Tube Alloys on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Tube Alloys was the research and development programme authorised by the United Kingdom, with participation from Canada, to develop nuclear weapons during the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. Starting before the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

in the United States, the British efforts were kept classified, and as such had to be referred to by code even within the highest circles of government.

The possibility of nuclear weapons was acknowledged early in the war. At the University of Birmingham

The University of Birmingham (informally Birmingham University) is a Public university, public research university located in Edgbaston, Birmingham, United Kingdom. It received its royal charter in 1900 as a successor to Queen's College, Birmingha ...

, Rudolf Peierls

Sir Rudolf Ernst Peierls, (; ; 5 June 1907 – 19 September 1995) was a German-born British physicist who played a major role in Tube Alloys, Britain's nuclear weapon programme, as well as the subsequent Manhattan Project, the combined Allie ...

and Otto Robert Frisch

Otto Robert Frisch FRS (1 October 1904 – 22 September 1979) was an Austrian-born British physicist who worked on nuclear physics. With Lise Meitner he advanced the first theoretical explanation of nuclear fission (coining the term) and firs ...

co-wrote a memorandum explaining that a small mass of pure uranium-235

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exi ...

could be used to produce a chain reaction in a bomb with the power of thousands of tons of TNT

Trinitrotoluene (), more commonly known as TNT, more specifically 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene, and by its preferred IUPAC name 2-methyl-1,3,5-trinitrobenzene, is a chemical compound with the formula C6H2(NO2)3CH3. TNT is occasionally used as a reagen ...

. This led to the formation of the MAUD Committee, which called for an all-out effort to develop nuclear weapons. Wallace Akers

Sir Wallace Alan Akers (9 September 1888 – 1 November 1954) was a British chemist and industrialist. Beginning his academic career at Oxford he specialized in physical chemistry. During the Second World War, he was the director of the Tube Al ...

, who oversaw the project, chose the deliberately misleading code name "Tube Alloys". His Tube Alloys Directorate was part of the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, abbreviated DSIR was the name of several British Empire organisations founded after the 1923 Imperial Conference to foster intra-Empire trade and development.

* Department of Scientific and Industria ...

.

The Tube Alloys programme in Britain and Canada was the first nuclear weapons project. Due to the high costs, and the fact that Britain was fighting a war within bombing range of its enemies, Tube Alloys was ultimately subsumed into the Manhattan Project by the Quebec Agreement with the United States, under which the two nations agreed to share nuclear weapons technology, and to refrain from using it against each other, or against other countries without mutual consent; but the United States did not provide complete details of the results of the Manhattan Project to the United Kingdom. The Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

gained valuable information through its atomic spies

Atomic spies or atom spies were people in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada who are known to have illicitly given information about nuclear weapons production or design to the Soviet Union during World War II and the early ...

, who had infiltrated both the British and American projects.

The United States terminated co-operation after the war ended with the Atomic Energy Act of 1946. This prompted the United Kingdom to relaunch its own project, High Explosive Research. Production facilities were established and British scientists continued their work under the auspices of an independent British programme. Finally, in 1952, Britain performed a nuclear test

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, Nuclear weapon yield, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detona ...

under codename "Operation Hurricane

Operation Hurricane was the first test of a British atomic device. A plutonium implosion device was detonated on 3 October 1952 in Main Bay, Trimouille Island, in the Montebello Islands in Western Australia. With the success of Operation H ...

". In 1958, in the wake of the Sputnik crisis and the British demonstration of a two-stage thermonuclear bomb

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

, the United Kingdom and the United States signed US–UK Mutual Defence Agreement

The US–UK Mutual Defense Agreement, or 1958 UK–US Mutual Defence Agreement, is a bilateral treaty between the United States and the United Kingdom on nuclear weapons co-operation. The treaty's full name is Agreement between the Government ...

, which resulted in a resumption of Britain's nuclear Special Relationship with the United States.

Origins

Discovery of fission

Theneutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , which has a neutral (not positive or negative) charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. Protons and neutrons constitute the nuclei of atoms. Since protons and neutrons beh ...

was discovered by James Chadwick

Sir James Chadwick, (20 October 1891 – 24 July 1974) was an English physicist who was awarded the 1935 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the neutron in 1932. In 1941, he wrote the final draft of the MAUD Report, which inspi ...

at the Cavendish Laboratory at the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209 and granted a royal charter by Henry III in 1231, Cambridge is the world's third oldest surviving university and one of its most pr ...

in February 1932. In April 1932, his Cavendish colleagues John Cockcroft

Sir John Douglas Cockcroft, (27 May 1897 – 18 September 1967) was a British physicist who shared with Ernest Walton the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1951 for splitting the atomic nucleus, and was instrumental in the development of nuclea ...

and Ernest Walton

Ernest Thomas Sinton Walton (6 October 1903 – 25 June 1995) was an Irish physicist and Nobel laureate. He is best known for his work with John Cockcroft to construct one of the earliest types of particle accelerator, the Cockcroft–Walton ...

split lithium

Lithium (from el, λίθος, lithos, lit=stone) is a chemical element with the symbol Li and atomic number 3. It is a soft, silvery-white alkali metal. Under standard conditions, it is the least dense metal and the least dense solid ...

atoms with accelerated protons. Enrico Fermi and his team in Rome conducted experiments involving the bombardment of elements by slow neutrons, which produced heavier elements and isotope

Isotopes are two or more types of atoms that have the same atomic number (number of protons in their nuclei) and position in the periodic table (and hence belong to the same chemical element), and that differ in nucleon numbers (mass numb ...

s. Then, in December 1938, Otto Hahn

Otto Hahn (; 8 March 1879 – 28 July 1968) was a German chemist who was a pioneer in the fields of radioactivity and radiochemistry. He is referred to as the father of nuclear chemistry and father of nuclear fission. Hahn and Lise Meitner ...

and Fritz Strassmann

Friedrich Wilhelm Strassmann (; 22 February 1902 – 22 April 1980) was a German chemist who, with Otto Hahn in December 1938, identified the element barium as a product of the bombardment of uranium with neutrons. Their observation was the ke ...

at Hahn's laboratory in Berlin-Dahlem

Dahlem ( or ) is a locality of the Steglitz-Zehlendorf borough in southwestern Berlin. Until Berlin's 2001 administrative reform it was a part of the former borough of Zehlendorf. It is located between the mansion settlements of Grunewald and ...

bombarded uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weak ...

with slowed neutrons, and discovered that barium had been produced, and therefore that the uranium atomic nucleus

The atomic nucleus is the small, dense region consisting of protons and neutrons at the center of an atom, discovered in 1911 by Ernest Rutherford based on the 1909 Geiger–Marsden gold foil experiment. After the discovery of the neutron ...

had been split. Hahn wrote to his colleague Lise Meitner, who, with her nephew Otto Robert Frisch

Otto Robert Frisch FRS (1 October 1904 – 22 September 1979) was an Austrian-born British physicist who worked on nuclear physics. With Lise Meitner he advanced the first theoretical explanation of nuclear fission (coining the term) and firs ...

, developed a theoretical justification which they published in ''Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are ...

'' in 1939. This phenomenon was a new type of nuclear disintegration, and was more powerful than any seen before. Frisch and Meitner calculated that the energy released by each disintegration was approximately 200,000,000 electron volt

In physics, an electronvolt (symbol eV, also written electron-volt and electron volt) is the measure of an amount of kinetic energy gained by a single electron accelerating from rest through an electric potential difference of one volt in vacuum ...

s. By analogy with the division of biological cells, they named the process " fission".

Paris Group

This was followed up by a group of scientists at theCollège de France

The Collège de France (), formerly known as the ''Collège Royal'' or as the ''Collège impérial'' founded in 1530 by François I, is a higher education and research establishment ('' grand établissement'') in France. It is located in Paris n ...

in Paris: Frédéric Joliot-Curie

Jean Frédéric Joliot-Curie (; ; 19 March 1900 – 14 August 1958) was a French physicist and husband of Irène Joliot-Curie, with whom he was jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1935 for their discovery of Induced radioactivity. T ...

, Hans von Halban

Hans Heinrich von Halban (24 January 1908 – 28 November 1964) was a French physicist, of Austrian- Jewish descent.

Family

He was descended on his father's side from Polish Jews, who left Kraków for Vienna in the 1850s. His grandfather, Hei ...

, Lew Kowarski

Lew Kowarski (10 February 1907, Saint Petersburg – 30 July 1979, Geneva) was a naturalized French physicist. He was a lesser-known but important contributor to nuclear science.

Early life

Lew Kowarski was born in Saint Petersburg to Nicholas K ...

, and Francis Perrin. In February 1939, the Paris Group showed that when fission occurs in uranium, two or three extra neutrons are given off. This important observation suggested a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction might be possible. The term " atomic bomb" was already familiar to the British public through the writings of H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells"Wells, H. G."

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

In Britain, a number of scientists considered whether an atomic bomb was practical. At the

In Britain, a number of scientists considered whether an atomic bomb was practical. At the  At Birmingham, Oliphant's team had reached a different conclusion. Oliphant had delegated the task to two German refugee scientists,

At Birmingham, Oliphant's team had reached a different conclusion. Oliphant had delegated the task to two German refugee scientists,

Four universities provided the locations where the experiments were taking place. The laboratory at the University of Birmingham was responsible for all the theoretical work, such as what size of critical mass was needed for an explosion. It was run by Peierls, with the help of fellow German refugee scientist Klaus Fuchs. The laboratories at the University of Liverpool and the

Four universities provided the locations where the experiments were taking place. The laboratory at the University of Birmingham was responsible for all the theoretical work, such as what size of critical mass was needed for an explosion. It was run by Peierls, with the help of fellow German refugee scientist Klaus Fuchs. The laboratories at the University of Liverpool and the

When Moon examined the suggestion that gaseous thermal diffusion be the method of choice to the MAUD committee, there was no agreement to move forward with it. The committee consulted with Peierls and Simon over the separation method and concluded that "ordinary" gaseous diffusion was the best method to pursue. This relies on Graham's Law, the fact that the gases diffuse through porous materials at rates determined by their molecular weight.

When Moon examined the suggestion that gaseous thermal diffusion be the method of choice to the MAUD committee, there was no agreement to move forward with it. The committee consulted with Peierls and Simon over the separation method and concluded that "ordinary" gaseous diffusion was the best method to pursue. This relies on Graham's Law, the fact that the gases diffuse through porous materials at rates determined by their molecular weight.

Halban's heavy water team from France continued its slow neutron research at Cambridge University; but the project was given a low priority since it was not considered relevant to bomb making. It suddenly acquired military significance when it was realised that it provided the route to plutonium. The British Government wanted the Cambridge team to be relocated to North America, in proximity to the raw materials it required, and where the American research was being done. But Sir John Anderson wanted the British team to retain its own identity, and was concerned that since the Americans were working on

Halban's heavy water team from France continued its slow neutron research at Cambridge University; but the project was given a low priority since it was not considered relevant to bomb making. It suddenly acquired military significance when it was realised that it provided the route to plutonium. The British Government wanted the Cambridge team to be relocated to North America, in proximity to the raw materials it required, and where the American research was being done. But Sir John Anderson wanted the British team to retain its own identity, and was concerned that since the Americans were working on

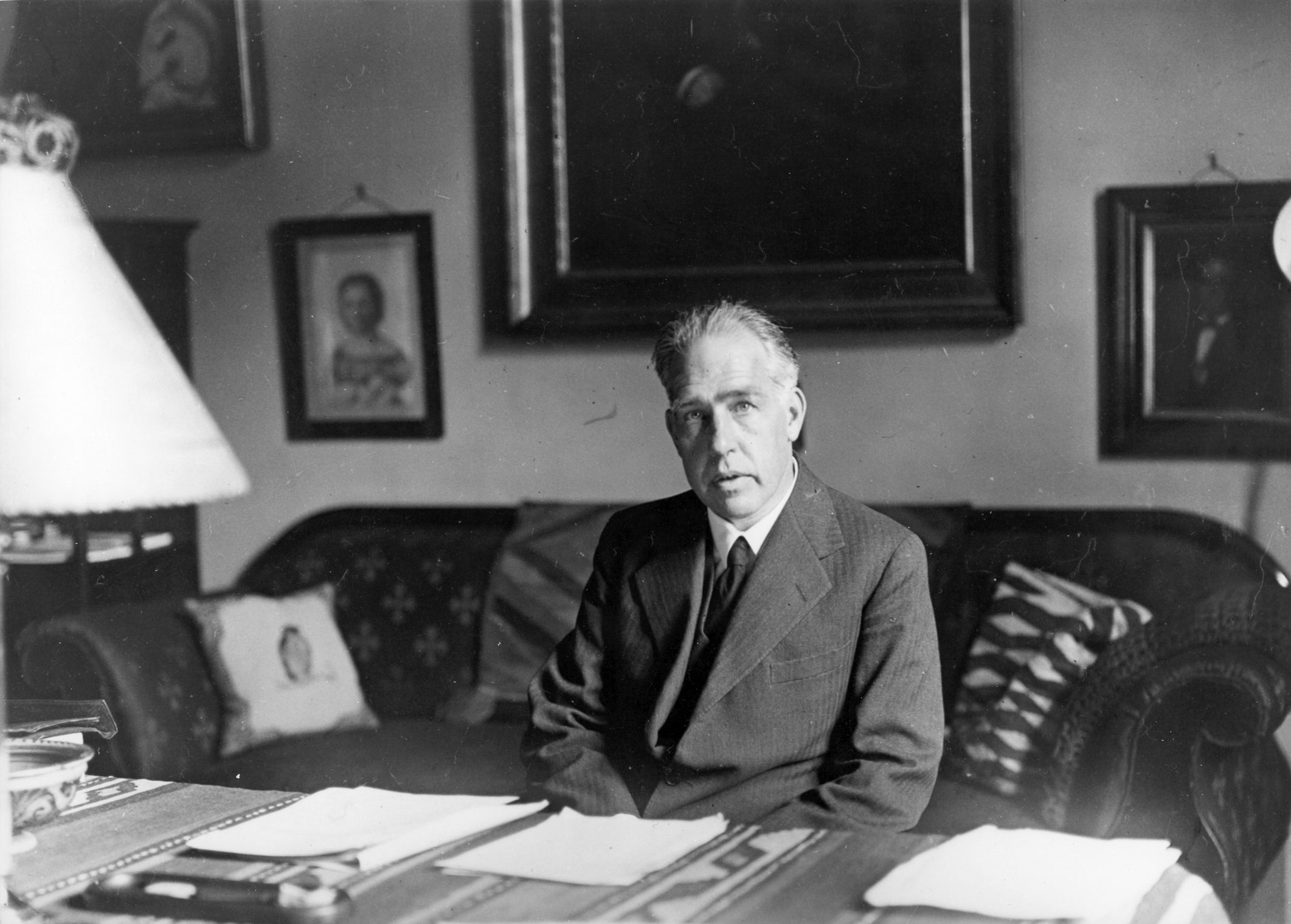

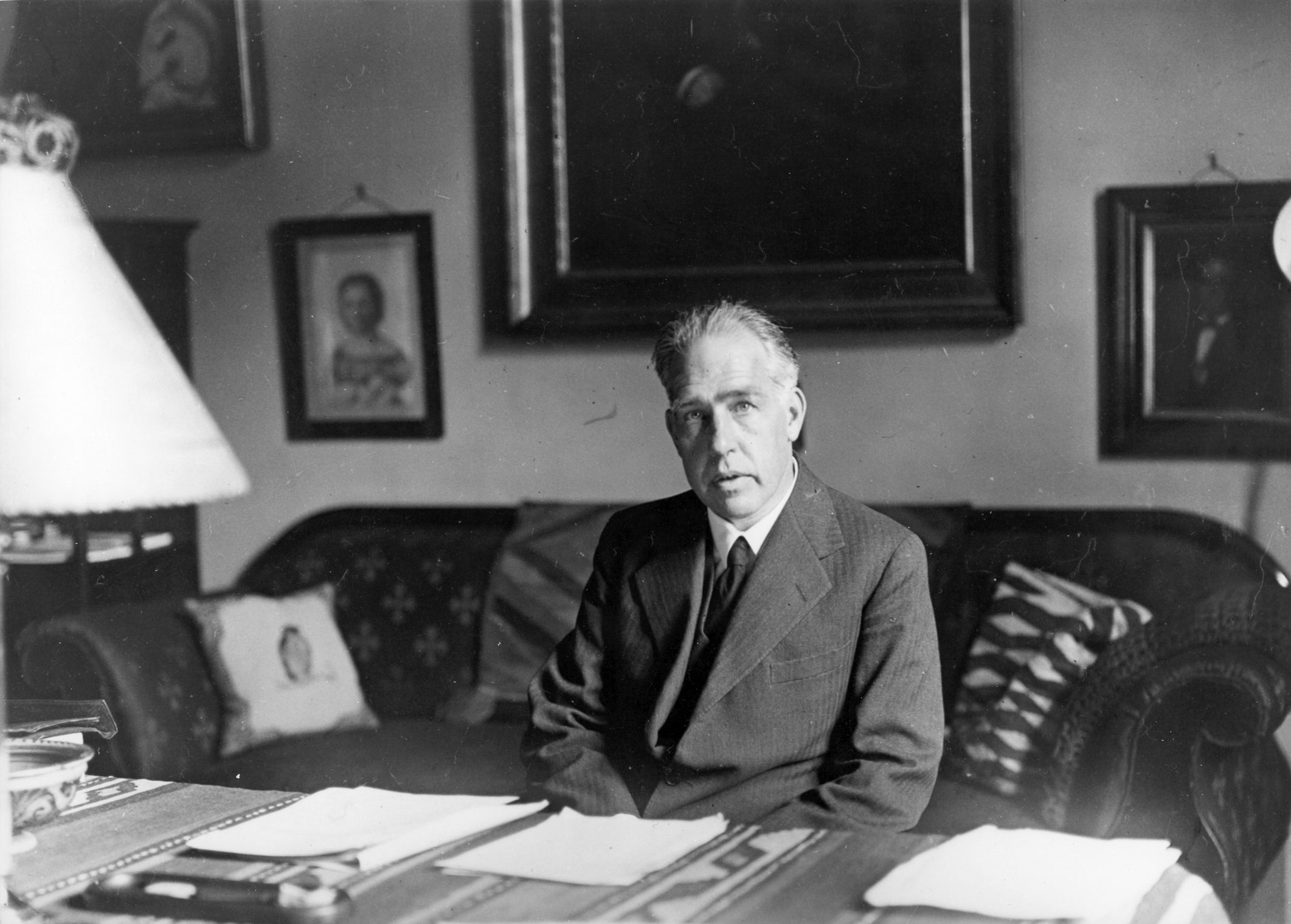

Sir John Anderson was eager to invite Niels Bohr to the Tube Alloys project because he was a world-famous scientist who would not only contribute his expertise to the project, but also help the British government gain leverage in dealings with the Manhattan Project.

In September 1943, word reached Bohr in Denmark that the Nazis considered his family to be Jewish, and that they were in danger of being arrested. The Danish resistance helped Bohr and his wife escape by sea to Sweden on 29 September 1943. When the news of Bohr's escape reached Britain, Lord Cherwell sent a telegram asking Bohr to come to Britain. Bohr arrived in Scotland on 6 October in a de Havilland Mosquito operated by the

Sir John Anderson was eager to invite Niels Bohr to the Tube Alloys project because he was a world-famous scientist who would not only contribute his expertise to the project, but also help the British government gain leverage in dealings with the Manhattan Project.

In September 1943, word reached Bohr in Denmark that the Nazis considered his family to be Jewish, and that they were in danger of being arrested. The Danish resistance helped Bohr and his wife escape by sea to Sweden on 29 September 1943. When the news of Bohr's escape reached Britain, Lord Cherwell sent a telegram asking Bohr to come to Britain. Bohr arrived in Scotland on 6 October in a de Havilland Mosquito operated by the

The MAUD Committee reports urged the co-operation with the United States should be continued in the research of nuclear fission. Charles C. Lauritsen, a Caltech physicist working at the

The MAUD Committee reports urged the co-operation with the United States should be continued in the research of nuclear fission. Charles C. Lauritsen, a Caltech physicist working at the

With this dispute settled collaboration could once again take place. Chadwick wanted to involve as many British scientists as possible so long as Groves accepted them. Chadwick's first choice, Joseph Rotblat refused to give up his Polish citizenship. Chadwick then turned to Otto Frisch, who to Chadwick's surprise accepted becoming a British citizen right away and began the screening process so he could travel to America. Chadwick spent the first few weeks of November 1943 acquiring a clear picture of the extensive Manhattan Project. He realised the scale of such sites as Oak Ridge, Tennessee, which was the new headquarters of the project, and could safely conclude that without similar industrial site being found in Germany the chances of the Nazi atomic bomb project being successful was very low.

With Chadwick involved the main goal was to show that the Quebec Agreement was a success. It was Britain's duty to co-operate to the fullest and speed along the process. Chadwick used this opportunity to give as many young British scientists experience as possible so they might carry that experience to post-war Britain. He eventually convinced Groves of Rotblat's integrity to the cause, and this led to Rotblat being accepted to the Manhattan Project without renouncing his nationality. Rotblat had been left in charge of the Tube Alloys research, and brought with him the results obtained since Chadwick had left.

The Montreal team in Canada depended on the Americans for heavy water from the US heavy water plant in

With this dispute settled collaboration could once again take place. Chadwick wanted to involve as many British scientists as possible so long as Groves accepted them. Chadwick's first choice, Joseph Rotblat refused to give up his Polish citizenship. Chadwick then turned to Otto Frisch, who to Chadwick's surprise accepted becoming a British citizen right away and began the screening process so he could travel to America. Chadwick spent the first few weeks of November 1943 acquiring a clear picture of the extensive Manhattan Project. He realised the scale of such sites as Oak Ridge, Tennessee, which was the new headquarters of the project, and could safely conclude that without similar industrial site being found in Germany the chances of the Nazi atomic bomb project being successful was very low.

With Chadwick involved the main goal was to show that the Quebec Agreement was a success. It was Britain's duty to co-operate to the fullest and speed along the process. Chadwick used this opportunity to give as many young British scientists experience as possible so they might carry that experience to post-war Britain. He eventually convinced Groves of Rotblat's integrity to the cause, and this led to Rotblat being accepted to the Manhattan Project without renouncing his nationality. Rotblat had been left in charge of the Tube Alloys research, and brought with him the results obtained since Chadwick had left.

The Montreal team in Canada depended on the Americans for heavy water from the US heavy water plant in

With the end of the war the Special Relationship between Britain and the United States "became very much less special". Roosevelt died on 12 April 1945, and the Hyde Park Agreement was not binding on subsequent administrations. In fact, it was physically lost: when Wilson raised the matter in a Combined Policy Committee meeting in June, the American copy could not be found. The British sent Stimson a photocopy on 18 July 1945. Even then, Groves questioned the document's authenticity until the American copy was located years later in the papers of Vice Admiral Wilson Brown Jr., Roosevelt's naval aide, apparently misfiled by someone unaware of what Tube Alloys was—who thought it had something to do with naval guns.

The British government had trusted that America would share nuclear technology, which the British saw as a joint discovery. On 9 November 1945, Mackenzie King and the Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, went to Washington, D.C., to confer with President

With the end of the war the Special Relationship between Britain and the United States "became very much less special". Roosevelt died on 12 April 1945, and the Hyde Park Agreement was not binding on subsequent administrations. In fact, it was physically lost: when Wilson raised the matter in a Combined Policy Committee meeting in June, the American copy could not be found. The British sent Stimson a photocopy on 18 July 1945. Even then, Groves questioned the document's authenticity until the American copy was located years later in the papers of Vice Admiral Wilson Brown Jr., Roosevelt's naval aide, apparently misfiled by someone unaware of what Tube Alloys was—who thought it had something to do with naval guns.

The British government had trusted that America would share nuclear technology, which the British saw as a joint discovery. On 9 November 1945, Mackenzie King and the Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, went to Washington, D.C., to confer with President

Minutes and memoranda of Tube Alloys Consultative Council, January 1942- April 1945

{{portal bar, Canada, History of Science, Politics, Nuclear technology, United Kingdom, World War II Nuclear history of the United Kingdom Code names Secret military programs 1942 establishments in the United Kingdom 1952 disestablishments Science and technology during World War II Military history of the United Kingdom during World War II

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

The World Set Free

''The World Set Free'' is a novel written in 1913 and published in 1914 by H. G. Wells. The book is based on a prediction of a more destructive and uncontrollable sort of weapon than the world has yet seen. It had appeared first in serialised ...

''. It was immediately apparent to many scientists that, in theory at least, an extremely powerful explosive could be created, although most still considered an atomic bomb was an impossibility. Perrin defined a critical mass

In nuclear engineering, a critical mass is the smallest amount of fissile material needed for a sustained nuclear chain reaction. The critical mass of a fissionable material depends upon its nuclear properties (specifically, its nuclear fi ...

of uranium to be the smallest amount that could sustain a chain reaction. The neutrons used to cause fission in uranium are considered slow neutrons, but when neutrons are released during a fission reaction they are released as fast neutrons which have much more speed and energy. Thus, in order to create a sustained chain reaction, there existed a need for a neutron moderator to contain and slow the fast neutrons until they reached a usable energy level. The Collège de France found that both water and graphite

Graphite () is a crystalline form of the element carbon. It consists of stacked layers of graphene. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable form of carbon under standard conditions. Synthetic and natural graphite are consumed on lar ...

could be used as acceptable moderators.

Early in 1940, the Paris Group decided on theoretical grounds that heavy water would be an ideal moderator for how they intended to use it. They asked the French Minister of Armaments to obtain as much heavy water as possible from the only source, the large Norsk Hydro

Norsk Hydro ASA (often referred to as just ''Hydro'') is a Norwegian aluminium and renewable energy company, headquartered in Oslo. It is one of the largest aluminium companies worldwide. It has operations in some 50 countries around the world a ...

hydroelectric station

Hydroelectricity, or hydroelectric power, is electricity generated from hydropower (water power). Hydropower supplies one sixth of the world's electricity, almost 4500 TWh in 2020, which is more than all other renewable sources combined an ...

at Vemork

Vemork is a hydroelectric power plant outside Rjukan in Tinn, Norway. The plant was built by Norsk Hydro and opened in 1911, its main purpose being to fix nitrogen for the production of fertilizer. At opening, it was the world's largest power pl ...

in Norway. The French then discovered Germany had already offered to purchase the entire stock of Norwegian heavy water, indicating that Germany might also be researching an atomic bomb. The French told the Norwegian government of the possible military significance of heavy water. Norway gave the entire stock of to a ''Deuxième Bureau

The Deuxième Bureau de l'État-major général ("Second Bureau of the General Staff") was France's external military intelligence agency from 1871 to 1940. It was dissolved together with the Third Republic upon the armistice with Germany. Howeve ...

'' agent, who secretly brought it to France just before Germany invaded Norway in April 1940. On 19 June 1940, following the German invasion of France

France has been invaded on numerous occasions, by foreign powers or rival French governments; there have also been unimplemented invasion plans.

* the 1746 War of the Austrian Succession, Austria-Italian forces supported by the British navy attemp ...

, it was shipped to England by the Earl of Suffolk

Earl of Suffolk is a title which has been created four times in the Peerage of England. The first creation, in tandem with the creation of the title of Earl of Norfolk, came before 1069 in favour of Ralph the Staller; but the title was forfe ...

and Major Ardale Vautier Golding aboard the steamer . The heavy water, valued at £22,000, was initially kept at HM Prison Wormwood Scrubs

HM Prison Wormwood Scrubs (nicknamed "The Scrubs") is a Category B men's local prison, located opposite Hammersmith Hospital and W12 Conferences on Du Cane Road in the White City in West London, England. The prison is operated by His Majesty' ...

, and was later secretly stored in the library at Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a royal residence at Windsor in the English county of Berkshire. It is strongly associated with the English and succeeding British royal family, and embodies almost a millennium of architectural history.

The original c ...

. The Paris Group moved to Cambridge, with the exception of Joliot-Curie, who remained in France and became active in the French Resistance

The French Resistance (french: La Résistance) was a collection of organisations that fought the German occupation of France during World War II, Nazi occupation of France and the Collaborationism, collaborationist Vichy France, Vichy régim ...

.

Frisch–Peierls memorandum

In Britain, a number of scientists considered whether an atomic bomb was practical. At the

In Britain, a number of scientists considered whether an atomic bomb was practical. At the University of Liverpool

, mottoeng = These days of peace foster learning

, established = 1881 – University College Liverpool1884 – affiliated to the federal Victoria Universityhttp://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukla/2004/4 University of Manchester Act 200 ...

, Chadwick and the Polish refugee scientist Joseph Rotblat

Sir Joseph Rotblat (4 November 1908 – 31 August 2005) was a Polish and British physicist. During World War II he worked on Tube Alloys and the Manhattan Project, but left the Los Alamos Laboratory on grounds of conscience after it became ...

tackled the problem, but their calculations were inconclusive. At Cambridge, Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

laureates George Paget Thomson

Sir George Paget Thomson, FRS (; 3 May 189210 September 1975) was a British physicist and Nobel laureate in physics recognized for his discovery of the wave properties of the electron by electron diffraction.

Education and early life

Thomso ...

and William Lawrence Bragg

Sir William Lawrence Bragg, (31 March 1890 – 1 July 1971) was an Australian-born British physicist and X-ray crystallographer, discoverer (1912) of Bragg's law of X-ray diffraction, which is basic for the determination of crystal structu ...

wanted the government to take urgent action to acquire uranium ore

Uranium ore deposits are economically recoverable concentrations of uranium within the Earth's crust. Uranium is one of the more common elements in the Earth's crust, being 40 times more common than silver and 500 times more common than gold. It ...

. The main source of this was the Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (french: Congo belge, ; nl, Belgisch-Congo) was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960. The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Colo ...

, and they were worried that it could fall into German hands. Unsure as to how to go about this, they spoke to Sir William Spens, the master

Master or masters may refer to:

Ranks or titles

* Ascended master, a term used in the Theosophical religious tradition to refer to spiritually enlightened beings who in past incarnations were ordinary humans

*Grandmaster (chess), National Master ...

of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. In April 1939, he approached Sir Kenneth Pickthorn Sir Kenneth William Murray Pickthorn, 1st Baronet, PC (23 April 1892 – 12 November 1975) was a British academic and politician.

The eldest son of Charles Wright Pickthorn, master mariner, and Edith Maud Berkeley Murray, he was educated at Aldenh ...

, the local Member of Parliament, who took their concerns to the Secretary of the Committee for Imperial Defence

The Committee of Imperial Defence was an important ''ad hoc'' part of the Government of the United Kingdom and the British Empire from just after the Second Boer War until the start of the Second World War. It was responsible for research, and som ...

, Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

Hastings Ismay

Hastings Lionel Ismay, 1st Baron Ismay (21 June 1887 – 17 December 1965), was a diplomat and general in the British Indian Army who was the first Secretary General of NATO. He also was Winston Churchill's chief military assistant during the ...

. Ismay in turn asked Sir Henry Tizard

Sir Henry Thomas Tizard (23 August 1885 – 9 October 1959) was an English chemist, inventor and Rector of Imperial College, who developed the modern "octane rating" used to classify petrol, helped develop radar in World War II, and led the fir ...

for an opinion. Like many scientists, Tizard was sceptical of the likelihood of an atomic bomb being developed, reckoning the odds of success at 100,000 to 1.

Even at such long odds, the danger was sufficiently great to be taken seriously. Lord Chartfield, Minister for Coordination of Defence

The Minister for Co-ordination of Defence was a British Cabinet-level position established in 1936 to oversee and co-ordinate the rearmament of Britain's defences. It was abolished in 1940.

History

The position was established by Prime Minister ...

, checked with the Treasury

A treasury is either

*A government department related to finance and taxation, a finance ministry.

*A place or location where treasure, such as currency or precious items are kept. These can be state or royal property, church treasure or i ...

and Foreign Office, and found that the Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (french: Congo belge, ; nl, Belgisch-Congo) was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960. The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Colo ...

uranium was owned by the ''Union Minière du Haut Katanga

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

'' company, whose British vice president, Lord Stonehaven, arranged a meeting with the president of the company, Edgar Sengier

Edgar Edouard Bernard Sengier (9 October 1879 – 26 July 1963) was a Belgian mining engineer and director of the Union Minière du Haut Katanga mining company that operated in Belgian Congo during World War II.

Sengier is credited with ...

. Since ''Union Minière'' management were friendly towards Britain, it was not considered worthwhile to acquire the uranium immediately, but Tizard's Committee on the Scientific Survey of Air Defence was directed to continue the research into the feasibility of atomic bombs. Thomson, at Imperial College London, and Mark Oliphant

Sir Marcus Laurence Elwin Oliphant, (8 October 1901 – 14 July 2000) was an Australian physicist and humanitarian who played an important role in the first experimental demonstration of nuclear fusion and in the development of nuclear weapon ...

, an Australian physicist at the University of Birmingham

The University of Birmingham (informally Birmingham University) is a Public university, public research university located in Edgbaston, Birmingham, United Kingdom. It received its royal charter in 1900 as a successor to Queen's College, Birmingha ...

, were each tasked with carrying out a series of experiments on uranium. By February 1940, Thomson's team had failed to create a chain reaction in natural uranium, and he had decided it was not worth pursuing.

At Birmingham, Oliphant's team had reached a different conclusion. Oliphant had delegated the task to two German refugee scientists,

At Birmingham, Oliphant's team had reached a different conclusion. Oliphant had delegated the task to two German refugee scientists, Rudolf Peierls

Sir Rudolf Ernst Peierls, (; ; 5 June 1907 – 19 September 1995) was a German-born British physicist who played a major role in Tube Alloys, Britain's nuclear weapon programme, as well as the subsequent Manhattan Project, the combined Allie ...

and Otto Frisch, who could not work on Oliphant's radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, we ...

project because they were enemy alien

In customary international law, an enemy alien is any native, citizen, denizen or subject of any foreign nation or government with which a domestic nation or government is in conflict and who is liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured and ...

s and therefore lacked the necessary security clearance. Francis Perrin had calculated the critical mass of uranium to be about . He reckoned that if a neutron reflector

A neutron reflector is any material that reflects neutrons. This refers to elastic scattering rather than to a specular reflection. The material may be graphite, beryllium, steel, tungsten carbide, gold, or other materials. A neutron reflector ...

were placed around it, this might be reduced to . Peierls attempted to simplify the problem by using the fast neutrons produced by fission, thus omitting consideration of moderator. He too calculated the critical mass of a sphere of uranium in a theoretical paper written in 1939 to be "of the order of tons".

Peierls knew the importance of the size of the critical mass that would allow a chain reaction to take place and its practical significance. In the interior of a critical mass sphere, neutrons are spontaneously produced by the fissionable material. A very small portion of these neutrons are colliding with other nuclei, while a larger portion of the neutrons are escaping through the surface of the sphere. Peierls calculated the equilibrium of the system, where the number of neutrons being produced equalled the number escaping.

Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr (; 7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum theory, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922 ...

had theorised that the rare uranium-235

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exi ...

isotope, which makes up only about 0.7% of natural uranium, was primarily responsible for fission with fast neutrons, although this was not yet universally accepted. Frisch and Peierls were thus able to revise their initial estimate of critical mass needed for nuclear fission in uranium to be substantially less than previously assumed. They estimated a metallic sphere of uranium-235 with a radius of could suffice. This amount represented approximately of uranium-235. These results led to the Frisch–Peierls memorandum, which was the initial step in the development of the nuclear arms programme in Britain. This marked the beginning of an aggressive approach towards uranium enrichment and the development of an atomic bomb. They now began to investigate processes by which they could successfully separate the uranium isotope.

Oliphant took their findings to Tizard in his capacity as the chairman of the Committee for the Scientific Survey of Air Warfare (CSSAW). He in turn passed them to Thomson, to whom the CSSAW had delegated responsibility for uranium research. After discussions between Cockcroft, Oliphant and Thomson, CSSAW created the MAUD Committee to investigate further.

MAUD Committee

The MAUD Committee was founded in June 1940. The committee was originally a part of the Committee for the Scientific Survey of Air Defence, but later gained independence with the Ministry of Aircraft Production. The committee was initially named after its chairman, Thomson, but quickly exchanged this for a more unassuming name, the MAUD Committee. The name MAUD came to be in an unusual way. Shortly after Germany invaded Denmark, Bohr had sent a telegram to Frisch. The telegram ended with a strange line: "Tell Cockcroft and Maud Ray Kent". At first it was thought to be code regarding radium or other vital atomic-weapons-related information, hidden in an anagram. One suggestion was to replace the y with an i, producing "radium taken". When Bohr returned to England in 1943, it was discovered that the message was addressed to Bohr's housekeeper Maud Ray and Cockcroft. Maud Ray was from Kent. Thus the committee was named The MAUD Committee, the capitalisation representing a codename and not an acronym. Meetings were normally held in the offices of theRoyal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in London. In addition to Thomson, its original members were Chadwick, Cockcroft, Oliphant and Philip Moon, Patrick Blackett

Patrick Maynard Stuart Blackett, Baron Blackett (18 November 1897 – 13 July 1974) was a British experimental physicist known for his work on cloud chambers, cosmic rays, and paleomagnetism, winning the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1948. ...

, Charles Ellis and Norman Haworth

Sir Walter Norman Haworth FRS (19 March 1883 – 19 March 1950) was a British chemist best known for his groundbreaking work on ascorbic acid ( vitamin C) while working at the University of Birmingham. He received the 1937 Nobel Prize in Chem ...

.

Four universities provided the locations where the experiments were taking place. The laboratory at the University of Birmingham was responsible for all the theoretical work, such as what size of critical mass was needed for an explosion. It was run by Peierls, with the help of fellow German refugee scientist Klaus Fuchs. The laboratories at the University of Liverpool and the

Four universities provided the locations where the experiments were taking place. The laboratory at the University of Birmingham was responsible for all the theoretical work, such as what size of critical mass was needed for an explosion. It was run by Peierls, with the help of fellow German refugee scientist Klaus Fuchs. The laboratories at the University of Liverpool and the University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

experimented with different types of isotope separation. Chadwick's group at Liverpool dealt with thermal diffusion, which worked based on the principle that different isotopes of uranium diffuse at different speeds because of the equipartition theorem

In classical statistical mechanics, the equipartition theorem relates the temperature of a system to its average energies. The equipartition theorem is also known as the law of equipartition, equipartition of energy, or simply equipartition. T ...

. Franz Simon

Sir Francis Simon (2 July 1893 – 31 October 1956), was a German and later British physical chemist and physicist who devised the gaseous diffusion method, and confirmed its feasibility, of separating the isotope Uranium-235 and thus made a ...

's group at Oxford investigated the gaseous diffusion

Gaseous diffusion is a technology used to produce enriched uranium by forcing gaseous uranium hexafluoride (UF6) through semipermeable membranes. This produces a slight separation between the molecules containing uranium-235 (235U) and uranium-2 ...

of isotopes. This method works on the principle that at differing pressures uranium 235 would diffuse through a barrier faster than uranium 238. Eventually, the most promising method of separation was found to be gaseous diffusion. Egon Bretscher

Egon Bretscher CBE (1901–1973) was a Swiss-born British chemist and nuclear physicist and Head of the Nuclear Physics Division from 1948 to 1966 at the Atomic Energy Research Establishment, also known as Harwell Laboratory, in Harwell, United ...

and Norman Feather

Norman Feather FRS FRSE PRSE (16 November 1904 – 14 August 1978), was an English nuclear physicist. Feather and Egon Bretscher were working at the Cavendish Laboratory, Cambridge in 1940, when they proposed that the 239 isotope of element ...

's group at Cambridge investigated whether another element, now called plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibi ...

, could be used as an explosive compound. Because of the French scientists, Oxford also obtained the world's only supply of heavy water, which helped them theorise how uranium could be used for power.

The research from the MAUD committee was compiled in two reports, commonly known as the MAUD reports in July 1941. The first report, "Use of Uranium for a Bomb", discussed the feasibility of creating a super-bomb from uranium, which they now thought to be possible. The second, "Use of Uranium as a Source of Power" discussed the idea of using uranium as a source of power, not just a bomb. The MAUD Committee and report helped bring about the British nuclear programme, the Tube Alloys Project. Not only did it help start a nuclear project in Britain, it helped jump-start the American project. Without the help of the MAUD Committee the American programme, the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, would have started months behind. Instead they were able to begin thinking about how to create a bomb, not whether it was possible. Historian Margaret Gowing

Margaret Mary Gowing (), (26 April 1921 – 7 November 1998) was an English historian. She was involved with the production of several volumes of the officially sponsored ''History of the Second World War'', but was better known for her books ...

noted that "events that change a time scale by only a few months can nevertheless change history."

The MAUD reports were reviewed by the Defence Services Panel of the Scientific Advisory Committee. This was chaired by Lord Hankey, with its other members being Sir Edward Appleton, Sir Henry Dale, Alfred Egerton, Archibald Hill

Archibald Vivian Hill (26 September 1886 – 3 June 1977), known as A. V. Hill, was a British physiologist, one of the founders of the diverse disciplines of biophysics and operations research. He shared the 1922 Nobel Prize in Physiology or ...

and Edward Mellanby

Sir Edward Mellanby (8 April 1884 – 30 January 1955) was a British biochemist and nutritionist who discovered vitamin D and its role in preventing rickets in 1919.

Education

Mellanby was born in West Hartlepool, the son of a shipyard owner, ...

. The panel held seven meetings in September 1941, and submitted its report to the Lord President of the Council, Sir John Anderson. At this point, it was feared that German scientists were attempting to provide their country with an atomic bomb, and thus Britain needed to finish theirs first. The report ultimately stated that if there were even a sliver of a chance that the bomb effort could produce a weapon with such power, then every effort should be made to make sure Britain did not fall behind. It recommended that while a pilot separation plant be built in Britain, the production facility should be built in Canada. The Defence Services Panel submitted its report on 24 September 1941, but by this time the final decision had already been taken. Lord Cherwell had taken the matter to the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, who became the first national leader to approve a nuclear weapons programme on 30 August 1941. The Chiefs of Staff Committee

The Chiefs of Staff Committee (CSC) is composed of the most senior military personnel in the British Armed Forces who advise on operational military matters and the preparation and conduct of military operations. The committee consists of the C ...

supported the decision.

Tube Alloys organisation

A directorate of Tube Alloys was established as part of Appleton'sDepartment of Scientific and Industrial Research Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, abbreviated DSIR was the name of several British Empire organisations founded after the 1923 Imperial Conference to foster intra-Empire trade and development.

* Department of Scientific and Industria ...

, and Wallace Akers

Sir Wallace Alan Akers (9 September 1888 – 1 November 1954) was a British chemist and industrialist. Beginning his academic career at Oxford he specialized in physical chemistry. During the Second World War, he was the director of the Tube Al ...

, the research director of Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI), was chosen as its head. Anderson and Akers came up with the name Tube Alloys. It was deliberately chosen to be meaningless, "with a specious air of probability about it". An advisory committee known as the Tube Alloys Consultative Council was created to oversee its work, chaired by Anderson, with its other members being Lord Hankey, Lord Cherwell, Sir Edward Appleton and Sir Henry Dale. This handled policy matters. To deal with technical issues, a Technical Committee was created with Akers as chairman, and Chadwick, Simon, Halban, Peierls, and a senior ICI official Ronald Slade as its original members, with Michael Perrin as its secretary. It was later joined by Charles Galton Darwin, Cockcroft, Oliphant and Feather.

Isotopic separation

The biggest problem faced by the MAUD Committee was to find a way to separate the 0.7% of uranium-235 from the 99.3% of uranium-238. This is difficult because the two types of uranium are chemically identical. Separation (uranium enrichment

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (238 ...

) would have to be achieved at a large scale. At Cambridge, Eric Rideal

Sir Eric Keightley Rideal, (11 April 1890 – 25 September 1974)Rideal, Sir Eric Keight ...

and his team investigated using a gas centrifuge

A gas centrifuge is a device that performs isotope separation of gases. A centrifuge relies on the principles of centrifugal force accelerating molecules so that particles of different masses are physically separated in a gradient along the radiu ...

. Frisch chose to perform gaseous thermal diffusion using Clusius tubes because it seemed the simplest method. Frisch's calculations showed there would need to be 100,000 Clusius tubes to extract the desired separation amount. Peierls turned to Franz Simon, who preferred to find a method more suitable for mass production.

When Moon examined the suggestion that gaseous thermal diffusion be the method of choice to the MAUD committee, there was no agreement to move forward with it. The committee consulted with Peierls and Simon over the separation method and concluded that "ordinary" gaseous diffusion was the best method to pursue. This relies on Graham's Law, the fact that the gases diffuse through porous materials at rates determined by their molecular weight.

When Moon examined the suggestion that gaseous thermal diffusion be the method of choice to the MAUD committee, there was no agreement to move forward with it. The committee consulted with Peierls and Simon over the separation method and concluded that "ordinary" gaseous diffusion was the best method to pursue. This relies on Graham's Law, the fact that the gases diffuse through porous materials at rates determined by their molecular weight. Francis William Aston

Francis William Aston FRS (1 September 1877 – 20 November 1945) was a British chemist and physicist who won the 1922 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his discovery, by means of his mass spectrograph, of isotopes in many non-radioactive elements a ...

applied this method in 1913 when he separated two isotopes of neon by diffusing a sample thousands of times through a pipe clay. Thick materials like pipe clay proved too slow to be efficient on an industry scale. Simon proposed using a metal foil punctured with millions of microscopic holes would allow the separation process to move faster. He estimated that a plant that separated of uranium-235 from natural uranium per day would cost about £5,000,000 to build, and £1,500,000 per year to run, in which time it would consume £2,000,000 of uranium and other raw materials. The MAUD Committee realised an atomic bomb was not just feasible, but inevitable.

In 1941, Frisch moved to London to work with Chadwick and his cyclotron. Frisch built a Clusius tube there to study the properties of uranium hexafluoride. Frisch and Chadwick discovered it is one of the gases for which the Clusius method will not work. This was only a minor setback because Simon was already in progress of establishing the alternative method of separation through ordinary gaseous diffusion.

The chemical problems of producing gaseous compounds of uranium and pure uranium metal were studied at the University of Birmingham and by ICI. Michael Clapham, who at the time was working on print technology at the Kynoch Works in Aston in Birmingham, carried out early experiments with uranium production processes. Philip Baxter

Sir John Philip Baxter (7 May 1905 – 5 September 1989) was a British chemical engineer. He was the second director of the University of New South Wales from 1953, continuing as vice-chancellor when the position's title was changed in 1955. Un ...

from ICI, where he had experience working with fluorine compounds, made the first small batch of gaseous uranium hexafluoride for Chadwick in 1940. ICI received a formal £5,000 contract in December 1940 to make of this vital material for the future work. The prototype gaseous diffusion equipment itself was manufactured by Metropolitan-Vickers

Metropolitan-Vickers, Metrovick, or Metrovicks, was a British heavy electrical engineering company of the early-to-mid 20th century formerly known as British Westinghouse. Highly diversified, it was particularly well known for its industrial el ...

(MetroVick) at Trafford Park, Manchester, at a cost of £150,000 for four units. They were installed at the M. S. Factory located in a valley near Rhydymwyn

Rhydymwyn (the name in Welsh means 'Ford of the Ore' and takes its placename from the ford across the River Alyn now replaced by a small iron bridge) is a village in Flintshire, Wales, located in the upper Alyn valley. Once a district of Mold, i ...

, in Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

; M. S. stood for the Ministry of Supply. The building used was known as P6 and test equipment was installed. These units were tested by a team of about seventy under the guidance of Peierls and Fuchs. The results of the experiments led to the building of the gaseous diffusion factory at Capenhurst, Cheshire. ICI pilot plants for producing of pure uranium metal and of uranium hexafluoride per day commenced operation in Widnes

Widnes ( ) is an industrial town in the Borough of Halton, Cheshire, England, which at the 2011 census had a population of 61,464.

Historically in Lancashire, it is on the northern bank of the River Mersey where the estuary narrows to form th ...

in mid-1943.

Plutonium

The breakthrough with plutonium was by Bretscher and Norman Feather at the Cavendish Laboratory. They realised that a slow neutron reactor fuelled with uranium would theoretically produce substantial amounts ofplutonium-239

Plutonium-239 (239Pu or Pu-239) is an isotope of plutonium. Plutonium-239 is the primary fissile isotope used for the production of nuclear weapons, although uranium-235 is also used for that purpose. Plutonium-239 is also one of the three mai ...

as a by-product. This is because uranium-238 absorbs slow neutron

The neutron detection temperature, also called the neutron energy, indicates a free neutron's kinetic energy, usually given in electron volts. The term ''temperature'' is used, since hot, thermal and cold neutrons are moderated in a medium with ...

s and forms a short-lived new isotope, uranium-239

Uranium (92U) is a naturally occurring radioactive element that has no stable isotope. It has two primordial isotopes, uranium-238 and uranium-235, that have long half-lives and are found in appreciable quantity in the Earth's crust. The decay ...

. The new isotope's nucleus rapidly emits an electron through beta decay

In nuclear physics, beta decay (β-decay) is a type of radioactive decay in which a beta particle (fast energetic electron or positron) is emitted from an atomic nucleus, transforming the original nuclide to an isobar of that nuclide. For ...

producing a new element with an atomic mass

The atomic mass (''m''a or ''m'') is the mass of an atom. Although the SI unit of mass is the kilogram (symbol: kg), atomic mass is often expressed in the non-SI unit dalton (symbol: Da) – equivalently, unified atomic mass unit (u). 1&nb ...

of 239 and an atomic number

The atomic number or nuclear charge number (symbol ''Z'') of a chemical element is the charge number of an atomic nucleus. For ordinary nuclei, this is equal to the proton number (''n''p) or the number of protons found in the nucleus of every ...

of 93. This element's nucleus also emits an electron and becomes a new element with an atomic number 94 and a much greater half-life. Bretscher and Feather showed theoretically feasible grounds that element 94 would be fissile

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material capable of sustaining a nuclear fission chain reaction. By definition, fissile material can sustain a chain reaction with neutrons of thermal energy. The predominant neutron energy may be t ...

readily split by both slow and fast neutrons with the added advantage of being chemically different from uranium.

This new development was also confirmed in independent work by Edwin M. McMillan and Philip Abelson

Philip, also Phillip, is a male given name, derived from the Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominent Philips who popularize ...

at Berkeley Radiation Laboratory also in 1940. Nicholas Kemmer

Nicholas Kemmer (7 December 1911 – 21 October 1998) was a Russian-born nuclear physicist working in Britain, who played an integral and leading edge role in United Kingdom's nuclear programme, and was known as a mentor of Abdus Salam – a N ...

of the Cambridge team proposed the names neptunium

Neptunium is a chemical element with the symbol Np and atomic number 93. A radioactive actinide metal, neptunium is the first transuranic element. Its position in the periodic table just after uranium, named after the planet Uranus, led to it bein ...

for the new element 93 and plutonium for 94 by analogy with the outer planets Neptune and Pluto beyond Uranus (uranium being element 92). The Americans fortuitously suggested the same names. The production and identification of the first sample of plutonium in 1941 is generally credited to Glenn Seaborg

Glenn Theodore Seaborg (; April 19, 1912February 25, 1999) was an American chemist whose involvement in the synthesis, discovery and investigation of ten transuranium elements earned him a share of the 1951 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. His work i ...

, using a cyclotron

A cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator invented by Ernest O. Lawrence in 1929–1930 at the University of California, Berkeley, and patented in 1932. Lawrence, Ernest O. ''Method and apparatus for the acceleration of ions'', filed: Jan ...

rather than a reactor at the University of California

The University of California (UC) is a public land-grant research university system in the U.S. state of California. The system is composed of the campuses at Berkeley, Davis, Irvine, Los Angeles, Merced, Riverside, San Diego, San Franci ...

. In 1941, neither team knew of the existence of the other.

Chadwick voiced concerns about the need for such pure plutonium to make a feasible bomb. He also suspected the gun method of detonation for a plutonium bomb would lead to premature detonations due to impurities. After Chadwick met Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist. A professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley, Oppenheimer was the wartime head of the Los Alamos Laboratory and is often ...

at the Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and operated by the University of California during World War II. Its mission was to design and build the first atomic bombs. Ro ...

in 1943, he learned of a proposed bomb design which they were calling an implosion. The sub-critical mass of plutonium was supposed to be surrounded by explosives arranged to detonate simultaneously. This would cause the plutonium core to be compressed and become supercritical. The core would be surrounded by a depleted uranium tamper which would reflect the neutrons back into the reaction, and contribute to the explosion by fissioning itself. This design solved Chadwick's worries about purity because it did not require the level needed for the gun-type fission weapon

Gun-type fission weapons are fission-based nuclear weapons whose design assembles their fissile material into a supercritical mass by the use of the "gun" method: shooting one piece of sub-critical material into another. Although this is someti ...

. The biggest problem with this method was creating the explosive lens

An explosive lens—as used, for example, in nuclear weapons—is a highly specialized shaped charge. In general, it is a device composed of several explosive charges. These charges are arranged and formed with the intent to control the shape ...

es. Chadwick took this information with him and described the method to Oliphant who then took it with him to England.

Montreal Laboratory

Halban's heavy water team from France continued its slow neutron research at Cambridge University; but the project was given a low priority since it was not considered relevant to bomb making. It suddenly acquired military significance when it was realised that it provided the route to plutonium. The British Government wanted the Cambridge team to be relocated to North America, in proximity to the raw materials it required, and where the American research was being done. But Sir John Anderson wanted the British team to retain its own identity, and was concerned that since the Americans were working on

Halban's heavy water team from France continued its slow neutron research at Cambridge University; but the project was given a low priority since it was not considered relevant to bomb making. It suddenly acquired military significance when it was realised that it provided the route to plutonium. The British Government wanted the Cambridge team to be relocated to North America, in proximity to the raw materials it required, and where the American research was being done. But Sir John Anderson wanted the British team to retain its own identity, and was concerned that since the Americans were working on nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat fr ...

designs using nuclear graphite

Nuclear graphite is any grade of graphite, usually synthetic graphite, manufactured for use as a moderator or reflector within a nuclear reactor. Graphite is an important material for the construction of both historical and modern nuclear reactor ...

instead of heavy water as a neutron moderator, that team might not receive a fair share of resources. The Americans had their own concerns, particularly about security, since only one of the six senior scientists in the group was British. They also had concerns about patent rights; that the French team would attempt to patent nuclear technology based on the pre-war work. As a compromise, Thomson suggested relocating the team to Canada.

The Canadian government was approached, and Jack Mackenzie

Chalmers Jack Mackenzie, (July 10, 1888 – February 26, 1984) was a Canadian civil engineer, chancellor of Carleton University, president of the National Research Council, first president of Atomic Energy of Canada Limited, first president ...

, the president of the National Research Council of Canada

The National Research Council Canada (NRC; french: Conseil national de recherches Canada) is the primary national agency of the Government of Canada dedicated to science and technology research & development. It is the largest federal research ...

, immediately welcomed and supported the proposal. The costs and salaries would be divided between the British and Canadian governments, but the British share would come from a billion dollar war gift from Canada. The first eight staff arrived in Montreal at the end of 1942, and occupied a house belonging to McGill University

McGill University (french: link=no, Université McGill) is an English-language public research university located in Montreal, Quebec

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous ...

. Three months later they moved into a area in a new building at the University of Montreal

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, th ...

. The laboratory grew quickly to over 300 staff; about half were Canadians recruited by George Laurence. A subgroup of theoreticians was recruited and headed by a Czechoslovak physicist, George Placzek. Placzek proved to be a very capable group leader, and was generally regarded as the only member of the staff with the stature of the highest scientific rank and with close personal contacts with many key physicists involved in the Manhattan project. Friedrich Paneth became head of the chemistry division, and Pierre Auger of the experimental physics division. Von Halban was the director of the laboratory, but he proved to be an unfortunate choice as he was a poor administrator, and did not work well with the National Research Council of Canada. The Americans saw him as a security risk, and objected to the French atomic patents claimed by the Paris Group (in association with ICI).

Niels Bohr's contribution to Tube Alloys

Sir John Anderson was eager to invite Niels Bohr to the Tube Alloys project because he was a world-famous scientist who would not only contribute his expertise to the project, but also help the British government gain leverage in dealings with the Manhattan Project.

In September 1943, word reached Bohr in Denmark that the Nazis considered his family to be Jewish, and that they were in danger of being arrested. The Danish resistance helped Bohr and his wife escape by sea to Sweden on 29 September 1943. When the news of Bohr's escape reached Britain, Lord Cherwell sent a telegram asking Bohr to come to Britain. Bohr arrived in Scotland on 6 October in a de Havilland Mosquito operated by the

Sir John Anderson was eager to invite Niels Bohr to the Tube Alloys project because he was a world-famous scientist who would not only contribute his expertise to the project, but also help the British government gain leverage in dealings with the Manhattan Project.

In September 1943, word reached Bohr in Denmark that the Nazis considered his family to be Jewish, and that they were in danger of being arrested. The Danish resistance helped Bohr and his wife escape by sea to Sweden on 29 September 1943. When the news of Bohr's escape reached Britain, Lord Cherwell sent a telegram asking Bohr to come to Britain. Bohr arrived in Scotland on 6 October in a de Havilland Mosquito operated by the British Overseas Airways Corporation

British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) was the British state-owned airline created in 1939 by the merger of Imperial Airways and British Airways Ltd. It continued operating overseas services throughout World War II. After the pass ...

(BOAC).

At the invitation of the director of the Manhattan Project, Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

Leslie R. Groves Jr.

Lieutenant general (United States), Lieutenant General Leslie Richard Groves Jr. (17 August 1896 – 13 July 1970) was a United States Army Corps of Engineers Officer (armed forces), officer who oversaw the construction of the Pentagon and di ...

, Bohr visited the Manhattan Project sites in November 1943. Groves offered Bohr substantial pay, but Bohr initially refused the offer because he wanted to make sure the relationship between the United States and Great Britain remained a real co-operative partnership. In December 1943, after a meeting with Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

, Bohr and his son Aage

Aage is a Danish masculine given name and a less common spelling of the Norwegian given name Åge. Variants include the Swedish name Åke. People with the name Aage include:

* Aage Bendixen (1887–1973), Danish actor

* Aage Berntsen (1885–195 ...

committed to working on the Manhattan Project. Bohr made a substantial contribution to the atomic bomb development effort. He also attempted to prevent a post-war atomic arms race with the Soviet Union, which he believed to be a serious threat. In 1944, Bohr presented several key points he believed to be essential concerning international nuclear weapon control. He urged that Britain and the United States should inform the Soviet Union about the Manhattan Project in order to decrease the likelihood of its feeling threatened on the premise that the other nations were building a bomb behind its back. His beliefs stemmed from his conviction that the Russians already knew about the Manhattan Project, leading him to believe there was no point in hiding it from them.

Bohr's evidence came from an interpretation of a letter he received from a Soviet friend and scientist in Russia, which he showed to the British security services. He reasoned that the longer the United States and Britain hid their nuclear advances, the more threatened the Russians would feel and the more inclined to speed up their effort to produce an atomic bomb of their own. With the help of U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

justice Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an Austrian-American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, during which period he was a noted advocate of judic ...

, Bohr met on 26 August 1944 with the President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, who was initially sympathetic to his ideas about controlling nuclear weapons. But Churchill was adamantly opposed to informing the Soviet Union of such work. At the Second Quebec Conference

Princess Alice, and Clementine Churchill">Princess Alice, Countess of Athlone">Princess Alice, and Clementine Churchill during the conference.

The Second Quebec Conference (codenamed "OCTAGON") was a high-level military conference held during ...

in September 1944, Roosevelt sided with Churchill, deciding it would be in the nation's best interest to keep the atomic bomb project a secret. Moreover, they decided Bohr was potentially dangerous and that security measures must be taken in order to prevent him from leaking information to the rest of the world, Russia in particular.

Tube Alloys and the United States

Tizard mission

In August 1940, a British mission, led by Tizard and with members including Cockcroft, was sent to America to create relations and help advance the research towards war technology with the Americans. Several military technologies were shared, including advances in radar, anti-submarine warfare, aeronautical engineering and explosives. The American radar programme in particular was reinvigorated with an added impetus to the development of microwave radar and proximity fuzes. This prompted the Americans to create theMIT Radiation Laboratory

The Radiation Laboratory, commonly called the Rad Lab, was a microwave and radar research laboratory located at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It was first created in October 1940 and operated until 31 ...

, which would later serve as a model for the Los Alamos Laboratory. The mission did not spend much time on nuclear fission, with only two meetings of the subject, mainly about uranium enrichment. In particular, Cockcroft did not report Peierls' and Frisch's findings. Nonetheless, there were important repercussions. A barrier had been broken and a pathway to exchange technical information between the two countries was developed. Moreover, the notion of civilian scientists playing an important role in the development of military technologies was strengthened on both sides of the Atlantic.

Oliphant's visit to the United States

The MAUD Committee reports urged the co-operation with the United States should be continued in the research of nuclear fission. Charles C. Lauritsen, a Caltech physicist working at the

The MAUD Committee reports urged the co-operation with the United States should be continued in the research of nuclear fission. Charles C. Lauritsen, a Caltech physicist working at the National Defense Research Committee

The National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) was an organization created "to coordinate, supervise, and conduct scientific research on the problems underlying the development, production, and use of mechanisms and devices of warfare" in the Un ...

(NDRC), was in London during this time and was invited to sit in on a MAUD meeting. The committee pushed for rapid development of nuclear weapons using gaseous-diffusion as their isotope separation device. Once he returned to the United States, he was able to brief Vannevar Bush

Vannevar Bush ( ; March 11, 1890 – June 28, 1974) was an American engineer, inventor and science administrator, who during World War II headed the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), through which almost all warti ...

, the director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development

The Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) was an agency of the United States federal government created to coordinate scientific research for military purposes during World War II. Arrangements were made for its creation during May 1 ...

(OSRD), concerning the details discussed during the meeting.

In August 1941, Mark Oliphant, the director of the physics department at the University of Birmingham and an original member of the MAUD Committee, was sent to the US to assist the NDRC on radar. During his visit he met with William D. Coolidge. Coolidge was shocked when Oliphant told him the British had predicted that only ten kilograms of uranium-235 would be sufficient to supply a chain reaction effected by fast moving neutrons. While in America, Oliphant discovered that the chairman of the OSRD S-1 Section, Lyman Briggs, had locked away the MAUD reports transferred from Britain entailing the initial discoveries and had not informed the S-1 Committee members of all its findings.

Oliphant took the initiative himself to enlighten the scientific community in the U.S. of the recent groundbreaking discoveries the MAUD Committee had just exposed. Oliphant also travelled to Berkeley to meet with Ernest Lawrence

Ernest Orlando Lawrence (August 8, 1901 – August 27, 1958) was an American nuclear physicist and winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939 for his invention of the cyclotron. He is known for his work on uranium-isotope separation fo ...

, inventor of the cyclotron. After Oliphant informed Lawrence of his report on uranium, Lawrence met with NDRC chairman James Bryant Conant, George B. Pegram, and Arthur Compton to relay the details which Oliphant had directed to Lawrence. Oliphant was not only able to get in touch with Lawrence, he met with Conant and Bush to inform them of the significant data the MAUD had discovered. Oliphant's ability to inform the Americans led to Oliphant convincing Lawrence, Lawrence convincing Compton, and then George Kistiakowsky

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)