The history of the

Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

in

Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

extended nearly two thousand years and goes back to the

Punic era. The Jewish community in Tunisia is no doubt older and grew up following successive waves of immigration and proselytism before its development was hampered by anti-Jewish measures in the

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

. The community formerly used

its own dialect of Arabic. After the

Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

conquest of

Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

, Tunisian

Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in th ...

went through periods of relative freedom or even cultural apogee to times of more marked discrimination. The arrival of

Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

expelled from the

Iberian peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

, often through

Livorno

Livorno () is a port city on the Ligurian Sea on the western coast of Tuscany, Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Livorno, having a population of 158,493 residents in December 2017. It is traditionally known in English as Leghorn (pronou ...

, greatly altered the country. Its economic, social and cultural situation has improved markedly with the advent of the

French protectorate before being compromised during the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, with the occupation of the country by the

Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

. The creation of

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

in 1948 provoked a widespread

anti-Zionist

Anti-Zionism is opposition to Zionism. Although anti-Zionism is a heterogeneous phenomenon, all its proponents agree that the creation of the modern State of Israel, and the movement to create a sovereign Jewish state in the region of Palesti ...

reaction in the

Arab world

The Arab world ( ar, اَلْعَالَمُ الْعَرَبِيُّ '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, refers to a vast group of countries, mainly located in Western A ...

, to which was added nationalist agitation, nationalization of enterprises, Arabization of education and part of the administration. Jews left Tunisia en masse from the 1950s onwards because of the problems raised and the hostile climate created by the

Bizerte crisis

The Bizerte crisis (; ) occurred in July 1961 when Tunisia imposed a blockade on the French naval base at Bizerte, Tunisia, hoping to force its evacuation. The crisis culminated in a three-day battle between French and Tunisian forces that ...

in 1961 and the

Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab states (primarily Egypt, Syria, and Jordan) from 5 to 10 ...

in 1967. The Jewish population of Tunisia, estimated at about 105,000 individuals in 1948, numbered around 1,000 individuals as of 2019. These Jews lived mainly in Tunis, with communities present in

Djerba

Djerba (; ar, جربة, Jirba, ; it, Meninge, Girba), also transliterated as Jerba or Jarbah, is a Tunisian island and the largest island of North Africa at , in the Gulf of Gabès, off the coast of Tunisia. It had a population of 139,544 ...

.

The Jewish diaspora of Tunisia is divided between

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

and France,

where it has preserved its community identity through its traditions, mostly dependent on

Sephardic Judaism

Sephardic law and customs are the practice of Judaism by the Sephardim, the descendants of the historic Jewish community of the Iberian Peninsula. Some definitions of "Sephardic" inaccurately include Mizrahi Jews, many of whom follow the same ...

, but retaining its own specific characteristics. Djerbian Judaism in particular, considered to be more faithful to tradition because it remained outside the sphere of influence of the modernist currents, plays a dominant role. The vast majority of Tunisian Jews have

relocated to Israel and have

switched Switched may refer to:

* Switched (band)

Switched (previously depicted as Sw1tched) was a nu metal band from Cleveland, Ohio.

History

Forming in 1999 as Sw1tch, the band played shows around Ohio and released a demo entitled ''Fuckin' Demo''. T ...

to using Hebrew as their

home language

A first language, native tongue, native language, mother tongue or L1 is the first language or dialect that a person has been exposed to from birth or within the critical period. In some countries, the term ''native language'' or ''mother tongu ...

.

Tunisian Jews living in France typically use French as their first language, while the few still left in Tunisia tend to use either French or

Judeo-Tunisian Arabic

Judeo-Tunisian Arabic, also known as Judeo-Tunisian, is a variety of Tunisian Arabic mainly spoken by Jews living or formerly living in Tunisia. Speakers are older adults, and the younger generation has only a passive knowledge of the language. ...

in their everyday lives.

Historiography

The history of the Jews of Tunisia (until the establishment of the French protectorate) was first studied by

David Cazès David Cazès (born 1851, Tétouan, Morocco, died 1913) was a Moroccan Jewish educator and writer.

Early life

Sent to Paris in his early youth, he was educated by the Alliance Israélite Universelle, and at the age of eighteen was commissioned to e ...

in 1888 in his Essay on the History of the Israelites of Tunisia;

André Chouraqui

Nathan André Chouraqui (; 11 August 1917 – 9 July 2007) was a French- Algerian-Israeli lawyer, writer, scholar and politician.

Early life

Chouraqui was born in Aïn Témouchent, Algeria. His parents, Isaac Chouraqui and Meleha Meyer, both de ...

(1952) and later by Haim Zeev Hirschberg(1965), in the more general context of North African

Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in th ...

.

[Paul Sebag, ''Histoire des Juifs de Tunisie : des origines à nos jours'', éd. L’Harmattan, Paris, 1991, ] The research on the subject was then enriched by Robert Attal and Yitzhak Avrahami. In addition, various institutions, including the

Israel Folktale Archives in University of Haifa, the

Hebrew University of Jerusalem

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HUJI; he, הַאוּנִיבֶרְסִיטָה הַעִבְרִית בִּירוּשָׁלַיִם) is a public research university based in Jerusalem, Israel. Co-founded by Albert Einstein and Dr. Chaim Weiz ...

and the

Ben Zvi Institute

Yad Ben Zvi ( he, יד יצחק בן-צבי), also known as the Ben-Zvi Institute, is a research institute and publishing house named for Israeli president Yitzhak Ben-Zvi in Jerusalem.

History

Yad Ben-Zvi is a research institute established t ...

, collect material evidence (traditional clothing, embroidery, Lace, jewelry, etc.), traditions (folk tales, liturgical songs, etc.) and manuscripts as well as Judeo-Arabic books and newspapers.

Paul Sebag is the first to provide in his History of the Jews of Tunisia: from origins to our days (1991) a first development entirely devoted to the history of this community. In Tunisia, following the thesis of Abdelkrim Allagui, a group under the direction of Habib Kazdaghli and Abdelhamid Largueche brings the subject into the field of national academic research. Founded in Paris on June 3, 1997, the Society of Jewish History of Tunisia contributes to the research on the Jews of Tunisia and transmits their history through conferences, symposia and exhibitions.

According to

Michel Abitbol

Michel Abitbol ( he, מיכאל אביטבול; born 14 April 1943 in Casablanca, Morocco) is a Moroccan-Israeli historian.

He is considered an expert on the history of Morocco and the history the Jews of North Africa. In the 80s, he gave cour ...

, the study of Judaism in Tunisia has grown rapidly during the progressive dissolution of the Jewish community in the context of decolonization and the evolution of the Arab-Israeli conflict while Habib Kazdaghli believes that the departure of the Jewish community is the cause of the low number of studies related to the topic. Kazdaghli, however, points out that their production increases since the 1990s, due to the authors attached to this community, and that the associations of Jews originating from one or another community (Ariana, Bizerte, etc.) or Tunisia multiply. As for the fate of the Jewish community during the period of the German occupation of Tunisia (1942–1943), it remains relatively uncommon, and the Symposium on the Jewish Community of Tunisia held at the University of La Manouba in February 1998 (the first of its kind on this research theme) does not mention it. However, the work of memory of the community exists, with the testimonies of Robert Borgel and Paul Ghez, the novels "The Statue of Salt" by

Albert Memmi

Albert Memmi ( ar, ألبير ممّي; 15 December 1920 – 22 May 2020) was a French-Tunisian writer and essayist of Tunisian-Jewish origins.

Biography

Memmi was born in Tunis, French Tunisia in December 1920, to a Tunisian Jewish Berb ...

and Villa Jasmin by

Serge Moati

Serge Moati (born Henry Moati; 17 August 1946) is a French journalist, television presenter, film director and writer. He is the brother of Nine Moati, author of the novel ''Les Belles de Tunis''. As is his sister, Serge Moati is a French citize ...

as well as the works of some historians.

Antiquity

Hypothetical origins

Like many Jewish populations, such as in

Tripolitania

Tripolitania ( ar, طرابلس '; ber, Ṭrables, script=Latn; from Vulgar Latin: , from la, Regio Tripolitana, from grc-gre, Τριπολιτάνια), historically known as the Tripoli region, is a historic region and former province o ...

and Spain, the Tunisian Jews claim a very old implantation on their territory. However, there is no record of their presence before the second century. Among the assumptions:

* Some historians, such as David Cazès,

Nahum Slouschz

Nahum Slouschz ( he, נחום סלושץ, links=no) (November 1872 – December 1966) was a Russian-born Israeli writer, translator and archaeologist. He was known for his studies of the "secret" Jews of Portugal and the history of the Jewish com ...

or

Alfred Louis Delattre

Alfred Louis Delattre (26 June 1850 – 12 January 1932), also known as Révérend Père Delattre, was a French archaeologist, born at Déville-lès-Rouen. Delattre made substantial discoveries in the ruins of ancient Carthage including an ancien ...

, suggest on the basis of the biblical description of the close relations based on the maritime trade between

Hiram (Phoenician king of

Tire

A tire (American English) or tyre (British English) is a ring-shaped component that surrounds a Rim (wheel), wheel's rim to transfer a vehicle's load from the axle through the wheel to the ground and to provide Traction (engineering), t ...

) and

Solomon

Solomon (; , ),, ; ar, سُلَيْمَان, ', , ; el, Σολομών, ; la, Salomon also called Jedidiah (Hebrew language, Hebrew: , Modern Hebrew, Modern: , Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: ''Yăḏīḏăyāh'', "beloved of Yahweh, Yah"), ...

(king of Israel) could have been among the founders of Phoenician counters, including that of

Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

in 814 BC.

* One of the

founding legends of the Jewish community of

Djerba

Djerba (; ar, جربة, Jirba, ; it, Meninge, Girba), also transliterated as Jerba or Jarbah, is a Tunisian island and the largest island of North Africa at , in the Gulf of Gabès, off the coast of Tunisia. It had a population of 139,544 ...

, transcribed for the first time in 1849, relates that the

Kohen

Kohen ( he, , ''kōhēn'', , "priest", pl. , ''kōhănīm'', , "priests") is the Hebrew word for " priest", used in reference to the Aaronic priesthood, also called Aaronites or Aaronides. Levitical priests or ''kohanim'' are traditionally ...

s (members of the Jewish priestly class) would have settled in present-day Tunisia after the destruction of the

Solomon's Temple

Solomon's Temple, also known as the First Temple (, , ), was the Temple in Jerusalem between the 10th century BC and . According to the Hebrew Bible, it was commissioned by Solomon in the United Kingdom of Israel before being inherited by t ...

by the Emperor

Nebuchadnezzar II

Nebuchadnezzar II (Babylonian cuneiform: ''Nabû-kudurri-uṣur'', meaning "Nabu, watch over my heir"; Biblical Hebrew: ''Nəḇūḵaḏneʾṣṣar''), also spelled Nebuchadrezzar II, was the second king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling ...

in 586 BC; They would have carried away a vestige of the destroyed Temple, preserved in the

El Ghriba synagogue in Djerba, and would have made it a place of

pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a journey, often into an unknown or foreign place, where a person goes in search of new or expanded meaning about their self, others, nature, or a higher good, through the experience. It can lead to a personal transformation, aft ...

and veneration to the present day.

However, if these hypotheses were verified, it is probable that these Israelites would have assimilated to the Punic population and sacrificed to their divinities, like

Baal

Baal (), or Baal,; phn, , baʿl; hbo, , baʿal, ). ( ''baʿal'') was a title and honorific meaning "owner", "lord" in the Northwest Semitic languages spoken in the Levant during antiquity. From its use among people, it came to be applied t ...

and

Tanit

Tanit ( Punic: 𐤕𐤍𐤕 ''Tīnīt'') was a Punic goddess. She was the chief deity of Carthage alongside her consort Baal-Hamon.

Tanit is also called Tinnit. The name appears to have originated in Carthage (modern day Tunisia), though it doe ...

. Thereafter, Jews from

Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

or

Cyrene could have settled in Carthage following the

Hellenization

Hellenization (other British spelling Hellenisation) or Hellenism is the adoption of Greek culture, religion, language and identity by non-Greeks. In the ancient period, colonization often led to the Hellenization of indigenous peoples; in the ...

of the eastern part of the

Mediterranean Basin

In biogeography, the Mediterranean Basin (; also known as the Mediterranean Region or sometimes Mediterranea) is the region of lands around the Mediterranean Sea that have mostly a Mediterranean climate, with mild to cool, rainy winters and wa ...

. The cultural context allowed them to practice Judaism more in keeping with ancestral traditions. Small Jewish communities existed in the later days of Punic domination over North Africa, without it being possible to say whether they developed or disappeared later.

Jews have in any case settled in the new

Roman province of Africa

Africa Proconsularis was a Roman province on the northern African coast that was established in 146 BC following the defeat of Carthage in the Third Punic War. It roughly comprised the territory of present-day Tunisia, the northeast of Algeri ...

, enjoying the favors of

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

. The latter, in recognition of the support of

King Antipater in his struggle against

Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a leading Roman general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of ...

, recognized Judaism and the status of

Religio licita, and according to

Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for '' The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly ...

granted the Jews a privileged status confirmed by the Magna Charta pro Judaeis under the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

. These Jews were joined by Jewish

pilgrims, expelled from Rome for proselytizing, 20 by a number of defeated in the

First Jewish–Roman War

The First Jewish–Roman War (66–73 CE), sometimes called the Great Jewish Revolt ( he, המרד הגדול '), or The Jewish War, was the first of three major rebellions by the Jews against the Roman Empire, fought in Roman-controlled ...

, deported and

resold as slaves in North Africa, and also by Jews fleeing the repression of revolts in

Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika ( ar, برقة, Barqah, grc-koi, Κυρηναϊκή ��παρχίαKurēnaïkḗ parkhíā}, after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between ...

and

Judea

Judea or Judaea ( or ; from he, יהודה, Standard ''Yəhūda'', Tiberian ''Yehūḏā''; el, Ἰουδαία, ; la, Iūdaea) is an ancient, historic, Biblical Hebrew, contemporaneous Latin, and the modern-day name of the mountainous so ...

under the reigns of the emperors

Domitian

Domitian (; la, Domitianus; 24 October 51 – 18 September 96) was a Roman emperor who reigned from 81 to 96. The son of Vespasian and the younger brother of Titus, his two predecessors on the throne, he was the last member of the Fl ...

,

Trajan

Trajan ( ; la, Caesar Nerva Traianus; 18 September 539/11 August 117) was Roman emperor from 98 to 117. Officially declared ''optimus princeps'' ("best ruler") by the senate, Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presi ...

, and

Hadrian

Hadrian (; la, Caesar Trâiānus Hadriānus ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He was born in Italica (close to modern Santiponce in Spain), a Roman ''municipium'' founded by Italic settlers in Hispania ...

. According to Josephus, the Romans deported 30,000 Jews to Carthage from Judea after the First Jewish-Roman War. It is very likely that these Jews founded communities on the territory of present-day Tunisia.

A tradition among the descendants of the first Jewish settlers was that their ancestors settled in that part of North Africa long before the destruction of the

First Temple

Solomon's Temple, also known as the First Temple (, , ), was the Temple in Jerusalem between the 10th century BC and . According to the Hebrew Bible, it was commissioned by Solomon in the United Kingdom of Israel before being inherited by th ...

in the 6th century BCE. The ruins of an ancient synagogue dating back to the 3rd–5th century CE was discovered by the French captain Ernest De Prudhomme in his

Hammam-Lif residence in 1883 called in

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

as ''sancta synagoga naronitana'' ("holy synagogue of Naro"). After the fall of the

Second Temple

The Second Temple (, , ), later known as Herod's Temple, was the reconstructed Temple in Jerusalem between and 70 CE. It replaced Solomon's Temple, which had been built at the same location in the United Kingdom of Israel before being inherited ...

, many exiled Jews settled in Tunis and engaged in agriculture, cattle-raising, and trade. They were divided into clans governed by their respective heads (''mokdem''), and had to pay the

Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

a

capitation tax

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources.

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments f ...

of 2

shekel

Shekel or sheqel ( akk, 𒅆𒅗𒇻 ''šiqlu'' or ''siqlu,'' he, שקל, plural he, שקלים or shekels, Phoenician: ) is an ancient Mesopotamian coin, usually of silver. A shekel was first a unit of weight—very roughly —and became c ...

s. Under the dominion of the Romans and (after 429) of the fairly tolerant

Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

, the Jews of Tunis increased and prospered to such a degree that

early African church councils deemed it necessary to enact restrictive laws against them. After the overthrow of the Vandals by

Belisarius

Belisarius (; el, Βελισάριος; The exact date of his birth is unknown. – 565) was a military commander of the Byzantine Empire under the emperor Justinian I. He was instrumental in the reconquest of much of the Mediterranean terr ...

in 534,

Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized '' renov ...

issued his edict of persecution in which the Jews were classed with the

Arians

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God t ...

and the

Pagans Pagans may refer to:

* Paganism, a group of pre-Christian religions practiced in the Roman Empire

* Modern Paganism, a group of contemporary religious practices

* Order of the Vine, a druidic faction in the ''Thief'' video game series

* Pagan's M ...

. As elsewhere in the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

, the

Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

of

Roman Africa were

romanized

Romanization or romanisation, in linguistics, is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, and ...

after hundreds of years of subjection and would have adopted Latinized names, worn the

toga

The toga (, ), a distinctive garment of ancient Rome, was a roughly semicircular cloth, between in length, draped over the shoulders and around the body. It was usually woven from white wool, and was worn over a tunic. In Roman historical tra ...

, and spoken Latin.

In the 7th century, the Jewish population was augmented by Spanish immigrants, who, fleeing from the persecutions of the

Visigoth

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is kn ...

ic king

Sisebut

Sisebut ( la, Sisebutus, es, Sisebuto; also ''Sisebuth'', ''Sisebur'', ''Sisebod'' or ''Sigebut'') ( 565 – February 621) was King of the Visigoths and ruler of Hispania and Septimania from 612 until his death.

Biography

He campaigned succe ...

and his successors, escaped to

Mauritania

Mauritania (; ar, موريتانيا, ', french: Mauritanie; Berber: ''Agawej'' or ''Cengit''; Pulaar: ''Moritani''; Wolof: ''Gànnaar''; Soninke:), officially the Islamic Republic of Mauritania ( ar, الجمهورية الإسلامية ...

and settled in

Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

cities.

Al-Qayrawani relates that at the time of the conquest of

Hippo Zaritus

Bizerte or Bizerta ( ar, بنزرت, translit=Binzart , it, Biserta, french: link=no, Bizérte) the classical Hippo, is a city of Bizerte Governorate in Tunisia. It is the northernmost city in Africa, located 65 km (40mil) north of the cap ...

(Arabic: ''

Bizerta

Bizerte or Bizerta ( ar, بنزرت, translit=Binzart , it, Biserta, french: link=no, Bizérte) the classical Hippo, is a city of Bizerte Governorate in Tunisia. It is the northernmost city in Africa, located 65 km (40mil) north of the cap ...

'') by

Hasan ibn al-Nu'man in 698 the governor of that district was a Jew. When Tunis came under the dominion of the

Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

, or of the Arabian

caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

of

Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

, another influx of Arabic-speaking Jews from the

Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

into Tunis took place.

Under Roman rule

The first documents attesting to the presence of Jews in Tunisia date from the second century.

Tertullian

Tertullian (; la, Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus; 155 AD – 220 AD) was a prolific early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive corpus of L ...

describes Jewish communities alongside which Pagan Jews of Punic, Roman and Berber origin and, initially, Christians; The success of Jewish proselytism led the pagan authorities to take legal measures, while Tertullian wrote a pamphlet against Judaism at the same time. On the other hand, the

Talmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law ('' halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the ce ...

mention the existence of several Carthaginian rabbis. In addition, Alfred Louis Delattre demonstrates towards the end of the nineteenth century that the

Gammarth __NOTOC__

Gammarth ( aeb, ڨمرت ) is a town on the Mediterranean Sea in the Tunis Governorate of Tunisia, located some 15 to 20 kilometres north of Tunis, adjacent to La Marsa. It is an upmarket seaside resort, known for its expensive hotels an ...

necropolis

A necropolis (plural necropolises, necropoles, necropoleis, necropoli) is a large, designed cemetery with elaborate tomb monuments. The name stems from the Ancient Greek ''nekropolis'', literally meaning "city of the dead".

The term usually im ...

, made up of 200 rock chambers, each containing up to 17 complex tombs (kokhim), contains Jewish symbols and funerary inscriptions in

Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

,

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

and

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

.

A synagogue of the 2nd or 4th century, is discovered in Naro (present

Hammam Lif

Hammam-Lif ( ar, حمام الأنف, pronounced hammam linf) is a coastal town about 20 km south-east of Tunis, the capital of Tunisia. It has been known since antiquity for its thermal springs originating in Mount Bou Kornine.

History ...

) in 1883. The mosaic covering the floor of the main hall, which includes a Latin inscription mentioning sancta synagoga naronitana ("holy synagogue of Naro") and motifs practiced throughout Roman Africa, testifies to the ease of its members and the quality of their exchanges with other populations.

Other Jewish communities are attested by epigraphic or literary references to Utique, Chemtou, Hadrumète or Thusuros (present

Tozeur). Like the other Jews of the empire, those of Roman Africa are Romanized more or less long, bear Latin or Latin names, sport the gown and speak Latin, even if they retain the knowledge of Greek, Of the Jewish diaspora at the time.

According to

St. Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afr ...

, only their morals, modeled by Jewish religious precepts (

circumcision

Circumcision is a procedure that removes the foreskin from the human penis. In the most common form of the operation, the foreskin is extended with forceps, then a circumcision device may be placed, after which the foreskin is excised. Top ...

,

Kashrut

(also or , ) is a set of dietary laws dealing with the foods that Jewish people are permitted to eat and how those foods must be prepared according to Jewish law. Food that may be consumed is deemed kosher ( in English, yi, כּשר), fr ...

, observance of

Shabbat

Shabbat (, , or ; he, שַׁבָּת, Šabbāṯ, , ) or the Sabbath (), also called Shabbos (, ) by Ashkenazim, is Judaism's day of rest on the seventh day of the week—i.e., Saturday. On this day, religious Jews remember the biblical stori ...

,

modesty of dress), distinguish them from the rest of the population. On the intellectual level, they devote themselves to translation for Christian clients and to the study of the Law, many Rabbis were originally from Carthage. From an economic point of view, they worked in agriculture, livestock and trade. Their situation is modified from the edict of Milan (313) which legalized Christianity. Jews were gradually excluded from most public functions and proselytism was severely punished. The construction of new synagogues was forbidden towards the end of the fourth century and their maintenance without the agreement of the authorities, under a law of 423.

However, various councils held by the

Church of Carthage

The Archdiocese of Carthage, also known as the Church of Carthage, was a Latin Catholic diocese established in Carthage, Roman Empire, in the 2nd century. Agrippin was the first named bishop, around 230 AD. The temporal importance of the city of ...

, recommending Christians not to follow certain practices of their Jewish neighbors, testify to the maintenance of their influence.

From Vandal peace to Byzantine repression

At the beginning of the 5th century the arrival of the

Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

has opened a period of respite for the Jews. The

Arianism

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God ...

of the new masters of Roman Africa was closer to the Jewish religion than the Catholicism of the

Church Fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical per ...

. The Jews probably thrived economically, backing the

Vandal kings against the armies of

Emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife ( empress consort), mother ( ...

Justinian

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized '' renova ...

, who had set out to conquer North Africa.

Justinian's victory in 535 opened the period of the

Exarchate of Africa

The Exarchate of Africa was a division of the Byzantine Empire around Carthage that encompassed its possessions on the Western Mediterranean. Ruled by an exarch (viceroy), it was established by the Emperor Maurice in the late 580s and survive ...

, which saw the persecution of the Jews with the Arians, the Donatists and the Gentiles. Stigmatized again, they are excluded from any public office, their synagogues are transformed into churches, their worship is proscribed and their meetings forbidden. The administration strictly applies the

Codex Theodosianus

The ''Codex Theodosianus'' (Eng. Theodosian Code) was a compilation of the laws of the Roman Empire under the Christian emperors since 312. A commission was established by Emperor Theodosius II and his co-emperor Valentinian III on 26 March 42 ...

against them, which allows the holding of

forced conversions. If the emperor

Maurice Maurice may refer to:

People

* Saint Maurice (died 287), Roman legionary and Christian martyr

* Maurice (emperor) or Flavius Mauricius Tiberius Augustus (539–602), Byzantine emperor

*Maurice (bishop of London) (died 1107), Lord Chancellor and ...

attempts to repeal these measures, his successors return there and an

imperial edict imposes

baptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost ...

on them.

Some Jews have fled the Byzantine-controlled cities to settle in the mountains or on the confines of the desert and fight there with the support of the

Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–19 ...

tribes, many of whom would have been won by their proselytism. According to other historians, the Judaization of the Berbers would have taken place four centuries earlier, with the arrival of Jews fleeing the repression of the Cyrenaic revolt; The transition would have been made progressively through a Judeo-Pagan

syncretism

Syncretism () is the practice of combining different beliefs and various schools of thought. Syncretism involves the merging or assimilation of several originally discrete traditions, especially in the theology and mythology of religion, thu ...

with the cult of

Tanit

Tanit ( Punic: 𐤕𐤍𐤕 ''Tīnīt'') was a Punic goddess. She was the chief deity of Carthage alongside her consort Baal-Hamon.

Tanit is also called Tinnit. The name appears to have originated in Carthage (modern day Tunisia), though it doe ...

, still anchored after the fall of Carthage. Whatever the hypothesis, the historian of the fourteenth century

Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldun (; ar, أبو زيد عبد الرحمن بن محمد بن خلدون الحضرمي, ; 27 May 1332 – 17 March 1406, 732-808 AH) was an Arab

The Historical Muhammad', Irving M. Zeitlin, (Polity Press, 2007), p. 21; "It is, of ...

confirms their existence on the eve of the

Muslim conquest of the Maghreb

The Muslim conquest of the Maghreb ( ar, الْفَتْحُ الإسلَامِيُّ لِلْمَغرِب) continued the century of rapid Muslim conquests following the death of Muhammad in 632 and into the Byzantine-controlled territories of ...

on the basis of eleventh-century Arab chronicles. However, this version is fairly questioned: Haim Zeev Hirschberg recalls that the historian wrote his work several centuries after the facts,

Mohamed Talbi

Mohamed Talbi ( ar, محمد الطالبي), (16 September 1921 – 1 May 2017) was a Tunisian historian and professor. He was the author of many books about Islam.

Biography

Professor Emeritus at University of Tunis, Mohamed Talbi was a Tunis ...

that the French translation is not totally exact since it does not render the idea of the contingency expressed by the author, and

Gabriel Camps

Gabriel Camps (May 20, 1927 – September 7, 2002) was a French archaeologist and social anthropologist, the founder of the '' Encyclopédie berbère'' and is considered a prestigious scholar on the history of the Berber people.

Biography

Gabrie ...

that the

Jarawa and Nefzaouas quoted were of Christian confession before the arrival of

Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

.

In any case, even if the hypothesis of the massive conversion of whole tribes appears fragile, individual conversions seem more probable.

Middle Ages

New status of Jews under Islam

With the Arab conquest and the arrival of Islam in Tunisia in the eighth century, the "

People of the Book

People of the Book or Ahl al-kitāb ( ar, أهل الكتاب) is an Islamic term referring to those religions which Muslims regard as having been guided by previous revelations, generally in the form of a scripture. In the Quran they are ide ...

" (including Jews and Christians) were given a choice between conversion to Islam (which some Jewish Berbers have done) and submission to the

dhimma

' ( ar, ذمي ', , collectively ''/'' "the people of the covenant") or () is a historical term for non-Muslims living in an Islamic state with legal protection. The word literally means "protected person", referring to the state's obligatio ...

. The Dhimma is a pact of protection allowing the non-Muslims to practice their worship, to administer according to their laws and have their property and lives saved in return for the payment of the

jizya

Jizya ( ar, جِزْيَة / ) is a per capita yearly taxation historically levied in the form of financial charge on dhimmis, that is, permanent non-Muslim subjects of a state governed by Islamic law. The jizya tax has been understood in ...

, capitation tax levied on the free men, the wearing of distinctive clothing and the lack of construction of new places of worship. Moreover, dhimmis couldn't marry Muslim women – the reverse was possible if the Jewish wife converted and proselytized. They must also treat Muslims and Islam with respect and humility. Any violation of this pact resulted in expulsion or even death.

Jews were economically, culturally and linguistically integrated into society, while retaining their cultural and religious peculiarities. If it is slow, arabization is faster in urban areas, following the arrival of Jews from the East in the wake of the

Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

, and in the wealthy classes.

In 788, when

Idris I of Morocco

Idris (I) ibn Abd Allah ( ar, إدريس بن عبد الله, translit=Idrīs ibn ʿAbd Allāh), also known as Idris the Elder ( ar, إدريس الأكبر, translit=Idrīs al-Akbar), (d. 791) was an Arab Hasanid Sharif and the founder of the ...

(Imam Idris) proclaimed

Mauritania

Mauritania (; ar, موريتانيا, ', french: Mauritanie; Berber: ''Agawej'' or ''Cengit''; Pulaar: ''Moritani''; Wolof: ''Gànnaar''; Soninke:), officially the Islamic Republic of Mauritania ( ar, الجمهورية الإسلامية ...

's independence of the

Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttal ...

of

Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

, the Tunisian Jews joined his army under the leadership of their chief, Benjamin ben Joshaphat ben Abiezer. They soon withdrew, however; primarily because they were loath to fight against their coreligionists of other parts of Mauritania, who remained faithful to the caliphate of Baghdad; and secondarily, because of some indignities committed by Idris against Jewish women. The victorious Idris avenged this defection by attacking the Jews in their cities. The Jews were required to pay a capitation-tax and provide a certain number of virgins annually for Idris'

harem

Harem ( Persian: حرمسرا ''haramsarā'', ar, حَرِيمٌ ''ḥarīm'', "a sacred inviolable place; harem; female members of the family") refers to domestic spaces that are reserved for the women of the house in a Muslim family. A har ...

. The Jewish tribe 'Ubaid Allah preferred to migrate to the east rather than to submit to Idris; according to a tradition, the Jews of the island of

Djerba

Djerba (; ar, جربة, Jirba, ; it, Meninge, Girba), also transliterated as Jerba or Jarbah, is a Tunisian island and the largest island of North Africa at , in the Gulf of Gabès, off the coast of Tunisia. It had a population of 139,544 ...

are the descendants of that tribe. In 793 Imam Idris was poisoned at the command of

caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

Harun al-Rashid

Abu Ja'far Harun ibn Muhammad al-Mahdi ( ar

, أبو جعفر هارون ابن محمد المهدي) or Harun ibn al-Mahdi (; or 766 – 24 March 809), famously known as Harun al-Rashid ( ar, هَارُون الرَشِيد, translit=Hārūn ...

(it is said, by the governor's physician Shamma, probably a Jew), and circa 800 the

Aghlabite dynasty was established. Under the rule of this dynasty, which lasted until 909, the situation of the Jews in Tunis was very favorable. As of old, Bizerta had a Jewish governor, and the political influence of the Jews made itself felt in the administration of the country. Especially prosperous at that time was the community of

Kairwan

Kairouan (, ), also spelled El Qayrawān or Kairwan ( ar, ٱلْقَيْرَوَان, al-Qayrawān , aeb, script=Latn, Qeirwān ), is the capital of the Kairouan Governorate in Tunisia and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The city was founded by t ...

(

Kairouan

Kairouan (, ), also spelled El Qayrawān or Kairwan ( ar, ٱلْقَيْرَوَان, al-Qayrawān , aeb, script=Latn, Qeirwān ), is the capital of the Kairouan Governorate in Tunisia and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The city was founded by t ...

), which was established soon after the foundation of that city by

Uqba bin Nafi in the year 670.

A period of reaction set in with the accession of the

Zirite Al-Mu'izz (1016–62), who persecuted all heterodox sects, as well as the Jews. The persecution was especially detrimental to the prosperity of the Kairwan community, and members thereof began to emigrate to the city of Tunis, which speedily gained in population and in commercial importance.

The accession of the

Almohad

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the unity of God) was a North African Berber Muslim empire fou ...

dynasty to the throne of the

Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ar, الْمَغْرِب, al-Maghrib, lit=the west), also known as the Arab Maghreb ( ar, المغرب العربي) and Northwest Africa, is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, ...

provinces in 1146 proved disastrous to the Jews of Tunis. The first Almohad, '

Abd al-Mu'min

Abd al Mu'min (c. 1094–1163) ( ar, عبد المؤمن بن علي or عبد المومن الــكـومي; full name: ʿAbd al-Muʾmin ibn ʿAlī ibn ʿAlwī ibn Yaʿlā al-Kūmī Abū Muḥammad) was a prominent member of the Almohad mov ...

, claimed that

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mon ...

had permitted the Jews free exercise of their religion for only five hundred years, and had declared that if, after that period, the

messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of '' mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach ...

had not come, they were to be forced to embrace

Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

. Accordingly, Jews as well as Christians were compelled either to embrace Islam or to leave the country. 'Abd al-Mu'min's successors pursued the same course, and their severe measures resulted either in emigration or in forcible conversions. Soon becoming suspicious of the sincerity of the new converts, the Almohadis compelled them to wear a

special garb, with a yellow cloth for a head-covering.

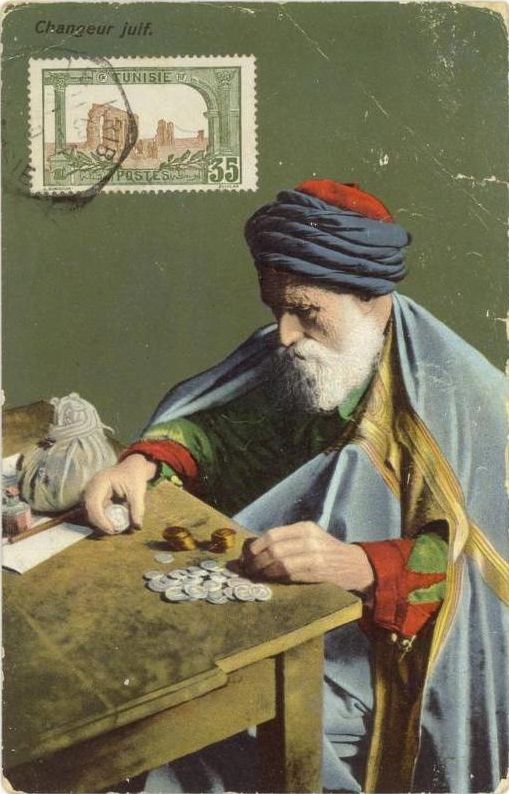

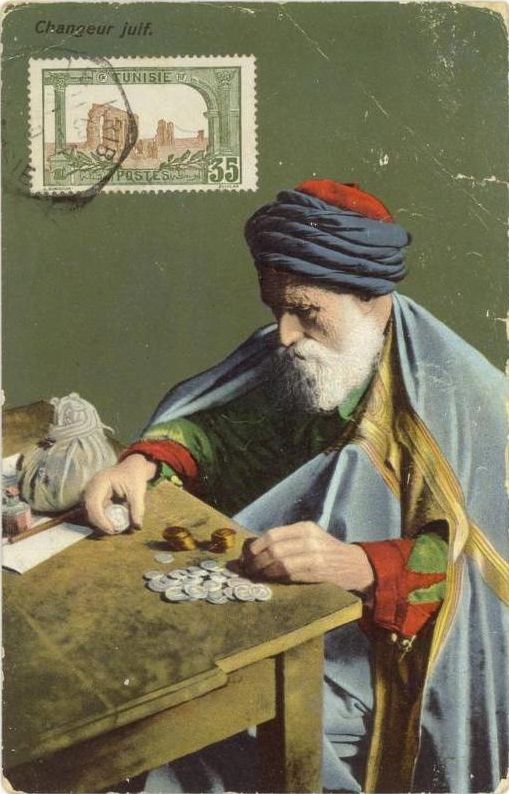

Cultural heyday of Tunisian Jews.

The living conditions of the Jews were relatively favorable during the reign of the

Aghlabids

The Aghlabids ( ar, الأغالبة) were an Arab dynasty of emirs from the Najdi tribe of Banu Tamim, who ruled Ifriqiya and parts of Southern Italy, Sicily, and possibly Sardinia, nominally on behalf of the Abbasid Caliph, for about a ...

and then Fatimids dynasties. As evidenced by the archives of the

Cairo Geniza

The Cairo Geniza, alternatively spelled Genizah, is a collection of some 400,000 Jewish manuscript fragments and Fatimid administrative documents that were kept in the ''genizah'' or storeroom of the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Fustat or Old Cairo, ...

, composed between 800 and 115041, the

dhimma

' ( ar, ذمي ', , collectively ''/'' "the people of the covenant") or () is a historical term for non-Muslims living in an Islamic state with legal protection. The word literally means "protected person", referring to the state's obligatio ...

is practically limited to the

jizya

Jizya ( ar, جِزْيَة / ) is a per capita yearly taxation historically levied in the form of financial charge on dhimmis, that is, permanent non-Muslim subjects of a state governed by Islamic law. The jizya tax has been understood in ...

.

Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

worked in the service of the dynasty, as treasurers, doctors or tax collectors but their situation remained precarious.

Kairouan

Kairouan (, ), also spelled El Qayrawān or Kairwan ( ar, ٱلْقَيْرَوَان, al-Qayrawān , aeb, script=Latn, Qeirwān ), is the capital of the Kairouan Governorate in Tunisia and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The city was founded by t ...

, now the capital of the Aghlabids, was the seat of the most important community in the territory, attracting migrants from Umayyad, Italy and the Abbasid Empire. This community would become one of the major poles of Judaism between the ninth and eleventh centuries, both economically, culturally and intellectually, ensuring, through correspondence with the

Talmudic Academies in Babylonia, Lessons learned from Spain.

Many major figures of Judaism are associated with the city. Among them is

Isaac Israeli ben Solomon

Isaac Israeli ben Solomon (Hebrew: יצחק בן שלמה הישראלי, ''Yitzhak ben Shlomo ha-Yisraeli''; Arabic: أبو يعقوب إسحاق بن سليمان الإسرائيلي, ''Abu Ya'qub Ishaq ibn Suleiman al-Isra'ili'') ( 832 &ndas ...

, a private doctor of the Aghlabide Ziadet Allah III and then of the Fatimids

Abdullah al-Mahdi Billah

Abū Muḥammad ʿAbd Allāh/ʿUbayd Allāh ibn al-Ḥusayn (), 873 – 4 March 934, better known by his regnal name al-Mahdi Billah, was the founder of the Isma'ili Fatimid Caliphate, the only major Shi'a caliphate in Islamic history, and the ...

and

Al-Qa'im bi-Amr Allah and author of various medical

treatise

A treatise is a formal and systematic written discourse on some subject, generally longer and treating it in greater depth than an essay, and more concerned with investigating or exposing the principles of the subject and its conclusions." Tre ...

s in Arabic which would enrich the medieval medicine through their translation by

Constantine the African

Constantine the African ( la, Constantinus Africanus; died before 1098/1099, Monte Cassino) was a physician who lived in the 11th century. The first part of his life was spent in Ifriqiya and the rest in Italy. He first arrived in Italy in the ...

, adapting the teachings of the

Alexandrian school to the Jewish dogma.

Dunash ibn Tamim

Dunash ibn Tamim ( he, דונש אבן תמים) was a Jewish tenth century scholar, and a pioneer of scientific study among Arabic-speaking Jews. His Arabic name was أبو سهل ''Abu Sahl''; his surname, according to an isolated statement of M ...

, is the author (or final editor) whose discipline is a philosophical commentary on the

Sefer Yetzirah

''Sefer Yetzirah'' ( ''Sēp̄er Yəṣīrā'', ''Book of Formation'', or ''Book of Creation'') is the title of a book on Jewish mysticism, although some early commentators treated it as a treatise on mathematical and linguistic theory as opposed ...

, where he developed conceptions close to his master's thought. Another disciple, Ishaq ibn Imran is considered the founder of the philosophical and medical school of

Ifriqiya

Ifriqiya ( '), also known as al-Maghrib al-Adna ( ar, المغرب الأدنى), was a medieval historical region comprising today's Tunisia and eastern Algeria, and Tripolitania (today's western Libya). It included all of what had previously ...

.

Jacob ben Nissim ibn Shahin, rector of the Center of Studies at the end of the tenth century, is the official representative of the Talmudic academies of Babylonia, acting as intermediaries between them and his own community. His successor

Chushiel

Chushiel ben Elchanan (also Ḥushiel) was president of the bet ha-midrash at Kairouan, Tunisia toward the end of the 10th century. He was most probably born in Italy, but his origins and travels remain obscure, and his eventual arrival in Kairwa ...

ben Elchanan, originally from

Bari

Bari ( , ; nap, label= Barese, Bare ; lat, Barium) is the capital city of the Metropolitan City of Bari and of the Apulia region, on the Adriatic Sea, southern Italy. It is the second most important economic centre of mainland Southern Ital ...

, developed the simultaneous study of the Talmud of Babylon and the

Jerusalem Talmud

The Jerusalem Talmud ( he, תַּלְמוּד יְרוּשַׁלְמִי, translit=Talmud Yerushalmi, often for short), also known as the Palestinian Talmud or Talmud of the Land of Israel, is a collection of rabbinic notes on the second-century ...

. His son and disciple

Chananel ben Chushiel was one of the major commentators of the Talmud in the Middle Ages. After his death, his work was continued by another disciple of his father whom

Ignác Goldziher

Ignác (Yitzhaq Yehuda) Goldziher (22 June 1850 – 13 November 1921), often credited as Ignaz Goldziher, was a Hungarian scholar of Islam. Along with the German Theodor Nöldeke and the Dutch Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje, he is considered the ...

calls Jewish :

Nissim ben Jacob, the only one among the sages of Kairouan to bear the title of

Gaon, also wrote an important commentary on the Talmud and the Hibbour yafe mehayeshoua, which is perhaps the first tales collection in Jewish literature.

On the political level, the community emancipated itself from the

exile

Exile is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons and peoples suf ...

of

Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

at the beginning of the eleventh century and acquired its first secular chief. Each community was placed under the authority of a council of notables headed by a chief (naggid) who, through the faithful, disposes of the resources necessary for the proper functioning of the various institutions: worship, schools, a tribunal headed by the rabbi- Judge (dayan), etc. The maggid of Kairouan undoubtedly had the ascendancy over those of the communities of smaller size.

The Jews participate greatly in the exchanges with

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the M ...

,

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

and the Middle East. Grouped in separate quarters (although many Jews settled in the Muslim districts of Kairouan during the Fatimid period), they had house of prayer, schools and a court.

The port cities of

Mahdia

Mahdia ( ar, المهدية ') is a Tunisian coastal city with 62,189 inhabitants, south of Monastir and southeast of Sousse.

Mahdia is a provincial centre north of Sfax. It is important for the associated fish-processing industry, as well as w ...

,

Sousse

Sousse or Soussa ( ar, سوسة, ; Berber:''Susa'') is a city in Tunisia, capital of the Sousse Governorate. Located south of the capital Tunis, the city has 271,428 inhabitants (2014). Sousse is in the central-east of the country, on the Gulf ...

,

Sfax

Sfax (; ar, صفاقس, Ṣafāqis ) is a city in Tunisia, located southeast of Tunis. The city, founded in AD849 on the ruins of Berber Taparura, is the capital of the Sfax Governorate (about 955,421 inhabitants in 2014), and a Mediterrane ...

and

Gabès

Gabès (, ; ar, قابس, ), also spelled Cabès, Cabes, Kabes, Gabbs and Gaps, is the capital city of the Gabès Governorate in Tunisia. It is located on the coast of the Gulf of Gabès. With a population of 152,921, Gabès is the 6th largest ...

saw a steady influx of Jewish immigrants from the

Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

to the end of the eleventh century, and their communities participated in these economic and intellectual exchanges. Monopolizing the goldsmiths' and jewelers' crafts, they also worked in the textile industry, as tailors, tanners and shoemakers, while the smallest rural communities practiced agriculture (saffron, henna, vine, etc.) or breeding of nomadic animals.

Under the Hafsids, Spanish and Ottomans (1236–1603)

The departure of the Fatimids to

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

in 972 led their

Zirid

The Zirid dynasty ( ar, الزيريون, translit=az-zīriyyūn), Banu Ziri ( ar, بنو زيري, translit=banū zīrī), or the Zirid state ( ar, الدولة الزيرية, translit=ad-dawla az-zīriyya) was a Sanhaja Berber dynasty from m ...

vassals to seize power and eventually break their bonds of political and religious submission in the middle of the eleventh century. The

Banu Hilal

The Banu Hilal ( ar, بنو هلال, translit=Banū Hilāl) was a confederation of Arabian tribes from the Hejaz and Najd regions of the Arabian Peninsula that emigrated to North Africa in the 11th century. Masters of the vast plateaux of t ...

and the

Banu Sulaym

The Banu Sulaym ( ar, بنو سليم) is an Arab tribe that dominated part of the Hejaz in the pre-Islamic era. They maintained close ties with the Quraysh of Mecca and the inhabitants of Medina, and fought in a number of battles against the I ...

, were sent in retaliation against Tunisia by the Fatimids, took Kairouan in 1057 and plundered it, which empties it of all its population then plunges it into the doldrums. Combined with the triumph of

Sunnism and the end of the Babylonian

gaonate, these events marked the end of the Kairouan community and reversed the migratory flow of the Jewish populations towards the

Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

, with the elites having already accompanied the Fatimid court in

Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

. Jews have migrated to the coastal cities of

Gabes,

Sfax

Sfax (; ar, صفاقس, Ṣafāqis ) is a city in Tunisia, located southeast of Tunis. The city, founded in AD849 on the ruins of Berber Taparura, is the capital of the Sfax Governorate (about 955,421 inhabitants in 2014), and a Mediterrane ...

,

Mahdia

Mahdia ( ar, المهدية ') is a Tunisian coastal city with 62,189 inhabitants, south of Monastir and southeast of Sousse.

Mahdia is a provincial centre north of Sfax. It is important for the associated fish-processing industry, as well as w ...

,

Sousse

Sousse or Soussa ( ar, سوسة, ; Berber:''Susa'') is a city in Tunisia, capital of the Sousse Governorate. Located south of the capital Tunis, the city has 271,428 inhabitants (2014). Sousse is in the central-east of the country, on the Gulf ...

and

Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

, but also to

Béjaïa

Béjaïa (; ; ar, بجاية, Latn, ar, Bijāya, ; kab, Bgayet, Vgayet), formerly Bougie and Bugia, is a Mediterranean port city and commune on the Gulf of Béjaïa in Algeria; it is the capital of Béjaïa Province, Kabylia. Béjaïa is ...

,

Tlemcen

Tlemcen (; ar, تلمسان, translit=Tilimsān) is the second-largest city in northwestern Algeria after Oran, and capital of the Tlemcen Province. The city has developed leather, carpet, and textile industries, which it exports through the p ...

and

Beni Hammad Fort

Qal'at Bani Hammad ( ar, قلعة بني حماد), also known as Qal'a Bani Hammad or Qal'at of the Beni Hammad (among other variants), is a fortified palatine city in Algeria. Now in ruins, in the 11th century, it served as the first capital o ...

.

Under the

Hafsid dynasty

The Hafsids ( ar, الحفصيون ) were a Sunni Muslim dynasty of Berber descentC. Magbaily Fyle, ''Introduction to the History of African Civilization: Precolonial Africa'', (University Press of America, 1999), 84. who ruled Ifriqiya (wester ...

, which was established in 1236 as a breakaway from the

Almohad dynasty

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the unity of God) was a North African Berber Muslim empire fou ...

, the condition of the Jews greatly improved. Besides Kairwan, there were at that time important communities in

Mehdia

Mahdia ( ar, المهدية ') is a Tunisian coastal city with 62,189 inhabitants, south of Monastir and southeast of Sousse.

Mahdia is a provincial centre north of Sfax. It is important for the associated fish-processing industry, as well as w ...

,

Kalaa, the island of

Djerba

Djerba (; ar, جربة, Jirba, ; it, Meninge, Girba), also transliterated as Jerba or Jarbah, is a Tunisian island and the largest island of North Africa at , in the Gulf of Gabès, off the coast of Tunisia. It had a population of 139,544 ...

, and the city of Tunis. Considered at first as foreigners, the Jews were not permitted to settle in the interior of Tunis, but had to live in a building called a ''funduk''. Subsequently, however, a wealthy and humane

Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

,

Sidi Mahrez

Sidi Mahrez ben Khalaf or Abu Mohamed Mahrez ben Khalaf ben Zayn ( ar, سيدي محرز بن خلف; 951–1022) was a Tunisian Wali, scholar of the Maliki school of jurisprudence and a Qadi. He is considered to be the patron-saint of the city of ...

, who in 1159 had rendered great services to the Almohad caliph

Abd al-Mu'min

Abd al Mu'min (c. 1094–1163) ( ar, عبد المؤمن بن علي or عبد المومن الــكـومي; full name: ʿAbd al-Muʾmin ibn ʿAlī ibn ʿAlwī ibn Yaʿlā al-Kūmī Abū Muḥammad) was a prominent member of the Almohad mov ...

, obtained for them the right to settle in a special quarter of the city. This quarter, called the "Hira," constituted until 1857 the

ghetto

A ghetto, often called ''the'' ghetto, is a part of a city in which members of a minority group live, especially as a result of political, social, legal, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished ...

of Tunis; it was closed at night. In 1270, in consequence of the defeat of

Louis IX of France

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), commonly known as Saint Louis or Louis the Saint, was King of France from 1226 to 1270, and the most illustrious of the Direct Capetians. He was crowned in Reims at the age of 12, following the d ...

, who had undertaken a crusade against Tunis, the cities of Kairwan and Ḥammat were declared holy; and the Jews were required either to leave them or to convert to Islam. From that year until the conquest of Tunis by France (1857), Jews and Christians were forbidden to pass a night in either of these cities; and only by special permission of the governor were they allowed to enter them during the day.

The rise of the

Almohad Caliphate

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the unity of God) was a North African Berber Muslim empire ...

shaked both the Jewish communities of Tunisia and the Muslims attached to the cult of the saints, declared by the new sovereigns as

heretics

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

. Jews were forced to

apostasy

Apostasy (; grc-gre, ἀποστασία , 'a defection or revolt') is the formal disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion that ...

by Caliph

Abd al-Mu'min

Abd al Mu'min (c. 1094–1163) ( ar, عبد المؤمن بن علي or عبد المومن الــكـومي; full name: ʿAbd al-Muʾmin ibn ʿAlī ibn ʿAlwī ibn Yaʿlā al-Kūmī Abū Muḥammad) was a prominent member of the Almohad mov ...

. Many massacres took place, despite many formal conversions by the pronunciation of the

Shahada

The ''Shahada'' ( Arabic: ٱلشَّهَادَةُ , "the testimony"), also transliterated as ''Shahadah'', is an Islamic oath and creed, and one of the Five Pillars of Islam and part of the Adhan. It reads: "I bear witness that there i ...

. Indeed, many Jews, while outwardly professing Islam, remained faithful to their religion, which they observed in secret, as advocated by

Rabbi Moses ben Maimon. Jewish practices disappeared from the Maghreb from 1165 to 1230; Still they were saddened by the sincere adherence of some to Islam, fears of persecution and the relativization of any religious affiliation. This Islamization of the morals and doctrines of the Jews of Tunisia, meant they as 'dhimmis' (after the disappearance of Christianity in the Maghreb around 1150) isolated from their other coreligionists, and was strongly criticized by the

Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah ...

.

Under the

Hafsid dynasty

The Hafsids ( ar, الحفصيون ) were a Sunni Muslim dynasty of Berber descentC. Magbaily Fyle, ''Introduction to the History of African Civilization: Precolonial Africa'', (University Press of America, 1999), 84. who ruled Ifriqiya (wester ...

, which emancipated from the Almohads and their religious doctrine in 1236, the Jews reconstituted the communities that existed before the Almohad period. The

dhimma

' ( ar, ذمي ', , collectively ''/'' "the people of the covenant") or () is a historical term for non-Muslims living in an Islamic state with legal protection. The word literally means "protected person", referring to the state's obligatio ...

was strict, especially in matters of dress, but systematic persecution, social exclusion and hindrance to worship had disappeared. New trades appeared:

carpenter

Carpentry is a skilled trade and a craft in which the primary work performed is the cutting, shaping and installation of building materials during the construction of buildings, ships, timber bridges, concrete formwork, etc. Carpenters t ...

,

blacksmith

A blacksmith is a metalsmith who creates objects primarily from wrought iron or steel, but sometimes from other metals, by forging the metal, using tools to hammer, bend, and cut (cf. tinsmith). Blacksmiths produce objects such as gates, gr ...

, chiseler or soap-maker; Some worked in the service of power, striking money, collecting customs duties or translating.

Although the difficulty of the economic context leads to a surge of

probabilism

In theology and philosophy, probabilism (from Latin ''probare'', to test, approve) is an ancient Greek doctrine of Academic skepticism. It holds that in the absence of certainty, plausibility or truth-likeness is the best criterion. The term can a ...

, the triumph of

Maliki

The ( ar, مَالِكِي) school is one of the four major schools of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas in the 8th century. The Maliki school of jurisprudence relies on the Quran and hadiths as prima ...

Sunnism with little tolerance towards the "people of the book" meant material and spiritual misery. The massive settlement of Jewish-Spanish scholars fleeing from the

Castile in 1391 and again in 1492 was mainly carried out in

Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

and

Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to A ...

, and the Tunisian Jews, abandoned by this phenomenon, were led to consult Algerian scholars such as

Simeon ben Zemah Duran

Simeon ben Zemah Duran, also Tzemach Duran (1361–1444; ), known as Rashbatz () or Tashbatz was a Rabbinical authority, student of philosophy, astronomy, mathematics, and especially of medicine, which he practised for a number of years at Palm ...

.

In the 14th and 15th centuries, the Jews of Tunis were treated more cruelly than those elsewhere in the Maghreb. While refugees from Spain and

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of th ...

flocked to

Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

and

Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to A ...

, only some chose to settle in Tunis. The Tunisian Jews had no eminent rabbis or scholars and had to consult those of Algeria or Morocco on religious questions. In the fifteenth century, each community was autonomous – recognized by power from the moment it counts at least ten major men – and has its own institutions; Their communal affairs were directed by a chief (zaken ha-yehudim) nominated by the government, and assisted by a council of notables (gdolei ha-qahal) made up of the most educated and wealthy family heads. The chief's functions consisted in the administration of justice among the Jews and collection of Jewish taxes.

Three kinds of taxes were imposed on Tunisian Jews:

# a communal tax, to which every member contributed according to his means;

# a personal or capitation tax (the ''

jizya

Jizya ( ar, جِزْيَة / ) is a per capita yearly taxation historically levied in the form of financial charge on dhimmis, that is, permanent non-Muslim subjects of a state governed by Islamic law. The jizya tax has been understood in ...

'');

# a general tax, which was levied upon the Muslims also.

In addition to these, every Jewish tradesman and industrialist had to pay an annual tax to the guild. After the 13th century, taxes were collected by a qaid, who also served as an intermediary between the government and the Jews. His authority within the Jewish community was supreme. The members of the council of elders, as well as the rabbis, were nominated at his recommendation, and no rabbinical decision was valid unless approved by him.

During the Conquest of Tunis (1535), conquest of Tunis by the Spaniards in 1535, many Jews were made prisoners and sold as slaves in several Christian countries. After the victory of the Ottomans over the Spaniards in 1574, Tunisia became a province of the Ottoman Empire led by deys, from 1591, then by beys, from 1640. In this context, Jews arriving from Italy have played an important role in the life of the country and in the history of Tunisian Judaism.

During the Spanish occupation of the Tunisian coasts (1535–74) the Jewish communities of Bizerte, Susa,

Sfax

Sfax (; ar, صفاقس, Ṣafāqis ) is a city in Tunisia, located southeast of Tunis. The city, founded in AD849 on the ruins of Berber Taparura, is the capital of the Sfax Governorate (about 955,421 inhabitants in 2014), and a Mediterrane ...

, and other seaports suffered greatly at the hands of the conquerors; while under the subsequent Ottoman Empire, Turkish rule the Jews of Tunis enjoyed a fair amount of security. They were free to practice their religion and administer their own affairs. Nevertheless, they were subject to the caprices of princes and outbursts of fanaticism. Petty officials were allowed to impose upon them the most difficult drudgery without compensation. They were obliged to wear a special costume, consisting of a blue frock without collar or ordinary sleeves (loose linen sleeves being substituted), wide linen drawers, black slippers, and a small black skull-cap; stockings might be worn in winter only. They might ride only on asses or mules, and were not permitted to use a saddle.

Beginning of the Modern Era