Treaty of Zaragoza (1529) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Treaty of Zaragoza, also called the Capitulation of Zaragoza (alternatively spelled Saragossa) was a

In 1494 Castile and Portugal signed the Treaty of Tordesillas, dividing the world into two areas of exploration and colonisation: the Castilian and the Portuguese. It established a

In 1494 Castile and Portugal signed the Treaty of Tordesillas, dividing the world into two areas of exploration and colonisation: the Castilian and the Portuguese. It established a

Transcription of the Spanish-language version of the Treaty

by Cristóbal Bernal * Yasuo Miyakawa

"The changing iconography of Japanese political geography,"

''GeoJournal,'' Vol. 52, No. 4, Iconographies (2000), pp. 345–352. {{Authority control History of the Philippines (1565–1898) Meridians (geography) Geopolitical rivalry

peace treaty

A peace treaty is an agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually countries or governments, which formally ends a state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring ...

between Castile and Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

, signed on 22 April 1529 by King John III of Portugal and the Castilian emperor Charles V Charles V may refer to:

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

* Charles V, Duke of Lorraine (1643–1690)

* Infa ...

, in the Aragonese city of Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. It lies by the Ebro river and its tributari ...

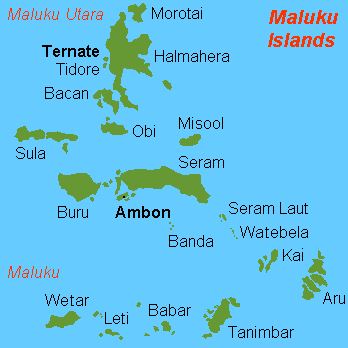

. The treaty defined the areas of Castilian and Portuguese influence in Asia, in order to resolve the "Moluccas issue", which had arisen because both kingdoms claimed the Maluku Islands

The Maluku Islands (; Indonesian: ''Kepulauan Maluku'') or the Moluccas () are an archipelago in the east of Indonesia. Tectonically they are located on the Halmahera Plate within the Molucca Sea Collision Zone. Geographically they are located ...

for themselves, asserting that they were within their area of influence as specified in 1494 by the Treaty of Tordesillas. The conflict began in 1520, when expeditions of both kingdoms reached the Pacific Ocean, because no agreed meridian of longitude had been established in the Orient.

Background: the Moluccas issue

In 1494 Castile and Portugal signed the Treaty of Tordesillas, dividing the world into two areas of exploration and colonisation: the Castilian and the Portuguese. It established a

In 1494 Castile and Portugal signed the Treaty of Tordesillas, dividing the world into two areas of exploration and colonisation: the Castilian and the Portuguese. It established a meridian

Meridian or a meridian line (from Latin ''meridies'' via Old French ''meridiane'', meaning “midday”) may refer to

Science

* Meridian (astronomy), imaginary circle in a plane perpendicular to the planes of the celestial equator and horizon

* ...

in the Atlantic Ocean, with areas west of the line exclusive to Spain, and east of the line to Portugal.

In 1511, Malacca, then the centre of Asian trade, was conquered for Portugal by Afonso de Albuquerque

Afonso de Albuquerque, 1st Duke of Goa (; – 16 December 1515) was a Portuguese general, admiral, and statesman. He served as viceroy of Portuguese India from 1509 to 1515, during which he expanded Portuguese influence across the Indian Ocean ...

. Getting to know the secret location of the so-called "spice islands

A spice is a seed, fruit, root, bark, or other plant substance primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices are distinguished from herbs, which are the leaves, flowers, or stems of plants used for flavoring or as a garnish. Spices are ...

" – the Banda Islands

The Banda Islands ( id, Kepulauan Banda) are a volcanic group of ten small volcanic islands in the Banda Sea, about south of Seram Island and about east of Java, and constitute an administrative district (''kecamatan'') within the Central ...

, Ternate

Ternate is a city in the Indonesian province of North Maluku and an island in the Maluku Islands. It was the ''de facto'' provincial capital of North Maluku before Sofifi on the nearby coast of Halmahera became the capital in 2010. It is off the ...

and Tidore

Tidore ( id, Kota Tidore Kepulauan, lit. "City of Tidore Islands") is a city, island, and archipelago in the Maluku Islands of eastern Indonesia, west of the larger island of Halmahera. Part of North Maluku Province, the city includes the island ...

in Maluku Islands (modern Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

), then the single world source of nutmeg

Nutmeg is the seed or ground spice of several species of the genus ''Myristica''. ''Myristica fragrans'' (fragrant nutmeg or true nutmeg) is a dark-leaved evergreen tree cultivated for two spices derived from its fruit: nutmeg, from its seed, an ...

and cloves, and the main purpose for the European explorations in the Indian Ocean – Albuquerque sent an expedition led by António de Abreu

António de Abreu () was a 16th-century Portuguese navigator and naval officer. He participated under the command of Afonso de Albuquerque in the Capture of Ormuz (1507), conquest of Ormus in 1507 and Capture of Malacca (1511), Malacca in 1511, wh ...

in search of the Moluccas, particularly the Banda Islands. The expedition arrived in early 1512, passing en route through the Lesser Sunda Islands, being the first Europeans to get there. Before reaching Banda, the explorers visited the islands of Buru

Buru (formerly spelled Boeroe, Boro, or Bouru) is the third largest island within the Maluku Islands of Indonesia. It lies between the Banda Sea to the south and Seram Sea to the north, west of Ambon and Seram islands. The island belongs to ...

, Ambon

Ambon may refer to:

Places

* Ambon Island, an island in Indonesia

** Ambon, Maluku, a city on Ambon Island, the capital of Maluku province

** Governorate of Ambon, a colony of the Dutch East India Company from 1605 to 1796

* Ambon, Morbihan, a c ...

and Seram

Seram (formerly spelled Ceram; also Seran or Serang) is the largest and main island of Maluku province of Indonesia, despite Ambon Island's historical importance. It is located just north of the smaller Ambon Island and a few other adjacent is ...

. Later, after a separation forced by a shipwreck, Abreu's vice-captain Francisco Serrão

Francisco Serrão (died 1521) was a Portuguese explorer and a possible cousin of Ferdinand Magellan. His 1512 voyage was the first known European sailing east past Malacca through modern Indonesia and the East Indies. He became a confidant of S ...

sailed to the north and, but his ship sank off Ternate

Ternate is a city in the Indonesian province of North Maluku and an island in the Maluku Islands. It was the ''de facto'' provincial capital of North Maluku before Sofifi on the nearby coast of Halmahera became the capital in 2010. It is off the ...

, where he obtained a license to build a Portuguese fortress-factory: the Forte de São João Baptista de Ternate.

Letters describing the "Spice Islands", from Serrão to Ferdinand Magellan

Ferdinand Magellan ( or ; pt, Fernão de Magalhães, ; es, link=no, Fernando de Magallanes, ; 4 February 1480 – 27 April 1521) was a Portuguese explorer. He is best known for having planned and led the 1519 Spanish expedition to the Eas ...

, who was his friend and possibly a cousin, helped Magellan persuade the Spanish crown to finance the first circumnavigation of the earth. On 6 November 1521, the Moluccas, "the cradle of all spices", were reached from the east by Magellan's fleet, sailing then under Juan Sebastián Elcano

Juan Sebastián Elcano (Elkano in modern Basque; sometimes given as ''del Cano''; 1486/1487Some sources state that he was born in 1476. Most of this sources try to make a point about him participating on a military campaign at the Mediterranean ...

, at the service of the Spanish Crown. Before Magellan and Serrão could meet in the islands, Serrão died on the island of Ternate, almost at the same time Magellan was killed in the battle of Mactan

The Battle of Mactan ( ceb, Gubot sa Mactan; fil, Labanan sa Mactan; es, Batalla de Mactán) was a fierce clash fought in the archipelago of the Philippines on April 27, 1521. The warriors of Lapulapu, one of the Datus of Mactan, overpowered ...

in the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

.

After the Magellan–Elcano expedition (1519–1522), Charles V sent a second expedition, led by García Jofre de Loaísa

García or Garcia may refer to:

People

* García (surname)

* Kings of Pamplona/Navarre

** García Íñiguez of Pamplona, king of Pamplona 851/2–882

** García Sánchez I of Pamplona, king of Pamplona 931–970

** García Sánchez II of Pam ...

, to colonise the islands, based on the assertion that they were in the Castilian zone, under the Treaty of Tordesillas.The expedition of García Jofre de Loaísa

García or Garcia may refer to:

People

* García (surname)

* Kings of Pamplona/Navarre

** García Íñiguez of Pamplona, king of Pamplona 851/2–882

** García Sánchez I of Pamplona, king of Pamplona 931–970

** García Sánchez II of Pam ...

(1525–1526) aimed to occupy and colonise the Moluccas. The fleet of seven ships and 450 men included the most notable Spanish navigators: Juan Sebastián Elcano

Juan Sebastián Elcano (Elkano in modern Basque; sometimes given as ''del Cano''; 1486/1487Some sources state that he was born in 1476. Most of this sources try to make a point about him participating on a military campaign at the Mediterranean ...

, who lost his life in this expedition, and the young Andrés de Urdaneta

Andrés de Urdaneta (1508 – June 3, 1568) was a maritime explorer for the Spanish Empire of Basque heritage, who became an Augustinian friar. At the age of seventeen, he accompanied the Loaísa expedition to the Spice Islands where he sp ...

. After some difficulties, the expedition reached Maluku Islands, docking at Tidore

Tidore ( id, Kota Tidore Kepulauan, lit. "City of Tidore Islands") is a city, island, and archipelago in the Maluku Islands of eastern Indonesia, west of the larger island of Halmahera. Part of North Maluku Province, the city includes the island ...

, where the Spanish established a fort. There was inevitable conflict with the Portuguese, who were already established in Ternate. After a year of fighting, the Spanish suffered a defeat but, despite that, nearly a decade of skirmishes over the possession of the islands ensued.

Conference of Badajoz–Elvas

In 1524, both kingdoms organised the "Junta de Badajoz–Elvas" to resolve the dispute. Each crown appointed threeastronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. They observe astronomical objects such as stars, planets, moons, comets and galaxies – in either ...

s and cartographers

Cartography (; from grc, χάρτης , "papyrus, sheet of paper, map"; and , "write") is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an i ...

, three pilots and three mathematicians, who formed a committee to establish the exact location of the antimeridian

The 180th meridian or antimeridian is the meridian 180° both east and west of the prime meridian in a geographical coordinate system. The longitude at this line can be given as either east or west.

On Earth, these two meridians form a ...

of Tordesillas, and the intention was to divide the whole world into two equal hemisphere

Hemisphere refers to:

* A half of a sphere

As half of the Earth

* A hemisphere of Earth

** Northern Hemisphere

** Southern Hemisphere

** Eastern Hemisphere

** Western Hemisphere

** Land and water hemispheres

* A half of the (geocentric) celes ...

s.

The Portuguese delegation sent by King João III included António de Azevedo Coutinho, Diogo Lopes de Sequeira

D.Diogo Lopes de Sequeira (1465–1530) was a Portuguese fidalgo, sent to analyze the trade potential in Madagascar and Malacca. He arrived at Malacca on 11 September 1509 and left the next year when he discovered that Sultan Mahmud Shah was plan ...

, and Lopo Homem

Lopo Homem (c. 1497 - c. 1572) was a 16th-century Portuguese cartographer and cosmographer based in Lisbon and best known for his work on the Miller Atlas.

Biography

Homem is estimated to have been born c. 1497, possibly into a noble family ...

, a cartographer and cosmographer

The term cosmography has two distinct meanings: traditionally it has been the protoscience of mapping the general features of the cosmos, heaven and Earth; more recently, it has been used to describe the ongoing effort to determine the large-scal ...

. The plenipotentiary

A ''plenipotentiary'' (from the Latin ''plenus'' "full" and ''potens'' "powerful") is a diplomat who has full powers—authorization to sign a treaty or convention on behalf of his or her sovereign. When used as a noun more generally, the wor ...

from Portugal was Mercurio Gâtine, and those from Spain were Count Mercurio Gâtine, Garcia de Loaysa, Bishop of Osma

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Osma-Soria ( la, Oxomen(sis)–Sorian(a)) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the Catholic Church in northern Spain. It is a suffragan diocese in the ecclesiastical province of the metropolitan ...

, and García de Padilla, grand master of the Order of Calatrava

The Order of Calatrava ( es, Orden de Calatrava, pt, Ordem de Calatrava) was one of the four Spanish military orders and the first military order founded in Castile, but the second to receive papal approval. The papal bull confirming the Orde ...

. Former Portuguese cartographer Diogo Ribeiro

Diogo Ribeiro (d. 16 August 1533) was a Portuguese cartographer and explorer who worked most of his life in Spain where he was known as Diego Ribero. He worked on the official maps of the ''Padrón Real'' (or ''Padrón General'') from 1518 to 1 ...

, was part of the Spanish delegation.The records of the committee, held in the Portuguese national archive at Torre do Tombo, include a letter written by Lopo Homem, Portuguese cartographer and cosmographer, alluding to the quarrel between the two kingdoms over the sovereign rights of each.

An amusing story is said to have taken place at this meeting. According to contemporary Castilian writer Peter Martyr d'Anghiera, a small boy stopped the Portuguese delegation and asked if they intended to divide up the world. The delegation answered that they were. The boy responded by baring his backside and suggesting that they draw their line through his butt crack.

The board met several times, at Badajoz

Badajoz (; formerly written ''Badajos'' in English) is the capital of the Province of Badajoz in the autonomous community of Extremadura, Spain. It is situated close to the Portuguese border, on the left bank of the river Guadiana. The populatio ...

and Elvas

Elvas () is a Portuguese municipality, former episcopal city and frontier fortress of easternmost central Portugal, located in the district of Portalegre in Alentejo. It is situated about east of Lisbon, and about west of the Spanish fortres ...

, without reaching an agreement. Geographic knowledge at that time was inadequate for an accurate assignment of longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east– west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek lette ...

, and each group chose maps or globes that showed the islands to be in their own hemisphere.As an example of this partiality, the chief advisor to Charles V, Jean Carondelet

Jean II Carondelet (1469 in Dôle – 7 February 1545 in Mechelen), was a Burgundian cleric, politician, jurist and one of the most important advisors to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. He was a patron of the Dutch philosopher Erasmus and ...

, possessed a globe by Franciscus Monachus

Franciscus Monachus, (c. 1490 – 1565) was born Frans Smunck in Mechelen (or Malines) in the Duchy of Brabant (in modern-day Belgium). His Latinised name, adopted when he matriculated at the University of Louvain, is translated as simply ''Franc ...

which showed the islands in the Spanish hemisphere. John III and Charles V agreed to not send anyone else to the Moluccas until it was established in whose hemisphere they were situated.

Between 1525 and 1528 Portugal sent several expeditions to the area around Maluku Islands. Gomes de Sequeira

Gomes de Sequeira was a Portuguese explorer in the early 16th century. It has been suggested by some historians that Gomes de Sequeira may have sailed to the northeast coast of Australia as part of his explorations, although this is disputed.

See ...

and Diogo da Rocha Diogo da Rocha was a captain who sailed for the Portuguese in 1525. He is credited as being the first to encounter the islands "to the Eastwards of Mindanao, and the islands of St. Lazarus" ( possibly Ulithi in the Caroline Islands

The Caro ...

were sent by the governor of Ternate Jorge de Meneses to the Celebes

Sulawesi (), also known as Celebes (), is an island in Indonesia. One of the four Greater Sunda Islands, and the world's eleventh-largest island, it is situated east of Borneo, west of the Maluku Islands, and south of Mindanao and the Sul ...

(also already visited by Simão de Abreu in 1523) and to the north. The expeditioners were the first Europeans to reach the Caroline Islands

The Caroline Islands (or the Carolines) are a widely scattered archipelago of tiny islands in the western Pacific Ocean, to the north of New Guinea. Politically, they are divided between the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) in the ce ...

, which they named "Islands de Sequeira ". Explorers such as Martim Afonso de Melo (1522-24), and possible Gomes de Sequeira (1526-1527), sighted the Aru Islands

The Aru Islands Regency ( id, Kabupaten Kepulauan Aru) is a group of about 95 low-lying islands in the Maluku Islands of eastern Indonesia. It also forms a regency of Maluku Province, with a land area of . At the 2011 Census the Regency had a ...

and the Tanimbar Islands

The Tanimbar Islands, also called ''Timur Laut'', are a group of about 65 islands in the Maluku province of Indonesia. The largest and most central of the islands is Yamdena; others include Selaru to the southwest of Yamdena, Larat and Ford ...

. In 1526 Jorge de Meneses reached northwestern Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea (abbreviated PNG; , ; tpi, Papua Niugini; ho, Papua Niu Gini), officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea ( tpi, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niugini; ho, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niu Gini), is a country i ...

, landing in Biak

Biak is an island located in Cenderawasih Bay near the northern coast of Papua, an Indonesian province, and is just northwest of New Guinea. Biak is the largest island in its small archipelago, and has many atolls, reefs, and corals.

The large ...

in the Schouten Islands

The Schouten Islands ( id, Kepulauan Biak, also Biak Islands or Geelvink Islands) are an island group of Papua province, eastern Indonesia in the Cenderawasih Bay (or Geelvink Bay) 50 km off the north-western coast of the island of New ...

, and from there he sailed to Waigeo

Waigeo is an island in Southwest Papua province of eastern Indonesia. The island is also known as Amberi, or Waigiu. It is the largest of the four main islands in the Raja Ampat Islands archipelago, between Halmahera and about to the north-w ...

on the Bird's Head Peninsula

The Bird's Head Peninsula ( Indonesian: ''Kepala Burung'', nl, Vogelkop) or Doberai Peninsula (''Semenanjung Doberai''), is a large peninsula that makes up the northwest portion of the island of New Guinea, comprising the Indonesian provinces ...

.

On the other hand, in addition to the Loaísa expedition from Spain to the Moluccas (1525-1526), the Castilians sent an expedition there via the Pacific, led by Álvaro de Saavedra Cerón

Álvaro de Saavedra Cerón (often written as Álvaro de Saavedra) (d. 1529) was one of the Spanish explorers in the Pacific Ocean. The exact date and place of his birth are unknown, but he was born in the late 15th century or early 16th century in ...

(1528) (prepared by Hernán Cortés in Mexico), in order to compete with the Portuguese in the region. Members of the Garcia Jofre de Loaísa expedition were taken prisoner by the Portuguese, who returned the survivors to Europe by the western route. Álvaro de Saavedra Cerón reached the Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands ( mh, Ṃajeḷ), officially the Republic of the Marshall Islands ( mh, Aolepān Aorōkin Ṃajeḷ),'' () is an independent island country and microstate near the Equator in the Pacific Ocean, slightly west of the Intern ...

, and in two failed attempts to return from Maluku Islands via the Pacific, explored part of west and northern New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torr ...

, also reaching the Schouten Islands

The Schouten Islands ( id, Kepulauan Biak, also Biak Islands or Geelvink Islands) are an island group of Papua province, eastern Indonesia in the Cenderawasih Bay (or Geelvink Bay) 50 km off the north-western coast of the island of New ...

and sighting Yapen

Yapen (also Japan, Jobi) is an island of Papua, Indonesia. The Yapen Strait separates Yapen and the Biak Islands to the north. It is in Cenderawasih Bay off the north-western coast of the island of New Guinea. To the west is Mios Num Island ...

, as well as the Admiralty Islands

The Admiralty Islands are an archipelago group of 18 islands in the Bismarck Archipelago, to the north of New Guinea in the South Pacific Ocean. These are also sometimes called the Manus Islands, after the largest island.

These rainforest-co ...

and the Carolines.

On 10 February 1525, Charles V's younger sister Catherine of Austria married John III of Portugal, and on 11 March 1526, Charles V married king John's sister Isabella of Portugal. These crossed weddings strengthened the ties between the two crowns, facilitating an agreement regarding the Moluccas. It was in the interests of the emperor to avoid conflict, so that he could focus on his European policy, and the Spaniards did not know then how to get spices from the Maluku Islands to Europe via the eastern route. The Manila-Acapulco route was only established by Andrés de Urdaneta in 1565.

Treaty

The Treaty of Zaragoza laid down that the eastern border between the two domain zones was leagues (1,763 kilometres, 952 nautical miles), or 17° east, of the Maluku Islands. This left the islands within the Portuguese domain. In exchange, the King of Portugal paid Emperor Charles V 350,000gold ducats

The ducat () coin was used as a trade coin in Europe from the later Middle Ages from the 13th to 19th centuries. Its most familiar version, the gold ducat or sequin containing around of 98.6% fine gold, originated in Venice in 1284 and gained wi ...

. The treaty included a safeguard clause which stated that the deal would be undone if at any time the emperor wished to revoke it, with the Portuguese being reimbursed the money they had to pay, and each nation "will have the right and the action as that is now." That never happened however, because the emperor desperately needed the Portuguese money to finance the War of the League of Cognac

The War of the League of Cognac (1526–30) was fought between the Habsburg dominions of Charles V—primarily the Holy Roman Empire and Spain—and the League of Cognac, an alliance including the Kingdom of France, Pope Clement VII, the Repub ...

against his archrival Francis I of France

Francis I (french: François Ier; frm, Francoys; 12 September 1494 – 31 March 1547) was King of France from 1515 until his death in 1547. He was the son of Charles, Count of Angoulême, and Louise of Savoy. He succeeded his first cousin on ...

.

The treaty did not clarify or modify the line of demarcation established by the Treaty of Tordesillas, nor did it validate Spain's claim to equal hemisphere

Hemisphere refers to:

* A half of a sphere

As half of the Earth

* A hemisphere of Earth

** Northern Hemisphere

** Southern Hemisphere

** Eastern Hemisphere

** Western Hemisphere

** Land and water hemispheres

* A half of the (geocentric) celes ...

s (180° each), so the two lines divided the Earth into unequal portions. Portugal's portion was roughly 191° of the Earth's circumference, whereas Spain's portion was roughly 169°. There was a ±4° margin of uncertainty as to the exact size of both portions, due to the variation of opinion about the precise location of the Tordesillas line.

Under the treaty, Portugal gained control of all lands and seas west of the line, including all of Asia and its neighbouring islands so far "discovered", leaving Spain with most of the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contin ...

. Although the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

was not mentioned in the treaty, Spain implicitly relinquished any claim to it because it was well west of the line. Nevertheless, by 1542, King Charles V had decided to colonise the Philippines, assuming that Portugal would not protest too vigorously because the archipelago had no spices. Although he failed in his attempt, King Philip II succeeded in 1565, establishing the initial Spanish trading post at Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populate ...

. As his father had expected, there was little opposition from the Portuguese.

In later times, Portuguese colonization in Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

during the Iberian Union

pt, União Ibérica

, conventional_long_name =Iberian Union

, common_name =

, year_start = 1580

, date_start = 25 August

, life_span = 1580–1640

, event_start = War of the Portuguese Succession

, event_end = Portuguese Restoration War

, ...

extended far west of the line defined in the Treaty of Tordesillas and into what would have been Spanish territory under the treaty, later on new limits were drawn in the Treaty of Madrid (13 January 1750)

The Spanish–Portuguese treaty of 1750 or Treaty of Madrid was a document signed in the Spanish capital by Ferdinand VI of Spain and John V of Portugal on 13 January 1750.

The agreement aimed to end armed conflict over a border dispute betwee ...

stablishing the current limits of Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

.

See also

*141st meridian east

The 141st meridian east of Greenwich is a line of longitude that extends from the North Pole across the Arctic Ocean, Asia, the Pacific Ocean, Australasia, the Indian Ocean, the Southern Ocean, and Antarctica to the South Pole.

The 141st meri ...

* Indonesia–Papua New Guinea relations

* South Australia–Victoria border dispute

....

Notes

References

External links

Transcription of the Spanish-language version of the Treaty

by Cristóbal Bernal * Yasuo Miyakawa

"The changing iconography of Japanese political geography,"

''GeoJournal,'' Vol. 52, No. 4, Iconographies (2000), pp. 345–352. {{Authority control History of the Philippines (1565–1898) Meridians (geography) Geopolitical rivalry

Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. It lies by the Ebro river and its tributari ...

Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. It lies by the Ebro river and its tributari ...

Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. It lies by the Ebro river and its tributari ...

Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. It lies by the Ebro river and its tributari ...

Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. It lies by the Ebro river and its tributari ...

Portugal–Spain relations

1529 in Spain

1529 in Portugal

1529 treaties

Portuguese colonisation in Asia

Spanish exploration in the Age of Discovery