Treaty of Waitangi on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Treaty of Waitangi ( mi, Te Tiriti o Waitangi) is a document of central importance to the

Māori generally respected the British, partially due to their relationships with missionaries and also due to British status as a major maritime power, which had been made apparent to Māori travelling outside New Zealand. The other major powers in the area around the 1830s included American whalers, whom the Māori accepted as cousins of the British, and French Catholics who came for trade and as missionaries. The Māori were still deeply distrustful of the French, due to a massacre of 250 people that had occurred in 1772, when they retaliated for the killing of

Māori generally respected the British, partially due to their relationships with missionaries and also due to British status as a major maritime power, which had been made apparent to Māori travelling outside New Zealand. The other major powers in the area around the 1830s included American whalers, whom the Māori accepted as cousins of the British, and French Catholics who came for trade and as missionaries. The Māori were still deeply distrustful of the French, due to a massacre of 250 people that had occurred in 1772, when they retaliated for the killing of  Hobson was called to the Colonial Office on the evening of 14 August 1839 and given instructions to take the constitutional steps needed to establish a British colony. He was appointed

Hobson was called to the Colonial Office on the evening of 14 August 1839 and given instructions to take the constitutional steps needed to establish a British colony. He was appointed

Without a draft document prepared by lawyers or Colonial Office officials, Hobson was forced to write his own treaty with the help of his secretary, James Freeman, and British Resident

Without a draft document prepared by lawyers or Colonial Office officials, Hobson was forced to write his own treaty with the help of his secretary, James Freeman, and British Resident

For Māori chiefs, the signing at Waitangi would have needed a great deal of trust. Nonetheless, the expected benefits of British protection must have outweighed their fears. In particular, the French were also interested in New Zealand, and there were fears that if they did not side with the British that the French would put pressure on them in a similar manner to that of other Pacific Islanders farther north in what would become

For Māori chiefs, the signing at Waitangi would have needed a great deal of trust. Nonetheless, the expected benefits of British protection must have outweighed their fears. In particular, the French were also interested in New Zealand, and there were fears that if they did not side with the British that the French would put pressure on them in a similar manner to that of other Pacific Islanders farther north in what would become

In July 1860, during the conflicts, Governor Thomas Gore Browne convened a group of some 200 Māori (including over 100 pro-Crown chiefs handpicked by officials) to discuss the treaty and land for a month at Mission Bay, Kohimarama, Auckland. This became known as the Kohimarama Conference, and was an attempt to prevent the spread of fighting to other regions of New Zealand. But many of the chiefs present were critical of the Crown's handling of the Taranaki conflict. Those at the conference reaffirmed the treaty and the Queen's sovereignty and suggested that a native council be established, but this did not occur.

In July 1860, during the conflicts, Governor Thomas Gore Browne convened a group of some 200 Māori (including over 100 pro-Crown chiefs handpicked by officials) to discuss the treaty and land for a month at Mission Bay, Kohimarama, Auckland. This became known as the Kohimarama Conference, and was an attempt to prevent the spread of fighting to other regions of New Zealand. But many of the chiefs present were critical of the Crown's handling of the Taranaki conflict. Those at the conference reaffirmed the treaty and the Queen's sovereignty and suggested that a native council be established, but this did not occur.

Legislation after the State Owned Enterprises case has followed suit in giving the treaty an increased legal importance. In ''New Zealand Maori Council v Attorney General'' (1990) the case concerned FM radio frequencies and found that the treaty could be relevant even concerning legislation which did not mention it and that even if references to the treaty were removed from legislation, the treaty may still be legally relevant. Examples include the ownership of the radio spectrum and the protection of the

Legislation after the State Owned Enterprises case has followed suit in giving the treaty an increased legal importance. In ''New Zealand Maori Council v Attorney General'' (1990) the case concerned FM radio frequencies and found that the treaty could be relevant even concerning legislation which did not mention it and that even if references to the treaty were removed from legislation, the treaty may still be legally relevant. Examples include the ownership of the radio spectrum and the protection of the

Information about the treaty

at nzhistory.net.nz

Treaty of Waitangi site

at archives New Zealand

Comic book explaining the treaty

used in New Zealand schools {{DEFAULTSORT:Treaty of Waitangi 1840 in New Zealand Constitution of New Zealand Government of New Zealand Māori history Māori politics Race relations in New Zealand Memory of the World Register 1840 treaties Aboriginal title in New Zealand Treaties of the United Kingdom (1801–1922) Treaties of New Zealand Treaties of the Colony of New Zealand Treaties with indigenous peoples Bay of Islands February 1840 events

history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as well ...

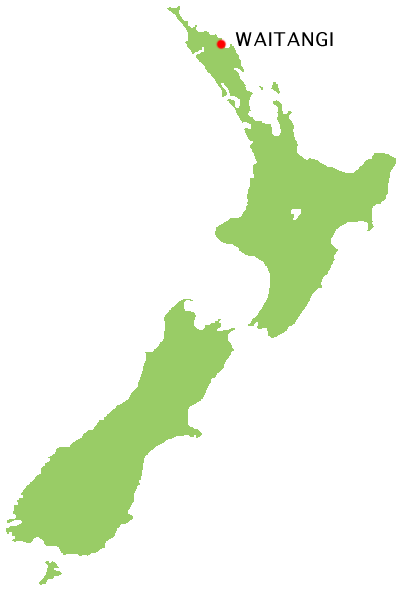

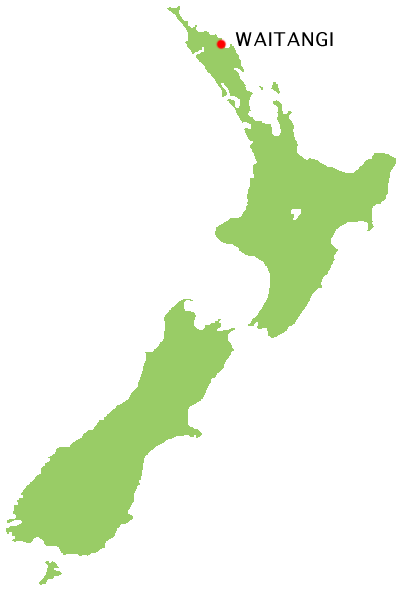

, to the political constitution of the state, and to the national mythos of New Zealand. It has played a major role in the treatment of the Māori population in New Zealand, by successive governments and the wider population, a role that has been especially prominent from the late 20th century. The treaty document is an agreement, not a treaty as recognised in international law and it has no independent legal status, being legally effective only to the extent it is recognised in various statutes. It was first signed on 6 February 1840 by Captain William Hobson

Captain William Hobson (26 September 1792 – 10 September 1842) was a British Royal Navy officer who served as the first Governor of New Zealand. He was a co-author of the Treaty of Waitangi.

Hobson was dispatched from London in July 1 ...

as consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throu ...

for the British Crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, partic ...

and by Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the Co ...

chiefs () from the North Island

The North Island, also officially named Te Ika-a-Māui, is one of the two main islands of New Zealand, separated from the larger but much less populous South Island by the Cook Strait. The island's area is , making it the world's 14th-larges ...

of New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

.

The treaty was written at a time when the New Zealand Company

The New Zealand Company, chartered in the United Kingdom, was a company that existed in the first half of the 19th century on a business model focused on the systematic colonisation of New Zealand. The company was formed to carry out the principl ...

, acting on behalf of large numbers of settlers and would-be settlers, were establishing a colony

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state' ...

in New Zealand, and when some Māori leaders had petitioned the British for protection against French ambitions. It was drafted with the intention of establishing a British Governor of New Zealand

The governor-general of New Zealand ( mi, te kāwana tianara o Aotearoa) is the viceregal representative of the monarch of New Zealand, currently King Charles III. As the King is concurrently the monarch of 14 other Commonwealth realms and l ...

, recognising Māori ownership of their lands, forests and other possessions, and giving Māori the rights of British subject

The term "British subject" has several different meanings depending on the time period. Before 1949, it referred to almost all subjects of the British Empire (including the United Kingdom, Dominions, and colonies, but excluding protectorates ...

s. It was intended by the British Crown to ensure that when Lieutenant Governor Hobson subsequently made the declaration of British sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

over New Zealand in May 1840, the Māori people would not feel that their rights had been ignored. Once it had been written and translated, it was first signed by Northern Māori leaders at Waitangi. Copies were subsequently taken around New Zealand and over the following months many other chiefs signed. Around 530 to 540 Māori, at least 13 of them women, signed the Māori language version of the Treaty of Waitangi, despite some Māori leader

Leadership, both as a research area and as a practical skill, encompasses the ability of an individual, group or organization to "lead", influence or guide other individuals, teams, or entire organizations. The word "leadership" often gets v ...

s cautioning against it. Only 39 signed the English version. pp 159 An immediate result of the treaty was that Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

's government gained the sole right to purchase land. In total there are nine signed copies of the Treaty of Waitangi, including the sheet signed on 6 February 1840 at Waitangi.

The text of the treaty includes a preamble and three articles. It is bilingual, with the Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the Co ...

text translated in the context of the time from the English.

* Article one of the Māori text grants governance rights to the Crown while the English text cedes "all rights and powers of sovereignty" to the Crown.

* Article two of the Māori text establishes that Māori will retain full chieftainship over their lands, villages and all their treasures while the English text establishes the continued ownership of the Māori over their lands and establishes the exclusive right of pre-emption of the Crown.

* Article three gives Māori people full rights and protections as British subjects.

As some words in the English treaty did not translate directly into the written Māori language

Māori (), or ('the Māori language'), also known as ('the language'), is an Eastern Polynesian language spoken by the Māori people, the indigenous population of mainland New Zealand. Closely related to Cook Islands Māori, Tuamotuan, and ...

of the time, the Māori text is not an exact translation of the English text, particularly in relation to the meaning of having and ceding sovereignty. pp 20-116 These differences created disagreements in the decades following the signing, eventually contributing to the New Zealand Wars

The New Zealand Wars took place from 1845 to 1872 between the New Zealand colonial government and allied Māori on one side and Māori and Māori-allied settlers on the other. They were previously commonly referred to as the Land Wars or the M ...

of 1845 to 1872 and continuing through to the Treaty of Waitangi settlements

Claims and settlements under the Treaty of Waitangi have been a significant feature of New Zealand politics since the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975 and the Waitangi Tribunal that was established by that act to hear claims. Successive governments ...

starting in the early 1990s.

During the second half of the 19th century Māori generally lost control of much of the land they had owned, sometimes through legitimate sale, but often due to unfair land-deals, settlers occupying land that had not been sold, or through outright confiscations in the aftermath of the New Zealand Wars. In the period following the New Zealand Wars, the New Zealand government mostly ignored the treaty, and a court-case judgement in 1877 declared it to be "a simple nullity". Beginning in the 1950s, Māori increasingly sought to use the treaty as a platform for claiming additional rights to sovereignty and to reclaim lost land, and governments in the 1960s and 1970s responded to these arguments, giving the treaty an increasingly central role in the interpretation of land rights and relations between Māori people and the state. In 1975 the New Zealand Parliament passed the Treaty of Waitangi Act, establishing the Waitangi Tribunal as a permanent commission of inquiry tasked with interpreting the treaty, researching breaches of the treaty by the Crown or its agents, and suggesting means of redress. In most cases, recommendations of the Tribunal are not binding on the Crown, but settlements totalling almost $1 billion have been awarded to various Māori groups. Various legislation passed in the latter part of the 20th century has made reference to the treaty, which has led to ad hoc incorporation of the treaty in law. As a result, the treaty has now become widely regarded as the founding document of New Zealand.

The New Zealand government established Waitangi Day

Waitangi Day ( mi, Te Rā o Waitangi), the national day of New Zealand, marks the anniversary of the initial signing – on 6 February 1840 – of the Treaty of Waitangi, which is regarded as the founding document of the nation. The first Wai ...

as a national holiday in 1974; each year the holiday commemorates the date of the signing of the treaty.

Early history

The first contact between the Māori and Europeans was in 1642, when Dutch explorerAbel Tasman

Abel Janszoon Tasman (; 160310 October 1659) was a Dutch seafarer, explorer, and merchant, best known for his voyages of 1642 and 1644 in the service of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). He was the first known European explorer to reach New ...

arrived and was fought off, and again in 1769 when the English navigator Captain James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean and ...

claimed New Zealand for Britain at the Mercury Islands

The Mercury Islands are a group of seven islands off the northeast coast of New Zealand's North Island. They are located off the coast of the Coromandel Peninsula, and northeast of the town of Whitianga.

History

The Ngāti Karaua (a hapu of ...

. Nevertheless, the British government showed little interest in following up this claim for over half a century. The first mention of New Zealand in British statutes is in the Murders Abroad Act of 1817, which clarified that New Zealand was not a British colony (despite being claimed by Captain Cook) and "not within His Majesty's dominions". Between 1795 and 1830 a steady flow of sealing and then whaling ships visited New Zealand, mainly stopping at the Bay of Islands

The Bay of Islands is an area on the east coast of the Far North District of the North Island of New Zealand. It is one of the most popular fishing, sailing and tourist destinations in the country, and has been renowned internationally for it ...

for food supplies and recreation. Many of the ships came from Sydney. Trade between Sydney and New Zealand increased as traders sought kauri

''Agathis'', commonly known as kauri or dammara, is a genus of 22 species of evergreen tree. The genus is part of the ancient conifer family Araucariaceae, a group once widespread during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, but now largely res ...

timber and flax and missionaries purchased large areas of land in the Bay of Islands. This trade was seen as mutually advantageous, and Māori tribes competed for access to the services of Europeans that had chosen to live on the islands because they brought goods and knowledge that were essential to the local tribe (). At the same time, Europeans living in New Zealand needed the protection that Māori chiefs could provide. As a result of trade, Māori society changed drastically up to the 1840s. They changed their society from one of subsistence farming and gathering to cultivating useful trade crops.

While heading the parliamentary campaign against the British slave trade for twenty years until the passage of the Slave Trade Act of 1807

The Slave Trade Act 1807, officially An Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom prohibiting the slave trade in the British Empire. Although it did not abolish the practice of slavery, it ...

, William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 175929 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist and leader of the movement to abolish the slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780, eventually becom ...

championed the foundation of the Church Missionary Society

The Church Mission Society (CMS), formerly known as the Church Missionary Society, is a British mission society working with the Christians around the world. Founded in 1799, CMS has attracted over nine thousand men and women to serve as mission ...

(CMS) in 1799, with other members of the Clapham Sect

The Clapham Sect, or Clapham Saints, were a group of social reformers associated with Clapham in the period from the 1780s to the 1840s. Despite the label "sect", most members remained in the established (and dominant) Church of England, which ...

including John Venn

John Venn, Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS, Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London, FSA (4 August 1834 – 4 April 1923) was an English mathematician, logician and philosopher noted for introducing Venn diagrams, which are used in l ...

, determined to improve the treatment of indigenous people by the British. This led to the establishment of their Christian mission in New Zealand, which saw laymen arriving from 1814 to teach building, farming and Christianity to Māori, as well as training 'native' ministers. The Māori language

Māori (), or ('the Māori language'), also known as ('the language'), is an Eastern Polynesian language spoken by the Māori people, the indigenous population of mainland New Zealand. Closely related to Cook Islands Māori, Tuamotuan, and ...

did not then have an indigenous writing system. Missionaries learned to speak Māori, and introduced the Latin alphabet. The CMS, including Thomas Kendall

Thomas Kendall (13 December 1778 – 6 August 1832) was a New Zealand missionary, recorder of the Māori language, schoolmaster, arms dealer, and Pākehā Māori.

Early life: Lincolnshire and London, 1778–1813

A younger son of farmer Ed ...

; Māori, including Tītore

Tītore (circa 1775-1837) (sometimes known as Tītore Tākiri) was a Rangatira (chief) of the Ngāpuhi iwi (tribe). He was a war leader of the Ngāpuhi who lead the war expedition against the Māori tribes at East Cape in 1820 and 1821. He also ...

and Hongi Hika

Hongi Hika ( – 6 March 1828) was a New Zealand Māori rangatira (chief) and war leader of the iwi of Ngāpuhi. He was a pivotal figure in the early years of regular European contact and settlement in New Zealand. As one of the first Māor ...

; and Cambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

's Samuel Lee, developed the written language between 1817 and 1830. In 1833, while living in the Paihia mission house of Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

priest and the now head of the New Zealand CMS mission (later to become the New Zealand Church Missionary Society

The New Zealand Church Missionary Society is a mission society working within the Anglican Communion and Protestant, Evangelical Anglicanism. The parent organisation was founded in England in 1799. The Church Missionary Society (CMS) sent missiona ...

) Rev Henry Williams, missioner William Colenso published the Māori translations of books of the Bible, the first books printed in New Zealand. His 1837 Māori New Testament was the first indigenous language translation of the Bible published in the southern hemisphere. Demand for the Māori New Testament, and the Prayer Book that followed, grew exponentially, as did Christian Māori leadership and public Christian services, with 33,000 Māori soon attending regularly. Literacy and understanding the Bible increased and social and economic benefits, decreased slavery and intertribal violence, and increased peace and respect for all people in Māori society, including women.

Māori generally respected the British, partially due to their relationships with missionaries and also due to British status as a major maritime power, which had been made apparent to Māori travelling outside New Zealand. The other major powers in the area around the 1830s included American whalers, whom the Māori accepted as cousins of the British, and French Catholics who came for trade and as missionaries. The Māori were still deeply distrustful of the French, due to a massacre of 250 people that had occurred in 1772, when they retaliated for the killing of

Māori generally respected the British, partially due to their relationships with missionaries and also due to British status as a major maritime power, which had been made apparent to Māori travelling outside New Zealand. The other major powers in the area around the 1830s included American whalers, whom the Māori accepted as cousins of the British, and French Catholics who came for trade and as missionaries. The Māori were still deeply distrustful of the French, due to a massacre of 250 people that had occurred in 1772, when they retaliated for the killing of Marion du Fresne

Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne (22 May 1724 – 12 June 1772) was a French privateer, East India captain and explorer. The expedition he led to find the hypothetical ''Terra Australis'' in 1771 made important geographic discoveries in the sout ...

and some of his crew. While the threat of the French never materialised, in 1831 it prompted thirteen major chiefs from the far north of the country to meet at Kerikeri

Kerikeri () is the largest town in Northland, New Zealand. It is a tourist destination north of Auckland and north of the northern region's largest city, Whangarei. It is sometimes called the Cradle of the Nation, as it was the site of ...

to compose a letter to King William IV asking for Britain to be a "friend and guardian" of New Zealand. It is the first known plea for British intervention written by Māori. In response, the British government sent James Busby

James Busby (7 February 1802 – 15 July 1871) was the British Resident in New Zealand from 1833 to 1840. He was involved in drafting the 1835 Declaration of the Independence of New Zealand and the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi. As British Resident, ...

in 1832 to be the British Resident in New Zealand. In 1834 Busby drafted a document known as the Declaration of the Independence of New Zealand, He Whakaputanga which he and 35 northern Māori chiefs signed at Waitangi on 28 October 1835, establishing those chiefs as representatives of a proto-state under the title of the "United Tribes of New Zealand

The United Tribes of New Zealand ( mi, Te W(h)akaminenga o Ngā Rangatiratanga o Ngā Hapū o Nū Tīreni, lit=) was a confederation of Māori tribes based in the north of the North Island, existing legally from 1835 to 1840. It received dipl ...

". This document was not well received by the Colonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created to deal with the colonial affairs of British North America but required also to oversee the increasing number of c ...

in Britain, and it was decided that a new policy for New Zealand was needed. From a Māori perspective, The Declaration of Independence, was twofold, one for the British to establish control of its lawless subjects in New Zealand, and two, to establish internationally the mana

According to Melanesian and Polynesian mythology, ''mana'' is a supernatural force that permeates the universe. Anyone or anything can have ''mana''. They believed it to be a cultivation or possession of energy and power, rather than being ...

and sovereignty of Māori leaders.

From May to July 1836, Royal Navy officer Captain William Hobson

Captain William Hobson (26 September 1792 – 10 September 1842) was a British Royal Navy officer who served as the first Governor of New Zealand. He was a co-author of the Treaty of Waitangi.

Hobson was dispatched from London in July 1 ...

, under instruction from Governor of New South Wales

The governor of New South Wales is the viceregal representative of the Australian monarch, King Charles III, in the state of New South Wales. In an analogous way to the governor-general of Australia at the national level, the governors of the A ...

Sir Richard Bourke

General Sir Richard Bourke, KCB (4 May 1777 – 12 August 1855), was an Irish-born British Army officer who served as Governor of New South Wales from 1831 to 1837. As a lifelong Whig (Liberal), he encouraged the emancipation of convicts and ...

, visited New Zealand to investigate claims of lawlessness in its settlements. Hobson recommended in his report that British sovereignty be established over New Zealand, in small pockets similar to the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business di ...

in Canada. Hobson's report was forwarded to the Colonial Office. From April to May 1838, the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

held a select committee Select committee may refer to:

*Select committee (parliamentary system) A select committee is a committee made up of a small number of parliamentary members appointed to deal with particular areas or issues originating in the Westminster system o ...

into the "State of the Islands of New Zealand". The New Zealand Association

The New Zealand Company, chartered in the United Kingdom, was a company that existed in the first half of the 19th century on a business model focused on the systematic colonisation of New Zealand. The company was formed to carry out the principl ...

(later the New Zealand Company

The New Zealand Company, chartered in the United Kingdom, was a company that existed in the first half of the 19th century on a business model focused on the systematic colonisation of New Zealand. The company was formed to carry out the principl ...

), missionaries, Joel Samuel Polack

Joel Samuel Polack (28 March 1807 – 17 April 1882) was an English-born New Zealand and American businessman and writer. He was one of the first Jewish settlers in New Zealand, arriving in 1831. He is regarded as an authority on pre-colonial New ...

, and the Royal Navy made submissions to the committee.

On 15 June 1839 new Letters Patent

Letters patent ( la, litterae patentes) ( always in the plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, president or other head of state, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, tit ...

were issued to expand the territory of New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

to include the entire territory of New Zealand, from latitude 34° South to 47° 10' South, and from longitude 166° 5' East to 179° East. Governor of New South Wales George Gipps

Sir George Gipps (23 December 1790 – 28 February 1847) was the Governor of the British colony of New South Wales for eight years, between 1838 and 1846. His governorship oversaw a tumultuous period where the rights to land were bitterly conte ...

was appointed Governor over New Zealand. This was the first clear expression of British intent to annex New Zealand.

Hobson was called to the Colonial Office on the evening of 14 August 1839 and given instructions to take the constitutional steps needed to establish a British colony. He was appointed

Hobson was called to the Colonial Office on the evening of 14 August 1839 and given instructions to take the constitutional steps needed to establish a British colony. He was appointed Consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throu ...

to New Zealand and was instructed to negotiate a voluntary transfer of sovereignty from the Māori to the British Crown as the House of Lords select committee had recommended in 1837. Normanby gave Hobson three instructions – to seek a cession of sovereignty, to assume complete control over land matters, and to establish a form of civil government, but he did not provide a draft of the treaty. Normanby wrote at length about the need for British intervention as essential to protect Māori interests, but this was somewhat deceptive. Hobson's instructions gave no provision for Māori government of any kind nor any Māori involvement in the administrative structure of the new colony. His instructions required him to:

treat with the Aborigines of New Zealand for the recognition of Her Majesty's Sovereign authority over the whole or any part of those islands which they may be willing to place under Her Majesty's dominion.Historian

Claudia Orange

Dame Claudia Josepha Orange (née Bell, born 17 April 1938) is a New Zealand historian best known for her 1987 book ''The Treaty of Waitangi'', which won 'Book of the Year' at the Goodman Fielder Wattie Book Award in 1988.

Since 2013 she has ...

argues that prior to 1839 the Colonial Office had initially planned a "Māori New Zealand" in which European settlers would be accommodated without a full colony where Māori might retain ownership and authority over much of the land and cede some land to settlers as part of a colony governed by the Crown. Normanby's instructions in 1839 show that the Colonial Office had shifted their stance toward colonisation and "a settler New Zealand in which a place had to be kept for Māori", primarily due to pressure from increasing numbers of British colonists, and the prospect of a private enterprise in the form of the New Zealand Company colonising New Zealand outside of the British Crown's jurisdiction. The Colonial Office was forced to accelerate its plans because of both the New Zealand Company's hurried dispatch of the ''Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

'' to New Zealand on 12 May 1839 to purchase land, and plans by French Captain Jean François L'Anglois to establish a French colony in Akaroa

Akaroa is a small town on Banks Peninsula in the Canterbury Region of the South Island of New Zealand, situated within a harbour of the same name. The name Akaroa is Kāi Tahu Māori for "Long Harbour", which would be spelled in standard ...

. After examining Colonial Office documents and correspondence (both private and public) of those who developed the policies that led to the development of the treaty, historian Paul Moon

Evan Paul Moon (born 18 October 1968) is a New Zealand historian and a professor at the Auckland University of Technology. He is a writer of New Zealand history and biography, specialising in Māori history, the Treaty of Waitangi and the ear ...

similarly argues that Treaty was not envisioned with deliberate intent to assert sovereignty over Māori, but that the Crown originally only intended to apply rule over British subjects living in the fledgling colony, and these rights were later expanded by subsequent governors through perceived necessity.

Hobson left London on 15 August 1839 and was sworn in as Lieutenant-Governor in Sydney on 14 January, finally arriving in the Bay of Islands on 29 January 1840. Meanwhile, a second New Zealand Company ship, the ''Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

'', had arrived in Port Nicholson

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Ha ...

on 3 January 1840 with a survey party to prepare for settlement. The ''Aurora

An aurora (plural: auroras or aurorae), also commonly known as the polar lights, is a natural light display in Earth's sky, predominantly seen in high-latitude regions (around the Arctic and Antarctic). Auroras display dynamic patterns of bri ...

'', the first ship carrying immigrants, arrived on 22 January.

On 30 January 1840 Hobson attended the Christ Church at Kororareka (Russell) where he publicly read a number of proclamations. The first was the Letters Patent

Letters patent ( la, litterae patentes) ( always in the plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, president or other head of state, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, tit ...

1839, in relation to the extension of the boundaries of New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

to include the islands of New Zealand. The second was in relation to Hobson's own appointment as Lieutenant-Governor of New Zealand. The third was in relation to land transactions (notably on the issue of pre-emption).

CMS printer William Colenso created a Māori circular for the United Tribes high chiefs inviting them to meet'' 'Rangatira' ''Hobson on 5 February at Busby's Waitangi home.

Drafting and translating the treaty

Without a draft document prepared by lawyers or Colonial Office officials, Hobson was forced to write his own treaty with the help of his secretary, James Freeman, and British Resident

Without a draft document prepared by lawyers or Colonial Office officials, Hobson was forced to write his own treaty with the help of his secretary, James Freeman, and British Resident James Busby

James Busby (7 February 1802 – 15 July 1871) was the British Resident in New Zealand from 1833 to 1840. He was involved in drafting the 1835 Declaration of the Independence of New Zealand and the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi. As British Resident, ...

, neither of whom was a lawyer. Historian Paul Moon

Evan Paul Moon (born 18 October 1968) is a New Zealand historian and a professor at the Auckland University of Technology. He is a writer of New Zealand history and biography, specialising in Māori history, the Treaty of Waitangi and the ear ...

believes certain articles of the treaty resemble the Treaty of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vacant throne ...

(1713), the British Sherbro Agreement (1825) and the treaty between Britain and Soombia Soosoos (1826).

The entire Treaty was prepared in three days, in which it underwent many revisions. There were doubts even during the drafting process that the Māori chiefs would be able to understand the concept of relinquishing "sovereignty".

Assuming that a treaty in English could not be understood, debated or agreed to by Māori, Hobson asked CMS head missioner Henry Williams, and his son Edward Marsh Williams, who was a scholar in Māori language and custom, to translate the document overnight on 4 February. Henry Williams was concerned with the actions of the New Zealand Company in Wellington and felt he had to agree with Hobson's request to ensure the treaty would be as favourable as possible to Māori. Williams avoided using any English words that had no expression in Māori "thereby preserving entire the spirit and tenor" of the treaty. He added a note to the copy Hobson sent to Gibbs stating, "I certify that the above is as literal a translation of the Treaty of Waitangi as the idiom of the language will allow."

The gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message (" the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words a ...

-based literacy of Māori meant some of the concepts communicated in the translation were from the Māori Bible, including (governorship) and (chiefly rule), and the idea of the treaty as a "covenant" was biblical.

The translation of the treaty was reviewed by James Busby, and he proposed the substitution of the word for , to describe the "Confederation" or gathering of the chiefs. This no doubt was a reference to the northern confederation of chiefs with whom Hobson preferred to negotiate, who eventually made up the vast majority of signatories to the treaty. Hobson believed that elsewhere in the country the Crown could exercise greater freedom over the rights of "first discoverers", which proved unwise as it led to future difficulties with other tribes in the South Island.

Debate and signing

Overnight on the 4–5 February the original English version of the treaty was translated into Māori. On the morning of 5 February the Māori and English versions of the treaty were put before a gathering () of northern chiefs inside a large marquee on the lawn in front of Busby's house at Waitangi. Hobson read the treaty aloud in English and Williams read the Māori translation and explained each section and warned the chiefs not to rush to decide whether to sign. Building on Biblical understanding, he said: Māori chiefs then debated the treaty for five hours, much of which was recorded and translated by the Paihia missionary station printer, William Colenso. Rewa, a Catholic chief, who had been influenced by the French Catholic Bishop Pompallier, said "The Māori people don't want a governor! We aren't European. It's true that we've sold some of our lands. But this country is still ours! We chiefs govern this land of our ancestors".Moka 'Kainga-mataa'

Moka Kainga-mataa e Kaingamataa/Te Kaingamata/Te Kainga-mata/Te Kainga-mataa'' (1790s–1860s) was a Māori rangatira (chief) of the Ngā Puhi iwi from Northland in New Zealand. He was distinguished in war and an intelligent participant in the ...

argued that all land unjustly purchased by Europeans should be returned. Whai asked: "Yesterday I was cursed by a white man. Is that the way things are going to be?". Protestant Chiefs such as Hōne Heke

Hōne Wiremu Heke Pōkai ( 1807/1808 – 7 August 1850), born Heke Pōkai and later often referred to as Hōne Heke, was a highly influential Māori rangatira (chief) of the Ngāpuhi iwi (tribe) and a war leader in northern New Zealand; he wa ...

, Pumuka, Te Wharerahi

Te Wharerahi (born c. 1770) was a highly respected ''rangatira'' (chief) of the Ipipiri (Bay of Islands) area of New Zealand.

Origins and mana

Aside from other connections, he was Ngati Tautahi. His mother was Te Auparo and his father Te Ma ...

, Tāmati Wāka Nene and his brother Eruera Maihi Patuone were accepting of the Governor. Hōne Heke said:

Tāmati Wāka Nene said to the chiefs:

Bishop Pompallier, who had been counselling the many Catholic Māori in the north concerning the treaty, urged them to be very wary of the treaty and not to sign anything.

For Māori chiefs, the signing at Waitangi would have needed a great deal of trust. Nonetheless, the expected benefits of British protection must have outweighed their fears. In particular, the French were also interested in New Zealand, and there were fears that if they did not side with the British that the French would put pressure on them in a similar manner to that of other Pacific Islanders farther north in what would become

For Māori chiefs, the signing at Waitangi would have needed a great deal of trust. Nonetheless, the expected benefits of British protection must have outweighed their fears. In particular, the French were also interested in New Zealand, and there were fears that if they did not side with the British that the French would put pressure on them in a similar manner to that of other Pacific Islanders farther north in what would become French Polynesia

)Territorial motto: ( en, "Great Tahiti of the Golden Haze")

, anthem =

, song_type = Regional anthem

, song = "Ia Ora 'O Tahiti Nui"

, image_map = French Polynesia on the globe (French Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of French ...

. Most importantly, Māori leaders trusted CMS missionary advice and their explanation of the treaty. The missionaries had explained the treaty as a covenant between Māori and Queen Victoria, the head of state and Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

. With nearly half the Māori population following Christianity many looked at the treaty as a Biblical covenant – a sacred bond.

Afterwards, the chiefs then moved to a river flat below Busby's house and lawn and continued deliberations late into the night. Busby's house would later become known as the Treaty House

The Treaty House ( mi, Whare Tiriti) at Waitangi in Northland, New Zealand, is the former house of the British Resident in New Zealand, James Busby. The Treaty of Waitangi, the document that established the British Colony of New Zealand, was ...

and is today New Zealand's most visited historic building.

Hobson had planned for the signing to occur on 7 February however on the morning of 6 February 45 chiefs were waiting ready to sign. Around noon a ship carrying two officers from ''HMS Herald'' arrived and were surprised to hear they were waiting for the Governor so a boat was quickly despatched back to let him know. Although the official painting of the signing shows Hobson wearing full naval regalia, he was in fact not expecting the chiefs that day and was wearing his dressing gown or "in plain clothes, except his hat". Several hundred Māori were waiting and only Busby, Williams, Colenso and a few other Europeans.

Article Four

FrenchCatholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

Bishop Jean-Baptiste Pompallier soon joined the gathering and after Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

English priest and CMS mission head Rev Henry Williams read the Māori translation aloud from a final parchment version. Pompallier spoke to Hobson who then addressed Williams:

Williams attempted to do so vocally, but as this was technically another clause in the treaty, Colenso asked for it to be added in writing, which Williams did, also adding Māori custom. The statement says:

This addition is sometimes referred to as Article Four of the Treaty, and is recognised as relating to the right to freedom of religion and belief ().

First signings

The treaty signing began in the afternoon. Hobson headed the British signatories. Hōne Heke was the first of the Māori chiefs who signed that day. As each chief signed Hobson said "''He iwi tahi tātou''", meaning "We are owone people". This was probably at the request of Williams, knowing the significance, especially to Christian chiefs, 'Māori and British would be linked, as subjects of the Queen and followers of Christ'. Two chiefs, Marupō and Ruhe, protested strongly against the treaty as the signing took place but they eventually signed and after Marupō shook the Governor's hand, seized hold of his hat which was on the table and gestured to put it on. Over 40 chiefs signed the treaty that afternoon, which concluded with a chief leading three thundering cheers, and Colenso distributing gifts of two blankets and tobacco to each signatory.Later signings

Hobson considered the signing at Waitangi to be highly significant, he noted that twenty-six of the forty-six "head chiefs" had signed. Hobson had no intention of requiring the unanimous assent of Māori to the treaty, but was willing to accept a majority, as he reported that the signings at Waitangi represented "Clear recognition of the sovereign rights of Her Majesty over the northern parts of this island". Those that signed at Waitangi did not even represent the north as a whole; an analysis of the signatures shows that most were from the Bay of Islands only and that not many of the chiefs of the highest rank had signed on that day. Hobson considered the initial signing at Waitangi to be the "de facto" treaty, while later signings merely "ratified and confirmed it". To enhance the treaty's authority, eight additional copies were sent around the country to gather additional signatures: * theManukau

Manukau (), or Manukau Central, is a suburb of South Auckland, New Zealand, centred on the Manukau City Centre business district. It is located 23 kilometres south of the Auckland Central Business District, west of the Southern Motorway, so ...

-Kawhia

Kawhia Harbour (Maori: ''Kāwhia'') is one of three large natural inlets in the Tasman Sea coast of the Waikato region of New Zealand's North Island. It is located to the south of Raglan Harbour, Ruapuke and Aotea Harbour, 40 kilometres southw ...

copy (13 signatures),

* the Waikato

Waikato () is a local government region of the upper North Island of New Zealand. It covers the Waikato District, Waipa District, Matamata-Piako District, South Waikato District and Hamilton City, as well as Hauraki, Coromandel Peninsul ...

-Manukau copy (39 signatures),

* the Tauranga

Tauranga () is a coastal city in the Bay of Plenty region and the fifth most populous city of New Zealand, with an urban population of , or roughly 3% of the national population. It was settled by Māori late in the 13th century, colonised by ...

copy (21 signatures),

* the Bay of Plenty

The Bay of Plenty ( mi, Te Moana-a-Toi) is a region of New Zealand, situated around a bight of the same name in the northern coast of the North Island. The bight stretches 260 km from the Coromandel Peninsula in the west to Cape Runaw ...

copy (26 signatures),

* the Herald

A herald, or a herald of arms, is an officer of arms, ranking between pursuivant and king of arms. The title is commonly applied more broadly to all officers of arms.

Heralds were originally messengers sent by monarchs or noblemen to ...

- Bunbury copy (27 signatures),

* the Henry Williams copy (132 signatures),

* the Tūranga (East Coast) copy (41 signatures), and

* the Printed copy (5 signatures).

The Waitangi original received 240 signatures.

About 50 meetings were held from February to September 1840 to discuss and sign the copies, and a further 500 signatures were added to the treaty. While most did eventually sign, especially in the far north where most Māori lived, a number of chiefs and some tribal groups ultimately refused, including Pōtatau Te Wherowhero (Waikato iwi), Tuhoe, Te Arawa

Te Arawa is a confederation of Māori iwi and hapu (tribes and sub-tribes) of New Zealand who trace their ancestry to the Arawa migration canoe (''waka'').Ngāti Tuwharetoa

Iwi () are the largest social units in New Zealand Māori society. In Māori roughly means "people" or "nation", and is often translated as "tribe", or "a confederation of tribes". The word is both singular and plural in the Māori language, a ...

and possibly Moka 'Kainga-mataa'

Moka Kainga-mataa e Kaingamataa/Te Kaingamata/Te Kainga-mata/Te Kainga-mataa'' (1790s–1860s) was a Māori rangatira (chief) of the Ngā Puhi iwi from Northland in New Zealand. He was distinguished in war and an intelligent participant in the ...

. A number of non-signatory Waikato and Central North Island chiefs would later form a kind of confederacy with an elected monarch called the Kīngitanga. (The Kīngitanga Movement would later form a primary anti-government force in the New Zealand Wars

The New Zealand Wars took place from 1845 to 1872 between the New Zealand colonial government and allied Māori on one side and Māori and Māori-allied settlers on the other. They were previously commonly referred to as the Land Wars or the M ...

.) While copies were moved around the country to give as many tribal leaders as possible the opportunity to sign, some missed out, especially in the South Island, where inclement weather prevented copies from reaching Otago

Otago (, ; mi, Ōtākou ) is a region of New Zealand located in the southern half of the South Island administered by the Otago Regional Council. It has an area of approximately , making it the country's second largest local government reg ...

or Stewart Island

Stewart Island ( mi, Rakiura, 'Aurora, glowing skies', officially Stewart Island / Rakiura) is New Zealand's third-largest island, located south of the South Island, across the Foveaux Strait. It is a roughly triangular island with a total ...

. Assent to the treaty was large in Kaitaia

Kaitaia ( mi, Kaitāia) is a town in the Far North District of New Zealand, at the base of the Aupouri Peninsula, about 160 km northwest of Whangārei. It is the last major settlement on State Highway 1. Ahipara Bay, the southern end of ...

, as well as the Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by ...

to Whanganui

Whanganui (; ), also spelled Wanganui, is a city in the Manawatū-Whanganui region of New Zealand. The city is located on the west coast of the North Island at the mouth of the Whanganui River, New Zealand's longest navigable waterway. Whang ...

region, but there were at least some holdouts in every other part of New Zealand.

Māori were the first indigenous race to sign a document giving them British citizenship and promising their protection. Hobson was grateful to Williams and stated a British colony would not have been established in New Zealand without the CMS missionaries.

Sovereignty proclamations

On 21 May 1840, Lieutenant-Governor Hobson proclaimed sovereignty over the whole country, (the North Island by Treaty and the South Island and Stewart Island by discovery) and New Zealand was constituted theColony of New Zealand

The Colony of New Zealand was a Crown colony of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland that encompassed the islands of New Zealand from 1841 to 1907. The power of the British government was vested in the Governor of New Zealand, as th ...

, separate from New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

by a Royal Charter issued on 16 November 1840, with effect from 3 May 1841.

In Hobson's first dispatch to the British government, he stated that the North Island had been ceded with "unanimous adherence" (which was not accurate) and while Hobson claimed the South Island by discovery based on the "uncivilised state of the natives", in actuality he had no basis to make such a claim. Hobson issued the proclamation because he felt it was forced on him by settlers from the New Zealand Company at Port Nicholson who had formed an independent settlement government and claimed legality from local chiefs, two days after the proclamation on 23 May 1840, Hobson declared the settlement's government as illegal. Hobson also failed to report to the British government that the Māori text of the treaty was substantially different from the English one (which he might not have known at the time) and also reported that both texts had received 512 signatures, where in truth the majority of signatures had been on the Māori copies that had been sent around the country, rather than on the single English copy. Basing their decision on this information, on 2 October 1840, the Colonial Office approved Hobson's proclamation. They did not have second thoughts when later reports revealed more detail about the inadequacies of the treaty negotiations, and they did not take issue with the fact that large areas of the North Island had not signed. The government had never asked for Hobson to obtain unanimous agreement from the indigenous people.

Extant copies

In 1841, Treaty documents, housed in an iron box, narrowly escaped damage when the government offices at Official Bay inAuckland

Auckland (pronounced ) ( mi, Tāmaki Makaurau) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. The most populous urban area in the country and the fifth largest city in Oceania, Auckland has an urban population of about I ...

were destroyed by fire. They disappeared from sight until 1865 when a Native Department officer worked on them in Wellington at the request of parliament and produced an erroneous list of signatories. The papers were fastened together and then deposited in a safe in the Colonial Secretary's office.

In 1877, the English-language rough draft of the treaty was published along with photolithographic facsimiles

A facsimile (from Latin ''fac simile'', "to make alike") is a copy or reproduction of an old book, manuscript, map, art print, or other item of historical value that is as true to the original source as possible. It differs from other forms of ...

, and the originals were returned to storage. In 1908, historian and bibliographer Thomas Hocken

Thomas Morland Hocken (14 January 1836 – 17 May 1910) was a New Zealand collector, bibliographer and researcher.

Early life

He was born in Rutlandshire on 14 January 1836, the son of Wesleyan minister Joshua Hocken, and educated at Woodho ...

, searching for historical documents, found the treaty papers in the basement of the Old Government Buildings in poor condition, damaged at the edges by water and partly eaten by rodents. The papers were restored by the Dominion Museum

The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa is New Zealand's national museum and is located in Wellington. ''Te Papa Tongarewa'' translates literally to "container of treasures" or in full "container of treasured things and people that spring fr ...

in 1913 and kept in special boxes from then on. In February 1940, the treaty documents were taken to Waitangi for display in the Treaty House

The Treaty House ( mi, Whare Tiriti) at Waitangi in Northland, New Zealand, is the former house of the British Resident in New Zealand, James Busby. The Treaty of Waitangi, the document that established the British Colony of New Zealand, was ...

during the Centenary

{{other uses, Centennial (disambiguation), Centenary (disambiguation)

A centennial, or centenary in British English, is a 100th anniversary or otherwise relates to a century, a period of 100 years.

Notable events

Notable centennial events at a ...

celebrations. It was possibly the first time the treaty document had been on public display since it was signed. After the outbreak of war with Japan, they were placed with other state documents in an outsize luggage trunk and deposited for secure custody with the Public Trustee

The public trustee is an office established pursuant to national (and, if applicable, state or territory) statute, to act as a trustee, usually when a sum is required to be deposited as security by legislation, if courts remove another trustee, o ...

at Palmerston North

Palmerston North (; mi, Te Papa-i-Oea, known colloquially as Palmy) is a city in the North Island of New Zealand and the seat of the Manawatū-Whanganui region. Located in the eastern Manawatu Plains, the city is near the north bank of the ...

by the local member of parliament, who did not tell staff what was in the case. However, as the case was too large to fit in the safe, the treaty documents spent the war at the side of a back corridor in the Public Trust office.

In 1956, the Department of Internal Affairs

The Department of Internal Affairs (DIA), or in te reo Māori, is the public service department of New Zealand charged with issuing passports; administering applications for citizenship and lottery grants; enforcing censorship and gambling la ...

placed the treaty documents in the care of the Alexander Turnbull Library

The National Library of New Zealand ( mi, Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa) is New Zealand's legal deposit library charged with the obligation to "enrich the cultural and economic life of New Zealand and its interchanges with other nations" (''Nat ...

and they were displayed in 1961. Further preservation steps were taken in 1966, with improvements to the display conditions. From 1977 to 1980, the library extensively restored the documents before the treaty was deposited in the Reserve Bank.

In anticipation of a decision to exhibit the document in 1990 (the sesquicentennial of the signing), full documentation and reproduction photography was carried out. Several years of planning culminated with the opening of the climate-controlled Constitution Room at the National Archives by Mike Moore, Prime Minister of New Zealand

The prime minister of New Zealand ( mi, Te pirimia o Aotearoa) is the head of government of New Zealand. The prime minister, Jacinda Ardern, leader of the New Zealand Labour Party, took office on 26 October 2017.

The prime minister (inf ...

, in November 1990. It was announced in 2012 that the nine Treaty of Waitangi sheets would be relocated to the National Library of New Zealand

The National Library of New Zealand ( mi, Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa) is New Zealand's legal deposit library charged with the obligation to "enrich the cultural and economic life of New Zealand and its interchanges with other nations" (''Na ...

in 2013. In 2017, the He Tohu permanent exhibition at the National Library opened, displaying the treaty documents along with the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of th ...

and the 1893 Women's Suffrage Petition

The 1893 women's suffrage petition was the third of three petitions to the New Zealand Government in support of women's suffrage and resulted in the Electoral Act 1893, which gave women the right to vote in the 1893 general election. The 1893 ...

.

Treaty text, meaning and interpretation

English text

The treaty itself is short, consisting of a preamble and three articles. The English text (from which the Māori text is translated) starts with the preamble and presents Queen Victoria "being desirous to establish a settled form of Civil Government", and invites Māori chiefs to concur in the following articles. The first article of the English text grants theQueen of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiwi ...

"absolutely and without reservation all the rights and powers of Sovereignty" over New Zealand. The second article guarantees to the chiefs full "exclusive and undisturbed possession of their Lands and Estates Forests Fisheries and other properties". It also specifies that Māori will sell land only to the Crown (Crown pre-emption). The third article guarantees to all Māori the same rights as all other British subjects.

Māori text

The Māori text has the same overall structure, with a preamble and three articles. The first article indicates that the Māori chiefs "give absolutely to the Queen of England for ever the complete government over their land" (according to a modern translation by Hugh Kāwharu). With no adequate word available to substitute for 'sovereignty', as it was not a concept in Māori society at the time, the translators instead used ''kāwanatanga'' (governorship or government). The second article guarantees all Māori "chieftainship over their lands, villages and all their treasures" (translated), with 'treasures' here translating from ''taonga'' to mean more than just physical possessions (as in the English text), but also other elements of cultural heritage. The second article also says: "Chiefs will sell land to the Queen at a price agreed to by the person owning it and by the person buying it (the latter being) appointed by the Queen as her purchase agent" (translated), which does not accurately convey the pre-emption clause of the English text. The third article gives Māori the "same rights and duties of citizenship as the people of England" (translated); roughly the same as the English text.Differences

The English and Māori texts differ. As some words in the English treaty did not translate directly into the writtenMāori language

Māori (), or ('the Māori language'), also known as ('the language'), is an Eastern Polynesian language spoken by the Māori people, the indigenous population of mainland New Zealand. Closely related to Cook Islands Māori, Tuamotuan, and ...

of the time, the Māori text is not a literal translation of the English text It has been claimed that Henry Williams, the missionary entrusted with translating the treaty from English, was fluent in Māori and that far from being a poor translator he had in fact carefully crafted both versions to make each palatable to both parties without either noticing inherent contradictions.

The differences between the two texts have made it difficult to interpret the treaty and continue to undermine its effect. The most critical difference between the texts revolves around the interpretation of three Māori words: '' kāwanatanga'' (governorship), which is ceded to the Queen in the first article; ''rangatiratanga

' is a Māori language term that translates literally to 'highest chieftainship' or 'unqualified chieftainship', but is also translated as "self-determination", "sovereignty" and "absolute sovereignty". The very translation of is important to ...

'' (chieftainship) not ''mana

According to Melanesian and Polynesian mythology, ''mana'' is a supernatural force that permeates the universe. Anyone or anything can have ''mana''. They believed it to be a cultivation or possession of energy and power, rather than being ...

'' (leadership) (which was stated in the Declaration of Independence just five years before the treaty was signed), which is retained by the chiefs in the second; and '' taonga'' (property or valued possessions), which the chiefs are guaranteed ownership and control of, also in the second article. Few Māori involved with the treaty negotiations understood the concepts of sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

or "governorship", as they were used by 19th-century Europeans, and lawyer Moana Jackson

Moana Jackson (10 October 1945 – 31 March 2022) was a New Zealand lawyer specialising in constitutional law, the Treaty of Waitangi and international indigenous issues. Jackson was of Ngāti Kahungunu and Ngāti Porou descent. He was an a ...

has stated that "ceding mana or sovereignty in a treaty was legally and culturally incomprehensible in Māori terms".

Furthermore, ''kāwanatanga'' is a loan translation from "governorship" and was not part of the Māori language. The term had been used by Henry Williams in his translation of the Declaration of the Independence of New Zealand which was signed by 35 northern Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the Co ...

chiefs at Waitangi on 28 October 1835. The Declaration of Independence of New Zealand had stated "''Ko te Kīngitanga ko te mana i te w nua''" to describe "all sovereign power and authority in the land". There is considerable debate about what would have been a more appropriate term. Some scholars, notably Ruth Ross, argue that ''mana'' (prestige, authority) would have more accurately conveyed the transfer of sovereignty. However, it has more recently been argued by others, including Judith Binney, that ''mana'' would not have been appropriate. This is because ''mana'' is not the same thing as sovereignty, and also because no-one can give up their ''mana''.

The English-language text recognises Māori rights to "properties", which seems to imply physical and perhaps intellectual property. The Māori text, on the other hand, mentions "taonga", meaning "treasures" or "precious things". In Māori usage the term applies much more broadly than the English concept of legal property, and since the 1980s courts have found that the term can encompass intangible things such as language and culture. Even where physical property such as land is concerned, differing cultural understandings as to what types of land are able to be privately owned have caused problems, as for example in the foreshore and seabed controversy of 2003–04.

The pre-emption clause is generally not well translated. While pre-emption was present in the treaty from the very first draft, it was translated to ''hokonga'', a word which simply meant "to buy, sell, or trade". Many Māori apparently believed that they were simply giving the British Queen first offer on land, after which they could sell it to anyone. Another, less important, difference is that ''Ingarani'', meaning England alone, is used throughout in the Māori text, whereas "the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was a sovereign state in the British Isles that existed between 1801 and 1922, when it included all of Ireland. It was established by the Acts of Union 1800, which merged the Kingdom of Grea ...

" is used in the first paragraph of the English.

Based on these differences, there are many academics who argue that the two versions of the treaty are distinctly different documents they refer to as "Te Tiriti o Waitangi" and "The Treaty of Waitangi", and that the Māori text should take precedence, because it was the one that was signed at Waitangi and by the most signatories. The Waitangi Tribunal, tasked with deciding issues raised by the differences between the two texts, also gives additional weight to the Māori text in its interpretations of the treaty.

The entire issue is further complicated by the fact that, at the time, writing was a novel introduction to Māori society. As members of a predominately oral society, Māori present at the signing of the treaty would have placed more value and reliance on what Hobson and the missionaries said, rather than the written words of the treaty document. Although there is still a great deal of scholarly debate surrounding the extent to which literacy had permeated Māori society at the time of the signing, what can be stated with clarity is that of the 600 plus chiefs who signed the written document only 12 signed their names in the Latin alphabet

The Latin alphabet or Roman alphabet is the collection of letters originally used by the ancient Romans to write the Latin language. Largely unaltered with the exception of extensions (such as diacritics), it used to write English and the ...

. Many others conveyed their identity by drawing parts of their ''moko

In the mythology of Mangaia in the Cook Islands, Moko is a wily character and grandfather of the heroic Ngaru.

Moko is a ruler or king of the lizard

Lizards are a widespread group of squamate reptiles, with over 7,000 species, ranging acro ...

'' (personal facial tattoo), while still others marked the document with an X.

Māori beliefs and attitudes towards ownership and use of land were different from those prevailing in Britain and Europe. The chiefs would traditionally grant permission for the land to be used for a time for a particular purpose. A northern chief, Nōpera Panakareao

Nōpera Panakareao (? – 13 April 1856) was a New Zealand tribal leader, evangelist and assessor. Of Māori descent, he identified with the Te Rarawa iwi.

Nōpera lived at Kaitaia. He became a friend of William Gilbert Puckey, the son of William ...

, also early on summarised his understanding of the treaty as "''Ko te atarau o te whenua i riro i a te kuini, ko te tinana o te whenua i waiho ki ngā Māori''" (The shadow of the land will go to the Queen f England but the substance of the land will remain with us). Nopera later reversed his earlier statement – feeling that the substance of the land had indeed gone to the Queen; only the shadow remained for the Māori.

Role in New Zealand society

Effects on Māori land and rights (1840–1960)

Colony of New Zealand

In November 1840 aroyal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, b ...

was signed by Queen Victoria, establishing New Zealand as a Crown colony

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony administered by The Crown within the British Empire. There was usually a Governor, appointed by the British monarch on the advice of the UK Government, with or without the assistance of a local Council ...

separate from New South Wales from 3 May 1841. In 1846 the Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprem ...

passed the New Zealand Constitution Act 1846

The New Zealand Constitution Act 1846 (9 & 10 Vict. c. 103) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom intended to grant self-government to the Colony of New Zealand, but it was never fully implemented. The Act's long title was ''An Act t ...

which granted self-government to the colony, requiring Māori to pass an English-language test to be able to participate in the new colonial government. In the same year, Lord Stanley

Earl of Derby ( ) is a title in the Peerage of England. The title was first adopted by Robert de Ferrers, 1st Earl of Derby, under a creation of 1139. It continued with the Ferrers family until the 6th Earl forfeited his property toward the en ...

, the British Colonial Secretary, who was a devout Anglican, three times British Prime Minister and oversaw the passage of the Slavery Abolition Act 1833

The Slavery Abolition Act 1833 (3 & 4 Will. IV c. 73) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which provided for the gradual abolition of slavery in most parts of the British Empire. It was passed by Earl Grey's reforming administrat ...

, was asked by Governor George Grey

Sir George Grey, KCB (14 April 1812 – 19 September 1898) was a British soldier, explorer, colonial administrator and writer. He served in a succession of governing positions: Governor of South Australia, twice Governor of New Zealand, ...

how far he was expected to abide by the treaty. The direct response in the Queen's name was:

At Governor Grey's request, this Act was suspended in 1848, as Grey argued it would place the majority Māori under the control of the minority British settlers. Instead, Grey drafted what would later become the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852

The New Zealand Constitution Act 1852 (15 & 16 Vict. c. 72) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that granted self-government to the Colony of New Zealand. It was the second such Act, the previous 1846 Act not having been fully ...

, which determined the right to vote based on land-ownership franchise. Since most Māori land was communally owned, very few Māori had the right to vote for the institutions of the colonial government. The 1852 Constitution Act also included provision for "Māori districts", where Māori law and custom were to be preserved, but this section was never implemented by the Crown.

Following the election of the first parliament in 1853, responsible government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive br ...

was instituted in 1856. The direction of "native affairs" was kept at the sole discretion of the Governor, meaning control of Māori affairs and land remained outside of the elected ministry. This quickly became a point of contention between the Governor and the colonial parliament, who retained their own "Native Secretary" to advise them on "native affairs". In 1861, Governor Grey agreed to consult the ministers in relation to native affairs, but this position only lasted until his recall from office in 1867. Grey's successor as Governor, George Bowen

Sir George Ferguson Bowen (; 2 November 1821 – 21 February 1899), was an Irish author and colonial administrator whose appointments included postings to the Ionian Islands, Queensland, New Zealand, Victoria, Mauritius and Hong Kong.R. B. ...

, took direct control of native affairs until his term ended in 1870. From then on, the elected ministry, led by the Premier

Premier is a title for the head of government in central governments, state governments and local governments of some countries. A second in command to a premier is designated as a deputy premier.

A premier will normally be a head of governm ...

, controlled the colonial government's policy on Māori land.

Right of pre-emption

The short-term effect of the treaty was to prevent the sale of Māori land to anyone other than the Crown. This was intended to protect Māori from the kinds of shady land purchases which had alienatedindigenous people

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...