Transglobe Expedition on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Transglobe Expedition (1979–1982) was the first expedition to make a longitudinal (north–south)

On 29 August 1980, Ranulph Fiennes left with Burton and Shephard for the South Pole. They travelled by snowmobiles, pulling sledges with supplies, while Kershaw flew ahead to leave fuel depots for them. As they travelled, they took 2-meter snow samples, one of many scientific undertakings that convinced sponsors to support the trip. They reached the South Pole on 15 December 1980. They remained in a small camp next to the South Pole station dome, where they played the first game of

On 29 August 1980, Ranulph Fiennes left with Burton and Shephard for the South Pole. They travelled by snowmobiles, pulling sledges with supplies, while Kershaw flew ahead to leave fuel depots for them. As they travelled, they took 2-meter snow samples, one of many scientific undertakings that convinced sponsors to support the trip. They reached the South Pole on 15 December 1980. They remained in a small camp next to the South Pole station dome, where they played the first game of

Rough map of the expedition

(based o

the official route graphic

. Red shows the rough path; cyan shows the 0- and 180-degree meridians. {{Authority control Polar exploration 1980 in Antarctica North Pole History of the Ross Dependency

circumnavigation

Circumnavigation is the complete navigation around an entire island, continent, or astronomical body (e.g. a planet or moon). This article focuses on the circumnavigation of Earth.

The first recorded circumnavigation of the Earth was the ...

of the Earth using only surface transport. British adventurer Sir Ranulph Fiennes

Sir Ranulph Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes, 3rd Baronet (born 7 March 1944), commonly known as Sir Ranulph Fiennes () and sometimes as Ran Fiennes, is a British explorer, writer and poet, who holds several endurance records.

Fiennes served in the ...

led a team, including Oliver Shepard

Oliver Shepard (born 1946) is a British explorer. He participated in the Transglobe Expedition, the first expedition to circumnavigate the globe from pole to pole.

Shepard was educated at Heatherdown School, near Ascot in Berkshire, followed by ...

and Charles R. Burton

Charles Robert Burton (13 December 1942 – 15 July 2002) known as Charlie Burton was an English explorer, best known for his part in the Transglobe Expedition, the first expedition to circumnavigate the globe from pole to pole. Serving as cook, ...

, that attempted to follow the Greenwich meridian

The historic prime meridian or Greenwich meridian is a geographical reference line that passes through the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, in London, England. The modern IERS Reference Meridian widely used today is based on the Greenwich m ...

over both land and water. They began in Greenwich

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich ...

in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

in September 1979 and travelled south, arriving at the South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole, Terrestrial South Pole or 90th Parallel South, is one of the two points where Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on Earth and lies antipod ...

on 15 December 1980. Over the next 14 months, they travelled north, reaching the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Ma ...

on 11 April 1982. Travelling south once more, they arrived again in Greenwich on 29 August 1982.''Guinness Book of World Records 1997'' It required traversing both of the poles and the use of boats in some places. Oliver Shepard

Oliver Shepard (born 1946) is a British explorer. He participated in the Transglobe Expedition, the first expedition to circumnavigate the globe from pole to pole.

Shepard was educated at Heatherdown School, near Ascot in Berkshire, followed by ...

took part in the Antarctic leg of the expedition. Ginny Fiennes

Virginia Frances, Lady Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes ( Pepper; 9 July 1947 – 20 February 2004), known as Ginny Fiennes, was an English explorer. She was the first woman to be awarded the Polar Medal, and the first woman to be voted in to join the ...

handled all communications between the land team and their support, and ran the polar bases.

Planning

The original idea for the expedition was conceived byGinny Fiennes

Virginia Frances, Lady Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes ( Pepper; 9 July 1947 – 20 February 2004), known as Ginny Fiennes, was an English explorer. She was the first woman to be awarded the Polar Medal, and the first woman to be voted in to join the ...

in February 1972. The trip was entirely funded through sponsorships and the free labour of the expedition members, which took seven years to organize.

Before the expedition, they had to limit the food that they ate. They brought much bread, cereal, and coffee. During their crossing of the Sahara

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

, they brought no butter because of high temperatures. They also had to put repellent cream and anti-malarial tablets on themselves in order to keep insects away.

Expedition

South Pole

Ranulph Fiennes, Charles Burton, and Oliver Shepard left London on 2 September 1979, beginning with a relatively simple overland trip through France and Spain, then across West Africa through theSahara

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

. They boarded the ship the ''Benjamin Bowring'' in the Gulf of Guinea

The Gulf of Guinea is the northeasternmost part of the tropical Atlantic Ocean from Cape Lopez in Gabon, north and west to Cape Palmas in Liberia. The intersection of the Equator and Prime Meridian (zero degrees latitude and longitude) is i ...

and travelled by sea to South Africa. After preparations in South Africa, they sailed for Antarctica on 22 December 1979, and arrived on 4 January 1980.

With help from Ginny Fiennes and Giles Kershaw, they built a base camp near the SANAE

SANAE is the South African National Antarctic Expedition. The name refers both to the overwintering bases (numbered in Roman numerals, e.g. SANAE IV), and the team spending the winter (numbered in Arabic numerals, e.g. SANAE 47). The current ba ...

III base. They named the base camp Ryvingen, after the nearby Ryvingen Peak. Burton, Shepard, Ranulph Fiennes, and Ginny Fiennes (and their dog Bothie) remained at this base all winter, in four cardboard huts which quickly became buried in the snow.

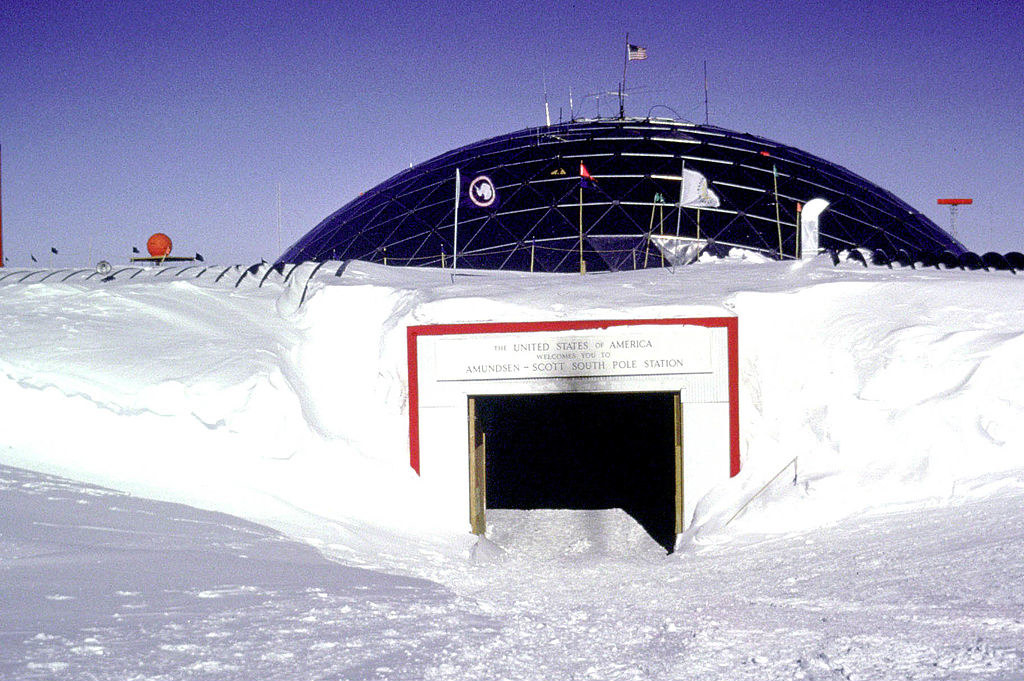

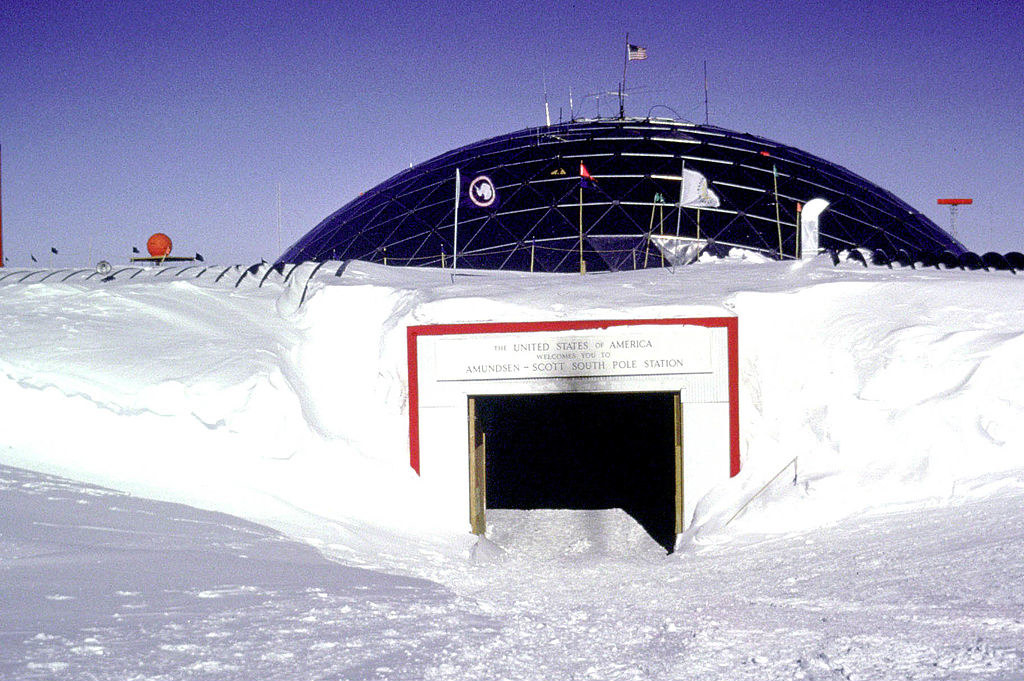

On 29 August 1980, Ranulph Fiennes left with Burton and Shephard for the South Pole. They travelled by snowmobiles, pulling sledges with supplies, while Kershaw flew ahead to leave fuel depots for them. As they travelled, they took 2-meter snow samples, one of many scientific undertakings that convinced sponsors to support the trip. They reached the South Pole on 15 December 1980. They remained in a small camp next to the South Pole station dome, where they played the first game of

On 29 August 1980, Ranulph Fiennes left with Burton and Shephard for the South Pole. They travelled by snowmobiles, pulling sledges with supplies, while Kershaw flew ahead to leave fuel depots for them. As they travelled, they took 2-meter snow samples, one of many scientific undertakings that convinced sponsors to support the trip. They reached the South Pole on 15 December 1980. They remained in a small camp next to the South Pole station dome, where they played the first game of cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by st ...

at the South Pole, and departed on 23 December 1980. They descended the Scott Glacier (the third party to do so), crossed the Ross Ice Shelf

The Ross Ice Shelf is the largest ice shelf of Antarctica (, an area of roughly and about across: about the size of France). It is several hundred metres thick. The nearly vertical ice front to the open sea is more than long, and between h ...

, and arrived at Scott Base

Scott Base is a New Zealand Antarctic research station at Pram Point on Ross Island near Mount Erebus in New Zealand's Ross Dependency territorial claim. It was named in honour of Captain Robert Falcon Scott, RN, leader of two British expedit ...

on 11 January 1981, completing their Antarctic crossing.

North Pole

As part of the expedition, Fiennes and Burton completed theNorthwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the ...

. They left Tuktoyaktuk

Tuktoyaktuk , or ''Tuktuyaaqtuuq'' (Inuvialuktun: ''it looks like a caribou''), is an Inuvialuit hamlet located in the Inuvik Region of the Northwest Territories, Canada, at the northern terminus of the Inuvik–Tuktoyaktuk Highway.Montgomer ...

on 26 July 1981, in a 18 ft open Boston Whaler

Boston Whaler is an American boat manufacturer. It is a subsidiary of the Brunswick Boat Group, a division of the Brunswick Corporation. Boston Whalers were originally produced in Massachusetts, hence the name, but today are manufactured in Edg ...

made motorboat and reached Tanquary Fiord

Tanquary Fiord is a fjord on the north coast of the Arctic Archipelago's Ellesmere Island, Nunavut, Canada. It is located in the Quttinirpaaq National Park and extends in a north-westerly direction from Greely Fiord.

History

Radiocarbon da ...

, 36 days later, on 31 August 1981. Their journey was the first open boat transit of the Northwest Passage from West to East, and covered around , taking a route through Dolphin and Union Strait

Dolphin and Union Strait lies in both the Northwest Territories ( Inuvik Region) and Nunavut ( Kitikmeot Region), Canada, between the mainland and Victoria Island. It is part of the Northwest Passage. It links Amundsen Gulf, lying to the northwe ...

following the South coast of Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

and King William Islands, North, via Franklin Strait

The Franklin Strait is an Arctic waterway in Northern Canada's territory of Nunavut

Nunavut ( , ; iu, ᓄᓇᕗᑦ , ; ) is the largest and northernmost territory of Canada. It was separated officially from the Northwest Territories ...

and Peel Sound

Peel Sound is an Arctic waterway in the Qikiqtaaluk, Nunavut, Canada. It separates Somerset Island on the east from Prince of Wales Island on the west. To the north it opens onto Parry Channel while its southern end merges with Franklin Strai ...

, to Resolute Bay

Resolute Bay is an Arctic waterway in the Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut, Canada. It is located in Parry Channel on the southern side of Cornwallis Island. The hamlet of Resolute is located on the northern shore of the bay with Resolute Bay Airpo ...

(on the southern side of Cornwallis Island), around the South and East coasts of Devon Island

Devon Island ( iu, ᑕᓪᓗᕈᑎᑦ, ) is an island in Canada and the largest uninhabited island (no permanent residents) in the world. It is located in Baffin Bay, Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut, Canada. It is one of the largest members of the ...

, through Hell Gate

Hell Gate is a narrow tidal strait in the East River in New York City. It separates Astoria, Queens, from Randall's and Wards Islands.

Etymology

The name "Hell Gate" is a corruption of the Dutch phrase ''Hellegat'' (it first appeared on ...

(near Cardigan Strait) and across Norwegian Bay to Eureka

Eureka (often abbreviated as E!, or Σ!) is an intergovernmental organisation for research and development funding and coordination. Eureka is an open platform for international cooperation in innovation. Organisations and companies applying th ...

, Greely Bay and the head of Tanquary Fiord

Tanquary Fiord is a fjord on the north coast of the Arctic Archipelago's Ellesmere Island, Nunavut, Canada. It is located in the Quttinirpaaq National Park and extends in a north-westerly direction from Greely Fiord.

History

Radiocarbon da ...

.

Between Tuktoyaktuk and Tanquary Fiord, they traveled at an average speed of around per day.

Once they reached Tanquary Fiord they had to trek overland, via Lake Hazen

Lake Hazen is a freshwater lake in the northern part of Ellesmere Island, Nunavut, Canada, north of the Arctic Circle.

It is the largest lake north of the Arctic Circle by volume. By surface area it is third largest, after Lake Taymyr in Russia ...

, to Alert, before setting up their winter base camp.

Impact

The journey was recorded in a book by Fiennes, ''To the Ends of the Earth: The Transglobe Expedition, The First Pole-to-Pole Circumnavigation of the Globe'' (1983). It was also the subject of a 1983 film, also titled ''To the Ends of the Earth'', made by director William Kronick and featuring actorRichard Burton

Richard Burton (; born Richard Walter Jenkins Jr.; 10 November 1925 – 5 August 1984) was a Welsh actor. Noted for his baritone voice, Burton established himself as a formidable Shakespearean actor in the 1950s, and he gave a memorable pe ...

as the narrator.

The trip is recorded in the 1997 ''Guinness Book of World Records

''Guinness World Records'', known from its inception in 1955 until 1999 as ''The Guinness Book of Records'' and in previous United States editions as ''The Guinness Book of World Records'', is a reference book published annually, listing world ...

''.

Transglobe Expedition Trust

Following the expedition, in 1993 a charitable trust was established to support other expeditions with humanitarian, scientific or educational goals. The trust is a registered UK charity and has supported a number of projects including Ed Stafford's 2010 expedition to walk the length of theAmazon river

The Amazon River (, ; es, Río Amazonas, pt, Rio Amazonas) in South America is the largest river by discharge volume of water in the world, and the disputed longest river system in the world in comparison to the Nile.

The headwaters of t ...

, and survey of the endangered Bactrian camel

The Bactrian camel (''Camelus bactrianus''), also known as the Mongolian camel or domestic Bactrian camel, is a large even-toed ungulate native to the steppes of Central Asia. It has two humps on its back, in contrast to the single-humped dro ...

.

Further reading

* *See also

* ''''References

External links

*Rough map of the expedition

(based o

the official route graphic

. Red shows the rough path; cyan shows the 0- and 180-degree meridians. {{Authority control Polar exploration 1980 in Antarctica North Pole History of the Ross Dependency