USS Oklahoma (BB-37) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

USS ''Oklahoma'' (BB-37) was a built by the

''Oklahoma'' was the second of two s. Both were ordered in a naval appropriation act on 4 March 1911. She was the latest in a series of 22 battleships and seven

''Oklahoma'' was the second of two s. Both were ordered in a naval appropriation act on 4 March 1911. She was the latest in a series of 22 battleships and seven

On the night of 19 July 1915, large fires were discovered underneath the fore

On the night of 19 July 1915, large fires were discovered underneath the fore

''Oklahoma'' left for Portland on 26 November, joined there by on 30 November, ''Nevada'' on 4 December, and Battleship Division Nine's ships shortly after. The ships were assigned as a convoy escort for the

''Oklahoma'' left for Portland on 26 November, joined there by on 30 November, ''Nevada'' on 4 December, and Battleship Division Nine's ships shortly after. The ships were assigned as a convoy escort for the  ''Oklahoma'' rejoined the Scouting Fleet for exercises in the Caribbean, then returned to the West Coast in June 1930, for fleet operations through spring 1936. That summer, she carried midshipmen on a European training cruise, visiting northern ports. The cruise was interrupted by the outbreak of civil war in Spain. ''Oklahoma'' sailed to

''Oklahoma'' rejoined the Scouting Fleet for exercises in the Caribbean, then returned to the West Coast in June 1930, for fleet operations through spring 1936. That summer, she carried midshipmen on a European training cruise, visiting northern ports. The cruise was interrupted by the outbreak of civil war in Spain. ''Oklahoma'' sailed to

On 7 December 1941, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, ''Oklahoma'' was moored in berth Fox 5, on

On 7 December 1941, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, ''Oklahoma'' was moored in berth Fox 5, on

''Oklahoma'' was decommissioned on 1 September 1944, and all remaining armaments and superstructure were then removed. She was then put up for auction at the

''Oklahoma'' was decommissioned on 1 September 1944, and all remaining armaments and superstructure were then removed. She was then put up for auction at the

During dredging operations in 2006, the US Navy recovered a part of ''Oklahoma'' from the bottom of Pearl Harbor. The Navy believes it to be a portion of the port side rear fire control tower support mast. It was flown to

During dredging operations in 2006, the US Navy recovered a part of ''Oklahoma'' from the bottom of Pearl Harbor. The Navy believes it to be a portion of the port side rear fire control tower support mast. It was flown to

Maritimequest USS ''Oklahoma'' BB-37 Photo Gallery

2003: Survivors dedicate Pearl Harbor USS ''Oklahoma'' Memorial highway

*

USS ''Oklahoma'' (BB-37) Official Web Site

{{DEFAULTSORT:Oklahoma (BB-37) Nevada-class battleships Ships built by New York Shipbuilding Corporation 1914 ships Maritime incidents in 1915 Ship fires World War I battleships of the United States World War II battleships of the United States Ships present during the attack on Pearl Harbor Ships sunk during the attack on Pearl Harbor Shipwrecks of Hawaii Battleships sunk by aircraft Monuments and memorials in Hawaii Maritime incidents in 1947 World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument Maritime incidents in December 1941

New York Shipbuilding Corporation

The New York Shipbuilding Corporation (or New York Ship for short) was an American shipbuilding company that operated from 1899 to 1968, ultimately completing more than 500 vessels for the U.S. Navy, the United States Merchant Marine, the United ...

for the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

, notable for being the first American class of oil-burning dreadnoughts

The dreadnought (alternatively spelled dreadnaught) was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an impact when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her ...

.

Commissioned in 1916, ''Oklahoma'' served in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

as a part of Battleship Division Six, protecting Allied convoys on their way across the Atlantic. After the war, she served in both the United States Battle Fleet and Scouting Fleet

The Scouting Fleet was created in 1922 as part of a major, post- World War I reorganization of the United States Navy. The Atlantic and Pacific fleets, which comprised a significant portion of the ships in the United States Navy, were combined int ...

. ''Oklahoma'' was modernized between 1927 and 1929. In 1936, she rescued American citizens and refugees from the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

. On returning to the West Coast in August of the same year, ''Oklahoma'' spent the rest of her service in the Pacific.

On 7 December 1941, during the Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

, several torpedoes from torpedo-bomber airplanes hit the ''Oklahomas hull and the ship capsized. A total of 429 crew died; survivors jumped off the ship into burning hot water or crawled across mooring lines that connected ''Oklahoma'' and . Some sailors inside escaped when rescuers drilled holes and opened hatches to rescue them. In 1943, ''Oklahoma'' was righted and salvaged. Unlike most of the other battleships that were recovered following Pearl Harbor, ''Oklahoma'' was too damaged to return to duty. Her wreck was eventually stripped of her remaining armament and superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

before being sold for scrap

Scrap consists of recyclable materials, usually metals, left over from product manufacturing and consumption, such as parts of vehicles, building supplies, and surplus materials. Unlike waste, scrap has monetary value, especially recovered m ...

in 1946. The hulk

The Hulk is a superhero appearing in American comic books published by Marvel Comics. Created by writer Stan Lee and artist Jack Kirby, the character first appeared in the debut issue of ''The Incredible Hulk (comic book), The Incredible Hulk' ...

sank in a storm in 1947, while being towed from Oahu

Oahu () ( Hawaiian: ''Oʻahu'' ()), also known as "The Gathering Place", is the third-largest of the Hawaiian Islands. It is home to roughly one million people—over two-thirds of the population of the U.S. state of Hawaii. The island of O ...

, Hawaii, to a breakers yard in San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay is a large tidal estuary in the U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the big cities of San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland.

San Francisco Bay drains water f ...

.

Design

''Oklahoma'' was the second of two s. Both were ordered in a naval appropriation act on 4 March 1911. She was the latest in a series of 22 battleships and seven

''Oklahoma'' was the second of two s. Both were ordered in a naval appropriation act on 4 March 1911. She was the latest in a series of 22 battleships and seven armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast eno ...

s ordered by the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

between 1900 and 1911. The ''Nevada''-class ships were the first of the US Navy's Standard-type battleship

The Standard-type battleship was a series of twelve battleships across five classes ordered for the United States Navy between 1911 and 1916 and commissioned between 1916 and 1923. These were considered super-dreadnoughts, with the ships of the ...

s, of which 12 were completed by 1923. With these ships, the Navy created a fleet of modern battleships similar in long-range gunnery, speed, turning radius, and protection. Significant improvements, however, were made in the Standard type ships as naval technology progressed. The main innovations were triple turrets and all-or-nothing protection. The triple turrets

Turret may refer to:

* Turret (architecture), a small tower that projects above the wall of a building

* Gun turret, a mechanism of a projectile-firing weapon

* Objective turret, an indexable holder of multiple lenses in an optical microscope

* M ...

reduced the length of the ship that needed protection by placing 10 guns in four turrets instead of five, thus allowing thicker armor. The ''Nevada''-class ships were also the first US battleships with oil-fired instead of coal-fired

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when dea ...

boilers

A boiler is a closed vessel in which fluid (generally water) is heated. The fluid does not necessarily boil. The heated or vaporized fluid exits the boiler for use in various processes or heating applications, including water heating, central ...

, oil having more recoverable energy per ton than coal, thus increasing the ships' range. ''Oklahoma'' differed from her sister in being fitted with triple-expansion steam engine

A compound steam engine unit is a type of steam engine where steam is expanded in two or more stages.

A typical arrangement for a compound engine is that the steam is first expanded in a high-pressure ''(HP)'' cylinder, then having given up ...

s, a much older technology than ''Nevada''s new geared turbines

A turbine ( or ) (from the Greek , ''tyrbē'', or Latin ''turbo'', meaning vortex) is a rotary mechanical device that extracts energy from a fluid flow and converts it into useful Work (physics), work. The work produced by a turbine can be used ...

.

As constructed, she had a standard displacement

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into wei ...

of and a full-load displacement

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into wei ...

of . She was in length overall

__NOTOC__

Length overall (LOA, o/a, o.a. or oa) is the maximum length of a vessel's hull measured parallel to the waterline. This length is important while docking the ship. It is the most commonly used way of expressing the size of a ship, and ...

, at the waterline, and had a beam of and a draft

Draft, The Draft, or Draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a vesse ...

of .

She was powered by 12 oil-fired Babcock & Wilcox boiler

A high pressure watertube boiler (also spelled water-tube and water tube) is a type of boiler in which water circulates in tubes heated externally by the fire. Fuel is burned inside the furnace, creating hot gas which boils water in the steam-gen ...

s driving two dual-acting, vertical triple-expansion steam engines, which provided for a maximum speed of . She had a designed range of at .

As built, the armor on ''Oklahoma'' consisted of belt armor

Belt armor is a layer of heavy metal armor plated onto or within the outer hulls of warships, typically on battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers, and aircraft carriers.

The belt armor is designed to prevent projectiles from penetrating to ...

from thick. Deck armor was thick with a second deck, and turret armor was or on the face, on the top, on the sides, and on the rear. Armor on her barbettes

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protecti ...

was 13.5 inches. Her conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armored, from which an officer in charge can conn the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for the ship's engine, rudder, lines, and gro ...

was protected by 16 inches of armor, with 8 inches of armor on its roof.

Her armament consisted of ten /45 caliber guns, arranged in two triple and two twin mounts. As built, she also carried 21 /51 caliber guns, primarily for defense against destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed ...

s and torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

s. She also had two (some references say four) torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s for the Bliss-Leavitt Mark 3 torpedo

The Bliss-Leavitt Mark 3 torpedo was a Bliss-Leavitt torpedo adopted by the United States Navy in 1906 for use in an anti-surface ship role.

Characteristics

The Bliss-Leavitt Mark 3 was very similar to the Bliss-Leavitt Mark 2 torpedo. The prim ...

. Her crew consisted of 864 officers and enlisted men.

Service history

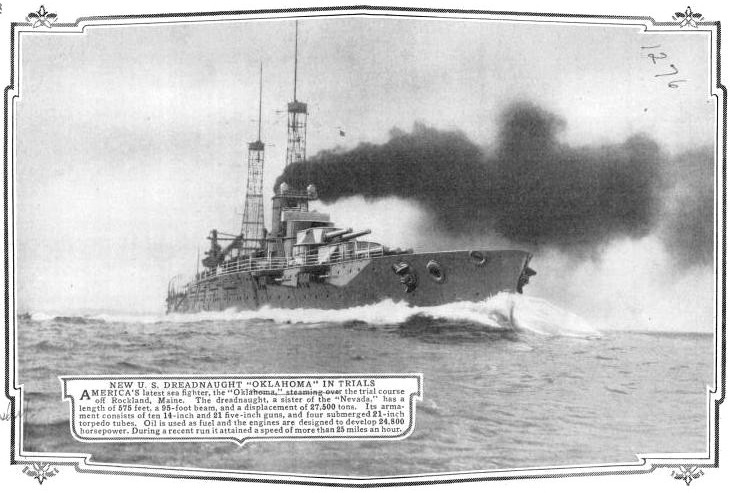

Construction

''Oklahoma''skeel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element on a vessel. On some sailboats, it may have a hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose, as well. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in the construction of a ship, in Br ...

was laid down on 26 October 1912, by the New York Shipbuilding Corporation

The New York Shipbuilding Corporation (or New York Ship for short) was an American shipbuilding company that operated from 1899 to 1968, ultimately completing more than 500 vessels for the U.S. Navy, the United States Merchant Marine, the United ...

of Camden, New Jersey, which bid $5,926,000 to construct the ship. By 12 December 1912, she was 11.2% complete, and by 13 July 1913, she was at 33%.

She was launched on 23 March 1914, sponsored by Lorena J. Cruce, daughter of Oklahoma Governor

The governor of Oklahoma is the head of government of the U.S. state of Oklahoma. Under the Oklahoma Constitution, the governor serves as the head of the Oklahoma executive branch, of the government of Oklahoma. The governor is the ''ex officio ...

Lee Cruce

Lee Cruce (July 8, 1863 – January 16, 1933) was an American lawyer, banker and the second governor of Oklahoma. Losing to Charles N. Haskell in the 1907 Democratic primary election to serve as the first governor of Oklahoma, Cruce successful ...

. The launch was preceded by an invocation

An invocation (from the Latin verb ''invocare'' "to call on, invoke, to give") may take the form of:

*Supplication, prayer or spell.

*A form of possession.

*Command or conjuration.

* Self-identification with certain spirits.

These forms ...

, the first for an American warship in half a century, given by Elijah Embree Hoss

Elijah Embree Hoss, Sr (April 14, 1849 – April 23, 1919) was an American bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, elected in 1902. He also distinguished himself as a Methodist pastor, as a college professor and administrator, and a ...

, and was attended by various dignitaries from Oklahoma and the federal government. She was subsequently moved to a dock near the new Argentine

Argentines (mistakenly translated Argentineans in the past; in Spanish (masculine) or (feminine)) are people identified with the country of Argentina. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Argentines, ...

battleship and Chinese cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several roles.

The term "cruiser", which has been in use for several ...

''Fei Hung'', soon to be the Greek , for fitting-out

Fitting out, or outfitting, is the process in shipbuilding that follows the float-out/launching of a vessel and precedes sea trials. It is the period when all the remaining construction of the ship is completed and readied for delivery to her o ...

.

main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a gun or group of guns, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, this came to be turreted ...

turret, the third to flare up on an American battleship in less than a month. However, by 22 July, the Navy believed that the ''Oklahoma'' fire had been caused by "defective insulation" or a mistake made by a dockyard worker. The fire delayed the battleship's completion so much that ''Nevada'' was able to conduct her sea trials

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a "shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and i ...

and be commissioned before ''Oklahoma''. On 23 October 1915, she was 98.1 percent complete. She was commissioned at Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

, on 2 May 1916, with Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Roger Welles in command.

World War I

Following commissioning, the ship remained along the East Coast of the United States, primarily visiting various Navy yards. At first, she was unable to join the Battleship Division Nine task force sent to support theGrand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the F ...

in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian ...

during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

because oil was unavailable there. In 1917, she underwent a refit, with two /50 caliber guns being installed forward of the mainmast for antiaircraft

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based, ...

defense and nine of the 5-inch/51 caliber guns being removed or repositioned. While conditions on the ship were cramped, the sailors on the ship had many advantages for education available to them. They also engaged in athletic competitions, including boxing

Boxing (also known as "Western boxing" or "pugilism") is a combat sport in which two people, usually wearing protective gloves and other protective equipment such as hand wraps and mouthguards, throw punches at each other for a predetermined ...

, wrestling

Wrestling is a series of combat sports involving grappling-type techniques such as clinch fighting, throws and takedowns, joint locks, pins and other grappling holds. Wrestling techniques have been incorporated into martial arts, combat s ...

, and rowing

Rowing is the act of propelling a human-powered watercraft using the sweeping motions of oars to displace water and generate reactional propulsion. Rowing is functionally similar to paddling, but rowing requires oars to be mechanically ...

competitions with the crews of the battleship and the tug . The camaraderie built from these small competitions led to fleet-wide establishment of many athletic teams pitting crews against one another for morale by the 1930s.

On 13 August 1918, ''Oklahoma'' was assigned to Battleship Division Six under the command of Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star " admiral" rank. It is often rega ...

Thomas S. Rodgers

Rear Admiral Thomas Slidell Rodgers (18 August 1858 – 28 February 1931) was an officer in the United States Navy who served during the Spanish–American War and World War I.

Biography

Born at Morristown, New Jersey, Rodgers was a scion of one ...

, and departed for Europe alongside ''Nevada''. On 23 August, they met with destroyers , , , , , and , west of Ireland, before steaming for Berehaven

Castletownbere () is a town in County Cork in Ireland. It is located on the Beara Peninsula by Berehaven Harbour. It is also known as Castletown Berehaven.

A regionally important fishing port, the town also serves as a commercial and retail hub ...

, where they waited for 18 days before battleship arrived. The division remained at anchor, tasked to protect American convoys coming into the area, but was only called out of the harbor once in 80 days. On 14 October 1918, while under command of Charles B. McVay Jr., she escorted troop ships into port at the United Kingdom, returning on 16 October. For the rest of the time, the ship conducted drills at anchor or in nearby Bantry Bay

Bantry Bay ( ga, Cuan Baoi / Inbhear na mBárc / Bádh Bheanntraighe) is a bay located in County Cork, Ireland. The bay runs approximately from northeast to southwest into the Atlantic Ocean. It is approximately 3-to-4 km (1.8-to-2.5 mil ...

. To pass the time, the crews played American football

American football (referred to simply as football in the United States and Canada), also known as gridiron, is a team sport played by two teams of eleven players on a rectangular field with goalposts at each end. The offense, the team wi ...

, and competitive sailing. ''Oklahoma'' suffered six casualties between 21 October and 2 November to the 1918 flu pandemic

The 1918–1920 influenza pandemic, commonly known by the misnomer Spanish flu or as the Great Influenza epidemic, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. The earliest documented case was ...

. ''Oklahoma'' remained off Berehaven until the end of the war on 11 November 1918. Shortly thereafter, several ''Oklahoma'' crewmembers were involved in a series of fights with members of Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Gr ...

, forcing the ship's commander to apologize and financially compensate two town mayors.

Interwar period

''Oklahoma'' left for Portland on 26 November, joined there by on 30 November, ''Nevada'' on 4 December, and Battleship Division Nine's ships shortly after. The ships were assigned as a convoy escort for the

''Oklahoma'' left for Portland on 26 November, joined there by on 30 November, ''Nevada'' on 4 December, and Battleship Division Nine's ships shortly after. The ships were assigned as a convoy escort for the ocean liner

An ocean liner is a passenger ship primarily used as a form of transportation across seas or oceans. Ocean liners may also carry cargo or mail, and may sometimes be used for other purposes (such as for pleasure cruises or as hospital ships).

Ca ...

, carrying President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

, and arrived with that ship in France several days later. She departed 14 December, for New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, and then spent early 1919 conducting winter battle drills off the coast of Cuba. On 15 June 1919, she returned to Brest, escorting Wilson on a second trip, and returned to New York, on 8 July. A part of the Atlantic Fleet for the next two years, ''Oklahoma'' was overhauled and her crew trained. The secondary battery was reduced from 20 to 12 5-inch/51 caliber guns in 1918. Early in 1921, she voyaged to South America's West Coast for combined exercises

Exercise is a body activity that enhances or maintains physical fitness and overall health and wellness.

It is performed for various reasons, to aid growth and improve strength, develop muscles and the cardiovascular system, hone athletic s ...

with the Pacific Fleet, and returned later that year for the Peruvian Centennial.

She then joined the Pacific Fleet and, in 1925, began a high-profile training cruise with several other battleships. They left San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

on 15 April 1925, arrived in Hawaii, on 27 April, where they conducted war games. They left for Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands ( Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands ( Manono and Apolima); ...

, on 1 July, crossing the equator on 6 July. On 27 July, they arrived in Australia and conducted a number of exercises there, before spending time in New Zealand, returning to the United States later that year. In early 1927, she transited the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a condui ...

and moved to join the Scouting Fleet

The Scouting Fleet was created in 1922 as part of a major, post- World War I reorganization of the United States Navy. The Atlantic and Pacific fleets, which comprised a significant portion of the ships in the United States Navy, were combined int ...

.

In November 1927, she entered the Philadelphia Navy Yard

The Philadelphia Naval Shipyard was an important naval shipyard of the United States for almost two centuries.

Philadelphia's original navy yard, begun in 1776 on Front Street and Federal Street in what is now the Pennsport section of the ci ...

for an extensive overhaul. She was modernized by adding eight 5-inch/25 cal guns, and her turrets' maximum elevation was raised from 15 to 30 degrees. An aircraft catapult

An aircraft catapult is a device used to allow aircraft to take off from a very limited amount of space, such as the deck of a vessel, but can also be installed on land-based runways in rare cases. It is now most commonly used on aircraft carrier ...

was installed atop turret No.3. She was also substantially up-armored between September 1927 and July 1929, with anti-torpedo bulges

The anti-torpedo bulge (also known as an anti-torpedo blister) is a form of defence against naval torpedoes occasionally employed in warship construction in the period between the First and Second World Wars. It involved fitting (or retrofitt ...

added, as well as an additional of steel on her armor deck. The overhaul increased her beam to , the widest in the US Navy, and reduced her speed to .

''Oklahoma'' rejoined the Scouting Fleet for exercises in the Caribbean, then returned to the West Coast in June 1930, for fleet operations through spring 1936. That summer, she carried midshipmen on a European training cruise, visiting northern ports. The cruise was interrupted by the outbreak of civil war in Spain. ''Oklahoma'' sailed to

''Oklahoma'' rejoined the Scouting Fleet for exercises in the Caribbean, then returned to the West Coast in June 1930, for fleet operations through spring 1936. That summer, she carried midshipmen on a European training cruise, visiting northern ports. The cruise was interrupted by the outbreak of civil war in Spain. ''Oklahoma'' sailed to Bilbao

)

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize = 275 px

, map_caption = Interactive map outlining Bilbao

, pushpin_map = Spain Basque Country#Spain#Europe

, pushpin_map_caption ...

, arriving on 24 July 1936, to rescue American citizens and other refugee

A refugee, conventionally speaking, is a displaced person who has crossed national borders and who cannot or is unwilling to return home due to well-founded fear of persecution.

s whom she carried to Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = "Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gibr ...

and French ports. She returned to Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the Nor ...

on 11 September, and to the West Coast on 24 October.

The Pacific Fleet operations of ''Oklahoma'' during the next four years included joint operations with the Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

and the training of reservists. ''Oklahoma'' was based at Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the ...

from 29 December 1937, for patrols and exercises, and only twice returned to the mainland, once to have anti-aircraft guns and armor added to her superstructure at Puget Sound Navy Yard

Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, officially Puget Sound Naval Shipyard and Intermediate Maintenance Facility (PSNS & IMF), is a United States Navy shipyard covering 179 acres (0.7 km2) on Puget Sound at Bremerton, Washington in uninterrupted u ...

in early February 1941, and once to have armor replaced at San Pedro in mid-August of the same year. En route on 22 August, a severe storm hit ''Oklahoma''. One man was swept overboard and three others were injured. The next morning, a broken starboard propeller shaft forced the ship to halt, assess the damage, and sail to San Francisco, the closest navy yard with an adequate drydock. She remained in drydock, undergoing repairs until mid-October. The ship then returned to Hawaii.

The Washington Naval Treaty

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, was a treaty signed during 1922 among the major Allies of World War I, which agreed to prevent an arms race by limiting naval construction. It was negotiated at the Washington Nav ...

had precluded the Navy from replacing ''Oklahoma'', leading to the series of refits to extend her lifespan. The ship was planned to be retired on 2 May 1942.

Attack on Pearl Harbor

On 7 December 1941, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, ''Oklahoma'' was moored in berth Fox 5, on

On 7 December 1941, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, ''Oklahoma'' was moored in berth Fox 5, on Battleship Row

Battleship Row was the grouping of eight U.S. battleships in port at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, when the Japanese attacked on 7 December 1941. These ships bore the brunt of the Japanese assault. They were moored next to Ford Island when the attack co ...

, in the outboard position alongside the battleship . She was immediately targeted by planes from the Japanese aircraft carriers ''Akagi'' and ''Kaga'', and was struck by three torpedoes. The first and second hit seconds apart, striking amidships at approximately 07:50 or 07:53, below the waterline between the smokestack and mainmast. The torpedoes blew away a large section of her anti-torpedo bulge

The anti-torpedo bulge (also known as an anti-torpedo blister) is a form of defence against naval torpedoes occasionally employed in warship construction in the period between the First and Second World Wars. It involved fitting (or retrofittin ...

and spilled oil from the adjacent fuel bunkers' sounding tubes, but neither penetrated the hull. About 80 men scrambled to man the AA guns on deck, but were unable to use them because the firing locks were in the armory. Most of the men manned battle stations below the ship's waterline

The waterline is the line where the hull of a ship meets the surface of the water. Specifically, it is also the name of a special marking, also known as an international load line, Plimsoll line and water line (positioned amidships), that indi ...

or sought shelter in the third deck, protocol during an aerial attack. The third torpedo struck at 08:00, near Frame 65, hitting close to where the first two did, penetrating the hull, destroying the adjacent fuel bunkers on the second platform deck and rupturing access trunks to the two forward boiler rooms as well as the transverse bulkhead to the aft boiler room and the longitudinal bulkhead of the two forward firing rooms.

As she began to capsize

Capsizing or keeling over occurs when a boat or ship is rolled on its side or further by wave action, instability or wind force beyond the angle of positive static stability or it is upside down in the water. The act of recovering a vessel fro ...

to port, two more torpedoes struck, and her men were strafed

Strafing is the military practice of attacking ground targets from low-flying aircraft using aircraft-mounted automatic weapons.

Less commonly, the term is used by extension to describe high-speed firing runs by any land or naval craft such ...

as they abandoned ship. In less than twelve minutes, she rolled over until halted by her masts touching bottom, her starboard side above water, and a part of her keel exposed. It's believed the ship absorbed as many as eight hits in all. Many of her crew, however, remained in the fight, clambering aboard ''Maryland'' to help serve her anti-aircraft batteries

Battery most often refers to:

* Electric battery, a device that provides electrical power

* Battery (crime), a crime involving unlawful physical contact

Battery may also refer to:

Energy source

*Automotive battery, a device to provide power t ...

. Four hundred twenty-nine of her officers and enlisted men were killed or missing. One of those killed, Father Aloysius Schmitt, was the first American chaplain

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secular institution (such as a hospital, prison, military unit, intelligence ...

of any faith to die in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. Thirty-two others were wounded, and many were trapped within the capsized hull. Efforts to rescue them began within minutes of the ship's capsizing and continued into the night, in several cases rescuing men trapped inside the ship for hours. Julio DeCastro, a Hawaiian civilian yard worker, organized a team that saved 32 ''Oklahoma'' sailors. This was a particularly tricky operation as cutting open the hull released trapped air, raising the water levels around entombed men, while cutting in the wrong places could ignite stored fuel. It is likely that some survivors were never reached in time.

Some of those who died later had ships named after them, including Ensign

An ensign is the national flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality. The ensign is the largest flag, generally flown at the stern (rear) of the ship while in port. The naval ensign (also known as war ensign), used on warships, may be diffe ...

John C. England for whom and are named. was named for Ensign Charles M. Stern, Jr. was named for Chief Carpenter John Arnold Austin, who was also posthumously awarded the Navy Cross

The Navy Cross is the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps' second-highest military decoration awarded for sailors and marines who distinguish themselves for extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force. The medal is eq ...

for his actions during the attack. was named for Father Aloysius Schmitt. was named for Malcolm, Randolph, and Leroy Barber. In addition to Austin's Navy Cross, the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of val ...

was awarded to Ensign Francis C. Flaherty and Seaman James R. Ward, while three Navy and Marine Corps Medal

The Navy and Marine Corps Medal is the highest non-combat decoration awarded for heroism by the United States Department of the Navy to members of the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps. The medal was established by an act of Co ...

s were awarded to others on ''Oklahoma'' during the attack.

Salvage

By early 1942, it was determined that ''Oklahoma'' could be salvaged and that she was a navigational hazard, having rolled into the harbor's navigational channel. Even though it was cost-prohibitive to do so, the job of salvaging ''Oklahoma'' commenced on 15 July 1942, under the immediate command of Captain F. H. Whitaker, and a team from thePearl Harbor Naval Shipyard

The Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard and Intermediate Maintenance Facility is a United States Navy shipyard located in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. It is one of just four public shipyards operated by the United States Navy. The shipyard is physically a part ...

.

Preparations for righting the overturned hull took under eight months to complete. Air was pumped into interior chambers and improvised airlocks built into the ship, forcing of water out of the ship through the torpedo holes. of coral soil were deposited in front of her bow to prevent sliding and two barges were posted on either end of the ship to control the ship's rising.

Twenty-one derrick

A derrick is a lifting device composed at minimum of one guyed mast, as in a gin pole, which may be articulated over a load by adjusting its guys. Most derricks have at least two components, either a guyed mast or self-supporting tower, and ...

s were attached to the upturned hull; each carried high-tensile steel cables that were connected to hydraulic winching machines ashore. The righting (parbuckling

Parbuckle salvage, or ''parbuckling'', is the righting of a sunken vessel using rotational leverage. A common operation with smaller watercraft, parbuckling is also employed to right large vessels. In 1943, the was rotated nearly 180 degrees to ...

) operation began on 8 March, and was completed by 16 June 1943. Teams of naval specialists then entered the previously submerged ship to remove human remains. Cofferdam

A cofferdam is an enclosure built within a body of water to allow the enclosed area to be pumped out. This pumping creates a dry working environment so that the work can be carried out safely. Cofferdams are commonly used for construction or re ...

s were then placed around the hull to allow basic repairs to be undertaken so that the ship could be refloated; this work was completed by November. On 28 December, ''Oklahoma'' was towed into drydock No. 2, at the Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard. Once in the dock, her main guns, machinery, remaining ammunition, and stores were removed. The severest structural damage on the hull was also repaired to make the ship watertight. US Navy deemed her too old and too heavily damaged to be returned to service.

''Oklahoma'' was decommissioned on 1 September 1944, and all remaining armaments and superstructure were then removed. She was then put up for auction at the

''Oklahoma'' was decommissioned on 1 September 1944, and all remaining armaments and superstructure were then removed. She was then put up for auction at the Brooklyn Navy Yard

The Brooklyn Navy Yard (originally known as the New York Navy Yard) is a shipyard and industrial complex located in northwest Brooklyn in New York City, New York. The Navy Yard is located on the East River in Wallabout Bay, a semicircular bend ...

on 26 November 1946, with her engines, boilers, turbo generators, steering units and about of structural steel deemed salvageable. She was sold to Moore Drydock Co. of Oakland, California for $46,127.

Final voyage

In May 1947, a two-tug towing operation began to move the hull of ''Oklahoma'' from Pearl Harbor toSan Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay is a large tidal estuary in the U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the big cities of San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland.

San Francisco Bay drains water f ...

. Due to arrive on Memorial Day, a delegation of nearly 500 Oklahomans led by Governor Roy J. Turner

Roy Joseph Turner (November 6, 1894 – June 11, 1973) was an American businessman and Governor of the U.S. state of Oklahoma. Born in 1894, in Oklahoma Territory, he served in World War I, became a prominent businessman and eventually serv ...

planned to visit and pay final respects to the ship.

Disaster struck on 17 May, when the ships entered a storm more than from Hawaii. The tug ''Hercules'' put her searchlight on the former battleship, revealing that she had begun listing heavily. After radioing the naval base at Pearl Harbor, both tugs were instructed to turn around and head back to port. Without warning, ''Hercules'' was pulled back past ''Monarch'', which was being dragged backwards at . ''Oklahoma'' had begun to sink straight down, causing water to swamp the sterns of both tugs.

Both tug skippers had fortunately loosened their cable drums connecting the tow lines to ''Oklahoma''. As the battleship sank rapidly, the line from ''Monarch'' quickly played out, releasing the tug. However, ''Hercules'' cables did not release until the last possible moment, leaving her tossing and pitching above the grave of the sunken ''Oklahoma''. The battleship's exact location is unknown.

Memorials and recovery of remains

During dredging operations in 2006, the US Navy recovered a part of ''Oklahoma'' from the bottom of Pearl Harbor. The Navy believes it to be a portion of the port side rear fire control tower support mast. It was flown to

During dredging operations in 2006, the US Navy recovered a part of ''Oklahoma'' from the bottom of Pearl Harbor. The Navy believes it to be a portion of the port side rear fire control tower support mast. It was flown to Tinker Air Force Base

Tinker Air Force Base is a major United States Air Force base, with tenant U.S. Navy and other Department of Defense missions, located in Oklahoma County, Oklahoma, surrounded by Del City, Oklahoma City, and Midwest City.

The base, origina ...

then delivered to the Muskogee War Memorial Park in Muskogee, in 2010, where the , , barnacle-encrusted mast section is now on permanent outdoor display. The ship's bell and two of her screws are at the Kirkpatrick Science Museum in Oklahoma City. ''Oklahoma''s aft wheel is at the Oklahoma History Center in Oklahoma City.

On 7 December 2007, the 66th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor, a memorial for the 429 crew members who were killed in the attack was dedicated on Ford Island, just outside the entrance to where the battleship is docked as a museum. ''Missouri'' is moored where ''Oklahoma'' was moored when she was sunk. The USS ''Oklahoma'' memorial is part of Pearl Harbor National Memorial

Pearl Harbor National Memorial is a unit of the National Park System of the United States on the island of Oahu, Hawaii. The John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act removed the site from the World War II Valor in the Pac ...

and is an arrangement of engraved black granite walls and white marble posts. Only 35 of the 429 sailors and Marines

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refl ...

who died on ''Oklahoma'' were identified in the years following the attack. The remains of 394 unidentified sailors and Marines were first interred as unknowns in the Nu'uanu and Halawa cemeteries, but were all disinterred in 1947, in an unsuccessful attempt to identify more personnel. In 1950, all unidentified remains from ''Oklahoma'' were buried in 61 caskets in 45 graves at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific

The National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific (informally known as Punchbowl Cemetery) is a national cemetery located at Punchbowl Crater in Honolulu, Hawaii. It serves as a memorial to honor those men and women who served in the United St ...

.

Identification program

In April 2015, the Department of Defense announced, as part of a policy change that established threshold criteria for disinterment of unknowns, that the unidentified remains of the crew members of ''Oklahoma'' would be exhumed for DNA analysis, with the goal of returning identified remains to their families. The process began in June 2015, when four graves, two individual and two group graves, were disinterred for DNA analysis by theDefense POW/MIA Accounting Agency

The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) is an agency within the U.S. Department of Defense whose mission is to recover American military personnel listed as prisoners of war (POW) or missing in action (MIA) from designated past conflicts, ...

(DPAA). By December 2017, the identity of 100 crew members had been discovered, and with the numbers of sailor and Marine identities increasing at a steady pace, the 200th unknown was identified by 26 February 2019. Throughout 2019 and 2020, the DPAA continued to successfully identify more crew members, and on 4 February 2021, they announced the identity of the 300th unknown, a 19 year old Marine from Illinois.

As of 29 June 2021, the DPAA announced that the program was coming to a close, and that the remains of 51 crew members that could not be identified have been returned to Hawaii, and will be reinterred at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific at Punchbowl Crater

Punchbowl Crater is an extinct volcanic tuff cone located in Honolulu, Hawaii. It is the location of the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific.

The crater was formed some 75,000 to 100,000 years ago during the secondary activity of the H ...

, with a ceremony scheduled for 7 December, the 80th anniversary of the Attack on Pearl Harbor.

The program identified 343 crew members, including two Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of val ...

recipients, giving the DPAA a success rate of 88%. DPAA Director Kelly McKeague stated she had hoped to be able to identify at least a few more crew members before the program shut down, and in time for the ceremony. On 17 September 2021, the Department of Defense announced that number of identified was 346. After a final push to identify as many of the remaining unknown crew members as possible, the Department of Defense Department of Defence or Department of Defense may refer to:

Current departments of defence

* Department of Defence (Australia)

* Department of National Defence (Canada)

* Department of Defence (Ireland)

* Department of National Defense (Philipp ...

announced that they had identified a total 396 crew members. As was previously planned, the crew remains that could not be identified, numbering only 33, would be reinterred at the Punchbowl Cemetery, during a ceremony on 7 December, that will coincide with the anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor, 80 years earlier.

See also

*List of commanding officers of USS Oklahoma (BB-37)

USS ''Oklahoma'' was a battleship that served in the United States Navy from 2 May 1916, to 1 September 1944. The ship capsized and sank during the attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, but she was righted in 1943. While other ships su ...

* List of U.S. Navy losses in World War II

* Pearl Harbor Survivors Association

Notes

References

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *Other reading

* * * * * *External links

Maritimequest USS ''Oklahoma'' BB-37 Photo Gallery

2003: Survivors dedicate Pearl Harbor USS ''Oklahoma'' Memorial highway

*

USS ''Oklahoma'' (BB-37) Official Web Site

{{DEFAULTSORT:Oklahoma (BB-37) Nevada-class battleships Ships built by New York Shipbuilding Corporation 1914 ships Maritime incidents in 1915 Ship fires World War I battleships of the United States World War II battleships of the United States Ships present during the attack on Pearl Harbor Ships sunk during the attack on Pearl Harbor Shipwrecks of Hawaii Battleships sunk by aircraft Monuments and memorials in Hawaii Maritime incidents in 1947 World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument Maritime incidents in December 1941