Uncle Tom's Cabin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an

Stowe, a

Stowe, a

''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' first appeared as a 40-week serial in ''

''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' first appeared as a 40-week serial in ''

The book opens with a

The book opens with a

During Eliza's escape, she meets up with her husband George Harris, who had run away previously. They decide to attempt to reach Canada, but are tracked by Tom Loker, a slave hunter hired by Mr. Haley. Eventually Loker and his men trap Eliza and her family, causing George to shoot him in the side. Worried that Loker may die, Eliza convinces George to bring the slave hunter to a nearby

During Eliza's escape, she meets up with her husband George Harris, who had run away previously. They decide to attempt to reach Canada, but are tracked by Tom Loker, a slave hunter hired by Mr. Haley. Eventually Loker and his men trap Eliza and her family, causing George to shoot him in the side. Worried that Loker may die, Eliza convinces George to bring the slave hunter to a nearby

Legree begins to hate Tom when Tom refuses Legree's order to whip his fellow slave. Legree beats Tom viciously and resolves to crush his new slave's faith in

Legree begins to hate Tom when Tom refuses Legree's order to whip his fellow slave. Legree beats Tom viciously and resolves to crush his new slave's faith in

*

*

One of the subthemes presented in the novel is

One of the subthemes presented in the novel is

''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' is written in the sentimental and melodramatic style common to 19th-century

''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' is written in the sentimental and melodramatic style common to 19th-century

''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' had an "incalculable" impact on the 19th-century world and captured the imagination of many Americans. In a likely apocryphal story that alludes to the novel's impact, when

''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' had an "incalculable" impact on the 19th-century world and captured the imagination of many Americans. In a likely apocryphal story that alludes to the novel's impact, when  ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' also created great interest in the United Kingdom. The first London edition appeared in May 1852 and sold 200,000 copies. Some of this interest was because of British antipathy to America. As one prominent writer explained, "The evil passions which ''Uncle Tom'' gratified in England were not hatred or vengeance f slavery but national jealousy and national vanity. We have long been smarting under the conceit of America—we are tired of hearing her boast that she is the freest and the most enlightened country that the world has ever seen. Our clergy hate her voluntary system—our

''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' also created great interest in the United Kingdom. The first London edition appeared in May 1852 and sold 200,000 copies. Some of this interest was because of British antipathy to America. As one prominent writer explained, "The evil passions which ''Uncle Tom'' gratified in England were not hatred or vengeance f slavery but national jealousy and national vanity. We have long been smarting under the conceit of America—we are tired of hearing her boast that she is the freest and the most enlightened country that the world has ever seen. Our clergy hate her voluntary system—our

Many modern scholars and readers have criticized the book for condescending racist descriptions of the black characters' appearances, speech, and behavior, as well as the passive nature of Uncle Tom in accepting his fate. The novel's creation and use of common

Many modern scholars and readers have criticized the book for condescending racist descriptions of the black characters' appearances, speech, and behavior, as well as the passive nature of Uncle Tom in accepting his fate. The novel's creation and use of common

In response to ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'', writers in the Southern United States produced a number of books to rebut Stowe's novel. This so-called Anti-Tom literature generally took a pro-slavery viewpoint, arguing that the issues of slavery as depicted in Stowe's book were overblown and incorrect. The novels in this genre tended to feature a benign white patriarchal master and a pure wife, both of whom presided over childlike slaves in a benevolent extended family style plantation. The novels either implied or directly stated that African Americans were a childlike people unable to live their lives without being directly overseen by white people.

Among the most famous anti-Tom books are ''

In response to ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'', writers in the Southern United States produced a number of books to rebut Stowe's novel. This so-called Anti-Tom literature generally took a pro-slavery viewpoint, arguing that the issues of slavery as depicted in Stowe's book were overblown and incorrect. The novels in this genre tended to feature a benign white patriarchal master and a pure wife, both of whom presided over childlike slaves in a benevolent extended family style plantation. The novels either implied or directly stated that African Americans were a childlike people unable to live their lives without being directly overseen by white people.

Among the most famous anti-Tom books are ''

''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' has been adapted several times as a film. Most of these movies were created during the

''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' has been adapted several times as a film. Most of these movies were created during the

James Baird Weaver

from archive. org, 2007. Retrieved February 17, 2007. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

University of Virginia Web site "''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' and American Culture: A Multi-Media Archive"

– edited by Stephen Railton, covers 1830 to 1930, offering links to primary and bibliographic sources on the cultural background, various editions, and public reception of Harriet Beecher Stowe's influential novel. The site also provides the full text of the book, audio and video clips, and examples of related merchandising. *

''Uncle Tom's Cabin''

available at

anti-slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

novel by American author

American literature is literature written or produced in the United States of America and in the colonies that preceded it. The American literary tradition thus is part of the broader tradition of English-language literature, but also inc ...

Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two volumes

Volume is a measure of occupied three-dimensional space. It is often quantified numerically using SI derived units (such as the cubic metre and litre) or by various imperial or US customary units (such as the gallon, quart, cubic inch). The defi ...

in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans and slavery in the U.S., and is said to have "helped lay the groundwork for the merican

''Merican'' is an EP by the American punk rock band the Descendents, released February 10, 2004. It was the band's first release for Fat Wreck Chords and served as a pre-release to their sixth studio album ''Cool to Be You'', released the follow ...

Civil War".

Stowe, a Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

-born woman of English descent, was part of the religious Beecher family

Originating in New England, one particular Beecher family in the 19th century was a political family notable for issues of religion, civil rights, and social reform. Notable members of the family include clergy ( Congregationalists), educators, au ...

and an active abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

. She wrote the sentimental novel

The sentimental novel or the novel of sensibility is an 18th-century literary genre which celebrates the emotional and intellectual concepts of sentiment, sentimentalism, and sensibility. Sentimentalism, which is to be distinguished from sens ...

to depict the reality of slavery while also asserting that Christian love could overcome slavery. The novel focuses on the character of Uncle Tom, a long-suffering black slave around whom the stories of the other characters revolve.

In the United States, ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' was the best-selling novel and the second best-selling book of the 19th century, following the Bible. It is credited with helping fuel the abolitionist cause in the 1850s. The influence attributed to the book was so great that a likely apocryphal story arose of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

meeting Stowe at the start of the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

and declaring, "So this is the little lady who started this great war."

The book and the plays

Play most commonly refers to:

* Play (activity), an activity done for enjoyment

* Play (theatre), a work of drama

Play may refer also to:

Computers and technology

* Google Play, a digital content service

* Play Framework, a Java framework

* P ...

it inspired helped popularize a number of negative stereotypes about black people including that of the namesake character "Uncle Tom

Uncle Tom is the title character of Harriet Beecher Stowe's 1852 novel, '' Uncle Tom's Cabin''. The character was seen by many readers as a ground-breaking humanistic portrayal of a slave, one who uses nonresistance and gives his life to prot ...

". The term came to be associated with an excessively subservient person. These later associations with ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' have, to an extent, overshadowed the historical effects of the book as a "vital antislavery tool". However, the novel remains a "landmark" in protest literature, with later books such as ''The Jungle

''The Jungle'' is a 1906 novel by the American journalist and novelist Upton Sinclair. Sinclair's primary purpose in describing the meat industry and its working conditions was to advance socialism in the United States. However, most readers we ...

'' by Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American writer, muckraker, political activist and the 1934 Democratic Party nominee for governor of California who wrote nearly 100 books and other works in sever ...

and ''Silent Spring

''Silent Spring'' is an environmental science book by Rachel Carson. Published on September 27, 1962, the book documented the environmental harm caused by the indiscriminate use of pesticides. Carson accused the chemical industry of spreading d ...

'' by Rachel Carson

Rachel Louise Carson (May 27, 1907 – April 14, 1964) was an American marine biologist, writer, and conservationist whose influential book '' Silent Spring'' (1962) and other writings are credited with advancing the global environmental ...

owing a large debt to it.

Sources

Stowe, a

Stowe, a Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

-born teacher at the Hartford Female Seminary

Hartford Female Seminary in Hartford, Connecticut was established in 1823, by Catharine Beecher, making it one of the first major educational institutions for women in the United States. By 1826 it had enrolled nearly 100 students. It implemente ...

and an active abolitionist, wrote the novel as a response to the passage, in 1850, of the second Fugitive Slave Act

A fugitive (or runaway) is a person who is fleeing from custody, whether it be from jail, a government arrest, government or non-government questioning, vigilante violence, or outraged private individuals. A fugitive from justice, also kno ...

. Much of the book was composed at her house in Brunswick, Maine

Brunswick is a town in Cumberland County, Maine, United States. The population was 21,756 at the 2020 United States Census. Part of the Portland-South Portland-Biddeford metropolitan area, Brunswick is home to Bowdoin College, the Bowdoin Intern ...

, where her husband, Calvin Ellis Stowe

Calvin Ellis Stowe (April 6, 1802 – August 22, 1886) was an American Biblical scholar who helped spread public education in the United States. Over his career, he was a professor of languages and Biblical and sacred literature at Andover Theolo ...

, taught at his '' alma mater'', Bowdoin College.

Stowe was partly inspired to create ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' by the slave narrative

The slave narrative is a type of literary genre involving the (written) autobiographical accounts of enslaved Africans, particularly in the Americas. Over six thousand such narratives are estimated to exist; about 150 narratives were published as s ...

''The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, as Narrated by Himself

''The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, as Narrated by Himself'' is a slave narrative written by Josiah Henson, who would later become famous for being the basis of the title character from Harriet Beecher St ...

'' (1849). Henson Henson may refer to:

__NOTOC__ Places United States

* Henson, Colorado, a ghost town

* Henson, Missouri, an unincorporated community

* Henson Creek, Colorado

* Henson Branch, Missouri, a stream

Antarctica

* Mount Henson, Ross Dependency

Other ...

, a formerly enslaved black man, had lived and worked on a plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

in North Bethesda, Maryland

North Bethesda is an unincorporated, census-designated place in Montgomery County, Maryland, United States, located just north-west of the U.S. capital of Washington, D.C. It had a population of 50,094 as of the 2020 census. Among its neighb ...

, owned by Isaac Riley. Henson escaped slavery in 1830 by fleeing to the Province of Upper Canada (now Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central Ca ...

), where he helped other fugitive slaves settle and become self-sufficient.

Stowe was also inspired by the posthumous biography of Phebe Ann Jacobs, a devout Congregationalist of Brunswick, Maine

Brunswick is a town in Cumberland County, Maine, United States. The population was 21,756 at the 2020 United States Census. Part of the Portland-South Portland-Biddeford metropolitan area, Brunswick is home to Bowdoin College, the Bowdoin Intern ...

. Born on a slave plantation in Lake Hiawatha, New Jersey

Lake Hiawatha is an unincorporated community located within Parsippany-Troy Hills in Morris County, New Jersey, United States. The area is served as United States Postal Service as ZIP code 07034. As of the 2010 United States Census, the popu ...

, Jacobs was enslaved for most of her life, including by the president of Bowdoin College. In her final years, Jacobs lived as a free woman, laundering clothes for Bowdoin students. She achieved respect from her community due to her devout religious beliefs, and her funeral was widely attended.

Another source Stowe used as research for ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' was '' American Slavery as It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses'', a volume co-authored by Theodore Dwight Weld

Theodore Dwight Weld (November 23, 1803 – February 3, 1895) was one of the architects of the American abolitionist movement during its formative years from 1830 to 1844, playing a role as writer, editor, speaker, and organizer. He is best known ...

and the Grimké sisters

Sarah Moore Grimké (1792–1873) and Angelina Emily GrimkéUnited States. National Park Service. "Grimke Sisters." U.S. Department of the Interior, October 8, 2014. Accessed:October 14, 2014. (1805–1879), known as the Grimké sisters, were th ...

. Stowe also conducted interviews with people who escaped slavery. Stowe mentioned a number of these inspirations and sources in ''A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin

''A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin'' is a book by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. It was published to document the veracity of the depiction of slavery in Stowe's anti-slavery novel ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' (1852). First published in 1853 by Jewet ...

'' (1853). This non-fiction book was intended to not only verify Stowe's claims about slavery but also point readers to the many "publicly available documents" detailing the horrors of slavery.

Publication

''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' first appeared as a 40-week serial in ''

''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' first appeared as a 40-week serial in ''The National Era

''The National Era'' was an abolitionist newspaper published weekly in Washington, D.C., from 1847 to 1860. Gamaliel Bailey was its editor in its first year. ''The National Era Prospectus'' stated in 1847:

Each number contained four pages of ...

'', an abolitionist periodical, starting with the June 5, 1851, issue. It was originally intended as a shorter narrative that would run for only a few weeks. Stowe expanded the story significantly, however, and it was instantly popular, such that protests were sent to the ''Era'' office when she missed an issue. The final installment was released in the April 1, 1852, issue of ''Era''. Stowe arranged for the story's copyright to be registered with the United States District Court for the District of Maine

The U.S. District Court for the District of Maine (in case citations, D. Me.) is the U.S. district court for the state of Maine. The District of Maine was one of the original thirteen district courts established by the Judiciary Act of 17 ...

. She renewed her copyright in 1879 and the work entered the public domain on May 12, 1893.

While the story was still being serialized, the publisher John P. Jewett John Punchard Jewett (1814–1884) was a Boston publisher, best known for first publishing ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' in book form in 1852. Jewett was a brother of librarian Charles Coffin Jewett.

Jewett started a business in Boston publishing textbooks ...

contracted with Stowe to turn ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' into a book. Convinced the book would be popular, Jewett made the unusual decision (for the time) to have six full-page illustrations by Hammatt Billings

Charles Howland Hammatt Billings (1818–1874) was an artist and architect from Boston, Massachusetts.

Among his works are the original illustrations for ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' (both the initial printing

and an expanded 1853 edition),

the Nat ...

engraved for the first printing. Published in book form on March 20, 1852, the novel sold 3,000 copies on that day alone, and soon sold out its complete print run. In the first year after it was published, 300,000 copies of the book were sold in the United States. Eight printing presses, running incessantly, could barely keep up with the demand.

By mid-1853 sales of the book dramatically decreased and Jewett went out of business during the Panic of 1857. In June 1860 the right to publish ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' passed to the Boston firm Ticknor and Fields

Ticknor and Fields was an American publishing company based in Boston, Massachusetts. Founded as a bookstore in 1832, the business would publish many 19th century American authors including Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry James, ...

, which put the book back in print in November 1862. After that demand began to yet again increase. Derived from a presentation at the June 2007 Uncle Tom's Cabin in the Web of Culture conference, sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities, and presented by the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center (Hartford, CT) and the Uncle Tom's Cabin & American Culture Project at the University of Virginia. Houghton Mifflin Company acquired the rights from Ticknor in 1878. In 1879, a new edition of ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' was released, repackaging the novel as an "American classic". Through the 1880s until its copyright expired, the book served as a mainstay and reliable source of income for Houghton Mifflin. By the end of the nineteenth century, the novel was widely available in a large number of editions and in the United States it became the second best-selling book of that century after the Bible.

''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' sold equally well in Britain, the first London edition appearing in May 1852 and selling 200,000 copies. In a few years over 1.5 million copies of the book were in circulation in Britain, although most of these were infringing copies (a similar situation occurred in the United States). By 1857, the novel had been translated into 20 languages. Translator Lin Shu published the first Chinese translation in 1901, which was also the first American novel translated into that language.

Plot

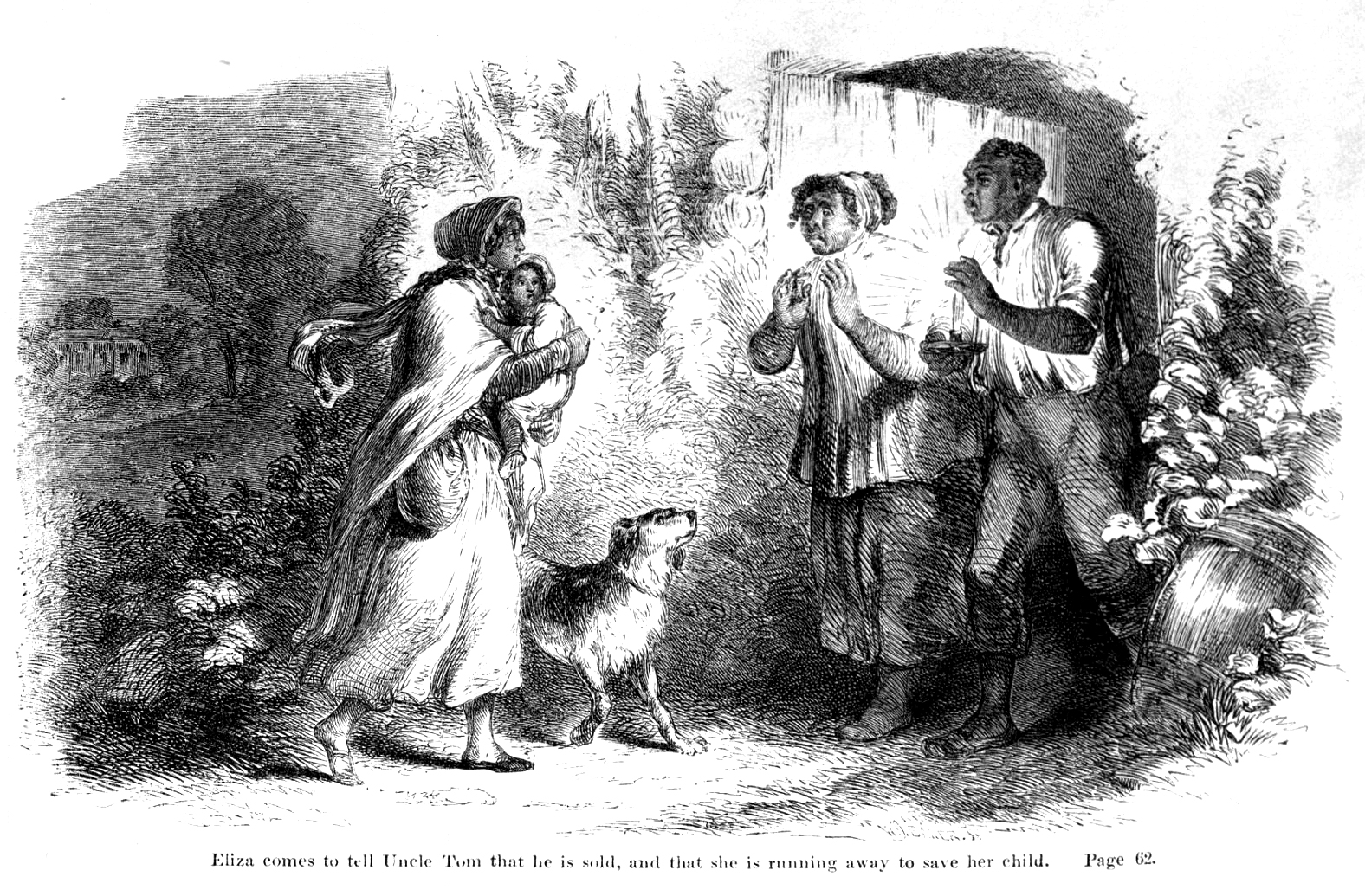

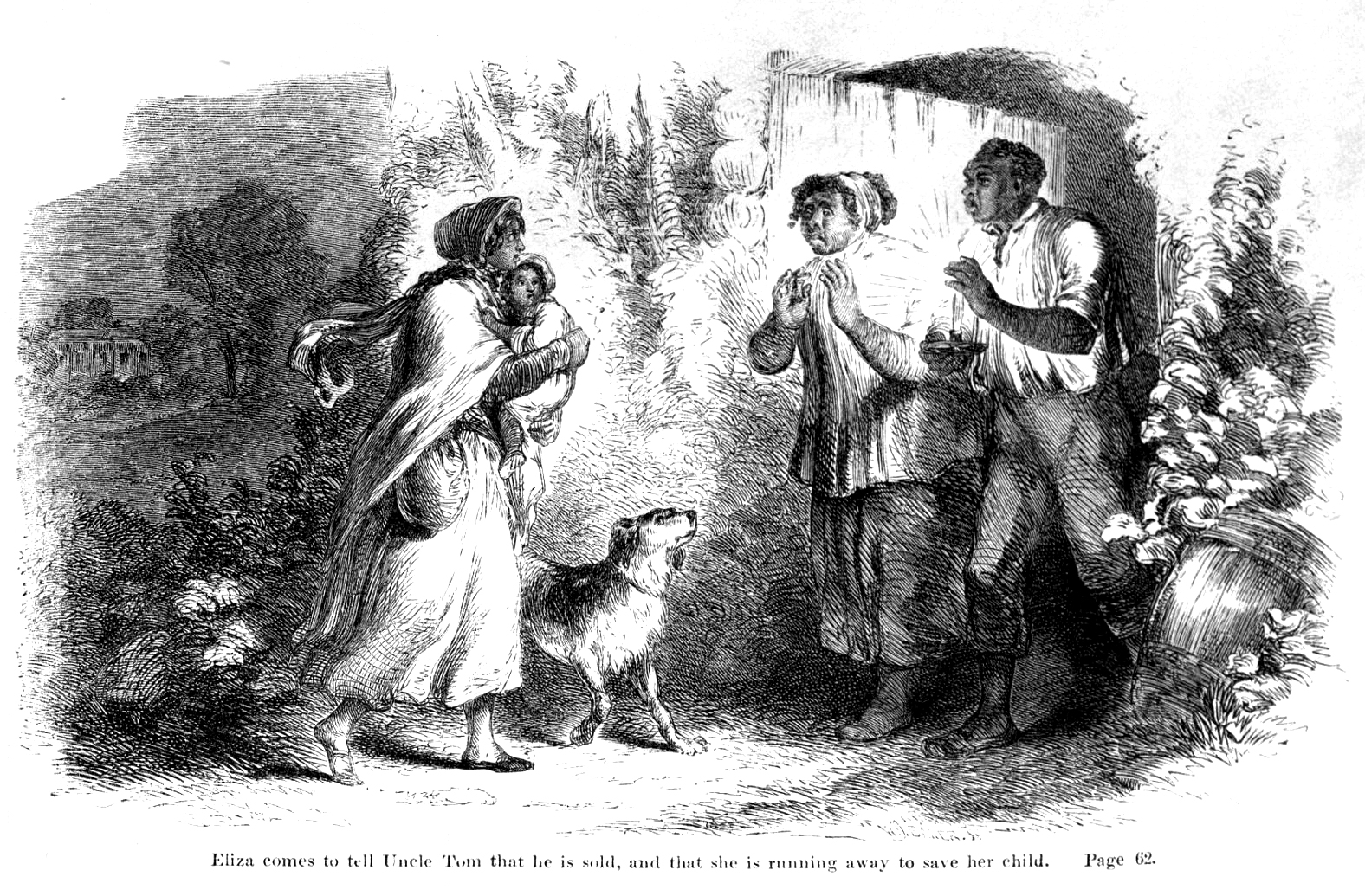

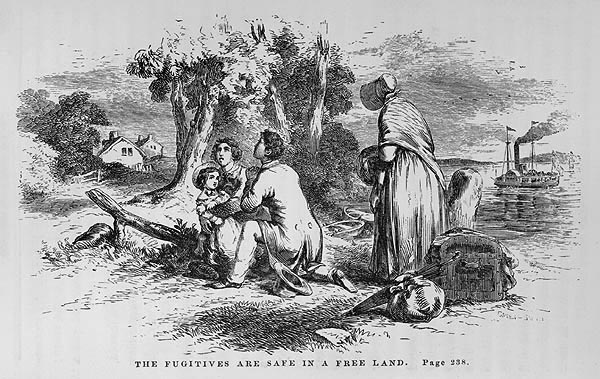

Eliza escapes with her son; Tom sold "down the river"

The book opens with a

The book opens with a Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

farmer named Arthur Shelby facing the loss of his farm because of debts. Even though he and his wife Emily Shelby believe that they have a benevolent relationship with their slaves, Shelby decides to raise the needed funds by selling two of them—Uncle Tom, a middle-aged man with a wife and children, and Harry, the son of Emily Shelby's maid Eliza—to Mr. Haley, a coarse slave trader. Emily Shelby is averse to this idea because she had promised her maid that her child would never be sold; Emily's son, George Shelby, hates to see Tom go because he sees the man as his friend and mentor.

When Eliza overhears Mr. and Mrs. Shelby discussing plans to sell Tom and Harry, Eliza determines to run away with her son. The novel states that Eliza made this decision because she fears losing her only surviving child (she had already miscarried

Miscarriage, also known in medical terms as a spontaneous abortion and pregnancy loss, is the death of an embryo or fetus before it is able to survive independently. Miscarriage before 6 weeks of gestation is defined by ESHRE as biochemical lo ...

two children). Eliza departs that night, leaving a note of apology to her mistress. She later makes a dangerous crossing over the ice of the Ohio River to escape her pursuers.

As Tom is sold, Mr. Haley takes him to a riverboat

A riverboat is a watercraft designed for inland navigation on lakes, rivers, and artificial waterways. They are generally equipped and outfitted as work boats in one of the carrying trades, for freight or people transport, including luxury un ...

on the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

and from there Tom is to be transported to a slave market. While on board, Tom meets Eva, an angelic little white girl. They quickly become friends. Eva falls into the river and Tom dives into the river to save her life. Being grateful to Tom, Eva's father Augustine St. Clare buys him from Haley and takes him with the family to their home in New Orleans. Tom and Eva begin to relate to one another because of the deep Christian faith they both share.

Eliza's family hunted; Tom's life with St. Clare

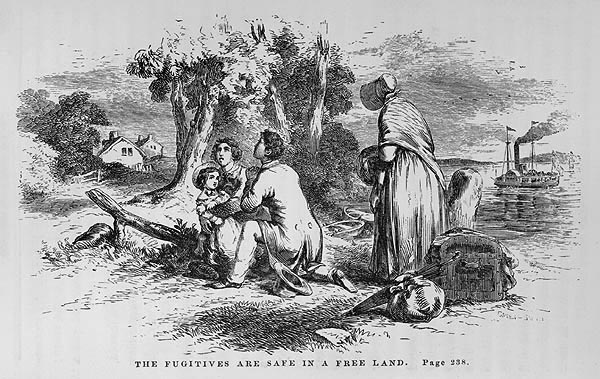

During Eliza's escape, she meets up with her husband George Harris, who had run away previously. They decide to attempt to reach Canada, but are tracked by Tom Loker, a slave hunter hired by Mr. Haley. Eventually Loker and his men trap Eliza and her family, causing George to shoot him in the side. Worried that Loker may die, Eliza convinces George to bring the slave hunter to a nearby

During Eliza's escape, she meets up with her husband George Harris, who had run away previously. They decide to attempt to reach Canada, but are tracked by Tom Loker, a slave hunter hired by Mr. Haley. Eventually Loker and his men trap Eliza and her family, causing George to shoot him in the side. Worried that Loker may die, Eliza convinces George to bring the slave hunter to a nearby Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

settlement for medical treatment.

Back in New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

, St. Clare debates slavery with his Northern cousin Ophelia who, while opposing slavery, is prejudiced against black people. St. Clare, however, believes he is not biased, even though he is a slave owner. In an attempt to show Ophelia that her views on blacks are wrong, St. Clare purchases Topsy, a young black slave, and asks Ophelia to educate her.

After Tom has lived with the St. Clares for two years, Eva grows very ill. Before she dies she experiences a vision of heaven, which she shares with the people around her. As a result of her death and vision, the other characters resolve to change their lives, Ophelia promising to throw off her personal prejudices against blacks, Topsy saying she will better herself, and St. Clare pledging to free Tom.

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Tom sold to Simon Legree

Before St. Clare can follow through on his pledge, he dies after being stabbed outside a tavern. His wife reneges on her late husband's vow and sells Tom at auction to a vicious plantation owner named Simon Legree. Tom is taken to ruralLouisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

with other new slaves including Emmeline, whom Simon Legree has purchased to use as a sex slave.

Legree begins to hate Tom when Tom refuses Legree's order to whip his fellow slave. Legree beats Tom viciously and resolves to crush his new slave's faith in

Legree begins to hate Tom when Tom refuses Legree's order to whip his fellow slave. Legree beats Tom viciously and resolves to crush his new slave's faith in God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

. Despite Legree's cruelty, Tom refuses to stop reading his Bible and comforting the other slaves as best he can. While at the plantation, Tom meets Cassy, another slave whom Legree used as a sex slave. Cassy tells her story to Tom. She was previously separated from her son and daughter when they were sold. She became pregnant again but killed the child because she could not tolerate having another child separated from her.

Tom Loker, changed after being healed by the Quakers, returns to the story. He has helped George, Eliza, and Harry enter Canada from Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( "eerie") is the fourth largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and therefore also h ...

and become free. In Louisiana, Uncle Tom almost succumbs to hopelessness as his faith in God is tested by the hardships of the plantation. He has two visions, one of Jesus and one of Eva, which renew his resolve to remain a faithful Christian, even unto death. He encourages Cassy to escape, which she does, taking Emmeline with her. When Tom refuses to tell Legree where Cassy and Emmeline have gone, Legree orders his overseers to kill Tom. As Tom is dying, he forgives the overseers who savagely beat him. Humbled by the character of the man they have killed, both men become Christians. George Shelby, Arthur Shelby's son, arrives to buy Tom's freedom, but Tom dies shortly after they meet.

Final section

On their boat ride to freedom, Cassy and Emmeline meet George Harris' sister Madame de Thoux and accompany her to Canada. Madame de Thoux and George Harris were separated in their childhood. Cassy discovers that Eliza is her long-lost daughter who was sold as a child. Now that their family is together again, they travel to France and eventuallyLiberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean ...

, the African nation created for former American slaves. George Shelby returns to the Kentucky farm, where after his father's death, he frees all his slaves. George Shelby urges them to remember Tom's sacrifice every time they look at his cabin. He decides to lead a pious Christian life just as Uncle Tom did.

Major characters

Uncle Tom

Uncle Tom is the title character of Harriet Beecher Stowe's 1852 novel, '' Uncle Tom's Cabin''. The character was seen by many readers as a ground-breaking humanistic portrayal of a slave, one who uses nonresistance and gives his life to prot ...

, the title character, was initially seen as a noble, long-suffering Christian slave. In more recent years, his name has become an epithet directed towards African-Americans who are accused of selling out

"Selling out", or "sold out" in the past tense, is a common expression for the compromising of a person's integrity, morality, authenticity, or principles by forgoing the long-term benefits of the collective or group in exchange for personal ga ...

to whites. Stowe intended Tom to be a "noble hero" and a praiseworthy person. Throughout the book, far from allowing himself to be exploited, Tom stands up for his beliefs and refuses to betray friends and family.

*Eliza is a slave and personal maid to Mrs. Shelby, who escapes to the North with her five-year-old son Harry after he is sold to Mr. Haley. Her husband, George, eventually finds Eliza and Harry in Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

and emigrates with them to Canada, then France, and finally Liberia. The character Eliza was inspired by an account given at Lane Theological Seminary

Lane Seminary, sometimes called Cincinnati Lane Seminary, and later renamed Lane Theological Seminary, was a Presbyterian theological college that operated from 1829 to 1932 in Walnut Hills, Ohio, today a neighborhood in Cincinnati. Its campus ...

in Cincinnati by John Rankin to Stowe's husband Calvin, a professor at the school. According to Rankin, in February 1838, a young slave woman, Eliza Harris, had escaped across the frozen Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

to the town of Ripley with her child in her arms and stayed at his house on her way farther north.

*Evangeline St. Clare is the daughter of Augustine St. Clare. Eva enters the narrative when Uncle Tom is traveling via steamship

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamships ...

to New Orleans to be sold, and he rescues the five- or six-year-old girl from drowning. Eva begs her father to buy Tom, and he becomes the head coachman at the St. Clare house. He spends most of his time with the angelic Eva. Eva often talks about love and forgiveness, convincing the dour slave girl Topsy that she deserves love. She even touches the heart of her Aunt Ophelia. Eventually Eva falls terminally ill

Terminal illness or end-stage disease is a disease that cannot be cured or adequately treated and is expected to result in the death of the patient. This term is more commonly used for progressive diseases such as cancer, dementia or advanced h ...

. Before dying, she gives a lock of her hair to each of the slaves, telling them that they must become Christians so that they may see each other in Heaven. On her deathbed, she convinces her father to free Tom, but because of circumstances the promise never materializes.

*Simon Legree is a cruel slave owner—a Northerner by birth—whose name has become synonymous with greed and cruelty. He is arguably the novel's main antagonist

An antagonist is a character in a story who is presented as the chief foe of the protagonist.

Etymology

The English word antagonist comes from the Greek ἀνταγωνιστής – ''antagonistēs'', "opponent, competitor, villain, enemy, riv ...

. His goal is to demoralize Tom and break him of his religious faith; he eventually orders Tom whipped to death out of frustration for his slave's unbreakable belief in God. The novel reveals that, as a young man, he had abandoned his sickly mother for a life at sea and ignored her letter to see her one last time at her deathbed. He sexually exploits Cassy, who despises him, and later sets his designs on Emmeline. It is unclear if Legree is based on any actual individuals. Reports surfaced in the late 1800s that Stowe had in mind a wealthy cotton and sugar plantation owner named Meredith Calhoun Meredith Calhoun (1805 – March 14, 1869) was a planter and slaveholder, merchant, and journalist, known for owning some of the largest plantations in the Red River area north of Alexandria, Louisiana. His workers were enslaved African Americans ...

, who settled on the Red River north of Alexandria, Louisiana

Alexandria is the ninth-largest city in the state of Louisiana and is the parish seat of Rapides Parish, Louisiana, United States. It lies on the south bank of the Red River in almost the exact geographic center of the state. It is the prin ...

. Rev. Josiah Henson

Josiah Henson (June 15, 1789 – May 5, 1883) was an author, abolitionist, and minister. Born into slavery, in Port Tobacco, Charles County, Maryland, he escaped to Upper Canada (now Ontario) in 1830, and founded a settlement and laborer's scho ...

, inspiration for the character of Uncle Tom, said that Legree was modeled after Bryce Lytton, "who broke my arm and maimed me for life."

Literary themes and theories

Major themes

''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' is dominated by a single theme: the evil and immorality of slavery. While Stowe weaves other subthemes throughout her text, such as themoral authority Moral authority is authority premised on principles, or fundamental truths, which are independent of written, or positive, laws. As such, moral authority necessitates the existence of and adherence to truth. Because truth does not change, the princi ...

of motherhood and the power of Christian love, she emphasizes the connections between these and the horrors of slavery. Stowe sometimes changed the story's voice so she could give a " homily" on the destructive nature of slavery (such as when a white woman on the steamboat carrying Tom further south states, "The most dreadful part of slavery, to my mind, is its outrages of feelings and affections—the separating of families, for example."). One way Stowe showed the evil of slavery was how this "peculiar institution" forcibly separated families from each other.

One of the subthemes presented in the novel is

One of the subthemes presented in the novel is temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

*Temperance (group), Canadian danc ...

. Stowe made it somewhat subtle and in some cases she wove it into events that would also support the dominant theme. One example of this is when Augustine St. Clare is killed, he attempted to stop a brawl between two inebriated men in a cafe and was stabbed. Another example is the death of Prue, who was whipped to death for being drunk on a consistent basis; however, her reasons for doing so is due to the loss of her baby. In the opening of the novel, the fates of Eliza and her son are being discussed between slave owners over wine. Considering that Stowe intended this to be a subtheme, this scene could foreshadow future events that put alcohol in a bad light.

Because Stowe saw motherhood as the "ethical and structural model for all of American life" and also believed that only women had the moral authority Moral authority is authority premised on principles, or fundamental truths, which are independent of written, or positive, laws. As such, moral authority necessitates the existence of and adherence to truth. Because truth does not change, the princi ...

to save the United States from the demon of slavery, another major theme of ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' is the moral power and sanctity of women. Through characters like Eliza, who escapes from slavery to save her young son (and eventually reunites her entire family), or Eva, who is seen as the "ideal Christian", Stowe shows how she believed women could save those around them from even the worst injustices. Though later critics have noted that Stowe's female characters are often domestic

Domestic may refer to:

In the home

* Anything relating to the human home or family

** A domestic animal, one that has undergone domestication

** A domestic appliance, or home appliance

** A domestic partnership

** Domestic science, sometimes c ...

clichés instead of realistic women, Stowe's novel "reaffirmed the importance of women's influence" and helped pave the way for the women's rights movement

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, ...

in the following decades.

Stowe's puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

ical religious beliefs show up in the novel's final, overarching theme—the exploration of the nature of Christian love and how she feels Christian theology is fundamentally incompatible with slavery. This theme is most evident when Tom urges St. Clare to "look away to Jesus" after the death of St. Clare's beloved daughter Eva. After Tom dies, George Shelby eulogizes Tom by saying, "What a thing it is to be a Christian." Because Christian themes play such a large role in ''Uncle Tom's Cabin''—and because of Stowe's frequent use of direct authorial interjections on religion and faith—the novel often takes the "form of a sermon".

Literary theories

Over the years scholars have postulated a number of theories about what Stowe was trying to say with the novel (aside from the major theme of condemning slavery). For example, as an ardent Christian and active abolitionist, Stowe placed many of her religious beliefs into the novel. Some scholars have stated that Stowe saw her novel as offering a solution to the moral and political dilemma that troubled many slavery opponents: whether engaging in prohibited behavior was justified in opposing evil. Was the use of violence to oppose the violence of slavery and the breaking of proslavery laws morally defensible? Which of Stowe's characters should be emulated, the passive Uncle Tom or the defiant George Harris? Stowe's solution was similar toRalph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a champ ...

's: God's will would be followed if each person sincerely examined his principles and acted on them.

Scholars have also seen the novel as expressing the values and ideas of the Free Will Movement. In this view, the character of George Harris embodies the principles of free labor, and the complex character of Ophelia represents those Northerners who condoned compromise with slavery. In contrast to Ophelia is Dinah, who operates on passion. During the course of the novel Ophelia is transformed, just as the Republican Party (three years later) proclaimed that the North must transform itself and stand up for its antislavery principles.

Feminist theory

Feminist theory is the extension of feminism into theoretical, fictional, or philosophical discourse. It aims to understand the nature of gender inequality. It examines women's and men's social roles, experiences, interests, chores, and femin ...

can also be seen at play in Stowe's book, with the novel as a critique of the patriarchal nature of slavery. For Stowe, blood relations rather than paternalistic relations between masters and slaves formed the basis of families. Moreover, Stowe viewed national solidarity as an extension of a person's family, thus feelings of nationality stemmed from possessing a shared race. Consequently, she advocated African colonization for freed slaves and not amalgamation into American society.

The book has also been seen as an attempt to redefine masculinity as a necessary step toward the abolition of slavery. In this view, abolitionists had begun to resist the vision of aggressive and dominant men that the conquest and colonization of the early 19th century had fostered. To change the notion of manhood so that men could oppose slavery without jeopardizing their self-image or their standing in society, some abolitionists drew on principles of women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

and Christianity as well as passivism, and praised men for cooperation, compassion, and civic spirit. Others within the abolitionist movement argued for conventional, aggressive masculine action. All the men in Stowe's novel are representations of either one kind of man or the other.

Style

''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' is written in the sentimental and melodramatic style common to 19th-century

''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' is written in the sentimental and melodramatic style common to 19th-century sentimental novel

The sentimental novel or the novel of sensibility is an 18th-century literary genre which celebrates the emotional and intellectual concepts of sentiment, sentimentalism, and sensibility. Sentimentalism, which is to be distinguished from sens ...

s and domestic fiction (also called women's fiction). These genres were the most popular novels of Stowe's time and were "written by, for, and about women" along with featuring a writing style that evoked a reader's sympathy and emotion. ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' has been called a "representative" example of a sentimental novel.

The power in this type of writing can be seen in the reaction of contemporary readers. Georgiana May, a friend of Stowe's, wrote a letter to the author, saying: "I was up last night long after one o'clock, reading and finishing ''Uncle Tom's Cabin''. I could not leave it any more than I could have left a dying child." Another reader is described as obsessing on the book at all hours and having considered renaming her daughter Eva. Evidently the death of Little Eva affected a lot of people at that time, because in 1852, 300 baby girls in Boston alone were given that name.

Despite this positive reaction from readers, for decades literary critics dismissed the style found in ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' and other sentimental novels because these books were written by women and so prominently featured what one critic called "women's sloppy emotions". Another literary critic said that had the novel not been about slavery, "it would be just another sentimental novel", and another described the book as "primarily a derivative piece of hack work". In ''The Literary History of the United States'', George F. Whicher called ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' " Sunday-school fiction", full of "broadly conceived melodrama, humor, and pathos".

In 1985 Jane Tompkins

Jane Tompkins (born 1940) is an American literary criticism, literary scholar who has worked on canon (fiction), canon formation, feminist literary criticism, and reader response criticism. She has also coined and developed the notion of cultural ...

expressed a different view with her famous defense of the book in "Sentimental Power: Uncle Tom's Cabin and the Politics of Literary History." Tompkins praised the style so many other critics had dismissed, writing that sentimental novels showed how women's emotions had the power to change the world for the better. She also said that the popular domestic novels of the 19th century, including ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'', were remarkable for their "intellectual complexity, ambition, and resourcefulness"; and that ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' offers a "critique of American society far more devastating than any delivered by better-known critics such as Hawthorne

Hawthorne often refers to the American writer Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Hawthorne may also refer to:

Places

Australia

*Hawthorne, Queensland, a suburb of Brisbane

Canada

* Hawthorne Village, Ontario, a suburb of Milton, Ontario

United States

* Hawt ...

and Melville."

Reactions to the novel

''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' has exerted an influence equaled by few other novels in history. Upon publication, ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' ignited a firestorm of protest from defenders of slavery (who created a number of books in response to the novel) while the book elicited praise from abolitionists. The novel is considered an influential "landmark" of protest literature.Contemporary reaction in United States and around the world

''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' had an "incalculable" impact on the 19th-century world and captured the imagination of many Americans. In a likely apocryphal story that alludes to the novel's impact, when

''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' had an "incalculable" impact on the 19th-century world and captured the imagination of many Americans. In a likely apocryphal story that alludes to the novel's impact, when Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

met Stowe in 1862 he supposedly commented, "So this is the little lady who started this great war." Historians are undecided if Lincoln actually said this line, and in a letter that Stowe wrote to her husband a few hours after meeting with Lincoln no mention of this comment was made. Many writers have also credited the novel with focusing Northern anger at the injustices of slavery and the Fugitive Slave Law and helping to fuel the abolitionist movement. Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

general

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

and politician James Baird Weaver

James Baird Weaver (June 12, 1833 – February 6, 1912) was a member of the United States House of Representatives and two-time candidate for President of the United States. Born in Ohio, he moved to Iowa as a boy when his family claimed a ...

said that the book convinced him to become active in the abolitionist movement.

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

was "convinced both of the social uses of the novel and of Stowe's humanitarianism" and heavily promoted the novel in his newspaper during the book's initial release. Though Douglass said ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' was "a work of marvelous depth and power," he also published criticism of the novel, most prominently by Martin Delany

Martin Robison Delany (May 6, 1812January 24, 1885) was an abolitionist, journalist, physician, soldier, and writer, and arguably the first proponent of black nationalism. Delany is credited with the Pan-African slogan of "Africa for Africans."

...

. In a series of letters in the paper, Delany accused Stowe of "borrowing (and thus profiting) from the work of black writers to compose her novel" and chastised Stowe for her "apparent support of black colonization to Africa." " Martin was "one of the most out-spoken black critics" of ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' at the time and later wrote ''Blake; or the Huts of America

''Blake; or The Huts of America'': A Tale of the Mississippi Valley, the Southern United States, and Cuba is a novel by Martin Delany, initially published in two parts: The first in 1859 by '' The Anglo-African'', and the second, during the earli ...

,'' a novel where an African American "chooses violent rebellion over Tom's resignation."

White people in the American South were outraged at the novel's release, with the book also roundly criticized by slavery supporters. Southern novelist William Gilmore Simms

William Gilmore Simms (April 17, 1806 – June 11, 1870) was an American writer and politician from the American South who was a "staunch defender" of slavery. A poet, novelist, and historian, his ''History of South Carolina'' served as the defin ...

declared the work utterly false while also calling it slanderous. Reactions ranged from a bookseller in Mobile, Alabama

Mobile ( , ) is a city and the county seat of Mobile County, Alabama, United States. The population within the city limits was 187,041 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, down from 195,111 at the 2010 United States census, 2010 cens ...

, being forced to leave town for selling the novel to threatening letters sent to Stowe (including a package containing a slave's severed ear). Many Southern writers, like Simms, soon wrote their own books in opposition to Stowe's novel.

Some critics highlighted Stowe's paucity of life-experience relating to Southern life, saying that it led her to create inaccurate descriptions of the region. For instance, she had never been to a Southern plantation. Stowe always said she based the characters of her book on stories she was told by runaway slaves in Cincinnati. It is reported that "She observed firsthand several incidents which galvanized her to write hefamous anti-slavery novel. Scenes she observed on the Ohio River, including seeing a husband and wife being sold apart, as well as newspaper and magazine accounts and interviews, contributed material to the emerging plot."

In response to these criticisms, in 1853 Stowe published ''A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin

''A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin'' is a book by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. It was published to document the veracity of the depiction of slavery in Stowe's anti-slavery novel ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' (1852). First published in 1853 by Jewet ...

'', an attempt to document the veracity of the novel's depiction of slavery. In the book, Stowe discusses each of the major characters in ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' and cites "real life equivalents" to them while also mounting a more "aggressive attack on slavery in the South than the novel itself had". Like the novel, ''A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin'' was a best-seller, but although Stowe claimed ''A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin'' documented her previously consulted sources, she actually read many of the cited works only after the publication of her novel.

''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' also created great interest in the United Kingdom. The first London edition appeared in May 1852 and sold 200,000 copies. Some of this interest was because of British antipathy to America. As one prominent writer explained, "The evil passions which ''Uncle Tom'' gratified in England were not hatred or vengeance f slavery but national jealousy and national vanity. We have long been smarting under the conceit of America—we are tired of hearing her boast that she is the freest and the most enlightened country that the world has ever seen. Our clergy hate her voluntary system—our

''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' also created great interest in the United Kingdom. The first London edition appeared in May 1852 and sold 200,000 copies. Some of this interest was because of British antipathy to America. As one prominent writer explained, "The evil passions which ''Uncle Tom'' gratified in England were not hatred or vengeance f slavery but national jealousy and national vanity. We have long been smarting under the conceit of America—we are tired of hearing her boast that she is the freest and the most enlightened country that the world has ever seen. Our clergy hate her voluntary system—our Tories

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

hate her democrats—our Whigs hate her parvenu

A ''parvenu'' is a person who is a relative newcomer to a high-ranking socioeconomic class. The word is borrowed from the French language; it is the past participle of the verb ''parvenir'' (to reach, to arrive, to manage to do something).

Orig ...

s—our Radicals hate her litigiousness, her insolence, and her ambition. All parties hailed Mrs. Stowe as a revolter from the enemy." Charles Francis Adams, the American minister to Britain during the war, argued later that "''Uncle Tom's Cabin''; or ''Life among the Lowly'', published in 1852, exercised, largely from fortuitous circumstances, a more immediate, considerable and dramatic world-influence than any other book ever printed."

Stowe sent a copy of the book to Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

, who wrote her in response: "I have read your book with the deepest interest and sympathy, and admire, more than I can express to you, both the generous feeling which inspired it, and the admirable power with which it is executed." The historian and politician Thomas Babington Macaulay

Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay, (; 25 October 1800 – 28 December 1859) was a British historian and Whig politician, who served as the Secretary at War between 1839 and 1841, and as the Paymaster-General between 1846 and 1 ...

wrote in 1852 that "it is the most valuable addition that America has made to English literature."

20th century and modern criticism

In the 20th century, a number of writers attacked ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' not only for the stereotypes the novel had created about African-Americans but also because of "the utter disdain of the Tom character by the black community. These writers included Richard Wright with his collection '' Uncle Tom's Children'' (1938) andChester Himes

Chester Bomar Himes (July 29, 1909 – November 12, 1984) was an American writer. His works, some of which have been filmed, include '' If He Hollers Let Him Go'', published in 1945, and the Harlem Detective series of novels for which he is be ...

with his 1943 short story "Heaven Has Changed". Ralph Ellison

Ralph Waldo Ellison (March 1, 1913 – April 16, 1994) was an American writer, literary critic, and scholar best known for his novel '' Invisible Man'', which won the National Book Award in 1953. He also wrote ''Shadow and Act'' (1964), a collec ...

also critiqued the book with his 1952 novel ''Invisible Man

''Invisible Man'' is a novel by Ralph Ellison, published by Random House in 1952. It addresses many of the social and intellectual issues faced by African Americans in the early twentieth century, including black nationalism, the relationship b ...

,'' with Ellison figuratively killing Uncle Tom in the opening chapter.

In 1945 James Baldwin published his influential and infamous critical essay "Everbody's Protest Novel". In the essay, Baldwin described ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' as "a bad novel, having, in its self-righteousness, virtuous sentimentality". He argued that the novel lacked psychological depth, and that Stowe, "was not so much a novelist as an impassioned pamphleteer". Edward Rothstein

Edward Benjamin Rothstein (born October 16, 1952) is an American critic. Rothstein wrote music criticism early in his career, but is best known for his critical analysis of museums and museum exhibitions.

Rothstein holds a B.A. from Yale Universi ...

has claimed that Baldwin missed the point and that the purpose of the novel was "to treat slavery not as a political issue but as an individually human one – and ultimately a challenge to Christianity itself."

George Orwell in his essay " Good Bad Books", first published in ''Tribune

Tribune () was the title of various elected officials in ancient Rome. The two most important were the tribunes of the plebs and the military tribunes. For most of Roman history, a college of ten tribunes of the plebs acted as a check on the ...

'' in November 1945, claims that "perhaps the supreme example of the 'good bad' book is ''Uncle Tom's Cabin''. It is an unintentionally ludicrous book, full of preposterous melodramatic incidents; it is also deeply moving and essentially true; it is hard to say which quality outweighs the other." But he concludes "I would back ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' to outlive the complete works of Virginia Woolf

Adeline Virginia Woolf (; ; 25 January 1882 28 March 1941) was an English writer, considered one of the most important modernist 20th-century authors and a pioneer in the use of stream of consciousness as a narrative device.

Woolf was born i ...

or George Moore, though I know of no strictly literary test which would show where the superiority lies."

The negative associations related to ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'', in particular how the novel and associated plays created and popularized racial stereotypes, have to some extent obscured the book's historical impact as a "vital antislavery tool". After the turn of the millennium, scholars such as Henry Louis Gates Jr.

Henry Louis "Skip" Gates Jr. (born September 16, 1950) is an American literary critic, professor, historian, and filmmaker, who serves as the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and Director of the Hutchins Center for African and African A ...

and Hollis Robbins

Hollis Robbins (born 1963) is an American academic and essayist; Robbins currently serves as Dean of Humanities at University of Utah. Her scholarship focuses on African-American literature.

Education and early career

Robbins was born and raised ...

have re-examined ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' in what has been called a "serious attempt to resurrect it as both a central document in American race relations and a significant moral and political exploration of the character of those relations."

Literary significance

Generally recognized as the first best-selling novel, ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' greatly influenced development of not only American literature but also protest literature in general. Later books that owe a large debt to ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' include ''The Jungle

''The Jungle'' is a 1906 novel by the American journalist and novelist Upton Sinclair. Sinclair's primary purpose in describing the meat industry and its working conditions was to advance socialism in the United States. However, most readers we ...

'' by Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American writer, muckraker, political activist and the 1934 Democratic Party nominee for governor of California who wrote nearly 100 books and other works in sever ...

and ''Silent Spring

''Silent Spring'' is an environmental science book by Rachel Carson. Published on September 27, 1962, the book documented the environmental harm caused by the indiscriminate use of pesticides. Carson accused the chemical industry of spreading d ...

'' by Rachel Carson

Rachel Louise Carson (May 27, 1907 – April 14, 1964) was an American marine biologist, writer, and conservationist whose influential book '' Silent Spring'' (1962) and other writings are credited with advancing the global environmental ...

.

Despite this undisputed significance, ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' has been called "a blend of children's fable

Fable is a literary genre: a succinct fictional story, in prose or verse (poetry), verse, that features animals, legendary creatures, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature that are Anthropomorphism, anthropomorphized, and that illustrat ...

and propaganda".

The novel has also been dismissed by several literary critics

Literary criticism (or literary studies) is the study, evaluation, and interpretation of literature. Modern literary criticism is often influenced by literary theory, which is the philosophical analysis, philosophical discussion of literature' ...

as "merely a sentimental novel"; critic George Whicher stated in his ''Literary History of the United States'' that "Nothing attributable to Mrs. Stowe or her handiwork can account for the novel's enormous vogue; its author's resources as a purveyor of Sunday-school fiction were not remarkable. She had at most a ready command of broadly conceived melodrama, humor, and pathos, and of these popular sentiments she compounded her book."

Other critics, though, have praised the novel. Edmund Wilson

Edmund Wilson Jr. (May 8, 1895 – June 12, 1972) was an American writer and literary critic who explored Freudian and Marxist themes. He influenced many American authors, including F. Scott Fitzgerald, whose unfinished work he edited for publi ...

stated that "To expose oneself in maturity to Uncle Tom's Cabin may therefore prove a startling experience. It is a much more impressive work than one has ever been allowed to suspect." Jane Tompkins stated that the novel is one of the classics of American literature and wonders if many literary critics dismiss the book because it was simply too popular during its day.

Creation and popularization of stereotypes

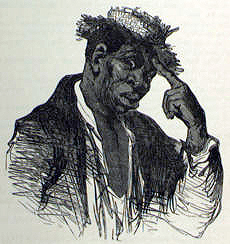

Many modern scholars and readers have criticized the book for condescending racist descriptions of the black characters' appearances, speech, and behavior, as well as the passive nature of Uncle Tom in accepting his fate. The novel's creation and use of common

Many modern scholars and readers have criticized the book for condescending racist descriptions of the black characters' appearances, speech, and behavior, as well as the passive nature of Uncle Tom in accepting his fate. The novel's creation and use of common stereotypes

In social psychology, a stereotype is a generalized belief about a particular category of people. It is an expectation that people might have about every person of a particular group. The type of expectation can vary; it can be, for example ...

about African Americans is significant because ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' was the best-selling novel in the world during the 19th century. As a result, the book (along with illustrations from the book and associated stage productions) played a major role in perpetuating and solidifying such stereotypes into the American psyche. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Black Power and Black Arts Movements attacked the novel, claiming that the character of Uncle Tom engaged in "race betrayal", and that Tom made slaves out to be worse than slave owners.

Among the stereotypes of blacks in ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' are the "happy darky" (in the lazy, carefree character of Sam); the light-skinned tragic mulatto

The tragic mulatto is a stereotypical fictional character that appeared in American literature during the 19th and 20th centuries, starting in 1837. The "tragic mulatto" is a stereotypical mixed-race person (a "mulatto"), who is assumed to be dep ...

as a sex object (in the characters of Eliza, Cassy, and Emmeline); the affectionate, dark-skinned female mammy (through several characters, including Mammy, a cook at the St. Clare plantation); the pickaninny

Pickaninny (also picaninny, piccaninny or pickinninie) is a pidgin word for a small child, possibly derived from the Portuguese ('boy, child, very small, tiny').

In North America, ''pickaninny'' is a racial slur for African American childr ...

stereotype of black children (in the character of Topsy); the Uncle Tom, an African American who is too eager to please white people. Stowe intended Tom to be a "noble hero" and a Christ-like figure who, like Jesus at his crucifixion, forgives the people responsible for his death. The false stereotype of Tom as a "subservient fool who bows down to the white man", and the resulting derogatory term "Uncle Tom", resulted from staged "Tom Shows

Tom show is a general term for any play or musical based (often only loosely) on the 1852 novel ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' by Harriet Beecher Stowe. The novel attempts to depict the harsh reality of slavery. Due to the weak copyright laws at the tim ...

", which sometimes replaced Tom's grim death with an upbeat ending where Tom causes his oppressors to see the error of their ways, and they all reconcile happily. Stowe had no control over these shows and their alteration of her story.

Anti-Tom literature

In response to ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'', writers in the Southern United States produced a number of books to rebut Stowe's novel. This so-called Anti-Tom literature generally took a pro-slavery viewpoint, arguing that the issues of slavery as depicted in Stowe's book were overblown and incorrect. The novels in this genre tended to feature a benign white patriarchal master and a pure wife, both of whom presided over childlike slaves in a benevolent extended family style plantation. The novels either implied or directly stated that African Americans were a childlike people unable to live their lives without being directly overseen by white people.

Among the most famous anti-Tom books are ''

In response to ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'', writers in the Southern United States produced a number of books to rebut Stowe's novel. This so-called Anti-Tom literature generally took a pro-slavery viewpoint, arguing that the issues of slavery as depicted in Stowe's book were overblown and incorrect. The novels in this genre tended to feature a benign white patriarchal master and a pure wife, both of whom presided over childlike slaves in a benevolent extended family style plantation. The novels either implied or directly stated that African Americans were a childlike people unable to live their lives without being directly overseen by white people.

Among the most famous anti-Tom books are ''The Sword and the Distaff

William Gilmore Simms (April 17, 1806 – June 11, 1870) was an American writer and politician from the American South who was a "staunch defender" of slavery. A poet, novelist, and historian, his ''History of South Carolina'' served as the defi ...

'' by William Gilmore Simms

William Gilmore Simms (April 17, 1806 – June 11, 1870) was an American writer and politician from the American South who was a "staunch defender" of slavery. A poet, novelist, and historian, his ''History of South Carolina'' served as the defin ...

, ''Aunt Phillis's Cabin

''Aunt Phillis's Cabin; or, Southern Life as It Is'' by Mary Henderson Eastman is a plantation fiction novel, and is perhaps the most read anti-Tom novel in American literature. It was published by Lippincott, Grambo & Co. of Philadelphia in 1 ...

'' by Mary Henderson Eastman

Mary Henderson Eastman (February 24, 1818February 24, 1887) was an American historian and novelist who is noted for her works about Native American life. She was also an advocate of slavery in the United States. In response to Harriet Beecher St ...

, and ''The Planter's Northern Bride

''The Planter's Northern Bride'' is an 1854 novel written by Caroline Lee Hentz, in response to the publication of ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' by Harriet Beecher Stowe in 1852.

Overview

Unlike other examples of anti-Tom literature (aka "plantation ...

'' by Caroline Lee Hentz

Caroline Lee Whiting Hentz (June 1, 1800, Lancaster, Massachusetts – February 11, 1856, Marianna, Florida) was an American novelist and author, most noted for her defenses of slavery and opposition to the abolitionist movement. Her widely read ...

, with the last author having been a close personal friend of Stowe's when the two lived in Cincinnati. Simms' book was published a few months after Stowe's novel, and it contains a number of sections and discussions disputing Stowe's book and her view of slavery. Hentz's 1854 novel, widely read at the time but now largely forgotten, offers a defense of slavery as seen through the eyes of a Northern woman—the daughter of an abolitionist, no less—who marries a Southern slave owner.

In the decade between the publication of ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' and the start of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, between twenty and thirty anti-Tom books were published (although others continued to be published after the war, including ''The Leopard's Spots

''The Leopard's Spots: A Romance of the White Man's Burden—1865–1900'' is the first novel of Thomas Dixon's Reconstruction trilogy, and was followed by '' The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan'' (1905), and '' The Traitor: A ...

'' in 1902 by "professional racist" Thomas Dixon Jr.). More than half of these anti-Tom books were written by white women, Simms commenting at one point about the "Seemingly poetic justice of having the Northern woman (Stowe) answered by a Southern woman."

Dramatic adaptations

Plays and Tom shows

Even though ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' was the best-selling novel of the 19th century, far more Americans of that time saw the story as a stage play or musical than read the book. Historian Eric Lott estimated that "for every one of the three hundred thousand who bought the novel in its first year, many more eventually saw the play." In 1902, it was reported that by a quarter million of these presentations had already been performed in the United States. Given the lax copyright laws of the time, stage plays based on ''Uncle Tom's Cabin''—"Tom shows"—began to appear while the novel was still being serialized. Stowe refused to authorize dramatization of her work because of her distrust of drama (although she did eventually go to see George L. Aiken's version and, according to Francis Underwood, was "delighted" by Caroline Howard's portrayal of Topsy). Aiken's stage production was the most popular play in the U.S. and England for 75 years. Stowe's refusal to authorize a particular dramatic version left the field clear for any number of adaptations, some launched for (various) political reasons and others as simply commercial theatrical ventures. Nointernational copyright

While no creative work is automatically protected worldwide, there are international treaties which provide protection automatically for all creative works as soon as they are fixed in a medium. There are two primary international copyright agreem ...

laws existed at the time. The book and plays were translated into several languages; Stowe received no money, which could have meant as much as "three-fourths of her just and legitimate wages".

All the Tom shows appear to have incorporated elements of melodrama and blackface minstrelsy. These plays varied tremendously in their politics—some faithfully reflected Stowe's sentimentalized antislavery politics, while others were more moderate, or even pro-slavery. Many of the productions featured demeaning racial caricatures of Black people; some productions also featured songs by Stephen Foster

Stephen Collins Foster (July 4, 1826January 13, 1864), known also as "the father of American music", was an American composer known primarily for his parlour and minstrel music during the Romantic period. He wrote more than 200 songs, inc ...

(including "My Old Kentucky Home

"My Old Kentucky Home, Good-Night!" is a sentimental ballad written by Stephen Foster, probably composed in 1852. It was published in January 1853 by Firth, Pond, & Co. of New York. Foster was likely inspired by Harriet Beecher Stowe's anti-sla ...

", "Old Folks at Home

"Old Folks at Home" (also known as " Swanee River") is a minstrel song written by Stephen Foster in 1851. Since 1935, it has been the official state song of Florida, although in 2008 the original lyrics were revised. It is Roud Folk Song Ind ...

", and "Massa's in the Cold Ground"). The best-known Tom shows were those of George Aiken and H.J. Conway.

The many stage variants of ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' "dominated northern popular culture... for several years" during the 19th century, and the plays were still being performed in the early 20th century.

Films

''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' has been adapted several times as a film. Most of these movies were created during the

''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' has been adapted several times as a film. Most of these movies were created during the silent film

A silent film is a film with no synchronized Sound recording and reproduction, recorded sound (or more generally, no audible dialogue). Though silent films convey narrative and emotion visually, various plot elements (such as a setting or era) ...

era (''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' was the most-filmed book of that time period). Because of the continuing popularity of both the book and "Tom" shows, audiences were already familiar with the characters and the plot, making it easier for the film to be understood without spoken words.

The first film version of ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' was one of the earliest full-length movies (although full-length at that time meant between 10 and 14 minutes). This 1903 film, directed by Edwin S. Porter

Edwin Stanton Porter (April 21, 1870 – April 30, 1941) was an American film pioneer, most famous as a producer, director, studio manager and cinematographer with the Edison Manufacturing Company and the Famous Players Film Company. Of over ...

, used white actors in blackface in the major roles and black performers only as extras. This version was evidently similar to many of the "Tom Shows" of earlier decades and featured several stereotypes about blacks (such as having the slaves dance in almost any context, including at a slave auction).

In 1910, a three-reel Vitagraph Company of America

Vitagraph Studios, also known as the Vitagraph Company of America, was a United States motion picture studio. It was founded by J. Stuart Blackton and Albert E. Smith in 1897 in Brooklyn, New York, as the American Vitagraph Company. By 1907, ...

production was directed by J. Stuart Blackton

James Stuart Blackton (January 5, 1875 – August 13, 1941) was a British-American film producer and director of the silent era. One of the pioneers of motion pictures, he founded Vitagraph Studios in 1897. He was one of the first filmmakers to ...

and adapted by Eugene Mullin. According to ''The Dramatic Mirror'', this film was "a decided innovation" in motion pictures and "the first time an American company" released a dramatic film in three reels. Until then, full-length movies of the time were 15 minutes long and contained only one reel of film. The movie starred Florence Turner, Mary Fuller

Mary Claire Fuller (October 5, 1888 – December 9, 1973) was an American actress active in both stage and silent films. She also was a screenwriter and had several films produced. An early major star, by 1917 she could no longer gain role ...

, Edwin R. Phillips, Flora Finch