UNESCO World Heritage Sites on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

(UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, scientific or other form of significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human Society, societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, and habits of the ...

and natural

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are p ...

heritage around the world considered to be of outstanding value to humanity".

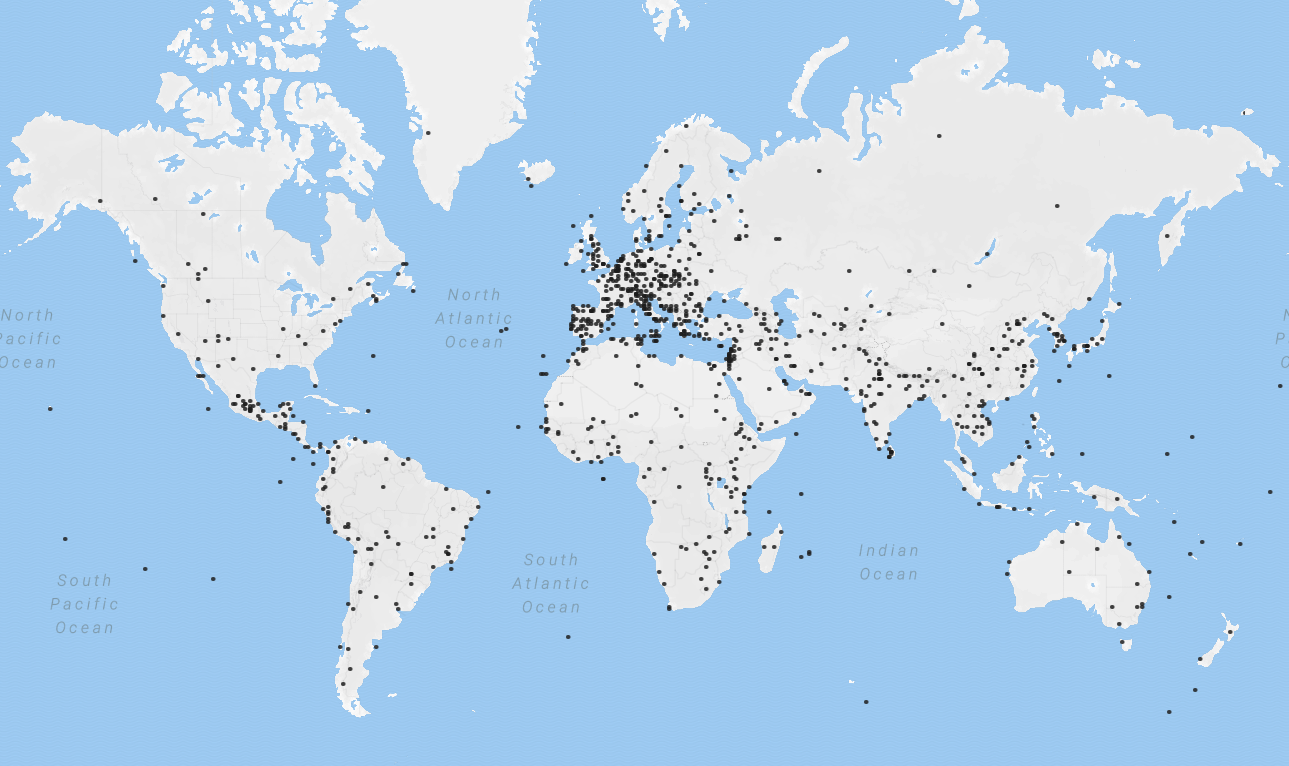

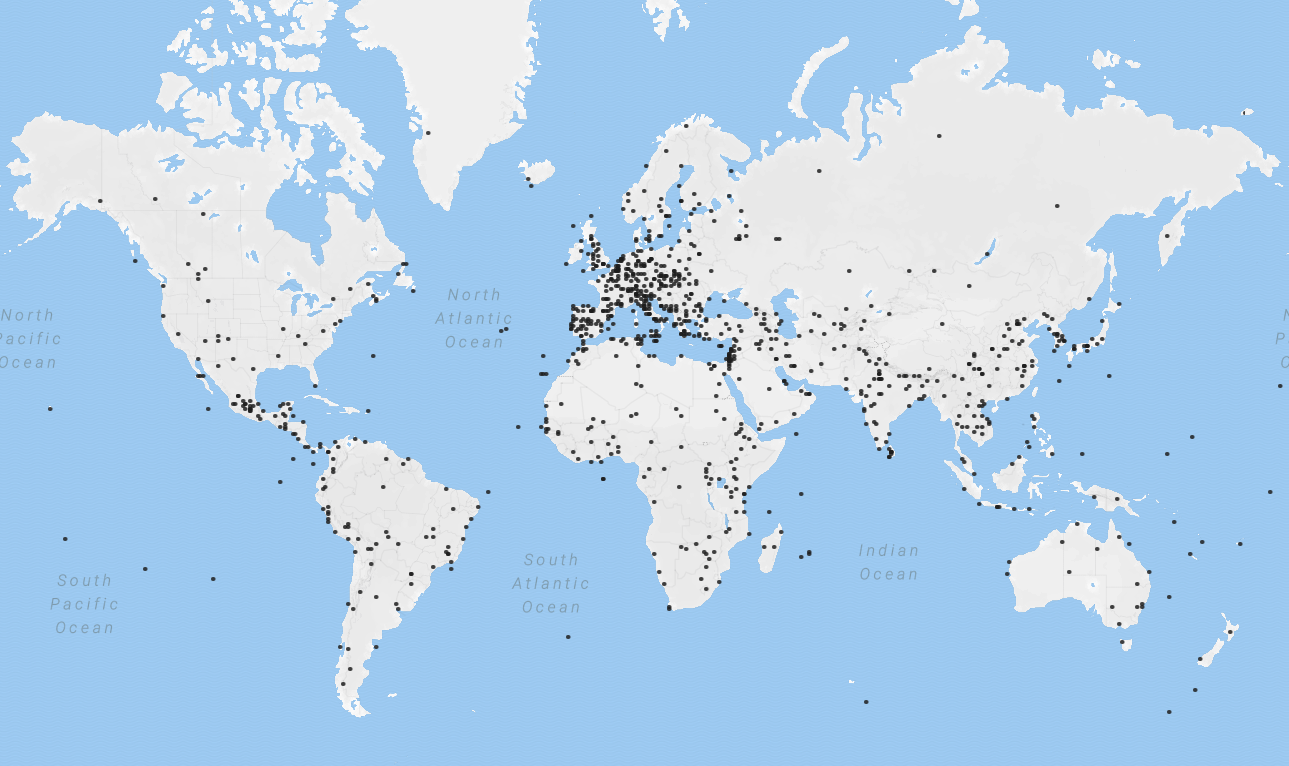

To be selected, a World Heritage Site must be a somehow unique landmark which is geographically and historically identifiable and has special cultural or physical significance. For example, World Heritage Sites might be ancient ruins or historical structures, buildings, cities, deserts, forests, islands, lakes, monuments, mountains, or wilderness areas. A World Heritage Site may signify a remarkable accomplishment of humanity, and serve as evidence of our intellectual history on the planet, or it might be a place of great natural beauty. As of August 2022, a total of 1,154 World Heritage Sites (897 cultural, 218 natural, and 39 mixed properties) exist across 167 countries. With 58 selected areas, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

is the country with the most sites on the list.

The sites are intended for practical conservation for posterity, which otherwise would be subject to risk from human or animal trespassing, unmonitored, uncontrolled or unrestricted access, or threat from local administrative negligence. Sites are demarcated by UNESCO as protected zones. The World Heritage Sites list is maintained by the international World Heritage Program administered by the UNESCO World Heritage Committee

The World Heritage Committee selects the sites to be listed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, including the World Heritage List and the List of World Heritage in Danger, defines the use of the World Heritage Fund and allocates financial assistance ...

, composed of 21 "states parties" that are elected by their General Assembly. The programme catalogues, names, and conserves sites of outstanding cultural or natural importance to the common culture and heritage of humanity. The programme began with the " Convention Concerning the Protection of the World's Cultural and Natural Heritage", which was adopted by the General Conference of UNESCO on 16 November 1972. Since then, 194 states have ratified the convention, making it one of the most widely recognised international agreements and the world's most popular cultural programme.

History

Origin

In 1954, the government ofEgypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

decided to build the new Aswan High Dam

The Aswan Dam, or more specifically since the 1960s, the Aswan High Dam, is one of the world's largest embankment dams, which was built across the Nile in Aswan, Egypt, between 1960 and 1970. Its significance largely eclipsed the previous Aswan Lo ...

, whose resulting future reservoir it would eventually inundate

A flood is an overflow of water ( or rarely other fluids) that submerges land that is usually dry. In the sense of "flowing water", the word may also be applied to the inflow of the tide. Floods are an area of study of the discipline hydrolog ...

a large stretch of the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

valley containing cultural treasures of ancient Egypt and ancient Nubia

Nubia () (Nobiin: Nobīn, ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the first cataract of the Nile (just south of Aswan in southern Egypt) and the confluence of the Blue and White Niles (in Khartoum in central Sudan), or ...

. In 1959, the governments of Egypt and Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

requested UNESCO to assist them to protect and rescue the endangered monuments and sites. In 1960, the Director-General of UNESCO launched the International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia. This International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia

The International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia was the relocation of 22 monuments in Lower Nubia, in Southern Egypt and northern Sudan, between 1960 and 1980. The success of the project, in particular the creation of a coalition of 50 ...

resulted in the excavation and recording of hundreds of sites, the recovery of thousands of objects, as well as the salvage and relocation to higher ground of several important temples. The most famous of these are the temple complexes of Abu Simbel

Abu Simbel is a historic site comprising two massive rock-cut temples in the village of Abu Simbel ( ar, أبو سمبل), Aswan Governorate, Upper Egypt, near the border with Sudan. It is situated on the western bank of Lake Nasser, about sou ...

and Philae

; ar, فيلة; cop, ⲡⲓⲗⲁⲕ

, alternate_name =

, image = File:File, Asuán, Egipto, 2022-04-01, DD 93.jpg

, alt =

, caption = The temple of Isis from Philae at its current location on Agilkia Island in Lake Nasse ...

. The campaign ended in 1980 and was considered a success. To thank countries which especially contributed to the campaign's success, Egypt donated four temples; the Temple of Dendur

The Temple of Dendur (Dendoor in the 19th century) is a Roman Egyptian religious structure originally located in Tuzis (later Dendur), Nubia about south of modern Aswan. Around 23 BCE, Emperor Augustus commissioned the temple dedicated to the E ...

was moved to the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City, colloquially "the Met", is the largest art museum in the Americas. Its permanent collection contains over two million works, divided among 17 curatorial departments. The main building at 1000 ...

in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, the Temple of Debod

The Temple of Debod ( es, Templo de Debod) is an ancient Egyptian temple that was dismantled as part of the International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia and rebuilt in the center of Madrid, Spain, in Parque de la Montaña, Madrid, a squa ...

to the Parque del Oeste

The Parque del Oeste (in English: ''Western Park'') is a park of the city of Madrid (Spain) situated between the Autovía A-6, the Ciudad Universitaria de Madrid and the district of Moncloa. Before the 20th century, the land that the park cu ...

in Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

, the Temple of Taffeh

The Temple of Taffeh ( ar, معبد طافا) is an ancient Egyptian temple which was presented to the Netherlands for its help in contributing to the historical preservation of Egyptian antiquities in the 1960s during the International Campaign ...

to the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden

The (English: National Museum of Antiquities) is the national archaeological museum of the Netherlands, located in Leiden. It grew out of the collection of Leiden University and still closely co-operates with its Faculty of Archaeology. The ...

in Leiden

Leiden (; in English and archaic Dutch also Leyden) is a city and municipality in the province of South Holland, Netherlands. The municipality of Leiden has a population of 119,713, but the city forms one densely connected agglomeration wit ...

, and the Temple of Ellesyia

The Temple of Ellesyia is an ancient Egyptian rock-cut temple originally located near the site of Qasr Ibrim. It was built during the 18th Dynasty by the Pharaoh Thutmosis III. The temple was dedicated to the deities Amun, Horus and Satis.

...

to Museo Egizio

The Museo Egizio (Italian language, Italian for Egyptian Museum) is an archaeological museum in Turin, Piedmont, Italy, specializing in Art of Ancient Egypt, Egyptian archaeology and anthropology. It houses List of museums of Egyptian antiquitie ...

in Turin.

The project cost US$80 million (equivalent to $ million in ), about $40 million of which was collected from 50 countries. The project's success led to other safeguarding campaigns, such as saving Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

and its lagoon in Italy, the ruins of Mohenjo-daro

Mohenjo-daro (; sd, موئن جو دڙو'', ''meaning 'Mound of the Dead Men';Borobodur Temple Compounds in Indonesia. Together with the

The World Heritage Committee has divided the world into five geographic zones which it calls regions: Africa, Arab states, Asia and the Pacific, Europe and North America, and Latin America and the Caribbean. Russia and the

The World Heritage Committee has divided the world into five geographic zones which it calls regions: Africa, Arab states, Asia and the Pacific, Europe and North America, and Latin America and the Caribbean. Russia and the

ImageSize = width:600 height:auto barincrement:15

PlotArea = top:10 bottom:30 right:50 left:20

AlignBars = early

DateFormat = yyyy

Period = from:0 till:60

TimeAxis = orientation:horizontal

ScaleMajor = unit:year increment:10 start:0

Colors =

id:yellow value:yelloworange

Backgroundcolors = canvas:white

Define $n24 = 24

BarData =

barset:Studentenbuden

PlotData =

width:5 align:left fontsize:S shift:(5,-4) anchor:till

barset:Studentenbuden

from:0 till:58 color:purple text:"

UNESCO World Heritage portal

– Official website *

The World Heritage List

– Official searchable list of all Inscribed Properties *

KML file of the World Heritage List

– Official

UNESCO Information System on the State of Conservation of World Heritage properties

– Searchable online tool with over 3,400 reports on World Heritage Sites *

Official overview of the World Heritage Forest Program

*

Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage

– Official 1972 Convention Text in seven languages **

– Fully indexed and crosslinked with other documents

Top Breathtaking world heritage sites by UNESCO

Protected Planet

– View all Natural World Heritage Sites in the World Database on Protected Areas

World Heritage Site – Smithsonian Ocean Portal

UNESCO chair in ICT

to develop and promote

UNESCO World Heritage Sites

showcased in Google Arts & Culture {{Authority control 1972 in the environment 1972 introductions Global culture Protected areas UNESCO

International Council on Monuments and Sites

The International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS; french: links=no, Conseil international des monuments et des sites) is a professional association that works for the conservation and protection of cultural heritage places around the worl ...

, UNESCO then initiated a draft convention to protect cultural heritage.

Convention and background

The convention (the signed document ofinternational agreement

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal perso ...

) guiding the work of the World Heritage Committee

The World Heritage Committee selects the sites to be listed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, including the World Heritage List and the List of World Heritage in Danger, defines the use of the World Heritage Fund and allocates financial assistance ...

was developed over a seven-year period (1965–1972).

The United States initiated the idea of safeguarding places of high cultural or natural importance. A White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

conference in 1965 called for a "World Heritage Trust" to preserve "the world's superb natural and scenic areas and historic sites for the present and the future of the entire world citizenry". The International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; officially International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natu ...

developed similar proposals in 1968, which were presented in 1972 to the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment

The United Nations Conference on the Human Environment was held in Stockholm, Sweden, from June 5–16 in 1972.

When the United Nations General Assembly decided to convene the 1972 Stockholm Conference, taking up the offer of the Government of S ...

in Stockholm

Stockholm () is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in Sweden by population, largest city of Sweden as well as the List of urban areas in the Nordic countries, largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people liv ...

. Under the World Heritage Committee, signatory countries are required to produce and submit periodic data reporting Data reporting is the process of collecting and submitting data which gives rise to accurate analyses of the facts on the ground; inaccurate data reporting can lead to vastly uninformed decision-making based on erroneous evidence. Different from da ...

providing the committee with an overview of each participating nation's implementation of the World Heritage Convention and a 'snapshot' of current conditions at World Heritage properties.

Based on the draft convention that UNESCO had initiated, a single text was eventually agreed upon by all parties, and the "Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage" was adopted by the General Conference of UNESCO on 16 November 1972. The Convention came into force on 17 December 1975. As of March 2022, it has been ratified by 194 states: 190 UN member states

The United Nations member states are the sovereign states that are members of the United Nations (UN) and have equal representation in the United Nations General Assembly, UN General Assembly. The UN is the world's largest international o ...

, 2 UN observer states (the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of Rome ...

and the State of Palestine

Palestine ( ar, فلسطين, Filasṭīn), Legal status of the State of Palestine, officially the State of Palestine ( ar, دولة فلسطين, Dawlat Filasṭīn, label=none), is a state (polity), state located in Western Asia. Officiall ...

), and 2 states in free association with New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

(the Cook Islands

)

, image_map = Cook Islands on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, capital = Avarua

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Avarua

, official_languages =

, lan ...

and Niue

Niue (, ; niu, Niuē) is an island country in the South Pacific Ocean, northeast of New Zealand. Niue's land area is about and its population, predominantly Polynesian, was about 1,600 in 2016. Niue is located in a triangle between Tong ...

). Only three UN member states have not ratified the convention: Liechtenstein

Liechtenstein (), officially the Principality of Liechtenstein (german: link=no, Fürstentum Liechtenstein), is a German-speaking microstate located in the Alps between Austria and Switzerland. Liechtenstein is a semi-constitutional monarchy ...

, Nauru

Nauru ( or ; na, Naoero), officially the Republic of Nauru ( na, Repubrikin Naoero) and formerly known as Pleasant Island, is an island country and microstate in Oceania, in the Central Pacific. Its nearest neighbour is Banaba Island in Ki ...

, and Tuvalu

Tuvalu ( or ; formerly known as the Ellice Islands) is an island country and microstate in the Polynesian subregion of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. Its islands are situated about midway between Hawaii and Australia. They lie east-northeast ...

.

Objectives and positive results

By assigning places as World Heritage Sites, UNESCO wants to help to pass them on to future generations. Its motivation is that " ritage is our legacy from the past, what we live with today" and that both cultural and natural heritage are "irreplaceable sources of life and inspiration". UNESCO's mission with respect to World Heritage consists of eight sub targets. These include encouraging the commitment of countries and local population to World Heritage conservation in various ways, providing emergency assistance for sites in danger, offering technical assistance and professional training, and supporting States Parties' public awareness-building activities. Being listed as a World Heritage Site can positively affect the site, its environment, and interactions between them. A listed site gains international recognition and legal protection, and can obtain funds from among others the World Heritage Fund to facilitate its conservation under certain conditions. UNESCO reckons the restorations of the following four sites among its success stories:Angkor

Angkor ( km, អង្គរ , 'Capital city'), also known as Yasodharapura ( km, យសោធរបុរៈ; sa, यशोधरपुर),Headly, Robert K.; Chhor, Kylin; Lim, Lam Kheng; Kheang, Lim Hak; Chun, Chen. 1977. ''Cambodian-Engl ...

in Cambodia, the Old City of Dubrovnik

Dubrovnik (), historically known as Ragusa (; see notes on naming), is a city on the Adriatic Sea in the region of Dalmatia, in the southeastern semi-exclave of Croatia. It is one of the most prominent tourist destinations in the Mediterran ...

in Croatia, the Wieliczka Salt Mine

The Wieliczka Salt Mine ( pl, Kopalnia soli Wieliczka) is a salt mine in the town of Wieliczka, near Kraków in southern Poland.

From Neolithic times, sodium chloride (table salt) was produced there from the upwelling brine. The Wieliczka sa ...

near Kraków in Poland, and the Ngorongoro Conservation Area

The Ngorongoro Conservation Area (, ) is a protected area and a UNESCO World Heritage Site located in Ngorongoro District, west of Arusha City in Arusha Region, within the Crater Highlands geological area of northern Tanzania. The area is nam ...

in Tanzania. Additionally, the local population around a site may benefit from significantly increased tourism revenue. When there are significant interactions between people and the natural environment, these can be recognised as "cultural landscapes".

Nomination process

A country must first identify its significant cultural and natural sites in a document known as the Tentative List. Next, it can place sites selected from that list into a Nomination File, which is evaluated by theInternational Council on Monuments and Sites

The International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS; french: links=no, Conseil international des monuments et des sites) is a professional association that works for the conservation and protection of cultural heritage places around the worl ...

and the World Conservation Union

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; officially International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natu ...

. A country may not nominate sites that have not been first included on its Tentative List. The two international bodies make recommendations to the World Heritage Committee for new designations. The Committee meets once a year to determine what nominated properties to add to the World Heritage List; sometimes it defers its decision or requests more information from the country that nominated the site. There are ten selection criteria – a site must meet at least one to be included on the list.

Selection criteria

Until 2004, there were six sets of criteria for cultural heritage and four for natural heritage. In 2005, UNESCO modified these and now has one set of ten criteria. Nominated sites must be of "outstanding universal value" and must meet at least one of the ten criteria.Cultural

- "To represent a masterpiece of human creative genius"

- "To exhibit an important interchange of human values, over a span of time or within a cultural area of the world, on developments in architecture or technology, monumental arts, town-planning or landscape design"

- "To bear a unique or at least exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition or to a civilization which is living, or which has disappeared"

- "To be an outstanding example of a type of building, architectural or technological ensemble or landscape which illustrates (a) significant stage(s) in human history"

- "To be an outstanding example of a traditional human settlement, land-use, or sea-use which is representative of a culture (or cultures), or human interaction with the environment especially when it has become vulnerable under the impact of irreversible change"

- "To be directly or tangibly associated with events or living traditions, with ideas, or with beliefs, with artistic and literary works of outstanding universal significance"

Natural

- "To contain superlative natural phenomena or areas of exceptional natural beauty and aesthetic importance"

- "To be outstanding examples representing major stages of earth's history, including the record of life, significant on-going geological processes in the development of landforms, or significant geomorphic or physiographic features"

- "To be outstanding examples representing significant on-going ecological and biological processes in the evolution and development of terrestrial, fresh water, coastal and marine ecosystems and communities of plants and animals"

- "To contain the most important and significant natural habitats for in-situ conservation of biological diversity, including those containing threatened species of outstanding universal value from the point of view of science or conservation"

Extensions and other modifications

A country may request to extend or reduce the boundaries, modify the official name, or change the selection criteria of one of its already listed sites. Any proposal for a significant boundary change or to modify the site's selection criteria must be submitted as if it were a new nomination, including first placing it on the Tentative List and then onto the Nomination File. A request for a minor boundary change, one that does not have a significant impact on the extent of the property or affect its "outstanding universal value", is also evaluated by the advisory bodies before being sent to the committee. Such proposals can be rejected by either the advisory bodies or the Committee if they judge it to be a significant change instead of a minor one. Proposals to change a site's official name are sent directly to the committee.Endangerment

A site may be added to theList of World Heritage in Danger

The List of World Heritage in Danger is compiled by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) through the World Heritage Committee according to Article 11.4 of the World Heritage Convention,Full title: ''Conv ...

if conditions threaten the characteristics for which the landmark or area was inscribed on the World Heritage List. Such problems may involve armed conflict and war, natural disasters, pollution, poaching, or uncontrolled urbanisation or human development. This danger list is intended to increase international awareness of the threats and to encourage counteractive measures. Threats to a site can be either proven imminent threats or potential dangers that could have adverse effects on a site.

The state of conservation for each site on the danger list is reviewed yearly; after this, the Committee may request additional measures, delete the property from the list if the threats have ceased or consider deletion from both the List of World Heritage in Danger and the World Heritage List. Only three sites have ever been delisted

In corporate finance, a listing refers to the company's shares being on the list (or board) of stock that are officially traded on a stock exchange. Some stock exchanges allow shares of a foreign company to be listed and may allow dual listing, su ...

: the Arabian Oryx Sanctuary

The Wildlife Reserve in Al Wusta (formerly the Arabian Oryx Sanctuary) is an animal sanctuary in the Omani Central Desert and Coastal Hills. Formerly included in the UNESCO ''World Heritage'' list, in 2007 it became the first site to be removed f ...

in Oman, the Dresden Elbe Valley

The Dresden Elbe Valley is a cultural landscape and former World Heritage Site stretching along the Elbe river in Dresden, the state capital of Saxony, Germany. The valley, extending for some and passing through the Dresden Basin, is one of two m ...

in Germany, and the Liverpool Maritime Mercantile City

Liverpool Maritime Mercantile City is a former UNESCO designated World Heritage Site in Liverpool, England, that comprised six locations in the city centre including the Pier Head, Albert Dock and William Brown Street, and many of the city's mos ...

in the United Kingdom. The Arabian Oryx Sanctuary was directly delisted in 2007, instead of first being put on the danger list, after the Omani government decided to reduce the protected area's size by 90 per cent. The Dresden Elbe Valley was first placed on the danger list in 2006 when the World Heritage Committee decided that plans to construct the Waldschlösschen Bridge

The Waldschlösschen Bridge (german: Waldschlößchenbrücke or Waldschlösschenbrücke, links=no) is a road bridge across the Elbe river in Dresden. The bridge was intended to remedy inner-city traffic congestion. Its construction was highly con ...

would significantly alter the valley's landscape. In response, Dresden City Council attempted to stop the bridge's construction. However, after several court decisions allowed the building of the bridge to proceed, the valley was removed from the World Heritage List in 2009. Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

's World Heritage status was revoked in July 2021, following developments (Liverpool Waters

Liverpool Waters is a large scale £5.5bn development that has been proposed by the Peel Group in the Vauxhall, Liverpool, Vauxhall area of Liverpool, Merseyside, England. The development will make use of a series of presently derelict dock sp ...

and Bramley-Moore Dock Stadium

Everton Stadium at Bramley-Moore Dock is an under construction football stadium that will become the home ground for Everton F.C. Located on Bramley-Moore Dock in Vauxhall, Liverpool, England, it is due to open for the start of the 2024–25 se ...

) on the northern docks of the World Heritage site leading to the "irreversible loss of attributes" on the site.

The first global assessment to quantitatively measure threats to Natural World Heritage Sites found that 63 per cent of sites have been damaged by increasing human pressures including encroaching roads, agriculture infrastructure and settlements over the last two decades. These activities endanger Natural World Heritage Sites and could compromise their unique values. Of the Natural World Heritage Sites that contain forest, 91 per cent experienced some loss since 2000. Many of them are more threatened than previously thought and require immediate conservation action.

Furthermore, the destruction of cultural assets and identity-establishing sites is one of the primary goals of modern asymmetrical warfare. Therefore, terrorists, rebels and mercenary armies deliberately smash archaeological sites, sacred and secular monuments and loot libraries, archives and museums. The UN, United Nations peacekeeping

Peacekeeping by the United Nations is a role held by the Department of Peace Operations as an "instrument developed by the organization as a way to help countries torn by conflict to create the conditions for lasting peace". It is distinguished ...

and UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

in cooperation with Blue Shield International

The Blue Shield, formerly the International Committee of the Blue Shield, is an international organization founded in 1996 to protect the world's cultural heritage from threats such as armed conflict and natural disasters. Originally intended as ...

are active in preventing such acts. "No strike lists" are also created to protect cultural assets from air strikes. However, only through cooperation with the locals can the protection of World Heritage Sites, archaeological finds, exhibits and archaeological sites from destruction, looting and robbery be implemented sustainably

Specific definitions of sustainability are difficult to agree on and have varied in the literature and over time. The concept of sustainability can be used to guide decisions at the global, national, and individual levels (e.g. sustainable livin ...

. The founding president of Blue Shield International Karl von Habsburg

Karl von Habsburg (given names: ''Karl Thomas Robert Maria Franziskus Georg Bahnam''; born 11 January 1961) is an Austrian politician and the head of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine, therefore being a claimant to the defunct Austro-Hungarian t ...

summed it up with the words: "Without the local community and without the local participants, that would be completely impossible".

Criticism

Despite the successes of World Heritage listing in promoting conservation, the UNESCO-administered project has attracted criticism. This was caused by perceived under-representation of heritage sites outside Europe, disputed decisions on site selection and adverse impact of mass tourism on sites unable to manage rapid growth in visitor numbers. A large lobbying industry has grown around the awards, because World Heritage listing can significantly increase tourism returns. Site listing bids are often lengthy and costly, putting poorer countries at a disadvantage. Eritrea's efforts to promoteAsmara

Asmara ( ), or Asmera, is the capital and most populous city of Eritrea, in the country's Central Region. It sits at an elevation of , making it the sixth highest capital in the world by altitude and the second highest capital in Africa. The ...

are one example. In 2016, the Australian government was reported to have successfully lobbied for the World Heritage Site Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef system composed of over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over over an area of approximately . The reef is located in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland, ...

conservation efforts to be removed from a UNESCO report titled "World Heritage and Tourism in a Changing Climate". The Australian government's actions, involving considerable expense for lobbying and visits for diplomats, were in response to their concern about the negative impact that an "at risk" label could have on tourism revenue at a previously designated UNESCO World Heritage Site. In 2021, international scientists recommended UNESCO to put the Great Barrier Reef on the endangered list, as global climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to E ...

had caused a further negative state of the corals and water quality. Again, the Australian government campaigned against this, and in July 2021, the World Heritage Committee

The World Heritage Committee selects the sites to be listed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, including the World Heritage List and the List of World Heritage in Danger, defines the use of the World Heritage Fund and allocates financial assistance ...

, made up diplomatic representatives of 21 countries, ignored UNESCO's assessment, based on studies of scientists, "that the reef was clearly in danger from climate change and so should be placed on the list." According to environmental protection groups, this "decision was a victory for cynical lobbying and that Australia, as custodians of the world’s biggest coral reef, was now on probation."

Several listed locations, such as Casco Viejo

or in Spanish or or in Basque are different names for the medieval neighbourhood of Bilbao, part of the Ibaiondo district. The names mean ''Seven Streets'' or ''Old Town'' respectively and it used to be the walled part of the town until th ...

in Panama and Hội An

Hội An (), formerly known as Fai-Fo or Faifoo, is a city with a population of approximately 120,000 in Vietnam's Quảng Nam Province and is noted as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1999. Along with the Cu Lao Cham archipelago, it is part o ...

in Vietnam, have struggled to strike a balance between the economic benefits of catering to greatly increased visitor numbers after the recognition and preserving the original culture and local communities.

Statistics

The World Heritage Committee has divided the world into five geographic zones which it calls regions: Africa, Arab states, Asia and the Pacific, Europe and North America, and Latin America and the Caribbean. Russia and the

The World Heritage Committee has divided the world into five geographic zones which it calls regions: Africa, Arab states, Asia and the Pacific, Europe and North America, and Latin America and the Caribbean. Russia and the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historically ...

states are classified as European, while Mexico and the Caribbean are classified as belonging to the Latin America and Caribbean zone. The UNESCO geographic zones also give greater emphasis on administrative, rather than geographic associations. Hence, Gough Island

upright=1.3, Map of Gough island

Gough Island ( ), also known historically as Gonçalo Álvares, is a rugged volcanic island in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a dependency of Tristan da Cunha and part of the British overseas territory of Sain ...

, located in the South Atlantic, is part of the Europe and North America region because the British government nominated the site.

The table below includes a breakdown of the sites according to these zones and their classification :

Countries with 15 or more sites

This overview lists the 23 countries with 15 or more World Heritage Sites:Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

" (58)

from:0 till:56 color:purple text:"China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

" (56)

from:0 till:51 color:purple text:"Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

" (51)

from:0 till:49 color:blue text:"France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

" (49)

from:0 till:49 color:blue text:"Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

" (49)

from:0 till:40 color:blue text:"India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

" (40)

from:0 till:35 color:green text:"Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

" (35)

from:0 till:33 color:green text:"United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

" (33)

from:0 till:30 color:green text:"Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

" (30)

from:0 till:26 color:yellow text:"Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

" (26)

from:0 till:25 color:yellow text:"Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

" (25)

from:0 till:24 color:yellow text:"United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

" ($n24)

from:0 till:23 color:yellow text:"Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

" (23)

from:0 till:20 color:yellow text:"Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

" (20)

from:0 till:20 color:yellow text:"Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

" (20)

from:0 till:19 color:orange text:"Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

" (19)

from:0 till:18 color:orange text:"Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

" (18)

from:0 till:17 color:orange text:"Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

" (17)

from:0 till:17 color:orange text:"Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

" (17)

from:0 till:16 color:orange text:"Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast. The ...

" (16)

from:0 till:15 color:orange text:"Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

" (15)

from:0 till:15 color:orange text:"South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and sharing a Korean Demilitarized Zone, land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed ...

" (15)

from:0 till:15 color:orange text:"Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

" (15)

barset:skip

See also

*GoUNESCO

GoUNESCO is an umbrella of initiatives that help promote awareness and provide tools for laypersons to engage with heritage. GoUNESCO was created by Ajay Reddy in 2012. It is supported by UNESCO, New Delhi.

History

GoUNESCO began when Ajay Red ...

– initiative to promote awareness and provide tools for laypersons to engage with heritage

* Index of conservation articles

This is an index of conservation topics. It is an alphabetical index of articles relating to conservation biology and conservation of the natural environment.

A

* Abiotic stress - Adaptive management - Adventive plant - Aerial-seeding - Agreed M ...

* Lists of World Heritage Sites

This is a list of the lists of World Heritage Sites. A World Heritage Site is a place that is listed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as having special cultural or physical significance.

General lis ...

* Former UNESCO World Heritage Sites

The designation of World Heritage Site is prestigious. It bestows honour and economic benefit, by encouraging tourism.

World Heritage Sites may lose their designation when the UNESCO World Heritage Committee determines that they are not properl ...

* Memory of the World Programme

Memory is the faculty of the mind by which data or information is encoded, stored, and retrieved when needed. It is the retention of information over time for the purpose of influencing future action. If past events could not be remembered, ...

* UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists

UNESCO established its Lists of Intangible Cultural Heritage with the aim of ensuring better protection of important intangible cultural heritages worldwide and the awareness of their significance.Compare: This list is published by the Intergover ...

* Ramsar Convention

The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat is an international treaty for the conservation and sustainable use of Ramsar sites (wetlands). It is also known as the Convention on Wetlands. It i ...

– international agreement on wetlands recognition

Footnotes

References

Bibliography

* *External links

UNESCO World Heritage portal

– Official website *

The World Heritage List

– Official searchable list of all Inscribed Properties *

KML file of the World Heritage List

– Official

KML

Keyhole Markup Language (KML) is an XML notation for expressing geographic annotation and visualization within two-dimensional maps and three-dimensional Earth browsers. KML was developed for use with Google Earth, which was originally named Key ...

version of the list for Google Earth

Google Earth is a computer program that renders a 3D computer graphics, 3D representation of Earth based primarily on satellite imagery. The program maps the Earth by superimposition, superimposing satellite images, aerial photography, and geog ...

and NASA Worldwind

NASA WorldWind is an open-source (released under the NOSA license and the Apache 2.0 license) virtual globe. According to the website (https://worldwind.arc.nasa.gov/), "WorldWind is an open source virtual globe API. WorldWind allow ...

*UNESCO Information System on the State of Conservation of World Heritage properties

– Searchable online tool with over 3,400 reports on World Heritage Sites *

Official overview of the World Heritage Forest Program

*

Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage

– Official 1972 Convention Text in seven languages **

– Fully indexed and crosslinked with other documents

Top Breathtaking world heritage sites by UNESCO

Protected Planet

– View all Natural World Heritage Sites in the World Database on Protected Areas

World Heritage Site – Smithsonian Ocean Portal

UNESCO chair in ICT

to develop and promote

sustainable tourism

Sustainable tourism is a concept that covers the complete tourism experience, including concern for economic, social and environmental issues as well as attention to improving tourists' experiences and addressing the needs of host communities. Su ...

in World Heritage Sites

UNESCO World Heritage Sites

showcased in Google Arts & Culture {{Authority control 1972 in the environment 1972 introductions Global culture Protected areas UNESCO