Tyrone Power on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

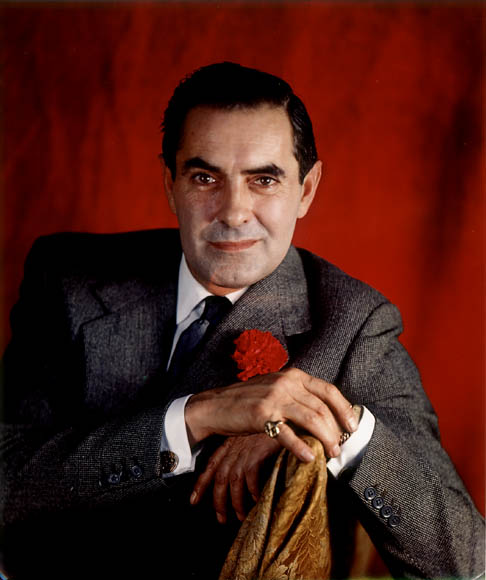

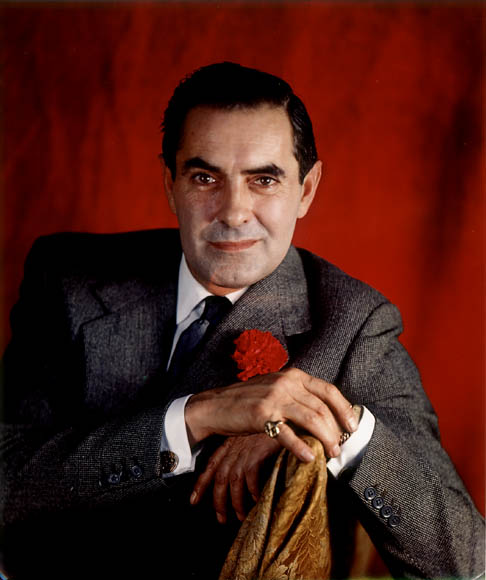

Tyrone Edmund Power III (May 5, 1914 – November 15, 1958) was an American actor. From the 1930s to the 1950s, Power appeared in dozens of films, often in

Power racked up hit after hit from 1936 until 1943, when his career was interrupted by military service. In these years he starred in romantic comedies such as '' Thin Ice'' and ''

Power racked up hit after hit from 1936 until 1943, when his career was interrupted by military service. In these years he starred in romantic comedies such as '' Thin Ice'' and ''

In 1940, the direction of Power's career took a dramatic turn when his movie '' The Mark of Zorro'' was released. Power played the role of Don Diego Vega/Zorro, a fop by day, a bandit hero by night. The role had been performed by Douglas Fairbanks in the 1920 movie of the same title. The film was a hit, and 20th Century Fox often cast Power in other swashbucklers in the years that followed. Power was a talented swordsman in real life, and the dueling scene in ''The Mark of Zorro'' is highly regarded. The great Hollywood swordsman,

In 1940, the direction of Power's career took a dramatic turn when his movie '' The Mark of Zorro'' was released. Power played the role of Don Diego Vega/Zorro, a fop by day, a bandit hero by night. The role had been performed by Douglas Fairbanks in the 1920 movie of the same title. The film was a hit, and 20th Century Fox often cast Power in other swashbucklers in the years that followed. Power was a talented swordsman in real life, and the dueling scene in ''The Mark of Zorro'' is highly regarded. The great Hollywood swordsman,

Other than re-releases of his films, Power was not seen on screen again after his entry into the Marines until 1946, when he co-starred with Gene Tierney, John Payne and

Other than re-releases of his films, Power was not seen on screen again after his entry into the Marines until 1946, when he co-starred with Gene Tierney, John Payne and

'' Untamed'' (1955) was Tyrone Power's last movie made under his contract with 20th Century-Fox. The same year saw the release of ''

'' Untamed'' (1955) was Tyrone Power's last movie made under his contract with 20th Century-Fox. The same year saw the release of ''

Power was one of Hollywood's most eligible bachelors until he married French actress Annabella (born Suzanne Georgette Charpentier) on July 14, 1939. They had met on the 20th Century Fox lot around the time they starred together in the movie ''Suez''. Power adopted Annabella's daughter, Anne, before leaving for service. In an

Power was one of Hollywood's most eligible bachelors until he married French actress Annabella (born Suzanne Georgette Charpentier) on July 14, 1939. They had met on the 20th Century Fox lot around the time they starred together in the movie ''Suez''. Power adopted Annabella's daughter, Anne, before leaving for service. In an

Power was interred at

Power was interred at

* ''Low and Behold'',

* ''Low and Behold'',

* '' Mister Roberts'', London Coliseum, England (195

http://tyforum.bravepages.com/ta/ta-mr.html] * ''John Brown's Body'', Broadway Century Theatre, NY (1952–1953) * ''The Dark is Light Enough'' (1955) * ''A Quiet Place'', The Playwrights Co. (1955–1956) * ''The Devil's Disciple'', Winter Garden Theatre, London, England (1956) * ''Back to Methuselah'', Ambassador Theatre (New York City), Ambassador Theatre, NY (1958)

Tyrone Power, King of 20th Century-Fox

*

Tyrone Power's newsreel appearances at the Associated Press Archive

Tyrone Power

at Virtual History {{DEFAULTSORT:Power, Tyrone 1914 births 1958 deaths Military personnel from Ohio 20th-century American male actors 20th Century Studios contract players American male film actors American male radio actors United States Marine Corps personnel of World War II American people of English descent American people of French-Canadian descent American people of German descent American people of Irish descent Burials at Hollywood Forever Cemetery Male actors from Cincinnati Power family United States Marine Corps officers United States Marine Corps reservists United States Marine Corps pilots of World War II LGBT male actors American LGBT actors Filmed deaths of entertainers

swashbuckler

A swashbuckler is a genre of European adventure literature that focuses on a heroic protagonist stock character who is skilled in swordsmanship, acrobatics, guile and possesses chivalrous ideals. A "swashbuckler" protagonist is heroic, daring, ...

roles or romantic leads. His better-known films include ''Jesse James

Jesse Woodson James (September 5, 1847April 3, 1882) was an American outlaw, bank and train robber, guerrilla and leader of the James–Younger Gang. Raised in the " Little Dixie" area of Western Missouri, James and his family maintained st ...

'', '' The Mark of Zorro'', ''Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette Josèphe Jeanne (; ; née Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last queen of France before the French Revolution. She was born an archduchess of Austria, and was the penultimate child a ...

'', '' Blood and Sand'', '' The Black Swan'', ''Prince of Foxes

''Prince of Foxes'' is a 1947 historical novel by Samuel Shellabarger, following the adventures of the fictional Andrea Orsini, a captain in the service of Cesare Borgia during his conquest of the Romagna.

Plot introduction

Andrea Zoppo, an Ita ...

'', ''Witness for the Prosecution

In law, a witness is someone who has knowledge about a matter, whether they have sensed it or are testifying on another witnesses' behalf. In law a witness is someone who, either voluntarily or under compulsion, provides testimonial evidence, e ...

'', '' The Black Rose'', and '' Captain from Castile''. Power's own favorite film among those that he starred in was '' Nightmare Alley''.

Though largely a matinee idol in the 1930s and early 1940s and known for his striking good looks, Power starred in films in a number of genres, from drama to light comedy

Comedy is a genre of fiction that consists of discourses or works intended to be humorous or amusing by inducing laughter, especially in theatre, film, stand-up comedy, television, radio, books, or any other entertainment medium. The term o ...

. In the 1950s he began placing limits on the number of films he would make in order to devote more time to theater productions. He received his biggest accolades as a stage actor in ''John Brown's Body

"John Brown's Body" (originally known as "John Brown's Song") is a United States marching song about the abolitionist John Brown. The song was popular in the Union during the American Civil War. The tune arose out of the folk hymn tradition o ...

'' and '' Mister Roberts''. Power died from a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which ma ...

at the age

Family background and early life

Power was born inCincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line w ...

, in 1914, the son of Helen Emma "Patia" (née Reaume) and the English-born American stage and screen actor Tyrone Power Sr.

Frederick Tyrone Edmond Power Sr. (2 May 1869 – 23 December 1931) was an English-born American stage and screen actor, known professionally as Tyrone Power. He is now usually referred to as Tyrone Power Sr. to differentiate him from his son ...

, often known by his first name "Fred". Power was descended from a long Irish theatrical line going back to his great-grandfather, the Irish actor and comedian Tyrone Power

Tyrone Edmund Power III (May 5, 1914 – November 15, 1958) was an American actor. From the 1930s to the 1950s, Power appeared in dozens of films, often in swashbuckler roles or romantic leads. His better-known films include ''Jesse James (193 ...

(1797–1841). Tyrone Power's sister, Ann Power, was born in 1915, after the family moved to California. His mother was Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

, and her ancestry included the French-Canadian Reaume family and French from Alsace-Lorraine. Through his paternal great-grandmother, Anne Gilbert, Power was related to the actor Laurence Olivier

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier (; 22 May 1907 – 11 July 1989) was an English actor and director who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud, was one of a trio of male actors who dominated the British stage ...

; through his paternal grandmother, stage actress Ethel Lavenu

Ethel Lavenu (1842 – 14 August 1917) was a British stage actress. She was the mother of stage and silent screen actor Tyrone Power, Sr., and grandmother of the Hollywood film star Tyrone Power.

Life and career

Born in Chelsea as Eliza Laven ...

, he was related by marriage to author Evelyn Waugh

Arthur Evelyn St. John Waugh (; 28 October 1903 – 10 April 1966) was an English writer of novels, biographies, and travel books; he was also a prolific journalist and book reviewer. His most famous works include the early satires '' Decl ...

; and through his father's first cousin, Norah Emily Gorman Power, he was related to the theatrical director Sir (William) Tyrone Guthrie

Sir William Tyrone Guthrie (2 July 1900 – 15 May 1971) was an English theatrical director instrumental in the founding of the Stratford Festival of Canada, the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and the Tyrone Guthrie Centre at ...

, the first Director of the Stratford Festival

The Stratford Festival is a theatre festival which runs from April to October in the city of Stratford, Ontario, Canada. Founded by local journalist Tom Patterson in 1952, the festival was formerly known as the Stratford Shakespearean Festival ...

in Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

; and the Tyrone Guthrie Theatre

The Guthrie Theater, founded in 1963, is a center for theater performance, production, education, and professional training in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The concept of the theater was born in 1959 in a series of discussions between Sir Tyrone Gut ...

in Minneapolis, Minnesota

Minneapolis () is the largest city in Minnesota, United States, and the county seat of Hennepin County. The city is abundant in water, with thirteen lakes, wetlands, the Mississippi River, creeks and waterfalls. Minneapolis has its origi ...

.

Power went to Cincinnati-area Catholic schools and graduated from Purcell High School in 1931. Upon his graduation, he opted to join his father to learn what he could about acting from one of the stage's most respected actors.

Early career

1930s

Power joined his father for the summer of 1931, after being separated from him for some years due to his parents' divorce. His father suffered a heart attack in December 1931, dying in his son's arms, while preparing to perform in ''The Miracle Man''. Tyrone Power Jr., as he was then known, decided to continue pursuing an acting career. He tried to find work as an actor, and, while many contacts knew his father well, they offered praise for his father but no work for his son. He appeared in a bit part in 1932 in ''Tom Brown of Culver'', a movie starring actor Tom Brown. Power's experience in that movie did not open any other doors, however, and, except for what amounted to little more than a job as an extra in ''Flirtation Walk

''Flirtation Walk'' is a 1934 American romantic musical film written by Delmer Daves and Lou Edelman, and directed by Frank Borzage. It focuses on a soldier (Dick Powell) who falls in love with a general's daughter (Ruby Keeler) during the gene ...

'', he found himself frozen out of the movies but making some appearances in community theater. Discouraged, he took the advice of a friend, Arthur Caesar, to go to New York to gain experience as a stage actor. Among the Broadway plays in which he was cast are ''Flowers of the Forest'', '' Saint Joan'', and ''Romeo and Juliet''.

Power went to Hollywood in 1936. The director Henry King was impressed with his looks and poise, and he insisted that Power be tested for the lead role in ''Lloyd's of London

Lloyd's of London, generally known simply as Lloyd's, is an insurance and reinsurance market located in London, England. Unlike most of its competitors in the industry, it is not an insurance company; rather, Lloyd's is a corporate body gove ...

'', a role thought already to belong to Don Ameche

Don Ameche (; born Dominic Felix Amici; May 31, 1908 – December 6, 1993) was an American actor, comedian and vaudevillian. After playing in college shows, stock, and vaudeville, he became a major radio star in the early 1930s, which ...

. Despite his own reservations, Darryl F. Zanuck decided to give Power the role, once King and Fox film editor Barbara McLean convinced him that Power had a greater screen presence than Ameche. Power was billed fourth in the movie but he had by far the most screen time of any member of the cast. He walked into the premiere of the movie an unknown and he walked out a star, which he remained the rest of his career.

Power racked up hit after hit from 1936 until 1943, when his career was interrupted by military service. In these years he starred in romantic comedies such as '' Thin Ice'' and ''

Power racked up hit after hit from 1936 until 1943, when his career was interrupted by military service. In these years he starred in romantic comedies such as '' Thin Ice'' and ''Day-Time Wife

''Day-Time Wife'' is a 1939 comedy directed by Gregory Ratoff, starring Tyrone Power and Linda Darnell. Darnell and Power play Jane and Ken Norton, a married couple approaching their second anniversary. This was Linda Darnell's second film. ''Da ...

'', in dramas such as ''Suez

Suez ( ar, السويس '; ) is a seaport city (population of about 750,000 ) in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez (a branch of the Red Sea), near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal, having the same bou ...

'', '' Blood and Sand'', '' Son of Fury: The Story of Benjamin Blake'', ''The Rains Came

''The Rains Came'' is a 1939 20th Century Fox film based on an American novel by Louis Bromfield (published in June 1937 by Harper & Brothers). The film was directed by Clarence Brown and stars Myrna Loy, Tyrone Power, George Brent, Brenda ...

'' and ''In Old Chicago

''In Old Chicago'' is a 1938 American disaster musical drama film directed by Henry King. The screenplay by Sonya Levien and Lamar Trotti was based on the Niven Busch story, "We the O'Learys". The film is a fictionalized account about the G ...

''; in musicals ''Alexander's Ragtime Band

"Alexander's Ragtime Band" is a Tin Pan Alley song by American composer Irving Berlin released in 1911 and is often inaccurately cited as his first global hit. Despite its title, the song is a march as opposed to a rag and contains little sync ...

'', '' Second Fiddle'', and ''Rose of Washington Square

''Rose of Washington Square'' is a 1939 American musical drama film, featuring the already well-known popular song with the same title. Set in 1920s New York City, the film focuses on singer Rose Sargent and her turbulent relationship with con ar ...

''; in the westerns ''Jesse James

Jesse Woodson James (September 5, 1847April 3, 1882) was an American outlaw, bank and train robber, guerrilla and leader of the James–Younger Gang. Raised in the " Little Dixie" area of Western Missouri, James and his family maintained st ...

'' (1939) and ''Brigham Young

Brigham Young (; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American religious leader and politician. He was the second president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), from 1847 until his death in 1877. During his time as chu ...

''; in the war films '' A Yank in the R.A.F.'' and '' This Above All''; and the swashbucklers '' The Mark of Zorro'' and '' The Black Swan''. ''Jesse James'' was a very big hit at the box office, but it did receive some criticism for fictionalizing and glamorizing the famous outlaw. The movie was shot in and around Pineville, Missouri, and was Power's first location shoot and his first Technicolor

Technicolor is a series of Color motion picture film, color motion picture processes, the first version dating back to 1916, and followed by improved versions over several decades.

Definitive Technicolor movies using three black and white films ...

movie. (Before his career was over, he had filmed a total of 16 movies in color, including the movie he was filming when he died.) He was loaned out once, to MGM for ''Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette Josèphe Jeanne (; ; née Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last queen of France before the French Revolution. She was born an archduchess of Austria, and was the penultimate child a ...

'' (1938). Darryl F. Zanuck was angry that MGM used Fox's biggest star in what was, despite billing, a supporting role, and he vowed to never again loan him out, though Power's services were requested for the roles of Ashley Wilkes in '' Gone with the Wind'', Joe Bonaparte in '' Golden Boy'', and Parris in ''Kings Row

''Kings Row'' is a 1942 film starring Ann Sheridan, Robert Cummings, Ronald Reagan and Betty Field that tells a story of young people growing up in a small American town at the turn of the twentieth century. The picture was directed by Sam Wood ...

''; roles in several films produced by Harry Cohn

Harry Cohn (July 23, 1891 – February 27, 1958) was a co-founder, president, and production director of Columbia Pictures Corporation.

Life and career

Cohn was born to a working-class Jewish family in New York City. His father, Joseph Cohn, w ...

; and the role of Monroe Stahr in a planned production by Norma Shearer

Edith Norma Shearer (August 11, 1902June 12, 1983) was a Canadian-American actress who was active on film from 1919 through 1942. Shearer often played spunky, sexually liberated ingénues. She appeared in adaptations of Noël Coward, Eugene O' ...

of '' The Last Tycoon''.

Power was named the second biggest box-office draw in 1939, surpassed only by Mickey Rooney

Mickey Rooney (born Joseph Yule Jr.; other pseudonym Mickey Maguire; September 23, 1920 – April 6, 2014) was an American actor. In a career spanning nine decades, he appeared in more than 300 films and was among the last surviving stars of the ...

. His box office numbers are some of the best of all time.

1940–1943

In 1940, the direction of Power's career took a dramatic turn when his movie '' The Mark of Zorro'' was released. Power played the role of Don Diego Vega/Zorro, a fop by day, a bandit hero by night. The role had been performed by Douglas Fairbanks in the 1920 movie of the same title. The film was a hit, and 20th Century Fox often cast Power in other swashbucklers in the years that followed. Power was a talented swordsman in real life, and the dueling scene in ''The Mark of Zorro'' is highly regarded. The great Hollywood swordsman,

In 1940, the direction of Power's career took a dramatic turn when his movie '' The Mark of Zorro'' was released. Power played the role of Don Diego Vega/Zorro, a fop by day, a bandit hero by night. The role had been performed by Douglas Fairbanks in the 1920 movie of the same title. The film was a hit, and 20th Century Fox often cast Power in other swashbucklers in the years that followed. Power was a talented swordsman in real life, and the dueling scene in ''The Mark of Zorro'' is highly regarded. The great Hollywood swordsman, Basil Rathbone

Philip St. John Basil Rathbone MC (13 June 1892 – 21 July 1967) was a South African-born English actor. He rose to prominence in the United Kingdom as a Shakespearean stage actor and went on to appear in more than 70 films, primarily costume ...

, who starred with him in ''The Mark of Zorro'', commented, "Power was the most agile man with a sword I've ever faced before a camera. Tyrone could have fenced Errol Flynn

Errol Leslie Thomson Flynn (20 June 1909 – 14 October 1959) was an Australian-American actor who achieved worldwide fame during the Classical Hollywood cinema, Golden Age of Hollywood. He was known for his romantic swashbuckler roles, freque ...

into a cocked hat."

Power's career was interrupted in 1943 by military service. He reported to the United States Marine Corps

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for conducting expeditionary and amphibious operations through c ...

for training in late 1942, but was sent back, at the request of 20th Century-Fox, to complete one more film, ''Crash Dive

A crash dive is a maneuver by a submarine in which the vessel submerges as quickly as possible to avoid attack. Crash diving from the surface to avoid attack has been largely rendered obsolete with the advent of nuclear-powered submarines, as they ...

'', a patriotic war movie released in 1943. He was credited in the movie as Tyrone Power, U.S.M.C.R., and the movie served as a recruiting film.

Military service

In August 1942, Power enlisted in theUnited States Marine Corps

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for conducting expeditionary and amphibious operations through c ...

. He attended boot camp at Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego

Marine Corps Recruit Depot (commonly referred to as MCRD) San Diego is a United States Marine Corps military installation in San Diego, California. It lies between San Diego Bay and Interstate 5, adjacent to San Diego International Airport and th ...

, then Officer's Candidate School at Marine Corps Base Quantico

Marine Corps Base Quantico (commonly abbreviated MCB Quantico) is a United States Marine Corps installation located near Triangle, Virginia, covering nearly of southern Prince William County, Virginia, northern Stafford County, and southeas ...

, where he was commissioned a second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army unt ...

on June 2, 1943. As he had already logged 180 solo hours as a pilot before enlisting, he was able to do a short, intense flight training program at Naval Air Station Corpus Christi

Naval Air Station Corpus Christi is a United States Navy naval air base located six miles (10 km) southeast of the central business district (CBD) of Corpus Christi, in Nueces County, Texas.

History

A naval air station for Corpus Christi ...

, Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

. The pass earned him his wings and a promotion to first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a ...

. The Marine Corps considered Power over the age limit for active combat flying, so he volunteered for piloting cargo planes that he felt would get him into active combat zones.

In July 1944, Power was assigned to Marine Transport Squadron (VMR)-352 as a R5C (Navy version of Army Curtiss Commando C-46) transport co-pilot at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point

Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point or MCAS Cherry Point (*) is a United States Marine Corps airfield located in Havelock, North Carolina, United States, in the eastern part of the state. It was built in 1941, and was commissioned in 1942 and ...

, North Carolina

North Carolina () is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 28th largest and List of states and territories of the United ...

. The squadron moved to Marine Corps Air Station El Centro in California in December 1944. Power was later reassigned to VMR-353, joining them on Kwajalein Atoll

Kwajalein Atoll (; Marshallese: ) is part of the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI). The southernmost and largest island in the atoll is named Kwajalein Island, which its majority English-speaking residents (about 1,000 mostly U.S. civilia ...

in the Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands ( mh, Ṃajeḷ), officially the Republic of the Marshall Islands ( mh, Aolepān Aorōkin Ṃajeḷ),'' () is an independent island country and microstate near the Equator in the Pacific Ocean, slightly west of the Inte ...

in February 1945. From there, he flew missions carrying cargo in and wounded Marines out during the Battles of Iwo Jima (Feb-Mar 1945) and Okinawa (Apr-Jun 1945).

For his services in the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War, was the theater of World War II that was fought in Asia, the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and Oceania. It was geographically the largest theater of the war, including the vas ...

, Power was awarded the American Campaign Medal

The American Campaign Medal is a military award of the United States Armed Forces which was first created on November 6, 1942, by issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The medal was intended to recognize those military members who had perfo ...

, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with two bronze stars, and the World War II Victory Medal

The World War II Victory Medal is a service medal of the United States military which was established by an Act of Congress on 6 July 1945 (Public Law 135, 79th Congress) and promulgated by Section V, War Department Bulletin 12, 1945.

The Wo ...

.

Power returned to the United States in November 1945 and was released from active duty in January 1946. He was promoted to the rank of captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

in the reserves on May 8, 1951. He remained in the reserves the rest of his life and reached the rank of major in 1957.''Los Angeles Times'', March 30, 2003 p. 193

In the June 2001 ''Marine Air Transporter'' newsletter, Jerry Taylor, a retired Marine Corps flight instructor, recalled training Power as a Marine pilot, saying, "He was an excellent student, never forgot a procedure I showed him or anything I told him." Others who served with him have also commented on how well Power was respected by those with whom he served.

Following the war, 20th Century Fox provided Power with a surplus DC-3 that he named ''The Geek'' that he frequently piloted.

When Power died suddenly at age 44, he was buried with full military honors.

Post-war career

Late 1940s

Other than re-releases of his films, Power was not seen on screen again after his entry into the Marines until 1946, when he co-starred with Gene Tierney, John Payne and

Other than re-releases of his films, Power was not seen on screen again after his entry into the Marines until 1946, when he co-starred with Gene Tierney, John Payne and Anne Baxter

Anne Baxter (May 7, 1923 – December 12, 1985) was an American actress, star of Hollywood films, Broadway productions, and television series. She won an Academy Award and a Golden Globe, and was nominated for an Emmy.

A granddaughter of Fr ...

in ''The Razor's Edge

''The Razor's Edge'' is a 1944 novel by W. Somerset Maugham. It tells the story of Larry Darrell, an American pilot traumatized by his experiences in World War I, who sets off in search of some transcendent meaning in his life. The story b ...

'', an adaptation of W. Somerset Maugham

William Somerset Maugham ( ; 25 January 1874 – 16 December 1965) was an English writer, known for his plays, novels and short stories. Born in Paris, where he spent his first ten years, Maugham was schooled in England and went to a German un ...

's novel

A novel is a relatively long work of narrative fiction, typically written in prose and published as a book. The present English word for a long work of prose fiction derives from the for "new", "news", or "short story of something new", itself ...

of the same title.

Next up for release was a movie that Power had to fight hard to make, the film noir

Film noir (; ) is a cinematic term used primarily to describe stylish Hollywood crime dramas, particularly those that emphasize cynical attitudes and motivations. The 1940s and 1950s are generally regarded as the "classic period" of American '' ...

'' Nightmare Alley'' (1947). Darryl F. Zanuck was reluctant for Power to make the movie because his handsome appearance and charming manner had been marketable assets for the studio for many years. Zanuck feared that the dark role might damage Power's image. Zanuck eventually agreed, giving Power A-list production values for what normally would be a B film. The movie was directed by Edmund Goulding

Edmund Goulding (20 March 1891 – 24 December 1959) was a British screenwriter and film director. As an actor early in his career he was one of the 'Ghosts' in the 1922 silent film '' Three Live Ghosts'' alongside Norman Kerry and Cyril Chadwi ...

, and though it was a failure at the box-office, it was one of Power's favorite roles for which he received some of the best reviews of his career. However, Zanuck continued to disapprove of his "darling boy" being seen in such a film with a downward spiral. So, he did not publicize it and removed it from release after only a few weeks insisting that it was a flop. The film was released on DVD in 2005 after years of legal issues.

Zanuck quickly released another costume-clad movie, '' Captain from Castile'' (also 1947), directed by Henry King, who directed Power in eleven movies. After making a couple of light romantic comedies reuniting him with two actresses under contract to 20th Century Fox, ''That Wonderful Urge

''That Wonderful Urge'' is a 1948 20th Century Fox screwball comedy film directed by Robert B. Sinclair and starring Tyrone Power and Gene Tierney.''Harrison's Reports'' film review; November 27, 1948, page 190. It is a remake of '' Love Is News ...

'' with Gene Tierney and '' The Luck of the Irish'' (both 1948) with Anne Baxter. After these films, Power once again found himself in two swashbucklers, ''Prince of Foxes

''Prince of Foxes'' is a 1947 historical novel by Samuel Shellabarger, following the adventures of the fictional Andrea Orsini, a captain in the service of Cesare Borgia during his conquest of the Romagna.

Plot introduction

Andrea Zoppo, an Ita ...

'' (1949) and '' The Black Rose'' (1950).

1950s

Power was becoming increasingly dissatisfied with his costume roles, and he struggled between being a star and becoming a great actor. He was forced to take on assignments he found unappealing, such movies as '' American Guerrilla in the Philippines'' (1950) and ''Pony Soldier

''Pony Soldier'' is a 1952 American Northern Western film set in Canada, but filmed in Sedona, Arizona. It is based on a 1951 ''Saturday Evening Post'' story "Mounted Patrol" by Garnett Weston. It was retitled ''MacDonald of the Canadian Mount ...

'' (1952). In 1950, he traveled to England to play the title role in '' Mister Roberts'' on stage at the London Coliseum

The London Coliseum (also known as the Coliseum Theatre) is a theatre in St Martin's Lane, Westminster, built as one of London's largest and most luxurious "family" variety theatres. Opened on 24 December 1904 as the London Coliseum Theatre ...

, bringing in sellout crowds for twenty-three weeks.

Protesting being cast in one costume film after another, Power refused to star in ''Lydia Bailey

''Lydia Bailey'' is a 1952 American historical film directed by Jean Negulesco, based on the novel of the same name by Kenneth Roberts. It stars Dale Robertson and Anne Francis.

Plot

In 1802, lawyer Albion Hamlin travels from Baltimore to Cap ...

'' with his role going to Dale Robertson; Power was placed under suspension. Power next appeared in ''Diplomatic Courier

A diplomatic courier is an official who transports diplomatic bags as sanctioned under the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations. Couriers are granted diplomatic immunity and are thereby protected by the receiving state from arrest and d ...

'' (1952), a cold war

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

spy drama directed by Henry Hathaway

Henry Hathaway (March 13, 1898 – February 11, 1985) was an American film director and producer. He is best known as a director of Westerns, especially starring Randolph Scott and John Wayne. He directed Gary Cooper in seven films.

Backgrou ...

which received very modest reviews. It took its place among several other American spy movies, released previously, with similar material.

Power's movies had been highly profitable for Fox in the past, and as an enticement to renew his contract a third time, Fox offered him the lead role in '' The Robe'' (1953). He turned it down (Richard Burton

Richard Burton (; born Richard Walter Jenkins Jr.; 10 November 1925 – 5 August 1984) was a Welsh actor. Noted for his baritone voice, Burton established himself as a formidable Shakespearean actor in the 1950s, and he gave a memorable pe ...

was cast instead) and on 1 November 1952, he left on a ten-week national tour with ''John Brown's Body

"John Brown's Body" (originally known as "John Brown's Song") is a United States marching song about the abolitionist John Brown. The song was popular in the Union during the American Civil War. The tune arose out of the folk hymn tradition o ...

'', a three-person dramatic reading of Stephen Vincent Benét

Stephen Vincent Benét (; July 22, 1898 – March 13, 1943) was an American poet, short story writer, and novelist. He is best known for his book-length narrative poem of the American Civil War, '' John Brown's Body'' (1928), for which he receiv ...

's narrative poem, adapted and directed by Charles Laughton

Charles Laughton (1 July 1899 – 15 December 1962) was a British actor. He was trained in London at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and first appeared professionally on the stage in 1926. In 1927, he was cast in a play with his future ...

, featuring Power, Judith Anderson and Raymond Massey

Raymond Hart Massey (August 30, 1896 – July 29, 1983) was a Canadian actor, known for his commanding, stage-trained voice. For his lead role in '' Abe Lincoln in Illinois'' (1940), Massey was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor. Amo ...

. The tour culminated in a run of 65 shows between February and April 1953 at the New Century Theatre

The New Century Theatre was a Broadway theater in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City, at 205–207 West 58th Street and 926–932 Seventh Avenue. Opened on October 6, 1921, as Jolson's 59th Street Theatre, the theater was desig ...

on Broadway. A second national tour with the show began in October 1953, this time for four months, and with Raymond Massey and Anne Baxter. In the same year, Power filmed ''King of The Khyber Rifles

''King of the Khyber Rifles'' is a novel by British writer Talbot Mundy. Captain Athelstan King is a secret agent for the British Raj at the beginning of the First World War. Heavily influenced both by Mundy's own unsuccessful career in India ...

'', a depiction of India in 1857, with Terry Moore and Michael Rennie

Michael Rennie (born Eric Alexander Rennie; 25 August 1909 – 10 June 1971) was a British film, television and stage actor, who had leading roles in a number of Hollywood films, including his portrayal of the space visitor Klaatu in the s ...

.

Fox now gave Power permission to seek his own roles outside the studio, on the understanding that he would fulfill his fourteen-film commitment to them in between his other projects. He made '' The Mississippi Gambler'' (1953) for Universal-International, negotiating a deal entitling him to a percentage of the profits. He earned a million dollars from the movie. Also in 1953, actress and producer Katharine Cornell

Katharine Cornell (February 16, 1893June 9, 1974) was an American stage actress, writer, theater owner and producer. She was born in Berlin to American parents and raised in Buffalo, New York.

Dubbed "The First Lady of the Theatre" by critic A ...

cast Power as her love interest in the play '' The Dark is Light Enough'', a verse drama by British dramatist Christopher Fry

Christopher Fry (18 December 1907 – 30 June 2005) was an English poet and playwright. He is best known for his verse dramas, especially '' The Lady's Not for Burning'', which made him a major force in theatre in the 1940s and 1950s.

Biograp ...

set in Austria in 1848. Between November 1954 and April 1955, Power toured the United States and Canada in the role, ending with 12 weeks at the ANTA Theater, New York, and two weeks at the Colonial Theater, Boston. His performance in Julian Claman's ''A Quiet Place'', staged at the National Theater, Washington, at the end of 1955 was warmly received by the critics.

'' Untamed'' (1955) was Tyrone Power's last movie made under his contract with 20th Century-Fox. The same year saw the release of ''

'' Untamed'' (1955) was Tyrone Power's last movie made under his contract with 20th Century-Fox. The same year saw the release of ''The Long Gray Line

''The Long Gray Line'' is a 1955 American Cinemascope Technicolor biographical comedy-drama film in CinemaScope directed by John Ford based on the life of Marty Maher and his autobiography, Bringing Up the Brass'' co-written witNardi Reeder Cam ...

'', a John Ford

John Martin Feeney (February 1, 1894 – August 31, 1973), known professionally as John Ford, was an American film director and naval officer. He is widely regarded as one of the most important and influential filmmakers of his generation. He ...

film for Columbia Pictures

Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. is an American film production studio that is a member of the Sony Pictures Motion Picture Group, a division of Sony Pictures Entertainment, which is one of the Big Five studios and a subsidiary of the mu ...

. In 1956, the year Columbia released ''The Eddy Duchin Story

''The Eddy Duchin Story'' is a 1956 Technicolor film biopic of band leader and pianist Eddy Duchin. It was directed by George Sidney, written by Samuel A. Taylor, and starred Tyrone Power and Kim Novak. Harry Stradling received an Academy Award ...

'', another great success for the star, he returned to England to play the rake Dick Dudgeon in a revival of Shaw

Shaw may refer to:

Places Australia

*Shaw, Queensland

Canada

* Shaw Street, a street in Toronto

England

*Shaw, Berkshire, a village

* Shaw, Greater Manchester, a location in the parish of Shaw and Crompton

* Shaw, Swindon, a suburb of Swindon

...

's '' The Devil's Disciple'' for one week at the Opera House

An opera house is a theatre building used for performances of opera. It usually includes a stage, an orchestra pit, audience seating, and backstage facilities for costumes and building sets.

While some venues are constructed specifically fo ...

in Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The ...

, and nineteen weeks at the Winter Garden, London.

Darryl F. Zanuck, persuaded him to play the lead role in ''The Sun Also Rises

''The Sun Also Rises'' is a 1926 novel by American writer Ernest Hemingway, his first, that portrays American and British expatriates who travel from Paris to the Festival of San Fermín in Pamplona to watch the running of the bulls and the bu ...

'' (1957), adapted from the Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. His economical and understated style—which he termed the iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century fi ...

novel, with Ava Gardner

Ava Lavinia Gardner (December 24, 1922 – January 25, 1990) was an American actress. She first signed a contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in 1941 and appeared mainly in small roles until she drew critics' attention in 1946 with her perform ...

and Errol Flynn. This was his final film with Fox. Released that same year were ''Seven Waves Away

''Seven Waves Away'' (alternate U.S. titles: ''Abandon Ship!'' and ''Seven Days From Now'') is a 1957 British adventure film directed by Richard Sale and starring Tyrone Power, Mai Zetterling, Lloyd Nolan, and Stephen Boyd. When his ship goes ...

'' (US: ''Abandon Ship!''), shot in Great Britain, and John Ford's '' Rising of the Moon'' (narrator only), which was filmed in Ireland, both for Copa Productions.

For Power's last completed film role he was cast against type as the accused murderer Leonard Vole in the first film version of Agatha Christie

Dame Agatha Mary Clarissa Christie, Lady Mallowan, (; 15 September 1890 – 12 January 1976) was an English writer known for her 66 detective novels and 14 short story collections, particularly those revolving around fiction ...

's ''Witness for the Prosecution

In law, a witness is someone who has knowledge about a matter, whether they have sensed it or are testifying on another witnesses' behalf. In law a witness is someone who, either voluntarily or under compulsion, provides testimonial evidence, e ...

'' (1957), directed by Billy Wilder

Billy Wilder (; ; born Samuel Wilder; June 22, 1906 – March 27, 2002) was an Austrian-American filmmaker. His career in Hollywood spanned five decades, and he is regarded as one of the most brilliant and versatile filmmakers of Classic Holly ...

. The film was a critically well-received box-office success. Writing for the ''National Post

The ''National Post'' is a Canadian English-language broadsheet newspaper available in several cities in central and western Canada. The paper is the flagship publication of Postmedia Network and is published Mondays through Saturdays, with ...

'' in 2002, Robert Fulford commented on Power's "superb performance" as "the seedy, stop-at-nothing exploiter of women". Power returned to the stage in March 1958, to play the lead in Arnold Moss

Arnold Moss (January 28, 1910 – December 15, 1989) was an American character actor. His son was songwriter Jeff Moss.

Early years

Born in Flatbush, Moss was a third-generation Brooklyn native. He attended Brooklyn's Boys High School. ...

's adaptation of Shaw

Shaw may refer to:

Places Australia

*Shaw, Queensland

Canada

* Shaw Street, a street in Toronto

England

*Shaw, Berkshire, a village

* Shaw, Greater Manchester, a location in the parish of Shaw and Crompton

* Shaw, Swindon, a suburb of Swindon

...

's 1921 play, ''Back to Methuselah

''Back to Methuselah (A Metabiological Pentateuch)'' by George Bernard Shaw consists of a preface (''The Infidel Half Century'') and a series of five plays: ''In the Beginning: B.C. 4004 (In the Garden of Eden)'', ''The Gospel of the Brothers Bar ...

''.

Personal life

Power was one of Hollywood's most eligible bachelors until he married French actress Annabella (born Suzanne Georgette Charpentier) on July 14, 1939. They had met on the 20th Century Fox lot around the time they starred together in the movie ''Suez''. Power adopted Annabella's daughter, Anne, before leaving for service. In an

Power was one of Hollywood's most eligible bachelors until he married French actress Annabella (born Suzanne Georgette Charpentier) on July 14, 1939. They had met on the 20th Century Fox lot around the time they starred together in the movie ''Suez''. Power adopted Annabella's daughter, Anne, before leaving for service. In an A&E biography

''Biography'' is an American documentary television series and media franchise created in the 1960s by David L. Wolper and owned by A&E Networks since 1987. Each episode depicts the life of a notable person with narration, on-camera interview ...

, Annabella said that Zanuck "could not stop Tyrone's love for me, or my love for Tyrone." J. Watson Webb, close friend and an editor at 20th Century Fox, maintained in the ''A&E Biography'' that one of the reasons the marriage fell apart was Annabella's inability to give Power a son, yet, Webb said, there was no bitterness between the couple. In a March 1947 issue of ''Photoplay'', Power was interviewed and said that he wanted a home and children, especially a son to carry on his acting legacy. Annabella shed some light on the situation in an interview published in ''Movieland'' magazine in 1948. She said, "Our troubles began because the war started earlier for me, a French-born woman, than it did for Americans." She explained that the war clouds over Europe made her unhappy and irritable, and to get her mind off her troubles, she began accepting stage work, which often took her away from home. "It is always difficult to put one's finger exactly on the place and time where a marriage starts to break up," she said "but I think it began then. We were terribly sad about it, both of us, but we knew we were drifting apart. I didn't think then—and I don't think now—that it was his fault, or mine." The couple tried to make their marriage work when Power returned from military service, but they were unable to do so.

Following his separation from Annabella, Power entered into a love affair with Lana Turner

Lana Turner ( ; born Julia Jean Turner; February 8, 1921June 29, 1995) was an American actress. Over the course of her nearly 50-year career, she achieved fame as both a pin-up model and a film actress, as well as for her highly publicized pe ...

that lasted for a couple of years. In her 1982 autobiography, Turner claimed that she became pregnant with Power's child in 1948, but chose to have an abortion.

In 1946, Power and lifelong friend Cesar Romero

Cesar Julio Romero Jr. (February 15, 1907 – January 1, 1994) was an American actor and activist. He was active in film, radio, and television for almost sixty years.

His wide range of screen roles included Latin lovers, historical figures in c ...

, accompanied by former flight instructor and war veteran John Jefferies as navigator

A navigator is the person on board a ship or aircraft responsible for its navigation.Grierson, MikeAviation History—Demise of the Flight Navigator FrancoFlyers.org website, October 14, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2014. The navigator's prima ...

, embarked on a goodwill tour throughout South America where they met, among others, Juan

''Juan'' is a given name, the Spanish and Manx versions of ''John''. It is very common in Spain and in other Spanish-speaking communities around the world and in the Philippines, and also (pronounced differently) in the Isle of Man. In Spanish, ...

and Evita Peron in Argentina. On September 1, 1947, Power set out on another goodwill trip around the world, piloting his own plane, "The Geek". He flew with Bob Buck, another experienced pilot and war veteran. Buck stated in his autobiography that Power had a photographic mind, was an excellent pilot, and genuinely liked people. They flew with a crew to various locations in Europe and South Africa, often mobbed by fans when they hit the ground. However, in 1948 when "The Geek" reached Rome, Power met and fell in love with Mexican actress Linda Christian. Turner claimed that the story of her dining out with Power's friend Frank Sinatra

Francis Albert Sinatra (; December 12, 1915 – May 14, 1998) was an American singer and actor. Nicknamed the " Chairman of the Board" and later called "Ol' Blue Eyes", Sinatra was one of the most popular entertainers of the 1940s, 1950s, and ...

was leaked to Power and that Power became very upset that she was "dating" another man in his absence. Turner also claimed that it could not have been a coincidence that Linda Christian was at the same hotel as Tyrone Power and implied that Christian had obtained Power's itinerary from 20th Century Fox.

Power and Christian were married on January 27, 1949, in the Church of Santa Francesca Romana

Santa Francesca Romana ( it, Basilica di Santa Francesca Romana), previously known as Santa Maria Nova, is a Roman Catholic church situated next to the Roman Forum in the rione Campitelli in Rome, Italy.

History

An oratory putatively was est ...

, with an estimated 8,000 to 10,000 screaming fans outside. Christian miscarried three times before giving birth to a baby girl, Romina Francesca Power, on October 2, 1951. A second daughter, Taryn Stephanie Power, was born on September 13, 1953. Around the time of Taryn's birth, the marriage was becoming rocky. In her autobiography, Christian blamed the breakup of her marriage on her husband's extramarital affairs, but acknowledged that she had had an affair with Edmund Purdom, which created great tension between Christian and her husband. They divorced in 1955.

After his divorce from Christian, Power had a long-lasting love affair with Mai Zetterling

Mai Elisabeth Zetterling (; 24 May 1925 – 17 March 1994) was a Swedish film director, novelist and actor.

Early life

Zetterling was born in Västerås, Sweden to a working class family. She started her career as an actor at the age of 17 at ...

, whom he had met on the set of ''Abandon Ship!

''Seven Waves Away'' (alternate U.S. titles: ''Abandon Ship!'' and ''Seven Days From Now'') is a 1957 British adventure film directed by Richard Sale and starring Tyrone Power, Mai Zetterling, Lloyd Nolan, and Stephen Boyd. When his ship goe ...

''. At the time, he vowed that he would never marry again, because he had been twice burned financially by his previous marriages. He also entered into an affair with a British actress, Thelma Ruby. However, in 1957, he met the former Deborah Jean Smith (sometimes incorrectly referred to as Deborah Ann Montgomery), who went by her former married name, Debbie Minardos. They were married on May 7, 1958, and she became pregnant

Pregnancy is the time during which one or more offspring develops ( gestates) inside a woman's uterus (womb). A multiple pregnancy involves more than one offspring, such as with twins.

Pregnancy usually occurs by sexual intercourse, but ca ...

soon after with Tyrone Power Jr., the son he had always wanted.

Death

In September 1958, Power and his wife Deborah traveled toMadrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

and Valdespartera, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

to film the epic '' Solomon and Sheba,'' directed by King Vidor

King Wallis Vidor (; February 8, 1894 – November 1, 1982) was an American film director, film producer, and screenwriter whose 67-year film-making career successfully spanned the silent and sound eras. His works are distinguished by a vivid, ...

and costarring Gina Lollobrigida

Luigia "Gina" Lollobrigida (born 4 July 1927) is an Italian actress, photojournalist, and politician. She was one of the highest-profile European actresses of the 1950s and early 1960s, a period in which she was an international sex symbol. As o ...

. Probably affected by hereditary heart disease, and a chain smoker who smoked three to four packs a day, Power had filmed about 75% of his scenes when he was stricken by a massive heart attack while filming a dueling scene with his frequent costar and friend George Sanders

George Henry Sanders (3 July 1906 – 25 April 1972) was a British actor and singer whose career spanned over 40 years. His heavy, upper-class English accent and smooth, bass voice often led him to be cast as sophisticated but villainous chara ...

. A doctor diagnosed the cause of Power's death as "fulminant angina pectoris

Angina, also known as angina pectoris, is chest pain or pressure, usually caused by insufficient blood flow to the heart muscle (myocardium). It is most commonly a symptom of coronary artery disease.

Angina is typically the result of obstru ...

." Power died while being transported to the hospital in Madrid on November 15,

Hollywood Forever Cemetery

Hollywood Forever Cemetery is a full-service cemetery, funeral home, crematory, and cultural events center which regularly hosts community events such as live music and summer movie screenings. It is one of the oldest cemeteries in Los Angel ...

(then known as Hollywood Cemetery) in a military service on Henry King flew over the service; almost 20 years before, Power had flown in King's plane to the set of ''Jesse James

Jesse Woodson James (September 5, 1847April 3, 1882) was an American outlaw, bank and train robber, guerrilla and leader of the James–Younger Gang. Raised in the " Little Dixie" area of Western Missouri, James and his family maintained st ...

'' in Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

, Power's first experience with flying. Aviation became an important part of Power's life, both in the U.S. Marines and as a civilian. In the foreword to Dennis Belafonte's ''The Films of Tyrone Power,'' King wrote: "Knowing his love for flying and feeling that I had started it, I flew over his funeral procession and memorial park during his burial, and felt that he was with me."

Power was interred beside a small lake. His grave is marked with a gravestone in the form of a marble bench containing the masks of comedy and tragedy with the inscription "Good night, sweet prince." At Power's grave, Laurence Olivier

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier (; 22 May 1907 – 11 July 1989) was an English actor and director who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud, was one of a trio of male actors who dominated the British stage ...

read the poem " High Flight."

Power's will, filed on December 8, 1958, contained a then-unusual provision that his eyes be donated to the Estelle Doheny Eye Foundation for corneal transplantation

Corneal transplantation, also known as corneal grafting, is a surgical procedure where a damaged or diseased cornea is replaced by donated corneal tissue (the graft). When the entire cornea is replaced it is known as penetrating keratoplasty a ...

or retinal

Retinal (also known as retinaldehyde) is a polyene chromophore. Retinal, bound to proteins called opsins, is the chemical basis of visual phototransduction, the light-detection stage of visual perception (vision).

Some microorganisms use reti ...

study.

Deborah Power gave birth to a son on January 22, 1959, two months after her husband's death. She remarried within the year to producer Arthur Loew Jr.

Honors

For Power's contribution to motion pictures, he was honored in 1960 with a star on theHollywood Walk of Fame

The Hollywood Walk of Fame is a historic landmark which consists of more than 2,700 five-pointed terrazzo and brass stars embedded in the sidewalks along 15 blocks of Hollywood Boulevard and three blocks of Vine Street in Hollywood, Calif ...

that can be found at 6747 Hollywood Blvd. On the 50th anniversary of his death, Power was honored by American Cinematheque

The American Cinematheque is an independent, nonprofit cultural organization in Los Angeles, California, United States dedicated exclusively to the public presentation of the moving image in all its forms.

The Cinematheque was created in 1981 as ...

with a weekend of films and remembrances by co-stars and family as well as a memorabilia display at the Egyptian Theatre in Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world ...

from November 14–16, 2008. Also on display were the two known surviving panels from a large painted glass mural which Power and his wife had commissioned for their home, celebrating highlights of their lives and special moments in Tyrone's career, The December 2, 1952 issue of Look Magazine had also featured this mural in a four-page spread titled "The Tyrone Powers Pose For Their Portraits."

Power is shown on the cover of The Beatles

The Beatles were an English Rock music, rock band, formed in Liverpool in 1960, that comprised John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. They are regarded as the Cultural impact of the Beatles, most influential band of al ...

' album ''Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band

''Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band'' is the eighth studio album by the English rock band the Beatles. Released on 26May 1967, ''Sgt. Pepper'' is regarded by musicologists as an early concept album that advanced the roles of sound composi ...

'' in the third row. In 2018, Tyrone Power was ranked the 21st most popular male film star in history.

Filmography

Stage appearances

* ''Low and Behold'',

* ''Low and Behold'', Pasadena Playhouse

The Pasadena Playhouse is a historic performing arts venue located 39 S. El Molino Avenue in Pasadena, California, United States. The 686-seat auditorium produces a variety of cultural and artistic events, professional shows, and community engage ...

and Hollywood Music Box Theatre, CA (1933)

* ''Flowers of the Forest'', Martin Beck Theatre

The Al Hirschfeld Theatre, originally the Martin Beck Theatre, is a Broadway theater at 302 West 45th Street in the Theater District of Midtown Manhattan in New York City. Opened in 1924, it was designed by G. Albert Lansburgh in a Moorish a ...

, NY (1935-1936)

* ''Romeo and Juliet

''Romeo and Juliet'' is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare early in his career about the romance between two Italian youths from feuding families. It was among Shakespeare's most popular plays during his lifetime and, along with ''Ham ...

'', Martin Beck Theatre, NY (1935)

* '' Saint Joan'', Martin Beck Theatre, NY (1936)

* ''Liliom'', The Country Playhouse, Westport CT (1941* '' Mister Roberts'', London Coliseum, England (195

http://tyforum.bravepages.com/ta/ta-mr.html] * ''John Brown's Body'', Broadway Century Theatre, NY (1952–1953) * ''The Dark is Light Enough'' (1955) * ''A Quiet Place'', The Playwrights Co. (1955–1956) * ''The Devil's Disciple'', Winter Garden Theatre, London, England (1956) * ''Back to Methuselah'', Ambassador Theatre (New York City), Ambassador Theatre, NY (1958)

Radio appearances

References

External links

* * * * *Tyrone Power, King of 20th Century-Fox

*

Tyrone Power's newsreel appearances at the Associated Press Archive

Tyrone Power

at Virtual History {{DEFAULTSORT:Power, Tyrone 1914 births 1958 deaths Military personnel from Ohio 20th-century American male actors 20th Century Studios contract players American male film actors American male radio actors United States Marine Corps personnel of World War II American people of English descent American people of French-Canadian descent American people of German descent American people of Irish descent Burials at Hollywood Forever Cemetery Male actors from Cincinnati Power family United States Marine Corps officers United States Marine Corps reservists United States Marine Corps pilots of World War II LGBT male actors American LGBT actors Filmed deaths of entertainers