Timeline of Russian innovation on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

This timeline of Russian Innovation encompasses key events in the

This timeline of Russian Innovation encompasses key events in the

;

; ; Multidomed church

: The multidomed church is a typical form of Russian church architecture, which distinguishes Russia from other Eastern Orthodox nations and Christian denominations. Indeed, the earliest Russian churches built just after the

; Multidomed church

: The multidomed church is a typical form of Russian church architecture, which distinguishes Russia from other Eastern Orthodox nations and Christian denominations. Indeed, the earliest Russian churches built just after the  ; Kissel

: ''Kissel'' or ''kisel'' is a dessert that consists of sweetened juice, typically that of berries, thickened with

; Kissel

: ''Kissel'' or ''kisel'' is a dessert that consists of sweetened juice, typically that of berries, thickened with

; Birch bark document

: A birch bark document is a document written on pieces of

; Birch bark document

: A birch bark document is a document written on pieces of  ;

; ; Gudok

: The gudok is an ancient East Slavic string

; Gudok

: The gudok is an ancient East Slavic string  ;1048

;1048

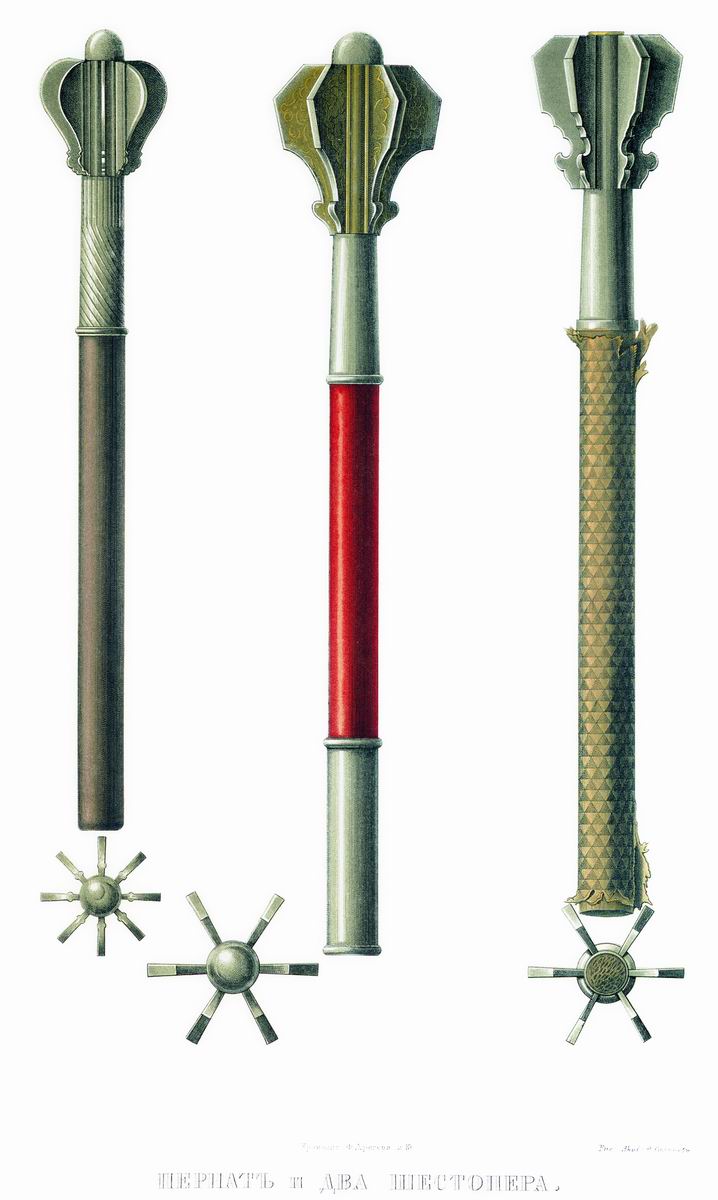

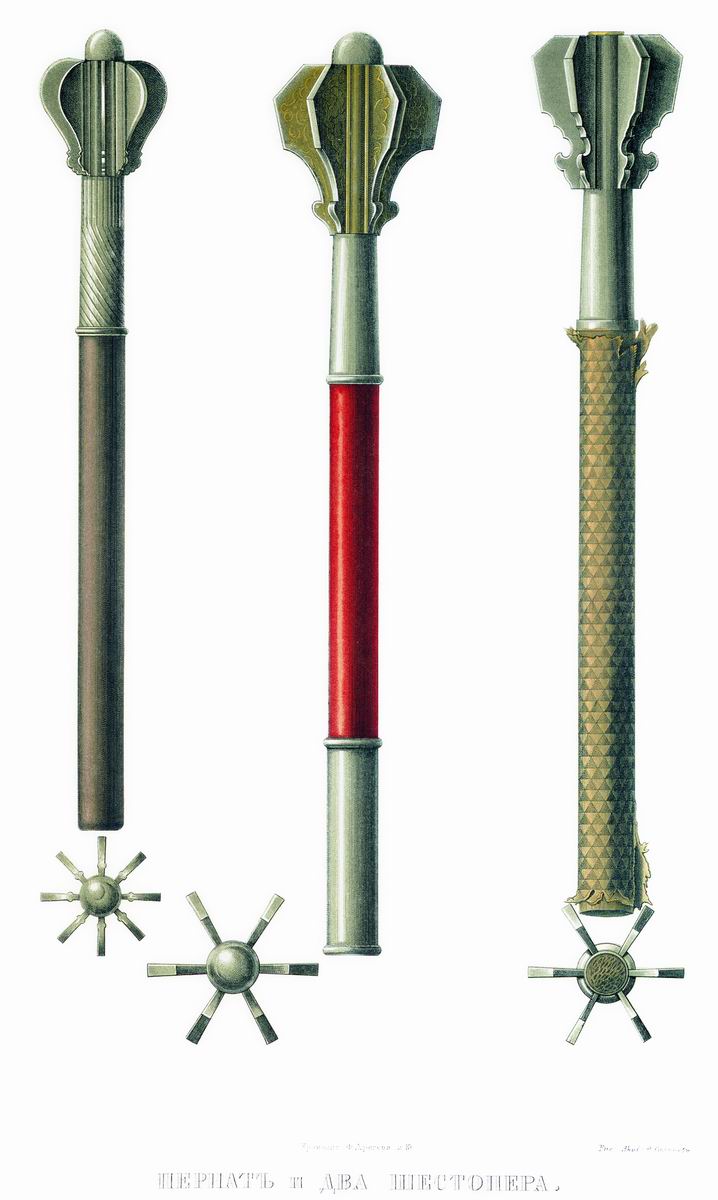

; Pernach

: The ''pernach'' is a type of flanged mace developed since the 12th century in the region of

; Pernach

: The ''pernach'' is a type of flanged mace developed since the 12th century in the region of  ;

;

;

; ; Onion dome

: The onion dome is a

; Onion dome

: The onion dome is a

* The Russian oven or Russian stove is a unique type of

* The Russian oven or Russian stove is a unique type of  c. 1430

c. 1430

Kokoshnik (architecture)

* The kokoshnik is a semicircular or keel-like exterior decorative element in the traditional

Kokoshnik (architecture)

* The kokoshnik is a semicircular or keel-like exterior decorative element in the traditional  1510s Tented roof masonry

* The tented roof masonry was a technique widely used in the

1510s Tented roof masonry

* The tented roof masonry was a technique widely used in the

Russian abacus

* The Russian abacus or schoty (literally "counts") is a

Russian abacus

* The Russian abacus or schoty (literally "counts") is a  1561 ''

1561 '' 1586 ''

1586 ''

Bird of Happiness

* The Bird of Happiness is the traditional North Russian wooden

Bird of Happiness

* The Bird of Happiness is the traditional North Russian wooden

* Khokhloma is the name of a Russian wood painting

* Khokhloma is the name of a Russian wood painting  1685 Tula pryanik

* The Tula pryanik is a type of printed

1685 Tula pryanik

* The Tula pryanik is a type of printed  * The balalaika is a

* The balalaika is a  Glass-holder

*The podstakannik (Russian: подстаканник, literally "thing under the glass"), or tea glass holder, is a holder with a handle, most commonly made of metal, that holds a drinking glass. The primary purpose of podstakanniki (pl.) is to hold a very hot glass of tea, which is usually consumed right after it is brewed. It is a traditional way of serving and drinking tea in Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and other post-Soviet states.

1693

*

Glass-holder

*The podstakannik (Russian: подстаканник, literally "thing under the glass"), or tea glass holder, is a holder with a handle, most commonly made of metal, that holds a drinking glass. The primary purpose of podstakanniki (pl.) is to hold a very hot glass of tea, which is usually consumed right after it is brewed. It is a traditional way of serving and drinking tea in Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and other post-Soviet states.

1693

*

1704

1704  * The yacht club is a sports

* The yacht club is a sports

1725

1725

1732

1732  1735 ''

1735 '' 1739

1739

File:Thunder Stone.jpg, ''The Transportation of the Thunder-stone in the Presence of

File:Орловский рысак.jpg, Orlov Trotter, considered the fastest for most of the 19th century.

File:Seven-string-guitar.jpg, A seven-string Russian guitar

File:315 Changes in uniforms and armament of troops of the Russian Imperial army.jpg, Russian soldiers wearing in

File:Lichtbogen 3000 Volt.jpg,

File:Russian sailor cap.jpg, Russian Navy's

File:Homeoscope03.gif, The search of data on

File:102 329 nobel oilwells.jpg, 19th-century

File:Household radiator.jpg, An old-style household radiator.

File:Saint Isaac's Cathedral.jpg,

File:Russian Olivier salad.jpg,

File:Гимнастёрка и карабин.jpg, Gymnasterka of sergeant of Red Army (1935)

File:Odner-arithmometer.jpg, W. T. Odhner's arithmometer

File:Yablochkov candles illuminating Music hall on la Place du Chateau d'eau ca 1880.jpg, Yablochkov candles illuminating a music hall in

File:Tramway-LVS-2005.JPG, Electric tram in

File:First matryoshka museum doll open.jpg, The original matryoshka carved by Vasily Zvyozdochkin and painted by Sergey Malyutin.

File:Tensile Steel Lattice Shell of Oval Pavilion by Vladimir Shukhov 1895.jpg, The world's first tensile steel

at p-lab.org 1903 Theoretical foundations of spaceflight * By

File:USCG AFFF.JPG, A modern foam fire extinguisher.

File:Sphygmomanometer.jpg, Aneroid

File:Gleb Kotelnikov.jpg, Gleb Kotelnikov with his invention, the knapsack parachute.

File:The Russian two-wheel car in London. 1914.jpg, Shilovsky's gyrocar in 1914, presented in

File:Ushanka of Soldier of Soviet Army-6.jpg, The later version of the Soviet Army ushanka.

File:Lydia kavina.jpg, Lydia Kavina playing theremin.

File:PalekhTroikaWolves.jpg,

File:Camalot number 6.JPG, Spring-loaded camming device in a parallel crack.

File:MC-3 pressure suit front.JPG, Pressure suit.

File:Underwater welding.jpg, A modern underwater welding.

File:ANT-20.jpg, ''Tupolev ANT-20'' propaganda aircraft.

File:Кирзовые_сапоги_российского_солдата.jpg, Kirza boots.

File:Kirl66 g.png, Kirlian photography, Kirlian photo of two coins.

File:Char T-34.jpg, T-34, the most successful tank design of

File:Berkovich.jpg, A Berkovich tip.

File:FlyingThroughNanotube.png, Inside a carbon nanotube.

File:Ilizarov2.jpg, An Ilizarov apparatus treating a fractured tibia and fibula.

File:Shevchenko BN350.gif, BN350 nuclear fast reactor.

File:Tokamak fields lg.png, Tokamak magnetic field and plasma (physics), plasma current.

File:Baikonur Cosmodrome Soyuz launch pad.jpg, Baikonur Cosmodrome's "Gagarin's Start" Soyuz (rocket family), Soyuz launch pad prior to the rollout of Soyuz TMA-13, October 10, 2008.

File:Semyorka Rocket R7 by Sergei Korolyov in VDNH Ostankino RAF0540.jpg, The large-size model of R-7 Semyorka, the first

File:RPG-7 detached.jpg, tAn RPG-7 with warhead, world's most used anti-tank weapon.

File:Vostok spacecraft.jpg, The model of Vostok program, Vostok spacecraft, the first human spaceflight module.

File:Russian space food.jpg, Russian space food.

File:Tsar Bomba Revised.jpg, A

File:RK2.png, Schematic diagram of the radial keratotomy with incisions shown.

File:Russian stationary plasma thrusters.jpg, Hall effect thrusters.

File:Shevchenko BN350 desalinati.jpg, BN-350 reactor, BN350 desalination unit, the first nuclear-heated desalination unit in the world.

File:APS underwater rifle REMOV.jpg, APS underwater assault rifle.

File:Russian Nuclear Icebreaker Arktika.jpg, Arktika (1972 nuclear icebreaker), NS ''Arktika'', the first surface ship to reach the North Pole.

File:Moscow Parad 2008 Ballist.jpg, RT-2PM Topol, the first reliable mobile

File:Typhoon iced.jpg, Typhoon-class submarine, covered with ice.

File:Tetrominoes IJLO STZ Worlds.svg, Tetris figures.

File:Mir on 12 June 1998edit1.jpg, Mir space station.

File:Su-27 Cobra 2b.png, A Su-27 performing the Cobra maneuver.

File:Beriew Be-200 at MAKS-2009.jpg, Beriev Be-200 dropping the water painted into the colors of the flag of Russia.

File:Sea Launch 01.jpg, A launch of Zenit 3SL rocket from the Sea Launch platform ''Ocean Odyssey'', originally built in Japan as oil platform, and then modified by Norway and

File:50 Let Pobedy.jpg, NS 50 Let Pobedy, the world's largest

history of technology

The history of technology is the history of the invention of tools and techniques and is one of the categories of world history. Technology can refer to methods ranging from as simple as stone tools to the complex genetic engineering and inf ...

in Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

, from the Grand Duchy of Moscow

The Grand Duchy of Moscow, Muscovite Russia, Muscovite Rus' or Grand Principality of Moscow (russian: Великое княжество Московское, Velikoye knyazhestvo Moskovskoye; also known in English simply as Muscovy from the Lati ...

up to the Russian Federation

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

.

The entries in this timeline fall into the following categories:

* indigenous inventions, like airliner

An airliner is a type of aircraft for transporting passengers and air cargo. Such aircraft are most often operated by airlines. Although the definition of an airliner can vary from country to country, an airliner is typically defined as an ai ...

s, AC transformers, radio receiver

In radio communications, a radio receiver, also known as a receiver, a wireless, or simply a radio, is an electronic device that receives radio waves and converts the information carried by them to a usable form. It is used with an antenna. Th ...

s, television

Television, sometimes shortened to TV, is a telecommunication medium for transmitting moving images and sound. The term can refer to a television set, or the medium of television transmission. Television is a mass medium for advertising, ...

, artificial satellite

A satellite or artificial satellite is an object intentionally placed into orbit in outer space. Except for passive satellites, most satellites have an electricity generation system for equipment on board, such as solar panels or radioiso ...

s, ICBM

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more thermonuclear warheads). Conventional, chemical, and biological weapons ...

s

* uniquely Russian products, objects and events, like Saint Basil's Cathedral

The Cathedral of Vasily the Blessed ( rus, Собо́р Васи́лия Блаже́нного, Sobór Vasíliya Blazhénnogo), commonly known as Saint Basil's Cathedral, is an Orthodox church in Red Square of Moscow, and is one of the most p ...

, Matryoshka doll

Matryoshka dolls ( ; rus, матрёшка, p=mɐˈtrʲɵʂkə, a=Ru-матрёшка.ogg), also known as stacking dolls, nesting dolls, Russian tea dolls, or Russian dolls, are a set of wooden dolls of decreasing size placed one inside ano ...

s, Russian vodka

Vodka ( pl, wódka , russian: водка , sv, vodka ) is a clear distilled alcoholic beverage. Different varieties originated in Poland, Russia, and Sweden. Vodka is composed mainly of water and ethanol but sometimes with traces of impuritie ...

* products and objects with superlative characteristics, like the Tsar Bomba

The Tsar Bomba () ( code name: ''Ivan'' or ''Vanya''), also known by the alphanumerical designation "AN602", was a thermonuclear aerial bomb, and the most powerful nuclear weapon ever created and tested. Overall, the Soviet physicist Andrei ...

, the AK-47

The AK-47, officially known as the ''Avtomat Kalashnikova'' (; also known as the Kalashnikov or just AK), is a gas-operated assault rifle that is chambered for the 7.62×39mm cartridge. Developed in the Soviet Union by Russian small-arms d ...

, and the Typhoon-class submarine

* scientific and medical discoveries, like the periodic law

Periodic trends are specific patterns that are present in the periodic table that illustrate different aspects of a certain element. They were discovered by the Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev in the year 1863. Major periodic trends include atom ...

, vitamins

A vitamin is an organic molecule (or a set of molecules closely related chemically, i.e. vitamers) that is an essential micronutrient that an organism needs in small quantities for the proper functioning of its metabolism. Essential nutrie ...

and stem cells

In multicellular organisms, stem cells are undifferentiated or partially differentiated cells that can differentiate into various types of cells and proliferate indefinitely to produce more of the same stem cell. They are the earliest type of ...

This timeline includes scientific and medical discoveries, products and technologies introduced by various peoples of Russia and its predecessor states, regardless of ethnicity, and also lists inventions by naturalized immigrant citizens. Certain innovations achieved internationally may also appear in this timeline in cases where the Russian side played a major role in such projects.

Kievan Rus'

10th century

;Architecture :The earliest Kievan churches were built and decorated with frescoes and mosaics by Byzantine masters. The great churches of Kievan Rus', built after the adoption of Christianity in 988, were the first examples of monumental architecture in the East Slavic lands. Early Eastern Orthodox churches were mainly made of wood, while major cathedrals often featured scores of small domes. The 10th-centuryChurch of the Tithes

The Church of the Tithes or Church of the Dormition of the Virgin ( uk, Десятинна Церква, ) was the first stone church in Kyiv.Mariya Lesiv, ''The Return of Ancestral Gods: Modern Ukrainian Paganism as an Alternative Vision for a ...

in Kiev was the first to be made of stone. ;

;Kokoshnik

The kokoshnik ( rus, коко́шник, p=kɐˈkoʂnʲɪk) is a traditional Russian headdress worn by women and girls to accompany the sarafan. The kokoshnik tradition has existed since the 10th century in the ancient Russian city Veliky No ...

: The kokoshnik is a traditional Russian head-dress for women. It is patterned to match the style of the sarafan

A sarafan ( rus, сарафа́н, p=sərɐˈfan, from fa, سراپا ''sarāpā'', literally " romhead to feet") is a long, trapezoidal Russian jumper dress (pinafore dress) worn by girls and women and forming part of Russian traditional fo ...

and can be pointed or round. It is tied at the back of the head with long thick ribbons in a large bow. The forehead is sometimes decorated with pearls or other jewelry. The word ''kokoshnik'' appeared in the 16th century, however the earliest head-dress pieces of a similar type were found in the 10th to 12th century burials in Veliky Novgorod

Veliky Novgorod ( rus, links=no, Великий Новгород, t=Great Newtown, p=vʲɪˈlʲikʲɪj ˈnovɡərət), also known as just Novgorod (), is the largest city and administrative centre of Novgorod Oblast, Russia. It is one of the ...

. It was worn by girls and women on special occasions until the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

, and was subsequently introduced into Western fashion

Fashion is a form of self-expression and autonomy at a particular period and place and in a specific context, of clothing, footwear, lifestyle, accessories, makeup, hairstyle, and body posture. The term implies a look defined by the fash ...

by Russian émigré

An ''émigré'' () is a person who has emigrated, often with a connotation of political or social self-exile. The word is the past participle of the French ''émigrer'', "to emigrate".

French Huguenots

Many French Huguenots fled France followin ...

s.

;Kvass

Kvass is a fermented cereal-based low alcoholic beverage with a slightly cloudy appearance, light-brown colour and sweet-sour taste. It may be flavoured with berries, fruits, herbs or honey.

Kvass stems from the northeastern part of Europe, ...

/ Okroshka

Okróshka (russian: окро́шка) is a cold soup of Russian origin and probably originated in the Volga region.

The classic soup is a mix of mostly raw vegetables (like cucumbers, radishes and spring onions), boiled potatoes, eggs, cooked ...

: ''Kvass'' or ''kvas'', sometimes called in English a "bread drink", is a fermented

Fermentation is a metabolic process that produces chemical changes in organic substrates through the action of enzymes. In biochemistry, it is narrowly defined as the extraction of energy from carbohydrates in the absence of oxygen. In food p ...

beverage made from black rye or rye bread

Bread is a staple food prepared from a dough of flour (usually wheat) and water, usually by baking. Throughout recorded history and around the world, it has been an important part of many cultures' diet. It is one of the oldest human-made f ...

, which contributes to its light or dark colour. By the content of alcohol

Alcohol most commonly refers to:

* Alcohol (chemistry), an organic compound in which a hydroxyl group is bound to a carbon atom

* Alcohol (drug), an intoxicant found in alcoholic drinks

Alcohol may also refer to:

Chemicals

* Ethanol, one of sev ...

resulted from fermentation, it is classified as non-alcoholic: up to 1.2% of alcohol, which is so low that it is considered acceptable for consumption by children. While the early low-alcoholic prototypes of kvass were known in some ancient civilizations, its modern, almost non-alcoholic form originated in Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

. Kvass was first mentioned in the Russian Primary Chronicle

The ''Tale of Bygone Years'' ( orv, Повѣсть времѧньныхъ лѣтъ, translit=Pověstĭ vremęnĭnyxŭ lětŭ; ; ; ; ), often known in English as the ''Rus' Primary Chronicle'', the ''Russian Primary Chronicle'', or simply the ...

, which tells how Prince Vladimir the Great

Vladimir I Sviatoslavich or Volodymyr I Sviatoslavych ( orv, Володимѣръ Свѧтославичь, ''Volodiměrъ Svętoslavičь'';, ''Uladzimir'', russian: Владимир, ''Vladimir'', uk, Володимир, ''Volodymyr''. Se ...

gave kvass among other beverages to the people, while celebrating the Christianization of Kievan Rus'

Christianization ( or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of an individual, a practice, a place or a whole society. It began in the Roman Empire, conti ...

. Kvass is also known as a main ingredient in okroshka

Okróshka (russian: окро́шка) is a cold soup of Russian origin and probably originated in the Volga region.

The classic soup is a mix of mostly raw vegetables (like cucumbers, radishes and spring onions), boiled potatoes, eggs, cooked ...

, a Russian cold soup. ; Multidomed church

: The multidomed church is a typical form of Russian church architecture, which distinguishes Russia from other Eastern Orthodox nations and Christian denominations. Indeed, the earliest Russian churches built just after the

; Multidomed church

: The multidomed church is a typical form of Russian church architecture, which distinguishes Russia from other Eastern Orthodox nations and Christian denominations. Indeed, the earliest Russian churches built just after the Christianization of Kievan Rus'

Christianization ( or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of an individual, a practice, a place or a whole society. It began in the Roman Empire, conti ...

, were multi-domed, which led some historians to speculate what Russian pre-Christian pagan temples might have looked like. Namely, these early churches were 13-domed wooden Saint Sophia Cathedral in Novgorod

The Cathedral of Holy Wisdom (the Holy Wisdom of God) in Veliky Novgorod is the cathedral church of the Metropolitan of Novgorod and the mother church of the Novgorodian Eparchy.

History

The 38-metre-high, five-domed, stone cathedral was built ...

(989) and 25-domed stone Desyatinnaya Church

The Church of the Tithes or Church of the Dormition of the Virgin ( uk, Десятинна Церква, ) was the first stone church in Kyiv.Mariya Lesiv, ''The Return of Ancestral Gods: Modern Ukrainian Paganism as an Alternative Vision for ...

in Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

(989–996). The number of domes typically has a symbolical meaning in Russian architecture

The architecture of Russia refers to the architecture of modern Russia as well as the architecture of both the original Kievan Rus’ state, the Russian principalities, and Imperial Russia. Due to the geographical size of modern and imperial ...

, for example 13 domes symbolize Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and relig ...

with 12 Apostles

An apostle (), in its literal sense, is an emissary, from Ancient Greek ἀπόστολος (''apóstolos''), literally "one who is sent off", from the verb ἀποστέλλειν (''apostéllein''), "to send off". The purpose of such sending ...

, while 25 domes mean the same with additional 12 Prophets from the Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

. Multiple domes of Russian churches were often made of wood and were comparatively smaller than the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

domes. ; Kissel

: ''Kissel'' or ''kisel'' is a dessert that consists of sweetened juice, typically that of berries, thickened with

; Kissel

: ''Kissel'' or ''kisel'' is a dessert that consists of sweetened juice, typically that of berries, thickened with oat

The oat (''Avena sativa''), sometimes called the common oat, is a species of cereal grain grown for its seed, which is known by the same name (usually in the plural, unlike other cereals and pseudocereals). While oats are suitable for human con ...

s, cornstarch

Corn starch, maize starch, or cornflour (British English) is the starch derived from corn (maize) grain. The starch is obtained from the endosperm of the kernel. Corn starch is a common food ingredient, often used to thicken sauces or sou ...

or potato starch

Potato starch is starch extracted from potatoes. The cells of the root tubers of the potato plant contain leucoplasts (starch grains). To extract the starch, the potatoes are crushed, and the starch grains are released from the destroyed cells. ...

, with red wine

Red wine is a type of wine made from dark-colored grape varieties. The color of the wine can range from intense violet, typical of young wines, through to brick red for mature wines and brown for older red wines. The juice from most purple gr ...

or dried fruit

Dried fruit is fruit from which the majority of the original water content has been removed either naturally, through sun drying, or through the use of specialized dryers or dehydrators. Dried fruit has a long tradition of use dating back to th ...

s added sometimes. The dessert can be served either hot or cold, and if made using less thickening starch it can be consumed as a beverage, which is common in Russia. Kissel was mentioned for the first time in the Primary Chronicle

The ''Tale of Bygone Years'' ( orv, Повѣсть времѧньныхъ лѣтъ, translit=Pověstĭ vremęnĭnyxŭ lětŭ; ; ; ; ), often known in English as the ''Rus' Primary Chronicle'', the ''Russian Primary Chronicle'', or simply the ...

, where it forms part of the story of how a besieged Russian city was saved from nomadic Pechenegs

The Pechenegs () or Patzinaks tr, Peçenek(ler), Middle Turkic: , ro, Pecenegi, russian: Печенег(и), uk, Печеніг(и), hu, Besenyő(k), gr, Πατζινάκοι, Πετσενέγοι, Πατζινακίται, ka, პა� ...

.

11th century

; Birch bark document

: A birch bark document is a document written on pieces of

; Birch bark document

: A birch bark document is a document written on pieces of birch bark

Birch bark or birchbark is the bark of several Eurasian and North American birch trees of the genus ''Betula''.

The strong and water-resistant cardboard-like bark can be easily cut, bent, and sewn, which has made it a valuable building, craftin ...

. This form of writing material was developed independently by several ancient cultures. In Rus' the usage of the specially prepared birch bark as a cheap replacement for pergament or paper

Paper is a thin sheet material produced by mechanically or chemically processing cellulose fibres derived from wood, rags, grasses or other vegetable sources in water, draining the water through fine mesh leaving the fibre evenly distribu ...

became widespread soon after the Christianization

Christianization ( or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of an individual, a practice, a place or a whole society. It began in the Roman Empire, conti ...

of the country. The earliest Russian birch bark documents (likely written in the first quarter of the 11th century) have been found in Veliky Novgorod

Veliky Novgorod ( rus, links=no, Великий Новгород, t=Great Newtown, p=vʲɪˈlʲikʲɪj ˈnovɡərət), also known as just Novgorod (), is the largest city and administrative centre of Novgorod Oblast, Russia. It is one of the ...

. In total, more than 1000 such documents have been discovered, most of them in Novgorod and the rest in other ancient cities in Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

, Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

and Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

. Many birch bark documents were written by common people rather than by clergy or nobility. This fact led some historians to suggest that before the Mongol invasion of Rus'

The Mongol Empire invaded and conquered Kievan Rus' in the 13th century, destroying numerous southern cities, including the largest cities, Kiev (50,000 inhabitants) and Chernihiv (30,000 inhabitants), with the only major cities escaping de ...

the level of literacy

Literacy in its broadest sense describes "particular ways of thinking about and doing reading and writing" with the purpose of understanding or expressing thoughts or ideas in Writing, written form in some specific context of use. In other wo ...

in the country might have been considerably higher than in contemporary Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

.Koch

Koch may refer to:

People

* Koch (surname), people with this surname

* Koch dynasty, a dynasty in Assam and Bengal, north east India

* Koch family

* Koch people (or Koche), an ethnic group originally from the ancient Koch kingdom in north east I ...

/ Icebreaker

An icebreaker is a special-purpose ship or boat designed to move and navigate through ice-covered waters, and provide safe waterways for other boats and ships. Although the term usually refers to ice-breaking ships, it may also refer to smaller ...

: The ''koch'' was an ancient form of icebreaker

An icebreaker is a special-purpose ship or boat designed to move and navigate through ice-covered waters, and provide safe waterways for other boats and ships. Although the term usually refers to ice-breaking ships, it may also refer to smaller ...

, being a special type of one or two small wooden sailing ship

A sailing ship is a sea-going vessel that uses sails mounted on masts to harness the power of wind and propel the vessel. There is a variety of sail plans that propel sailing ships, employing square-rigged or fore-and-aft sails. Some ships ...

s with a mast, used for voyages in the icy conditions of the Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

seas and Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

n rivers. The koch was developed by the Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

n Pomors

Pomors or Pomory ( rus, помо́ры, p=pɐˈmorɨ, ''seasiders'') are an ethnographic group descended from Russian settlers, primarily from Veliky Novgorod, living on the White Sea coasts and the territory whose southern border lies on a ...

in the 11th century, when they started settling on the White Sea

The White Sea (russian: Белое море, ''Béloye móre''; Karelian and fi, Vienanmeri, lit. Dvina Sea; yrk, Сэрако ямʼ, ''Serako yam'') is a southern inlet of the Barents Sea located on the northwest coast of Russia. It is s ...

shores. The koch's hull was protected by a belt of ice-floe resistant flush skin-planking (made of oak or larch

Larches are deciduous conifers in the genus ''Larix'', of the family Pinaceae (subfamily Laricoideae). Growing from tall, they are native to much of the cooler temperate northern hemisphere, on lowlands in the north and high on mountains fur ...

) along the variable water-line, and had a false keel for on-ice portage

Portage or portaging (Canada: ; ) is the practice of carrying water craft or cargo over land, either around an obstacle in a river, or between two bodies of water. A path where items are regularly carried between bodies of water is also called a ...

. If a koch was in danger of being trapped in the ice-fields, its rounded bodylines below the surface would allow for the ship to be pushed up out of the water and onto the ice with no damage. In the 19th century similar protective features were adopted to modern icebreaker

An icebreaker is a special-purpose ship or boat designed to move and navigate through ice-covered waters, and provide safe waterways for other boats and ships. Although the term usually refers to ice-breaking ships, it may also refer to smaller ...

s. ; Gudok

: The gudok is an ancient East Slavic string

; Gudok

: The gudok is an ancient East Slavic string musical instrument

A musical instrument is a device created or adapted to make musical sounds. In principle, any object that produces sound can be considered a musical instrument—it is through purpose that the object becomes a musical instrument. A person who pl ...

, played with a bow. It usually had three strings, two of them tuned in unison

In music, unison is two or more musical parts that sound either the same pitch or pitches separated by intervals of one or more octaves, usually at the same time. ''Rhythmic unison'' is another term for homorhythm.

Definition

Unison or per ...

and played as a drone, the third tuned a fifth higher. All three strings were in the same plane at the bridge, so that a bow could make them all sound at the same time. Sometimes the gudok also had several sympathetic strings

Sympathetic strings or resonance strings are auxiliary strings found on many Indian musical instruments, as well as some Western Baroque instruments and a variety of folk instruments. They are typically not played directly by the performer (excep ...

(up to eight) under the sounding board

A sounding board, also known as a tester and abat-voix is a structure placed above and sometimes also behind a pulpit or other speaking platform that helps to project the sound of the speaker. It is usually made of wood. The structure may be spe ...

. These made the gudok's sound warm and rich. It was also possible to play while standing or dancing, which made it popular among skomorokhs. The name ''gudok'' comes from the 17th century, however the same type of instrument existed from 11th to 16th century, but was called ''smyk''.

;Medovukha

Medovukha ( rus, медову́ха, medovúxa, mʲɪdɐˈvuxə; uk, меду́ха, medúxa, ; be, мяду́ха, медаву́ха, miadúxa, miedavúxa, , ) is a Slavic honey-based alcoholic beverage very similar to mead, but it is ma ...

: ''Medovukha'' is an old Slavic honey

Honey is a sweet and viscous substance made by several bees, the best-known of which are honey bees. Honey is made and stored to nourish bee colonies. Bees produce honey by gathering and then refining the sugary secretions of plants (primar ...

-based alcoholic beverage very similar to mead

Mead () is an alcoholic beverage made by fermenting honey mixed with water, and sometimes with added ingredients such as fruits, spices, grains, or hops. The alcoholic content ranges from about 3.5% ABV to more than 20%. The defining characte ...

, but much cheaper and faster to make. Since the old times the Slavs exported the fermented

Fermentation is a metabolic process that produces chemical changes in organic substrates through the action of enzymes. In biochemistry, it is narrowly defined as the extraction of energy from carbohydrates in the absence of oxygen. In food p ...

mead as a luxury product to Europe in huge quantities. Fermentation occurs naturally over 15 to 50 years, originally rendering the product very expensive and only accessible to the nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The character ...

. However, in the 11th century East Slavs found that fermentation occurred much faster when the honey mixture was heated, enabling medovukha to become a commonly available drink in the territory of Rus'. In the 14th century, the invention of distillation

Distillation, or classical distillation, is the process of separating the components or substances from a liquid mixture by using selective boiling and condensation, usually inside an apparatus known as a still. Dry distillation is the he ...

made it possible to create a prototype of the modern medovukha, however vodka

Vodka ( pl, wódka , russian: водка , sv, vodka ) is a clear distilled alcoholic beverage. Different varieties originated in Poland, Russia, and Sweden. Vodka is composed mainly of water and ethanol but sometimes with traces of impuriti ...

was invented at the same time and gradually surpassed medovukha in popularity.

;1048

;1048 Russian fist fighting

Russian boxing (russian: Кулачный бой, Kulachniy Boy, fist fighting, pugilism) is the traditional bare-knuckle boxing of Rus' and then Russia. Boxers will often train by punching buckets of sand to strengthen bones, and prepare minutes ...

: Russian fist fighting is an ancient Russian combat sport

A combat sport, or fighting sport, is a competitive contact sport that usually involves one-on-one combat. In many combat sports, a contestant wins by scoring more points than the opponent, submitting the opponent with a hold, disabling the oppo ...

, similar to modern boxing

Boxing (also known as "Western boxing" or "pugilism") is a combat sport in which two people, usually wearing protective gloves and other protective equipment such as hand wraps and mouthguards, throw punches at each other for a predetermined ...

. However, it features some indigenous techniques and often fought in collective events called ''Stenka na Stenku'' ("Wall against Wall"). It has existed since the times of Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas o ...

, first mentioned in the Primary Chronicle

The ''Tale of Bygone Years'' ( orv, Повѣсть времѧньныхъ лѣтъ, translit=Pověstĭ vremęnĭnyxŭ lětŭ; ; ; ; ), often known in English as the ''Rus' Primary Chronicle'', the ''Russian Primary Chronicle'', or simply the ...

in the year 1048. The government and the Russian Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = ru

, image = Moscow July 2011-7a.jpg

, imagewidth =

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia

, abbreviation = ROC

, type ...

often tried to prohibit the fights; however, fist fighting remained popular until the 19th century, while in the 20th century some of the old techniques were adopted for the modern Russian martial arts

There are a number of martial arts styles and schools of Russian origin. Traditional Russian fist fighting has existed since the 1st millennium AD. It was outlawed in the Russian Empire in 1832. However, it has seen a resurgence after the break- ...

.

12th century

; Pernach

: The ''pernach'' is a type of flanged mace developed since the 12th century in the region of

; Pernach

: The ''pernach'' is a type of flanged mace developed since the 12th century in the region of Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas o ...

and later widely used throughout Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

. The name comes from the Russian word ''перо'' (''pero'') meaning feather

Feathers are epidermal growths that form a distinctive outer covering, or plumage, on both avian (bird) and some non-avian dinosaurs and other archosaurs. They are the most complex integumentary structures found in vertebrates and a premie ...

, reflecting the form of pernach that resembled an arrow

An arrow is a fin-stabilized projectile launched by a bow. A typical arrow usually consists of a long, stiff, straight shaft with a weighty (and usually sharp and pointed) arrowhead attached to the front end, multiple fin-like stabilizers ...

with fletching

Fletching is the fin-shaped aerodynamic stabilization device attached on arrows, bolts, darts, or javelins, and are typically made from light semi-flexible materials such as feathers or bark. Each piece of such fin is a fletch, also known as a ...

. The most popular variety of pernach had six flange

A flange is a protruded ridge, lip or rim (wheel), rim, either external or internal, that serves to increase shear strength, strength (as the flange of an iron beam (structure), beam such as an I-beam or a T-beam); for easy attachment/transfer of ...

s and was called ''shestopyor'' (from Russian ''shest'' and ''pero'', that is ''six-feathered''). Pernach was the first form of the flanged mace to find wide usage. It was perfectly suited to defeat plate armour

Plate armour is a historical type of personal body armour made from bronze, iron, or steel plates, culminating in the iconic suit of armour entirely encasing the wearer. Full plate steel armour developed in Europe during the Late Middle Ages, ...

and plate mail. In later times it was often used as a symbol of power by military leaders in Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

.

;Shashka

The shashka ( ady, сэшхуэ, – ''long-knife'') (russian: шашка) or shasqua, is a kind of sabre; a single-edged, single-handed, and guardless backsword. In appearance, the ''shashka'' is midway between a typically curved sabre and a ...

: The shashka is a special kind of sabre

A sabre (French: �sabʁ or saber in American English) is a type of backsword with a curved blade associated with the light cavalry of the early modern and Napoleonic periods. Originally associated with Central European cavalry such as t ...

, a very sharp, single-edged, single-handed, and guardless sword

A sword is an edged, bladed weapon intended for manual cutting or thrusting. Its blade, longer than a knife or dagger, is attached to a hilt and can be straight or curved. A thrusting sword tends to have a straighter blade with a pointed ti ...

. In appearance, the shashka is midway between a full sabre and a straight sword. It has a slightly curved blade, and could be effective for both slashing and thrusting. Originally the shashka was developed in the 12th century by Circassians

The Circassians (also referred to as Cherkess or Adyghe; Adyghe and Kabardian: Адыгэхэр, romanized: ''Adıgəxər'') are an indigenous Northwest Caucasian ethnic group and nation native to the historical country-region of Circassia ...

in the Northern Caucasus

The North Caucasus, ( ady, Темыр Къафкъас, Temır Qafqas; kbd, Ишхъэрэ Къаукъаз, İṩxhərə Qauqaz; ce, Къилбаседа Кавказ, Q̇ilbaseda Kavkaz; , os, Цӕгат Кавказ, Cægat Kavkaz, inh, ...

. These lands were integrated into the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

in the 18th century. By that time shashka was adopted as their main cold weapon by Russian Cossacks

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

. ;

;Treshchotka

A treshchotka ( rus, трещо́тка, p=trʲɪˈɕːɵtkə, singular; sometimes referred to in the plural, treshchotki, rus, трещо́тки, p=trʲɪˈɕːɵtkʲɪ) is a Russian folk music idiophone percussion instrument which is used to i ...

: The ''treshchotka'', sometimes referred in plural as ''treshchotki'', is a Russian folk music

Russian folk music specifically deals with the folk music traditions of the ethnic Russian people.

Ethnic styles in the modern era

The performance and promulgation of ethnic music in Russia has a long tradition. Initially it was intertwined with ...

idiophone

An idiophone is any musical instrument that creates sound primarily by the vibration of the instrument itself, without the use of air flow (as with aerophones), strings ( chordophones), membranes ( membranophones) or electricity ( electroph ...

instrument which is used to imitate hand clapping. Basically it is a set of small boards on a string that get clapped together as a group. There are no known documents confirming the usage of the treshchotka in ancient Russia, however, the remnants of what might have been the earliest 12th-century treshchotka were recently found in Novgorod

Veliky Novgorod ( rus, links=no, Великий Новгород, t=Great Newtown, p=vʲɪˈlʲikʲɪj ˈnovɡərət), also known as just Novgorod (), is the largest city and administrative centre of Novgorod Oblast, Russia. It is one of the ...

.

;1149 bear spear

: The bear spear or ''rogatina'' was a medieval type of spear

A spear is a pole weapon consisting of a shaft, usually of wood, with a pointed head. The head may be simply the sharpened end of the shaft itself, as is the case with fire hardened spears, or it may be made of a more durable material fastene ...

used in bear hunting

Bear hunting is the act of hunting bears. Bears have been hunted since prehistoric times for their meat and fur. In addition to being a source of food, in modern times they have been favoured by big game hunters due to their size and ferocity. B ...

and also to hunt other large animals, like wisent

The European bison (''Bison bonasus'') or the European wood bison, also known as the wisent ( or ), the zubr (), or sometimes colloquially as the European buffalo, is a European species of bison. It is one of two extant species of bison, along ...

s and war horses. The sharpened head of a bear spear was enlarged and usually had the form of a bay leaf

The bay leaf is an aromatic leaf commonly used in cooking. It can be used whole, either dried or fresh, in which case it is removed from the dish before consumption, or less commonly used in ground form. It may come from several species of tr ...

. Right under the head there was a short crosspiece that helped to fix the spear in the body of an animal. Often it was placed against the ground on its rear point, which made it easier to absorb the impact of the attacking beast. The Russian chronicles first mention rogatina as a military weapon in the year 1149, and as a hunting weapon in the year 1255.

13th century

; Sokha : The sokha is a light woodenplough

A plough or plow ( US; both ) is a farm tool for loosening or turning the soil before sowing seed or planting. Ploughs were traditionally drawn by oxen and horses, but in modern farms are drawn by tractors. A plough may have a wooden, iron or ...

which could be pulled by one horse. Its origin was in northern Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

, most likely in the Novgorod Republic

The Novgorod Republic was a medieval state that existed from the 12th to 15th centuries, stretching from the Gulf of Finland in the west to the northern Ural Mountains in the east, including the city of Novgorod and the Lake Ladoga regions of mod ...

, where it was used as early as in the 13th century. A characteristic feature of sokha construction is the bifurcated plowing tip (рассоха), so that a sokha has two plowshares, later made of metal, which cut the soil. The sokha is an evolution of a scratch-plough

The ard, ard plough, or scratch plough is a simple light plough without a mouldboard. It is symmetrical on either side of its line of draft and is fitted with a symmetrical share that traces a shallow furrow but does not invert the soil. It be ...

by an addition of a spade

A spade is a tool primarily for digging consisting of a long handle and blade, typically with the blade narrower and flatter than the common shovel. Early spades were made of riven wood or of animal bones (often shoulder blades). After the a ...

-like detail which turns the cut soil over (in regular ploughs the curved mouldboard both cuts and turns the soil). ;

;Pelmeni

Pelmeni (russian: пельмени—plural, ; pelmen, russian: пельмень, link=no—singular, ) are dumplings of Russian cuisine that consist of a filling wrapped in thin, unleavened dough.

It is debated whether they originated in Ura ...

: ''Pelmeni'' is a dish originating from Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

, now considered part of Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

n national cuisine. It is a type of dumpling

Dumpling is a broad class of dishes that consist of pieces of dough (made from a variety of starch sources), oftentimes wrapped around a filling. The dough can be based on bread, flour, buckwheat or potatoes, and may be filled with meat, ...

consisting of a filling that is wrapped in thin unleavened dough

Dough is a thick, malleable, sometimes elastic paste made from grains or from leguminous or chestnut crops. Dough is typically made by mixing flour with a small amount of water or other liquid and sometimes includes yeast or other leavenin ...

. The word ''pelmeni'' comes from the Finno-Ugric Komi, Udmurt, and Mansi

Mansi may refer to:

People

* Mansi people, an indigenous people living in Tyumen Oblast, Russia

** Mansi language

* Giovanni Domenico Mansi

Gian (Giovanni) Domenico Mansi (16 February 1692 – 27 September 1769) was an Italian prelate, theolog ...

languages. It is unclear when pelmeni entered the cuisines of indigenous Siberian people and when it first appeared in Russian cuisine

Russian cuisine is a collection of the different dishes and cooking traditions of the Russian people as well as a list of culinary products popular in Russia, with most names being known since pre-Soviet times, coming from all kinds of social ...

, but most likely it was during the Mongol conquests

The Mongol invasions and conquests took place during the 13th and 14th centuries, creating history's largest contiguous empire: the Mongol Empire ( 1206-1368), which by 1300 covered large parts of Eurasia. Historians regard the Mongol devastatio ...

and Mongol-Tatar invasion of Rus' in the 13th century, when Mongol-Tatars

The Mongol Empire of the 13th and 14th centuries was the largest contiguous land empire in history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Europe, ...

took the basic idea from the Chinese dumpling

Dumpling is a broad class of dishes that consist of pieces of dough (made from a variety of starch sources), oftentimes wrapped around a filling. The dough can be based on bread, flour, buckwheat or potatoes, and may be filled with meat, ...

s and brought it to Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

and Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

.dome

A dome () is an architectural element similar to the hollow upper half of a sphere. There is significant overlap with the term cupola, which may also refer to a dome or a structure on top of a dome. The precise definition of a dome has been a m ...

whose shape resembles an onion

An onion (''Allium cepa'' L., from Latin ''cepa'' meaning "onion"), also known as the bulb onion or common onion, is a vegetable that is the most widely cultivated species of the genus '' Allium''. The shallot is a botanical variety of the on ...

. Such domes are often larger in diameter than the drum

The drum is a member of the percussion group of musical instruments. In the Hornbostel-Sachs classification system, it is a membranophone. Drums consist of at least one membrane, called a drumhead or drum skin, that is stretched over a ...

upon which they are set, and their height usually exceeds their width. The whole bulbous structure tapers smoothly to a point. The so-called onion dome is the dominant form for church domes in Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

, and though the earliest preserved Russian domes of the type date from the 16th century, illustrations of the old chronicles indicate that they were used since the late 13th century.

Grand Duchy of Moscow

14th century

Lapta * Lapta is a Russianball game

This is a list of ball games and ball sports that include a ball as a key element in the activity, usually for scoring points.

Ball games

Ball sports fall within many sport categories, some sports within multiple categories, including:

*Bat-and- ...

played with a bat, similar to modern baseball

Baseball is a bat-and-ball sport played between two teams of nine players each, taking turns batting and fielding. The game occurs over the course of several plays, with each play generally beginning when a player on the fielding t ...

. The game is played outside on a field the size of 20 x 25 sazhen

A native system of weights and measures was used in Imperial Russia and after the Russian Revolution, but it was abandoned after 21 July 1925, when the Soviet Union adopted the metric system, per the order of the Council of People's Commissars ...

s (about 140 x 175 feet). Points are earned by hitting the ball, served by a player of the opposite team, and sending it as far as possible, then running across the field to the ''kon'' line, and if possible running back to the ''gorod'' line. The running player should try to avoid being hit with the ball, which is thrown by opposing team members. The most ancient balls and bats for lapta were found in 14th-century layers during excavations in Novgorod

Veliky Novgorod ( rus, links=no, Великий Новгород, t=Great Newtown, p=vʲɪˈlʲikʲɪj ˈnovɡərət), also known as just Novgorod (), is the largest city and administrative centre of Novgorod Oblast, Russia. It is one of the ...

.

Zvonnitsa

A zvonnitsa (russian: звонница; uk, дзвіниця, dzvinytsia; pl, dzwonnica parawanowa; ro, zvoniţă) is a large rectangular structure containing multiple arches or beams that support bells, and a basal platform where bell ringers ...

* A zvonnitsa is a large rectangular structure containing multiple arch

An arch is a vertical curved structure that spans an elevated space and may or may not support the weight above it, or in case of a horizontal arch like an arch dam, the hydrostatic pressure against it.

Arches may be synonymous with vau ...

es or beams that carry bell

A bell is a directly struck idiophone percussion instrument. Most bells have the shape of a hollow cup that when struck vibrates in a single strong strike tone, with its sides forming an efficient resonator. The strike may be made by an inte ...

s, where bell ringer

A bell-ringer is a person who rings a bell, usually a church bell, by means of a rope or other mechanism.

Despite some automation of bells for random swinging, there are still many active bell-ringers in the world, particularly those with an adv ...

s stand on its basement level and perform the ringing using long ropes, like playing on a kind of giant musical instrument

A musical instrument is a device created or adapted to make musical sounds. In principle, any object that produces sound can be considered a musical instrument—it is through purpose that the object becomes a musical instrument. A person who pl ...

. It was an alternative to bell tower

A bell tower is a tower that contains one or more bells, or that is designed to hold bells even if it has none. Such a tower commonly serves as part of a Christian church, and will contain church bells, but there are also many secular bell tow ...

in the medieval architecture of Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

and some Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

an countries. Zvonnitsa appeared in Russia in the 14th century and was widely used until the 17th century. Sometimes it was mounted right atop the church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a building for Christian religious activities

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian communal worship

* Chri ...

building, resulting in the special type of church called ''pod zvonom'' ("under ringing") or ''izhe pod kolokoly'' ("under bells"). The most famous example of this type of a church is the Church of St. Ivan of the Ladder adjacent to the Ivan the Great Bell Tower

The Ivan the Great Bell Tower (russian: Колокольня Иван Великий, ''Kolokol'nya Ivan Velikiy'') is a church tower inside the Moscow Kremlin complex. With a total height of , it is the tallest tower and structure of the Kreml ...

in the Moscow Kremlin

The Kremlin ( rus, Московский Кремль, r=Moskovskiy Kreml', p=ˈmɐˈskofskʲɪj krʲemlʲ, t=Moscow Kremlin) is a fortified complex in the center of Moscow founded by the Rurik dynasty. It is the best known of the kremlins (R ...

.

Anbur script The alphabet was introduced by a Russian missionary, Stepan Khrap, also known as Saint Stephen of Perm (Степан Храп, св. Стефан Пермский) in 1372. The name Abur is derived from the names of the first two characters: An and Bur. The alphabet derived from Cyrillic and Greek, and Komi tribal signs, the latter being similar in the appearance to runes or siglas poveiras, because they were created by incisions, rather than by usual writing. The alphabet was in use until the 17th century, when it was superseded by the Cyrillic script. Abur was also used as cryptographic writing for the Russian language.

1376 Sarafan

A sarafan ( rus, сарафа́н, p=sərɐˈfan, from fa, سراپا ''sarāpā'', literally " romhead to feet") is a long, trapezoidal Russian jumper dress (pinafore dress) worn by girls and women and forming part of Russian traditional fo ...

* The sarafan is a long, shapeless pinafore

A pinafore (colloquially a pinny in British English) is a sleeveless garment worn as an apron.

Pinafores may be worn as a decorative garment and as a protective apron. A related term is ''pinafore dress'' (known as a ''jumper'' in Ameri ...

-type jumper dress, a part of the traditional Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

n folk costume worn by women and girls. Sarafans could be of single piece construction with thin shoulder straps over which a corset

A corset is a support garment commonly worn to hold and train the torso into a desired shape, traditionally a smaller waist or larger bottom, for aesthetic or medical purposes (either for the duration of wearing it or with a more lasting eff ...

is sometimes worn, giving the shape of the body of a smaller triangle

A triangle is a polygon with three edges and three vertices. It is one of the basic shapes in geometry. A triangle with vertices ''A'', ''B'', and ''C'' is denoted \triangle ABC.

In Euclidean geometry, any three points, when non- colline ...

over a larger one. It comes in different styles such as the simpler black, flower- or check-patterned versions formerly used for everyday wear, or elaborate brocade versions formerly reserved for special occasions. Chronicles first mention it in the year 1376, and since that time it was worn well until the 20th century. It is now worn as a folk costume for performing Russian folk songs and folk dancing. Plain sarafans are still designed and worn today as a summer-time light dress.

15th century

* Kholui miniatureBardiche

A bardiche , berdiche, bardische, bardeche, or berdish is a type of polearm used from the 14th to 17th centuries in Europe. Ultimately a descendant of the medieval sparth or Danish axe, the bardiche proper appears around 1400, but there are nu ...

* The bardiche was a long poleaxe, that is a type of weapon combining the features of an axe

An axe ( sometimes ax in American English; see spelling differences) is an implement that has been used for millennia to shape, split and cut wood, to harvest timber, as a weapon, and as a ceremonial or heraldic symbol. The axe has ma ...

and a polearm

A polearm or pole weapon is a close combat weapon in which the main fighting part of the weapon is fitted to the end of a long shaft, typically of wood, thereby extending the user's effective range and striking power. Polearms are predominantl ...

, known primarily in Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

where it was used instead of halberd

A halberd (also called halbard, halbert or Swiss voulge) is a two-handed pole weapon that came to prominent use during the 13th, 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. The word ''halberd'' is cognate with the German word ''Hellebarde'', deriving from ...

s. Occasionally such weapons were made in Antiquity

Antiquity or Antiquities may refer to:

Historical objects or periods Artifacts

*Antiquities, objects or artifacts surviving from ancient cultures

Eras

Any period before the European Middle Ages (5th to 15th centuries) but still within the histo ...

and Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

, but the regular and widespread usage of bardiches started in early-15th-century Russia. It was probably developed from the Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and S ...

n broad axe

A broadaxe is a large (broad)-headed axe. There are two categories of cutting edge on broadaxes, both are used for shaping logs by hewing. On one type, one side is flat, and the other side beveled, a basilled edge, also called a side axe, single ...

, but in Scandinavia it appeared only in the late 15th century. In the 16th century the bardiche became a weapon associated with the streltsy

, image = 01 106 Book illustrations of Historical description of the clothes and weapons of Russian troops.jpg

, image_size =

, alt =

, caption =

, dates = 1550–1720

, disbanded =

, country = Tsardom of Russia

, allegiance = Streltsy ...

, Russian guardsmen armed with firearms

A firearm is any type of gun designed to be readily carried and used by an individual. The term is legally defined further in different countries (see Legal definitions).

The first firearms originated in 10th-century China, when bamboo tubes ...

, who used bardiches to rest handguns upon when firing.

Boyar hat

The boyar hat (russian: боярская шапка, more correct Russian name is горлатная шапка, gorlatnaya hat) was a fur hat worn by Russian nobility between the 15th and 17th centuries, most notably by boyars, for whom it was a ...

* The boyar hat, also known as gorlatnaya hat, was a fur hat worn by Russian nobility between the 15th and 17th centuries, most notably by boyar

A boyar or bolyar was a member of the highest rank of the feudal nobility in many Eastern European states, including Kievan Rus', Bulgaria, Russia, Wallachia and Moldavia, and later Romania, Lithuania and among Baltic Germans. Boyars were ...

s, for whom it was a sign of their social status. The higher hat indicated higher status. In average, it was one ell in height, having the form of a cylinder

A cylinder (from ) has traditionally been a three-dimensional solid, one of the most basic of curvilinear geometric shapes. In elementary geometry, it is considered a prism with a circle as its base.

A cylinder may also be defined as an ...

with more broad upper part, velvet

Weave details visible on a purple-colored velvet fabric

Velvet is a type of woven tufted fabric in which the cut threads are evenly distributed, with a short pile, giving it a distinctive soft feel. By extension, the word ''velvety'' means ...

or brocade

Brocade is a class of richly decorative shuttle-woven fabrics, often made in colored silks and sometimes with gold and silver threads. The name, related to the same root as the word " broccoli", comes from Italian ''broccato'' meaning "emb ...

on top and a main body made of fox, marten

A marten is a weasel-like mammal in the genus ''Martes'' within the subfamily Guloninae, in the family Mustelidae. They have bushy tails and large paws with partially retractile claws. The fur varies from yellowish to dark brown, depending on ...

or sable

The sable (''Martes zibellina'') is a species of marten, a small omnivorous mammal primarily inhabiting the forest environments of Russia, from the Ural Mountains throughout Siberia, and northern Mongolia. Its habitat also borders eastern Kaza ...

fur. Today the hat is sometimes used in the Russian fashion

Fashion is a form of self-expression and autonomy at a particular period and place and in a specific context, of clothing, footwear, lifestyle, accessories, makeup, hairstyle, and body posture. The term implies a look defined by the fash ...

.

Gulyay-gorod

Gulyay-gorod, also guliai-gorod (russian: Гуля́й-го́род, literally: "wandering town"), was a mobile fortification used by the Russian army between the 16th and the 17th centuries.

History and Terminology

The use of term ''gulyay-go ...

* The gulyay-gorod (literally "wandering town") was a mobile fortification made from large wall-sized prefabricated shields set on wagon

A wagon or waggon is a heavy four-wheeled vehicle pulled by draught animals or on occasion by humans, used for transporting goods, commodities, agricultural materials, supplies and sometimes people.

Wagons are immediately distinguished from ...

s or sled

A sled, skid, sledge, or sleigh is a land vehicle that slides across a surface, usually of ice or snow. It is built with either a smooth underside or a separate body supported by two or more smooth, relatively narrow, longitudinal runners ...

s, a development of the wagon fort concept. The usage of installable shields instead of permanently armoured wagons was cheaper and allowed more possible configurations to be assembled. Such mobile structures were used mostly in the open steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without trees apart from those near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the temperate gras ...

, where few natural shelters could be found. The wide-scale usage of gulyay-gorod started during the Russo-Kazan Wars

The Russo-Kazan Wars was a series of wars fought between the Grand Duchy of Moscow and the Khanate of Kazan from 1439, until Kazan was finally conquered by the Tsardom of Russia under Ivan the Terrible in 1552.

General

Before it separated fr ...

, and later it was often used by the Ukrainian Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Cossacks, Zaporozhian Cossack Army, Zaporozhian Host, (, or uk, Військо Запорізьке, translit=Viisko Zaporizke, translit-std=ungegn, label=none) or simply Zaporozhians ( uk, Запорожці, translit=Zaporoz ...

.

Ukha

Ukha ( rus, уха) is a clear Russian soup, made from various types of fish such as bream, wels catfish, northern pike, or even ruffe. It usually contains root vegetables, parsley root, leek, potato, bay leaf, dill, tarragon, and green par ...

* Ukha is a Russian soup, made with broth

Broth, also known as bouillon (), is a savory liquid made of water in which meat, fish or vegetables have been simmered for a short period of time. It can be eaten alone, but it is most commonly used to prepare other dishes, such as soups, ...

and fish like salmon

Salmon () is the common name for several commercially important species of euryhaline ray-finned fish from the family Salmonidae, which are native to tributaries of the North Atlantic (genus '' Salmo'') and North Pacific (genus '' Onco ...

or cod, root vegetables, parsley root, leek

The leek is a vegetable, a cultivar of '' Allium ampeloprasum'', the broadleaf wild leek ( syn. ''Allium porrum''). The edible part of the plant is a bundle of leaf sheaths that is sometimes erroneously called a stem or stalk. The genus '' Al ...

, potato

The potato is a starchy food, a tuber of the plant ''Solanum tuberosum'' and is a root vegetable native to the Americas. The plant is a perennial in the nightshade family Solanaceae.

Wild potato species can be found from the southern Uni ...

, bay leaf, lime, dill

Dill (''Anethum graveolens'') is an annual herb in the celery family Apiaceae. It is the only species in the genus ''Anethum''. Dill is grown widely in Eurasia, where its leaves and seeds are used as a herb or spice for flavouring food.

Growth ...

, green parsley

Parsley, or garden parsley (''Petroselinum crispum'') is a species of flowering plant in the family Apiaceae that is native to the central and eastern Mediterranean region (Sardinia, Lebanon, Israel, Cyprus, Turkey, southern Italy, Greece, ...

and spiced with black pepper, cinnamon and cloves. Fish like perch

Perch is a common name for fish of the genus ''Perca'', freshwater gamefish belonging to the family Percidae. The perch, of which three species occur in different geographical areas, lend their name to a large order of vertebrates: the Per ...

, tench

The tench or doctor fish (''Tinca tinca'') is a fresh- and brackish-water fish of the order Cypriniformes found throughout Eurasia from Western Europe including the British Isles east into Asia as far as the Ob and Yenisei Rivers. It is ...

es, sheatfish and burbot

The burbot (''Lota lota'') is the only gadiform (cod-like) freshwater fish. It is also known as bubbot, mariah, loche, cusk, freshwater cod, freshwater ling, freshwater cusk, the lawyer, coney-fish, lingcod, and eelpout. The species is closely ...

were used to add flavour to the soup. ''Ukha'' as a name in the Russian cuisine

Russian cuisine is a collection of the different dishes and cooking traditions of the Russian people as well as a list of culinary products popular in Russia, with most names being known since pre-Soviet times, coming from all kinds of social ...

for fish broth was established only in the late 17th to early 18th centuries. In earlier times this name was first given to thick meat broths, and then later chicken. Beginning from the 15th century, fish was used more and more often to prepare ukha, thus creating a dish that had a distinctive taste among soups.

Russian oven

The Russian stove (russian: русская печь) is a type of masonry stove that first appeared in the 15th century. It is used both for cooking and domestic heating in traditional Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian households. The Russian sto ...

* The Russian oven or Russian stove is a unique type of

* The Russian oven or Russian stove is a unique type of oven

upA double oven

A ceramic oven

An oven is a tool which is used to expose materials to a hot environment. Ovens contain a hollow chamber and provide a means of heating the chamber in a controlled way. In use since antiquity, they have been use ...

/ furnace that first appeared in the early 15th century. The Russian oven is usually placed in the centre of the izba

An izba ( rus, изба́, p=ɪzˈba, a=Ru-изба.ogg) is a traditional Slavic countryside dwelling. Often a log house, it forms the living quarters of a conventional Russian farmstead. It is generally built close to the road and inside a ya ...

, a traditional Russian dwelling, and plays an immense role in the traditional Russian culture

Russian culture (russian: Культура России, Kul'tura Rossii) has been formed by the nation's history, its geographical location and its vast expanse, religious and social traditions, and Western influence. Russian writers and ph ...

and way of life. It is used both for cooking and domestic heating and is designed to retain heat for long periods of time. This is achieved by channeling the smoke and hot air produced by combustion through a complex labyrinth of passages, warming the bricks from which the oven is constructed. In winter people may sleep on top of the oven to keep warm. As well as warming and cooking, the Russian oven can be used for washing. A grown man can easily fit inside, and during the Great Patriotic War

The Eastern Front of World War II was a theatre of conflict between the European Axis powers against the Soviet Union (USSR), Poland and other Allies, which encompassed Central Europe, Eastern Europe, Northeast Europe (Baltics), an ...

some people escaped the Nazis by hiding in ovens. Porridge or pancakes prepared in such an oven may differ in taste from the same meal prepared on a modern stove or range. The process of cooking in a traditional Russian oven can be called "languor" - holding dishes for a long period of time at a steady temperature. Foods that are believed to acquire a distinctive character from being prepared in a Russian oven include baked milk

Baked milk (russian: топлёное молоко, ua, пряжене молоко, be, адтопленае малако) is a variety of boiled milk that has been particularly popular in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. It is made by simmering m ...

, pearl barley

Pearl barley, or pearled barley, is barley that has been processed to remove its fibrous outer hull and polished to remove some or all of the bran layer.

It is the most common form of barley for human consumption because it cooks faster and i ...

, mushroom

A mushroom or toadstool is the fleshy, spore-bearing fruiting body of a fungus, typically produced above ground, on soil, or on its food source. ''Toadstool'' generally denotes one poisonous to humans.

The standard for the name "mushroom" is ...

s cooked in sour cream

Sour cream (in North American English, Australian English and New Zealand English) or soured cream (British English) is a dairy product obtained by fermenting regular cream with certain kinds of lactic acid bacteria. The bacterial cultu ...

, or even a simple potato.

Rassolnik

* Rassolnik is a Russian soup made from pickled cucumber

A pickled cucumber (commonly known as a pickle in the United States and Canada and a gherkin in Britain, Ireland, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand) is a usually small or miniature cucumber that has been pickled in a brine, vinegar ...

s, pearl barley

Pearl barley, or pearled barley, is barley that has been processed to remove its fibrous outer hull and polished to remove some or all of the bran layer.

It is the most common form of barley for human consumption because it cooks faster and i ...

and pork or beef kidney

The kidneys are two reddish-brown bean-shaped organs found in vertebrates. They are located on the left and right in the retroperitoneal space, and in adult humans are about in length. They receive blood from the paired renal arteries; blo ...

s, though a vegetarian version also exists. The dish is known from the 15th century, when it was initially called ''kalya''. The key part of rassolnik is ''rassol