Transport Revolution on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of transport is largely one of technological

The first earth tracks were created by humans carrying goods and often followed

The first earth tracks were created by humans carrying goods and often followed

The history of rail transportation dates back nearly 500 years and includes systems with man or horsepower and

The history of rail transportation dates back nearly 500 years and includes systems with man or horsepower and

In the Stone Age, primitive boats developed to permit navigation of rivers and for fishing in rivers and off the coast. It has been argued that boats suitable for a significant sea crossing were necessary for people to reach Australia an estimated 40,000-45,000 years ago. With the development of

In the Stone Age, primitive boats developed to permit navigation of rivers and for fishing in rivers and off the coast. It has been argued that boats suitable for a significant sea crossing were necessary for people to reach Australia an estimated 40,000-45,000 years ago. With the development of

Polynesian double-hulled sailing vessels

with advanced rigging were used between 1,300 BC and 900 BC by the Polynesian progeny of the

http://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb.31038.0001.001 was proposed by Frederic Mauro, but the early existence of it was already observed by Dudley North in the year 1691. This world market of trade, as well as the flow of finances throughout, spanned out an interconnected throughout the entire globe, permitted the intersectoral and intersectional regional divisions of both generated competition, and labor.Locakard, Craig. "‘The Sea Common to All’: Maritime Frontiers, Port Cities, and Chinese Traders in the Southeast Asian Age of Commerce, ca. 1400–1750." ''Journal of World History'' 21, no. 2 (June 2010): 219–247. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20752948

Through the water frontier, many people throughout history have traveled by water as much as they have by land. Along with this, quite a large number of individuals relied on the sea and maritime trade, raiding, piracy, or smuggling for survival. Littoral peoples, reflecting symbiosis of both land and sea, would often have more in common with one another than they would with their neighboring islands. Throughout centuries in the past, water supplied the cheapest, and sometimes the only means of transporting bulk materials on a large scale, and it was also the most secure way to ensure transport over long distances. Because of this, the proximity of the sea drew Southeast Asians to participate in long-distance trade, but it was not only water that linked the shores to one another - seafaring people, along with traders contributed to these trade routes as well.

''The Journal of Transport History''

{{History of technology, state=collapsed

innovation

Innovation is the practical implementation of ideas that result in the introduction of new goods or services or improvement in offering goods or services. ISO TC 279 in the standard ISO 56000:2020 defines innovation as "a new or changed entit ...

. Advances in technology

Technology is the application of knowledge to reach practical goals in a specifiable and Reproducibility, reproducible way. The word ''technology'' may also mean the product of such an endeavor. The use of technology is widely prevalent in me ...

have allowed people to travel farther, explore more territory, and expand their influence over larger and larger areas. Even in ancient times, new tools such as foot coverings, skis, and snowshoes lengthened the distances that could be traveled. As new inventions and discoveries were applied to transport

Transport (in British English), or transportation (in American English), is the intentional movement of humans, animals, and goods from one location to another. Modes of transport include air, land ( rail and road), water, cable, pipelin ...

problems, travel time decreased while the ability to move more and larger loads increased. Innovation continues as transport researchers are working to find new ways to reduce costs and increase transport efficiency.

International trade

International trade is the exchange of capital, goods, and services across international borders or territories because there is a need or want of goods or services. (see: World economy)

In most countries, such trade represents a significant ...

was the driving motivator behind advancements in global transportation in the Pre Modern world. "...there was a single global world economy with a worldwide division of labor and multilateral trade from 1500 onward." The sale and transportation of textile

Textile is an umbrella term that includes various fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, filaments, threads, different fabric types, etc. At first, the word "textiles" only referred to woven fabrics. However, weaving is not the ...

s, silver and gold, spices, slaves, and luxury goods throughout Afro-Eurasia and later the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

would see an evolution in overland and sea trade routes and travel.

Land

Road

The first earth tracks were created by humans carrying goods and often followed

The first earth tracks were created by humans carrying goods and often followed trail

A trail, also known as a path or track, is an unpaved lane or small road usually passing through a natural area. In the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland, a path or footpath is the preferred term for a pedestrian or hiking trail. ...

s. Tracks would be naturally created at points of high traffic density. As animals were domesticated, horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million yea ...

s, oxen and donkeys became an element in track-creation. With the growth of trade, tracks were often flattened or widened to accommodate animal traffic ( hollow way or drover's road

A drovers' road, drove ''roador droveway is a route for droving livestock on foot from one place to another, such as to market or between summer and winter pasture (see transhumance). Many drovers' roads were ancient routes of unknown age; oth ...

). Later, the travois

A travois (; Canadian French, from French , a frame for restraining horses; also obsolete travoy or travoise) is a historical frame structure that was used by indigenous peoples, notably the Plains Aboriginals of North America, to drag loads ove ...

, a frame used to drag loads, was developed. Animal-drawn wheeled vehicles were probably developed in the ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was the home of early civilizations within a region roughly corresponding to the modern Middle East: Mesopotamia (modern Iraq, southeast Turkey, southwest Iran and northeastern Syria), ancient Egypt, ancient Iran ( Elam, ...

in the 4th or 5th millennium BC and spread to Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

and India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

in the 4th millennium BC and China in about 1200 BC. The Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

had a significant need for good roads to extend and maintain their empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

and developed Roman roads

Roman roads ( la, viae Romanae ; singular: ; meaning "Roman way") were physical infrastructure vital to the maintenance and development of the Roman state, and were built from about 300 BC through the expansion and consolidation of the Roman Re ...

.

In the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

, John Loudon McAdam

John Loudon McAdam (23 September 1756 – 26 November 1836) was a Scottish civil engineer and road-builder. He invented a new process, " macadamisation", for building roads with a smooth hard surface, using controlled materials of ...

(1756–1836) designed the first modern highways, using inexpensive paving material of soil and stone aggregate ( macadam), and the embanked roads a few feet higher than the surrounding terrain to cause water to drain away from the surface.

With the development of motor transport

Motor transport (MT) refers to the operation and maintenance of a military vehicle fleet (especially trucks), and sometimes to the servicemembers to operate and maintain them. Traditionally, motor transport organizations are responsible for a unit ...

, starting in 1886 in Germany and in the U.S. in 1908 with the production of Ford's first Model T, there was an increased need for hard-topped roads to reduce washaway

A washaway is a particular kind of landslide that can affect man-made structures such as cuttings, embankments and bridges. They are thus a hazard to railways and road traffic.

Overview

The biggest danger with washaways is that they may be ...

s, bogging and dust on both urban and rural roads, originally using cobblestones and wooden paving in major western cities and in the early 20th century tar-bound macadam ( tarmac) and concrete paving. In 1902, Nottingham

Nottingham ( , locally ) is a city and unitary authority area in Nottinghamshire, East Midlands, England. It is located north-west of London, south-east of Sheffield and north-east of Birmingham. Nottingham has links to the legend of Robi ...

's Radcliffe Road became the first tarmac road in the world.

Rail

The history of rail transportation dates back nearly 500 years and includes systems with man or horsepower and

The history of rail transportation dates back nearly 500 years and includes systems with man or horsepower and rails

Rail or rails may refer to:

Rail transport

*Rail transport and related matters

*Rail (rail transport) or railway lines, the running surface of a railway

Arts and media Film

* ''Rails'' (film), a 1929 Italian film by Mario Camerini

* ''Rail'' ( ...

of wood (or occasionally stone). This was usually for moving coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when ...

from the mine down to a river, from where it could continue by boat, with a flanged wheel running on a rail. The use of cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron– carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impur ...

plates as rails began in the 1760s, and was followed by systems (plateway

A plateway is an early kind of railway, tramway or wagonway, where the rails are made from cast iron. They were mainly used for about 50 years up to 1830, though some continued later.

Plateways consisted of "L"-shaped rails, where the flange ...

s) where the flange was part of the rail. However, with the introduction of rolled wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.08%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4%). It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which give it a wood-like "grain" ...

rails, these became obsolete.

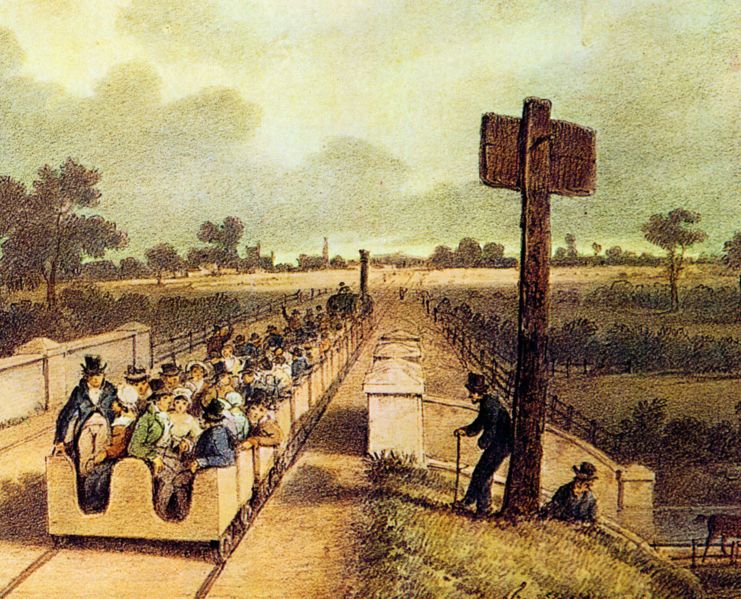

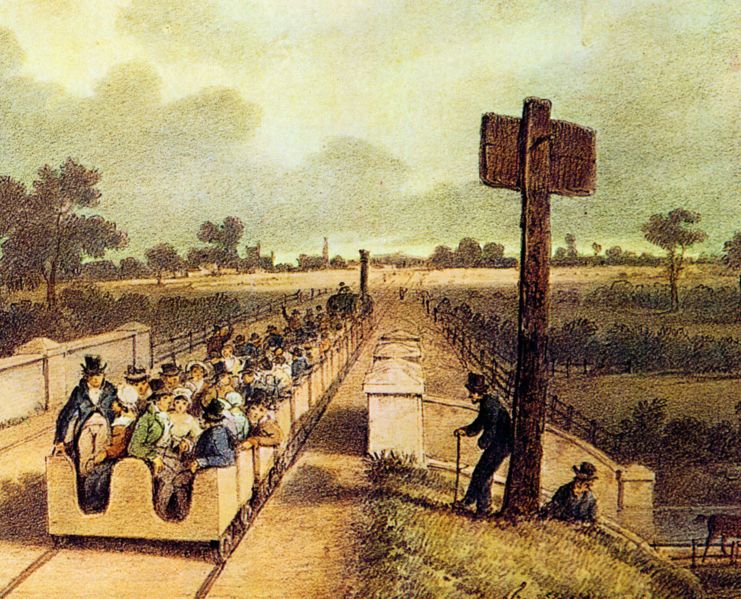

The first passenger-carrying public railway was opened by the Swansea and Mumbles Railway at Oyster mouth in 1807, using horse-drawn carriages on existing tramlines. In 1802, Richard Trevithick designed and built the first (unnamed) steam locomotive to run on smooth rails. He was a Cornish engineer and showed off his railway invention in the Welsh mining town of Merthyr Tydfil.

Before actual making the breakthrough for the first railway engine, Trevithick had been facing failures and successes along the route. One of his first successful demonstrations was the "Puffing Devil" steam powered locomotive in 1802 whereas a disaster in Greenwich in 1803 almost sealed the fate of locomotive travel, when four men were killed by an explosion of one of Trevithick's engines. This incident was used as a leverage by his rivals to stop the production of the high-pressure steam engines.

However, Trevithick's "Penydarren locomotive", marked its place in history by becoming the first full scale working railway steam locomotive. A bet between Trevithick's benefactor Samuel Homfray and Richard Crawshay prompted the key demonstration of the locomotive. Homfray had placed a wager of 500 guineas that the locomotive will transport ten tonnes of iron from the Pendydarren Ironworks to the village of Abercynon which was nearly ten miles away.

Trevithick's locomotive completed the journey in just over four hours, ultimately proving the locomotives sturdiness and reliability. However, Trevithick never got the credit he deserved and died a destitute in 1833.

Modern locomotive

Modern rail transport systems first appeared inEngland

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

in the 1820s.

Matthew Murray proved the viability of the steam engine in 1812. Salamanca was the first locomotive to incorporate two cylinders.

George Stephenson who went on to become known as the father of railways is said to have built 16 experimental locomotives for use from the year 1814–1826, the last train which he introduced known as the Killingworth Billy ran until 1881. The first intercity railway between Liverpool and Manchester was built by Stephenson in 1830. These systems, which made use of the steam locomotive, were the first practical form of mechanized land transport, and they remained the primary form of mechanized land transport for the next 100 years. The first railroad built in Great Britain was the Stockton and Darlington, which opened in 1825. It used a steam locomotive built by George Stephenson and was practical only for hauling minerals. The Liverpool and Manchester Railway, which opened in 1830, was the first modern railroad. It was a public carrier of both passengers and freight. By 1870, Britain had about 13,500 miles (21,700 km) of railroad.

In 1879, electric locomotive development was booming in Germany. In the late 19th century, Werner von Siemens demonstrated the first experimental electric passenger train. The train transported around 90,000 people and worked on the concept of insulated third rail to supply electricity. In 1881, Siemens built the world's first electric tram line in the Berlin suburb of Lichterfelde. Following this trend, many such initiatives were set up in Brighton and Vienna in 1883.

= Diesel locomotives

= A new type of railway locomotives was developed by Dr. Rudolf Diesel, which involved a new internal combustion method to propel the railway. In 1892, he proposed this method and soon sparked speculation on whether this type of engine would actually work. From the late 19th century to the early 20th century, Rudolf Diesel worked on putting diesel on track and tried to improve the power-to-weight ratio. He worked at a Swiss engineering firm Sulzer. Eventually, by the end of the Second World War, steam engines became obsolete and were rarely used in developed countries. At the system's greatest extent, in 1914, there were about 20,000 miles (32,000 km) of the track, run by 120 competing companies. The British government combined all these companies into four main groups in 1923 as an economic measure. British Railways, by name British Rail, the former national railway system of Great Britain, was created by the Transport Act of 1947, which inaugurated public ownership of the railways. The history of rail transport also includes the history of rapid transit and arguablyhistory of monorail The term monorail or industrial monorail is used to describe any number of transport systems in which a chair or carrier is suspended from, or rides on, an overhead rail structure. Unlike the well-known duo-rail system, there are many rail-guided t ...

.

Water

In the Stone Age, primitive boats developed to permit navigation of rivers and for fishing in rivers and off the coast. It has been argued that boats suitable for a significant sea crossing were necessary for people to reach Australia an estimated 40,000-45,000 years ago. With the development of

In the Stone Age, primitive boats developed to permit navigation of rivers and for fishing in rivers and off the coast. It has been argued that boats suitable for a significant sea crossing were necessary for people to reach Australia an estimated 40,000-45,000 years ago. With the development of civilization

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

...

, vessels evolved for expansion and generally grew in size for trade and war. In the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

, galleys were developed about 3000 BCPolynesian double-hulled sailing vessels

with advanced rigging were used between 1,300 BC and 900 BC by the Polynesian progeny of the

Lapita culture

The Lapita culture is the name given to a Neolithic Austronesian people and their material culture, who settled Island Melanesia via a seaborne migration at around 1600 to 500 BCE. They are believed to have originated from the northern Philipp ...

to expand 6,000 km across open ocean from the Bismarck Archipelago east to Micronesia and, eventually Hawaii. Galleys were eventually rendered obsolete by ocean-going sailing ship

A sailing ship is a sea-going vessel that uses sails mounted on masts to harness the power of wind and propel the vessel. There is a variety of sail plans that propel sailing ships, employing square-rigged or fore-and-aft sails. Some ships ...

s, such as the Arabic caravel

The caravel (Portuguese: , ) is a small maneuverable sailing ship used in the 15th century by the Portuguese to explore along the West African coast and into the Atlantic Ocean. The lateen sails gave it speed and the capacity for sailing win ...

in the 13th century, the Chinese treasure ship in the early 15th century, and the Mediterranean man-of-war in the late 15th century.

In the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

, the first steamboats and later diesel

Diesel may refer to:

* Diesel engine, an internal combustion engine where ignition is caused by compression

* Diesel fuel, a liquid fuel used in diesel engines

* Diesel locomotive, a railway locomotive in which the prime mover is a diesel engin ...

-powered ships were developed. Eventually submarines were developed mainly for military purposes for people's general benefit.

Meanwhile, specialized craft were developed for river and canal transport. Canal

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface flo ...

s were developed in Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

BC. The Indus Valley civilization in Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 243 million people, and has the world's second-lar ...

and North India

North India is a loosely defined region consisting of the northern part of India. The dominant geographical features of North India are the Indo-Gangetic Plain and the Himalayas, which demarcate the region from the Tibetan Plateau and Central ...

(from c.2600BC) had the first canal irrigation

Irrigation (also referred to as watering) is the practice of applying controlled amounts of water to land to help grow crops, landscape plants, and lawns. Irrigation has been a key aspect of agriculture for over 5,000 years and has been devel ...

system in the world. China's canal system

The history of canals in China connecting its major rivers and centers of agriculture and population extends from the legendary exploits of Yu the Great in his attempts control the flooding of the Yellow River to the present infrastructure proje ...

, whose greatest accomplishment was the Sui Dynasty's 7th-century Grand Canal between Hangzhou

Hangzhou ( or , ; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), also romanized as Hangchow, is the capital and most populous city of Zhejiang, China. It is located in the northwestern part of the province, sitting at the head of Hangzhou Bay, whic ...

and Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

, was an essential aspect of its civilization, used for irrigation, flood control

Flood control methods are used to reduce or prevent the detrimental effects of flood waters."Flood Control", MSN Encarta, 2008 (see below: Further reading). Flood relief methods are used to reduce the effects of flood waters or high water level ...

, taxation

A tax is a compulsory financial charge or some other type of levy imposed on a taxpayer (an individual or legal entity) by a governmental organization in order to fund government spending and various public expenditures (regional, local, o ...

, commercial and military transport

Military supply-chain management is a cross-functional approach to procuring, producing and delivering products and services for military materiel applications. Military supply chain management includes sub-suppliers, suppliers, internal info ...

, and colonization of new lands from the Zhou Dynasty

The Zhou dynasty ( ; Old Chinese ( B&S): *''tiw'') was a royal dynasty of China that followed the Shang dynasty. Having lasted 789 years, the Zhou dynasty was the longest dynastic regime in Chinese history. The military control of China by ...

until the end of the imperial era. Canals were developed in the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

in Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isla ...

and the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

. Ramps for water were made in 1459. Pierre-Paul Riquet

Stele in Toulouse Cathedral

Pierre-Paul Riquet, Baron de Bonrepos (29 June 1609 (some sources say 1604) – 4 October 1680) was the engineer and canal-builder responsible for the construction of the Canal du Midi.

Background

Paul Riquet was b ...

began to organise the construction of the 240 km-long Canal du Midi in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

in 1665 and it was opened in 1681. In the Industrial Revolution, inland canals were built in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

and later the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

before the development of railway

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a pre ...

s. Specialized craft were also developed for fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch fish. Fish are often caught as wildlife from the natural environment, but may also be caught from stocked bodies of water such as ponds, canals, park wetlands and reservoirs. Fishing techniques inclu ...

and later whaling

Whaling is the process of hunting of whales for their usable products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that became increasingly important in the Industrial Revolution.

It was practiced as an organized industr ...

.

Maritime history also deals with the development of navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navigation, ...

, oceanography, cartography

Cartography (; from grc, χάρτης , "papyrus, sheet of paper, map"; and , "write") is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an i ...

, and hydrography

Hydrography is the branch of applied sciences which deals with the measurement and description of the physical features of oceans, seas, coastal areas, lakes and rivers, as well as with the prediction of their change over time, for the primar ...

.

Trade

Often cities as well as their surrounding agricultural areas are typically are not self-sufficient for agriculture. Because of this, people living in these regions had forced to trade with either other cities, nomads, or other pastoralists. People would usually trade one another for things like raw materials, (such as metals like tin, bronze, copper, or iron ore) or animals.Marks, Robert. ''The Origins of the Modern World: Fate and Fortune in the Rise of the West''. Rev. and updated ed. World Social Change. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007. An "intercontinental model" of world trade, "between 1500 and 1800 on the basis of interregional competition in production and trade"Frank, Andre Gunder. ''ReOrient Global Economy in the Asian Age''. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.Ports and inland

Maritime traders most often congregated in ports, which were considered the point in which land and sea met that linked the hinterland to the wider world. There were some ports that were more favored than others, blessed with a good location, with sufficient warehouse facilities, accessible harbors, and adequate supplies of food and water became "entrepôts," which were essentially the super-centers for trade. It was rare that these ports were ever considered a final destination, though, but rather central meeting points in what was an ever-changing economic and political environment. Whether in Asia, Europe, or Africa, these port centers consisted of ethnically and culturally diverse communities. Many had officials that were of foreign birth or ancestry - they were skilled in being knowledgeable of the various cultures and languages of merchants that would work throughout the ports who were also foreign, this was done in order to be successful in supervising the trade that had occurred. Throughout many of the ports, merchants had become a more powerful group in local politics. Further, these ports promoted cultural exchange, along with economic exchange, due to the fact that it had been open to the world for races, cultures, and ideas to intermix with one another, along with the fact that this blend of both locals and outsiders from diverse backgrounds that were open to accepting cultural differences. Nation-building and modernity reduced the role of trade through the sea and increased the reliance on trade through the land and the air in economic and social exchange. Even though Singapore, Bangkok, and Hong Kong are still vibrant and available to the world, similar to their early modern counterparts serving functions such as tourism which is unrelated to foreign trade, only a few ports are as economically crucial today as they had been in the past. Inland trade moved both by water, and overland itself. For example, shipping in small boats went along the coasts of India, but inland waterways were readily available to use to transport goods throughout many parts of India, especially in the south. Caravans that contained numbers from ten, all the way to up forty thousand pack or draft animals moved overland at a time. Combinations of these forms of transportation carried throughout the subcontinent and were therefore transshipped to and from long-distance maritime trade. The majority of all of the port cities were in symbiosis with the caravan routes to and from their related hinterland interiors, and sometimes even with distant transcontinental regions. This is especially true in Central Asia - and it is suggested that the continental trade over both the land and the ocean maritime trade should be viewed not as separate or competitive, but rather as mirror images of one another.Air

Humanity's desire to fly likely dates to the first time man observed birds, an observation illustrated in the legendary stories ofDaedalus

In Greek mythology, Daedalus (, ; Greek: Δαίδαλος; Latin: ''Daedalus''; Etruscan: ''Taitale'') was a skillful architect and craftsman, seen as a symbol of wisdom, knowledge and power. He is the father of Icarus, the uncle of Perdix, a ...

and Icarus in Greek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities ...

, and the Vimana

Vimāna are mythological flying palaces or chariots described in Hindu texts and Sanskrit epics. The "Pushpaka Vimana" of Ravana (who took it from Kubera; Rama returned it to Kubera) is the most quoted example of a vimana. Vimanas are also men ...

s in Indian mythology. Much of the focus of early research was on imitating birds, but through trial and error

Trial and error is a fundamental method of problem-solving characterized by repeated, varied attempts which are continued until success, or until the practicer stops trying.

According to W.H. Thorpe, the term was devised by C. Lloyd Morgan (18 ...

, balloons, airship

An airship or dirigible balloon is a type of aerostat or lighter-than-air aircraft that can navigate through the air under its own power. Aerostats gain their lift from a lifting gas that is less dense than the surrounding air.

In early ...

s, glider

Glider may refer to:

Aircraft and transport Aircraft

* Glider (aircraft), heavier-than-air aircraft primarily intended for unpowered flight

** Glider (sailplane), a rigid-winged glider aircraft with an undercarriage, used in the sport of glidin ...

s and eventually powered aircraft

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to fly by gaining support from the air. It counters the force of gravity by using either static lift or by using the dynamic lift of an airfoil, or in a few cases the downward thrust from jet engine ...

and other types of flying machines were invented.

Kites were the first form of man-made flying objects, and early records suggest that kites were around before 200 BC in China. Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially res ...

's dream of flight found expression in several designs, but he did not attempt to demonstrate flight by literally constructing them.

During the 17th and 18th century, when scientists began analysing the Earth's atmosphere, gases such as hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic ...

were discovered which in turn led to the invention of hydrogen balloons. Various theories in mechanics

Mechanics (from Ancient Greek: μηχανική, ''mēkhanikḗ'', "of machines") is the area of mathematics and physics concerned with the relationships between force, matter, and motion among physical objects. Forces applied to object ...

by physicists during the same period of time—notably fluid dynamics and Newton's laws of motion

Newton's laws of motion are three basic laws of classical mechanics that describe the relationship between the motion of an object and the forces acting on it. These laws can be paraphrased as follows:

# A body remains at rest, or in moti ...

—led to the foundation of modern aerodynamics

Aerodynamics, from grc, ἀήρ ''aero'' (air) + grc, δυναμική (dynamics), is the study of the motion of air, particularly when affected by a solid object, such as an airplane wing. It involves topics covered in the field of fluid dy ...

. Tethered balloons filled with hot air were used in the first half of the 19th century and saw considerable action in several mid-century wars, most notably the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, where balloons provided observation during the Siege of Petersburg

The Richmond–Petersburg campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War. Although it is more popularly known as the Siege of Petersburg, it was not a cla ...

.

Apart from some scattered reference in ancient and medieval records, resting on slender evidence and in need of interpretation, the earliest clearly verifiable human flight took place in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

in 1783, when Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier

Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier () was a French chemistry and physics teacher, and one of the first pioneers of aviation. He made the first manned free balloon flight with François Laurent d'Arlandes on 21 November 1783, in a Montgolfier bal ...

and François Laurent d'Arlandes went in a hot air balloon

A hot air balloon is a lighter-than-air aircraft consisting of a bag, called an envelope, which contains heated air. Suspended beneath is a gondola or wicker basket (in some long-distance or high-altitude balloons, a capsule), which carries ...

invented by the Montgolfier brothers

The Montgolfier brothers – Joseph-Michel Montgolfier (; 26 August 1740 – 26 June 1810) and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier (; 6 January 1745 – 2 August 1799) – were aviation pioneers, balloonists and paper manufacturers from the commune A ...

. The Wright brothers made the first sustained, controlled and powered heavier-than-air flight on 17 December 1903, in their revolutionary aircraft, the Wright Flyer

The ''Wright Flyer'' (also known as the ''Kitty Hawk'', ''Flyer'' I or the 1903 ''Flyer'') made the first sustained flight by a manned heavier-than-air powered and controlled aircraft—an airplane—on December 17, 1903. Invented and flown b ...

.

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

saw a drastic increase in the pace of aircraft development and production. All countries involved in the war stepped up development and production of aircraft and flight-based weapon delivery systems, such as the first long-range bomber.

After the war ended, commercial aviation grew rapidly, using mostly ex-military aircraft to transport people and cargo. This growth was accelerated by the glut of heavy and super-heavy bomber airframes like the Lancaster that could be converted into commercial aircraft. The first commercial jet airliner to fly was the British De Havilland Comet. This marked the beginning of the Jet Age

The Jet Age is a period in the history of aviation defined by the advent of aircraft powered by jet turbine engines, and by the social change this brought about.

Jet airliners were able to fly much higher, faster, and farther than older pisto ...

, a period of relatively cheap and fast international travel.

In the beginning of the 21st century, subsonic military aviation focused on eliminating the pilot in favor of remotely operated or completely autonomous vehicles. Several unmanned aerial vehicles or UAVs have been developed. In April 2001, the unmanned aircraft Global Hawk

The Northrop Grumman RQ-4 Global Hawk is a high-altitude, remotely-piloted surveillance aircraft of the 1990s–2020s. It was initially designed by Ryan Aeronautical (now part of Northrop Grumman), and known as Tier II+ during development. T ...

flew from Edwards AFB in the US to Australia non-stop and unrefueled. This is the longest point-to-point flight ever undertaken by an unmanned aircraft, and took 23 hours and 23 minutes. In October 2003, the first totally autonomous flight across the Atlantic by a computer-controlled model aircraft occurred. Major disruptions to air travel in the 21st century included the closing of U.S. airspace following the September 11 attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commer ...

, the closing of northern European airspace after the 2010 eruptions of Eyjafjallajökull

Between March and June 2010 a series of volcanic events at Eyjafjallajökull in Iceland caused enormous disruption to air travel across Western Europe.

The disruptions started over an initial period of six days in April 2010. Additional locali ...

, and the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic, also known as the coronavirus pandemic, is an ongoing global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The novel virus was first identi ...

.

Space

The realistic dream of spaceflight dated back toKonstantin Tsiolkovsky

Konstantin Eduardovich Tsiolkovsky (russian: Константи́н Эдуа́рдович Циолко́вский , , p=kənstɐnʲˈtʲin ɪdʊˈardəvʲɪtɕ tsɨɐlˈkofskʲɪj , a=Ru-Konstantin Tsiolkovsky.oga; – 19 September 1935) ...

, however Tsiolkovsky wrote in Russian, and this was not widely influential outside Russia. Spaceflight became an engineering possibility with the work of Robert H. Goddard

Robert Hutchings Goddard (October 5, 1882 – August 10, 1945) was an American engineer, professor, physicist, and inventor who is credited with creating and building the world's first liquid-fueled rocket. Goddard successfully laun ...

's publication in 1919 of his paper ' Robert H. Goddard#A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes ,A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes'; where his application of the de Laval nozzle

A de Laval nozzle (or convergent-divergent nozzle, CD nozzle or con-di nozzle) is a tube which is pinched in the middle, making a carefully balanced, asymmetric hourglass shape. It is used to accelerate a compressible fluid to supersonic speeds ...

to liquid-propellant rockets gave sufficient power that interplanetary travel became possible. This paper was highly influential on Hermann Oberth and Wernher von Braun

Wernher Magnus Maximilian Freiherr von Braun ( , ; 23 March 191216 June 1977) was a German and American aerospace engineer and space architect. He was a member of the Nazi Party and Allgemeine SS, as well as the leading figure in the develop ...

, later key players in spaceflight.

The first human spaceflight was achieved with the Soviet space program

The Soviet space program (russian: Космическая программа СССР, Kosmicheskaya programma SSSR) was the national space program of the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), active from 1955 until the dissoluti ...

's Vostok 1

Vostok 1 (russian: link=no, Восток, ''East'' or ''Orient'' 1) was the first spaceflight of the Vostok programme and the first human orbital spaceflight in history. The Vostok 3KA space capsule was launched from Baikonur Cosmodrome on Apr ...

mission in 1961. The lead architects behind the mission were Sergei Korolev

Sergei Pavlovich Korolev (russian: Сергей Павлович Королёв, Sergey Pavlovich Korolyov, sʲɪrˈɡʲej ˈpavləvʲɪtɕ kərɐˈlʲɵf, Ru-Sergei Pavlovich Korolev.ogg; ukr, Сергій Павлович Корольов, ...

and Kerim Kerimov

Lieutenant General Kerim Abbasali oghlu Kerimov ( az, Kərim Abbasəli oğlu Kərimov, russian: Керим Аббас-Алиевич Керимов; November 14, 1917March 29, 2003) was a Soviet and Russian engineer of Azerbaijani ethnicity and ...

, with Yuri Gagarin

Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin; Gagarin's first name is sometimes transliterated as ''Yuriy'', ''Youri'', or ''Yury''. (9 March 1934 – 27 March 1968) was a Soviet pilot and cosmonaut who became the first human to journey into outer space. T ...

being the first astronaut. On May 5, 1961, the US launched its first suborbital Mercury astronaut, Alan Shepard

Alan Bartlett Shepard Jr. (November 18, 1923 – July 21, 1998) was an American astronaut, naval aviator, test pilot, and businessman. In 1961, he became the second person and the first American to travel into space and, in 1971, he beca ...

, in the ''Freedom 7

Mercury-Redstone 3, or ''Freedom 7'', was the first United States human spaceflight, on May 5, 1961, piloted by astronaut Alan Shepard. It was the first crewed flight of Project Mercury. The project had the ultimate objective of putting an astr ...

'' capsule. Unlike Gagarin, Shepard manually controlled his spacecraft's attitude and landed inside it hence making his mission the first "completed" human spaceflight according to previous FAI definitions. Kerimov later went on to launch the first space dock

A space dock is a hypothesised type of space station that is able to repair or build spacecraft similar to maritime shipyards on Earth. They remove the need for new spacecraft to perform a space launch to reach space and existing spacecraft ...

s (Kosmos 186 and Kosmos 188

Kosmos 186 (russian: Космос-186 meaning ''Cosmos 186'') and Kosmos 188 (russian: Космос-188 meaning ''Cosmos 188'') were two uncrewed Soviet Union spacecraft that incorporated a Soyuz programme descent module for landing scientific ...

) in 1967 and the first space stations (Salyut

The ''Salyut'' programme (russian: Салют, , meaning "salute" or "fireworks") was the first space station programme, undertaken by the Soviet Union. It involved a series of four crewed scientific research space stations and two crewed ...

and Mir

''Mir'' (russian: Мир, ; ) was a space station that operated in low Earth orbit from 1986 to 2001, operated by the Soviet Union and later by Russia. ''Mir'' was the first modular space station and was assembled in orbit from 1986 to&n ...

series) from 1971 to 1991. The first spaceflight to the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

was achieved with NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil List of government space agencies, space program ...

's Apollo 11

Apollo 11 (July 16–24, 1969) was the American spaceflight that first landed humans on the Moon. Commander Neil Armstrong and lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin landed the Apollo Lunar Module ''Eagle'' on July 20, 1969, at 20:17 UTC, ...

mission in 1969, with Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin

Buzz Aldrin (; born Edwin Eugene Aldrin Jr.; January 20, 1930) is an American former astronaut, engineer and fighter pilot. He made three spacewalks as pilot of the 1966 Gemini 12 mission. As the Lunar Module ''Eagle'' pilot on the 1969 A ...

being the first astronauts on the Moon.

Navigational advances

The thirteenth century saw the rise of the magnetic compass for overseas travel. Prior to its creation, seamen would have to rely on landmarks and stars as guides for navigation. The compass allowed sailors to plot a course, and using magnetic north as a reference, could travel through fog and overcast. This also led to shorter voyages, as they could plot more linear approaches to destinations.Portolan chart

Portolan charts are nautical charts, first made in the 13th century in the Mediterranean basin and later expanded to include other regions. The word ''portolan'' comes from the Italian ''portulano'', meaning "related to ports or harbors", and wh ...

s rose up, plotting this linear excursion routes, making sea navigation more accurate and efficient. In 1761, marine chronometer

A marine chronometer is a precision timepiece that is carried on a ship and employed in the determination of the ship's position by celestial navigation. It is used to determine longitude by comparing Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), or in the modern ...

was invented.

See also

* History of public transport * Medieval transport *Timeline of artificial satellites and space probes

This Timeline of artificial satellites and Space probe

A space probe is an artificial satellite that travels through space to collect scientific data. A space probe may orbit Earth; approach the Moon; travel through interplanetary space; fl ...

* Timeline of aviation

A timeline is a display of a list of events in chronological order. It is typically a graphic design showing a long bar labelled with dates paralleling it, and usually contemporaneous events.

Timelines can use any suitable scale representi ...

* Timeline of diving technology

* Timeline of jet power

* Timeline of transportation technology

This is a timeline of transportation technology and technological developments in the culture of transportation.

Antiquity

*20th millennium BC – rafts used on rivers.

*7th millennium BC– Earliest known shoes.

*6th millennium BC– Dugou ...

References

Further reading

*Casson, Lionel. 1984. ''Ancient Trade and Society.'' Detroit: Wayne State University Press. * Creveld van, Martin, 1977. ''Supplying War: Logistics from Wallenstein to Patton.'' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. * Duc, Gérard; Perroux, Olivier; Schiedt, Hans-Ulrich; Walter, François (Ed.). 2014. ''Transport and mobility history. Between modal competition and coordination (1918 in our days).'' Neuchâtel: Editions Alphil. () *Farooque, Abdul K.M. 1977. ''Roads and Communications in Mughal India.'' Delhi: Idarah-I Adabiyat-I Delli.External links

''The Journal of Transport History''

{{History of technology, state=collapsed

Transport

Transport (in British English), or transportation (in American English), is the intentional movement of humans, animals, and goods from one location to another. Modes of transport include air, land ( rail and road), water, cable, pipelin ...

Transport

Transport (in British English), or transportation (in American English), is the intentional movement of humans, animals, and goods from one location to another. Modes of transport include air, land ( rail and road), water, cable, pipelin ...