanbul Özel Amerikan Robert Lisesi or ), often shortened to Robert, or RC, is a highly selective, independent, co-educational high school in Turkey.The Turkish education system divides schools ...

, to consult the British opinion on the planned Unification. Gladstone's government though, did not accept these plans. Disagreement came from Imperial Russia

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. The ...

as well, which was strictly following the decisions taken during the Berlin Congress. Meanwhile, the tensions between Greece and the Ottoman Empire had settled, which finally brought the first Unification attempt to a failure.

By mid-1885 most of the active unionists in Eastern Rumelia shared the vision that the preparation of a revolution in Macedonia should be postponed and all efforts should be concentrated on the unification of Bulgaria and Eastern Rumelia. The Bulgarian Knyaz Alexander I was also drawn to this cause. His relations with Russia had worsened to such extent that the Russian Emperor and the pro-Russian circles in Bulgaria openly called for Alexander's abdication . The young knyaz saw that his support for the Unification is his only chance for political survival.

The act of Unification

The Unification was initially scheduled for the middle of September, while the Rumelian militia was mobilized for performing manoeuvres. The plan called for the Unification to be announced on , but on a riot began in Panagyurishte (then in Eastern Rumelia) that was brought under control the same day by the police. The demonstration demanded Unification with Bulgaria. A little later this example was followed in the village of Goliamo Konare. An armed squad was formed there, under the leadership of Prodan Tishkov (mostly known as Chardafon) — the local leader of the BSCRC. BSCRC representatives were sent to different towns in the province, where they had to gather groups of rebels and send them toPlovdiv

Plovdiv ( bg, Пловдив, ), is the second-largest city in Bulgaria, standing on the banks of the Maritsa river in the historical region of Thrace. It has a population of 346,893 and 675,000 in the greater metropolitan area. Plovdiv is the ...

, the capital of Eastern Rumelia, where they were under the command of Major Danail Nikolaev.

Meanwhile, military manoeuvres were being carried out in the outskirts of Plovdiv. Major Danail Nikolaev, who was in charge of the manoeuvres, was aware of and supported the unionists. On , Rumelian militia (Eastern Rumelia's armed forces) and armed unionist groups entered Plovdiv and took over the Governor's residence.

The Governor Gavril Krastevich, was arrested by the rebels and paraded through the streets of Plovdiv before being expelled to Constantinople.

A temporary government was formed immediately, with Georgi Stranski at its head. Major Danail Nikolaev was appointed commander of armed forces. With help from Russian officers, he created the strategical plan for defence against the expected Ottoman intervention. Mobilization was declared in Eastern Rumelia.

As soon as it took power on , the temporary government sent a telegram, asking the knyaz to accept the Unification. On Alexander I answered with a special manifest. On the next day, accompanied by the prime minister Petko Karavelov and the head of Parliament

Meanwhile, military manoeuvres were being carried out in the outskirts of Plovdiv. Major Danail Nikolaev, who was in charge of the manoeuvres, was aware of and supported the unionists. On , Rumelian militia (Eastern Rumelia's armed forces) and armed unionist groups entered Plovdiv and took over the Governor's residence.

The Governor Gavril Krastevich, was arrested by the rebels and paraded through the streets of Plovdiv before being expelled to Constantinople.

A temporary government was formed immediately, with Georgi Stranski at its head. Major Danail Nikolaev was appointed commander of armed forces. With help from Russian officers, he created the strategical plan for defence against the expected Ottoman intervention. Mobilization was declared in Eastern Rumelia.

As soon as it took power on , the temporary government sent a telegram, asking the knyaz to accept the Unification. On Alexander I answered with a special manifest. On the next day, accompanied by the prime minister Petko Karavelov and the head of Parliament Stefan Stambolov

Stefan Nikolov Stambolov ( bg, Стефан Николов Стамболов) (31 January 1854 OS– 19 July 1895 OS) was a Bulgarian politician, journalist, revolutionary, and poet who served as Prime Minister and regent. He is consider ...

, Knyaz Alexander I entered the capital of the former Eastern Rumelia. This gesture confirmed the unionists' actions as a fait accompli. But the difficulties of the diplomatic and military defence of the Union lay ahead.

International response to the Unification

In the years after the signing of the Berlin Treaty, the St. Petersburg government had often expressed its view that the creation of Eastern Rumelia out of Southern Bulgaria was an unnatural division and would be short-lived. Russia knew that the Unification would undoubtedly come soon and took important measures for its preparation. First, Russia exerted successful diplomatic pressure upon the Ottoman Empire constraining it from sending forces into Eastern Rumelia. Also, in 1881, in a special protocol, created after the re-establishment of theLeague of the Three Emperors

The League of the Three Emperors or Union of the Three Emperors (german: Dreikaiserbund) was an alliance between the German, Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires, from 1873 to 1887. Chancellor Otto von Bismarck took full charge of German foreign p ...

, it was noted that Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

and Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

would show support for a possible union act of the Bulgarians.

Russia

Following the establishment of the Principality of Bulgaria, the head of Russian temporary administrationAlexander Dondukov-Korsakov

Dondukov is a Russian princely family descending from Donduk-Ombo, the sixth Khan (title), khan of the Kalmucks (reigned 1737–41). In 1732 he led 11,000 Kalmuck households from the Volga banks to the border of the Ottoman Empire at the Kuban Rive ...

sought to create the foundations for Russian influence over the new state. Upon the ascension of Knyaz Alexander I to the Bulgarian throne, Russia dispatched numerous military officers and consultants to Bulgaria to further its diplomatic goals in the region. In 1883, Knyaz Alexander I began removing Russian advisors from their positions in an effort to assert his independence. When Bulgarian revolutionaries removed the pro-Russian governor of Eastern Rumelia Gavril Krastevich, Russian Czar Alexander III of Russia

Alexander III ( rus, Алекса́ндр III Алекса́ндрович, r=Aleksandr III Aleksandrovich; 10 March 18451 November 1894) was Emperor of Russia, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Finland from 13 March 1881 until his death in 18 ...

became enraged. Ordering all Russian advisors to abandon Bulgaria and stripped Knyaz Alexander I of his rank in the Russian military. Thus while Russia supported Bulgaria during the Berlin Congress, it was firmly opposed to Bulgarian unification.

United Kingdom

In autumn 1885, Knyaz Alexander I met with British Prime Minister Lord Salisbury during an official visit to London. Convincing him that the establishment of aGreater Bulgaria

Bulgarian irredentism is a term to identify the territory associated with a historical national state and a modern Bulgarian irredentist nationalist movement in the 19th and 20th centuries, which would include most of Macedonia, Thrace an ...

was within the interests of the British state. While Salisbury had fiercely argued for the separation Eastern Rumelia during the Berlin Congress, he then claimed that the circumstances had changed; and the unification was necessary, as it would prevent Russian expansion towards Constantinople. The government circles in London initially thought that powerful support by St. Petersburg stood behind the bold Bulgarian act. They soon realised the reality of the situation, and after the Russian official position was announced, Great Britain gave its support for the Bulgarian cause, but not until Bulgarian-Ottoman negotiations began.

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

's position was determined by its policy towards Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia ( Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hu ...

. In a secret treaty

A secret treaty is a treaty ( international agreement) in which the contracting state parties have agreed to conceal the treaty's existence or substance from other states and the public.Helmut Tichy and Philip Bittner, "Article 80" in Olivier D ...

from 1881, Austria-Hungary accepted Serbia's "right" to expand in the direction of Macedonia. Austria-Hungary's aim was to win influence in Serbia, while at the same time directing Serbian territorial appetites towards the south instead of north and north-west. Also, Austria-Hungary had always opposed the creation of a large Slavonic state in the Balkans of the sort that a unified Bulgaria would become.

France and Germany

They supported the Russian proposal of an international conference in the Ottoman capital.Ottoman Empire

After the Unification was already a fact, it took three days for Constantinople to become aware of what had actually happened. A new problem then arose: according to the Berlin treaty the Sultan was only allowed to send troops to Eastern Rumelia at the request of Eastern Rumelia's governor. Gavril Krastevich, the governor at the time, made no such request. At the same time the Ottoman Empire was advised in harsh tone both by London and St. Petersburg not to take any such actions and instead to wait for the decision of the international conference. The Ottomans did not attack Bulgaria, neither intervened in the

After the Unification was already a fact, it took three days for Constantinople to become aware of what had actually happened. A new problem then arose: according to the Berlin treaty the Sultan was only allowed to send troops to Eastern Rumelia at the request of Eastern Rumelia's governor. Gavril Krastevich, the governor at the time, made no such request. At the same time the Ottoman Empire was advised in harsh tone both by London and St. Petersburg not to take any such actions and instead to wait for the decision of the international conference. The Ottomans did not attack Bulgaria, neither intervened in the Serbo-Bulgarian War

The Serbo-Bulgarian War or the Serbian–Bulgarian War ( bg, Сръбско-българска война, ''Srăbsko-bălgarska voyna'', sr, Српско-бугарски рат, ''Srpsko-bugarski rat'') was a war between the Kingdom of Ser ...

. On the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria signed the Tophane Agreement

The Tophane Agreement was a treaty between the Principality of Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire signed on during an ambassadorial conference in Istanbul. The agreement was named after the Istanbul neighborhood Tophane, located in Beyoğlu distri ...

, which recognized the Prince of Bulgaria as Governor-General of the autonomous Ottoman Province Eastern Rumelia. In this way, the de facto Unification of Bulgaria which had taken place on 18 September .S. 6 September1885, was de jure recognized.

Greece

According to P. Karolidis' calculations Rumelia was inhabited by over 250,000 ethnic Greeks and Greek was among Eastern Rumelia's official languages. Following the proclamation of unification, Greek prime minister Theodoros Diligiannis protested against the violation of the Treaty of Berlin along with Serbia. Protests broke out in Athens,Volos

Volos ( el, Βόλος ) is a coastal port city in Thessaly situated midway on the Greek mainland, about north of Athens and south of Thessaloniki. It is the sixth most populous city of Greece, and the capital of the Magnesia regional unit ...

, Kalamata

Kalamáta ( el, Καλαμάτα ) is the second most populous city of the Peloponnese peninsula, after Patras, in southern Greece and the largest city of the homonymous administrative region. As the capital and chief port of the Messenia regi ...

and other parts of Greece. The protesters demanded the annexation of Ottoman Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinri ...

in order to counterbalance the strengthening of the Bulgarian state. Diligiannis responded by declaring mobilization

Mobilization is the act of assembling and readying military troops and supplies for war. The word ''mobilization'' was first used in a military context in the 1850s to describe the preparation of the Prussian Army. Mobilization theories an ...

on 25 September 1885. Diligiannis informed the Great Powers that he did not intend to get involved in a war with the Ottomans and only sought to appease the pro-war part of the population. Three of his ministers namely Antonopoulos, Zygomalas and Romas urged him to invade Epirus and organize a revolt in Ottoman Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

in order to restore the status quo ante bellum

The term ''status quo ante bellum'' is a Latin phrase meaning "the situation as it existed before the war".

The term was originally used in treaties to refer to the withdrawal of enemy troops and the restoration of prewar leadership. When use ...

. Ethnic Greeks residing in Constantinople likewise petition the sultan to declare war on Bulgaria. The loss of Eastern Rumelia was seen as a threat to the Greek ambition of expanding into Macedonia and uniting all Greek populated lands. Having amassed 80,000 soldiers at the Ottoman border Diligiannis found himself in a zugzwang

Zugzwang (German for "compulsion to move", ) is a situation found in chess and other turn-based games wherein one player is put at a disadvantage because of their obligation to make a move; a player is said to be "in zugzwang" when any legal mov ...

. A defeat in a war with the Ottomans could prove disastrous, while the dispersal of the Greek army would mean the loss of popular support, all while the costs of maintaining the army afoot mounted.

On 14 April 1886, the Great Powers (with the exception of France) ordered Greece to demobilize its forces within a week. On 8 May, the Great Powers enacted a naval blockade

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It include ...

against Greece (France abstained) in order to force it into demobilizing. Dilligiannis resigned from his position citing the blockade, bringing Charilaos Trikoupis

Charilaos Trikoupis ( el, Χαρίλαος Τρικούπης; 11 July 1832 – 30 March 1896) was a Greek politician who served as a Prime Minister of Greece seven times from 1875 until 1895.

He is best remembered for introducing the vote of c ...

back to power. A group of nationalist Greek officers launched incursions across the Ottoman border leading to five days of clashes without Trikoupis's knowledge or approval. Trikoupis demobilized the army and the naval blockade of Greece was lifted on 7 June. Greece had spent 133 million drachmas

The drachma ( el, δραχμή , ; pl. ''drachmae'' or ''drachmas'') was the currency used in Greece during several periods in its history:

# An ancient Greek currency unit issued by many Greek city states during a period of ten centuries, fr ...

without achieving any of its foreign policy goals, while its society became deeply polarized between the supporters of Diligiannis and Trikoupis respectively.

Serbia

Serbia's position was similar to that of Greece. The Serbians asked for considerable territorial compensations along the whole western border with Bulgaria. Rebuffed by Bulgaria, but assured of support from Austria-Hungary, kingMilan I

Milan Obrenović ( sr-cyr, Милан Обреновић, Milan Obrenović; 22 August 1854 – 11 February 1901) reigned as the prince of Serbia from 1868 to 1882 and subsequently as king from 1882 to 1889. Milan I unexpectedly abdicated in ...

declared war on Bulgaria on . However, after the decisive Battle of Slivnitsa

The Battle of Slivnitsa ( bg, Битка при Сливница, sr, Битка на Сливници) was a victory of the Bulgarian army over the Serbians on 17–19 November 1885 in the Serbo-Bulgarian War. It solidified the unification ...

, the Serbs suffered a quick defeat and the Bulgarians advanced into Serbian territory up to Pirot

Pirot ( sr-cyr, Пирот) is a city and the administrative center of the Pirot District in southeastern Serbia. According to 2011 census, the urban area of the city has a population of 38,785, while the population of the city administrative are ...

. Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

demanded the ceasing of military actions, threatening that otherwise the Bulgarian forces would meet Austro-Hungarian troops. The ceasefire was signed on 28 November 1885. On 3 March 1886, the peace treaty was signed in Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north o ...

. According to its terms, no changes were made along the Bulgarian-Serbian border, preserving the Unification of Bulgaria.

Commemoration

*The Unification Day is celebrated on 6 September as a national holiday in Bulgaria. *The town of Saedinenie in Plovdiv Province, Bulgaria, bears the name of the Unification of Bulgaria. * Saedinenie Snowfield onLivingston Island

Livingston Island (Russian name ''Smolensk'', ) is an Antarctic island in the Southern Ocean, part of the South Shetlands Archipelago, a group of Antarctic islands north of the Antarctic Peninsula. It was the first land discovered south of 60 ...

in the South Shetland Islands

The South Shetland Islands are a group of Antarctic islands with a total area of . They lie about north of the Antarctic Peninsula, and between southwest of the nearest point of the South Orkney Islands. By the Antarctic Treaty of 1 ...

, Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest cont ...

is named for the Unification of Bulgaria.

Notes

References

* * *Further reading

*. * * * * * * * * Jono Mitev — ''"The Unification"'' / Йоно Митев — ''"Съединението"'', Военно издателство {{Authority control National unifications 1885 in Bulgaria 1885 in politics Bulgaria–Ottoman Empire relations