Tryggve Gran on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jens Tryggve Herman Gran (20 January 1888 ŌĆō 8 January 1980) was a Norwegian aviator, polar explorer and author.

He was the skiing expert on the 1910ŌĆō13 Scott Antarctic Expedition and was the first person to fly across the North Sea from Scotland to Norway in a heavier-than-air aircraft in August 1914. During WW1 he joined the

Gran took an interest in science and exploration which in 1910 led to

Gran took an interest in science and exploration which in 1910 led to

On his return voyage, Gran met aviator Robert Loraine, the first pilot to cross the Irish Sea, and immediately took an interest in aviation. According to his own words in a newspaper report, Gran learned to fly in early 1913 at Hendon Aerodrome at the Temple School of Aviation, but seems not to have gained his British Aviator's Certificate at the time. His instructor, George Lee Temple (who also taught Max Le Verrier, who flew in

On his return voyage, Gran met aviator Robert Loraine, the first pilot to cross the Irish Sea, and immediately took an interest in aviation. According to his own words in a newspaper report, Gran learned to fly in early 1913 at Hendon Aerodrome at the Temple School of Aviation, but seems not to have gained his British Aviator's Certificate at the time. His instructor, George Lee Temple (who also taught Max Le Verrier, who flew in  He went to France and bought a two-seater Bl├®riot XI-2 "Artillerie", from Bl├®riot A├®ronautique with an 80 hp

He went to France and bought a two-seater Bl├®riot XI-2 "Artillerie", from Bl├®riot A├®ronautique with an 80 hp

In the event he was commissioned on 1 January 1917 as a probationary temporary second lieutenant in the RFC. He was initially assigned to 11 Reserve Training Squadron, part of the

In the event he was commissioned on 1 January 1917 as a probationary temporary second lieutenant in the RFC. He was initially assigned to 11 Reserve Training Squadron, part of the  Gran was confirmed in his rank and appointed a Flying Officer on 1 March 1917. He was posted to B flight of 39 Squadron based at RFC Sutton's Farm in the London Air Defence Area, part of the Home Defence wing. 39 Squadron usually flew

Gran was confirmed in his rank and appointed a Flying Officer on 1 March 1917. He was posted to B flight of 39 Squadron based at RFC Sutton's Farm in the London Air Defence Area, part of the Home Defence wing. 39 Squadron usually flew  On 28 August 1917 Gran was assigned to the newly formed 101 Squadron on the

On 28 August 1917 Gran was assigned to the newly formed 101 Squadron on the

He immediately joined the crew of

He immediately joined the crew of

A friend of Gran's, Captain Larry Carter, had bought an ex-RAF

A friend of Gran's, Captain Larry Carter, had bought an ex-RAF

While flying together, Rickards and Gran were forced down by bad weather and landed at Waddon (later

While flying together, Rickards and Gran were forced down by bad weather and landed at Waddon (later

In 1931 Gran proposed a solo attempt to reach the South Pole on a motorcycle.

Gran received the Cross of the L├®gion d'honneur in 1934. It was awarded on 24 July by General Denain, French Air Minister at the fr:Cercle Militaire, on the occasion of a dinner given by the minister. Gran and other Norwegian flyers were in Paris as part of the festivities to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Bl├®riot's historic cross-channel flight. It was also almost exactly 20 years since Gran's 500 km record-breaking flight to Norway. The party earlier visited Villacoublay, and also laid a floral wreath at the

In 1931 Gran proposed a solo attempt to reach the South Pole on a motorcycle.

Gran received the Cross of the L├®gion d'honneur in 1934. It was awarded on 24 July by General Denain, French Air Minister at the fr:Cercle Militaire, on the occasion of a dinner given by the minister. Gran and other Norwegian flyers were in Paris as part of the festivities to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Bl├®riot's historic cross-channel flight. It was also almost exactly 20 years since Gran's 500 km record-breaking flight to Norway. The party earlier visited Villacoublay, and also laid a floral wreath at the  During the Second World War, Gran was reportedly a member of '' Nasjonal Samling'' (NS), Vidkun Quisling's

During the Second World War, Gran was reportedly a member of '' Nasjonal Samling'' (NS), Vidkun Quisling's

''Under Britisk Flag: Krigen 1914ŌĆō1918''

ŌĆō (1919) * ''Triumviratet'' ŌĆō (1921) * ''En helt: Kaptein Scotts siste f├”rd'' ŌĆō (1924) * ''Mellom himmel og jord'' ŌĆō (1927) * ''Heia ŌĆō La Villa'' ŌĆō (1932) * ''Stormen p├ź Mont Blanc'' ŌĆō (1933) * ''La Villa i kamp'' ŌĆō (1934) * ''Slik var det: Fra kryp til flyger'' ŌĆō (1945) * ''Slik var det: Gjennom livets passat'' ŌĆō (1952) * ''Kampen om Sydpolen'' ŌĆō (1961) * ''F├Ėrste fly over Nordsj├Ėen: Et femti├źrsminne'' ŌĆō (1964) * ''Fra tjuagutt til sydpolfarer'' ŌĆō (1974) * ''Mitt liv mellom himmel og jord'' ŌĆō (1979)

Royal Flying Corps

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colors =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, decorations ...

and flew night bombing raids on the Western Front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

*Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a majo ...

, for which he was awarded the Military Cross. He co-piloted the first flight from London via Oslo to Stockholm in 1920.

During WW2 he aligned himself with Vidkun Quisling's ruling party, and was sentenced to 18 months in prison in 1948.

Early life

Tryggve Gran was born in Bergen, Norway, growing up in an affluent family dominant in the shipbuilding industry. His great-grandfather Jens Gran Berle (1758ŌĆō1828), had founded a shipyard in the Laksev├źg borough of the city of Bergen. His father, Jens Gran (1828 ŌĆō 94) who had inherited the shipbuilding business, died when Tryggve was only five years old. In 1900, after school in Bergen andLillehammer

Lillehammer () is a municipality in Innlandet county, Norway. It is located in the traditional district of Gudbrandsdal. The administrative centre of the municipality is the town of Lillehammer. Some of the more notable villages in the municip ...

, Gran was sent to a school in Lausanne, Switzerland for a year, where he learned some German and French. Three years later, he met the German emperor, Wilhelm II, a common guest with the families of Tryggve's friends. Meeting the emperor made an impact on the then 14-year-old boy, who from that moment on wanted to become a naval officer. At this time, he had several years behind him as a member of the Nygaards Battalion, one of Bergen's buekorps

Buekorps (; literally "Bow Corps" or "Archery Brigade") are traditional marching neighbourhood youth organizations in Bergen, Norway.

The tradition is unique to Bergen. The organizations, which are called ''bataljoner'' (battalions), were first ...

. He entered the Royal Norwegian Naval Academy

The Royal Norwegian Naval Academy (RNoNA, ''Sj├Ėkrigsskolen'' in Norwegian) is located at Laksev├źg in Bergen. It was formally established 27 October 1817 in Frederiksvern. The institution educates officers for the Royal Norwegian Navy.

History

...

in 1907 and graduated in the spring of 1910.

Career

Polar exploration

Gran took an interest in science and exploration which in 1910 led to

Gran took an interest in science and exploration which in 1910 led to Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen (; 10 October 186113 May 1930) was a Norwegian polymath and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. He gained prominence at various points in his life as an explorer, scientist, diplomat, and humanitarian. He led the team t ...

recommending his services to Robert Falcon Scott, who was in Norway at the time preparing for an expedition to the Antarctic

The Antarctic ( or , American English also or ; commonly ) is a polar region around Earth's South Pole, opposite the Arctic region around the North Pole. The Antarctic comprises the continent of Antarctica, the Kerguelen Plateau and other ...

and testing the motor tractor he intended to take with him. Scott was impressed with Gran, who was an expert skier, and Nansen convinced Scott to take Gran as ski instructor to Scott's men for the Terra Nova Expedition.

Arriving in Antarctica in early January 1911, Gran was one of the 13 expedition members involved in the laying of the supply depots needed for the attempt to reach the South Pole later that year. From November 1911 to February 1912, while Scott and the rest of the Southern party were on their journey to the Pole, Gran accompanied the geological expedition to the western mountains led by Griffith Taylor

Thomas Griffith "Grif" Taylor (1 December 1880 ŌĆō 5 November 1963) was an English-born geographer, anthropologist and world explorer. He was a survivor of Captain Robert Scott's Terra Nova Expedition to Antarctica (1910ŌĆō1913). Taylor was a se ...

.

In November 1912, Gran was part of the 11-man search party that found the tent containing the dead bodies of the past South Pole party. After collecting the party's personal belongings the tent was lowered over the bodies of Scott and his two companions and a 12-foot snow cairn was built over it. A pair of skis were used to form a cross over their grave. Gran travelled back to the base at Cape Evans wearing Scott's skis, reasoning that at least Scott's skis would complete the journey. Before leaving Antarctica he made an ascent of Mount Erebus with Raymond Priestley and Frederick Hooper in December 1912, an occasion which nearly ended in disaster when an unexpected eruption caused a shower of huge pumice blocks to fall around him. On 24 July 1913 Gran was awarded the Polar Medal by King George V.

Aviation: crossing the North Sea

Escadrille 112

''Escadrille Spa.112'' (also known as ''Escadrille V.29'', ''Escadrille VB.112'', ''Escadrille F.112'', and ''Escadrille N.112'') was a French air force squadron active for the near-entirety of World War I. After serving until mid-1917 in various ...

during the war) died in a flying accident in 1914 aged only 21.

He went to France and bought a two-seater Bl├®riot XI-2 "Artillerie", from Bl├®riot A├®ronautique with an 80 hp

He went to France and bought a two-seater Bl├®riot XI-2 "Artillerie", from Bl├®riot A├®ronautique with an 80 hp Gnome

A gnome is a mythological creature and diminutive spirit in Renaissance magic and alchemy, first introduced by Paracelsus in the 16th century and later adopted by more recent authors including those of modern fantasy literature. Its characte ...

engine for 20,000 francs. At the Bl├®riot school at Buc he was one of the first to loop the loop

The generic roller coaster vertical loop, where a section of track causes the riders to complete a 360 degree turn, is the most basic of roller coaster inversions. At the top of the loop, riders are completely inverted.

History

The vertical ...

and fly upside down.

On 30 July 1914 Gran became the first pilot to cross the North Sea. Taking off in his Bl├®riot XI-2 monoplane, named ''Ca Flotte'' (it was equipped with air cushions in case of ditching)) from Cruden Bay, Scotland, Gran landed 4 hours 10 minutes later at J├”ren, near Stavanger

Stavanger (, , American English, US usually , ) is a city and municipalities of Norway, municipality in Norway. It is the fourth largest city and third largest metropolitan area in Norway (through conurbation with neighboring Sandnes) and the a ...

, Norway, after a flight of . The restored, but complete and original plane is on display at the Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology

The Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology ( no, Norsk Teknisk Museum) is located in Oslo, Norway. The museum is an anchor point on the European Route of Industrial Heritage.

History

The museum as an institution was founded in 1914 as a ...

in Oslo, Norway. This record-breaking achievement, the longest flight over water to date, was overshadowed by the outbreak of World War I only five days later.

First World War

Gran joined the newly formed Norwegian Army Air Service as a Lieutenant on 3 August 1914, and his Bleriot XI was bought by the government. In spring 1915 he was flying aggressive patrols againstGerman U-boat

U-boats were Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the World War I, First and Second World War, Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were ...

s in his Bl├®riot (renamed ''Nords├Ėen'') from a small beach in Western Norway.

:"Suddenly the hum of a Gnome is heard, and like a great bird a Bl├®riot two-seater comes into view, sailing closely over the top of the mountains. It swoops down until its wheels nearly touch the sea, and as it whirrs past, Lieut. Gran and his observer are seen to make signs which can only be interpreted as a polite but firm request to 'get out.'"

Gran had flown more than over the sea from the start of the war, on one occasion covering a distance of nearly . On 9 September 1915, Gran made a flight in his Bl├®riot from Elvenes in Salangen

Salangen is a municipality in Troms og Finnmark county, Norway. The administrative centre of the municipality is the village of Sj├Ėvegan, where most of the people in the municipality live. Other villages include Elvenes, Laberg, and Seljesko ...

municipality in northern Norway, within the Arctic circle

The Arctic Circle is one of the two polar circles, and the most northerly of the five major circles of latitude as shown on maps of Earth. Its southern equivalent is the Antarctic Circle.

The Arctic Circle marks the southernmost latitude at w ...

. Later that year he was sent to Britain and France to study air defence.

By March 1916, nothing had been heard of Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition since December 1914, and he offered to go on a relief ship to search for the Ross Sea party

The Ross Sea party was a component of Sir Ernest Shackleton's 1914ŌĆō1917 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. Its task was to lay a series of supply depots across the Great Ice Barrier from the Ross Sea to the Beardmore Glacier, along the polar ...

and the '' Aurora''. However, the ''Aurora '' arrived in New Zealand in April, and Shackleton managed to reach South Georgia

South Georgia ( es, Isla San Pedro) is an island in the South Atlantic Ocean that is part of the British Overseas Territory of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. It lies around east of the Falkland Islands. Stretching in the eastŌĆ ...

in May, and the relief ship was not needed. A newspaper report of the same date claimed that he was now a lieutenant in the Royal Norwegian Navy Air Service.

On 18 October 1916 he was back in Norway, and persuaded the Norwegian Minister of War Christian Holtfodt to be allowed to volunteer for the Royal Flying Corps

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colors =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, decorations ...

(RFC), and obtain lessons in night flying. Returning to London, he was interviewed at the Norwegian Legation and then by Lt-Col. Felton Holt

Air Vice Marshal Felton Vesey Holt, (23 February 1886 ŌĆō 23 April 1931) was a squadron and wing commander in the Royal Flying Corps who became a brigadier general in the newly established Royal Air Force (RAF) just before the end of the First ...

, Officer Commanding, 16th/Home Defence Wing RFC. It was agreed that to circumvent the problem of his neutral Norwegian nationality, he would be given a commission under the assumed identity of "Teddy Grant", a Canadian aviator.

London Air Defence Area

The London Air Defence Area (LADA) was the name given to the organisation created to defend London from the increasing threat from German airships during World War I. Formed in September 1915, it was commanded initially by Admiral Sir Percy Scott ...

, based at RAF Northolt. At 11 Reserve Training Squadron he received more flying lessons from Lieutenant B. F. Moore, an old acquaintance from Gran's flying days at Hendon in 1913. He "personally took my instruction in hand, and after some flights with him at the helm, I finally took the driver's seat myself."

Gran was swiftly made an instructor. By chance, Billy Bishop

Air Marshal William Avery Bishop, (8 February 1894 ŌĆō 11 September 1956) was a Canadian flying ace

A flying ace, fighter ace or air ace is a military aviator credited with shooting down five or more enemy aircraft during aerial com ...

had been posted to the same Training Squadron a month earlier in December 1916, for further lessons before joining his official unit, 37 Squadron. Bishop had previously been an observer and had learned to fly at RAF Upavon from September 1916. Bishop's extreme antipathy towards discipline led him into severe conflict with his Commanding Officer (CO). Gran's arrival may well saved Bishop's career as a pilot. They apparently got on well, and as a result of Gran's intercedings with his CO, Bishop only received a severe reprimand and was posted to 37 Squadron (Home Defence) and then in March 1917 to 60 Squadron in France, where he won the VC.

What seems to be a barely-concealed official excuse for Gran's permission to join the RFC appeared in a Norwegian newspaper: "It's a curious story that comes from the ''Christiania Dagblad'' regarding Lieut. Tryggve Gran, who will be remembered by his aeroplane flight over the North Sea some little time ago. Lieut. Gran has been, it is stated, ordered to resign his commission in the Norwegian Flying Corps for having appeared in uniform in a foreign country, it being added that he will probably become a naturalised British subject and join the British Flying Corps."

Gran was confirmed in his rank and appointed a Flying Officer on 1 March 1917. He was posted to B flight of 39 Squadron based at RFC Sutton's Farm in the London Air Defence Area, part of the Home Defence wing. 39 Squadron usually flew

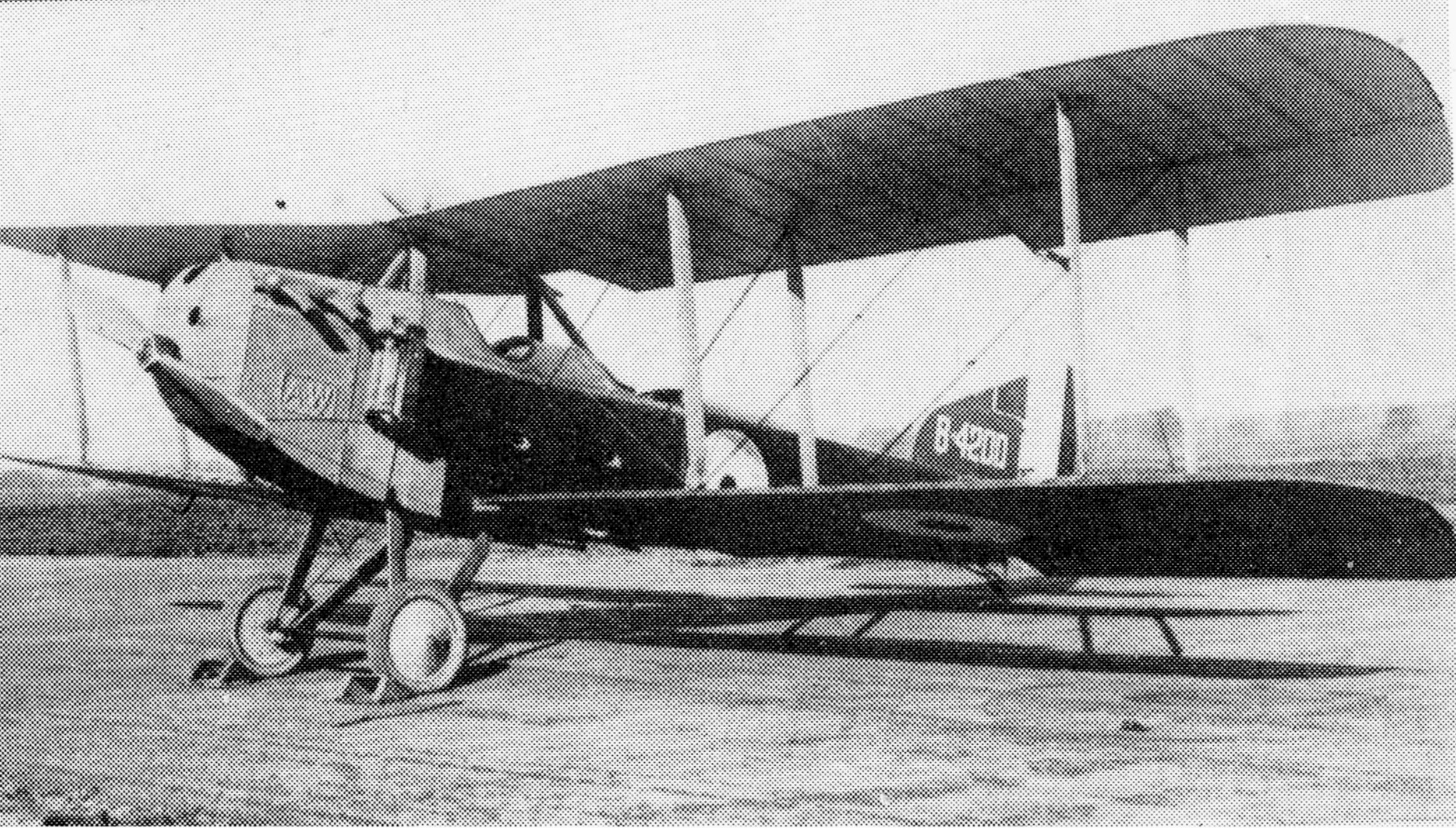

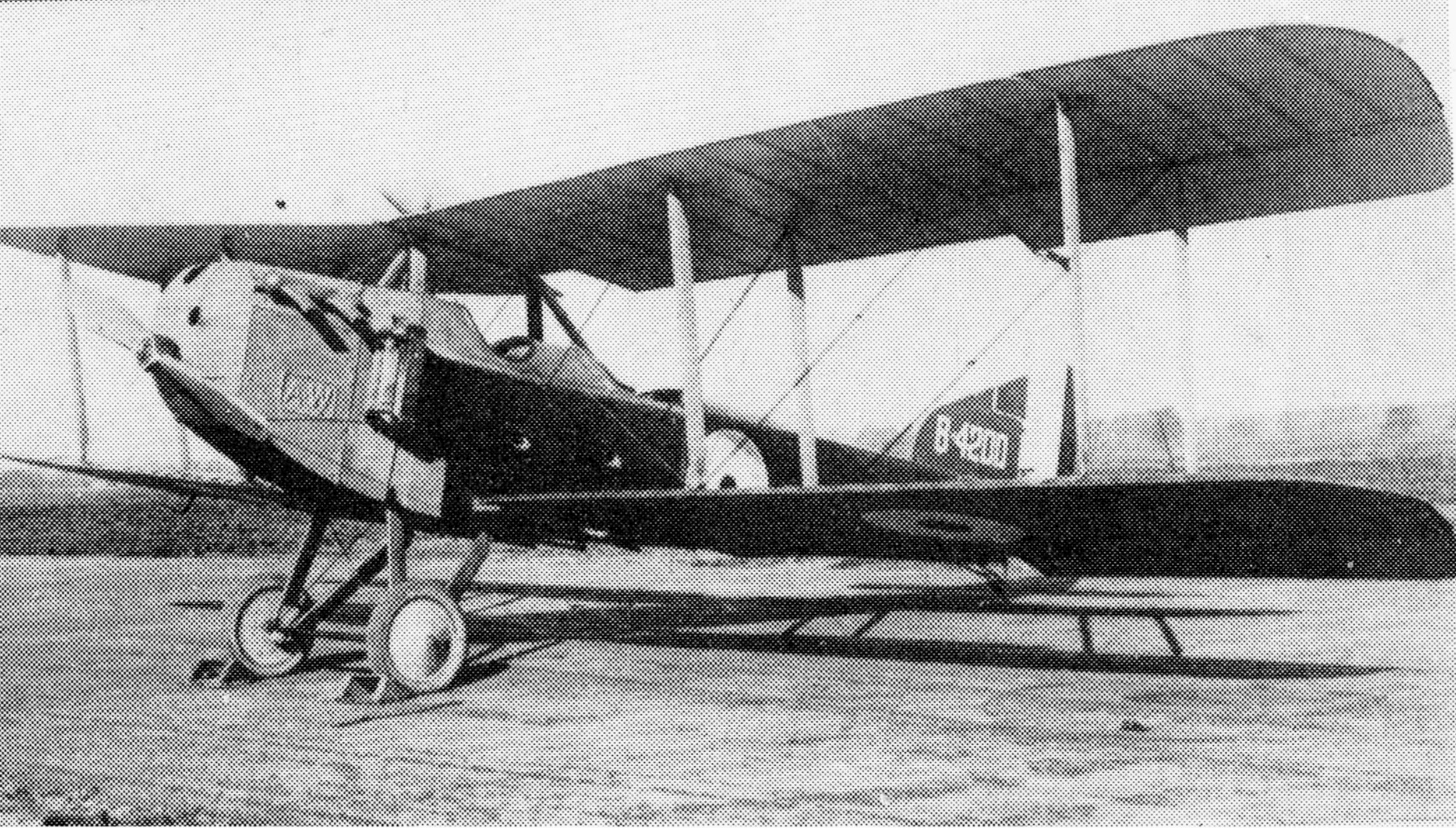

Gran was confirmed in his rank and appointed a Flying Officer on 1 March 1917. He was posted to B flight of 39 Squadron based at RFC Sutton's Farm in the London Air Defence Area, part of the Home Defence wing. 39 Squadron usually flew Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2

The Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2 was a British single-engine tractor two-seat biplane designed and developed at the Royal Aircraft Factory. Most of the roughly 3,500 built were constructed under contract by private companies, including establish ...

s and B.E.12

The Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.12 was a British single-seat aeroplane of The First World War designed at the Royal Aircraft Factory. It was essentially a single-seat version of the B.E.2.

Intended for use as a long-range reconnaissance and bomb ...

s, but the unit operated at least one Armstrong Whitworth F.K.8., the type which Gran would later fly to make the first (indirect) flight from London to Stockholm via Kristiania.

The squadron flew against Zeppelin and Sch├╝tte-Lanz airships, which resumed their attacks in mid-March 1917, and also Gothas such as the Gotha G.V, and 'Giant' Riesenflugzeug bombers. On 13 June Gran was airborne in a B.E.12, from RFC North Weald (another 39 Sqn airfield) when he narrowly failed to shoot down a Gotha.

On 24 July 1917 he was posted to the recently formed 44 Squadron, also part of Home Defence, based at Hainault Farm, Ilford, Essex (later RAF Fairlop

Royal Air Force Fairlop or more simply RAF Fairlop is a former Royal Air Force satellite station situated near Ilford in Essex. Fairlop is now a district in the London Borough of Redbridge, England.

History

First World War

A site to the ea ...

), flying Sopwith Camels. His Commanding Officer was Major (later Wing Commander) T. OŌĆÖB. Hubbard. It's not entirely clear how Gran managed to progress as far as he did without a valid pilot's license

Pilot licensing or certification refers to permits for operating aircraft. Flight crew licences are regulated by ICAO Annex 1 and issued by the civil aviation authority of each country. CAAŌĆÖs have to establish that the holder has met a specifi ...

, but on 2 August 1917 he finally received Royal Aero Club Aviators' Certificate No. 5000.

On 28 August 1917 Gran was assigned to the newly formed 101 Squadron on the

On 28 August 1917 Gran was assigned to the newly formed 101 Squadron on the Western Front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

*Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a majo ...

in France. He was briefly sent to 70 Squadron - apparently a staging post before joining his official unit - arriving there on 1 September 1917. A few days later he was with 101 Squadron, flying Royal Aircraft Factory F.E.2

Between 1911 and 1914, the Royal Aircraft Factory used the F.E.2 (Farman Experimental 2) designation for three quite different aircraft that shared only a common "Farman" pusher biplane layout.

The third "F.E.2" type was operated as a day and n ...

b/d night fighters. The squadron was stationed at Clairmarais aerodrome (a satellite airfield for RFC Saint-Omer) from 31 August 1917 to 2 February 1918. The CO was Major the Hon. Laurence Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes, the second son of 18th Baron Saye and Sele.

101 Squadron flew night bombing missions with F.E.2bs during Battle of Menin Road

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

, 3rd Battle of Ypres

The Third Battle of Ypres (german: link=no, Dritte Flandernschlacht; french: link=no, Troisi├©me Bataille des Flandres; nl, Derde Slag om Ieper), also known as the Battle of Passchendaele (), was a campaign of the First World War, fought by t ...

and the Battle of Cambrai. Gran carried out 17 night bombing raids. He was awarded the Military Cross (gazetted 26 March 1918) for his exploits. On 30 November 1917, 101 squadron's targets were Cambrai

Cambrai (, ; pcd, Kimbr├®; nl, Kamerijk), formerly Cambray and historically in English Camerick or Camericke, is a city in the Nord (French department), Nord Departments of France, department and in the Hauts-de-France Regions of France, regio ...

, Dechy

Dechy () is a commune in the Nord department in northern France.

Population

Heraldry

See also

*Communes of the Nord department

The following is a list of the 648 communes of the Nord department of the French Republic.

The communes coo ...

, and Marquion

Marquion () is a commune in the Pas-de-Calais department in the Hauts-de-France region of France.

Geography

Marquion is a farming and light industrial village situated southwest of Arras, at the junction of the D939 and the D15 roads. Junction 8 ...

. That night he was badly wounded in the leg by anti-aircraft fire

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based, ...

('Archie') while flying over occupied territory, managed to land just inside Allied lines and hospitalised. He returned to England from 16 December 1917 and recovered in the Royal Free Hospital

The Royal Free Hospital (also known simply as the Royal Free) is a major teaching hospital in the Hampstead area of the London Borough of Camden. The hospital is part of the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust, which also runs services at Barn ...

.

In his book recounting his wartime experiences, Gran reproduces three letters dated August to October 1917 from James McCudden

James Thomas Byford McCudden, (28 March 1895 ŌĆō 9 July 1918) was a British flying ace of the First World War and among the most highly decorated airmen in British military history.

Born in 1895 to a middle class family with military traditions ...

"in his own handwriting", but omits to mention that he wasn't the original recipient. The letters were apparently sent to Gran's friend 2nd Lt. Lester (Larry) Carter, who later flew with Gran to Norway in June 1920 in an Armstrong Whitworth F.K.8

The Armstrong Whitworth F.K.8 was a British two-seat general-purpose biplane built by Armstrong Whitworth during the First World War. The type served alongside the better known R.E.8 until the end of the war, at which point 694 F.K.8s remained ...

.

He was appointed a Flight Commander on 1 January 1918 with the rank of acting captain, by which time he was able to walk with crutches. and in March his seniority as second lieutenant was backdated to 1 January 1917. On 20 March 1918 he got permission to go to Norway for a few weeks to recover from his foot/leg injury, and a few days later he was awarded the Military Cross. His citation reads:

:T./Capt. Tryggve Gran, Gen. List and R.F.C.

:For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. He bombed enemy aerodromes with great success, and engaged enemy searchlights, transport and other targets with machine-gun fire. He invariably showed the greatest determination and resource.

He was married to his first wife on April 29, 1918, reportedly wearing the Mons Star, although it seems unlikely that he was entitled to it.

He was promoted acting major (squadron commander) on 10 September 1918, and received an offer to go to northern Russia to lead a flying detachment of the Royal Air Force during the Allied intervention in the North Russia Campaign

The North Russia intervention, also known as the Northern Russian expedition, the Archangel campaign, and the Murman deployment, was part of the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War after the October Revolution. The intervention brought ...

. On 20 September 1918 he departed from Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, D├╣n D├© or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

, arriving in Archangelsk

Arkhangelsk (, ; rus, ąÉčĆčģą░╠üąĮą│ąĄą╗čīčüą║, p=╔Ér╦łxan╔Ī╩▓╔¬l╩▓sk), also known in English as Archangel and Archangelsk, is a city and the administrative center of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. It lies on both banks of the Northern Dvina near i ...

ten days later, although he doesn't appear to have achieved much. In his memoirs he doesn't mention meeting Sir Ernest Shackleton, who was also there from October 1918. In October his leg wound was troubling him in the extreme cold, and the RFC doctor advised him to get a transfer. He returned to Norway on 8 November, a few days before the Armistice. Gran was temporarily transferred to the RAF unemployed list on 26 April 1919.

Attempt at first trans-Atlantic flight

He immediately joined the crew of

He immediately joined the crew of Handley Page

Handley Page Limited was a British aerospace manufacturer. Founded by Frederick Handley Page (later Sir Frederick) in 1909, it was the United Kingdom's first publicly traded aircraft manufacturing company. It went into voluntary liquidation a ...

's entry, a V/1500 four-engined bomber, in the Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper and news websitePeter Wilb"Paul Dacre of the Daily Mail: The man who hates liberal Britain", ''New Statesman'', 19 December 2013 (online version: 2 January 2014) publish ...

's Transatlantic Air Race, which had been postponed during the war. The pilot was Major Herbert G. Brackley

Herbert G Brackley was a pioneer of civil aviation during the first half of the twentieth century.

Early life

Brackley was born on 4 October 1894. During his early life, Brackley moved around many times, living for part of his life at 20 Umfrev ...

, and the co-pilot was recently retired Admiral Mark Kerr, the first Naval Flag Officer to become a pilot. Gran was the navigator and relief pilot. During testing in Harbour Grace, Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

in May 1919, the engines boiled over because of faulty radiators. While the team was waiting for the latest radiators to arrive from England Alcock and Brown (who had arrived on 24 May 1919), had assembled their Vickers Vimy, tested it, and taken off on 14 June to win the competition.

A publicity stunt organised by Handley Page to fly the V/1500 straight to New York in early July 1919 was cut short when the aircraft suffered overheating engines again and crashed at Parrsboro racecourse, Nova Scotia. The navigator's seat from the V/1500 is in the Ottawa House Museum, Parrsboro. The repairs were going to take three months, and on 1 August Gran was granted a permanent commission in the RAF with the rank of captain. He returned to the UK; the V/1500 eventually made it to New York in October 1919.

Flights to Scandinavia

In 1918 Handley Page (HP) and :no:Wilhelm Meisterlin (HP's general agent in Norway) had already planned to form an Anglo-Norwegian airline company, flying from Kristiania toGothenburg

Gothenburg (; abbreviated Gbg; sv, G├Čteborg ) is the second-largest city in Sweden, fifth-largest in the Nordic countries, and capital of the V├żstra G├Čtaland County. It is situated by the Kattegat, on the west coast of Sweden, and has ...

and Copenhagen. HP was also going to run scheduled flights from Copenhagen to London. In order to test this route, Gran and Captain J. Stewart flew a Handley Page O/400

The Handley Page Type O was a biplane bomber used by Britain during the First World War. When built, the Type O was the largest aircraft that had been built in the UK and one of the largest in the world. There were two main variants, the Handl ...

(G-EAKE) on 16 August 1919 from London via Soesterberg to the Danish Army airport Kl├Ėvermarken near Copenhagen; then on to ├ģrhus, and Kjeller Airport

Kjeller Airport ( no, Kjeller flyplass; ) is a military and general aviation airport located in Kjeller in Skedsmo in Viken county, Norway. Situated in the outskirts of Lillestr├Ėm, it is east northeast of Oslo, making it the airport located th ...

near Kristiania. The first flight from Kristiania to Stockholm was planned, and on 6 September the O/400 with Stewart, Gran and his English wife as a passenger took off from Kjeller. But the Handley-Page crashed shortly after takeoff with a seized engine; no-one was injured and the aircraft was badly damaged although repairable. Gran returned to the UK and his commission was cancelled again on 2 December 1919.

A friend of Gran's, Captain Larry Carter, had bought an ex-RAF

A friend of Gran's, Captain Larry Carter, had bought an ex-RAF Armstrong Whitworth F.K.8

The Armstrong Whitworth F.K.8 was a British two-seat general-purpose biplane built by Armstrong Whitworth during the First World War. The type served alongside the better known R.E.8 until the end of the war, at which point 694 F.K.8s remained ...

with the idea of flying it non-stop to Sweden. The F.K.8 was registered as a civil aircraft to Gran on 9 June 1920: they set off from Dover on 17 June, and arrived at ├ģrhus after several delays on 23 June. News came from Norway that the O/400 had been repaired in Kjeller after the winter, and they changed the plan to be the first to fly from Kristiania to Stockholm. Crossing the Skaggerak they arrived in Kjeller in the early hours of 25 June. The final leg of the journey continued in the permanent twilight of the night of the 24/25 June 1920, when Carter and Gran flew from Kjeller to Stockholm in slightly over 2.5 hours: they thus became the first to fly (somewhat indirectly) from London to Stockholm. The Handley Page O/400 arrived from Norway the next evening. A return race was planned, and on June 30 Gran and Carter took off. However, the engine caught fire over ├¢rebro, and after a forced landing they extinguished the fire. On taking off again, however, the F.K.8 nosed over and was wrecked although the pair of flyers received only relatively minor injuries.

RAF flying instructor

Gran received another commission as a Flight Lieutenant on 22 September 1920. He joined the staff of the Air Pilotage School (variously No. 2 Navigation School, later School of Aerial Navigation) at RAF Andover that month. Another instructor at Andover was Flying Officer (later Wing Commander) Aubrey R. M. Rickards. While flying together, Rickards and Gran were forced down by bad weather and landed at Waddon (later

While flying together, Rickards and Gran were forced down by bad weather and landed at Waddon (later Croydon Airport

Croydon Airport (former ICAO code: EGCR) was the UK's only international airport during the interwar period. Located in Croydon, South London, England, it opened in 1920, built in a Neoclassical style, and was developed as Britain's main air ...

) where the Aircraft Disposals Company was being managed by Handley Page. They had a look round at the war surplus aircraft, and they both subsequently bought a Sopwith Pup. Pup G-EAVW (works No. C312) was registered to Gran on 27 October 1920, while Rickards bought G-EAVX. It appears that they tried to fly their Pups together to Norway via Holland in December 1920, but the prevailing wind forced them to Newcastle, where they caught a steamship to Norway.

In the spring of 1921 Gran was in collision with a motorcycle in London and injured his left leg so severely that he was unable to resume active flying, and he returned home to Norway. Gran finally relinquished his commission on 6 August 1921.

In May 1922 Gran travelled with the future Olympic skiers Thorleif Haug and Jacob Tullin Thams to Svalbard

Svalbard ( , ), also known as Spitsbergen, or Spitzbergen, is a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. North of mainland Europe, it is about midway between the northern coast of Norway and the North Pole. The islands of the group range ...

to prepare for a ski trip across the ice sheet. From Ny-├ģlesund

Ny-├ģlesund ("New ├ģlesund") is a small town in Oscar II Land on the island of Spitsbergen in Svalbard, Norway. It is situated on the Br├Ėgger peninsula ( Br├Ėggerhalv├Ėya) and on the shore of the bay of Kongsfjorden. The company town is owned and ...

they were to go skiing and sledding for a month to "study the country, the equipment and ourselves"; at the same time they were to shoot a film about Svalbard. This time Gran did not manage to raise enough money for two planes and equipment, and the trip was abandoned.

Later civilian career

After the war, Gran started holding lectures on aviation and his journeys to the polar areas, as well as writing books. In 1928, he sailed on the ''Veslekari'' as part of a concerted effort to search for the polar explorer Roald Amundsen, lost flying while trying to discover the fate of Umberto Nobile's North Pole expedition on board the ''Airship Italia

The ''Italia'' was a semi-rigid airship belonging to the Italian Air Force. It was designed by Italian engineer and General Umberto Nobile who flew the dirigible in his second series of flights around the North Pole. The ''Italia'' crashed in ...

''.

In 1931 Gran proposed a solo attempt to reach the South Pole on a motorcycle.

Gran received the Cross of the L├®gion d'honneur in 1934. It was awarded on 24 July by General Denain, French Air Minister at the fr:Cercle Militaire, on the occasion of a dinner given by the minister. Gran and other Norwegian flyers were in Paris as part of the festivities to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Bl├®riot's historic cross-channel flight. It was also almost exactly 20 years since Gran's 500 km record-breaking flight to Norway. The party earlier visited Villacoublay, and also laid a floral wreath at the

In 1931 Gran proposed a solo attempt to reach the South Pole on a motorcycle.

Gran received the Cross of the L├®gion d'honneur in 1934. It was awarded on 24 July by General Denain, French Air Minister at the fr:Cercle Militaire, on the occasion of a dinner given by the minister. Gran and other Norwegian flyers were in Paris as part of the festivities to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Bl├®riot's historic cross-channel flight. It was also almost exactly 20 years since Gran's 500 km record-breaking flight to Norway. The party earlier visited Villacoublay, and also laid a floral wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

A Tomb of the Unknown Soldier or Tomb of the Unknown Warrior is a monument dedicated to the services of an unknown soldier and to the common memories of all soldiers killed in war. Such tombs can be found in many nations and are usually high-prof ...

.

During the Second World War, Gran was reportedly a member of '' Nasjonal Samling'' (NS), Vidkun Quisling's

During the Second World War, Gran was reportedly a member of '' Nasjonal Samling'' (NS), Vidkun Quisling's collaborationist

Wartime collaboration is cooperation with the enemy against one's country of citizenship in wartime, and in the words of historian Gerhard Hirschfeld, "is as old as war and the occupation of foreign territory".

The term ''collaborator'' dates to t ...

party. The NS used Gran's hero-like status in their war propaganda, and in 1944, a commemorative stamp was issued to mark the 30th anniversary of Gran's flight across the North Sea.

He stood trial in 1948 for his war-time activities. One of the witnesses was ''Oberst'' Gudbrand ├śstbye

Gudbrand ├śstbye (2 October 1885 – 2 June 1972) was a Norwegian army officer and historian. He was born in Gj├Ėvik, a son of factory owner Anders ├śstbye and Ellen Anna Hovdenak. He was married to Ragna Heyerdahl H├Ėrbye, and thus son-in-law ...

, brigade commander for the Norwegian forces in Valdres in 1940. He said that Gran had spent some time in a military jail (''Kakebu'') suspected of being a spy; but on his release he had acted almost like the head of the prison camps and had ordered 300 soldiers to clear snow for farmers in Hemsedal. Gran was found guilty of treason and sentenced to a prison term of 18 months: but since he had already been incarcerated during his arrest he didn't serve any further time in jail.

It has been speculated Gran feared reprisals from the pro-German fascist party because of his commitment to the Royal Air Force in the First World War. Others have speculated that his friendship with G├Čring and bitterness over not being offered a full-time job in the Norwegian Army Air Service may have been reasons for Gran to support the NS during the Nazi occupation of Norway.

The remainder of his life was devoted principally to writing books.

Personal life

Gran was married three times. Firstly, as "Teddy Grant, formerly Tryggve Gran" on 29 April 1918, in London, to actress Lily St. John (Lilian Clara Johnson) who later starred in '' The Naughty Princess'', marriage dissolved 1921; secondly in 1923 to Ingeborg Meinich (1902ŌĆō1997) with whom he had two daughters, the marriage dissolved; lastly in 1941 to Margaret Sch├Ėnheyder, a renowned portrait painter. With his last wife, he had a son, Hermann who was born in 1944. Gran was also a giftedfootball

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kicking a ball to score a goal. Unqualified, the word ''football'' normally means the form of football that is the most popular where the word is used. Sports commonly c ...

player, earning one cap for Norway in 1908. This was Norway's first ever international match, and was played against Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

in Gothenburg

Gothenburg (; abbreviated Gbg; sv, G├Čteborg ) is the second-largest city in Sweden, fifth-largest in the Nordic countries, and capital of the V├żstra G├Čtaland County. It is situated by the Kattegat, on the west coast of Sweden, and has ...

. Gran played as a striker

Striker or The Strikers may refer to:

People

*A participant in a strike action

*A participant in a hunger strike

*Blacksmith's striker, a type of blacksmith's assistant

*Striker's Independent Society, the oldest mystic krewe in America

People wi ...

. Sweden beat Norway 11ŌĆō3.

Tryggve Gran died in his home in Grimstad, Norway on 8 January 1980 aged 91. A memorial was unveiled in Cruden Bay during 1971.

Legacy

Mount Gran

Mount Gran () is a large flat-topped mountain, high, standing at the north side of Mackay Glacier and immediately west of Gran Glacier in Victoria Land, Antarctica. It was discovered by the British Antarctic Expedition, 1910ŌĆō13, which named it ...

and Gran Glacier Gran Glacier () is a glacier in Antarctica that flows south into Mackay Glacier between Mount Gran and Mount Woolnough. It rises from a snow divide with Benson Glacier to the northeast. It was named after Mount Gran by the New Zealand Northern Sur ...

in Antarctica are named after him.

Honours

* Silver Polar Medal (for his part in Robert F. Scott's Antarctic expedition 1910ŌĆō1911) *Order of St. Olav

The Royal Norwegian Order of Saint Olav ( no, Den Kongelige Norske Sankt Olavs Orden; or ''Sanct Olafs Orden'', the old Norwegian name) is a Norwegian order of chivalry instituted by King Oscar I on 21 August 1847. It is named after King Olav II ...

(Norway, 1915, First World War: returned in 1925)

* Military Cross (United Kingdom, 1918, First World War)

* L├®gion d'honneur (France, 1934)

* Order of the Crown of Italy

The Order of the Crown of Italy ( it, Ordine della Corona d'Italia, italic=no or OCI) was founded as a national order in 1868 by King Vittorio Emanuele II, to commemorate the unification of Italy in 1861. It was awarded in five degrees for civi ...

The Canterbury Museum, Christchurch, New Zealand, acquired Gran's four extant medals at a London auction in 2017 for ┬Ż105,000. "The purchase included two of Mr GranŌĆÖs journals as well as his Polar Medal as a member of the Antarctic expedition, United Kingdom Military Cross, French Legion of Honour and Italian Order of the Crown."Pic of two medals & diary:

Publications

* ''Hvor sydlyset flammer'' ŌĆō (1915)''Under Britisk Flag: Krigen 1914ŌĆō1918''

ŌĆō (1919) * ''Triumviratet'' ŌĆō (1921) * ''En helt: Kaptein Scotts siste f├”rd'' ŌĆō (1924) * ''Mellom himmel og jord'' ŌĆō (1927) * ''Heia ŌĆō La Villa'' ŌĆō (1932) * ''Stormen p├ź Mont Blanc'' ŌĆō (1933) * ''La Villa i kamp'' ŌĆō (1934) * ''Slik var det: Fra kryp til flyger'' ŌĆō (1945) * ''Slik var det: Gjennom livets passat'' ŌĆō (1952) * ''Kampen om Sydpolen'' ŌĆō (1961) * ''F├Ėrste fly over Nordsj├Ėen: Et femti├źrsminne'' ŌĆō (1964) * ''Fra tjuagutt til sydpolfarer'' ŌĆō (1974) * ''Mitt liv mellom himmel og jord'' ŌĆō (1979)

See also

*Aviation in Norway

Aviation has been a part of Norwegian society since the early twentieth century.

Early attempts

In the early days of Norwegian aviation the Norwegian enthusiasts lacked an engine and were therefore unable to perform real flights. The first engine ...

References

;Notes ;CitationsBibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Gran, Tryggve 1888 births 1980 deaths People from Bergen Explorers of Antarctica Terra Nova expedition Aviation pioneers Norwegian aviators Norwegian Army Air Service personnel Royal Flying Corps officers Royal Air Force officers Norwegian expatriates in France Norwegian expatriates in the United Kingdom Norway international footballers Norwegian non-fiction writers Norwegian people of World War I Norwegian people of World War II Members of Nasjonal Samling People convicted of treason for Nazi Germany against Norway Recipients of the Military Cross Recipients of the Legion of Honour Recipients of the Polar Medal