Traditionalist conservatism in the United States on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Traditionalist conservatism in the United States is a

political

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that studi ...

, social philosophy

Social philosophy examines questions about the foundations of social institutions, social behavior, and interpretations of society in terms of ethical values rather than empirical relations. Social philosophers emphasize understanding the social ...

and variant of conservatism

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

based on the philosophy and writings of Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

and Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS">New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS/nowiki>_1729_–_9_July_1797)_was_an_NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">N ...

.

Traditional conservatives emphasize the bonds of social order

The term social order can be used in two senses: In the first sense, it refers to a particular system of social structures and institutions. Examples are the ancient, the feudal, and the capitalist social order. In the second sense, social order ...

over hyper-individualism, and the defense of ancestral institutions. Traditionalist conservatives believe in a transcendent moral order, manifested through certain natural laws to which they believe society ought to conform in a prudent manner. Traditionalist conservatives also emphasize the rule of law

The rule of law is the political philosophy that all citizens and institutions within a country, state, or community are accountable to the same laws, including lawmakers and leaders. The rule of law is defined in the ''Encyclopedia Britannic ...

in securing individual liberty.

Some observers have stated that traditionalist conservatism has been overshadowed or eclipsed by fiscal conservatives

Fiscal conservatism is a political and economic philosophy regarding fiscal policy and fiscal responsibility with an ideological basis in capitalism, individualism, limited government, and ''laissez-faire'' economics.M. O. Dickerson et al., ''A ...

and social conservatives (particularly the Christian right

The Christian right, or the religious right, are Christian political factions characterized by their strong support of socially conservative and traditionalist policies. Christian conservatives seek to influence politics and public policy with ...

).

History

18th century

In terms of "classical conservatism", the Federalists had no connection with European-style aristocracy, monarchy or established religion. Historian John P. Diggins has said:Thanks to the framers, American conservatism began on a genuinely lofty plane. James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, John Marshall, John Jay, James Wilson, and, above all, John Adams aspired to create a republic in which the values so precious to conservatives might flourish: harmony, stability, virtue, reverence, veneration, loyalty, self-discipline, and moderation. This was classical conservatism in its most authentic expression.Something akin to Burkean traditionalism was transported to the American colonies through the policies and principles of the

Federalist Party

The Federalist Party was a conservative political party which was the first political party in the United States. As such, under Alexander Hamilton, it dominated the national government from 1789 to 1801.

Defeated by the Jeffersonian Repu ...

and its leadership as embodied by John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

and Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charle ...

. Federalists strongly opposed the excesses and instability of the French Revolution, defended traditional Christian morality and supported a new "natural aristocracy" based on "property, education, family status, and sense of ethical responsibility".

John Adams was one of the earliest defenders of a traditional social order in Revolutionary America. In his ''Defence of the Constitution'' (1787), Adams attacked the ideas of radicals like Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

, who advocated for a unicameral legislature (Adams deemed it too democratic). His translation of ''Discourses on Davila'' (1790), which also contained his own commentary, was an examination of "human motivation in politics". Adams believed that human motivation inevitably led to dangerous impulses where the government would need to sometimes intervene.

The leader of the Federalist Party was Alexander Hamilton, Secretary of the Treasury and co-author of ''The Federalist Papers'' (1787–1788) which was then and to this day remains a major interpretation of the new 1789 Constitution. Hamilton was critical of both Jeffersonian classical liberalism and the radical ideas coming out of the French Revolution. He rejected ''laissez-faire'' economics and favored a strong central government.

19th century

In the era after the Revolutionary Generation, the Whig Party had an approach that resembled Burkean conservatism, although Whigs rarely cited Burke. Whig statesmen led the charge for tradition and custom against the prevailing democratic ethos of the Jacksonian Era. Standing for hierarchy and organic society, in many ways their concepts of the Union paralleledBenjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a central role in the creation ...

's "One Nation Conservatism".

Along with Henry Clay, the most noteworthy Whig statesman was Boston's Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison ...

. A firm Unionist, his most famous speech was his "Second Reply to Hayne" (1829) where he criticized the argument from Southerners such as John C. Calhoun

John Caldwell Calhoun (; March 18, 1782March 31, 1850) was an American statesman and political theorist from South Carolina who held many important positions including being the seventh vice president of the United States from 1825 to 1832. He ...

that the states had a right to nullify federal laws they deemed unconstitutional. Webster rarely mentioned Burke but he occasionally followed similar lines of thought.

Webster's intellectual and political heir was Rufus Choate

Rufus Choate (October 1, 1799July 13, 1859) was an American lawyer, orator, and Senator who represented Massachusetts as a member of the Whig Party. He is regarded as one of the greatest American lawyers of the 19th century, arguing over a th ...

, who admired Burke. Choate was a part of the emerging legal culture in New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

, centered on the newly formed Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (Harvard Law or HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest continuously operating law school in the United States.

Each c ...

. He believed that lawyers were preservers and conservers of the Constitution and that it was the duty of the educated to govern political institutions. Choate's most famous address was "The Position and Functions of the American Bar, as an Element of Conservatism in the State" (1845).

Two figures in the Northern antebellum period were what Emory University

Emory University is a private research university in Atlanta, Georgia. Founded in 1836 as "Emory College" by the Methodist Episcopal Church and named in honor of Methodist bishop John Emory, Emory is the second-oldest private institution of ...

professor Patrick Allitt referred to as the "Guardians of Civilization": George Ticknor

George Ticknor (August 1, 1791 – January 26, 1871) was an American academician and Hispanist, specializing in the subject areas of languages and literature. He is known for his scholarly work on the history and criticism of Spanish literature.

...

and Edward Everett

Edward Everett (April 11, 1794 – January 15, 1865) was an American politician, Unitarian pastor, educator, diplomat, and orator from Massachusetts. Everett, as a Whig, served as U.S. representative, U.S. senator, the 15th governor of Mass ...

.

George Ticknor

George Ticknor (August 1, 1791 – January 26, 1871) was an American academician and Hispanist, specializing in the subject areas of languages and literature. He is known for his scholarly work on the history and criticism of Spanish literature.

...

, a Dartmouth-educated academic at Harvard, was the chief purveyor of humane learning in the Boston area. A founder of the Boston Public Library

The Boston Public Library is a municipal public library system in Boston, Massachusetts, United States, founded in 1848. The Boston Public Library is also the Library for the Commonwealth (formerly ''library of last recourse'') of the Commonwea ...

and the scion of an old Federalist family, Ticknor educated his students in Romance languages and the works of Dante and Cervantes at home while promoting America abroad to his many international friends, including Lord Byron and Talleyrand.

Like Ticknor, Edward Everett

Edward Everett (April 11, 1794 – January 15, 1865) was an American politician, Unitarian pastor, educator, diplomat, and orator from Massachusetts. Everett, as a Whig, served as U.S. representative, U.S. senator, the 15th governor of Mass ...

was educated at the same German university (Goettigen) and advocated for the U.S. to follow same virtues as the ancient Greeks and eventually went into politics as a Whig. A firm Unionist (like his friend Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison ...

), Everett deplored the Jacksonian Democracy that swept the nation. A famed orator in his own right, he supported Lincoln against Southern secession.

American Catholic journalist and political theorist (and former political and religious radical) Orestes Brownson

Orestes Augustus Brownson (September 16, 1803 – April 17, 1876) was an American intellectual and activist, preacher, labor organizer, and noted Catholic convert and writer.

Brownson was a publicist, a career which spanned his affiliation with ...

is best known for writing ''The American Republic'', an 1865 treatise examining how America fulfills Catholic tradition and Western Civilization. Brownson was critical of both the Northern abolitionists and the Southern secessionists and was himself a solid Unionist.

20th century

In the 20th century, traditionalist conservatism on both sides of the Atlantic centered on two publications: '' The Bookman'' and its successor, '' The American Review''. Owned and edited by the eccentricSeward Collins

Seward Bishop Collins (April 22, 1899 – December 8, 1952) was an American New York socialite and publisher. By the end of the 1920s, he was a self-described "fascist".

Biography

Collins was born in Syracuse, New York to Irish Catholic paren ...

, these journals published the writings of the British Distributists, the New Humanists, the Southern Agrarians, T. S. Eliot, Christopher Dawson

Christopher Henry Dawson (12 October 188925 May 1970) was a British independent scholar, who wrote many books on cultural history and Christendom. Dawson has been called "the greatest English-speaking Catholic historian of the twentieth century ...

, ''et al''. Eventually, Collins drifted towards support of fascism and as a result lost the support of many of his traditionalist backers. Despite the decline of the journal due to Collins' increasingly radical political views, ''The American Review'' left a profound mark on the history of traditionalist conservatism.

Another intellectual branch of early-20th-century traditionalist conservatism was known as the New Humanism. Led by Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

professor Irving Babbitt

Irving Babbitt (August 2, 1865 – July 15, 1933) was an American academic and literary critic, noted for his founding role in a movement that became known as the New Humanism, a significant influence on literary discussion and conservative thou ...

and Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

professor Paul Elmer More

Paul Elmer More (December 12, 1864 – March 9, 1937) was an American journalist, critic, essayist and Christian apologist.

Biography

Paul Elmer More, the son of Enoch Anson and Katherine Hay Elmer, was born in St. Louis, Missouri. He was edu ...

, the New Humanism was a literary and social criticism movement that opposed both romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

and naturalism. Beginning in the late 19th century, the New Humanism defended artistic standards and "first principles" (Babbitt's phrase). Reaching an apogee in 1930, Babbitt and More published a variety of books including Babbitt's ''Literature and the American College'' (1908), ''Rousseau and Romanticism'' (1919) and '' Democracy and Leadership'' (1924) and More's ''Shelburne Essays'' (1904–1921).

One other group of traditionalist conservatives were the Southern Agrarians

The Southern Agrarians were twelve American Southerners who wrote an agrarian literary manifesto in 1930. They and their essay collection, ''I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition'', contributed to the Southern Renaissance, t ...

. Originally a group of Vanderbilt University

Vanderbilt University (informally Vandy or VU) is a private research university in Nashville, Tennessee. Founded in 1873, it was named in honor of shipping and rail magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt, who provided the school its initial $1-million ...

poets and writers known as "the Fugitives", they included John Crowe Ransom

John Crowe Ransom (April 30, 1888 – July 3, 1974) was an American educator, scholar, literary critic, poet, essayist and editor. He is considered to be a founder of the New Criticism school of literary criticism. As a faculty member at Kenyon ...

, Allen Tate

John Orley Allen Tate (November 19, 1899 – February 9, 1979), known professionally as Allen Tate, was an American poet, essayist, social commentator, and poet laureate from 1943 to 1944.

Life

Early years

Tate was born near Winchester, ...

, Donald Davidson and Robert Penn Warren

Robert Penn Warren (April 24, 1905 – September 15, 1989) was an American poet, novelist, and literary critic and was one of the founders of New Criticism. He was also a charter member of the Fellowship of Southern Writers. He founded the lit ...

. Adhering to strict literary standards (Warren and traditionalist scholar Cleanth Brooks

Cleanth Brooks ( ; October 16, 1906 – May 10, 1994) was an American literary critic and professor. He is best known for his contributions to New Criticism in the mid-20th century and for revolutionizing the teaching of poetry in American higher ...

later formulated a form of literary criticism known as the New Criticism), in 1930 some of the Fugitives joined other traditionalist Southern writers to publish ''I'll Take My Stand'', which applied standards sympathetic to local particularism and the agrarian way of life to politics and economics. Condemning northern industrialism and commercialism, the "twelve southerners" who contributed to the book echoed earlier arguments made by the distributists. A few years after the publication of ''I'll Take My Stand'', some of the Southern Agrarians were joined by Hilaire Belloc

Joseph Hilaire Pierre René Belloc (, ; 27 July 187016 July 1953) was a Franco-English writer and historian of the early twentieth century. Belloc was also an orator, poet, sailor, satirist, writer of letters, soldier, and political activist. ...

and Herbert Agar

Herbert Sebastian Agar (29 September 1897 – 24 November 1980) was an American journalist and historian, and an editor of the '' Louisville Courier-Journal''.

Early life

Herbert Sebastian Agar was born September 29, 1897 in New Rochelle, New Yor ...

in the publication of a new collection of essays entitled ''Who Owns America: A New Declaration of Independence''.

New conservatives

After World War II, the first stirrings of a "traditionalist movement" took place and among those who launched this movement (and in effect the larger Conservative Movement in America) wasUniversity of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

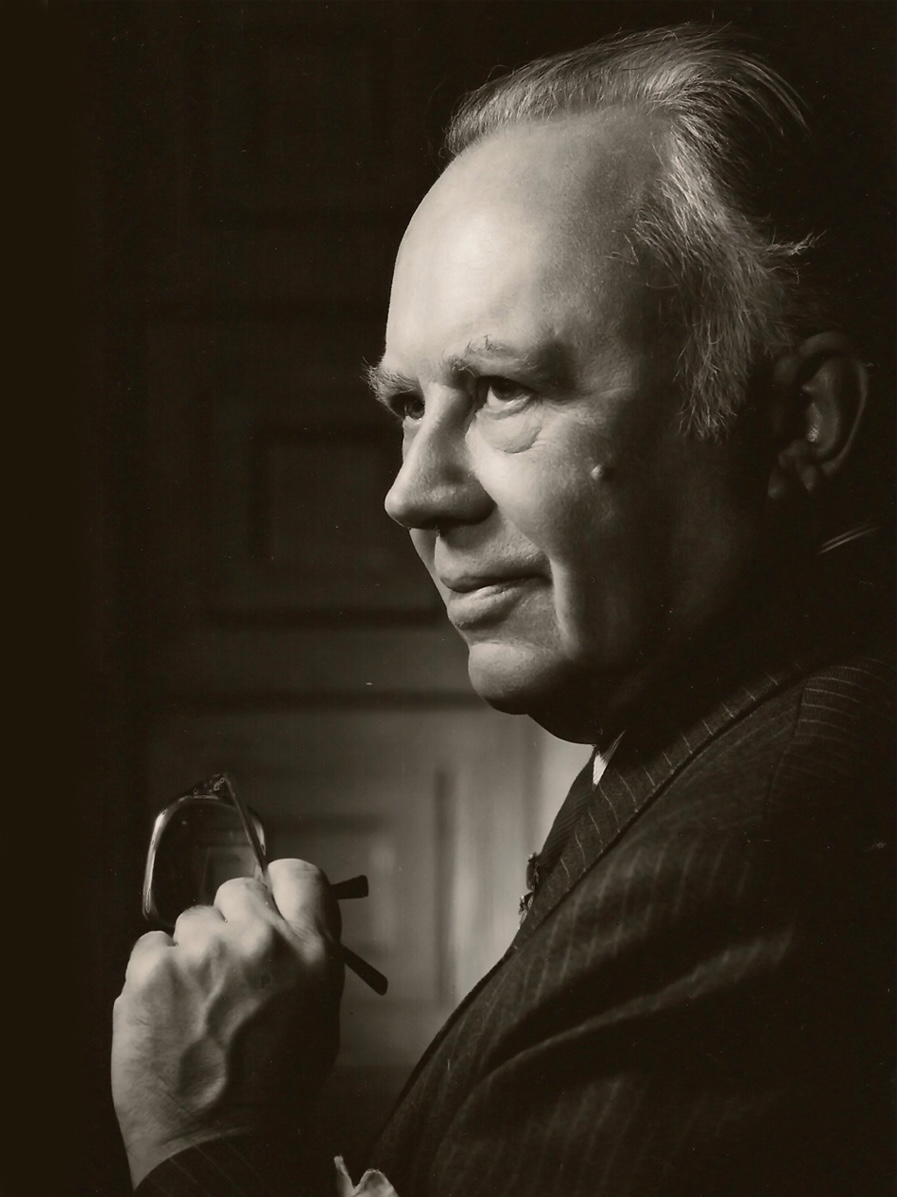

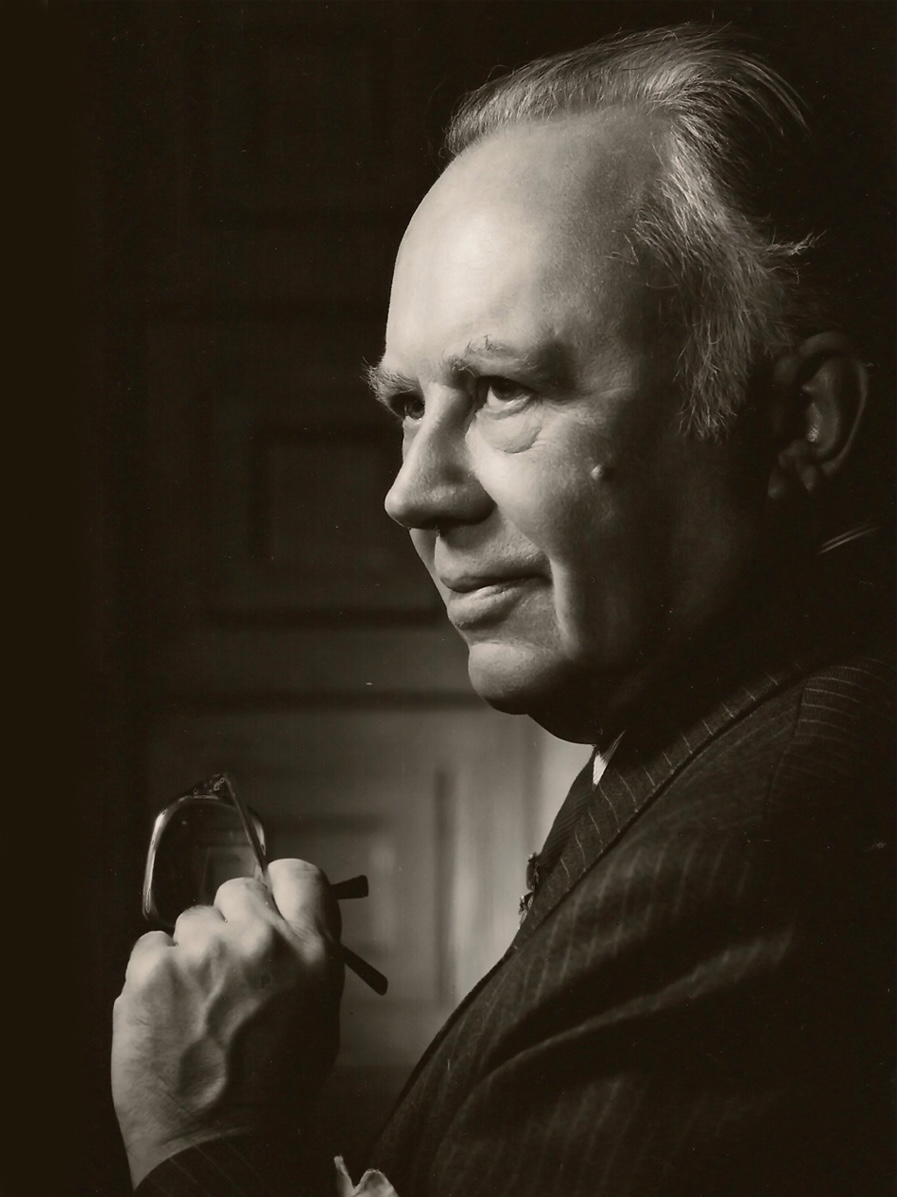

professor Richard M. Weaver

Richard Malcolm Weaver, Jr (March 3, 1910 – April 1, 1963) was an American scholar who taught English at the University of Chicago. He is primarily known as an intellectual historian, political philosopher, and a mid-20th century conservative a ...

. Weaver's ''Ideas Have Consequences

''Ideas Have Consequences'' is a philosophical work by Richard M. Weaver, published in 1948 by the University of Chicago Press. The book is largely a treatise on the harmful effects of nominalism on Western civilization since this doctrine gain ...

'' (1948) chronicled the steady erosion of Western cultural values since the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

. In 1949, another professor, Peter Viereck

Peter Robert Edwin Viereck (August 5, 1916 – May 13, 2006) was an American poet and professor of history at Mount Holyoke College. He won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1949 for the collection ''Terror and Decorum''.Klemens Metternich.

After Weaver and Viereck a flowering of conservative scholarship occurred starting with the publication of 1953's ''The New Science of Politics'' by  The acknowledged leader of the New Conservatives was independent scholar, writer, critic and man of letters

The acknowledged leader of the New Conservatives was independent scholar, writer, critic and man of letters

U.S. Senator Barry Goldwater gained national attention by way of '' The Conscience of a Conservative'', a book ghostwritten for him by L. Brent Bozell Jr. (

U.S. Senator Barry Goldwater gained national attention by way of '' The Conscience of a Conservative'', a book ghostwritten for him by L. Brent Bozell Jr. (

Eric Voegelin

Eric Voegelin (born Erich Hermann Wilhelm Vögelin, ; 1901–1985) was a German-American political philosopher. He was born in Cologne, and educated in political science at the University of Vienna, where he became an associate professor of poli ...

, 1953's ''The Quest for Community'' by Robert A. Nisbet and 1955's ''Conservatism in America'' by Clinton Rossiter

Clinton Lawrence Rossiter III (September 18, 1917 – July 11, 1970) was an American historian and political scientist at Cornell University (1947-1970) who wrote ''The American Presidency'', among 20 other books, and won both the Bancroft Prize ...

. However, the book that defined the traditionalist school was 1953's ''The Conservative Mind: From Burke to Eliot'', written by Russell Kirk

Russell Amos Kirk (October 19, 1918 – April 29, 1994) was an American political theorist, moralist, historian, social critic, and literary critic, known for his influence on 20th-century American conservatism. His 1953 book ''The Conservativ ...

, which gave a detailed analysis of the intellectual pedigree of Anglo-American traditionalist conservatism

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

.

When these thinkers appeared on the academic scene they became known for rebuking the progressive worldview inherent in an America comfortable with New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Con ...

economics, a burgeoning military–industrial complex

The expression military–industrial complex (MIC) describes the relationship between a country's military and the defense industry that supplies it, seen together as a vested interest which influences public policy. A driving factor behind the ...

and a consumerist and commercialized citizenry. These conservative scholars and writers garnered the attention of the popular press of the time and before long they were collectively referred to as "the New Conservatives". Among this group were not only Weaver, Viereck, Voegelin, Nisbet, Rossiter and Kirk, but other lesser known thinkers such as John Blum, Daniel Boorstin

Daniel Joseph Boorstin (October 1, 1914 – February 28, 2004) was an American historian at the University of Chicago who wrote on many topics in American and world history. He was appointed the twelfth Librarian of the United States Congress i ...

, McGeorge Bundy, Thomas Cook, Raymond English, John Hallowell, Anthony Harrigan, August Heckscher, Milton Hindus, Klemens von Klemperer, Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn

Erik Maria Ritter von Kuehnelt-Leddihn (; 31 July 1909 – 26 May 1999) was an Austrian political scientist and philosopher. He opposed the ideas of the French Revolution as well as those of communism and Nazism. Describing himself as a "conserv ...

, Richard Leopold, S. A. Lukacs, Malcolm Moos, Eliseo Vivas, Geoffrey Wagner, Chad Walsh and Francis Wilson, as well as Arthur Bestor, Mel Bradford

Melvin E. Bradford (May 8, 1934 – March 3, 1993) was an American conservative political commentator and professor of literature at the University of Dallas.

Bradford is seen as a leading figure of the paleoconservative wing of the conservativ ...

, C. P. Ives, Stanley Jaki

Stanley L. Jaki (Jáki Szaniszló László) (17 August 1924 in Győr, Hungary – 7 April 2009 in Madrid, Spain) was a Hungarian-born priest of the Benedictine order. From 1975 to his death, he was Distinguished University Professor at Seton H ...

, John Lukacs

John Adalbert Lukacs (; Hungarian: ''Lukács János Albert''; 31 January 1924 – 6 May 2019) was a Hungarian-born American historian and author of more than thirty books. Lukacs was Roman Catholic. Lukacs described himself as a reactionary.

L ...

, Forrest McDonald

Forrest McDonald, Jr. (January 7, 1927 – January 19, 2016) was an American historian who wrote extensively on the early national period of the United States, republicanism, and the presidency, but he is possibly best known for his polemic on the ...

, Thomas Molnar

Thomas Steven Molnar (; hu, Molnár Tamás; 26 July 1921, in Budapest, Hungary – 20 July 2010, in Richmond, Virginia) was a Catholic philosopher, historian and political theorist.

Life

Molnar completed his undergraduate studies at the Univer ...

, Gerhard Neimeyer, James V. Schall, S.J., Peter J. Stanlis, Stephen J. Tonsor and Frederick Wilhelmsen. The acknowledged leader of the New Conservatives was independent scholar, writer, critic and man of letters

The acknowledged leader of the New Conservatives was independent scholar, writer, critic and man of letters Russell Kirk

Russell Amos Kirk (October 19, 1918 – April 29, 1994) was an American political theorist, moralist, historian, social critic, and literary critic, known for his influence on 20th-century American conservatism. His 1953 book ''The Conservativ ...

. Kirk was a key figure of the conservative movement: he was a friend to William F. Buckley, Jr.

William Frank Buckley Jr. (born William Francis Buckley; November 24, 1925 – February 27, 2008) was an American public intellectual, conservative author and political commentator. In 1955, he founded ''National Review'', the magazine that stim ...

, a columnist for ''National Review

''National Review'' is an American conservative editorial magazine, focusing on news and commentary pieces on political, social, and cultural affairs. The magazine was founded by the author William F. Buckley Jr. in 1955. Its editor-in-chief ...

'', an editor and a syndicated columnist, as well as a historian and horror fiction writer. His most famous work was 1953's ''The Conservative Mind: From Burke to Santayana'' (later republished as ''The Conservative Mind: From Burke to Eliot''). Kirk's writings and legacy are interwoven with the history of traditionalist conservatism, with his influence felt at the Heritage Foundation

The Heritage Foundation (abbreviated to Heritage) is an American conservative think tank based in Washington, D.C. that is primarily geared toward public policy. The foundation took a leading role in the conservative movement during the preside ...

, the Intercollegiate Studies Institute

The Intercollegiate Studies Institute (ISI) is a nonprofit educational organization that promotes conservative thought on college campuses.

It was founded in 1953 by Frank Chodorov with William F. Buckley Jr. as its first president. It sponsor ...

and other conservative think tanks (most especially the Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal).

''The Conservative Mind'' was written by Kirk as a doctoral dissertation while he was a student at the St. Andrews University in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

. Previously the author of a biography of American conservative John Randolph of Roanoke

John Randolph (June 2, 1773May 24, 1833), commonly known as John Randolph of Roanoke,''Roanoke'' refers to Roanoke Plantation in Charlotte County, Virginia, not to the city of the same name. was an American planter, and a politician from Virg ...

, Kirk's ''The Conservative Mind'' had laid out six "canons of conservative thought" in the book, including:

# Belief that a divine intent rules society as well as conscience... Political problems, at bottom, are religious and moral problems.

# Affection for the proliferating variety and mystery of traditional life, as distinguished from the narrowing uniformity and egalitarian and utilitarian aims of most radical systems.

# Conviction that civilized society requires orders and classes...

# Persuasion that property and freedom are inseparably connected, and that economic leveling is not economic progress...

# Faith in prescription and distrust of "sophisters and calculators." Man must put a control upon his will and his appetite.... Tradition and sound prejudice provide checks upon man's anarchic impulse.

# Recognition that change and reform are not identical...

Goldwater movement and its aftermath

U.S. Senator Barry Goldwater gained national attention by way of '' The Conscience of a Conservative'', a book ghostwritten for him by L. Brent Bozell Jr. (

U.S. Senator Barry Goldwater gained national attention by way of '' The Conscience of a Conservative'', a book ghostwritten for him by L. Brent Bozell Jr. (William F. Buckley, Jr.

William Frank Buckley Jr. (born William Francis Buckley; November 24, 1925 – February 27, 2008) was an American public intellectual, conservative author and political commentator. In 1955, he founded ''National Review'', the magazine that stim ...

's Catholic traditionalist brother-in-law). The book advocated a conservative vision in keeping with Buckley's ''National Review'' and propelled Goldwater to challenge Vice President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

, without success, for the 1960 Republican presidential nomination.

In 1964, Goldwater returned to challenge the Eastern Establishment, which since the 1930s had controlled the Republican Party. In a brutal campaign where he was maligned by liberal Republican primary rivals (Rockefeller, Romney, Scranton, etc.), the press, the Democrats and President Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

, Goldwater again found allies among conservatives, including the traditionalists. Russell Kirk

Russell Amos Kirk (October 19, 1918 – April 29, 1994) was an American political theorist, moralist, historian, social critic, and literary critic, known for his influence on 20th-century American conservatism. His 1953 book ''The Conservativ ...

championed Goldwater's cause as the maturation of the New Right in American politics. Kirk advocated for Goldwater in his syndicated columns and campaigned for him in the primaries. Goldwater's subsequent defeat would result in the New Right regrouping and finding a new figurehead in the late 1970s: Ronald Reagan.

Fundamental differences developed between libertarians and traditional conservatives. Libertarians wanted the free market to be unregulated as possible while traditional conservatives believed that big business, if unconstrained, could impoverish national life and threaten freedom. Libertarians also believed that a strong state would threaten freedom while traditional conservatives regarded a strong state, one which is properly constructed to ensure that not too much power accumulated in any one branch, was necessary to ensure freedom.

Leading 20th and 21st century traditionalist figures

FormerTennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

Republican Senator Fred Thompson, former Michigan

Michigan () is a U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest, upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the List of U.S. states and ...

Republican Senator Spencer Abraham

Edward Spencer Abraham (born June 12, 1952) is an American attorney, author, and politician who served as the tenth United States Secretary of Energy from 2001 to 2005, under President George W. Bush. A member of the Republican Party, Abraham pr ...

and former Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rockf ...

Democratic Senator Paul Simon have all been influenced by traditionalist conservative Russell Kirk

Russell Amos Kirk (October 19, 1918 – April 29, 1994) was an American political theorist, moralist, historian, social critic, and literary critic, known for his influence on 20th-century American conservatism. His 1953 book ''The Conservativ ...

.Person, James E. Jr. ''Russell Kirk: A Critical Biography of a Conservative Mind''. Lanham, MD: Madison Books, p. 217. Thompson gave an interview about Kirk's influence on the Russell Kirk Center's blog. Among the U.S. Congressmen influenced by Kirk are former Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rockf ...

Republican Congressman Henry Hyde

Henry John Hyde (April 18, 1924 – November 29, 2007) was an American politician who served as a Republican member of the United States House of Representatives from 1975 to 2007, representing the 6th District of Illinois, an area of Chicago's ...

and Michigan

Michigan () is a U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest, upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the List of U.S. states and ...

Republican Congressmen Thaddeus McCotter and Dave Camp, the latter two of whom visited the Russell Kirk Center in 2009. In 2010, then-Congressman Mike Pence acknowledged Kirk as a major influence. Former Michigan

Michigan () is a U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest, upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the List of U.S. states and ...

Republican Governor John Engler

John Mathias Engler (born October 12, 1948) is an American businessman and politician who served as the 46th Governor of Michigan from 1991 to 2003. A member of the Republican Party, he later worked for Business Roundtable, where ''The Hill'' c ...

is a close personal friend of the Kirk family and also serves as a trustee of the Wilbur Foundation, which funds programs at the Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal in Mecosta, Michigan. Engler gave a speech at the Heritage Foundation on Kirk which is available from the Russell Kirk Center's blog.

Other influences

Traditionalist conservative influences on those who emerged in the 1940s and 1950s as "the New Conservatives" included Bernard Iddings Bell, Gordon Keith Chalmers, Grenville Clark,Peter Drucker

Peter Ferdinand Drucker (; ; November 19, 1909 – November 11, 2005) was an Austrian-American management consultant, educator, and author, whose writings contributed to the philosophical and practical foundations of the modern business co ...

, Will Herberg

William Herberg (June 30, 1901 – March 26, 1977) was an American writer, intellectual and scholar. A communist political activist during his early years, Herberg gained wider public recognition as a social philosopher and sociologist of relig ...

and Ross J. S. Hoffman.Viereck, Peter (1956, 2006) ''Conservative Thinkers from John Adams to Winston Churchill''. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, p. 107.

Organizations

*Intercollegiate Studies Institute

The Intercollegiate Studies Institute (ISI) is a nonprofit educational organization that promotes conservative thought on college campuses.

It was founded in 1953 by Frank Chodorov with William F. Buckley Jr. as its first president. It sponsor ...

* Philadelphia Society

The Philadelphia Society is a membership organization the purpose of which is "to sponsor the interchange of ideas through discussion and writing, in the interest of deepening the intellectual foundation of a free and ordered society, and of bro ...

* Howard Center for Family, Religion and Society

* National Humanities Institute

* Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal

Journals, periodicals and reviews

* '' Modern Age: A Quarterly Review'' * '' Touchstone Magazine'' * ''The University Bookman'' * ''The Political Science Reviewer'' * '' The Chesterton Review'' * ''Image: A Journal of the Arts and Religion''See also

* Conservatism in the United States *Traditionalist conservatism

Traditionalist conservatism, often known as classical conservatism, is a political and social philosophy that emphasizes the importance of transcendent moral principles, manifested through certain natural laws to which society should adhere ...

* Traditional Values Coalition

The Traditional Values Coalition (TVC) was an American conservative Christian organization. It was founded in Orange County, California by Rev. Louis P. Sheldon to oppose LGBT rights. Sheldon's daughter, Andrea Sheldon Lafferty, was the execut ...

References

Bibliography

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Traditionalist Conservatism Conservatism in the United States