Tongva on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Tongva ( ) are an Indigenous people of California from the

Tongva territories border those of numerous other tribes in the region. The historical Tongva lands made up what is now called "the coastal region of

Tongva territories border those of numerous other tribes in the region. The historical Tongva lands made up what is now called "the coastal region of

The word ''Tongva'' was coined by

The word ''Tongva'' was coined by

Many lines of evidence suggest that the Tongva are descended from

Many lines of evidence suggest that the Tongva are descended from

The

The  There is much evidence of Tongva resistance to the mission system. Many individuals returned to their village at time of death. Many converts retained their traditional practices in both domestic and spiritual contexts, despite the attempts by the padres and missionaries to control them. Traditional foods were incorporated into the mission diet and lithic and shell bead production and use persisted. More overt strategies of resistance such as refusal to enter the system, work slowdowns, abortion and infanticide of children resulting from rape, and fugitivism were also prevalent. Five major uprisings were recorded at Mission San Gabriel alone. Two late-eighteenth century rebellions against the mission system were led by Nicolás José, who was an early convert who had two social identities: "publicly participating in Catholic sacraments at the mission but privately committed to traditional dances, celebrations, and rituals." He participated in a failed attempt to kill the mission's priests in 1779 and organized eight foothill villages in a revolt in October 1785 with

There is much evidence of Tongva resistance to the mission system. Many individuals returned to their village at time of death. Many converts retained their traditional practices in both domestic and spiritual contexts, despite the attempts by the padres and missionaries to control them. Traditional foods were incorporated into the mission diet and lithic and shell bead production and use persisted. More overt strategies of resistance such as refusal to enter the system, work slowdowns, abortion and infanticide of children resulting from rape, and fugitivism were also prevalent. Five major uprisings were recorded at Mission San Gabriel alone. Two late-eighteenth century rebellions against the mission system were led by Nicolás José, who was an early convert who had two social identities: "publicly participating in Catholic sacraments at the mission but privately committed to traditional dances, celebrations, and rituals." He participated in a failed attempt to kill the mission's priests in 1779 and organized eight foothill villages in a revolt in October 1785 with

The mission period ended in 1834 with secularization under Mexican rule. Some "Gabrieleño" absorbed into Mexican society as a result of secularization, which emancipated the neophytes. Tongva and other California Natives largely became workers while former Spanish elites were granted huge land grants. Land was systemically denied to California Natives by ''

The mission period ended in 1834 with secularization under Mexican rule. Some "Gabrieleño" absorbed into Mexican society as a result of secularization, which emancipated the neophytes. Tongva and other California Natives largely became workers while former Spanish elites were granted huge land grants. Land was systemically denied to California Natives by ''

Landless and unrecognized, the people faced continued violence, subjugation, and enslavement (through convict labor) under American occupation. Some of the people were displaced to small Mexican and Native communities in the Eagle Rock and Highland Park districts of Los Angeles as well as Pauma,

Landless and unrecognized, the people faced continued violence, subjugation, and enslavement (through convict labor) under American occupation. Some of the people were displaced to small Mexican and Native communities in the Eagle Rock and Highland Park districts of Los Angeles as well as Pauma,

By the early twentieth century, Gabrieleño identity had suffered greatly under American occupation. Most Gabrieleño publicly identified as Mexican, learned Spanish, and adopted Catholicism while keeping their identity a secret. In schools, students were punished for mentioning that they were "Indian" and many of the people assimilated into

By the early twentieth century, Gabrieleño identity had suffered greatly under American occupation. Most Gabrieleño publicly identified as Mexican, learned Spanish, and adopted Catholicism while keeping their identity a secret. In schools, students were punished for mentioning that they were "Indian" and many of the people assimilated into

The continued denigration and denial of Gabrieleño identity perpetuated by Anglo-American institutions such as schools and museums has presented numerous obstacles for the people throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Contemporary members have cited being denied the legitimacy of their identity. Tribal identity is also heavily hindered by a lack of federal recognition and having no land base.

Being denied federal recognition has prevented the Tongva from protecting their sacred sites, ancestral remains, and artifacts which have faced continued destruction in the 21st century. In 2001, a 9,000-year-old

The continued denigration and denial of Gabrieleño identity perpetuated by Anglo-American institutions such as schools and museums has presented numerous obstacles for the people throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Contemporary members have cited being denied the legitimacy of their identity. Tribal identity is also heavily hindered by a lack of federal recognition and having no land base.

Being denied federal recognition has prevented the Tongva from protecting their sacred sites, ancestral remains, and artifacts which have faced continued destruction in the 21st century. In 2001, a 9,000-year-old

The Tongva lived in the main part of the most fertile lowland of southern California, including a stretch of sheltered coast with a pleasant climate and abundant food resources, and the most habitable of the Santa Barbara Islands. They have been referred to as the most culturally 'advanced' group south of the Tehachapi, and the wealthiest of the

The Tongva lived in the main part of the most fertile lowland of southern California, including a stretch of sheltered coast with a pleasant climate and abundant food resources, and the most habitable of the Santa Barbara Islands. They have been referred to as the most culturally 'advanced' group south of the Tehachapi, and the wealthiest of the

Los Angeles Basin

The Los Angeles Basin is a sedimentary basin located in Southern California, in a region known as the Peninsular Ranges. The basin is also connected to an anomalous group of east-west trending chains of mountains collectively known as the ...

and the Southern Channel Islands, an area covering approximately . Some descendants of the people prefer Kizh

Kizh Kit’c () are the Mission Indians of San Gabriel, according to Andrew Salas, Smithsonian Institution, Congress, the Catholic Church, the San Gabriel Mission, and other Indigenous communities. Most California tribes were known by their com ...

as an endonym

An endonym (from Greek: , 'inner' + , 'name'; also known as autonym) is a common, ''native'' name for a geographical place, group of people, individual person, language or dialect, meaning that it is used inside that particular place, group, ...

that, they argue, is more historically accurate. In the precolonial era, the people lived in as many as 100 villages and primarily identified by their village rather than by a pan-tribal name. During colonization

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

, the Spanish referred to these people as Gabrieleño and Fernandeño, names derived from the Spanish missions

The Spanish missions in the Americas were Catholic missions established by the Spanish Empire during the 16th to 19th centuries in the period of the Spanish colonization of the Americas. These missions were scattered throughout the entirety of ...

built on their land: Mission San Gabriel Arcángel

Mission San Gabriel Arcángel ( es, Misión de San Gabriel Arcángel) is a Californian mission and historic landmark in San Gabriel, California. It was founded by Spaniards of the Franciscan order on "The Feast of the Birth of Mary," September ...

and Mission San Fernando Rey de España

Mission San Fernando Rey de España is a Spanish mission in the Mission Hills community of Los Angeles, California. The mission was founded on 8 September 1797 at the site of Achooykomenga, and was the seventeenth of the twenty-one Spanish mis ...

. ''Tongva'' is the most widely circulated endonym among the people, used by Narcisa Higuera in 1905 to refer to inhabitants in the vicinity of Mission San Gabriel.

Along with the neighboring Chumash Chumash may refer to:

*Chumash (Judaism), a Hebrew word for the Pentateuch, used in Judaism

*Chumash people, a Native American people of southern California

*Chumashan languages, indigenous languages of California

See also

*Chumash traditional n ...

, the Tongva were the most influential people at the time of European encounter. They had developed an extensive trade network

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct excha ...

through '' te'aats'' (plank-built boats). Their vibrant food and material culture was based on an Indigenous worldview that positioned humans as one strand in a web of life

A food web is the natural interconnection of food chains and a graphical representation of what-eats-what in an ecological community. Another name for food web is consumer-resource system. Ecologists can broadly lump all life forms into one o ...

(as expressed in their creation stories

A creation myth (or cosmogonic myth) is a symbolic narrative of how the world began and how people first came to inhabit it., "Creation myths are symbolic stories describing how the universe and its inhabitants came to be. Creation myths develop ...

). Over time, different communities came to speak distinct dialects of the Tongva language

The Tongva language (also known as Gabrielino or Gabrieleño) is an extinct Uto-Aztecan language formerly spoken by the Tongva, a Native American people who live in and around Los Angeles, California. It has not been a language of everyday conve ...

, part of the Takic subgroup of the Uto-Aztecan language

Uto-Aztecan, Uto-Aztekan or (rarely in English) Uto-Nahuatl is a family of indigenous languages of the Americas, consisting of over thirty languages. Uto-Aztecan languages are found almost entirely in the Western United States and Mexico. Th ...

family. There may have been five or more such languages (three on the southernmost Channel Islands and at least two on the mainland).

European contact was first made in 1542 by Spanish explorer Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo

''Juan'' is a given name, the Spanish and Manx versions of '' John''. It is very common in Spain and in other Spanish-speaking communities around the world and in the Philippines, and also (pronounced differently) in the Isle of Man. In Spanis ...

, who was greeted at Santa Catalina by the people in a canoe. The following day, Cabrillo and his men entered a large bay on the mainland, which they named ''Baya de los Fumos'' ("Bay of Smokes") because of the many smoke fires they saw there. The indigenous people smoked their fish for preservation. This is commonly believed to be San Pedro Bay, near present-day San Pedro.

The Gaspar de Portolá

Gaspar de Portolá y Rovira (January 1, 1716 – October 10, 1786) was a Spanish military officer, best known for leading the Portolá expedition into California and for serving as the first Governor of the Californias. His expedition laid t ...

land expedition in 1769 resulted in the founding of Mission San Gabriel by Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι� ...

missionary Junipero Serra in 1771. Under the mission system, the Spanish initiated an era of forced relocation

Forced displacement (also forced migration) is an involuntary or coerced movement of a person or people away from their home or home region. The UNHCR defines 'forced displacement' as follows: displaced "as a result of persecution, conflict, g ...

and virtual enslavement of the peoples to secure their labor. In addition, the Native Americans were exposed to the Old World

The "Old World" is a term for Afro-Eurasia that originated in Europe , after Europeans became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, which were previously thought of by thei ...

diseases endemic among the colonists. As they lacked any acquired immunity, the Native Americans suffered epidemics with high mortality, leading to the rapid collapse of Tongva society and lifeway

Lifeway is a term used in the disciplines of anthropology, sociology and archeology, particularly in North America.

History Literature

From the mid 19th century, the word was used with the meaning 'way through life' or 'way of life'. It a ...

s.

They retaliated by resistance and rebellions, including an unsuccessful rebellion in 1785 by Nicolás José and female chief Toypurina

Toypurina (1760–1799) was a Kizhhttps://gabrielenoindians.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Toypurina_Raeganletter_220909_154647_page-0001-1_220909_155854.pdf medicine woman from the Jachivit village. She is notable for her opposition to the c ...

. In 1821, Mexico gained its independence from Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

and secularized the missions. They sold the mission lands, known as ranchos, to elite ranchers and forced the Tongva to assimilate. Most became landless refugees during this time.

In 1848, California was ceded to the United States following the Mexican-American War

Mexican Americans ( es, mexicano-estadounidenses, , or ) are Americans of full or partial Mexican heritage. In 2019, Mexican Americans comprised 11.3% of the US population and 61.5% of all Hispanic and Latino Americans. In 2019, 71% of Mexica ...

. The US government signed 18 treaties between 1851 and 1852 promising of land for reservations. However, these treaties were never ratified by the Senate. The US had negotiated with people who did not represent the Tongva and had no authority to cede their land. During the following occupation by Americans, many of the Tongva and other indigenous peoples were targeted with arrest

An arrest is the act of apprehending and taking a person into custody (legal protection or control), usually because the person has been suspected of or observed committing a crime. After being taken into custody, the person can be questi ...

. Unable to pay fines, they were used as convict laborers in a system of legalized slavery to expand the city of Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world ...

for Anglo-American

Anglo-Americans are people who are English-speaking inhabitants of Anglo-America. It typically refers to the nations and ethnic groups in the Americas that speak English as a native language, making up the majority of people in the world who spe ...

settlers, who became the new majority in the area by 1880.

In the early 20th century, an extinction myth was purported about the Gabrieleño, who largely identified publicly as Mexican-American

Mexican Americans ( es, mexicano-estadounidenses, , or ) are Americans of full or partial Mexican heritage. In 2019, Mexican Americans comprised 11.3% of the US population and 61.5% of all Hispanic and Latino Americans. In 2019, 71% of Mexica ...

by this time. However, a close-knit community of the people remained in contact with one another between Tejon Pass

The Tejon Pass , previously known as ''Portezuelo de Cortes'', ''Portezuela de Castac'', and Fort Tejon Pass is a mountain pass between the southwest end of the Tehachapi Mountains and northeastern San Emigdio Mountains, linking Southern Calif ...

and San Gabriel township into the 20th century. Since 2006, four organizations have claimed to represent the people:

*the Gabrielino-Tongva Tribe, known as the "hyphen" group from the hyphen in their name;

*the Gabrielino/Tongva Tribe, known as the "slash" group;

*the Kizh Nation (Gabrieleño Band of Mission Indians); and

*the Gabrieleño/Tongva Tribal Council.

Two of the groups, the hyphen and the slash group, were founded after a hostile split over the question of building an Indian casino

Native American gaming comprises casinos, bingo halls, and other gambling operations on Indian reservations or other tribal lands in the United States. Because these areas have tribal sovereignty, states have limited ability to forbid gambling t ...

. In 1994, the state of California recognized the Gabrielino "as the aboriginal tribe of the Los Angeles Basin." No organized group representing the Tongva has attained recognition as a tribe by the federal government. The lack of federal recognition has prevented the Tongva from having control over their ancestral remains, artifacts, and has left them without a land base in their traditional homelands.

In 2008, more than 1,700 people identified as Tongva or claimed partial ancestry. In 2013, it was reported that the four Tongva groups that have applied for federal recognition had more than 3,900 members in total.

Geography

Tongva territories border those of numerous other tribes in the region. The historical Tongva lands made up what is now called "the coastal region of

Tongva territories border those of numerous other tribes in the region. The historical Tongva lands made up what is now called "the coastal region of Los Angeles County

Los Angeles County, officially the County of Los Angeles, and sometimes abbreviated as L.A. County, is the List of the most populous counties in the United States, most populous county in the United States and in the U.S. state of California, ...

, the northwest portion of Orange County and off-lying islands.” In 1962 Curator Bernice Johnson, of Southwest Museum

The Southwest Museum of the American Indian is a museum, library, and archive located in the Mt. Washington neighborhood of Los Angeles, California, above the north-western bank of the Arroyo Seco (Los Angeles County) canyon and stream. The muse ...

, asserted that the northern bound was somewhere between Topanga and Malibu (perhaps the vicinity of Malibu Creek

Malibu Creek is a year-round stream in western Los Angeles County, California. It drains the southern Conejo Valley and Simi Hills, flowing south through the Santa Monica Mountains, and enters Santa Monica Bay in Malibu, California. The Malibu C ...

) and the southern bound was Orange County’s Aliso Creek.

Name

''Tongva''

The word ''Tongva'' was coined by

The word ''Tongva'' was coined by C. Hart Merriam

Clinton Hart Merriam (December 5, 1855 – March 19, 1942) was an American zoologist, mammalogist, ornithologist, entomologist, ecologist, ethnographer, geographer, naturalist and physician. He was commonly known as the 'father of mammalogy', a ...

in 1905 from numerous informants. These included Mrs. James Rosemyre (née Narcisa Higuera) (Gabrileño), who lived around Fort Tejon

Fort Tejon in California is a former United States Army outpost which was intermittently active from June 24, 1854, until September 11, 1864. It is located in the Grapevine Canyon (''La Cañada de las Uvas'') between the San Emigdio Mountains and ...

, near Bakersfield. Merriam's orthography makes it clear that the endonym would be pronounced , .

An earlier and more historically accurate name for the indigenous population of the Los Angeles/Orange County basin is the Kizh

Kizh Kit’c () are the Mission Indians of San Gabriel, according to Andrew Salas, Smithsonian Institution, Congress, the Catholic Church, the San Gabriel Mission, and other Indigenous communities. Most California tribes were known by their com ...

; this was well documented by records of the Smithsonian Institution, Congress, the Catholic Church, the San Gabriel Mission, and other historical scholars.

''Gabrieleño''

The Spanish referred to the indigenous peoples surrounding Mission San Gabriel as the ''Gabrieleño''. This was not their autonym, or their name for themselves. Because of historical uses, the term is part of every official tribe's name in this area, spelled either as "Gabrieleño" or "Gabrielino." Because tribal groups have disagreed about appropriate use of the term ''Tongva'', they have adopted ''Gabrieleño'' as a mediating term. For example, when Debra Martin, a city council member from Pomona, led a project in 2017 to dedicate wooden statues in local Ganesha Park to the Indigenous people of the area, they disagreed over which name, ''Tongva'' or ''Kizh'', should be used on the dedication plaque. Tribal officials tentatively agreed to use the term ''Gabrieleño.'' The Act of September 21, 1968, introduced this concept of the affiliation of an applicant’s ancestors in order to exclude certain individuals from receiving a share of the award to the “Indians of California” who chose to receive a share of any awards to certain tribes in California that had splintered off from the generic group. The members or ancestors of the petitioning group were not affected by the exclusion in the Act. Individuals with lineal or collateral descent from an Indian tribe who resided in California in 1852, would, if not excluded by the provisions of the Act of 1968, remain on the list of the “Indians of California.” To comply with the Act, the Secretary of Interior would have to collect information about the group affiliation of an applicant’s Indian ancestors. That information would be used to identify applicants who could share in another award. The group affiliation of an applicant’s ancestors was thus a basis for exclusion from, but not a requirement for inclusion on, the judgment roll. The act of 1968 stated that the Secretary of the Interior would distribute an equal share of the award to the individuals on the judgment roll “regardless of group affiliation.”History

Before the mission period

Many lines of evidence suggest that the Tongva are descended from

Many lines of evidence suggest that the Tongva are descended from Uto-Aztecan

Uto-Aztecan, Uto-Aztekan or (rarely in English) Uto-Nahuatl is a family of indigenous languages of the Americas, consisting of over thirty languages. Uto-Aztecan languages are found almost entirely in the Western United States and Mexico. The na ...

-speaking peoples who originated in what is now Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. N ...

, and moved southwest into coastal Southern California 3,500 years ago. According to a model proposed by archaeologist Mark Q. Sutton, these migrants either absorbed or pushed out the earlier Hokan-speaking inhabitants. By 500 AD, one source estimates the Tongva may have come to occupy all the lands now associated with them, although this is unclear and contested among scholars.

In 1811, the priests of Mission San Gabriel recorded at least four languages; Kokomcar, Guiguitamcar, Corbonamga, and Sibanga. During the same time, three languages were recorded in Mission San Fernando.

Prior to Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

and Spanish colonization in what is now referred to California, the Tongva primarily identified by their associated villages ( Topanga, Cahuenga, Tujunga, Cucamonga

Rancho Cucamonga ( ) is a city located just south of the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains and Angeles National Forest in San Bernardino County, California, United States. About east of Downtown Los Angeles, Rancho Cucamonga is the 28th ...

, etc.) For example, individuals from Yaanga

Yaanga was a large Tongva (or Kizh) village originally located near what is now downtown Los Angeles, just west of the Los Angeles River and beneath U.S. Route 101. People from the village were recorded as ''Yabit'' in missionary records althou ...

were known as ''Yaangavit'' among the people (in mission records, they were recorded as ''Yabit''). The Tongva lived in as many as one hundred villages. One or two clans would usually constitute a village, which was the center of Tongva life.

The Tongva spoke a language of the Uto-Aztecan

Uto-Aztecan, Uto-Aztekan or (rarely in English) Uto-Nahuatl is a family of indigenous languages of the Americas, consisting of over thirty languages. Uto-Aztecan languages are found almost entirely in the Western United States and Mexico. The na ...

family (the remote ancestors of the Tongva probably coalesced as a people in the Sonoran Desert

The Sonoran Desert ( es, Desierto de Sonora) is a desert in North America and ecoregion that covers the northwestern Mexican states of Sonora, Baja California, and Baja California Sur, as well as part of the southwestern United States (in Ariz ...

, between perhaps 3,000 and 5,000 years ago). The diversity within the Takic group is "moderately deep"; rough estimates by comparative linguists place the breakup of common Takic into the Luiseño-Juaneño on one hand, and the Tongva- Serrano on the other, at about 2,000 years ago. (This is comparable to the differentiation of the Romance languages

The Romance languages, sometimes referred to as Latin languages or Neo-Latin languages, are the various modern languages that evolved from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic languages in the Indo-European language ...

of Europe). The division of the Tongva/Serrano group into the separate Tongva and Serrano people

The Serrano are an indigenous people of California. They use the autonyms of Taaqtam, meaning "people"; Maarrênga’yam, "people from Morongo"; and Yuhaaviatam, "people of the pines." Today the Maarrênga'yam are enrolled in the Morongo Band ...

s is more recent, and may have been influenced by Spanish missionary activity.

The majority of Tongva territory was located in what has been referred to as the Sonoran life zone, with rich ecological resources of acorn, pine nut, small game, and deer. On the coast, shellfish, sea mammals, and fish were available. Prior to Christianization

Christianization ( or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of an individual, a practice, a place or a whole society. It began in the Roman Empire, conti ...

, the prevailing Tongva worldview was that humans were not the apex of creation, but were rather one strand in the web of life

A food web is the natural interconnection of food chains and a graphical representation of what-eats-what in an ecological community. Another name for food web is consumer-resource system. Ecologists can broadly lump all life forms into one o ...

. Humans, along with plants, animals, and the land were in a reciprocal relationship of mutual respect and care, which is evident in their creation stories. The Tongva understand time as nonlinear

In mathematics and science, a nonlinear system is a system in which the change of the output is not proportional to the change of the input. Nonlinear problems are of interest to engineers, biologists, physicists, mathematicians, and many oth ...

and there is constant communication with ancestors.

On October 7, 1542, an exploratory expedition led by Spanish explorer Juan Cabrillo

''Juan'' is a given name, the Spanish and Manx versions of ''John''. It is very common in Spain and in other Spanish-speaking communities around the world and in the Philippines, and also (pronounced differently) in the Isle of Man. In Spanish, ...

reached Santa Catalina in the Channel Islands, where his ships were greeted by Tongva in a canoe. The following day, Cabrillo and his men, the first Europeans known to have interacted with the Gabrieleño people, entered a large bay on the mainland, which they named "Baya de los Fumos" ("Bay of Smokes") on account of the many smoke fires they saw there. This is commonly believed to be San Pedro Bay, near present-day San Pedro.

Colonization and the mission period (1769–1834)

The

The Gaspar de Portola

Gaspar is a given and/or surname of French, German, Portuguese, and Spanish origin, cognate to Casper (given name) or Casper (surname).

It is a name of biblical origin, per Saint Gaspar, one of the wise men mentioned in the Bible.

Notable peopl ...

expedition in 1769 was the first contact by land to reach Tongva territory, marking the beginning of Spanish colonization. Franciscan

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

padre Junipero Serra accompanied Portola. Within two years of the expedition, Serra had founded four missions, including Mission San Gabriel, founded in 1771 and rebuilt in 1774, and Mission San Fernando

Mission (from Latin ''missio'' "the act of sending out") may refer to:

Organised activities Religion

*Christian mission, an organized effort to spread Christianity

*Mission (LDS Church), an administrative area of The Church of Jesus Christ of ...

, founded in 1797. The people enslaved at San Gabriel were referred to as ''Gabrieleños'', while those enslaved at San Fernando were referred to as ''Fernandeños''. Although their language idioms were distinguishable, they did not diverge greatly, and it is possible there were as many as half a dozen dialects rather than the two which the existence of the missions has lent the appearance of being standard. The demarcation of the Fernandeño and the Gabrieleño territories is mostly conjectural and there is no known point in which the two groups differed markedly in customs. The wider Gabrieleño group occupied what is now Los Angeles County

Los Angeles County, officially the County of Los Angeles, and sometimes abbreviated as L.A. County, is the List of the most populous counties in the United States, most populous county in the United States and in the U.S. state of California, ...

south of the Sierra Madre

Sierra Madre (Spanish, 'mother mountain range') may refer to:

Places and mountains Mexico

*Sierra Madre Occidental, a mountain range in northwestern Mexico and southern Arizona

*Sierra Madre Oriental, a mountain range in northeastern Mexico

*S ...

and half of Orange County, as well as the islands of Santa Catalina and San Clemente

San Clemente (; Spanish for " St. Clement") is a city in Orange County, California. Located in the Orange Coast region of the South Coast of California, San Clemente's population was 64,293 in at the 2020 census. Situated roughly midway between ...

.

The Spanish oversaw the construction of Mission San Gabriel in 1771. The Spanish colonizers used slave labor

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

from local villages to construct the Missions. Following the destruction of the original mission, probably due to El Nino

EL, El or el may refer to:

Religion

* El (deity), a Semitic word for "God"

People

* EL (rapper) (born 1983), stage name of Elorm Adablah, a Ghanaian rapper and sound engineer

* El DeBarge, music artist

* El Franco Lee (1949–2016), American po ...

flooding, the Spanish ordered the mission relocated five miles north in 1774 and began referring to the Tongva as "Gabrieleno." At the Gabrieleño settlement of Yaanga along the Los Angeles River

, name_etymology =

, image = File:Los Angeles River from Fletcher Drive Bridge 2019.jpg

, image_caption = L.A. River from Fletcher Drive Bridge

, image_size = 300

, map = LARmap.jpg

, map_size ...

, missionaries and Indian neophytes, or baptized converts, built the first town of Los Angeles in 1781. It was called ''El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles de Porciúncula'' (The Village of Our Lady, the Queen of the Angels of Porziuncola). In 1784, a sister mission, the ''Nuestra Señora Reina de los Angeles Asistencia

''Nuestra'' is the debut studio album of the Venezuelan rock band La Vida Bohème, released in August 2010. Recorded and produced by Rudy Pagliuca, it is a free download on the website of the record label All of the Above.

The album was nominate ...

'', was founded at Yaanga as well.

Entire villages were baptized and indoctrinated into the mission system with devastating results. For example, from 1788 to 1815, natives of the village of Guaspet were baptized at San Gabriel. Proximity to the missions created mass tension for Native Californians, which initiated "forced transformations in all aspects of daily life, including manners of speaking, eating, working, and connecting with the supernatural." As stated by scholars John Dietler, Heather Gibson, and Benjamin Vargas, "Catholic enterprises of proselytization

Proselytism () is the policy of attempting to convert people's religious or political beliefs. Proselytism is illegal in some countries.

Some draw distinctions between '' evangelism'' or '' Da‘wah'' and proselytism regarding proselytism as invo ...

, acceptance into a mission as a convert, in theory, required abandoning most, if not all, traditional lifeways." Various strategies of control were implemented to retain control, such as use of violence, segregation by age and gender, and using new converts as instruments of control over others. For example, Mission San Gabriel's Father Zalvidea punished suspected shamans "with frequent flogging and by chaining traditional religious practitioners together in pairs and sentencing them to hard labor in the sawmill." A missionary during this period reported that three out of four children died at Mission San Gabriel before reaching the age of 2. Nearly 6,000 Tongva lie buried in the grounds of the San Gabriel Mission. Carey McWilliams characterized it as follows: "the Franciscan padres eliminated Indians with the effectiveness of Nazis operating concentration camps...."

There is much evidence of Tongva resistance to the mission system. Many individuals returned to their village at time of death. Many converts retained their traditional practices in both domestic and spiritual contexts, despite the attempts by the padres and missionaries to control them. Traditional foods were incorporated into the mission diet and lithic and shell bead production and use persisted. More overt strategies of resistance such as refusal to enter the system, work slowdowns, abortion and infanticide of children resulting from rape, and fugitivism were also prevalent. Five major uprisings were recorded at Mission San Gabriel alone. Two late-eighteenth century rebellions against the mission system were led by Nicolás José, who was an early convert who had two social identities: "publicly participating in Catholic sacraments at the mission but privately committed to traditional dances, celebrations, and rituals." He participated in a failed attempt to kill the mission's priests in 1779 and organized eight foothill villages in a revolt in October 1785 with

There is much evidence of Tongva resistance to the mission system. Many individuals returned to their village at time of death. Many converts retained their traditional practices in both domestic and spiritual contexts, despite the attempts by the padres and missionaries to control them. Traditional foods were incorporated into the mission diet and lithic and shell bead production and use persisted. More overt strategies of resistance such as refusal to enter the system, work slowdowns, abortion and infanticide of children resulting from rape, and fugitivism were also prevalent. Five major uprisings were recorded at Mission San Gabriel alone. Two late-eighteenth century rebellions against the mission system were led by Nicolás José, who was an early convert who had two social identities: "publicly participating in Catholic sacraments at the mission but privately committed to traditional dances, celebrations, and rituals." He participated in a failed attempt to kill the mission's priests in 1779 and organized eight foothill villages in a revolt in October 1785 with Toypurina

Toypurina (1760–1799) was a Kizhhttps://gabrielenoindians.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Toypurina_Raeganletter_220909_154647_page-0001-1_220909_155854.pdf medicine woman from the Jachivit village. She is notable for her opposition to the c ...

, who further organized the villages, which "demonstrated a previously undocumented level of regional political unification both within and well beyond the mission." However, divided loyalties among the natives contributed to the failure of the 1785 attempt as well as mission soldiers being alerted of the attempt by converts or neophytes.

Toypurina, José and two other leaders of the rebellion, Chief Tomasajaquichi of Juvit village and a man named Alijivit, from nearby village of Jajamovit, were put on trial for the 1785 rebellion. At his trial, José stated that he participated because the ban at the mission on dances and ceremony instituted by the missionaries, and enforced by the governor of California in 1782, was intolerable as they prevented their mourning ceremonies. When questioned about the attack, Toypurina is famously quoted in as saying that she participated in the instigation because “he hated

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

the padres and all of you, for living here on my native soil, for trespassing upon the land of my forefathers and despoiling our tribal domains. … I came o the missionto inspire the dirty cowards to fight, and not to quail at the sight of Spanish sticks that spit fire and death, nor oretch at the evil smell of gunsmoke—and be done with you white invaders!’ This quote, from Thomas Workman Temple II's article “Toypurina the Witch and the Indian Uprising at San Gabriel” is arguably a mistranslation and embellishment of her actual testimony. According to the soldier who recorded her words, she stated simply that she ‘‘was angry with the Padres and the others of the Mission, because they had come to live and establish themselves in her land.’’ In June 1788, nearly three years later, their sentences arrived from Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley o ...

: Nicolás José was banned from San Gabriel and sentenced to six years of hard labor in irons at the most distant penitentiary in the region. Toypurina was banished from Mission San Gabriel and sent to the most distant Spanish mission.

Resistance to Spanish rule demonstrated how the Spanish Crown's claims to California were both insecure and contested. By the 1800s, San Gabriel was the richest in the entire colonial mission system, supplying cattle, sheep, goats, hogs, horses, mules, and other supplies for settlers and settlements throughout Alta California

Alta California ('Upper California'), also known as ('New California') among other names, was a province of New Spain, formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but ...

.

The mission functioned as a slave plantation. Latter-day ethnologist Hugo Reid reported, “Indian children were taken from their parents to be raised behind bars at the mission. They were allowed outside the locked dormitories only to attend to church business and their assigned chores. When they were old enough, boys and girls were put to work in the vast vineyards and orchards owned by the missions. Soldiers watched, ready to hunt down any who tried to escape.” Writing in 1852, Reid said he knew of Tongva who “had an ear lopped off or were branded on the lip for trying to get away.”

In 1810, the "Gabrieleño" labor population at the mission was recorded to be 1,201. It jumped to 1,636 in 1820 and then declined to 1,320 in 1830. Resistance to this system of forced labor continued into the early 19th century. In 1817, the San Gabriel Mission recorded that there were "473 Indian fugitives." In 1828, a German immigrant purchased the land on which the village of Yang-Na stood and evicted the entire community with the help of Mexican officials.

Mexican secularization and occupation (1834–1848)

The mission period ended in 1834 with secularization under Mexican rule. Some "Gabrieleño" absorbed into Mexican society as a result of secularization, which emancipated the neophytes. Tongva and other California Natives largely became workers while former Spanish elites were granted huge land grants. Land was systemically denied to California Natives by ''

The mission period ended in 1834 with secularization under Mexican rule. Some "Gabrieleño" absorbed into Mexican society as a result of secularization, which emancipated the neophytes. Tongva and other California Natives largely became workers while former Spanish elites were granted huge land grants. Land was systemically denied to California Natives by ''Californio

Californio (plural Californios) is a term used to designate a Hispanic Californian, especially those descended from Spanish and Mexican settlers of the 17th through 19th centuries. California's Spanish-speaking community has resided there sin ...

'' land owning men. In the Los Angeles basin area, only 20 former neophytes from San Gabriel Mission received any land from secularization. What they received were relatively small plots of land. A "Gabrieleño" by the name of Prospero Elias Dominguez was granted a 22-acre plot near the mission while Mexican authorities granted the remainder of the mission land, approximately 1.5 million acres, to a few colonist families. In 1846, it was noted by researcher Kelly Lytle Hernández that 140 Gabrieleños signed a petition demanding access to mission lands and that ''Californio'' authorities rejected their petition.

Emancipated from enslavement in the missions yet barred from their own land, most Tongva became landless refugees during this period. Entire villages fled inland to escape the invaders and continued devastation. Others moved to Los Angeles, a city which saw an increase in the Native population from 200 in 1820 to 553 in 1836 (out of a total population of 1,088). As stated by scholar Ralph Armbruster-Sandoval, "while they should have been owners, the Tongva became workers, performing strenuous, back-breaking labor just as they had done ever since settler colonialism emerged in Southern California." As described by researcher Heather Valdez Singleton, Los Angeles was heavily dependent on Native labor and "grew slowly on the back of the Gabrieleño laborers." Some of the people became ''vaquero

The ''vaquero'' (; pt, vaqueiro, , ) is a horse-mounted livestock herder of a tradition that has its roots in the Iberian Peninsula and extensively developed in Mexico from a methodology brought to Latin America from Spain. The vaquero became t ...

s'' on the ranches, highly skilled horsemen or cowboys, herding and caring for the cattle. There was little land available to the Tongva to use for food outside of the ranches. Some crops such as corn and beans were planted on ranchos to sustain the workers.

Several Gabrieleño families stayed within the San Gabriel township, which became "the cultural and geographic center of the Gabrieleño community." Yaanga also diversified and increased in size, with peoples of various Native backgrounds coming to live together shortly following secularization. However, the government had instituted a system dependent on Native labor and servitude and increasingly eliminated any alternatives within the Los Angeles area. As explained by Kelly Lytle Hernández, "there was no place for Natives living but not working in Mexican Los Angeles. In turn, the ''ayuntamiunto'' (city council) passed new laws to compel Natives to work or be arrested." In January 1836, the council directed ''Californios'' to sweep across Los Angeles to arrest "all drunken Indians." As recorded by Hernández, "Tongva men and women, along with an increasingly diverse set of their Native neighbors, filled the jail and convict labor crews in Mexican Los Angeles." By 1844, most Natives in Los Angeles worked as servants in a perpetual system of servitude, tending to the land and serving settlers, invaders, and colonizers.

The ''ayuntamiunto'' forced the Native settlement of Yaanga to move farther away from town. By the mid-1840s, the settlement was forcibly moved eastward across the Los Angeles River

, name_etymology =

, image = File:Los Angeles River from Fletcher Drive Bridge 2019.jpg

, image_caption = L.A. River from Fletcher Drive Bridge

, image_size = 300

, map = LARmap.jpg

, map_size ...

, placing a divide between Mexican Los Angeles and the nearest Native community. However, "Native men, women, and children continued to live (not just work) in the city. On Saturday Nights, they even held parties, danced, and gambled at the removed Yaanga village and also at the plaza at the center of town." In response, the ''Californios'' continued to attempt to control Native lives, issuing Alta California governor Pio Pico

Pio may refer to:

Places

* Pio Lake, Italy

* Pio Island, Solomon Islands

* Pio Point, Bird Island, south Atlantic Ocean

People

* Pio (given name)

* Pio (surname)

* Pio (footballer, born 1986), Brazilian footballer

* Pio (footballer, born 1 ...

a petition in 1846 stating: "We ask that the Indians be placed under strict police surveillance or the persons for whom the Indians work give he Indiansquarter at the employer's rancho." In 1847, a law was passed that prohibited Gabrielenos from entering the city without proof of employment. A part of the proclamation read:Indians who have no masters but are self-sustaining, shall be lodged outside of the City limits in localities widely separated... All vagrant Indians of either sex who have not tried to secure a situation within four days and are found unemployed, shall be put to work on public works or sent to the house of correction.In 1848, Los Angeles formally became a town of the United States following the

Mexican-American War

Mexican Americans ( es, mexicano-estadounidenses, , or ) are Americans of full or partial Mexican heritage. In 2019, Mexican Americans comprised 11.3% of the US population and 61.5% of all Hispanic and Latino Americans. In 2019, 71% of Mexica ...

.

American occupation and continued subjugation (1848–)

Landless and unrecognized, the people faced continued violence, subjugation, and enslavement (through convict labor) under American occupation. Some of the people were displaced to small Mexican and Native communities in the Eagle Rock and Highland Park districts of Los Angeles as well as Pauma,

Landless and unrecognized, the people faced continued violence, subjugation, and enslavement (through convict labor) under American occupation. Some of the people were displaced to small Mexican and Native communities in the Eagle Rock and Highland Park districts of Los Angeles as well as Pauma, Pala Pala may refer to:

Places

Chad

*Pala, Chad, the capital of the region of Mayo-Kebbi Ouest

Estonia

*Pala, Kose Parish, village in Kose Parish, Harju County

*Pala, Kuusalu Parish, village in Kuusalu Parish, Harju County

* Pala, Järva County, vil ...

, Temecula

Temecula (; es, Temécula, ; Luiseño: ''Temeekunga'') is a city in southwestern Riverside County, California, United States. The city had a population of 110,003 as of the 2020 census and was incorporated on December 1, 1989. The city is a ...

, Pechanga, and San Jacinto. Imprisonment of Natives in Los Angeles was a symbol of establishing the new "rule of law." The city's vigilante community would routinely "invade" the jail and hang the accused in the streets. Once congress granted statehood to California in 1850, many of the first laws passed targeted Natives for arrest, imprisonment, and convict labor. The 1850 Act for the Government and Protection of Indians "targeted Native peoples for easy arrest by stipulating that they could be arrested on vagrancy charges based 'on the complaint of any reasonable citizen'" and Gabrieleños faced the brunt of this policy. Section 14 of the act stated:When an Indian is convicted of any offence before a Justice of the Peace punishable by fine, any white person may, by consent of the Justice, give bond for said Indian, conditioned for the payment of said fine and costs, and in such case the Indian shall be compelled to work for the person so bailing, until he has discharged or cancelled the fine assessed against him.Native men were disproportionately criminalized and swept into this legalized system of

indentured servitude

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an " indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayme ...

. As was recorded by Anglo-American settlers, "'White men, whom the Marshal is too discreet to arrest' ... spilled out of the town's many saloons, streets, and brothels, but the aggressive and targeted enforcement of state and local vagrancy and drunk codes filled the Los Angeles County Jail with Natives, most of whom were men." Most spent their days working on the county chain gang

A chain gang or road gang is a group of prisoners chained together to perform menial or physically challenging work as a form of punishment. Such punishment might include repairing buildings, building roads, or clearing land. The system was not ...

, which was largely involved with keeping the city streets clean in the 1850s and 1860s but increasingly included road construction projects as well.

Although federal officials reported that there were an estimated 16,930 California Indians and 1,050 at Mission San Gabriel, "the federal agents ignored them and those living in Los Angeles" because they were viewed as "friendly to the whites," as revealed in the personal diaries of Commissioner Geroge W. Barbour. In 1852, superintendent of Indian affairs Edward Fitzgerald Beale

Edward Fitzgerald "Ned" Beale (February 4, 1822 – April 22, 1893) was a national figure in the 19th-century United States. He was a naval officer, military general, explorer, frontiersman, Indian affairs superintendent, California rancher, ...

echoed this sentiment, reporting that "because these Indians were Christians, with many holding ranch jobs and having interacted with whites," that "they are not much to be dreaded." Although a California Senate Bill of 2008 asserted that the US government signed treaties with the Gabrieleño, promising of land for reservations, and that these treaties were never ratified, a paper published in 1972 by Robert Heizer Robert Fleming Heizer (July 13, 1915 – July 18, 1979) was an archaeologist who conducted extensive fieldwork and reporting in California, the Southwestern United States, and the Great Basin.

Background

Robert Fleming Heizer was born July 13, 1 ...

of the University of California at Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public university, public land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of Californi ...

, shows that the eighteen treaties made between April 29, 1851, and August 22, 1852, were negotiated with persons who did not represent the Tongva people and that none of these persons had authority to cede lands that belonged to the people.

An 1852 editorial in the ''Los Angeles Star

''Los Angeles Star'' (''La Estrella de Los Angeles'') was the first newspaper in Los Angeles, California, U.S. The publication ran from 1851 to 1879.

History Early history and background

The first proposition to establish a newspaper in Los ...

'' revealed the public's anger towards any possibility of the Gabrieleño receiving recognition and exercising sovereignty:To place upon our most fertile soil the most degraded race of aborigines upon the North American Continent, to invest them with the rights of sovereignty, and to teach them that they are to be treated as powerful and independent nations, is planting the seeds of future disaster and ruin... We hope that the general government will let us alone—that it will neither undertake to feed, settle or remove the Indians amongst whome we in the South reside, and that they leave everything just as it now exists, except affording us the protection which two or three cavalry companies would give.In 1852, Hugo Reid wrote a series of letters for the ''

Los Angeles Star

''Los Angeles Star'' (''La Estrella de Los Angeles'') was the first newspaper in Los Angeles, California, U.S. The publication ran from 1851 to 1879.

History Early history and background

The first proposition to establish a newspaper in Los ...

'' from the center of the Gabrieleño community in San Gabriel township, describing Gabrieleño life and culture. Reid himself was married to a Gabrieleño woman by the name of Bartolomea Cumicrabit, who he renamed "Victoria." Reid wrote the following: "Their chiefs still exist. In San Gabriel remain only four, and those young... They have no jurisdiction more than to appoint times for holding of Feasts and regulating affairs connected with the church raditional structure made of brush" There is some speculation that Reid was campaigning for the position of Indian agent in Southern California, but died before he could be appointed. Instead, in 1852, Benjamin D. Wilson

Benjamin Davis Wilson (December 1, 1811 – March 11, 1878), commonly known as Don Benito Wilson,Excerpt: ''"Wilson, now known as Don Benito, became a Californio – that group of Mexicans and Angols who thought of themselves as Californians rathe ...

was appointed, who maintained the status quo. The letters of Hugo Reid revealed the names of 28 Gabrielino villages.

In 1855, the Gabrieleño were reported by the superintendent of Indian affairs Thomas J. Henley

Thomas Jefferson Henley (June 18, 1808 – May 1, 1875) was a U.S. Representative from Indiana, father of Barclay Henley.

Born in Richmond, Indiana, Henley attended Indiana University at Bloomington.

He studied law.

He was admitted to the ba ...

to be in "a miserable and degraded condition." However, Henley admitted that moving them to a reservation, potentially at Sebastian Reserve in Tejon Pass

The Tejon Pass , previously known as ''Portezuelo de Cortes'', ''Portezuela de Castac'', and Fort Tejon Pass is a mountain pass between the southwest end of the Tehachapi Mountains and northeastern San Emigdio Mountains, linking Southern Calif ...

, would be opposed by the citizens because "in the vineyards, especially during the grape season, their labor is made useful and is obtained at a cheap rate." A few Gabrieleño were in fact at Sebastian Reserve and maintained contact with the people living in San Gabriel during this time.

In 1859, amidst increasing criminalization

Criminalization or criminalisation, in criminology, is "the process by which behaviors and individuals are transformed into crime and criminals". Previously legal acts may be transformed into crimes by legislation or judicial decision. However, ...

and absorption into the city's burgeoning convict labor system, the county grand jury declared "stringent vagrant laws should be enacted and enforced compelling such persons Indians'to obtain an honest livelihood or seek their old homes in the mountains." This declaration ignored Reid's research, which stated that most Tongva villages, including Yaanga

Yaanga was a large Tongva (or Kizh) village originally located near what is now downtown Los Angeles, just west of the Los Angeles River and beneath U.S. Route 101. People from the village were recorded as ''Yabit'' in missionary records althou ...

, "were located in the basin, along its rivers and on its shoreline, stretching from the deserts and to the sea." Only a few villages led by ''tomyaars'' (chiefs) were "in the mountains, where Chengiichngech's avengers, serpents, and bears lived," as described by historian Kelly Lytle Hernández. However, "the grand jury dismissed the depths of Indigenous claims to life, land, and sovereignty in the region and, instead, chose to frame Indigenous peoples as drunks and vagrants loitering

Loitering is the act of remaining in a particular public place for a prolonged amount of time without any apparent purpose.

While the laws regarding loitering have been challenged and changed over time, loitering is still illegal in various j ...

in Los Angeles... disavowing a long history of Indigenous belonging in the basin."

While in 1848, Los Angeles had been a small town largely of Mexicans and Natives, by 1880 it was home to an Anglo-American majority following waves of white migration in the 1870s from the completion of the transcontinental railroad

A transcontinental railroad or transcontinental railway is contiguous railroad trackage, that crosses a continental land mass and has terminals at different oceans or continental borders. Such networks can be via the tracks of either a single ...

. As stated by research Heather Valdez Singleton, newcomers "took advantage of the fact that many Gabrieleño families, who had cultivated and lived on the same land for generations, did not hold legal title to the land, and used the law to evict

Eviction is the removal of a tenant from rental property by the landlord. In some jurisdictions it may also involve the removal of persons from premises that were foreclosed by a mortgagee (often, the prior owners who defaulted on a mortgag ...

Indian families." The Gabrieleño became vocal about this and notified former Indian agent J. Q. Stanley, who referred to them as "half-civilized" yet lobbied to protect the Gabrieleño "against the lawless whites living amongst them," arguing that they would become "vagabonds

Vagrancy is the condition of homelessness without regular employment or income. Vagrants (also known as bums, vagabonds, rogues, tramps or drifters) usually live in poverty and support themselves by begging, scavenging, petty theft, tempora ...

" otherwise. However, active Indian agent Augustus P. Greene's recommendation took precedent, arguing that "Mission Indians in southern California were slowing the settlement of this portion of the country for non-Indians and suggested that the Indians be completely assimilated," as summarized by Singleton.

In 1882, Helen Hunt Jackson

Helen Hunt Jackson (pen name, H.H.; born Helen Maria Fiske; October 15, 1830 – August 12, 1885) was an American poet and writer who became an activist on behalf of improved treatment of Native Americans by the United States government. She de ...

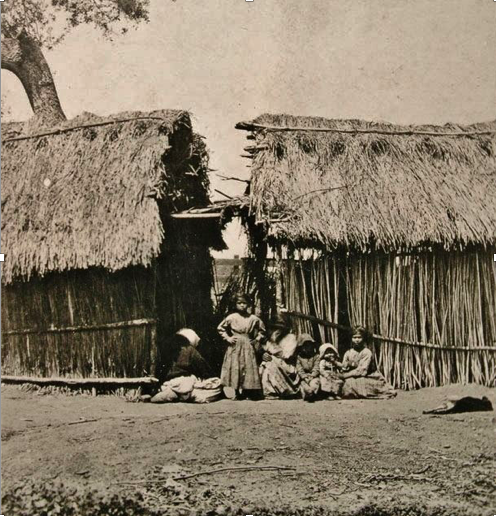

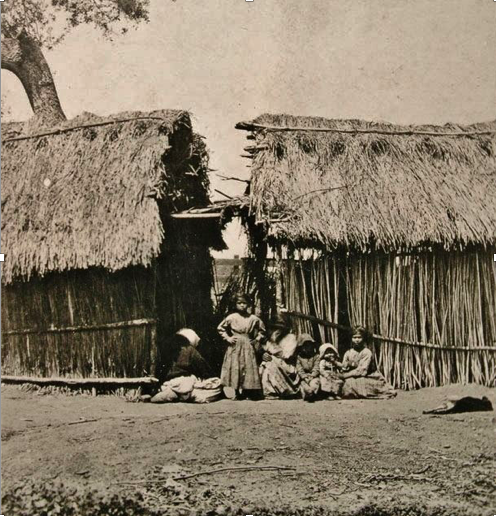

was sent by the federal government to document the condition of the Mission Indians in southern California. She reported that there were a considerable number of people "in the colonies in the San Gabriel Valley, where they live like gypsies in brush huts, here today, gone tomorrow, eking out a miserable existence by days' work." However, even though Jackson's report would become the impetus for the Mission Indian Relief Act of 1891, the Gabrieleño were "overlooked by the commission charged with setting aside lands for Mission Indians." It is speculated that this may have been attributed to what was perceived as their compliance with the government, which caused them to be neglected, as noted earlier by Indian agent J. Q. Stanley.

Extinction myth

By the early twentieth century, Gabrieleño identity had suffered greatly under American occupation. Most Gabrieleño publicly identified as Mexican, learned Spanish, and adopted Catholicism while keeping their identity a secret. In schools, students were punished for mentioning that they were "Indian" and many of the people assimilated into

By the early twentieth century, Gabrieleño identity had suffered greatly under American occupation. Most Gabrieleño publicly identified as Mexican, learned Spanish, and adopted Catholicism while keeping their identity a secret. In schools, students were punished for mentioning that they were "Indian" and many of the people assimilated into Mexican-American

Mexican Americans ( es, mexicano-estadounidenses, , or ) are Americans of full or partial Mexican heritage. In 2019, Mexican Americans comprised 11.3% of the US population and 61.5% of all Hispanic and Latino Americans. In 2019, 71% of Mexica ...

or Chicano

Chicano or Chicana is a chosen identity for many Mexican Americans in the United States. The label ''Chicano'' is sometimes used interchangeably with ''Mexican American'', although the terms have different meanings. While Mexican-American ident ...

culture. Further attempts to establish a reservation for the Gabrieleño in 1907 failed. Soon it began to be perpetuated in the local press that the Gabrieleño were extinct. In February 1921, the ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' (abbreviated as ''LA Times'') is a daily newspaper that started publishing in Los Angeles in 1881. Based in the LA-adjacent suburb of El Segundo since 2018, it is the sixth-largest newspaper by circulation in the ...

'' declared that the death of Jose de los Santos Juncos, an Indigenous man who lived at Mission San Gabriel and was 106 years old at his time of passing, "marked the passing of a vanished race." In 1925, Alfred Kroeber

Alfred Louis Kroeber (June 11, 1876 – October 5, 1960) was an American cultural anthropologist. He received his PhD under Franz Boas at Columbia University in 1901, the first doctorate in anthropology awarded by Columbia. He was also the first ...

declared that the Gabrieleño culture was extinct, stating "they have melted away so completely that we know more of the finer facts of the culture of ruder tribes." Scholars have noted that this extinction myth has proven to be "remarkably resilient," yet is untrue.

Despite being declared extinct, Gabrieleño children were still being assimilated by federal agents who encouraged enrollment at Sherman Indian School

Sherman Indian High School (SIHS) is an off-reservation boarding high school for Native Americans. Originally opened in 1892 as the Perris Indian School, in Perris, California, the school was relocated to Riverside, California in 1903, under the n ...

in Riverside, California

Riverside is a city in and the county seat of Riverside County, California, United States, in the Inland Empire metropolitan area. It is named for its location beside the Santa Ana River. It is the most populous city in the Inland Empire an ...

. Between 1890 and 1920, at least 50 Gabrieleño children were recorded at the school. Between 1910 and 1920, the establishment of the Mission Indian Federation, of which the Gabrieleño joined, led to the 1928 California Indians Jurisdictional Act, which created official enrollment records for those who could prove ancestry from a California Indian living in the state in 1852. Over 150 people self-identified as Gabrieleño on this roll. A Gabrieleño woman at Tejon Reservation provided the names and addresses of several Gabrieleño living in San Gabriel, showing that contact between the group at Tejon Reservation and the group at San Gabriel township, which are more than 70 miles apart, was being maintained into the 1920s and 1930s.

In 1971, Bernice Johnston, former curator of the Southwest Museum

The Southwest Museum of the American Indian is a museum, library, and archive located in the Mt. Washington neighborhood of Los Angeles, California, above the north-western bank of the Arroyo Seco (Los Angeles County) canyon and stream. The muse ...

and author of ''California’s Gabrieleno Indians'' (1962), spoke to the ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' (abbreviated as ''LA Times'') is a daily newspaper that started publishing in Los Angeles in 1881. Based in the LA-adjacent suburb of El Segundo since 2018, it is the sixth-largest newspaper by circulation in the ...

'': “After spending much of her life trying to trace the Indians, she believes she almost came in contact with some Gabrielenos a few years ago…She relates that on a Sunday, while giving a tour of the museum, ‘I saw these shy, dark people looking around. They were asking questions about the Gabrieleno Indians. I asked why they wanted to know, and nearly fell over when they told me they were Gabrielenos and wanted to know something about themselves. I was busy with the tour, we were crowded. I rushed back to them as soon as I could but they were gone. I didn’t even get their names.”Vasquez, Richard. "Gabrieleno Indians--This Land Was Their Land: Land Conflicts." ''Los Angeles Times'', June 14, 1971, pp. 2-b1''.''

Lacking federal recognition

The continued denigration and denial of Gabrieleño identity perpetuated by Anglo-American institutions such as schools and museums has presented numerous obstacles for the people throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Contemporary members have cited being denied the legitimacy of their identity. Tribal identity is also heavily hindered by a lack of federal recognition and having no land base.

Being denied federal recognition has prevented the Tongva from protecting their sacred sites, ancestral remains, and artifacts which have faced continued destruction in the 21st century. In 2001, a 9,000-year-old

The continued denigration and denial of Gabrieleño identity perpetuated by Anglo-American institutions such as schools and museums has presented numerous obstacles for the people throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Contemporary members have cited being denied the legitimacy of their identity. Tribal identity is also heavily hindered by a lack of federal recognition and having no land base.

Being denied federal recognition has prevented the Tongva from protecting their sacred sites, ancestral remains, and artifacts which have faced continued destruction in the 21st century. In 2001, a 9,000-year-old Bolsa Chica

Bolsa Chica State Ecological Reserve is a natural reserve and public land in Orange County, governed by the state of California, and immediately adjacent to the city of Huntington Beach, California. The reserve is designated by the Californi ...

village site was heavily damaged in favor of commercial development. Over ten years later, the company which performed the initial archaeological survey was fined $600,000 for its poor assessment in favor of commercial development.

Human remains near the village of Genga, a shared village site of the Tongva and Acjachemen

The Acjachemen (, alternate spelling: Acagchemem) are an Indigenous people of California. They historically lived south of what is known as Aliso Creek and north of the Las Pulgas Canyon in what are now the southern areas of Orange County and ...

, were unearthed and moved in the 2010s, despite opposition from the tribes, in favor of commercial development. In 2019, California State University, Long Beach

California State University, Long Beach (CSULB) is a public research university in Long Beach, California. The 322-acre campus is the second largest of the 23-school California State University system (CSU) and one of the largest universities ...

dumped trash and dirt on top of the village site of Puvunga

Puvunga (alternate spellings: Puvungna or Povuu'nga) is an ancient village and sacred site of the Tongva nation, the Indigenous people of the Los Angeles Basin, and the Acjachemen, the Indigenous people of Orange County now located at California ...

in its construction of new student housing. In 2022, part of the village area of Genga may be transformed into a green space. Leaders of the project have claimed that "tribal descendants of the area’s earliest residents will also have a voice" in how the park is developed.

Culture

The Tongva lived in the main part of the most fertile lowland of southern California, including a stretch of sheltered coast with a pleasant climate and abundant food resources, and the most habitable of the Santa Barbara Islands. They have been referred to as the most culturally 'advanced' group south of the Tehachapi, and the wealthiest of the

The Tongva lived in the main part of the most fertile lowland of southern California, including a stretch of sheltered coast with a pleasant climate and abundant food resources, and the most habitable of the Santa Barbara Islands. They have been referred to as the most culturally 'advanced' group south of the Tehachapi, and the wealthiest of the Uto-Aztecan

Uto-Aztecan, Uto-Aztekan or (rarely in English) Uto-Nahuatl is a family of indigenous languages of the Americas, consisting of over thirty languages. Uto-Aztecan languages are found almost entirely in the Western United States and Mexico. The na ...

speakers in California, dominating other native groups culturally wherever contacts occurred. Many of the cultural developments of the surrounding southern peoples had their origin with the Gabrieleño. The Tongva territory was the center of a flourishing trade network that extended from the Channel Islands

The Channel Islands ( nrf, Îles d'la Manche; french: îles Anglo-Normandes or ''îles de la Manche'') are an archipelago in the English Channel, off the French coast of Normandy. They include two Crown Dependencies: the Bailiwick of Jersey, ...

in the west to the Colorado River

The Colorado River ( es, Río Colorado) is one of the principal rivers (along with the Rio Grande) in the Southwestern United States and northern Mexico. The river drains an expansive, arid watershed that encompasses parts of seven U.S. s ...

in the east, allowing the people to maintain trade relations with the Cahuilla

The Cahuilla , also known as ʔívil̃uqaletem or Ivilyuqaletem, are a Native American people of the various tribes of the Cahuilla Nation, living in the inland areas of southern California.Serrano,

The Tongva had a concentrated population along the coast. They fished and hunted in the estuary of the Los Angeles River, and like the

The Tongva had a concentrated population along the coast. They fished and hunted in the estuary of the Los Angeles River, and like the

In the Tongva economic system, food resources were managed by the village chief, who was given a portion of the yield of each day's hunting, fishing, or gathering to add to the communal food reserves. Individual families stored some food to be used in times of scarcity. Villages were located in places with accessible drinking water, protection from the elements, and productive areas where different

In the Tongva economic system, food resources were managed by the village chief, who was given a portion of the yield of each day's hunting, fishing, or gathering to add to the communal food reserves. Individual families stored some food to be used in times of scarcity. Villages were located in places with accessible drinking water, protection from the elements, and productive areas where different

"Two new names in the solar system: Herse and Weywot"

, ''The Planetary Society.'' 12 Nov 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2012. Weywot ruled over the Tongva, but he was very cruel, and he was finally killed by his own sons. When the Tongva assembled to decide what to do next, they had a vision of a ghostly being who called himself Quaoar, who said he had come to restore order and to give laws to the people. After he had given instructions as to which groups would have political and spiritual leadership, he began to dance and slowly ascended into heaven. After consulting with the Tongva, astronomers

From the Spanish colonial period, Tongva place names have been absorbed into general use in Southern California. Examples include

From the Spanish colonial period, Tongva place names have been absorbed into general use in Southern California. Examples include

Reid, Hugo. (1852), ''The Indians of Los Angeles County''

, full text available online at Library of Congress * Johnson, J. R

''Ethnohistory of West S.F. Valley''

CA State Parks, 2006 * Johnston, Bernice Eastman. 1962

''California's Gabrielino Indians''

. Southwest Museum, Los Angeles. * * McCawley, William. 1996. ''The First Angelinos: The Gabrielino Indians of Los Angeles.'' Malki Museum Press, Banning, California. * Williams, Jack S., ''The Tongva of California'', Library of Native Americans of California, The Rosen Publishing Group, 2003, .

Gabrieleno (Tongva) Band of Mission Indians

(state-recognized)

Gabrielino / Tongva Nation

Gabrielino-Tongva Indian Tribe

;Other

at UCLA.

Antelope Valley Indian Museum

online collections database; use 'search' to see many Tongva artifacts.

Tongva Exhibit, Heritage Park

Santa Fe Springs, California

Gabrieleño-Tongva Mission Indians

KCET {{DEFAULTSORT:Tongva people Tongva, California Mission Indians Native American tribes in California History of Los Angeles History of Los Angeles County, California History of Orange County, California San Gabriel, California Unrecognized tribes in the United States

Luiseño

The Luiseño or Payómkawichum are an indigenous people of California who, at the time of the first contacts with the Spanish in the 16th century, inhabited the coastal area of southern California, ranging from the present-day southern part of ...

, Chumash Chumash may refer to:

*Chumash (Judaism), a Hebrew word for the Pentateuch, used in Judaism

*Chumash people, a Native American people of southern California

*Chumashan languages, indigenous languages of California

See also

*Chumash traditional n ...

, and Mohave.

Like all Indigenous peoples, they utilized and existed in an interconnected relationship with the flora

Flora is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring ( indigenous) native plants. Sometimes bacteria and fungi are also referred to as flora, as in the terms '' gut flora'' or '' skin flora''.

...

and fauna

Fauna is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding term for plants is '' flora'', and for fungi, it is '' funga''. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively referred to as '' biota''. ...

of their familial territory. Villages were located throughout four major ecological zones, as noted by biologist Matthew Teutimez: interior mountains and foothills, grassland/oak woodland, sheltered coastal canyons, and the exposed coast. Therefore, resources such as plants, animals, and earth minerals were diverse and used for various purposes, including for food and materials. Prominent flora included oak (''Quercus agrifolia

''Quercus agrifolia'', the California live oak, or coast live oak, is a highly variable, often evergreen oak tree, a type of live oak, native to the California Floristic Province. It may be shrubby, depending on age and growing location, but is ...

'') and willow ('' Salix spp.'') trees, chia (''Salvia columbariae

''Salvia columbariae'' is an annual plant that is commonly called chia, chia sage, golden chia, or desert chia, because its seeds are used in the same way as those of ''Salvia hispanica'' ( chia). It grows in California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, N ...

''), cattail ('' Typha spp.''), datura or jimsonweed (''Datura innoxia

''Datura innoxia'' (often spelled ''inoxia''), known as pricklyburr, recurved thorn-apple, downy thorn-apple, Indian-apple, lovache, moonflower, nacazcul, toloatzin, toloaxihuitl, tolguache or toloache, is a species of flowering plant in the fami ...

''), white sage (''Salvia apiana

''Salvia apiana'', the white sage, bee sage, or sacred sage is an evergreen perennial shrub that is native to the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico, found mainly in the coastal sage scrub habitat of Southern California and Baja C ...

''), '' Juncus spp.'', Mexican Elderberry (''Sambucus