Treaty of Mesilla on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Gadsden Purchase ( es, region=MX, la Venta de La Mesilla "The Sale of La Mesilla") is a region of present-day southern

As the railroad age evolved, business-oriented Southerners saw that a railroad linking the South with the Pacific Coast would expand trade opportunities. They thought the topography of the southern portion of the original boundary line was too mountainous to allow a direct route. Projected southern railroad routes tended to veer to the north as they proceeded eastward, which would favor connections with northern railroads and ultimately favor northern seaports. Southerners saw that to avoid the mountains, a route with a southeastern terminus might need to swing south into what was still Mexican territory.

The administration of President Pierce, strongly influenced by Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, saw an opportunity to acquire land for the railroad, as well as to acquire significant other territory from northern Mexico. In those years, the debate over slavery in the United States entered into many other debates, as the acquisition of new territory opened the question of whether it would be slave or free territory; in this case, the debate over slavery ended progress on construction of a southern transcontinental rail line until the early 1880s, although the preferred land became part of the nation and was used as intended after the Civil War.

As the railroad age evolved, business-oriented Southerners saw that a railroad linking the South with the Pacific Coast would expand trade opportunities. They thought the topography of the southern portion of the original boundary line was too mountainous to allow a direct route. Projected southern railroad routes tended to veer to the north as they proceeded eastward, which would favor connections with northern railroads and ultimately favor northern seaports. Southerners saw that to avoid the mountains, a route with a southeastern terminus might need to swing south into what was still Mexican territory.

The administration of President Pierce, strongly influenced by Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, saw an opportunity to acquire land for the railroad, as well as to acquire significant other territory from northern Mexico. In those years, the debate over slavery in the United States entered into many other debates, as the acquisition of new territory opened the question of whether it would be slave or free territory; in this case, the debate over slavery ended progress on construction of a southern transcontinental rail line until the early 1880s, although the preferred land became part of the nation and was used as intended after the Civil War.

In January 1845,

In January 1845,

The

The

Article XI of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo contained a guarantee that the United States would protect Mexicans by preventing cross-border raids by local Comanche and Apache tribes. At the time the treaty was ratified, Secretary of State James Buchanan had believed that the United States had both the commitment and resources to enforce this promise.. Historian

Article XI of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo contained a guarantee that the United States would protect Mexicans by preventing cross-border raids by local Comanche and Apache tribes. At the time the treaty was ratified, Secretary of State James Buchanan had believed that the United States had both the commitment and resources to enforce this promise.. Historian

The Memphis commercial convention of 1849 recommended that the United States pursue the trans-isthmus route, since it appeared unlikely that a transcontinental railroad would be built anytime soon. Interests in Louisiana were especially adamant about this option, as they believed that any transcontinental railroad would divert commercial traffic away from the Mississippi and New Orleans, and they at least wanted to secure a southern route. Also showing interest was Peter A. Hargous of New York who ran an import-export business between New York and Vera Cruz. Hargous purchased the rights to the route for $25,000 (equivalent to $ in ), but realized that the grant had little value unless it was supported by the Mexican and American governments.

In Mexico, topographical officer George W. Hughes reported to Secretary of State John M. Clayton that a railroad across the isthmus was a "feasible and practical" idea. Clayton then instructed

The Memphis commercial convention of 1849 recommended that the United States pursue the trans-isthmus route, since it appeared unlikely that a transcontinental railroad would be built anytime soon. Interests in Louisiana were especially adamant about this option, as they believed that any transcontinental railroad would divert commercial traffic away from the Mississippi and New Orleans, and they at least wanted to secure a southern route. Also showing interest was Peter A. Hargous of New York who ran an import-export business between New York and Vera Cruz. Hargous purchased the rights to the route for $25,000 (equivalent to $ in ), but realized that the grant had little value unless it was supported by the Mexican and American governments.

In Mexico, topographical officer George W. Hughes reported to Secretary of State John M. Clayton that a railroad across the isthmus was a "feasible and practical" idea. Clayton then instructed

A treaty initiated in the Fillmore administration that would provide joint Mexican and United States protection for the Sloo grant was signed in Mexico on on March 21, 1853. At the same time that this treaty was received in Washington, Pierce learned that New Mexico Territorial Governor William C. Lane had issued a proclamation claiming the Mesilla Valley as part of New Mexico, leading to protests from Mexico. Pierce was also aware of efforts by France, through its consul in San Francisco, to acquire the Mexican state of Sonora.

Pierce recalled Lane in May and replaced him with David Meriwether of Kentucky. Meriwether was given orders to stay out of the Mesilla Valley until negotiations with Mexico could be completed. With the encouragement of Davis, Pierce also appointed James Gadsden as ambassador to Mexico, with specific instructions to negotiate with Mexico over the acquisition of additional territory. Secretary of State William L. Marcy gave Gadsden clear instructions: he was to secure the Mesilla Valley for the purposes of building a railroad through it, convince Mexico that the US had done its best regarding the Indian raids, and elicit Mexican cooperation in efforts by US citizens to build a canal or railroad across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Supporting the Sloo interests was not part of the instructions. Gadsden met with Santa Anna in Mexico City on September 25, 1853, to discuss the terms of the treaty.

The Mexican government was going through political and financial turmoil. In the process, Santa Anna had been returned to power about the same time that Pierce was inaugurated. Santa Anna was willing to deal with the United States because he needed money to rebuild the

A treaty initiated in the Fillmore administration that would provide joint Mexican and United States protection for the Sloo grant was signed in Mexico on on March 21, 1853. At the same time that this treaty was received in Washington, Pierce learned that New Mexico Territorial Governor William C. Lane had issued a proclamation claiming the Mesilla Valley as part of New Mexico, leading to protests from Mexico. Pierce was also aware of efforts by France, through its consul in San Francisco, to acquire the Mexican state of Sonora.

Pierce recalled Lane in May and replaced him with David Meriwether of Kentucky. Meriwether was given orders to stay out of the Mesilla Valley until negotiations with Mexico could be completed. With the encouragement of Davis, Pierce also appointed James Gadsden as ambassador to Mexico, with specific instructions to negotiate with Mexico over the acquisition of additional territory. Secretary of State William L. Marcy gave Gadsden clear instructions: he was to secure the Mesilla Valley for the purposes of building a railroad through it, convince Mexico that the US had done its best regarding the Indian raids, and elicit Mexican cooperation in efforts by US citizens to build a canal or railroad across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Supporting the Sloo interests was not part of the instructions. Gadsden met with Santa Anna in Mexico City on September 25, 1853, to discuss the terms of the treaty.

The Mexican government was going through political and financial turmoil. In the process, Santa Anna had been returned to power about the same time that Pierce was inaugurated. Santa Anna was willing to deal with the United States because he needed money to rebuild the

Pierce and his cabinet began debating the treaty in January 1854. Although disappointed in the amount of territory secured and some of the terms, Pierce signed it, and submitted it to the Senate on February 10. Gadsden, however, suggested that northern Senators would block the treaty to deny the South a railroad.

The treaty needed a two-thirds vote in favor of ratification in the US Senate, where it met strong opposition. Anti-slavery senators opposed further acquisition of slave territory. Lobbying by speculators gave the treaty a bad reputation. Some Senators objected to furnishing Santa Anna financial assistance.

The treaty reached the Senate as that body focused on the debate over the

Pierce and his cabinet began debating the treaty in January 1854. Although disappointed in the amount of territory secured and some of the terms, Pierce signed it, and submitted it to the Senate on February 10. Gadsden, however, suggested that northern Senators would block the treaty to deny the South a railroad.

The treaty needed a two-thirds vote in favor of ratification in the US Senate, where it met strong opposition. Anti-slavery senators opposed further acquisition of slave territory. Lobbying by speculators gave the treaty a bad reputation. Some Senators objected to furnishing Santa Anna financial assistance.

The treaty reached the Senate as that body focused on the debate over the

In 1846, James Gadsden, then president of the

In 1846, James Gadsden, then president of the

Ghostarchive

and th

Wayback Machine

A supporting character in the 2021 novel '' Billy Summers'' by Stephen King is named "Gadsden Drake" after the Gadsden Purchase.

US Geological Survey

USGS Public Lands Survey Map including survey township (6 mile) lines. * ''Map of proposed Arizona Territory. From explorations by A. B. Gray & others, to accompany memoir by Lieut. Mowry U.S. Army, Delegate elect.'' with some proposed railroad route

Medium-sized JPGZoom navigator

National Park Service

Map including route of the

Gadsden Purchase, 1853–1854

Office of the Historian, US Department of State

3-cent commemorative stamp

showing small version of northeast boundary of Purchasei.e. claiming more territory for US pre-Purchase. *

Map of North America at the time of the Gadsden Purchase at omniatlas.com

{{coord, 32.1318, -110.5535, display=title, region:US-AZ_type:adm2nd 1853 treaties History of the Southwestern United States History of the American West 1853 in Mexico 1853 in the United States History of United States expansionism Independent Mexico Mexico–United States border New Mexico Territory Pre-statehood history of Arizona Treaties involving territorial changes Presidency of Franklin Pierce Purchased territories

Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

and southwestern New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ke ...

that the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

acquired from Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

by the Treaty of Mesilla, which took effect on June 8, 1854. The purchase included lands south of the Gila River and west of the Rio Grande where the U.S. wanted to build a transcontinental railroad

A transcontinental railroad or transcontinental railway is contiguous railroad trackage, that crosses a continental land mass and has terminals at different oceans or continental borders. Such networks can be via the tracks of either a single ...

along a deep southern route, which the Southern Pacific Railroad later completed in 1881–1883. The purchase also aimed to resolve other border issues.

The first draft was signed on December 30, 1853, by James Gadsden

James Gadsden (May 15, 1788December 26, 1858) was an American diplomat, soldier and businessman after whom the Gadsden Purchase is named, pertaining to land which the United States bought from Mexico, and which became the southern portions of Ar ...

, U.S. ambassador to Mexico, and by Antonio López de Santa Anna

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón (; 21 February 1794 – 21 June 1876),Callcott, Wilfred H., "Santa Anna, Antonio Lopez De,''Handbook of Texas Online'' Retrieved 18 April 2017. usually known as Santa Ann ...

, president of Mexico. The U.S. Senate voted in favor of ratifying it with amendments on April 25, 1854, and then sent it to President Franklin Pierce. Mexico's government and its General Congress or Congress of the Union took final approval action on June 8, 1854, when the treaty took effect. The purchase was the last substantial territorial acquisition in the contiguous United States, and defined the Mexico–United States border

The Mexico–United States border ( es, frontera Estados Unidos–México) is an international border separating Mexico and the United States, extending from the Pacific Ocean in the west to the Gulf of Mexico in the east. The border trave ...

. The Arizona cities of Tucson

, "(at the) base of the black ill

, nicknames = "The Old Pueblo", "Optics Valley", "America's biggest small town"

, image_map =

, mapsize = 260px

, map_caption = Interactive map ...

and Yuma are on territory acquired by the U.S. in the Gadsden Purchase.

The financially strapped government of Santa Anna agreed to the sale, which netted Mexico $10 million

(equivalent to $ in ). After the devastating loss of Mexican territory to the U.S. in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

(1846–48) and the continued unauthorized military expeditions in the zone led by New Mexico territorial governor and noted filibuster William Carr Lane, some historians argue that Santa Anna may have calculated it was better to yield territory by treaty and receive payment rather than have the territory simply seized by the U.S.

Desire for a southern transcontinental rail line

As the railroad age evolved, business-oriented Southerners saw that a railroad linking the South with the Pacific Coast would expand trade opportunities. They thought the topography of the southern portion of the original boundary line was too mountainous to allow a direct route. Projected southern railroad routes tended to veer to the north as they proceeded eastward, which would favor connections with northern railroads and ultimately favor northern seaports. Southerners saw that to avoid the mountains, a route with a southeastern terminus might need to swing south into what was still Mexican territory.

The administration of President Pierce, strongly influenced by Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, saw an opportunity to acquire land for the railroad, as well as to acquire significant other territory from northern Mexico. In those years, the debate over slavery in the United States entered into many other debates, as the acquisition of new territory opened the question of whether it would be slave or free territory; in this case, the debate over slavery ended progress on construction of a southern transcontinental rail line until the early 1880s, although the preferred land became part of the nation and was used as intended after the Civil War.

As the railroad age evolved, business-oriented Southerners saw that a railroad linking the South with the Pacific Coast would expand trade opportunities. They thought the topography of the southern portion of the original boundary line was too mountainous to allow a direct route. Projected southern railroad routes tended to veer to the north as they proceeded eastward, which would favor connections with northern railroads and ultimately favor northern seaports. Southerners saw that to avoid the mountains, a route with a southeastern terminus might need to swing south into what was still Mexican territory.

The administration of President Pierce, strongly influenced by Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, saw an opportunity to acquire land for the railroad, as well as to acquire significant other territory from northern Mexico. In those years, the debate over slavery in the United States entered into many other debates, as the acquisition of new territory opened the question of whether it would be slave or free territory; in this case, the debate over slavery ended progress on construction of a southern transcontinental rail line until the early 1880s, although the preferred land became part of the nation and was used as intended after the Civil War.

Southern route for the Transcontinental Railroad

Southern commercial conventions

In January 1845,

In January 1845, Asa Whitney

Asa Whitney (1797–1872) was a highly successful dry-goods merchant and transcontinental railroad promoter.

He was one of the first backers of an American transcontinental railway. A trip to China in 1842–44 impressed upon Whitney the need ...

of New York presented the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

with the first plan to construct a transcontinental railroad. Although Congress took no action on his proposal, a commercial convention of 1845 in Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

took up the issue. Prominent attendees included John C. Calhoun, Clement C. Clay, Sr., John Bell, William Gwin, and Edmund P. Gaines

Edmund Pendleton Gaines (March 20, 1777 – June 6, 1849) was a career United States Army officer who served for nearly fifty years, and attained the rank of major general by brevet. He was one of the Army's senior commanders during its format ...

, but James Gadsden

James Gadsden (May 15, 1788December 26, 1858) was an American diplomat, soldier and businessman after whom the Gadsden Purchase is named, pertaining to land which the United States bought from Mexico, and which became the southern portions of Ar ...

of South Carolina was influential in the convention's recommending a southern route for the proposed railroad. The route was to begin in Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

and end in San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United State ...

or Mazatlán

Mazatlán () is a city in the Mexican state of Sinaloa. The city serves as the municipal seat for the surrounding '' municipio'', known as the Mazatlán Municipality. It is located at on the Pacific coast, across from the southernmost tip ...

. Southerners hoped that such a route would ensure Southern prosperity, while opening the "West to southern influence and settlement".

Southern interest in railroads in general, and the Pacific railroad in particular, accelerated after the conclusion of the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

in 1848. During that war, topographical

Topography is the study of the forms and features of land surfaces. The topography of an area may refer to the land forms and features themselves, or a description or depiction in maps.

Topography is a field of geoscience and planetary sc ...

officers William H. Emory

William Hemsley Emory (September 7, 1811 – December 1, 1887) was a prominent American surveyor and civil engineer in the 19th century. As an officer in the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers he specialized in mapping the United State ...

and James W. Abert had conducted surveys that demonstrated the feasibility of a railroad's originating in El Paso

El Paso (; "the pass") is a city in and the seat of El Paso County in the western corner of the U.S. state of Texas. The 2020 population of the city from the U.S. Census Bureau was 678,815, making it the 23rd-largest city in the U.S., the s ...

or western Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the O ...

and ending in San Diego. J. D. B. DeBow, the editor of ''DeBow's Review

''DeBow's Review'' was a widely-circulated magazine

"DEBOW'S REVIEW" (publication titles/dates/locations/notes),

APS II, Reels 382 & 383, webpage

of "agricultural, commercial, and industrial progress and resource" in the American South during ...

'', and Gadsden both publicized within the South the benefits of building this railroad.

Gadsden had become the president of the South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company

The South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company was a railroad in South Carolina that operated independently from 1830 to 1844. One of the first railroads in North America to be chartered and constructed, it provided the first steam-powered, schedu ...

in 1839; about a decade later, the company had laid of track extending west from Charleston, South Carolina, and was $3 million (equivalent to $ in ) in debt. Gadsden wanted to connect all Southern railroads into one sectional network.. He was concerned that the increasing railroad construction in the North was shifting trade in lumber, farm and manufacturing goods from the traditional north–south route based on the Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

and Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

rivers to an east–west axis that would bypass the South. He also saw Charleston, his home town, losing its prominence as a seaport. In addition, many Southern business interests feared that a northern transcontinental route would exclude the South from trade with the Orient. Other Southerners argued for diversification from a plantation economy to keep the South independent of northern bankers.

In October 1849, the southern interests held a convention to discuss railroads in Memphis, in response to a convention in St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

earlier that fall which discussed a northern route. The Memphis convention overwhelmingly advocated the construction of a route beginning there, to connect with an El Paso, Texas to San Diego, California line. Disagreement arose only over the issue of financing. The convention president, Matthew Fontaine Maury

Matthew Fontaine Maury (January 14, 1806February 1, 1873) was an American oceanographer and naval officer, serving the United States and then joining the Confederacy during the American Civil War.

He was nicknamed "Pathfinder of the Seas" and i ...

of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, preferred strict private financing, whereas John Bell and others thought that federal land grants to railroad developers would be necessary.

James Gadsden and California

Gadsden supportednullification

Nullification may refer to:

* Nullification (U.S. Constitution), a legal theory that a state has the right to nullify any federal law deemed unconstitutional with respect to the United States Constitution

* Nullification Crisis, the 1832 confront ...

in 1831. When California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

was admitted to the Union as a free state in 1850, he advocated secession by South Carolina. Gadsden considered slavery "a social blessing" and abolitionists "the greatest curse of the nation".

When the secession proposal failed, Gadsden worked with his cousin Isaac Edward Holmes, a lawyer in San Francisco since 1851, and California state senator Thomas Jefferson Green

Thomas Jefferson Green (February 14, 1802 – December 12, 1863) was an American politician who served in the legislatures of three different U.S. states and also of Texas, which was not yet a state.

Biography

Born in Warren County, North Carol ...

, in an attempt to divide California into northern and southern portions and proposed that the southern part allow slavery. Gadsden planned to establish a slave-holding colony there based on rice, cotton, and sugar, and wanted to use slave labor to build a railroad and highway that originated in either San Antonio

("Cradle of Freedom")

, image_map =

, mapsize = 220px

, map_caption = Interactive map of San Antonio

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = United States

, subdivision_type1= State

, subdivision_name1 = Texas

, subdivision_t ...

or the Red River valley. The railway or highway would transport people to the California gold fields. Toward this end, on December 31, 1851, Gadsden asked Green to secure from the California state legislature a large land grant located between the 34th and 36th parallels, along the proposed dividing line for the two California states.

A few months later, Gadsden and 1,200 potential settlers from South Carolina and Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

submitted a petition to the California legislature

The California State Legislature is a bicameral state legislature consisting of a lower house, the California State Assembly, with 80 members; and an upper house, the California State Senate, with 40 members. Both houses of the Legislatu ...

for permanent citizenship and permission to establish a rural district that would be farmed by "not less than Two Thousand of their African Domestics". The petition stimulated some debate, but it finally died in committee.

Stephen Douglas and land grants

TheCompromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican–Am ...

, which created the Utah Territory

The Territory of Utah was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Utah, the 45th state ...

and the New Mexico Territory, would facilitate a southern route to the West Coast since all territory for the railroad was now organized and would allow for federal land grants as a financing measure. Competing northern or central routes championed, respectively, by U.S. Senators

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

Stephen Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party for president in the 1860 presidential election, which wa ...

of Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rockf ...

and Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

, would still need to go through unorganized territories. Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853; he was the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former member of the U.S. House of Represen ...

established a precedent for using federal land grants when he signed a bill promoted by Douglas that allowed a south to north, Mobile

Mobile may refer to:

Places

* Mobile, Alabama, a U.S. port city

* Mobile County, Alabama

* Mobile, Arizona, a small town near Phoenix, U.S.

* Mobile, Newfoundland and Labrador

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Mobile ( ...

to Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

railroad to be financed by "federal land grants for the specific purpose of railroad construction". To satisfy Southern opposition to the general principle of federally supported internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, canal ...

, the land grants would first be transferred to the appropriate state or territorial government, which would oversee the final transfer to private developers.

By 1850, however, the majority of the South was not interested in exploiting its advantages in developing a transcontinental railroad or railroads in general. Businessmen like Gadsden, who advocated economic diversification, were in the minority. The Southern economy was based on cotton exports, and then-current transportation networks met the plantation system's needs. There was little home market for an intra-South trade. In the short term, the best use for capital was to invest it in more slaves and land rather than in taxing it to support canals, railroads, roads, or in dredging rivers. Historian Jere W. Roberson wrote:

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ( es, Tratado de Guadalupe Hidalgo), officially the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement between the United States of America and the United Mexican States, is the peace treaty that was signed on 2 ...

(1848) ended the Mexican–American War, but left issues affecting both sides that still needed to be resolved: possession of the Mesilla Valley

The Mesilla Valley is a geographic feature of Southern New Mexico and far West Texas. It was formed by repeated heavy spring floods of the Rio Grande.

Background

The fertile Mesilla Valley extends from Radium Springs, New Mexico, to the west s ...

, protection for Mexico from Indian raids, and the right of transit in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec

The Isthmus of Tehuantepec () is an isthmus in Mexico. It represents the shortest distance between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean. Before the opening of the Panama Canal, it was a major overland transport route known simply as the T ...

.

Mesilla Valley

The treaty provided for a joint commission, made up of a surveyor and commissioner from each country, to determine the final boundary between the United States and Mexico. The treaty specified that the Rio Grande Boundary would veer west eight miles (13 km) north of El Paso. The treaty was based on the attached 1847 copy of a twenty-five-year-old map. Surveys revealed that El Paso was further south and further west than the map showed. Mexico favored the map, but the United States put faith in the results of the survey. The disputed territory involved a few thousand square miles and about 3,000 residents; more significantly, it included the Mesilla Valley. Bordering the Rio Grande, the valley consisted of flat desert land measuring about , north to south, by , east to west. This valley was essential for the construction of a transcontinental railroad using a southern route. John Bartlett ofRhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the smallest U.S. state by area and the seventh-least populous, with slightly fewer than 1.1 million residents as of 2020, but it ...

, the United States negotiator, agreed to allow Mexico to retain the Mesilla Valley (setting the boundary at 32° 22′ N, north of the American claim 31° 52′ and at the easternmost part, also north of the Mexican-claimed boundary at 32° 15′) in exchange for a boundary that did not turn north until 110° W in order to include the Santa Rita Mountains

The Santa Rita Mountains ( O'odham: To:wa Kuswo Doʼag), located about 65 km (40 mi) southeast of Tucson, Arizona, extend 42 km (26 mi) from north to south, then trending southeast. They merge again southeastwards into the Pat ...

, which were believed to have rich copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkis ...

deposits, and some silver

Silver is a chemical element with the symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical ...

and gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile me ...

which had not yet been mined. Southerners opposed this alternative because of its implication for the railroad, but President Fillmore supported it. Southerners in Congress prevented any action on the approval of this separate border treaty and eliminated further funding to survey the disputed borderland. Robert B. Campbell, a pro-railroad politician from Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,765 ...

, later replaced Bartlett. Mexico asserted that the commissioners' determinations were valid and prepared to send in troops to enforce the unratified agreement.

Indian raids

Article XI of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo contained a guarantee that the United States would protect Mexicans by preventing cross-border raids by local Comanche and Apache tribes. At the time the treaty was ratified, Secretary of State James Buchanan had believed that the United States had both the commitment and resources to enforce this promise.. Historian

Article XI of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo contained a guarantee that the United States would protect Mexicans by preventing cross-border raids by local Comanche and Apache tribes. At the time the treaty was ratified, Secretary of State James Buchanan had believed that the United States had both the commitment and resources to enforce this promise.. Historian Richard Kluger

Richard Kluger (born 1934) is an American author who has won a Pulitzer Prize. He focuses his writing chiefly on society, politics and history. He has been a journalist and book publisher.

Early life and family

Born in Paterson, New Jersey, in Se ...

, however, described the difficulties of the task:

In the five years after approval of the Treaty, the United States spent $12 million (equivalent to $ in ) in this area, and General-in-Chief Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

estimated that five times that amount would be necessary to police the border. Mexican officials, frustrated with the failure of the United States to effectively enforce its guarantee, demanded reparations for the losses inflicted on Mexican citizens by the raids. The United States argued that the Treaty did not require any compensation nor did it require any greater effort to protect Mexicans than was expended in protecting its own citizens. During the Fillmore administration, Mexico claimed damages of $40 million (equivalent to $ in ) but offered to allow the U.S. to buy-out Article XI for $25 million ($) while President Fillmore proposed a settlement that was $10 million less ($).

Isthmus of Tehuantepec

During negotiations of the treaty, Americans had failed to secure the right of transit across theIsthmus of Tehuantepec

The Isthmus of Tehuantepec () is an isthmus in Mexico. It represents the shortest distance between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean. Before the opening of the Panama Canal, it was a major overland transport route known simply as the T ...

in southern Mexico. The idea of building a railroad here had been considered for a long time, connecting the Gulf of Mexico with the Pacific Ocean. In 1842 Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna sold the rights to build a railroad or canal across the isthmus. The deal included land grants wide along the right-of-way for future colonization and development. In 1847 a British bank bought the rights, raising U.S. fears of British colonization in the hemisphere, in violation of the precepts of the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile act ...

. United States interest in the right-of-way increased in 1848 after the gold strikes in the Sierra Nevada, which led to the California Gold Rush.; .

The Memphis commercial convention of 1849 recommended that the United States pursue the trans-isthmus route, since it appeared unlikely that a transcontinental railroad would be built anytime soon. Interests in Louisiana were especially adamant about this option, as they believed that any transcontinental railroad would divert commercial traffic away from the Mississippi and New Orleans, and they at least wanted to secure a southern route. Also showing interest was Peter A. Hargous of New York who ran an import-export business between New York and Vera Cruz. Hargous purchased the rights to the route for $25,000 (equivalent to $ in ), but realized that the grant had little value unless it was supported by the Mexican and American governments.

In Mexico, topographical officer George W. Hughes reported to Secretary of State John M. Clayton that a railroad across the isthmus was a "feasible and practical" idea. Clayton then instructed

The Memphis commercial convention of 1849 recommended that the United States pursue the trans-isthmus route, since it appeared unlikely that a transcontinental railroad would be built anytime soon. Interests in Louisiana were especially adamant about this option, as they believed that any transcontinental railroad would divert commercial traffic away from the Mississippi and New Orleans, and they at least wanted to secure a southern route. Also showing interest was Peter A. Hargous of New York who ran an import-export business between New York and Vera Cruz. Hargous purchased the rights to the route for $25,000 (equivalent to $ in ), but realized that the grant had little value unless it was supported by the Mexican and American governments.

In Mexico, topographical officer George W. Hughes reported to Secretary of State John M. Clayton that a railroad across the isthmus was a "feasible and practical" idea. Clayton then instructed Robert P. Letcher

Robert Perkins Letcher (February 10, 1788 – January 24, 1861) was a politician and lawyer from the US state of Kentucky. He served as a U.S. Representative, Minister to Mexico, and the 15th Governor of Kentucky. He also served in the Kentuc ...

, the minister to Mexico, to negotiate a treaty to protect Hargous' rights. The United States' proposal gave Mexicans a 20% discount on shipping, guaranteed Mexican rights in the zone, allowed the United States to send in military if necessary, and gave the United States most-favored-nation status for Mexican cargo fees. This treaty, however, was never finalized.

The Clayton–Bulwer Treaty between the United States and the United Kingdom, which guaranteed the neutrality of any such canal, was finalized in April 1850. Mexican negotiators refused the treaty because it would eliminate Mexico's ability to play the US and Britain against each other. They eliminated the right of the United States to unilaterally intervene militarily. The United States Senate approved the treaty in early 1851, but the Mexican Congress refused to accept the treaty..

In the meantime, Hargous proceeded as if the treaty would be approved eventually. Judah P. Benjamin

Judah Philip Benjamin, QC (August 6, 1811 – May 6, 1884) was a United States senator from Louisiana, a Cabinet officer of the Confederate States and, after his escape to the United Kingdom at the end of the American Civil War, an English ba ...

and a committee of New Orleans businessmen joined with Hargous and secured a charter from the Louisiana legislature to create the Tehuantepec Railroad Company. The new company sold stock and sent survey teams to Mexico. Hargous started to acquire land even after the Mexican legislature rejected the treaty, a move that led to the Mexicans canceling Hargous' contract to use the right of way. Hargous put his losses at $5 million (equivalent to $ in ) and asked the United States government to intervene. President Fillmore refused to do so.

Mexico sold the canal franchise, without the land grants, to A. G. Sloo and Associates in New York for $600,000 (equivalent to $ in ). In March 1853 Sloo contracted with a British company to build a railroad and sought an exclusive contract from the new Franklin Pierce Administration to deliver mail from New York to San Francisco. However, Sloo soon defaulted on bank loans and the contract was sold back to Hargous.

Final negotiations and ratification of the treaty of purchase

The Pierce administration, which took office in March 1853, had a strong pro-southern, pro-expansion mindset. It sent Louisiana Senator Pierre Soulé to Spain to negotiate the acquisition of Cuba. Pierce appointed expansionists John Y. Mason of Virginia and Solon Borland of Arkansas as ministers, respectively, toFrance

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

and Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the countr ...

. Pierce's Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis, was already on record as favoring a southern route for a transcontinental railroad, so southern rail enthusiasts had every reason to be encouraged.

The South as a whole, however, remained divided. In January 1853, Senator Thomas Jefferson Rusk

Thomas Jefferson Rusk (December 5, 1803July 29, 1857) was an early political and military leader of the Republic of Texas, serving as its first Secretary of War as well as a general at the Battle of San Jacinto. He was later a US politician and ...

of Texas introduced a bill to create two railroads, one with a northern route, and one with a southern route starting below Memphis on the Mississippi River. Under the Rusk legislation, the President would be authorized to select the specific termini and routes as well as the contractors who would build the railroads. Some southerners, however, worried that northern and central interests would leap ahead in construction and opposed any direct aid to private developers on constitutional grounds. Other southerners preferred the isthmian proposals. An amendment was added to the Rusk bill to prohibit direct aid, but southerners still split their vote in Congress and the amendment failed.

This rejection led to legislative demands, sponsored by William Gwin of California and Salmon P. Chase of Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

and supported by the railroad interests, for new surveys for possible routes. Gwin expected that a southern route would be approved—both Davis and Robert J. Walker, former Secretary of the Treasury, supported it. Both were stockholders in a Vicksburg-based railroad that planned to build a link to Texas to join up with the southern route. Davis argued that the southern route would have an important military application in the likely event of future troubles with Mexico.

Gadsden and Santa Anna

A treaty initiated in the Fillmore administration that would provide joint Mexican and United States protection for the Sloo grant was signed in Mexico on on March 21, 1853. At the same time that this treaty was received in Washington, Pierce learned that New Mexico Territorial Governor William C. Lane had issued a proclamation claiming the Mesilla Valley as part of New Mexico, leading to protests from Mexico. Pierce was also aware of efforts by France, through its consul in San Francisco, to acquire the Mexican state of Sonora.

Pierce recalled Lane in May and replaced him with David Meriwether of Kentucky. Meriwether was given orders to stay out of the Mesilla Valley until negotiations with Mexico could be completed. With the encouragement of Davis, Pierce also appointed James Gadsden as ambassador to Mexico, with specific instructions to negotiate with Mexico over the acquisition of additional territory. Secretary of State William L. Marcy gave Gadsden clear instructions: he was to secure the Mesilla Valley for the purposes of building a railroad through it, convince Mexico that the US had done its best regarding the Indian raids, and elicit Mexican cooperation in efforts by US citizens to build a canal or railroad across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Supporting the Sloo interests was not part of the instructions. Gadsden met with Santa Anna in Mexico City on September 25, 1853, to discuss the terms of the treaty.

The Mexican government was going through political and financial turmoil. In the process, Santa Anna had been returned to power about the same time that Pierce was inaugurated. Santa Anna was willing to deal with the United States because he needed money to rebuild the

A treaty initiated in the Fillmore administration that would provide joint Mexican and United States protection for the Sloo grant was signed in Mexico on on March 21, 1853. At the same time that this treaty was received in Washington, Pierce learned that New Mexico Territorial Governor William C. Lane had issued a proclamation claiming the Mesilla Valley as part of New Mexico, leading to protests from Mexico. Pierce was also aware of efforts by France, through its consul in San Francisco, to acquire the Mexican state of Sonora.

Pierce recalled Lane in May and replaced him with David Meriwether of Kentucky. Meriwether was given orders to stay out of the Mesilla Valley until negotiations with Mexico could be completed. With the encouragement of Davis, Pierce also appointed James Gadsden as ambassador to Mexico, with specific instructions to negotiate with Mexico over the acquisition of additional territory. Secretary of State William L. Marcy gave Gadsden clear instructions: he was to secure the Mesilla Valley for the purposes of building a railroad through it, convince Mexico that the US had done its best regarding the Indian raids, and elicit Mexican cooperation in efforts by US citizens to build a canal or railroad across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Supporting the Sloo interests was not part of the instructions. Gadsden met with Santa Anna in Mexico City on September 25, 1853, to discuss the terms of the treaty.

The Mexican government was going through political and financial turmoil. In the process, Santa Anna had been returned to power about the same time that Pierce was inaugurated. Santa Anna was willing to deal with the United States because he needed money to rebuild the Mexican Army

The Mexican Army ( es, Ejército Mexicano) is the combined land and air branch and is the largest part of the Mexican Armed Forces; it is also known as the National Defense Army.

The Army is under the authority of the Secretariat of National ...

for defense against the United States. He initially rejected the extension of the border further south to the Sierra Madre Mountains. He initially insisted on reparations for the damages caused by American Indian raids, but agreed to let an international tribunal resolve this. Gadsden realized that Santa Anna needed money and passed this information along to Secretary Marcy..

Marcy and Pierce responded with new instructions. Gadsden was authorized to purchase any of six parcels of land with a price fixed for each. The price would include the settlement of all Indian damages and relieve the United States from any further obligation to protect Mexicans. $50 million (equivalent to $ in ) would have bought the Baja California Peninsula and a large portion of its northwestern Mexican states while $15 million ($) was to buy the of desert necessary for the railroad plans.

"Gadsden's antagonistic manner" alienated Santa Anna. Gadsden had advised Santa Anna that "the spirit of the age" would soon lead the northern Mexican states to secede so he might as well sell them now. Mexico balked at any large-scale sale of territory. The Mexican President felt threatened by William Walker's attempt to capture Baja California

Baja California (; 'Lower California'), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Baja California ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Baja California), is a state in Mexico. It is the northernmost and westernmost of the 32 federal entities of Mex ...

with 50 troops and annex Sonora. Gadsden disavowed any government backing of Walker, who retreated to the U.S. and was placed on trial as a criminal.. Santa Anna worried that the US would allow further aggression against Mexican territory. Santa Anna needed to get as much money for as little territory as possible. When the United Kingdom rejected Mexican requests to assist in the negotiations, Santa Anna opted for the $15 million package (equivalent to $ in )..

Santa Anna signed the treaty on December 30, 1853, along with James Gadsden. Then the treaty was presented to the U.S. Senate for confirmation.

Ratification

Pierce and his cabinet began debating the treaty in January 1854. Although disappointed in the amount of territory secured and some of the terms, Pierce signed it, and submitted it to the Senate on February 10. Gadsden, however, suggested that northern Senators would block the treaty to deny the South a railroad.

The treaty needed a two-thirds vote in favor of ratification in the US Senate, where it met strong opposition. Anti-slavery senators opposed further acquisition of slave territory. Lobbying by speculators gave the treaty a bad reputation. Some Senators objected to furnishing Santa Anna financial assistance.

The treaty reached the Senate as that body focused on the debate over the

Pierce and his cabinet began debating the treaty in January 1854. Although disappointed in the amount of territory secured and some of the terms, Pierce signed it, and submitted it to the Senate on February 10. Gadsden, however, suggested that northern Senators would block the treaty to deny the South a railroad.

The treaty needed a two-thirds vote in favor of ratification in the US Senate, where it met strong opposition. Anti-slavery senators opposed further acquisition of slave territory. Lobbying by speculators gave the treaty a bad reputation. Some Senators objected to furnishing Santa Anna financial assistance.

The treaty reached the Senate as that body focused on the debate over the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by ...

. On April 17, after much debate, the Senate voted 27 to 18 in favor of the treaty, falling three votes short of the necessary two-thirds majority. After this defeat, Secretary Davis and southern Senators pressed Pierce to add more provisions to the treaty including:

* protection for the Sloo grant;

* a requirement that Mexico "protect with its whole power the prosecution, preservation, and security of the work eferring to the isthmian canal;

* permission for the United States to intervene unilaterally "when it may feel sanctioned and warranted by the public or international law"; and

* a reduction of the territory to be acquired by to the final size of , and dropping the price to $10 million (equivalent to $ in ) from $15 million ($).

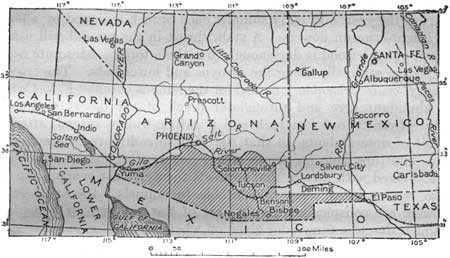

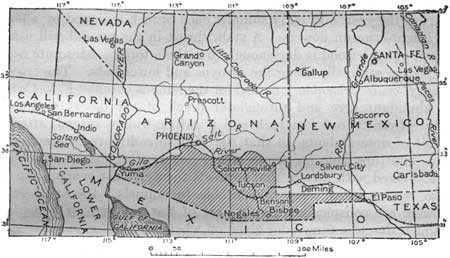

The land area included in the treaty is shown in the map at the head of the article, and in the national map in this section.

This version of the treaty successfully passed the US Senate April 25, 1854, by a vote of 33 to 12. The reduction in territory was an accommodation of northern senators who opposed the acquisition of additional slave territory. In the final vote, northerners split 12 to 12. Gadsden took the revised treaty back to Santa Anna, who accepted the changes. The treaty went into effect June 30, 1854.

While the land was available for construction of a southern railroad, the issue had become too strongly associated with the sectional debate over slavery to receive federal funding. Roberson wrote:.

The effect was such that railroad development, which accelerated in the North, stagnated in the South..

Post-ratification controversy

As originally envisioned, the purchase would have encompassed a much larger region, extending far enough south to include most of the currentMexican states

The states of Mexico are first-level administrative territorial entities of the country of Mexico, which is officially named United Mexican States. There are 32 federal entities in Mexico (31 states and the capital, Mexico City, as a separate en ...

of Baja California

Baja California (; 'Lower California'), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Baja California ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Baja California), is a state in Mexico. It is the northernmost and westernmost of the 32 federal entities of Mex ...

, Baja California Sur, Coahuila, Chihuahua, Sonora, Nuevo León, and Tamaulipas

Tamaulipas (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Tamaulipas ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Tamaulipas), is a state in the northeast region of Mexico; one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Federal Entiti ...

. The Mexican people opposed such boundaries, as did anti-slavery Americans, who saw the purchase as acquisition of more slave territory. Even the sale of a relatively small strip of land angered the Mexican people, who saw Santa Anna's actions as a betrayal of their country. They watched in dismay as he squandered the funds generated by the Purchase. Contemporary Mexican historians continue to view the deal negatively and believe that it has defined the American–Mexican relationship in a deleterious way.

The purchased lands were initially appended to the existing New Mexico Territory. To help control the new land, the US Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

established Fort Buchanan on Sonoita Creek

Sonoita Creek is a tributary stream of the Santa Cruz River in Santa Cruz County, Arizona. It originates near and takes its name from the abandoned Pima mission in the high valley near Sonoita. It flows steadily for the first of its westwa ...

in present-day southern Arizona on November 17, 1856. The difficulty of governing the new areas from the territorial capital at Santa Fe led to efforts as early as 1856 to organize a new territory out of the southern portion. Many of the early settlers in the region were, however, pro-slavery and sympathetic to the South, resulting in an impasse in Congress as to how best to reorganize the territory.

The shifting of the course of the Rio Grande would cause a later dispute over the boundary between Purchase lands and those of the state of Texas, known as the Country Club Dispute. Pursuant to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the Gadsden Treaty and subsequent treaties, the International Boundary and Water Commission

The International Boundary and Water Commission ( es, links=no, Comisión Internacional de Límites y Aguas) is an international body created by the United States and Mexico in 1889 to apply the rules for determining the location of their intern ...

was established in 1889 to maintain the border. Pursuant to still later treaties, the IBWC expanded its duties to allocation of river waters between the two nations, and provided for flood control and water sanitation. Once viewed as a model of international cooperation, in recent decades the IBWC has been heavily criticized as an institutional anachronism, by-passed by modern social, environmental, and political issues.

Growth of the region after 1854

Army control

The residents of the area gained full US citizenship and slowly assimilated into American life over the next half-century. The principal threat to the peace and security of settlers and travelers in the area was raids by Apache Indians. The US Army took control of the purchase lands in 1854 but not until 1856 were troops stationed in the troubled region. In June 1857 it established Fort Buchanan south of the Gila at the head of the Sonoita Creek Valley. The fort protected the area until it was evacuated and destroyed in July 1861. The new stability brought miners and ranchers. By the late 1850s mining camps and military posts had not only transformed the Arizona countryside; they had also generated new trade linkages to the state of Sonora, Mexico. Magdalena, Sonora, became a supply center for Tubac; wheat from nearby Cucurpe fed the troops at Fort Buchanan; and the town of Santa Cruz sustained the Mowry mines, just miles to the north.Civil War

In 1861, during theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

formed the Confederate Territory of Arizona, including in the new territory mainly areas acquired by the Gadsden Purchase. In 1863, using a north-to-south dividing line, the Union created its own Arizona Territory out of the western half of the New Mexico Territory. The new American Arizona Territory also included most of the lands acquired in the Gadsden Purchase. This territory would be admitted into the Union as the State of Arizona on February 14, 1912, the last area of the Lower 48 States

The contiguous United States (officially the conterminous United States) consists of the 48 adjoining U.S. states and the Federal District of the United States of America. The term excludes the only two non-contiguous states, Alaska and Hawaii ...

to receive statehood.

Social development

After the Gadsden Purchase, southern Arizona's social elite, including theEstevan Ochoa

Estevan Ochoa (March 17, 1831 – October 27, 1888) was a Mexican-born American businessman and politician who participated in the creation of the Arizona Territory.

Biography

Ochoa was born to Jesus Ochoa in Chihuahua, Mexico on March 17, 183 ...

, Mariano Samaniego, and Leopoldo Carillo families, remained primarily Mexican American until the coming of the railroad in the 1880s. When the Sonora Exploring and Mining Company opened silver mines in southern Arizona, it sought to employ educated, middle-class Americans who shared a work ethic and leadership abilities to operate the mines. A biographical analysis of some 200 of its employees, classed as capitalists, managers, laborers, and general service personnel, reveals that the resulting work force included Europeans, Americans, Mexicans, and Indians. This mixture failed to stabilize the remote area, which lacked formal social, political, and economic organization in the years from the Gadsden Purchase to the Civil War.

Economic development

From the late 1840s into the 1870s, Texas stockmen drove their beef cattle through southern Arizona on the Texas–California trail. Texans were impressed with the grazing possibilities offered by the Gadsden Purchase country of Arizona. In the last third of the century, they moved their herds into Arizona and established the range cattle industry there. The Texans contributed their proven range methods to the new grass country of Arizona, but also brought their problems as well. Texas rustlers brought lawlessness, poor management resulted in overstocking, and carelessness introduced destructive diseases. But these difficulties did force laws and associations in Arizona to curb and resolve them. The Anglo-American cattleman frontier in Arizona was an extension of the Texas experience. When the Arizona Territory was formed in 1863 from the southern portion of the New Mexico Territory,Pima County

Pima County ( ) is a county in the south central region of the U.S. state of Arizona. As of the 2020 census, the population was 1,043,433, making it Arizona's second-most populous county. The county seat is Tucson, where most of the populati ...

and later Cochise County

Cochise County () is a county in the southeastern corner of the U.S. state of Arizona. It is named after the Native American chief Cochise.

The population was 125,447 at the 2020 census. The county seat is Bisbee and the most populous city is ...

—created from the easternmost portion of Pima County in January 1881—were subject to ongoing border-related conflicts. The area was characterized by rapidly growing boom towns, ongoing Apache raids, smuggling and cattle rustling across the United States-Mexico border, growing ranching operations, and the expansion of new technologies in mining, railroading, and telecommunications.

In the 1860s conflict between the Apaches and the Americans was at its height. Until 1886, almost constant warfare existed in the region adjacent to the Mexican border. The illegal cattle operations kept beef prices in the border region lower and provided cheap stock that helped small ranchers get by. Many early Tombstone, Arizona

Tombstone is a historic city in Cochise County, Arizona, United States, founded in 1877 by prospector Ed Schieffelin in what was then Pima County, Arizona Territory. It became one of the last boomtowns in the American frontier. The town gr ...

residents looked the other way when it was "only Mexicans" being robbed.

Outlaws derisively called "The Cowboys

''The Cowboys'' is a 1972 American Western film starring John Wayne, Roscoe Lee Browne, and Bruce Dern, and featuring Colleen Dewhurst and Slim Pickens. It was the feature film debut of Robert Carradine. Based on the 1971 novel of the same name ...

" frequently robbed stagecoaches and brazenly stole cattle in broad daylight, scaring off the legitimate cowboys watching the herds. Bandits used the border between the United States and Mexico to raid across in one direction and take sanctuary in the other. In December 1878, and again the next year, Mexican authorities complained about the "Cowboy" outlaws who stole Mexican beef and resold it in Arizona. The '' Arizona Citizen'' reported that both U.S. and Mexican bandits were stealing horses from the Santa Cruz Valley and selling them in Sonora. Arizona Territorial Governor Frémont investigated the Mexican government's allegations and accused them in turn of allowing outlaws to use Sonora as a base of operations for raiding into Arizona.

In the 1870s and 1880s there was considerable tension in the region—between the rural residents, who were for the most part Democrats from the agricultural South, and town residents and business owners, who were largely Republicans from the industrial Northeast and Midwest. The tension culminated in what has been called the Cochise County feud, and the Earp-Clanton feud, which ended with the historic Gunfight at the O.K. Corral

The gunfight at the O.K. Corral was a thirty-second shootout between law enforcement officer, lawmen led by Virgil Earp and members of a loosely organized group of outlaws called the Cochise County Cowboys, Cowboys that occurred at about 3: ...

and Wyatt Earp

Wyatt Berry Stapp Earp (March 19, 1848 – January 13, 1929) was an American lawman and gambler in the American West, including Dodge City, Deadwood, and Tombstone. Earp took part in the famous gunfight at the O.K. Corral, during which l ...

's Vendetta Ride.

The Gadsden purchase resulted in the division of the Tohono Oʼodham Nation

The Tohono Oʼodham Nation is the collective government body of the Tohono Oʼodham tribe in the United States. The Tohono Oʼodham Nation governs four separate pieces of land with a combined area of , approximately the size of Connecticut and th ...

and its ancestral lands by the new international border. This disrupted traditional migratory practices and transportation of materials and goods essential for their spirituality, economy and traditional culture. Nine communities are on the Mexican side of this boundary. Conflicts have arisen mainly in the 21st century with stronger enforcement of customs laws at the border.

Railroad development

In 1846, James Gadsden, then president of the

In 1846, James Gadsden, then president of the South Carolina Railroad

The South Carolina Rail Road Company was a railroad company that operated in South Carolina from 1843 to 1894, when it was succeeded by the Southern Railway. It was formed in 1844 by the merger of the South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company (SC ...

, proposed building a transcontinental railroad linking the Atlantic at Charleston with the Pacific at San Diego. Federal and private surveys by Lt. John G. Parke and Andrew B Gray proved the feasibility of the southern transcontinental route, but sectional strife and the Civil War delayed construction of the proposed railroad. The Southern Pacific Railroad from Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, largest city in the U.S. state, state of California and the List of United States cities by population, sec ...

reached Yuma, Arizona, in 1877, Tucson, Arizona

, "(at the) base of the black ill

, nicknames = "The Old Pueblo", "Optics Valley", "America's biggest small town"

, image_map =

, mapsize = 260px

, map_caption = Interactive map ...

in March 1880, Deming, New Mexico in December 1880, and El Paso

El Paso (; "the pass") is a city in and the seat of El Paso County in the western corner of the U.S. state of Texas. The 2020 population of the city from the U.S. Census Bureau was 678,815, making it the 23rd-largest city in the U.S., the s ...

in May 1881, the first railroad across the Gadsden Purchase.

At the same time, 1879–1881, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad was building across New Mexico and met the Southern Pacific at Deming, New Mexico March 7, 1881, completing the second transcontinental railroad (the first, the central transcontinental, was completed May 10, 1869 at Promontory Summit, Utah). Acquiring trackage rights over the SP, from Deming to Benson, the Santa Fe then built a line southwest to Guaymas, Sonora, Mexico, completed October 1882, as its first outlet to the Pacific. This line was later sold to the Southern Pacific. The Southern Pacific continued building east from El Paso, completing a junction with the Texas & Pacific in December 1881, and finally in 1883, its own southern transcontinental, the Sunset Route, California to New Orleans, Atlantic waters to the Pacific. These railroads caused an early 1880s mining boom in such locales as Tombstone, Arizona

Tombstone is a historic city in Cochise County, Arizona, United States, founded in 1877 by prospector Ed Schieffelin in what was then Pima County, Arizona Territory. It became one of the last boomtowns in the American frontier. The town gr ...

, Bisbee, Arizona

Bisbee is a city in and the county seat of Cochise County in southeastern Arizona, United States. It is southeast of Tucson and north of the Mexican border. According to the 2020 census, the population of the town was 4,923, down from 5,575 ...

, and Santa Rita, New Mexico

Santa Rita is a ghost town in Grant County in the U.S. state of New Mexico. The site of Chino copper mine, Santa Rita was located fifteen miles east of Silver City.

History

Copper mining in the area began late in the Spanish colonial period, bu ...

, the latter two world class copper producers. From Bisbee, a third sub-transcontinental was built across the Gadsden Purchase, the El Paso and Southwestern Railroad

The El Paso and Southwestern Railroad began in 1888 as the Arizona and South Eastern Railroad, a short line serving copper mines in southern Arizona. Over the next few decades, it grew into a 1200-mile system that stretched from Tucumcari, New ...

, to El Paso by 1905, then to a link with the Rock Island line to form the Golden State Route. The EP&SW was sold to the Southern Pacific in the early 1920s.

The portion of the Southern Pacific in Arizona was originally largely in the Gadsden Purchase but the western part was later rerouted north of the Gila River to serve the city of Phoenix (as part of the agreement in purchasing the EP&SW). The portion in New Mexico runs largely through the territory that had been disputed between Mexico and the United States after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo had gone into effect, and before the time of the Gadsden Purchase. The Santa Fe Railroad Company also completed a railroad across Northern Arizona

Northern Arizona is an unofficial, colloquially-defined region of the U.S. state of Arizona. Generally consisting of Apache, Coconino, Mohave, Navajo, and Gila counties, the region is geographically dominated by the Colorado Plateau, the sout ...

, via Holbrook Holbrook may refer to:

Places

England

*Holbrook, Derbyshire, a village

* Holbrook, Somerset, a hamlet in Charlton Musgrove

* Holbrook, Sheffield, South Yorkshire, a former mining village in Mosborough ward, now known as Halfway

*Holbrook, Suffolk, ...

, Winslow Winslow may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Winslow, Buckinghamshire, England, a market town and civil parish

* Winslow Rural District, Buckinghamshire, a rural district from 1894 to 1974

United States and Canada

* Rural Municipality of Winslo ...

, Flagstaff and Kingman in August 1883. These two transcontinental railroads, the Southern Pacific (now part of the Union Pacific Railroad

The Union Pacific Railroad , legally Union Pacific Railroad Company and often called simply Union Pacific, is a freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Paci ...

) and the Santa Fe (now part of the BNSF

BNSF Railway is one of the largest freight railroads in North America. One of seven North American Class I railroads, BNSF has 35,000 employees, of track in 28 states, and nearly 8,000 locomotives. It has three transcontinental routes that ...

), are among the busiest rail lines in the United States.

During the early twentieth century, a number of short-lines usually associated with mining booms were built in the Gadsden Purchase to Ajo, Silverbell, Twin Buttes, Courtland, Gleeson, Arizona, Shakespeare, New Mexico, and other mine sites. Most of these railroads have been abandoned.

The remainder of the Gila Valley pre-Purchase border area was traversed by the Arizona Eastern Railway by 1899 and the Copper Basin Railway by 1904. Excluded was a section in the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation, from today's San Carlos Lake

San Carlos Lake was formed by the construction of the Coolidge Dam and is rimmed by of shoreline. The lake is located within the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation, and is thus subject to tribal regulations.

After it was built, the reservoi ...

to Winkelman

Winkelman is a town in Gila and Pinal counties in Arizona, United States. According to the 2010 census, the population of the town was 353, all of whom lived in Gila County.

History

The community was named after Peter Winkelman, a local catt ...

at the mouth of the San Pedro River, including the Needle's Eye Wilderness. The section of US Highway 60 about between Superior and Miami

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a coastal metropolis and the county seat of Miami-Dade County in South Florida, United States. With a population of 442,241 at ...

via Top-of-the-World (this road segment is east of Phoenix, in the Tonto National Forest passing through a mountainous region), takes an alternate route (17.4 road miles) between the Magma Arizona Railroad

The Magma Arizona Railroad was built by the Magma Copper Company and operated from 1915 to 1997.

The railroad was originally built as a narrow gauge line, but was converted to in 1923. Originally headquartered in Superior, Arizona, the com ...

and the Arizona Eastern Railway railheads on each side of this gap. This highway is well north of the Gadsden Purchase. Given the elevations of those three places, at least a 3% grade

Grade most commonly refers to:

* Grade (education), a measurement of a student's performance

* Grade, the number of the year a student has reached in a given educational stage

* Grade (slope), the steepness of a slope

Grade or grading may also ref ...