U.S. presidential election, 1980 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 1980 United States presidential election was the 49th quadrennial

In August, after the Republican National Convention, Ronald Reagan gave a campaign speech at the annual Neshoba County Fair on the outskirts of

In August, after the Republican National Convention, Ronald Reagan gave a campaign speech at the annual Neshoba County Fair on the outskirts of  Two days later, Reagan appeared at the

Two days later, Reagan appeared at the

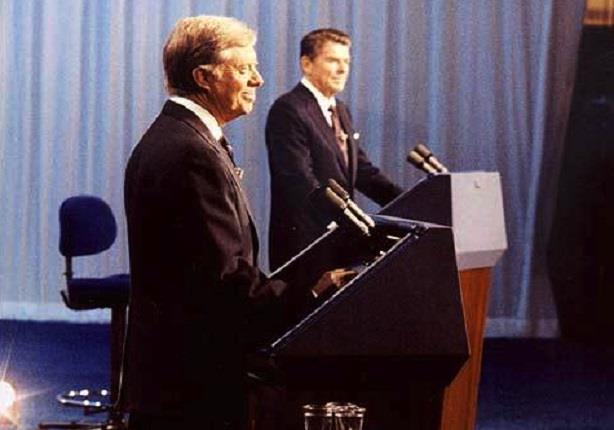

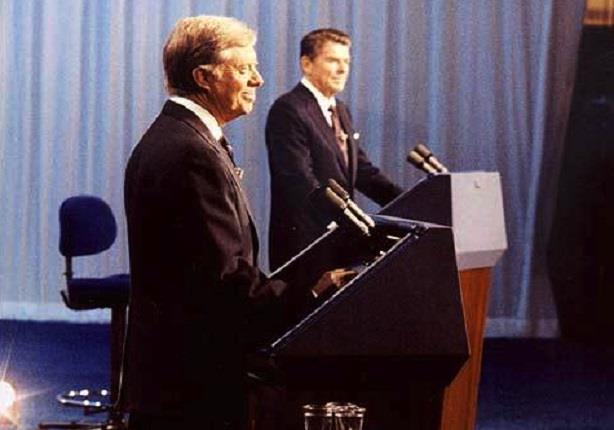

The presidential debate between President Carter and Governor Reagan was moderated by Howard K. Smith and presented by the League of Women Voters. The showdown ranked among the highest ratings of any

The presidential debate between President Carter and Governor Reagan was moderated by Howard K. Smith and presented by the League of Women Voters. The showdown ranked among the highest ratings of any

Online NewsHour: "Remembering Sen. Eugene McCarthy"

December 12, 2005.

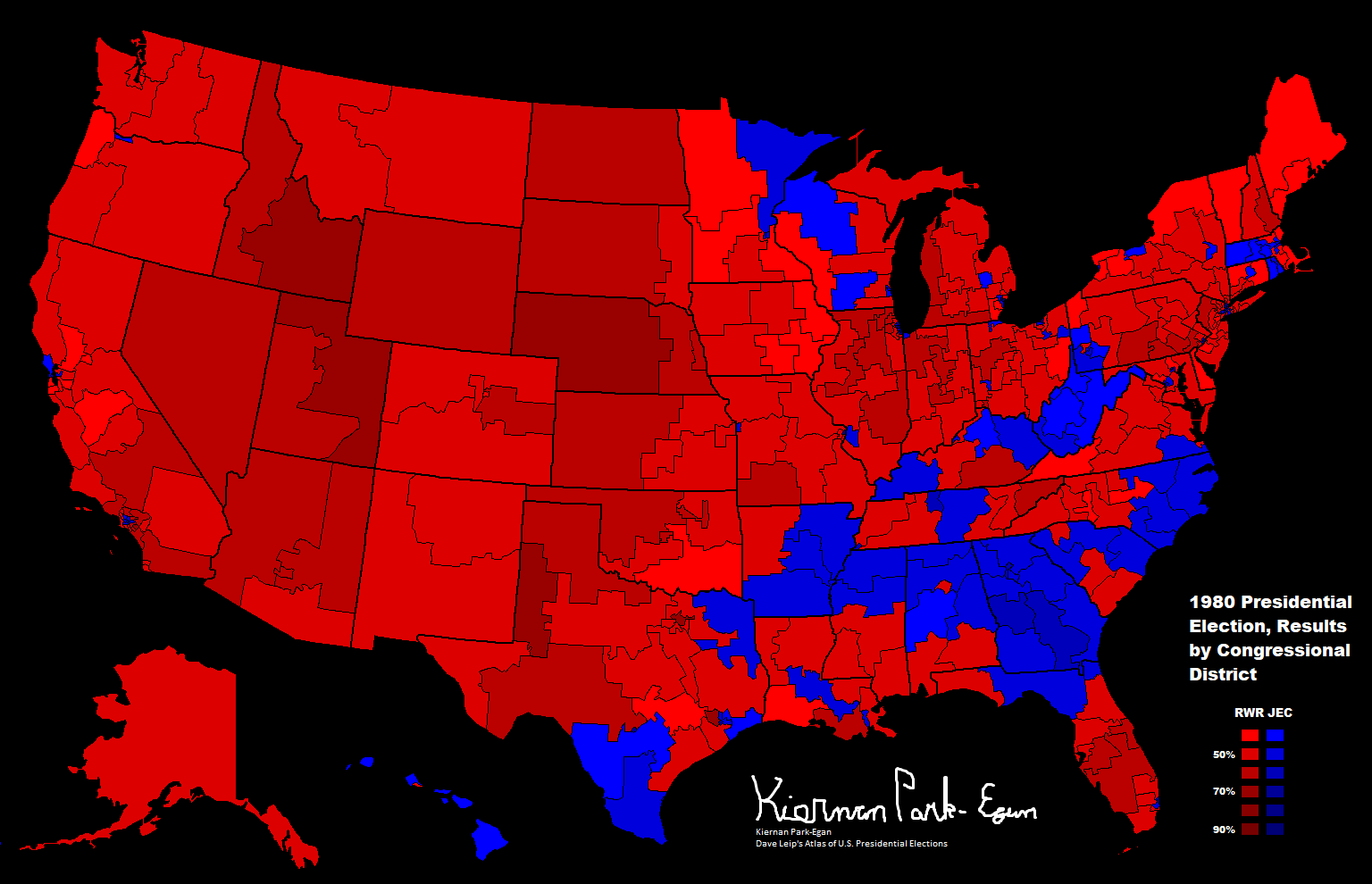

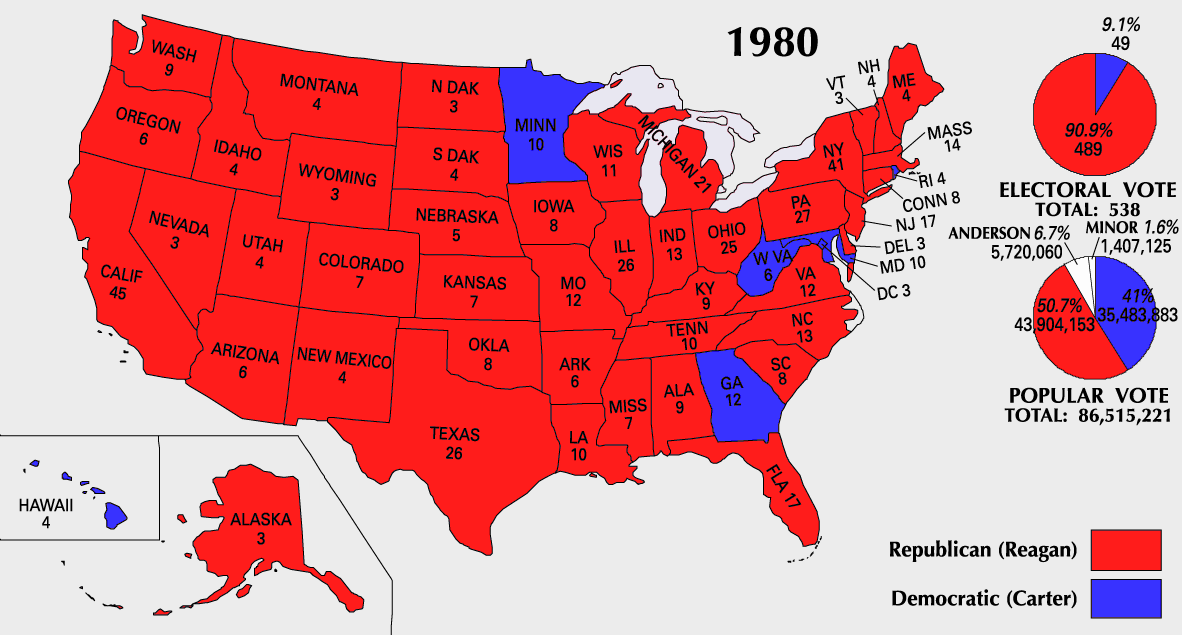

The election was held on November 4, 1980. Ronald Reagan and running mate George H. W. Bush beat Carter by almost 10 percentage points in the popular vote. Republicans also gained control of the Senate on

The election was held on November 4, 1980. Ronald Reagan and running mate George H. W. Bush beat Carter by almost 10 percentage points in the popular vote. Republicans also gained control of the Senate on

File:1980 United States presidential election results map by county.svg, Results by county, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote

online review by Michael Barone

* Davies, Gareth, and Julian E. Zelizer, eds. ''America at the Ballot Box: Elections and Political History'' (2015) pp. 196–218. * * * * Hogue, Andrew P. ''Stumping God: Reagan, Carter, and the Invention of a Political Faith'' (Baylor University Press; 2012) 343 pages; A study of religious rhetoric in the campaign * Mason, Jim (2011)

Lanham, MD: University Press of America. . * *

* Stanley, Timothy. ''Kennedy vs. Carter: The 1980 Battle for the Democratic Party's Soul'' (University Press of Kansas, 2010) 298 pages. A revisionist history of the 1970s and their political aftermath that argues that Ted Kennedy's 1980 campaign was more popular than has been acknowledged; describes his defeat by Jimmy Carter in terms of a "historical accident" rather than perceived radicalism. * * *

Campaign commercials from the 1980 election

* —Michael Sheppard, Massachusetts Institute of Technology *

Portrayal of 1980 presidential elections in the U.S. by the Soviet television

Election of 1980 in Counting the Votes

{{Authority control 1980 United States Presidential Election 1980 Ronald Reagan Jimmy Carter Walter Mondale George H. W. Bush November 1980 events in the United States

presidential election

A presidential election is the election of any head of state whose official title is President.

Elections by country

Albania

The president of Albania is elected by the Assembly of Albania who are elected by the Albanian public.

Chile

The pre ...

. It was held on Tuesday, November 4, 1980. Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

nominee Ronald Reagan defeated incumbent Democratic President Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 76th governor of Georgia from 1 ...

in a landslide victory. This was the second successive election in which the incumbent president was defeated, after Carter himself defeated Gerald Ford four years earlier in 1976

Events January

* January 3 – The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights enters into force.

* January 5 – The Pol Pot regime proclaims a new constitution for Democratic Kampuchea.

* January 11 – The 1976 ...

, marking only the second time in American history that this occurred, after 1892

Events

January–March

* January 1 – Ellis Island begins accommodating immigrants to the United States.

* February 1 - The historic Enterprise Bar and Grill was established in Rico, Colorado.

* February 27 – Rudolf Diesel applies fo ...

. Additionally, it was only the third time an incumbent Democrat lost re-election, and only the second (and last) time a Republican has defeated an incumbent Democrat. Additionally, this was only the second time in history that an incumbent Democrat lost the popular vote, after 1840, and the only time it occurred against a Republican. Due to the rise of conservatism

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

following Reagan's victory, some historians consider the election to be a political realignment

A political realignment, often called a critical election, critical realignment, or realigning election, in the academic fields of political science and political history, is a set of sharp changes in party ideology, issues, party leaders, regional ...

that began with Barry Goldwater's presidential campaign in 1964, and the 1980 election marked the start of the Reagan Era.

Carter's unpopularity and poor relations with Democratic leaders encouraged an intra-party challenge by Senator Ted Kennedy

Edward Moore Kennedy (February 22, 1932 – August 25, 2009) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States senator from Massachusetts for almost 47 years, from 1962 until his death in 2009. A member of the Democratic ...

, a younger brother of President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

. Carter defeated Kennedy in the majority of the Democratic primaries, but Kennedy remained in the race until Carter was officially nominated at the 1980 Democratic National Convention. The Republican primaries were contested between Reagan, who had previously served as the Governor of California, former Congressman George H. W. Bush of Texas, Congressman John B. Anderson of Illinois, and several other candidates. All of Reagan's opponents had dropped out by the end of the primaries, and the 1980 Republican National Convention nominated a ticket consisting of Reagan and Bush. Anderson entered the race as an independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independ ...

candidate, and convinced former Wisconsin Governor Patrick Lucey

Patrick Joseph Lucey (March 21, 1918 – May 10, 2014) was an American politician. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as the 38th Governor of Wisconsin from 1971 to 1977. He was also independent presidential candidate John B. Anderso ...

, a Democrat, to serve as his running mate. Reagan campaigned for increased defense spending, implementation of supply-side economic policies, and a balanced budget. His campaign was aided by Democratic dissatisfaction with Carter, the Iran hostage crisis

On November 4, 1979, 52 United States diplomats and citizens were held hostage after a group of militarized Iranian college students belonging to the Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line, who supported the Iranian Revolution, took over ...

, and a worsening economy at home marked by high unemployment and inflation. Carter attacked Reagan as a dangerous right-wing extremist, and warned that Reagan would cut Medicare and Social Security

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifical ...

.

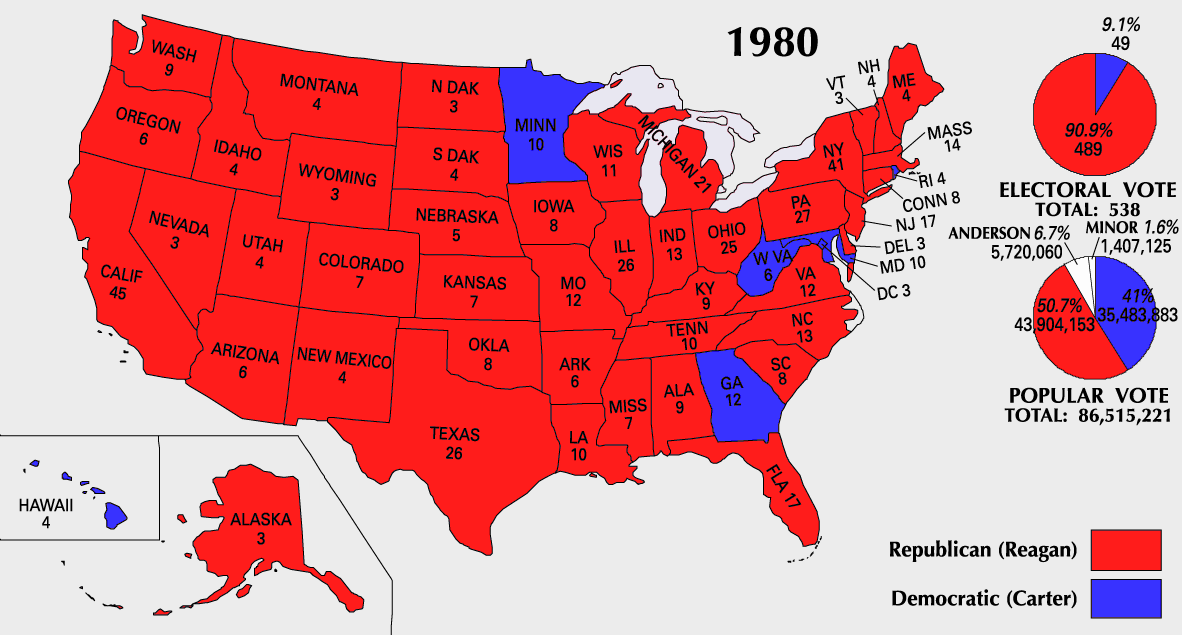

Reagan won the election by a landslide, taking 489 electoral votes and 50.8% of the popular vote with a margin of 9.7%. Reagan received the highest number of electoral votes ever won by a non-incumbent presidential candidate. In the simultaneous Congressional elections, Republicans won control of the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

for the first time since 1955. Carter won 41% of the vote, but carried just six states and Washington, D. C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, Na ...

Anderson won 6.6% of the popular vote, and he performed best among liberal Republican voters dissatisfied with Reagan. Reagan, then 69, was the oldest person to ever be elected to a first term, beating William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

's record in 1840.

Background

Throughout the 1970s, the United States underwent a wrenching period of low economic growth, high inflation and interest rates, and intermittent energy crises. By October 1978,Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

—a major oil supplier to the United States at the time—was experiencing a major uprising that severely damaged its oil infrastructure and greatly weakened its capability to produce oil. In January 1979, shortly after Iran's leader Shah

Shah (; fa, شاه, , ) is a royal title that was historically used by the leading figures of Iranian monarchies.Yarshater, EhsaPersia or Iran, Persian or Farsi, ''Iranian Studies'', vol. XXII no. 1 (1989) It was also used by a variety of ...

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi fled the country, Iranian opposition figure Ayatollah

Ayatollah ( ; fa, آیتالله, āyatollāh) is an honorific title for high-ranking Twelver Shia clergy in Iran and Iraq that came into widespread usage in the 20th century.

Etymology

The title is originally derived from Arabic word p ...

Ruhollah Khomeini ended his 14-year exile in France and returned to Iran to establish an Islamic Republic, largely hostile to American interests and influence in the country. In the spring and summer of 1979, inflation was on the rise and various parts of the United States were experiencing energy shortages.

Carter was widely blamed for the return of the long gas lines in the summer of 1979 that was last seen just after the 1973 Yom Kippur War

The Yom Kippur War, also known as the Ramadan War, the October War, the 1973 Arab–Israeli War, or the Fourth Arab–Israeli War, was an armed conflict fought from October 6 to 25, 1973 between Israel and a coalition of Arab states led by E ...

. He planned on delivering his fifth major speech on energy, but he felt that the American people were no longer listening. Carter left for the presidential retreat of Camp David. "For more than a week, a veil of secrecy enveloped the proceedings. Dozens of prominent Democratic Party leaders—members of Congress

A Member of Congress (MOC) is a person who has been appointed or elected and inducted into an official body called a congress, typically to represent a particular constituency in a legislature. The term member of parliament (MP) is an equivalen ...

, governors, labor leaders, academics and clergy—were summoned to the mountaintop retreat to confer with the beleaguered president." His pollster, Pat Caddell

Patrick Hayward Caddell (May 19, 1950 – February 16, 2019) was an American public opinion pollster and a political film consultant who served in the Carter administration. He worked for Democratic presidential candidates George McGovern ...

, told him that the American people simply faced a crisis of confidence because of the assassinations of John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

, Robert F. Kennedy

Robert Francis Kennedy (November 20, 1925June 6, 1968), also known by his initials RFK and by the nickname Bobby, was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 64th United States Attorney General from January 1961 to September 1964, ...

and Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

; the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam a ...

; and Watergate. On July 15, 1979, Carter gave a nationally televised address in which he identified what he believed to be a "crisis of confidence" among the American people. This came to be known as his " Malaise speech", although Carter never used the word in the speech.

Many expected Senator Ted Kennedy to successfully challenge Carter in the upcoming Democratic primary. Kennedy's official announcement was scheduled for early November. A television interview with Roger Mudd of CBS a few days before the announcement went badly, however. Kennedy gave an "incoherent and repetitive" answer to the question of why he was running, and the polls, which showed him leading the President by 58–25 in August now had him ahead 49–39.

Meanwhile, Carter was given an opportunity for political redemption when the Khomeini regime again gained public attention and allowed the taking of 52 American hostages by a group of Islamist students and militants at the U.S. embassy in Tehran

Tehran (; fa, تهران ) is the largest city in Tehran Province and the capital of Iran. With a population of around 9 million in the city and around 16 million in the larger metropolitan area of Greater Tehran, Tehran is the most popul ...

on November 4, 1979. Carter's calm approach towards the handling of this crisis resulted in his approval ratings jump in the 60-percent range in some polls, due to a "rally round the flag" effect.

By the beginning of the election campaign, the prolonged Iran hostage crisis

On November 4, 1979, 52 United States diplomats and citizens were held hostage after a group of militarized Iranian college students belonging to the Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line, who supported the Iranian Revolution, took over ...

had sharpened public perceptions of a national crisis. On April 25, 1980, Carter's ability to use the hostage crisis to regain public acceptance eroded when his high risk attempt to rescue the hostages ended in disaster when eight servicemen were killed. The unsuccessful rescue attempt drew further skepticism towards his leadership skills.

Following the failed rescue attempt, Carter took overwhelming blame for the Iran hostage crisis, in which the followers of the Ayatollah Khomeini burned American flags

The national flag of the United States of America, often referred to as the ''American flag'' or the ''U.S. flag'', consists of thirteen equal horizontal stripes of red (top and bottom) alternating with white, with a blue rectangle in the ...

and chanted anti-American slogans, paraded the captured American hostages in public, and burned Carter in effigy. Carter's critics saw him as an inept leader who had failed to solve the worsening economic problems at home. His supporters defended the president as a decent, well-intentioned man being unfairly criticized for problems that had been escalating for years.

When the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in late 1979, Carter seized international leadership in rallying opposition. He cut off American grain sales, which hurt Soviet consumers and annoyed American famers. In terms of prestige the Soviets were deeply hurt by the large-scale boycott of their 1980 Summer Olympics. Furthermore Carter began secret support of the opposition forces in Afghanistan that successfully tied down the Soviet army for a decade. The effect was to end détente and reopen the Cold War.

Nominations

Republican Party

Other major candidates

The following candidates were frequently interviewed by major broadcast networks and cable news channels, were listed in publicly published national polls, or had held a public office. Reagan received 7,709,793 votes in the primaries. Former governor Ronald Reagan ofCalifornia

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

was the odds-on favorite to win his party's nomination for president after nearly beating incumbent President Gerald Ford just four years earlier. Reagan dominated the primaries early, driving from the field Senate Minority Leader Howard Baker from Tennessee, former governor John Connally

John Bowden Connally Jr. (February 27, 1917June 15, 1993) was an American politician. He served as the 39th governor of Texas and as the 61st United States secretary of the Treasury. He began his career as a Democrat and later became a Republic ...

of Texas, Senator Robert Dole

Robert Joseph Dole (July 22, 1923 – December 5, 2021) was an American politician and attorney who represented Kansas in the United States Senate from 1969 to 1996. He was the Republican Leader of the Senate during the final 11 years of his t ...

from Kansas, Representative Phil Crane

Philip Miller Crane (November 3, 1930 – November 8, 2014) was an American politician. He was a Republican member of the United States House of Representatives from 1969 to 2005, representing the 8th District of Illinois in the northwestern s ...

from Illinois, and Representative John Anderson from Illinois, who dropped out of the race to run as an Independent. George H. W. Bush from Texas posed the strongest challenge to Reagan with his victories in the Pennsylvania and Michigan primaries, but it was not enough to turn the tide. Reagan won the nomination on the first round at the 1980 Republican National Convention in Detroit, Michigan

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at ...

, in July, then chose Bush (his top rival) as his running mate. Reagan, Bush, and Dole would all go on to be the nominee in the next four elections. (Reagan in 1984

Events

January

* January 1 – The Bornean Sultanate of Brunei gains full independence from the United Kingdom, having become a British protectorate in 1888.

* January 7 – Brunei becomes the sixth member of the Association of Southeas ...

, Bush in 1988

File:1988 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: The oil platform Piper Alpha explodes and collapses in the North Sea, killing 165 workers; The USS Vincennes (CG-49) mistakenly shoots down Iran Air Flight 655; Australia celebrates its Bicenten ...

and 1992, and Dole in 1996)

Democratic Party

Other major candidates

The following candidates were frequently interviewed by major broadcast networks, were listed in published national polls, or had held public office. Carter received 10,043,016 votes in the primaries. The three major Democratic candidates in early 1980 were incumbent PresidentJimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 76th governor of Georgia from 1 ...

, Senator Ted Kennedy

Edward Moore Kennedy (February 22, 1932 – August 25, 2009) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States senator from Massachusetts for almost 47 years, from 1962 until his death in 2009. A member of the Democratic ...

of Massachusetts, and Governor Jerry Brown

Edmund Gerald Brown Jr. (born April 7, 1938) is an American lawyer, author, and politician who served as the 34th and 39th governor of California from 1975 to 1983 and 2011 to 2019. A member of the Democratic Party, he was elected Secretary of ...

of California. Brown withdrew on April 2. Carter and Kennedy faced off in 34 primaries. Not counting the 1968 election in which Lyndon Johnson withdrew his candidacy, this was the most tumultuous primary race that an elected incumbent president had encountered since President Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

, during the highly contentious election of 1912.

During the summer of 1980, there was a short-lived "Draft Muskie" movement; Secretary of State Edmund Muskie was seen as a favorable alternative to a deadlocked convention. One poll showed that Muskie would be a more popular alternative to Carter than Kennedy, implying that the attraction was not so much to Kennedy as to the fact that he was not Carter. Muskie was polling even with Ronald Reagan at the time, while Carter was seven points behind. Although the underground "Draft Muskie" campaign failed, it became a political legend.

After defeating Kennedy in 24 of 34 primaries, Carter entered the party's convention in New York in August with 60 percent of the delegates pledged to him on the first ballot. Still, Kennedy refused to drop out. At the convention, after a futile last-ditch attempt by Kennedy to alter the rules to free delegates from their first-ballot pledges, Carter was renominated with 2,129 votes to 1,146 for Kennedy. Vice President Walter Mondale

Walter Frederick "Fritz" Mondale (January 5, 1928 – April 19, 2021) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 42nd vice president of the United States from 1977 to 1981 under President Jimmy Carter. A U.S. senator from Minnesota ...

was also renominated. In his acceptance speech, Carter warned that Reagan's conservatism posed a threat to world peace and progressive social welfare programs from the New Deal to the Great Society

The Great Society was a set of domestic programs in the United States launched by Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964–65. The term was first coined during a 1964 commencement address by President Lyndon B. Johnson at the Universit ...

.

Other candidates

John B. Anderson was defeated in the Republican primaries, but entered the general election as an independent candidate. He campaigned as a liberal Republican alternative to Reagan's conservatism. Anderson's campaign appealed primarily to frustrated anti-Carter voters from Republican and Democratic backgrounds. Despite maintaining the support of millions of liberal, pro-ERA, anti-Reagan and anti-Carter voters all the way up to election day to finish third with 5.7 million votes, Anderson's poll ratings had ebbed away through the campaign season as many of his initial supporters were pulled away by Carter and Reagan. Anderson's running mate wasPatrick Lucey

Patrick Joseph Lucey (March 21, 1918 – May 10, 2014) was an American politician. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as the 38th Governor of Wisconsin from 1971 to 1977. He was also independent presidential candidate John B. Anderso ...

, a Democratic former Governor of Wisconsin and then ambassador to Mexico, appointed by President Carter.

The Libertarian Party

Active parties by country

Defunct parties by country

Organizations associated with Libertarian parties

See also

* Liberal parties by country

* List of libertarian organizations

* Lists of political parties

Lists of political part ...

nominated Ed Clark

Edward E. Clark (born May 4, 1930) is an American lawyer and politician who ran for governor of California in 1978, and for president of the United States as the nominee of the Libertarian Party in the 1980 presidential election.

Clark is an h ...

for president and David Koch

David Hamilton Koch ( ; May 3, 1940 – August 23, 2019) was an American businessman, political activist, philanthropist, and chemical engineer. In 1970, he joined the family business: Koch Industries, the second largest privately held c ...

for vice president. They received almost one million votes and were on the ballot in all 50 states plus Washington, D.C. Koch, a co-owner of Koch Industries

Koch Industries, Inc. ( ) is an American privately held multinational conglomerate corporation based in Wichita, Kansas and is the second-largest privately held company in the United States, after Cargill. Its subsidiaries are involved in the ...

, pledged part of his personal fortune to the campaign. The Libertarian Party platform was the only political party in 1980 to contain a plank advocating for the equal rights of homosexual men and women as well as the only party platform to advocate explicitly for "amnesty" for all illegal non-citizens.http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/platforms.php http://www.lpedia.org/1980_Libertarian_Party_Platform#3._Victimless_Crimes The platform was also unique in favoring the repeal of the National Labor Relations Act, all state Right to Work laws

In the context of labor law in the United States, the term "right-to-work laws" refers to state laws that prohibit union security agreements between employers and labor unions which require employees who are not union members to contribute t ...

, Medicare, Medicaid, and “the increasingly oppressive” Social Security. Clark emphasized his support for an end to the war on drugs

The war on drugs is a global campaign, led by the United States federal government, of drug prohibition, military aid, and military intervention, with the aim of reducing the illegal drug trade in the United States.Cockburn and St. Clair, 1 ...

. He advertised his opposition to the draft and wars of choice.

The Clark–Koch ticket received 921,128 votes (1.1% of the total nationwide), finishing in fourth place nationwide. This was the highest overall number of votes earned by a Libertarian candidate until the 2012 election

This national electoral calendar for 2012 lists the national/ federal elections held in 2012 in all sovereign states and their dependent territories. By-elections are excluded, though national referendums are included.

January

*3–4 January: ...

, when Gary Johnson

Gary Earl Johnson (born January 1, 1953) is an American businessman, author, and politician. He served as the 29th governor of New Mexico from 1995 to 2003 as a member of the Republican Party. He was the Libertarian Party nominee for Presid ...

and James P. Gray became the first Libertarian ticket to earn more than a million votes, albeit with a lower overall vote percentage than Clark–Koch. The 1980 total remained the highest percentage of popular votes a Libertarian Party candidate received in a presidential race until Johnson and William Weld received 3.3% of the popular vote in 2016

File:2016 Events Collage.png, From top left, clockwise: Bombed-out buildings in Ankara following the 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt; the Impeachment of Dilma Rousseff, impeachment trial of Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff; Damaged houses duri ...

. Clark's strongest support was in Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S. ...

, where he came in third place with 11.7% of the vote, finishing ahead of Independent candidate John B. Anderson and receiving almost half as many votes as Jimmy Carter.

The Socialist Party USA

The Socialist Party USA, officially the Socialist Party of the United States of America,"The article of this organization shall be the Socialist Party of the United States of America, hereinafter called 'the Party'". Art. I of th"Constitution o ...

nominated David McReynolds

David Ernest McReynolds (October 25, 1929 – August 17, 2018) was an American politician and social activist who was a prominent democratic socialist and pacifist activist. He described himself as "a peace movement bureaucrat" during his 40-yea ...

for president and Sister Diane Drufenbrock for vice president, making McReynolds the first openly gay man to run for president and Drufenbrock the first nun to be a candidate for national office in the U.S.

The Citizens Party ran biologist

A biologist is a scientist who conducts research in biology. Biologists are interested in studying life on Earth, whether it is an individual Cell (biology), cell, a multicellular organism, or a Community (ecology), community of Biological inter ...

Barry Commoner

Barry Commoner (May 28, 1917 – September 30, 2012) was an American cellular biologist, college professor, and politician. He was a leading ecologist and among the founders of the modern environmental movement. He was the director of the ...

for president and Comanche Native American activist LaDonna Harris

LaDonna Vita Tabbytite Harris (born February 26, 1931) is a Comanche Native American social activist and politician from Oklahoma.Fluharty, SterlingHarris, LaDonna Vita Tabbytite profile 'mOklahoma Historical Society Encyclopedia of Oklahoma H ...

for vice president. The Commoner–Harris ticket was on the ballot in twenty-nine states and in the District of Columbia

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

.

The Communist Party USA ran Gus Hall

Gus Hall (born Arvo Kustaa Halberg; October 8, 1910 – October 13, 2000) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) and a perennial candidate for president of the United States. He was the Communist Party nominee in the ...

for president and Angela Davis

Angela Yvonne Davis (born January 26, 1944) is an American political activist, philosopher, academic, scholar, and author. She is a professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz. A feminist and a Marxist, Davis was a longtime member of ...

for vice president.

The American Party nominated Percy L. Greaves Jr. for president and Frank L. Varnum for vice president.

Rock star Joe Walsh

Joseph Fidler Walsh (born November 20, 1947) is an American guitarist, singer, and songwriter. In a career spanning over five decades, he has been a member of three successful rock bands: the James Gang, Eagles, and Ringo Starr & His All-Starr ...

ran a mock campaign as a write-in candidate

A write-in candidate is a candidate whose name does not appear on the ballot but seeks election by asking voters to cast a vote for the candidate by physically writing in the person's name on the ballot. Depending on electoral law it may be poss ...

, promising to make his song " Life's Been Good" the new national anthem if he won, and running on a platform of "Free Gas For Everyone." Though the 33-year-old Walsh was not old enough to actually assume the office, he wanted to raise public awareness of the election.

General election

Campaign

Under federal election laws, Carter and Reagan received $29.4 million each, and Anderson was given a limit of $18.5 million with private fund-raising allowed for him only. They were not allowed to spend any other money. Carter and Reagan each spent about $15 million on television advertising, and Anderson under $2 million. Reagan ended up spending $29.2 million in total, Carter $29.4 million, and Anderson spent $17.6 million—partially because he (Anderson) didn't getFederal Election Commission

The Federal Election Commission (FEC) is an independent regulatory agency of the United States whose purpose is to enforce campaign finance law in United States federal elections. Created in 1974 through amendments to the Federal Election Cam ...

money until after the election.

The 1980 election marked a political realignment

A political realignment, often called a critical election, critical realignment, or realigning election, in the academic fields of political science and political history, is a set of sharp changes in party ideology, issues, party leaders, regional ...

, with Reagan gaining in former Democratic strongholds such as the South and white ethnics (dubbed "Reagan Democrats

A Reagan Democrat is a traditionally Democratic Party (United States), Democratic voter in the Northern United States, referring to working class residents who supported Republican Party (United States), Republican presidential candidates Ronald R ...

." Reagan exuded upbeat optimism. David Frum

David Jeffrey Frum (; born June 30, 1960) is a Canadian-American political commentator and a former speechwriter for President George W. Bush, who is currently a senior editor at ''The Atlantic'' as well as an MSNBC contributor. In 2003, Frum a ...

says Carter ran an attack-based campaign based on "despair and pessimism" which "cost him the election." Carter emphasized his record as a peacemaker, and said Reagan's election would threaten civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life o ...

and social programs that stretched back to the New Deal. Reagan's platform also emphasized the importance of peace, as well as a prepared self-defense.

Immediately after the conclusion of the primaries, a Gallup poll

Gallup, Inc. is an American analytics and advisory company based in Washington, D.C. Founded by George Gallup in 1935, the company became known for its public opinion polls conducted worldwide. Starting in the 1980s, Gallup transitioned its ...

held that Reagan was ahead, with 58% of voters upset by Carter's handling of the Presidency. One analysis of the election has suggested that "Both Carter and Reagan were perceived negatively by a majority of the electorate." While the three leading candidates (Reagan, Anderson and Carter) were religious Christians, Carter had the most support of evangelical Christians according to a Gallup poll. However, in the end, Jerry Falwell's Moral Majority

Moral Majority was an American political organization associated with the Christian right and Republican Party. It was founded in 1979 by Baptist minister Jerry Falwell Sr. and associates, and dissolved in the late 1980s. It played a key role in ...

lobbying group is credited with giving Reagan two-thirds of the white evangelical vote. According to Carter: "that autumn 980a group headed by Jerry Falwell purchased $10 million in commercials on southern radio and TV to brand me as a traitor to the South and no longer a Christian."

The election of 1980 was a key turning point in American politics. It signaled the new electoral power of the suburbs and the Sun Belt. Reagan's success as a conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

would initiate a realigning of the parties, as liberal Republicans and conservative Democrats

In American politics, a conservative Democrat is a member of the Democratic Party with conservative political views, or with views that are conservative compared to the positions taken by other members of the Democratic Party. Traditionally, co ...

would either leave politics or change party affiliations through the 1980s and 1990s to leave the parties much more ideologically polarized. While during Barry Goldwater's 1964 campaign, many voters saw his warnings about a too-powerful government as hyperbolic and only 30% of the electorate agreed that government was too powerful, by 1980 a majority of Americans believed that government held too much power.

Promises

Reagan promised a restoration of the nation's military strength, at the same time 60% of Americans polled felt defense spending was too low. Reagan also promised an end to "trust me government" and to restore economic health by implementing a supply-side economic policy. Reagan promised a balanced budget within three years (which he said would be "the beginning of the end of inflation"), accompanied by a 30% reduction in tax rates over those same years. With respect to the economy, Reagan famously said, "A recession is when your neighbor loses his job. A depression is when you lose yours. And recovery is when Jimmy Carter loses his." Reagan also criticized the " windfall profit tax" that Carter and Congress enacted that year in regards to domestic oil production and promised to attempt to repeal it as president. The tax was not a tax on profits, but on the difference between theprice control

Price controls are restrictions set in place and enforced by governments, on the prices that can be charged for goods and services in a market. The intent behind implementing such controls can stem from the desire to maintain affordability of good ...

-mandated price and the market price.

On the issue of women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, ...

there was much division, with many feminists frustrated with Carter, the only major-party candidate who supported the Equal Rights Amendment. After a bitter Convention fight between Republican feminists and antifeminists the Republican Party dropped their forty-year endorsement of the ERA. Reagan, however, announced his dedication to women's rights and his intention to, if elected, appoint women to his cabinet and the first female justice to the Supreme Court. He also pledged to work with all 50 state governors to combat discrimination against women and to equalize federal laws as an alternative to the ERA. Reagan was convinced to give an endorsement of women's rights in his nomination acceptance speech.

Carter was criticized by his own aides for not having a "grand plan" for the recovery of the economy, nor did he ever make any campaign promises; he often criticized Reagan's economic recovery plan, but did not create one of his own in response.

Events

In August, after the Republican National Convention, Ronald Reagan gave a campaign speech at the annual Neshoba County Fair on the outskirts of

In August, after the Republican National Convention, Ronald Reagan gave a campaign speech at the annual Neshoba County Fair on the outskirts of Philadelphia, Mississippi

Philadelphia is a city in and the county seat of Neshoba County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 7,118 at the 2020 census.

History

Philadelphia is incorporated as a municipality; it was given its current name in 1903, two years ...

, where three civil rights workers were murdered in 1964. He was the first presidential candidate ever to campaign at the fair. Reagan famously announced, "Programs like education and others should be turned back to the states and local communities with the tax sources to fund them. I believe in states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the ...

. I believe in people doing as much as they can at the community level and the private level." Reagan also stated, "I believe we have distorted the balance of our government today by giving powers that were never intended to be given in the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

to that federal establishment." He went on to promise to "restore to states and local governments the power that properly belongs to them." President Carter criticized Reagan for injecting "hate and racism" by the "rebirth of code words like 'states' rights'".

Two days later, Reagan appeared at the

Two days later, Reagan appeared at the Urban League

The National Urban League, formerly known as the National League on Urban Conditions Among Negroes, is a nonpartisan historic civil rights organization based in New York City that advocates on behalf of economic and social justice for African Am ...

convention in New York, where he said, "I am committed to the protection and enforcement of the civil rights of black Americans. This commitment is interwoven into every phase of the plans I will propose." He then said that he would develop " enterprise zones" to help with urban renewal.

The media's main criticism of Reagan centered on his gaffes. When Carter kicked off his general election campaign in Tuscumbia, Reagan—referring to the Southern U.S. as a whole—claimed that Carter had begun his campaign in the birthplace of the Ku Klux Klan. In doing so, Reagan seemed to insinuate that the KKK represented the South, which caused many Southern governors to denounce Reagan's remarks. Additionally, Reagan was widely ridiculed by Democrats for saying that trees caused pollution; he later said that he meant only certain types of pollution and his remarks had been misquoted.

Meanwhile, Carter was burdened by a continued weak economy and the Iran hostage crisis

On November 4, 1979, 52 United States diplomats and citizens were held hostage after a group of militarized Iranian college students belonging to the Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line, who supported the Iranian Revolution, took over ...

. Inflation, high interest rates, and unemployment continued through the course of the campaign, and the ongoing hostage crisis in Iran became, according to David Frum

David Jeffrey Frum (; born June 30, 1960) is a Canadian-American political commentator and a former speechwriter for President George W. Bush, who is currently a senior editor at ''The Atlantic'' as well as an MSNBC contributor. In 2003, Frum a ...

in ''How We Got Here: The '70s'', a symbol of American impotence during the Carter years. John Anderson's independent candidacy, aimed at eliciting support from liberals, was also seen as hurting Carter more than Reagan, especially in reliably Democratic states such as Massachusetts and New York.

Presidential debates

The League of Women Voters, which had sponsored the 1976 Ford/Carter debate series, announced that it would do so again for the next cycle in the spring of 1979. However, Carter was not eager to participate with any debate. He had repeatedly refused to a debate with Senator Edward M. Kennedy during the primary season, and had given ambivalent signals as to his participation in the fall. The League of Women Voters had announced a schedule of debates similar to 1976, three presidential and one vice presidential. No one had much of a problem with this until it was announced that Rep. John B. Anderson might be invited to participate along with Carter and Reagan. Carter steadfastly refused to participate with Anderson included, and Reagan refused to debate without him. It took months of negotiations for the League of Women Voters to finally put it together. It was held on September 21, 1980, in theBaltimore Convention Center

The Baltimore Convention Center is a convention and exhibition hall located in downtown Baltimore, Maryland. The center is a municipal building owned and operated by the City of Baltimore.

The facility was constructed in two separate phases: th ...

. Reagan said of Carter's refusal to debate: "He arter

Arter is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Harry Arter

* Jared Maurice Arter

* Kingsley Arter Taft

* Philip and Uriah Arter, after whom Philip and Uriah Arter Farm is named

* Robert Arter

* Solomon Arter, after whom Solomon ...

knows that he couldn't win a debate even if it were held in the Rose Garden

A rose garden or rosarium is a garden or park, often open to the public, used to present and grow various types of garden roses, and sometimes rose species. Most often it is a section of a larger garden. Designs vary tremendously and roses m ...

before an audience of Administration officials with the questions being asked by Jody Powell

Joseph Lester "Jody" Powell, Jr. (September 30, 1943 – September 14, 2009) was an American political advisor who served as a White House press secretary during the presidency of Jimmy Carter. Powell later co-founded a public relations firm.

E ...

." The League of Women Voters promised the Reagan campaign that the debate stage would feature an empty chair to represent the missing president. Carter was very upset about the planned chair stunt, and at the last minute convinced the league to take it out. The debate was moderated by Bill Moyers

Bill Moyers (born Billy Don Moyers, June 5, 1934) is an American journalist and political commentator. Under the Johnson administration he served from 1965 to 1967 as the eleventh White House Press Secretary. He was a director of the Counci ...

. Anderson, who many thought would handily dispatch Reagan, managed only a narrow win, according to many in the media at that time, with Reagan putting up a much stronger performance than expected. Despite the narrow win in the debate, Anderson, who had been as high as 20% in some polls, and at the time of the debate was over 10%, dropped to about 5% soon after, although Anderson got back up to winning 6.6% of the vote on election day. In the debate, Anderson failed to substantively engage Reagan enough on their social issue differences and on Reagan's advocation of supply-side economics. Anderson instead started off by criticizing Carter: "Governor Reagan is not responsible for what has happened over the last four years, nor am I. The man who should be here tonight to respond to those charges chose not to attend," to which Reagan added: "It's a shame now that there are only two of us here debating, because the two that are here are in more agreement than disagreement." In one moment in the debate, Reagan commented on a rumor that Anderson had invited Senator Ted Kennedy

Edward Moore Kennedy (February 22, 1932 – August 25, 2009) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States senator from Massachusetts for almost 47 years, from 1962 until his death in 2009. A member of the Democratic ...

to be his running mate by asking the candidate directly, "John, would you really prefer Teddy Kennedy to me?"

As September turned into October, the situation remained essentially the same. Governor Reagan insisted Anderson be allowed to participate in a three-way debate, while President Carter remained steadfastly opposed to this. As the standoff continued, the second debate was canceled, as was the vice presidential debate.

With two weeks to go to the election, the Reagan campaign decided that the best thing to do at that moment was to accede to all of President Carter's demands, including that Anderson not feature, and LWV agreed to exclude Congressman Anderson from the final debate, which was rescheduled for October 28 in Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

, Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

.

The presidential debate between President Carter and Governor Reagan was moderated by Howard K. Smith and presented by the League of Women Voters. The showdown ranked among the highest ratings of any

The presidential debate between President Carter and Governor Reagan was moderated by Howard K. Smith and presented by the League of Women Voters. The showdown ranked among the highest ratings of any television

Television, sometimes shortened to TV, is a telecommunication medium for transmitting moving images and sound. The term can refer to a television set, or the medium of television transmission. Television is a mass medium for advertisin ...

program in the previous decade. Debate topics included the Iranian hostage crisis, and nuclear arms treaties and proliferation. Carter's campaign sought to portray Reagan as a reckless "war hawk," as well as a "dangerous right-wing radical". But it was President Carter's reference to his consultation with 12-year-old daughter Amy concerning nuclear weapons policy that became the focus of post-debate analysis and fodder for late-night television joke

A joke is a display of humour in which words are used within a specific and well-defined narrative structure to make people laughter, laugh and is usually not meant to be interpreted literally. It usually takes the form of a story, often with ...

s. President Carter said he had asked Amy what the most important issue in that election was and she said, "the control of nuclear arms

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either nuclear fission, fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and nuclear fusion, fusion reactions (Thermonuclear weapon, thermonu ...

." A famous political cartoon, published the day after Reagan's landslide victory, showed Amy Carter sitting in Jimmy's lap with her shoulders shrugged asking "the economy? the hostage crisis?"

When President Carter criticized Reagan's record, which included voting against Medicare and Social Security

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifical ...

benefits, Governor Reagan audibly sighed and replied: "There you go again

"There you go again" was a phrase spoken during the second presidential debate of 1980 by Republican presidential candidate Ronald Reagan to his Democratic opponent, incumbent President Jimmy Carter. Reagan would use the line in a few debates ...

".

In describing the national debt that was approaching $1 trillion, Reagan stated "a billion is a thousand millions, and a trillion is a thousand billions." When Carter would criticize the content of Reagan's campaign speeches, Reagan began his counter with the words: "Well ... I don't know that I said that. I really don't."

In his closing remarks, Reagan asked viewers: "Are you better off now than you were four years ago? Is it easier for you to go and buy things in the stores than it was four years ago? Is there more or less unemployment in the country than there was four years ago? Is America as respected throughout the world as it was? Do you feel that our security is as safe, that we're as strong as we were four years ago? And if you answer all of those questions 'yes', why then, I think your choice is very obvious as to whom you will vote for. If you don't agree, if you don't think that this course that we've been on for the last four years is what you would like to see us follow for the next four, then I could suggest another choice that you have."

After trailing Carter by 8 points among registered voters (and by 3 points among likely voters) right before their debate, Reagan moved into a 3-point lead among likely voters immediately afterward.

Endorsements

In September 1980, formerWatergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon from 1972 to 1974 that led to Nixon's resignation. The scandal stemmed from the Nixon administration's contin ...

prosecutor Leon Jaworski

Leonidas "Leon" Jaworski (September 19, 1905 – December 9, 1982) was an American attorney and law professor who served as the second special prosecutor during the Watergate Scandal. He was appointed to that position on November 1, 1973, soon a ...

accepted a position as honorary chairman of Democrats for Reagan. Five months earlier, Jaworski had harshly criticized Reagan as an "extremist"; he said after accepting the chairmanship, "I would rather have a competent extremist than an incompetent moderate."

Former Democratic Senator Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota (who in 1968

The year was highlighted by protests and other unrests that occurred worldwide.

Events January–February

* January 5 – " Prague Spring": Alexander Dubček is chosen as leader of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia.

* Janu ...

had challenged Lyndon Johnson from the left, causing the then-President to all but abdicate) endorsed Reagan.MacNeil-Lehrer NewsHour (December 12, 2005)Online NewsHour: "Remembering Sen. Eugene McCarthy"

December 12, 2005.

PBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcaster and non-commercial, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly funded nonprofit organization and the most prominent provider of educat ...

.

Three days before the November 4 voting in the election, the National Rifle Association endorsed a presidential candidate for the first time in its history, backing Reagan. Reagan had received the California Rifle and Pistol Association's Outstanding Public Service Award. Carter had appointed Abner J. Mikva, a fervent proponent of gun control, to a federal judgeship and had supported the Alaska Lands Bill, closing to hunting.

General election endorsements

Anderson had received endorsements from: ;Former officeholders * FormerRepresentative

Representative may refer to:

Politics

* Representative democracy, type of democracy in which elected officials represent a group of people

* House of Representatives, legislative body in various countries or sub-national entities

* Legislator, som ...

( Arizona's 2nd congressional district) and Interior Secretary

The United States secretary of the interior is the head of the United States Department of the Interior. The secretary and the Department of the Interior are responsible for the management and conservation of most federal land along with natural ...

Stewart Udall (D-AZ)

;Current and former state and local officials and party officeholders

:Massachusetts

* Middlesex County Sheriff John J. Buckley (D-MA)

* Former Massachusetts State Representative Francis W. Hatch Jr. (R-MA)

* Former Massachusetts Republican Party

The Massachusetts Republican Party (MassGOP) is the Massachusetts branch of the U.S. Republican Party.

In accordance with Massachusetts General Laws Chapter 52, the party is governed by a state committee which consists of one man and one woma ...

chairman Josiah Spaulding

Josiah Augustus "Si" Spaulding (December 21, 1922 – March 27, 1983) was an American businessman, attorney, and politician.

Education and military service

Spaulding graduated from the Hotchkiss School and Yale University in 1947, where he was ...

(R-MA)

;Celebrities, political activists, and political commentators

;Newspapers

* ''The Hutchinson News

''The Hutchinson News'' is a daily newspaper serving the city of Hutchinson, Kansas, United States. The publication was awarded the 1965 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service "for its courageous and constructive campaign, culminating in 1964, to bri ...

'' in Hutchinson, Kansas

Hutchinson is the largest city and county seat in Reno County, Kansas, United States, and located on the Arkansas River. It has been home to salt mines since 1887, thus its nickname of "Salt City", but locals call it "Hutch". As of the 2020 ...

* ''The Burlington Free Press

''The Burlington Free Press'' (sometimes referred to as "BFP" or "the Free Press") is a digital and print community news organization based in Burlington, Vermont, and owned by Gannett. It is one of the official "newspapers of record" for the St ...

'' in Burlington, VT

Burlington is the List of municipalities in Vermont, most populous city in the U.S. state of Vermont and the county seat, seat of Chittenden County, Vermont, Chittenden County. It is located south of the Canada–United States border and south ...

Carter had received endorsements from:

;Newspapers

* ''The Des Moines Register

''The Des Moines Register'' is the daily morning newspaper of Des Moines, Iowa.

History Early period

The first newspaper in Des Moines was the ''Iowa Star''. In July 1849, Barlow Granger began the paper in an abandoned log cabin by the junction ...

'' in Des Moines, Iowa

Des Moines () is the capital and the most populous city in the U.S. state of Iowa. It is also the county seat of Polk County. A small part of the city extends into Warren County. It was incorporated on September 22, 1851, as Fort Des Moines, ...

* The '' Penn State Daily Collegian'' in State College, Pennsylvania

State College is a home rule municipality in Centre County in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. It is a college town, dominated economically, culturally and demographically by the presence of the University Park campus of the Pennsylvania Sta ...

Commoner had received endorsements from:

;Celebrities, political activists, and political commentators

* Montgomery County precinct committeeman and Consumer Party Auditor General

An auditor general, also known in some countries as a comptroller general or comptroller and auditor general, is a senior civil servant charged with improving government accountability by auditing and reporting on the government's operations.

Freq ...

candidate Darcy Richardson (D-PA)

DeBerry had received endorsements from:

;Celebrities, political activists and political commentators

* American People's Historical Society director Bernie Sanders of Vermont

Vermont () is a state in the northeast New England region of the United States. Vermont is bordered by the states of Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, and New York to the west, and the Canadian province of Quebec to ...

Reagan had received endorsements from:

;United States Senate

* Arizona Senator Dennis DeConcini (D-AZ)

* Virginia Senator Harry Byrd Jr. (D-VA)

* New York Senator Jacob Javits

Jacob Koppel Javits ( ; May 18, 1904 – March 7, 1986) was an American lawyer and politician. During his time in politics, he represented the state of New York in both houses of the United States Congress. A member of the Republican Party, he al ...

(R-NY)

*Former Massachusetts Senator Edward Brooke

Edward William Brooke III (October 26, 1919 – January 3, 2015) was an American politician of the Republican Party, who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1967 until 1979. Prior to serving in the Senate, he served as th ...

(R-MA)

;United States House of Representatives

* Representative

Representative may refer to:

Politics

* Representative democracy, type of democracy in which elected officials represent a group of people

* House of Representatives, legislative body in various countries or sub-national entities

* Legislator, som ...

(California's 12th congressional district

California's 12th congressional district is a congressional district in northern California. Speaker of the United States House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi, a Democrat, has represented the district since January 2013. She has represented ...

) Pete McCloskey

Paul Norton McCloskey Jr. (born September 29, 1927) is an American politician who represented San Mateo County, California as a Republican in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1967 to 1983.

Born in Loma Linda, California, McCloskey pursue ...

(R-CA)

* Former Representative

Representative may refer to:

Politics

* Representative democracy, type of democracy in which elected officials represent a group of people

* House of Representatives, legislative body in various countries or sub-national entities

* Legislator, som ...

(California's 26th congressional district

California 26th congressional district is a congressional district in the U.S. state of California currently represented by .

The district is located on the South Coast, comprising most of Ventura County as well as a small portion of Los Ange ...

) James Roosevelt

James Roosevelt II (December 23, 1907 – August 13, 1991) was an American businessman, Marine, activist, and Democratic Party politician. The eldest son of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt, he served as an official Secr ...

(D-CA; son of Franklin Delano Roosevelt)

;Governors and State Constitutional officers

* Former Georgia Governor

The governor of Georgia is the head of government of Georgia and the commander-in-chief of the state's military forces. The governor also has a duty to enforce state laws, the power to either veto or approve bills passed by the Georgia Legisl ...

Lester Maddox

Lester Garfield Maddox Sr. (September 30, 1915 – June 25, 2003) was an American politician who served as the 75th governor of the U.S. state of Georgia from 1967 to 1971. A populist Democrat, Maddox came to prominence as a staunch segregatio ...

(D-GA)

* Former Alabama Governor John Malcolm Patterson

John Malcolm Patterson (September 27, 1921 – June 4, 2021) was an American politician. Despite having never stood for public office before he served one term as Attorney General of Alabama from 1955 to 1959, and, at age 37, served one term as ...

(D-AL)

* Former Texas Governor

The governor of Texas heads the state government of Texas. The governor is the leader of the executive and legislative branch of the state government and is the commander in chief of the Texas Military. The current governor is Greg Abbott, who ...

Preston Smith Preston Smith may refer to:

* Preston Smith (American football coach) (1871–1945), American football coach at Colgate University

* Preston Smith (linebacker) (born 1992), American football outside linebacker

* Preston Smith (governor) (1912–20 ...

(D-TX)

* Former Mississippi Governor John Bell Williams

John Bell Williams (December 4, 1918 – March 25, 1983) was an American Democratic politician who represented Mississippi in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1947 to 1968 and served as Governor of Mississippi from 1968 to 1972.

He was f ...

(D-MS)

;Current and former state and local officials and party officeholders

:Florida

* Fort Lauderdale

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

City Advisory Board member Jim Naugle

James T. Naugle (born 1954) is an American real estate broker who served as mayor of Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Although a lifelong Democrat, Naugle frequently voted for and supported Republican candidates. Elected for the first time in 1991, Nau ...

(D-FL)

:New York

* Former New York State Senator

The New York State Senate is the upper house of the New York State Legislature; the New York State Assembly is its lower house. Its members are elected to two-year terms; there are no term limits. There are 63 seats in the Senate.

Partisan compo ...

Jeremiah B. Bloom (D-NY)

;Celebrities, political activists and political commentators

* Former UCLA men's basketball head coach John Wooden

* Retired United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

Admiral Elmo Zumwalt

Elmo Russell "Bud" Zumwalt Jr. (November 29, 1920 – January 2, 2000) was a United States Navy officer and the youngest person to serve as Chief of Naval Operations. As an admiral and later the 19th Chief of Naval Operations, Zumwalt played a m ...

(D-VA)

;Newspaper endorsements

* ''The Arizona Republic

''The Arizona Republic'' is an American daily newspaper published in Phoenix. Circulated throughout Arizona, it is the state's largest newspaper. Since 2000, it has been owned by the Gannett newspaper chain. Copies are sold at $2 daily or at $3 ...

'' in Phoenix, Arizona

Phoenix ( ; nv, Hoozdo; es, Fénix or , yuf-x-wal, Banyà:nyuwá) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Arizona, with 1,608,139 residents as of 2020. It is the fifth-most populous city in the United States, and the on ...

* ''The Desert Sun

''The Desert Sun'' is a local daily newspaper serving Palm Springs and the surrounding Coachella Valley in Southern California.

History

''The Desert Sun'' is owned by Gannett publications since 1988 and acquired the Indio ''Daily News'' in 1 ...

'' in Palm Springs, California

* The ''Omaha World-Herald

The ''Omaha World-Herald'' is a daily newspaper in the midwestern United States, the primary newspaper of the Omaha-Council Bluffs metropolitan area. It was locally owned from its founding in 1885 until 2020, when it was sold to the newspaper ch ...

in Omaha, Nebraska

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest cit ...

* The ''Quad-City Times

The ''Quad-City Times'' is a daily morning newspaper based in Davenport, Iowa, and circulated throughout the Quad Cities metropolitan area (Davenport, Bettendorf and Scott County in Iowa; and Moline, East Moline, Rock Island and Rock Isla ...

'' in Davenport, Iowa

* '' The Record'' in Stockton, California

* ''The Repository

''The Repository'' is an American daily local newspaper serving the Canton, Ohio area. It is currently owned by Gannett.

History

Historically, the newspaper had strong Republican connections, most notably with President William McKinley, who wa ...

'' in Canton, Ohio

* ''The Plain Dealer

''The Plain Dealer'' is the major newspaper of Cleveland, Ohio, United States. In fall 2019, it ranked 23rd in U.S. newspaper circulation, a significant drop since March 2013, when its circulation ranked 17th daily and 15th on Sunday.

As of Ma ...

'' in Cleveland, Ohio

* '' The Blade'' in Toledo, Ohio

Toledo ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Lucas County, Ohio, United States. A major Midwestern United States port city, Toledo is the fourth-most populous city in the state of Ohio, after Columbus, Cleveland, and Cincinnati, and according ...

* ''Houston Chronicle

The ''Houston Chronicle'' is the largest daily newspaper in Houston, Texas, United States. , it is the third-largest newspaper by Sunday circulation in the United States, behind only ''The New York Times'' and the ''Los Angeles Times''. With i ...

'' in Houston, Texas

* '' Richmond Times-Dispatch'' in Richmond, Virginia

Results

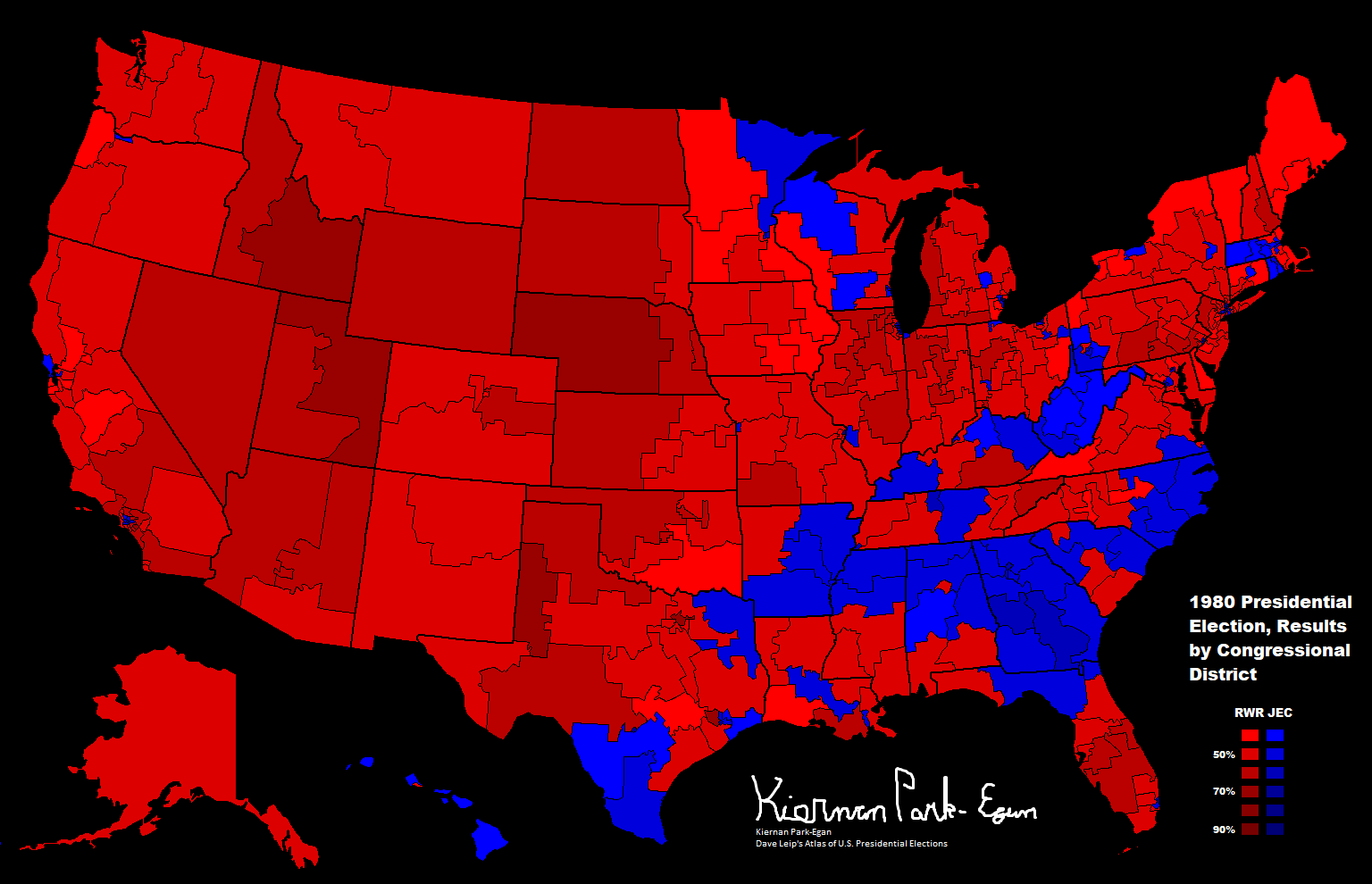

The election was held on November 4, 1980. Ronald Reagan and running mate George H. W. Bush beat Carter by almost 10 percentage points in the popular vote. Republicans also gained control of the Senate on

The election was held on November 4, 1980. Ronald Reagan and running mate George H. W. Bush beat Carter by almost 10 percentage points in the popular vote. Republicans also gained control of the Senate on Reagan's coattails

Reagan's coattails refers to the influence of Ronald Reagan's popularity in elections other than his own, after the American political expression to " ride in on another's coattails". Chiefly, it refers to the "Reagan Revolution" accompanying his ...

for the first time since 1952. The electoral college vote was a landslide, with 489 votes (representing 44 states) for Reagan and 49 for Carter (representing six states and Washington, D.C.). NBC News

NBC News is the news division of the American broadcast television network NBC. The division operates under NBCUniversal Television and Streaming, a division of NBCUniversal, which is, in turn, a subsidiary of Comcast. The news division's var ...

projected Reagan as the winner at 8:15 pm EST (5:15 PST), before voting was finished in the West, based on exit polls

An election exit poll is a poll of voters taken immediately after they have exited the polling stations. A similar poll conducted before actual voters have voted is called an entrance poll. Pollsters – usually private companies working for ...

; it was the first time a broadcast network used exit polling to project a winner, and took the other broadcast networks by surprise. Carter conceded defeat at 9:50 pm EST. Some of Carter's advisors urged him to wait until 11:00 pm EST to allow poll results from the West Coast to come in, but Carter decided to concede earlier in order to avoid the impression that he was sulking. Speaker of the House Tip O'Neill

Thomas Phillip "Tip" O'Neill Jr. (December 9, 1912 – January 5, 1994) was an American politician who served as the 47th speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1977 to 1987, representing northern Boston, Massachusetts, as ...

angrily accused Carter of weakening the party's performance in the Senate elections for doing this. Carter's loss was the worst performance by an incumbent president since Herbert Hoover lost to Franklin D. Roosevelt by a margin of 18% in 1932, and his 49 electoral college votes were the fewest won by an incumbent since William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

won only 8 in 1912. Carter was the first incumbent Democrat to serve only one full term since James Buchanan and also the first to serve one full term, seek re-election, and lose since Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he ...

; Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

served two non-consecutive terms while Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

and Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

served one full term in addition to respectively taking over following the deaths of Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

and John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

.

Carter carried only Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

(his home state), Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over to ...

(Mondale's home state), Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only state ...

, West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the B ...

, Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the smallest U.S. state by area and the seventh-least populous, with slightly fewer than 1.1 million residents as of 2020, but it ...

, and the District of Columbia

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

.

John Anderson won 6.6% of the popular vote but failed to win any state outright. He found the most support in New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the Can ...

, fueled by liberal and moderate Republicans who felt Reagan was too far to the right and with voters who normally leaned Democratic but were dissatisfied with the policies of the Carter Administration. His best showing was in Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

, where he won 15% of the popular vote. Conversely, Anderson performed worst in the South, receiving under 2% of the popular vote in South Carolina, Louisiana, Alabama, and Mississippi. Anderson claims that he was accused of spoiling the election for Carter by receiving votes that might have otherwise been cast for Carter. However, 37 percent of Anderson voters polled preferred Reagan as their second choice. Even if all Anderson votes had gone for Carter, Reagan would have still held enough majorities and pluralities to maintain 331 electoral votes.

Libertarian Party

Active parties by country

Defunct parties by country

Organizations associated with Libertarian parties

See also

* Liberal parties by country

* List of libertarian organizations

* Lists of political parties

Lists of political part ...

candidate Ed Clark

Edward E. Clark (born May 4, 1930) is an American lawyer and politician who ran for governor of California in 1978, and for president of the United States as the nominee of the Libertarian Party in the 1980 presidential election.

Clark is an h ...