Treaty of Bärwalde on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Treaty of Bärwalde (french: Traité de Barwalde; sv, Fördraget i Bärwalde; german: Vertrag von Bärwalde), signed on 23 January 1631, was an agreement by

The

The  In June 1630, nearly 18,000 Swedish troops landed in the

In June 1630, nearly 18,000 Swedish troops landed in the

From 1628 to 1630, France fought a proxy war with Spain over Mantua, in Northern Italy. Hoping to use Sweden to occupy Spanish forces in Germany, in 1629 Richelieu appointed Hercule de Charnacé French envoy in the Baltic region, with responsibility for negotiating a deal with Gustavus. Talks progressed slowly; de Charnacé quickly concluded the Swedish monarch was too powerful a character to be easily controlled and urged caution. One major issue was the insistence by Gustavus that

From 1628 to 1630, France fought a proxy war with Spain over Mantua, in Northern Italy. Hoping to use Sweden to occupy Spanish forces in Germany, in 1629 Richelieu appointed Hercule de Charnacé French envoy in the Baltic region, with responsibility for negotiating a deal with Gustavus. Talks progressed slowly; de Charnacé quickly concluded the Swedish monarch was too powerful a character to be easily controlled and urged caution. One major issue was the insistence by Gustavus that

The haste with which the treaty was agreed concealed serious weaknesses, which soon became apparent. In May 1631, an army of the Catholic League under the Bavarian

The haste with which the treaty was agreed concealed serious weaknesses, which soon became apparent. In May 1631, an army of the Catholic League under the Bavarian

Scan of the treaty (IEG Mainz)

{{Thirty Years' War treaties Thirty Years' War treaties 1631 in Europe Bärwalde 1631 treaties Bärwalde 1631 in France 1631 in Sweden France–Sweden relations

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

to provide Sweden financial support, following its intervention in the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of battle ...

.

This was in line with Cardinal Richelieu's policy of avoiding direct French involvement, but weakening Habsburg Austria by backing its opponents. Under its terms, Gustavus Adolphus agreed to maintain an army of 36,000 troops, in return for an annual payment of 400,000 Reichsthaler

The ''Reichsthaler'' (; modern spelling Reichstaler), or more specifically the ''Reichsthaler specie'', was a standard thaler silver coin introduced by the Holy Roman Empire in 1566 for use in all German states, minted in various versions for the ...

s, for a period of five years.

France continued their support after Gustavus was killed at Lützen in November 1632. When the Swedes were defeated at Nördlingen

Nördlingen (; Swabian: ''Nearle'' or ''Nearleng'') is a town in the Donau-Ries district, in Swabia, Bavaria, Germany, with a population of approximately 20,674. It is located approximately east of Stuttgart, and northwest of Munich. It was b ...

in September 1634, most of their German allies made peace in the Treaty of Prague. Richelieu decided to intervene directly; in 1635, the Franco-Swedish Treaty of Compiègne replaced that agreed at Bärwalde.

Background

Thirty Years War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of battl ...

began in 1618 when the Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

Frederick Frederick may refer to:

People

* Frederick (given name), the name

Nobility

Anhalt-Harzgerode

*Frederick, Prince of Anhalt-Harzgerode (1613–1670)

Austria

* Frederick I, Duke of Austria (Babenberg), Duke of Austria from 1195 to 1198

* Frederick ...

, ruler of the Electoral Palatinate

The Electoral Palatinate (german: Kurpfalz) or the Palatinate (), officially the Electorate of the Palatinate (), was a state that was part of the Holy Roman Empire. The electorate had its origins under the rulership of the Counts Palatine of ...

, accepted the crown of Bohemia. Many Germans remained neutral, viewing it as an inheritance dispute within the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

, and Emperor Ferdinand quickly suppressed the Bohemian Revolt

The Bohemian Revolt (german: Böhmischer Aufstand; cs, České stavovské povstání; 1618–1620) was an uprising of the Bohemian estates against the rule of the Habsburg dynasty that began the Thirty Years' War. It was caused by both relig ...

. However, Imperial forces then invaded the Palatinate, forcing Frederick into exile.

Depriving Frederick of his inheritance changed the nature and extent of the war, as it potentially threatened other German princes. This concern increased after Ferdinand passed the 1629 Edict of Restitution

The Edict of Restitution was proclaimed by Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor in Vienna, on 6 March 1629, eleven years into the Thirty Years' War. Following Catholic League (German), Catholic military successes, Ferdinand hoped to restore control ...

, which required all church properties transferred since 1552 be restored to their original owners; in nearly every case, this meant from Protestants to the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, effectively undoing the 1555 Peace of Augsburg. In addition, Ferdinand financed the Imperial army by allowing it to plunder the territories they passed through, including those of his allies.

The combination bolstered Protestant resistance within the Empire, and drew in external players, concerned by the prospect of a Catholic Counter Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also called the Catholic Reformation () or the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation. It began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) a ...

. In 1625, Christian IV of Denmark

Christian IV (12 April 1577 – 28 February 1648) was King of Denmark and Norway and Duke of Holstein and Schleswig from 1588 until his death in 1648. His reign of 59 years, 330 days is the longest of Danish monarchs and Scandinavian mon ...

landed in Northern Germany and had some success, before forced to withdraw in 1629. This led to intervention by Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, partly driven by a genuine desire to support his Protestant co-religionists, but also to ensure control of the Baltic trade

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

* Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originati ...

that provided much of Sweden's income.

In June 1630, nearly 18,000 Swedish troops landed in the

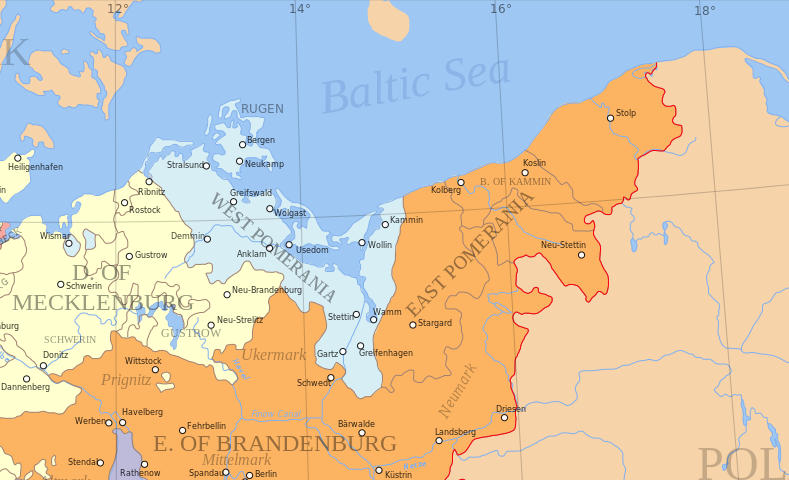

In June 1630, nearly 18,000 Swedish troops landed in the Duchy of Pomerania

The Duchy of Pomerania (german: Herzogtum Pommern; pl, Księstwo Pomorskie; Latin: ''Ducatus Pomeraniae'') was a duchy in Pomerania on the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, ruled by dukes of the House of Pomerania (''Griffins''). The country ha ...

, occupied by Wallenstein since 1627. Gustavus signed an alliance

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

with Bogislaw XIV, Duke of Pomerania

Bogislaw XIV (31 March 1580 – 10 March 1637) was the last Duke of Pomerania. He was also the Lutheran administrator of the Prince-Bishopric of Cammin.

Biography

Bogislaw was born in Barth as a member of the House of Pomerania. He was the thir ...

, securing his interests in Pomerania against the Catholic Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi- confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Poland and Lithuania ru ...

, another Baltic competitor linked to Ferdinand by family and religion.

Expectations of widespread support proved unrealistic; by the end of 1630, the only new Swedish ally was the Imperial town of Magdeburg

Magdeburg (; nds, label=Low Saxon, Meideborg ) is the capital and second-largest city of the German state Saxony-Anhalt. The city is situated at the Elbe river.

Otto I, the first Holy Roman Emperor and founder of the Archdiocese of Magdebu ...

, then besieged by the Catholic League. Despite the devastation inflicted on their territories by Imperial soldiers, Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a landlocked state of ...

and Brandenburg-Prussia were reluctant to back the Swedes. Both had their own ambitions in Pomerania, which clashed with those of Gustavus, while previous experience showed inviting external powers into the Empire was easier than getting them to leave.

Although the Swedes expelled the Imperials, this simply replaced one set of plunderers with another; Gustavus could not support so large an army, and his unpaid and unfed troops became increasingly mutinous and ill-disciplined. In January 1631, John George of Saxony hosted a conference of German Protestant states at Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as ...

, hoping to create a neutrality pact. Gustavus responded by advancing through Brandenburg, as far as Bärwalde, on the Oder, where he set up camp. This secured his rear before moving onto Magdeburg, while making a clear point to those meeting in Leipzig.

Negotiations

For much of the 16th and 17th centuries, Europe was dominated by the rivalry betweenFrance

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

and the Habsburgs, rulers of Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

and the Holy Roman Empire. During the 1620s, France was divided by renewed religious wars

A religious war or a war of religion, sometimes also known as a holy war ( la, sanctum bellum), is a war which is primarily caused or justified by differences in religion. In the modern period, there are frequent debates over the extent to wh ...

and Cardinal Richelieu, chief minister from 1624 to 1642, avoided open conflict with the Habsburgs. Instead, he financed their opponents, including the Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

, the Ottomans, and Danish intervention in the Thirty Years War.

From 1628 to 1630, France fought a proxy war with Spain over Mantua, in Northern Italy. Hoping to use Sweden to occupy Spanish forces in Germany, in 1629 Richelieu appointed Hercule de Charnacé French envoy in the Baltic region, with responsibility for negotiating a deal with Gustavus. Talks progressed slowly; de Charnacé quickly concluded the Swedish monarch was too powerful a character to be easily controlled and urged caution. One major issue was the insistence by Gustavus that

From 1628 to 1630, France fought a proxy war with Spain over Mantua, in Northern Italy. Hoping to use Sweden to occupy Spanish forces in Germany, in 1629 Richelieu appointed Hercule de Charnacé French envoy in the Baltic region, with responsibility for negotiating a deal with Gustavus. Talks progressed slowly; de Charnacé quickly concluded the Swedish monarch was too powerful a character to be easily controlled and urged caution. One major issue was the insistence by Gustavus that Frederick V Frederick V or Friedrich V may refer to:

* Frederick V, Duke of Swabia (1164–1170)

*Frederick V, Count of Zollern (d.1289)

*Frederick V, Burgrave of Nuremberg (c. 1333–1398), German noble

*Frederick V of Austria (1415–1493), or Frederick III ...

be restored as ruler of the Palatinate, currently occupied by another French ally, Maximilian of Bavaria.

The October 1630 Treaty of Ratisbonne concluded the Mantuan War in France's favour but in return, French negotiators undertook not to agree alliances with members of the Holy Roman Empire without Ferdinand's approval. Doing so would undermine the entire basis of French foreign policy; Louis XIII

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown ...

refused to ratify the deal, leading to an internal power struggle between Richelieu and the Queen Mother, Marie de Medici

Marie de' Medici (french: link=no, Marie de Médicis, it, link=no, Maria de' Medici; 26 April 1575 – 3 July 1642) was Queen of France and Navarre as the second wife of King Henry IV of France of the House of Bourbon, and Regent of the Kingdom ...

. At one point, it was widely believed he had been dismissed, an event known as the Day of the Dupes

Day of the Dupes (in french: la journée des Dupes) is the name given to a day in November 1630 on which the enemies of Cardinal Richelieu mistakenly believed that they had succeeded in persuading King Louis XIII of France to dismiss Richelieu fr ...

.

Although Richelieu triumphed over his domestic opponents, Swedish support became even more important, since as an external player it was not subject to the restrictions of Ratisbonne. De Charnacé was instructed to agree a treaty as soon as possible; after discussions with the Swedish diplomats, Gustav Horn and Johan Banér

Johan Banér (23 June 1596 – 10 May 1641) was a Swedish field marshal in the Thirty Years' War.

Early life

Johan Banér was born at Djursholm Castle in Uppland. As a four-year-old he was forced to witness how his father, the Privy Councillo ...

, it was signed at Bärwalde on 23 January 1631.

Terms

The stated purpose of the agreement was securing theBaltics

The Baltic states, et, Balti riigid or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term, which currently is used to group three countries: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone, ...

, and ensuring freedom of trade, including French trading privileges in the Øresund strait. Sweden agreed to maintain an army of 36,000 in Germany, of which 6,000 were cavalry; to support this force, France agreed to pay 400,000 Reichstaler

The ''Reichsthaler'' (; modern spelling Reichstaler), or more specifically the ''Reichsthaler specie'', was a standard thaler silver coin introduced by the Holy Roman Empire in 1566 for use in all German states, minted in various versions for the ...

or one million livres per year, plus an additional 120,000 Reichstalers for 1630. These subsidies

A subsidy or government incentive is a form of financial aid or support extended to an economic sector (business, or individual) generally with the aim of promoting economic and social policy. Although commonly extended from the government, the ter ...

were less than 2% of the total French state budget, but over 25% of the Swedish.

Gustavus promised to comply with Imperial laws on religion, allow freedom of worship for Catholics and respect the neutrality of Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

and the lands of the Catholic League. Both parties agreed not to seek a separate peace and the period of the treaty was set at five years.

Aftermath

The haste with which the treaty was agreed concealed serious weaknesses, which soon became apparent. In May 1631, an army of the Catholic League under the Bavarian

The haste with which the treaty was agreed concealed serious weaknesses, which soon became apparent. In May 1631, an army of the Catholic League under the Bavarian Count Tilly

Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly ( nl, Johan t'Serclaes Graaf van Tilly; german: Johann t'Serclaes Graf von Tilly; french: Jean t'Serclaes de Tilly ; February 1559 – 30 April 1632) was a field marshal who commanded the Catholic League (Ge ...

sacked the Protestant town of Magdeburg

Magdeburg (; nds, label=Low Saxon, Meideborg ) is the capital and second-largest city of the German state Saxony-Anhalt. The city is situated at the Elbe river.

Otto I, the first Holy Roman Emperor and founder of the Archdiocese of Magdebu ...

. Over 20,000 were alleged to have died in the most serious atrocity of the entire war, increasing the bitterness of the conflict and leading to intervention by other Protestant states. Gustavus embarked on a series of stunning military victories, and Protestant retribution for Magdeburg became a considerable embarrassment for Richelieu, a Cardinal of the Catholic Church

A cardinal ( la, Sanctae Romanae Ecclesiae cardinalis, literally 'cardinal of the Holy Roman Church') is a senior member of the clergy of the Catholic Church. Cardinals are created by the ruling pope and typically hold the title for life. Col ...

.

Under the May 1631 Franco-Bavarian Treaty of Fontainebleau, Richelieu agreed to provide Maximilian military support if attacked by any other party. In theory, it did not conflict with the terms of Bärwalde, since Gustavus undertook to respect Bavarian and Catholic League neutrality. In practice, his obligation applied only so long as their compliance and as Richelieu pointed out to Maximilian, even Tilly's presence at Magdeburg violated that neutrality.

The poorly worded Bärwalde treaty gave Gustavus a great deal of freedom, while Magdeburg brought him support from the Dutch and England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

among others. This made him increasingly independent of French control; his upward trajectory ended only with his death at Lützen in November 1632. Swedish intervention continued with French support, until defeat at Nördlingen

Nördlingen (; Swabian: ''Nearle'' or ''Nearleng'') is a town in the Donau-Ries district, in Swabia, Bavaria, Germany, with a population of approximately 20,674. It is located approximately east of Stuttgart, and northwest of Munich. It was b ...

in September 1634; this forced the Swedish army to temporarily retreat, while most of their German allies made peace with Emperor Ferdinand in the 1635 Treaty of Prague.

Combined with rumours of a proposed Austro-Spanish offensive in the Spanish Netherlands

Spanish Netherlands (Spanish: Países Bajos Españoles; Dutch: Spaanse Nederlanden; French: Pays-Bas espagnols; German: Spanische Niederlande.) (historically in Spanish: ''Flandes'', the name "Flanders" was used as a ''pars pro toto'') was the H ...

, Louis XIII

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown ...

and Richelieu now decided on direct intervention. In early 1635, they declared war on Spain, beginning the 1635 to 1659 Franco-Spanish War, and agreed the Treaty of Compiègne

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal pers ...

with Sweden, an alliance against Emperor Ferdinand. This continued until the 1648 Peace of Westphalia, which confirmed the acquisition of Swedish Pomerania; the wording was ambiguous and only finalised by the Treaty of Stettin (1653)

The Treaty of Stettin (german: Grenzrezeß von Stettin) of 4 May 1653Heitz (1995), p.232 settled a dispute between Brandenburg and Sweden, who both claimed succession in the Duchy of Pomerania after the extinction of the local House of Pomerania ...

. With the exception of some territorial adjustments in favour of Brandenburg, Sweden retained this territory until 1815.

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * *External links

Scan of the treaty (IEG Mainz)

{{Thirty Years' War treaties Thirty Years' War treaties 1631 in Europe Bärwalde 1631 treaties Bärwalde 1631 in France 1631 in Sweden France–Sweden relations