USS Utah (BB-31) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

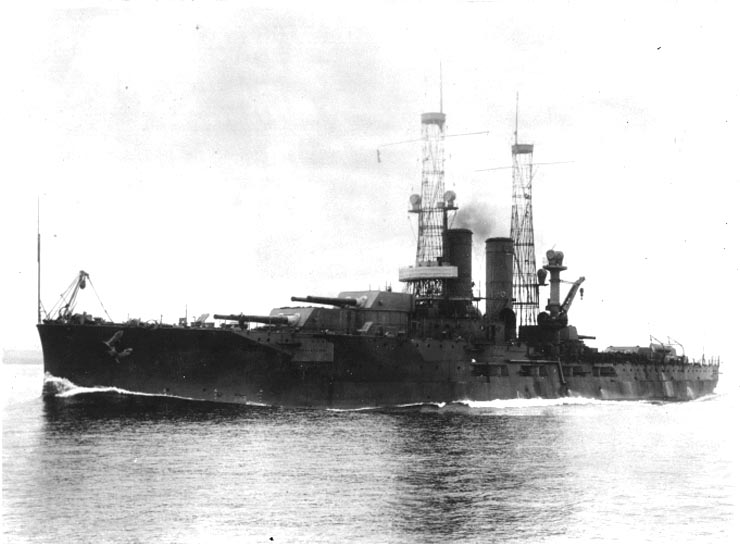

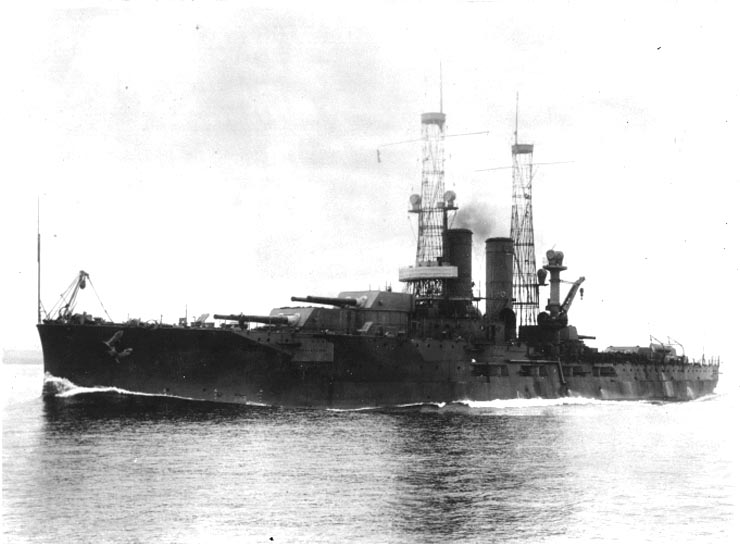

USS ''Utah'' (BB-31/AG-16) was the second and final member of the of

''Utah'' was

''Utah'' was  ''Utah'' remained off Veracruz for two months, before she returned to the New York Navy Yard for an overhaul in late June. She spent the next three years conducting the normal routine of training with the Atlantic Fleet. On 6 April 1917, the United States entered

''Utah'' remained off Veracruz for two months, before she returned to the New York Navy Yard for an overhaul in late June. She spent the next three years conducting the normal routine of training with the Atlantic Fleet. On 6 April 1917, the United States entered

''Utah'' returned to active duty on 1 December, after which she served with the Scouting Fleet. She left Hampton Roads on 21 November 1928 for another South American cruise. This time, she picked up President-elect Herbert C. Hoover and his entourage in Montevideo, and transported them to Rio de Janeiro in December, and then carried them home to the United States, arriving in Hampton Roads on 6 January 1929. According to the terms of the London Naval Treaty of 1930, ''Utah'' was converted into a radio-controlled

''Utah'' returned to active duty on 1 December, after which she served with the Scouting Fleet. She left Hampton Roads on 21 November 1928 for another South American cruise. This time, she picked up President-elect Herbert C. Hoover and his entourage in Montevideo, and transported them to Rio de Janeiro in December, and then carried them home to the United States, arriving in Hampton Roads on 6 January 1929. According to the terms of the London Naval Treaty of 1930, ''Utah'' was converted into a radio-controlled

The Navy declared ''Utah'' to be

The Navy declared ''Utah'' to be

"Oral History Interview #392, Reuben John Eichman (1919–2004), ''USS Utah,'' Survivor," 5 December 2001

"Vaessen, John (Jack) (1916–2018) — Pearl Harbor Survivor," 1 June 1987

"Pharmacist's Mate Second Class Lee Soucy [ Leonide Benoit Soucy; 1919–2010] – Oral History of The Pearl Harbor Attack,"

– published 21 September 2015, Naval History and Heritage Command

"Interview With Mr. Lee Soucy,"

7 December 2004,

dreadnought

The dreadnought (alternatively spelled dreadnaught) was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an impact when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her ...

battleships. The first ship of the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

named after the state of Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

, she had one sister ship, . ''Utah'' was built by the New York Shipbuilding Corporation

The New York Shipbuilding Corporation (or New York Ship for short) was an American shipbuilding company that operated from 1899 to 1968, ultimately completing more than 500 vessels for the U.S. Navy, the United States Merchant Marine, the United ...

, laid down in March 1909 and launched in December of that year. She was completed in August 1911, and was armed with a main battery of ten guns in five twin gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechani ...

s.

''Utah'' and ''Florida'' were the first ships to arrive during the United States occupation of Veracruz

The United States occupation of Veracruz (April 21 to November 23, 1914) began with the Battle of Veracruz and lasted for seven months. The incident came in the midst of poor diplomatic relations between Mexico and the United States, and was r ...

in 1914 during the Mexican Revolution. The two battleships sent ashore a landing party that began the occupation of the city. After the American entrance into World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, ''Utah'' was stationed at Berehaven

Castletownbere () is a town in County Cork in Ireland. It is located on the Beara Peninsula by Berehaven Harbour. It is also known as Castletown Berehaven.

A regionally important fishing port, the town also serves as a commercial and retail hub ...

in Bantry Bay

Bantry Bay ( ga, Cuan Baoi / Inbhear na mBárc / Bádh Bheanntraighe) is a bay located in County Cork, Ireland. The bay runs approximately from northeast to southwest into the Atlantic Ocean. It is approximately 3-to-4 km (1.8-to-2.5 mil ...

, Ireland, where she protected convoys from potential German surface raiders. Throughout the 1920s, the ship conducted numerous training cruises and fleet maneuvers, and carried dignitaries on tours of South America twice, in 1924 and 1928.

In 1931, ''Utah'' was demilitarized and converted into a target ship

A target ship is a vessel — typically an obsolete or captured warship — used as a seaborne target for naval gunnery practice or for weapons testing. Targets may be used with the intention of testing effectiveness of specific types of ammunit ...

and re-designated as AG-16, in accordance with the terms of the London Naval Treaty signed the previous year. She was also equipped with numerous anti-aircraft guns of different types to train gunners for the fleet. She served in these two roles for the rest of the decade, and late 1941 found the ship in Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the R ...

. She was in port on the morning of 7 December, and in the first minutes of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

, was hit by two torpedoes, which caused serious flooding. ''Utah'' quickly rolled over and sank; 58 men were killed, but the vast majority of her crew were able to escape. The wreck remains in the harbor, and in 1972, a memorial was erected near the ship.

Design

''Utah'' waslong overall

__NOTOC__

Length overall (LOA, o/a, o.a. or oa) is the maximum length of a vessel's hull measured parallel to the waterline. This length is important while docking the ship. It is the most commonly used way of expressing the size of a ship, an ...

and had a beam of and a draft

Draft, The Draft, or Draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a vesse ...

of . She displaced as designed and up to at full load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into wei ...

. The ship was powered by four-shaft Parsons

Parsons may refer to:

Places

In the United States:

* Parsons, Kansas, a city

* Parsons, Missouri, an unincorporated community

* Parsons, Tennessee, a city

* Parsons, West Virginia, a town

* Camp Parsons, a Boy Scout camp in the state of Washingt ...

steam turbines

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam turbin ...

rated at and twelve coal-fired Babcock & Wilcox

Babcock & Wilcox is an American renewable, environmental and thermal energy technologies and service provider that is active and has operations in many international markets across the globe with its headquarters in Akron, Ohio, USA. Historicall ...

boiler

A boiler is a closed vessel in which fluid (generally water) is heated. The fluid does not necessarily boil. The heated or vaporized fluid exits the boiler for use in various processes or heating applications, including water heating, centr ...

s, generating a top speed of . The ship had a cruising range of at a speed of . She had a crew of 1,001 officers and men.

The ship was armed with a main battery of ten 12-inch/45 Mark 5 guns in five twin gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechani ...

s on the centerline, two of which were placed in a superfiring pair forward. The other three turrets were placed aft of the superstructure. The secondary battery consisted of sixteen /51 guns mounted in casemates along the side of the hull. As was standard for capital ship

The capital ships of a navy are its most important warships; they are generally the larger ships when compared to other warships in their respective fleet. A capital ship is generally a leading or a primary ship in a naval fleet.

Strategic im ...

s of the period, she carried a pair of torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s, submerged in her hull on the broadside. The main armored belt was thick, while the armored deck was thick. The gun turrets had thick faces and the conning tower had thick sides.

Service history

Construction – 1922

''Utah'' was

''Utah'' was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

at the New York Shipbuilding Corporation

The New York Shipbuilding Corporation (or New York Ship for short) was an American shipbuilding company that operated from 1899 to 1968, ultimately completing more than 500 vessels for the U.S. Navy, the United States Merchant Marine, the United ...

on 15 March 1909. She was launched on 23 December 1909 and was commissioned into the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

on 31 August 1911. She then conducted a shakedown cruise that stopped in Hampton Roads, Santa Rosa Island, Pensacola

Pensacola () is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle, and the county seat and only incorporated city of Escambia County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 54,312. Pensacola is the principal ci ...

, Galveston

Galveston ( ) is a coastal resort city and port off the Southeast Texas coast on Galveston Island and Pelican Island in the U.S. state of Texas. The community of , with a population of 47,743 in 2010, is the county seat of surrounding Ga ...

, Kingston, Jamaica, and Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. She was then assigned to the Atlantic Fleet in March 1912, after which time she participated in gunnery drills. She underwent an overhaul at the New York Navy Yard starting on 16 April. ''Utah'' left New York on 1 June and proceeded to Annapolis by way of Hampton Roads, arriving on 6 June. From there, she took a crew of naval cadets from the Naval Academy

A naval academy provides education for prospective naval officers.

See also

* Military academy

A military academy or service academy is an educational institution which prepares candidates for service in the officer corps. It normally pro ...

on a midshipman training cruise off the coast of New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the Can ...

, which lasted until 25 August.

For the next two years, ''Utah'' followed a similar routine of training exercises and midshipman cruises in the Atlantic. During the period 8–30 November 1913, ''Utah'' made a goodwill cruise to European waters, which included a stop in Villefranche, France. In early 1914 during the Mexican Revolution, the United States decided to intervene in the fighting. While en route to Mexico on 16 April, ''Utah'' was ordered to intercept the German-flagged steamer , which was carrying arms to the Mexican dictator Victoriano Huerta

José Victoriano Huerta Márquez (; 22 December 1854 – 13 January 1916) was a general in the Mexican Federal Army and 39th President of Mexico, who came to power by coup against the democratically elected government of Francisco I. Madero wit ...

. ''Ypiranga''s arrival in Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

prompted the US to occupy the city; ''Utah'' and her sister ship ''Florida'' were the first American vessels on the scene. The two ships landed a combined contingent of a thousand Marines

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refle ...

and Bluejackets to begin the occupation of the city on 21 April. Over the next three days, the Marines battled rebels in the city and suffered 94 casualties, while killing hundreds of Mexicans in return.

''Utah'' remained off Veracruz for two months, before she returned to the New York Navy Yard for an overhaul in late June. She spent the next three years conducting the normal routine of training with the Atlantic Fleet. On 6 April 1917, the United States entered

''Utah'' remained off Veracruz for two months, before she returned to the New York Navy Yard for an overhaul in late June. She spent the next three years conducting the normal routine of training with the Atlantic Fleet. On 6 April 1917, the United States entered World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, declaring war on Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

over its unrestricted submarine warfare

Unrestricted submarine warfare is a type of naval warfare in which submarines sink merchant ships such as freighters and tankers without warning, as opposed to attacks per prize rules (also known as "cruiser rules") that call for warships to s ...

campaign against Britain. ''Utah'' was stationed in Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the Eastern Shore of Maryland / ...

to train engine room personnel and gunners for the rapidly expanding fleet until 30 August 1918, when she departed for Bantry Bay

Bantry Bay ( ga, Cuan Baoi / Inbhear na mBárc / Bádh Bheanntraighe) is a bay located in County Cork, Ireland. The bay runs approximately from northeast to southwest into the Atlantic Ocean. It is approximately 3-to-4 km (1.8-to-2.5 mil ...

, Ireland with Vice Admiral Henry T. Mayo, Commander-in-Chief of the Atlantic Fleet aboard. After arriving in Ireland, ''Utah'' was assigned as the flagship of Battleship Division 6 (BatDiv 6), commanded by Rear Admiral Thomas S. Rodgers. BatDiv 6 was tasked with covering convoys in the Western Approaches

The Western Approaches is an approximately rectangular area of the Atlantic Ocean lying immediately to the west of Ireland and parts of Great Britain. Its north and south boundaries are defined by the corresponding extremities of Britain. The c ...

against possible attacks from German surface raiders. ''Utah'' served in the division along with and .

Following the end of the war in November 1918, ''Utah'' visited the Isle of Portland

An isle is an island, land surrounded by water. The term is very common in British English

British English (BrE, en-GB, or BE) is, according to Lexico, Oxford Dictionaries, "English language, English as used in Great Britain, as distinct fr ...

in Britain, and escorted the liner in December, which carried President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

to Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

* Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

* Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

** Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Br ...

, France, for the post-war peace negotiations at Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, ...

. ''Utah'' left Brest on 14 December, and arrived in New York on the 25th of the month. She remained there until 30 January 1919, after which time she returned to the normal peacetime routine of fleet exercises and training cruises. On 9 July 1921, ''Utah'' departed for Europe, stopping in Lisbon, Portugal, and Cherbourg, France. After arriving, she became the flagship of American warships in Europe. She carried on in this role until she was relieved by the armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast eno ...

in October 1922.

1922–1941

''Utah'' returned to the US on 21 October, where she returned to her old post as the flagship of BatDiv 6. In early 1924, ''Utah'' took part in the Fleet Problem III maneuvers, where she and her sister ''Florida'' acted as stand-ins for the new s. Later that year, ''Utah'' was chosen to carry the US diplomatic mission to the centennial celebration of theBattle of Ayacucho

The Battle of Ayacucho ( es, Batalla de Ayacucho, ) was a decisive military encounter during the Peruvian War of Independence. This battle secured the independence of Peru and ensured independence for the rest of South America. In Peru it is co ...

, which took place on 9 December 1924. She left New York on 22 November with General of the Armies John J. Pershing aboard for a goodwill tour of South America; ''Utah'' arrived at Callao, Peru, on 9 December. At the conclusion of Pershing's tour, ''Utah'' met him at Montevideo, Uruguay, and then carried him to other ports, including Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a ...

, Brazil, La Guaira, Venezuela

La Guaira () is the capital city of the Venezuelan state of the same name (formerly named Vargas) and the country's main port. It was founded in 1577 as an outlet for Caracas, to the southeast. The town and the port were badly damaged durin ...

, and Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

, Cuba. The tour ultimately ended when ''Utah'' returned Pershing to New York on 13 March 1925. ''Utah'' conducted midshipman training cruises over the summer of 1925. She was decommissioned at the Boston Navy Yard

The Boston Navy Yard, originally called the Charlestown Navy Yard and later Boston Naval Shipyard, was one of the oldest shipbuilding facilities in the United States Navy. It was established in 1801 as part of the recent establishment of t ...

on 31 October 1925, and placed in drydock for modernization. The modernization replaced her coal-fired boilers with new oil-fired models, and her aft cage mast

Lattice masts, or cage masts, or basket masts, are a type of observation Mast (sailing), mast common on United States Navy major warships in the early 20th century. They are a type of hyperboloid structure, whose weight-saving design was invented ...

was replaced with a pole mast. She was reboilered with four White-Forster oil-fired models that had been removed from the battleships and battlecruisers scrapped as a result of the Washington Naval Treaty

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, was a treaty signed during 1922 among the major Allies of World War I, which agreed to prevent an arms race by limiting naval construction. It was negotiated at the Washington Nav ...

. ''Utah'' also had a catapult mounted on her Number 3 turret along with cranes for handling the floatplanes.

''Utah'' returned to active duty on 1 December, after which she served with the Scouting Fleet. She left Hampton Roads on 21 November 1928 for another South American cruise. This time, she picked up President-elect Herbert C. Hoover and his entourage in Montevideo, and transported them to Rio de Janeiro in December, and then carried them home to the United States, arriving in Hampton Roads on 6 January 1929. According to the terms of the London Naval Treaty of 1930, ''Utah'' was converted into a radio-controlled

''Utah'' returned to active duty on 1 December, after which she served with the Scouting Fleet. She left Hampton Roads on 21 November 1928 for another South American cruise. This time, she picked up President-elect Herbert C. Hoover and his entourage in Montevideo, and transported them to Rio de Janeiro in December, and then carried them home to the United States, arriving in Hampton Roads on 6 January 1929. According to the terms of the London Naval Treaty of 1930, ''Utah'' was converted into a radio-controlled target ship

A target ship is a vessel — typically an obsolete or captured warship — used as a seaborne target for naval gunnery practice or for weapons testing. Targets may be used with the intention of testing effectiveness of specific types of ammunit ...

, to replace the older . On 1 July 1931, ''Utah'' was accordingly redesignated "AG-16". All of her primary and secondary weapons were removed, though her turrets were still mounted. The plane handling equipment was removed along with the torpedo blisters that were added in 1925. Work was completed by 1 April 1932, when she was recommissioned.

On 7 April, ''Utah'' left Norfolk for sea trial

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a " shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and ...

s to train her engine room crew and to test the radio-control equipment. The ship could be controlled at varying rates of speed and changes of course: maneuvers that a ship would conduct in battle. Her electric motors, operated by signals from the controlling ship, opened and closed throttle valves, moved her steering gear, and regulated the supply of oil to her boilers. In addition, a Sperry gyro pilot kept the ship on course. She passed her radio control trials on 6 May, and on 1 June, the ship was operated for 3 hours under radio control. On 9 June, she again left Norfolk, bound for San Pedro, Los Angeles, where she joined Training Squadron 1, Base Force, United States Fleet

The United States Fleet was an organization in the United States Navy from 1922 until after World War II. The acronym CINCUS, pronounced "sink us", was used for Commander in Chief, United States Fleet. This was replaced by COMINCH in December 1941 ...

. Starting in late July, the ship began her first round of target duty, first for the cruisers of the Pacific Fleet, and then for the battleship ''Nevada''. She continued in this role for the next nine years; she participated in Fleet Problem XVI in May 1935, during which she served as a transport for a contingent of Marines. In June, the ship was modified to train anti-aircraft gunners in addition to her target ship duties. To perform this task, she was equipped with a new /75 caliber anti-aircraft gun in a quadruple mount for experimental testing and development of the new type of weapon.

''Utah'' returned to the Atlantic to participate in Fleet Problem XX The Fleet Problems are a series of naval exercises of the United States Navy conducted in the interwar period, and later resurrected by Pacific Fleet around 2014.

The first twenty-one Fleet Problems — labeled with roman numerals as Fleet Proble ...

in January 1939, and at the end of the year, she trained with Submarine Squadron 6. She then returned to the Pacific, arriving in Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the R ...

on 1 August 1940. There, she conducted anti-aircraft gunnery training until 14 December, when she departed for Long Beach, California

Long Beach is a city in Los Angeles County, California. It is the 42nd-most populous city in the United States, with a population of 466,742 as of 2020. A charter city, Long Beach is the seventh-most populous city in California.

Incorporate ...

, arriving on 21 December. There, she served as a bombing target for aircraft from the carriers , , and . She returned to Pearl Harbor on 1 April 1941, where she resumed anti-aircraft gunnery training. She cruised to Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, largest city in the U.S. state, state of California and the List of United States cities by population, sec ...

on 20 May to carry a contingent of Marines from the Fleet Marine Force

The United States Fleet Marine Forces (FMF) are combined general- and special-purpose forces within the United States Department of the Navy that perform offensive amphibious or expeditionary warfare and defensive maritime employment. The Flee ...

to Bremerton, Washington

Bremerton is a city in Kitsap County, Washington. The population was 37,729 at the 2010 census and an estimated 41,405 in 2019, making it the largest city on the Kitsap Peninsula. Bremerton is home to Puget Sound Naval Shipyard and the Bremer ...

, after which she entered the Puget Sound Navy Yard

Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, officially Puget Sound Naval Shipyard and Intermediate Maintenance Facility (PSNS & IMF), is a United States Navy shipyard covering 179 acres (0.7 km2) on Puget Sound at Bremerton, Washington in uninterrupted u ...

on 31 May, where she was overhauled. She was equipped with new /38 cal dual-purpose gun

A dual-purpose gun is a naval artillery mounting designed to engage both surface and air targets.

Description

Second World War-era capital ships had four classes of artillery: the heavy main battery, intended to engage opposing battleships and ...

s in single mounts to improve her ability to train anti-aircraft gunners. She left Puget Sound on 14 September, bound for Pearl Harbor, where she resumed her normal duties through the rest of the year.

Attack on Pearl Harbor

In early December 1941, ''Utah'' was moored offFord Island

Ford Island ( haw, Poka Ailana) is an islet in the center of Pearl Harbor, Oahu, in the U.S. state of Hawaii. It has been known as Rabbit Island, Marín's Island, and Little Goats Island, and its native Hawaiian name is ''Mokuumeume''. The is ...

in berth F-11, after having completed another round of anti-aircraft gunnery training. Shortly before 08:00 on the morning of 7 December, some crewmen aboard ''Utah'' observed the first Japanese planes approaching to attack Pearl Harbor, but they assumed they were American aircraft. The Japanese began their attack shortly thereafter, the first bombs falling near a seaplane ramp on the southern tip of Ford Island. At the same time sixteen Nakajima B5N

The Nakajima B5N ( ja, 中島 B5N, Allied reporting name "Kate") was the standard carrier-based torpedo bomber of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) for much of World War II.

Although the B5N was substantially faster and more capable than its Al ...

torpedo bombers from the Japanese aircraft carriers and flew over Pearl City approaching the west side of Ford Island. The torpedo bombers were looking for American aircraft carriers, which usually anchored where ''Utah'' was moored that morning. The flight leaders identified ''Utah'' and rejected her as a target, deciding instead to attack 1010 Dock. However six of the B5Ns from ''Soryu'' led by Lieutenant Nakajima Tatsumi broke off to attack ''Utah'', not recognizing that the shapes over the barbettes were not turrets, but boxes covering empty holes. Six torpedoes were launched against ''Utah'', two of them struck the battleship while another missed and hit the cruiser .

Serious flooding started to quickly overwhelm ''Utah'' and she began to list to port and settle by the stern. As the crew began to abandon ship, one man—Chief Watertender Peter Tomich

Petar Herceg-Tonić (later anglicized as Peter Tomich; June 3, 1893 – December 7, 1941) was a United States Navy sailor of Herzegovinian Croat descent who received the United States military's highest award, the Medal of Honor, for his acti ...

—remained below decks to ensure as many men as possible could escape, and to keep vital machinery running as long as possible; he received the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valo ...

posthumously for his actions. At 08:12, ''Utah'' rolled over onto her side, while those crew members who had managed to escape swam to shore. Almost immediately after reaching shore, the ship's senior officer on board, Commander Solomon Isquith, heard knocking from men trapped in the capsized ship. He called for volunteers to secure a cutting torch from the badly damaged cruiser ''Raleigh'' and attempt to free trapped men; they succeeded in rescuing four men. In total, 58 officers and men were killed, though 461 survived.

Salvage

The Navy declared ''Utah'' to be

The Navy declared ''Utah'' to be in ordinary

''In ordinary'' is an English phrase with multiple meanings. In relation to the Royal Household, it indicates that a position is a permanent one. In naval matters, vessels "in ordinary" (from the 17th century) are those out of service for repair o ...

on 29 December, and she was placed under the authority of the Pearl Harbor Base Force. Following the successful righting (rotation to upright) of the capsized

Capsizing or keeling over occurs when a boat or ship is rolled on its side or further by wave action, instability or wind force beyond the angle of positive static stability or it is upside down in the water. The act of recovering a vessel fro ...

''Oklahoma'', an attempt was made to right the ''Utah'' by the same parbuckling

Parbuckle salvage, or ''parbuckling'', is the righting of a sunken vessel using rotational leverage. A common operation with smaller watercraft, parbuckling is also employed to right large vessels. In 1943, the was rotated nearly 180 degrees to ...

method using 17 winches. As ''Utah'' was rotated, she did not grip the harbor bottom, and slid towards Ford Island. The ''Utah'' recovery effort was abandoned, with ''Utah'' rotated 38 degrees from horizontal.

As abandoned, ''Utah'' cleared her berth. There was no further attempt to refloat her; unlike the battleships sunk at Battleship Row, she had no military value. She was formally placed out of commission on 5 September 1944, and then stricken from the Naval Vessel Register

The ''Naval Vessel Register'' (NVR) is the official inventory of ships and service craft in custody of or titled by the United States Navy. It contains information on ships and service craft that make up the official inventory of the Navy from t ...

on 13 November. ''Utah'' received one battle star for her brief service during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. Her rusting hulk remains in Pearl Harbor, partially above water; the men killed when ''Utah'' sank were never removed from the wreck, and as such, she is considered a war grave

A war grave is a burial place for members of the armed forces or civilians who died during military campaigns or operations.

Definition

The term "war grave" does not only apply to graves: ships sunk during wartime are often considered to b ...

.

Memorial

Around 1950, two memorials were placed at the wreck dedicated to the men in the ship's crew who were killed in the attack on Pearl Harbor. The first is a plaque on the wharf to the north of the ship, and the second is a plaque that was placed on the ship itself. In 1972, a larger memorial was erected just off Ford Island, near the sunken wreck, and is now part ofPearl Harbor National Memorial

Pearl Harbor National Memorial is a unit of the National Park System of the United States on the island of Oahu, Hawaii. The John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act removed the site from the World War II Valor in the Pac ...

. The memorial consists of a walkway made of white concrete, which extends from Ford Island out to a platform in front of the ship, where a brass plaque and a flagpole are located. The memorial is on the northwest side of Ford Island and is accessible only to individuals with military identification. A color guard

In military organizations, a colour guard (or color guard) is a detachment of soldiers assigned to the protection of regimental colours and the national flag. This duty is so prestigious that the military colour is generally carried by a young ...

stands watch over the wreck. On 9 July 1988, ''Utah'' and , the other remaining wreck in the harbor, were nominated to be added to the National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places listed ...

registry. Both wrecks were added to the list on 5 May 1989. As of 2008, seven former crewmen who were aboard ''Utah'' at the time of her sinking have been cremated and had their ashes interred in the wreck.

Relics from the ship are also preserved in the Utah State Capitol building; among the items on display are pieces from the ship's silver service and the captain's clock. The ship's bell was on display at the University of Utah

The University of Utah (U of U, UofU, or simply The U) is a public research university in Salt Lake City, Utah. It is the flagship institution of the Utah System of Higher Education. The university was established in 1850 as the University of De ...

near the entrance of the Naval Science Building from the 1960s until 2016, when it was loaned to the Naval War College

The Naval War College (NWC or NAVWARCOL) is the staff college and "Home of Thought" for the United States Navy at Naval Station Newport in Newport, Rhode Island. The NWC educates and develops leaders, supports defining the future Navy and associ ...

. It was then sent to the Naval History and Heritage Command in Richmond, Virginia for conservation work. With the bell restored, it was returned to the University of Utah on 7 December 2017 and is currently on display inside the Naval Science Building.

Notes

Footnotes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* *Selected oral histories

*"Oral History Interview #392, Reuben John Eichman (1919–2004), ''USS Utah,'' Survivor," 5 December 2001

"Vaessen, John (Jack) (1916–2018) — Pearl Harbor Survivor," 1 June 1987

U.S. Naval Institute

The United States Naval Institute (USNI) is a private Nonprofit organization, non-profit military association that offers independent, nonpartisan forums for debate of national security issues. In addition to publishing magazines and books, the ...

.

*

"Pharmacist's Mate Second Class Lee Soucy [ Leonide Benoit Soucy; 1919–2010] – Oral History of The Pearl Harbor Attack,"

– published 21 September 2015, Naval History and Heritage Command

"Interview With Mr. Lee Soucy,"

7 December 2004,

National Museum of the Pacific War

The National Museum of the Pacific War is located in Fredericksburg, Texas, the boyhood home of Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz. Nimitz served as commander in chief, United States Pacific Fleet (CinCPAC), and was soon afterward named commander i ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Utah (BB-31)

Florida-class battleships

World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument

Ships built by New York Shipbuilding Corporation

1909 ships

World War I battleships of the United States

World War II auxiliary ships of the United States

Ships present during the attack on Pearl Harbor

Ships sunk during the attack on Pearl Harbor

Maritime incidents in December 1941

World War II shipwrecks in the Pacific Ocean

Shipwrecks of Hawaii

Shipwrecks on the National Register of Historic Places in Hawaii

Military facilities on the National Register of Historic Places in Hawaii

National Historic Landmarks in Hawaii

Symbols of Utah

Battleships sunk by aircraft

Artificial reefs

World War II on the National Register of Historic Places in Hawaii

National Register of Historic Places in Honolulu County, Hawaii